Pattern Formation in Predator-Prey Model with Delay and Cross Diffusion

Abstract

We consider the effect of time delay and cross diffusion on the dynamics of a modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey model incorporating a prey refuge. Based on the stability analysis, we demonstrate that delayed feedback may generate Hopf and Turing instability under some conditions, resulting in spatial patterns. One of the most interesting findings is that the model exhibits complex pattern replication: the model dynamics exhibits a delay and diffusion controlled formation growth not only to spots, stripes, and holes, but also to spiral pattern self-replication. The results indicate that time delay and cross diffusion play important roles in pattern formation.

1. Introduction

The spatial component of ecological interaction has been identified as an important factor in how ecological communities are shaped. Understanding the role of space is challenging both theoretics and empirism [1]. Empirical evidence suggests that the spatial scale and structure of environment can influence population interactions [2]. And pattern formation in nonlinear complex systems is one of the central problems of the natural, social, and technological sciences [3–12]. The classical approach to the origin of spatial structures was developed by Turing [13]. Understanding of patterns and mechanisms of species spatial dispersal is an issue of significant current interest in conservation biology and ecology. It arises from many ecological applications; particularly, it plays a major role in connection to biological invasion and disease spreading [14, 15].

Furthermore, in nature, there is a tendency that the preys would keep away from predators and the escape velocity of the preys may be taken as proportional to the dispersive velocity of the predators [45–49]. In the same manner, there is a tendency that the predators would get closer to the preys and the chase velocity of predators may be considered to be proportional to the dispersive velocity of the preys. Keeping these in view, cross-diffusion arises, which was proposed first by Kerner [50] and first applied in competitive population system by Shigesada et al. [51]. And there comes a question: how does cross-diffusion affect pattern formation in a delayed Leslie-Gower predator-prey model incorporating a prey refuge?

- (i)

The prey u and predator v are usually measured in mg of dry weight per liter [mg·dw/l].

- (ii)

Time t and time delay τ are measured in days [d].

- (iii)

The length of x, y ∈ (0, L) is measured in meter [m].

- (iv)

r is the growth rate of prey u and d is the growth rate of predator v, measured in [d−1].

- (v)

c is the maximum value of the per capita reduction of v due to u, which is not available in abundance and is measured in [d−1].

- (vi)

a describes the strength of competition among individuals of species u and is measured in [(mg · dw/l) −1d−1].

- (vii)

b describes the extent to which environment provides protection to prey u and predator v and is usually measured in mg of dry weight per liter [mg·dw/l].

- (viii)

dij > 0 (i, j = 1,2) are the diffusion coefficients corresponding to the prey and predator, respectively, and are measured in [m2d−1].

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we mainly present the Hopf and Turing bifurcation analysis. In Section 3, we perform a series of numerical simulation to show evolution process of prey u. And in the last section, we give some concluding remarks.

2. Bifurcation Analysis

It is easy to obtain that model (11) has three boundary equilibria E1 = (0,0), E2 = ((a/r), 0), and E3 = (0, (bd/r)) and a unique positive equilibrium E* = (u*, v*) = (((dm − d + cr)/ac), (((cab + (dm − d + cr)(1 − m))d)/ac2)).

Remark 1. In the case without time delay and cross-diffusion, that is, τ = 0 and d12 = d21 = 0, model (11) becomes (2). It is easy to see that E1, E2, E3, and E* are also equilibria of model (2). The stabilities of these equilibria of model (2) can be seen in [21].

In the following, we are mainly concerned with the properties of Hopf and Turing bifurcations for model (11).

For each j (j = 0,1, 2, …), Xj is invariant under the operator , and λ is an eigenvalue of D∇2 + LE on Xj if and only if λ is an eigenvalue of the matrix for some j ≥ 0.

2.1. Hopf Bifurcation

- (i)

ω2(τ) ≠ 0 for all τ ∈ I;

- (ii)

trace (Mj) < 0 and det (Mj) > 0 with uniformly for j ≥ 1 and τ ∈ I;

- (iii)

.

Thus, we have the following theorem.

Theorem 2. If , then model (11) undergoes a Hopf bifurcation that occurs around the positive equilibrium E* at τ = τc.

2.2. Turing Instability

In this subsection, we will state the Turing instability for the positive equilibrium E* of model (11).

