On a New Method for Computing the Numerical Solution of Systems of Nonlinear Equations

Abstract

We consider a system of nonlinear equations F(x) = 0. A new iterative method for solving this problem numerically is suggested. The analytical discussions of the method are provided to reveal its sixth order of convergence. A discussion on the efficiency index of the contribution with comparison to the other iterative methods is also given. Finally, numerical tests illustrate the theoretical aspects using the programming package Mathematica.

1. Preliminaries

There are many approaches to solve the system (1.1). One of the best iterative methods to challenge this problem is Newton’s method. This method starts with an initial guess x(0) and after k updates and by considering a stopping criterion satisfies (1.1).

A benefit of Newton’s method is that the obtained sequence converges quadratically if the initial estimate is close to the exact solution. However, there are some downsides of the method. One is the selection of the initial guess. A good initial guess can lead to convergence in a couple of steps. To improve the initial guess, several ideas can be found in the literature; see, for example, [4–6].

In what follows, we assume that F(x) is a smooth function of x in the open convex set D⊆ℝn. There are plenty of other solvers to tackle the problem (1.1); see, for example, [7–10]. Among such methods, the third-order iterative methods like the Halley and Chebyshev methods [11] are considered less practically from a computational point of view because they need to compute the expensive second-order Frechet derivatives in contrast to the quadratically convergent method (1.2), in which the first-order Frechet derivative needs to be calculated.

As could be seen, (1.5) and (1.6) include the evaluations F(x(k)), F′(x(k)), and F′(y(k)).

The primary goal of the present paper is to achieve both high order of convergence and low computational load in order to solve (1.1) with a special attention to the matter of efficiency index. Hence, we propose a new iterative method with sixth-order convergence to find both real and complex solutions. The new proposed method needs not the evaluation of the second-order Frechet derivative.

The rest of this paper is prepared as follows. In Section 2, the construction of the novel scheme is offered. Section 3 includes its analysis of convergence behavior, and it shows the suggested method has sixth order. Section 4 contains a discussion on the efficiency of the iterative method. This is followed by Section 5 where some numerical tests will be furnished to illustrate the accuracy and efficiency of the method. Section 6 ends the paper, where a conclusion of the study is given.

2. The Proposed Method

Now the implementation of (2.2) depends on the involved linear algebra problems. For large-scale problems, one may apply the GMRES iterative solver which is well known for its efficiency for large sparse linear systems.

Remark 2.1. The interesting point in (2.2) is that three linear systems should be solved per computing step, but all have the same coefficient matrix. Hence, one LU factorization per full cycle is needed, which reduces the computational load of the method when implementing.

We are about to prove the convergence behavior of the proposed method (2.2) using n-dimensional Taylor expansion. This is illustrated in the next section. An important remark on the error equation in this case comes next.

Remark 2.2. In the next section, e(k) = x(k) − x* is the error in the kth iteration and is the error equation, where L is a p-linear function, that is, L ∈ ℒ(ℝn, ℝn, …, ℝn) and p is the order of convergence. Observe that .

3. Convergence Analysis

Let us assess the analytical convergence rate of method (2.2) in what follows.

Theorem 3.1. Let F : D⊆ℝn → ℝn be sufficiently Frechet differentiable at each point of an open convex neighborhood D of x* ∈ ℝn, that is a solution of the system F(x) = 0. Let one suppose that F′(x) is continuous and nonsingular in x*. Then, the sequence {x(k)} k≥0 obtained using the iterative method (2.2) converges to x* with convergence rate six, and the error equation reads

Proof. Let F : D⊆ℝn → ℝn be sufficiently Frechet differentiable in D. By using the notation introduced in [14], the qth derivative of F at u ∈ ℝn, q ≥ 1, is the q-linear function F(q)(u) : ℝn × ⋯×ℝn → ℝn such that F(q)(u)(v1, …, vq) ∈ ℝn. It is well known that, for x* + h ∈ ℝn lying in a neighborhood of a solution x* of the nonlinear system F(x) = 0, Taylor expansion can be applied and we have

4. Concerning the Efficiency Index

Now we assess the efficiency index of the new iterative method in contrast to the existing methods for systems of nonlinear equations. In the iterative method (2.2), three linear systems based on LU decompositions are needed to obtain the sixth order of convergence. The point is that for applying to large-scale problems one may solve the linear systems by iterative solvers and the number of linear systems should be in harmony with the convergence rate. For example, the method of Sharma et al. (1.5) requires three different linear systems for large sparse nonlinear systems, that is, the same with the new method (2.2), but its convergence rate is only 4, which clearly shows that method (2.2) is better than (1.5).

Now let us invite the number of functional evaluations to obtain the classical efficiency index for different methods. The iterative method (2.2) has the following computational cost (without the index k): n evaluations of scalar functions for F(x), n evaluations of scalar functions F(z), n2 evaluations of scalar