Mathematically speaking, the positive equilibrium E* is Turing instability, which was emphasized by Turing in his pioneering work in 1952 [13], which means that it is asymptotically stable in the absence of diffusion in model (11) but unstable with respect to solutions in model (11). Hence, Turing instability occurs when either the condition trace (Mj) < 0 or the condition det (Mj) > 0 is violated.

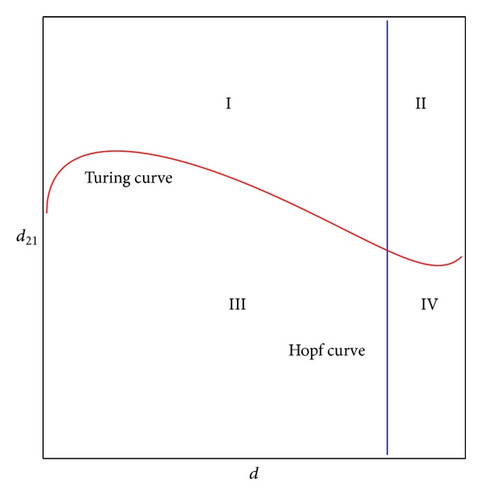

In Figure 1, we show the bifurcation diagram for model (11). The Turing instability curve and Hopf bifurcation curve separate the d − d21 parameter space into four domains. The domain on the left of the Hopf bifurcation curve is stable; the domain above Turing bifurcation curve is unstable. Hence, among these domains, only the domain I satisfies conditions of Theorem 3, and we call domain I as Turing space, where the Turing instability occurs and the Turing patterns may be undergone. Domain IV gives birth to spiral patterns.

3. Pattern Formation via Numerical Simulations

3.1. Turing Pattern Formation in Domain I

In this subsection, we first consider the pattern formation when parameters are located in domain I of Figure 1, which is pure Turing unstable domain.

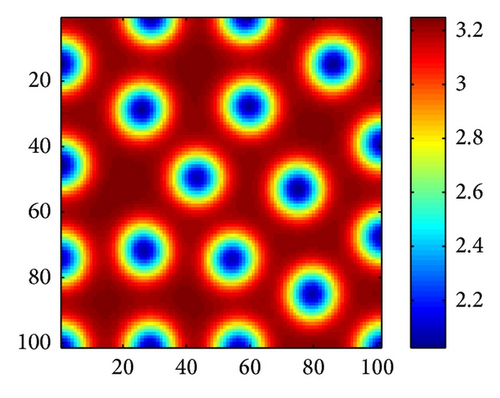

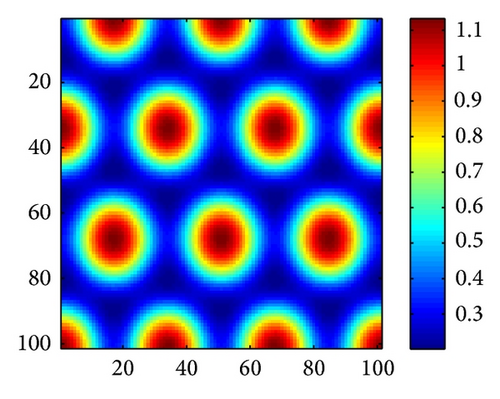

In the numerical simulations, different types of dynamics are observed, and it is found that the distributions of predator and prey are always of the same type. Consequently, we can restrict our analysis of pattern formation to one distribution. In the following, we show the distribution of prey u.

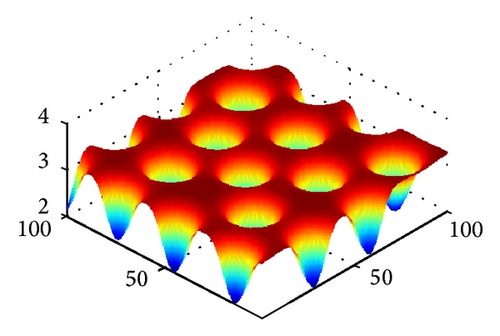

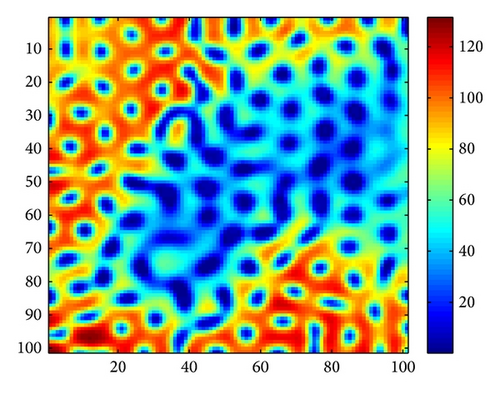

In Figure 2, we show three typical Turing patterns and their three-dimension pattern for model (4) at t = 2000. In the case of (d, d21, d22) = (0.08,0.89,0.37), the equilibrium is (u*, v*) = (2.8697,0.5203) and the holes patterns are isolated zones with low prey density (cf. Figure 2(a)). When increasing d to 0.4, (d, d21, d22) = (0.47,0.89,0.37), (u*, v*) = (0.9877,1.2218), the stripes patterns appear. While with (d, d21, d22) = (0.61,0.39,0.75), (u*, v*) = (0.3122,0.7306), spots patterns are isolated zones with high prey density (cf. Figure 2(c)). And Figures 2(d)-2(e) are three-dimension patterns corresponding to Figures 2(a)–2(c).

On the other hand, it is easy to check that holes, stripes, and spots also appear in model (4) without time delay for τ = 0 and other the parameters are taken the same way as in Figures 2(a)–2(c), respectively. However, in parameters of Figure 2, trace (Mj) < 0 and det (Mj) > 0 for all j ≥ 0 if the cross-diffusion coefficients d12 = 0 and d21 = 0. That is to say, model (4) is stable in absence of cross-diffusion, and this instability is induced by cross-diffusion.

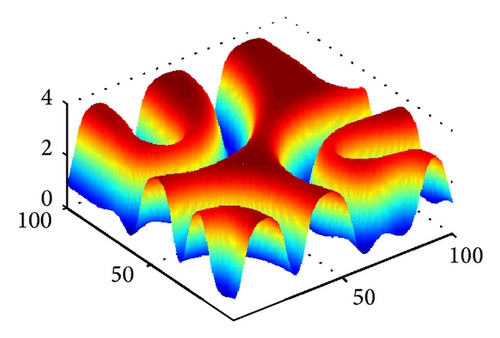

3.2. Chaotic Pattern Formation Domain II

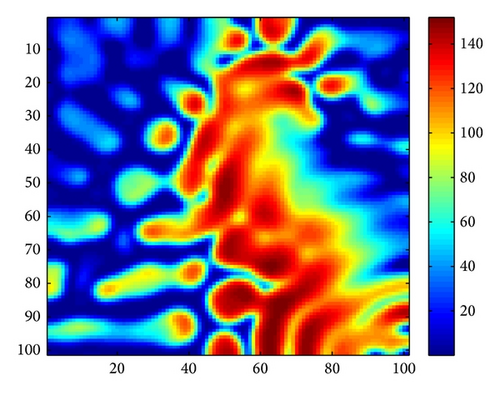

In this subsection, we will focus on the pattern formation when parameters are located in domain II of Figure 1, the domain of pure Hopf-Turing instability.

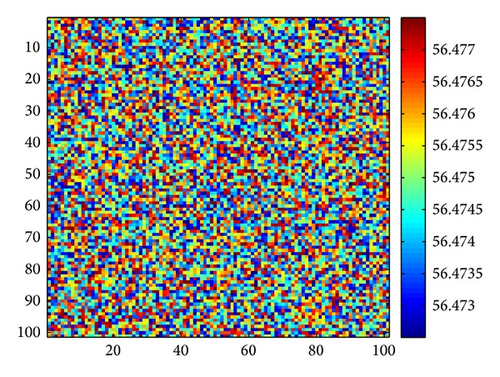

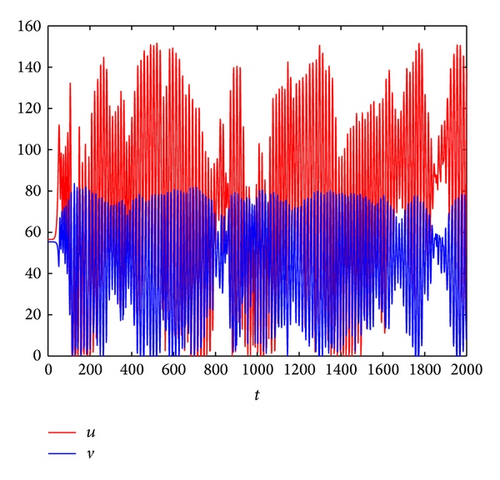

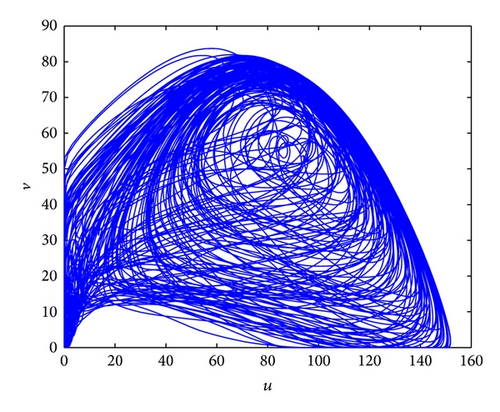

Figure 3 shows the evolution process of the spatial pattern of u at time t = 0,100,1000,2000 with parameter set (25) and a = 0.1, b = 0.71, r = 1.54, d = 0.47, d11 = 0.2, d21 = 0.44, d22 = 0.88, and τ = 0.46. The pattern takes a long time to settle down; starting with a homogeneous state E* = (56.4750,55.3357) (cf. Figure 3(a)), the random initial distribution leads to the formation of a strongly irregular transient pattern in the domain. After the irregular pattern form (cf. Figure 3(b)), it grows slightly and “jumps” alternately for a certain time, and finally the chaos patterns prevail over the whole domain (cf. Figures 3(c)-3(d)), which is time-dependent. For the sake of learning the spatiotemporal dynamics of model (4) further, we illustrate the time-series plots and phase portraits in Figures 3(e)-3(f). From the time-series plots in Figure 3(e), one can see that u and v strongly oscillates over time t. And in Figure 3(f), there exhibits a “local” phase plane of the system invaded by the irregular spatiotemporal oscillations; the trajectory now fills nearly the whole domain inside the quasi-limit cycle. This regime of the system dynamics corresponds to spatiotemporal chaos. And the spatial symmetry of model (4) is broken, and the patterns are oscillatory in space.

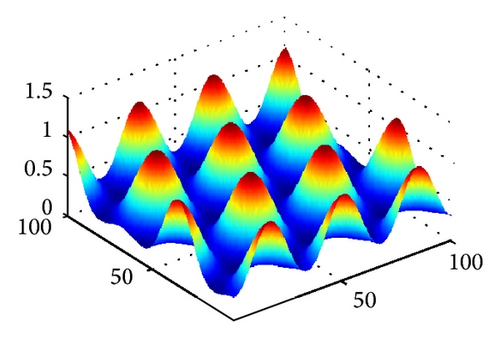

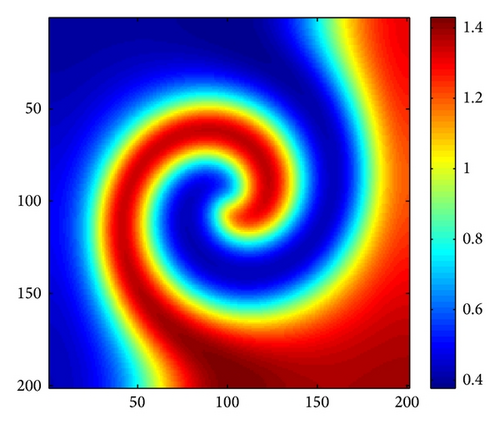

3.3. Spiral Wave Pattern Formation Domain IV

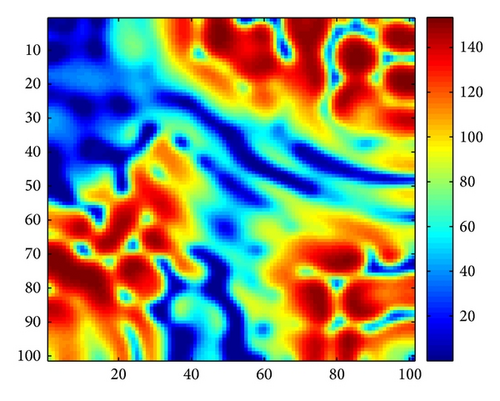

In this subsection, we will focus on the pattern formation when parameters are located in domain IV of Figure 1, the domain of pure Hopf instability.

In order to make any influence of the corners of the domain more visible, and thanks to the insightful work of Medvinsky et al. [4] and Upadhyay et al. [54], we have studied the spiral wave pattern for the following initial condition (27). In this case, we employ Δx = Δy = 1 and the system size is 200 × 200.

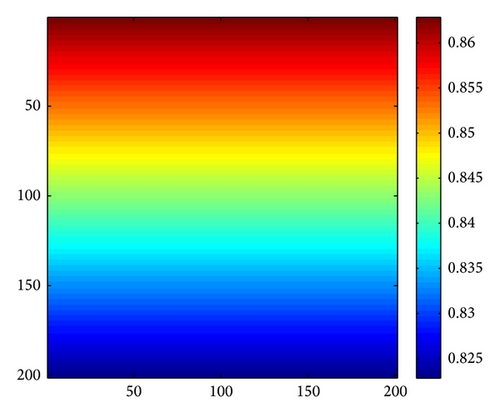

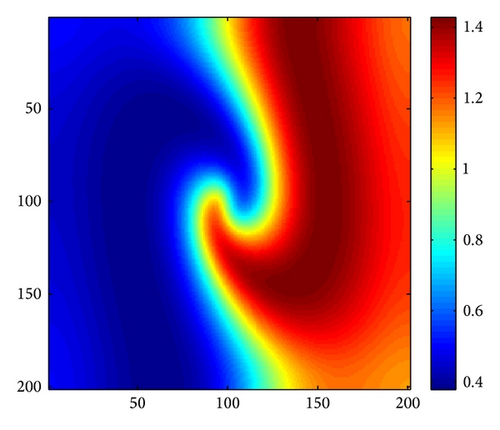

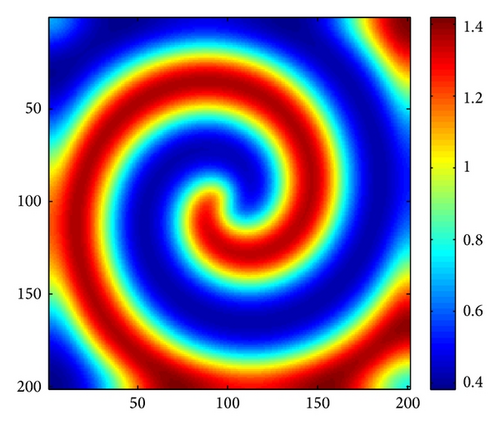

Figure 4 shows the evolution process of the spatial pattern of prey u at t = 0,500,1500,3000 with (d, d21, d22) = (0.5,0.15,0.37); the other parameters are fixed as in (25). Figure 4(a) shows that, for the model (4) with initial conditions (27), the formation of the irregular patchy structure can be preceded by the evolution of a regular spiral spatial pattern. Note that the appearance of the spirals is not induced by the initial conditions. The center of each spiral is situated in a critical point (xcr, ycr) = (100,100), where u(xcr, ycr) = u*, v(xcr, ycr) = v*. After the spirals form (Figure 4(b)), they grow slightly for a certain time and their spatial structure becomes more distinct (Figures 4(c) and 4(d)). Obviously, spiral pattern arises from Hopf instability.

4. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we analyze the spatiotemporal dynamics of a spatial Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with time delay and diffusion under the zero-flux boundary conditions. The value of this study is twofold. First, it gives the conditions of Hopf and Turing instability induced by the effects of time delay and cross-diffusion. Second, it gives three domains for three kinds of patterns of model (4) and finds that time delay and cross-diffusion may induce Turing instability, resulting in stationary Turing patterns, Hopf instability, resulting in spiral wave patterns, and Turing-Hopf instability, resulting in chaotic wave patterns.

If τ is small enough, it is worthy to note that, for the delayed model (4), two typical patterns are similar to those in our previous work [43] (a special case of model (4) with self diffusion): pure Turing instability gives birth to the holes, stripes, and spots patterns (cf. Figure 2) and pure Hopf instability to spiral wave pattern (cf. Figure 4). But this is not forever. In the present paper, we find that the delayed reaction-diffusion model (4) exhibits more complex pattern formation, for there exists the third pattern, chaotic wave pattern, which is induced by Turing-Hopf instability. The complexity of the pattern formation is induced by the cross-diffusion effect.

The results of the formation of these patterns may indicate the vital role of phase transience regimes in the spatiotemporal organization of the prey and predator in the real world situation. It is also important to distinguish between “intrinsic” patterns, that is, Turing patterns arising due to predation, and “forced” patterns induced by the heterogeneity of the environment, that is, spiral wave pattern. Because of the environmental heterogeneity, the dispersion of varying quantities and typical times and lengths can be essentially different in different cases and thus can induce different spatial patterns.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referee for the very helpful suggestions and comments which led to the improvement of our original paper. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (61373005), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LY12A01014), and the Fund Project of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Y201223449).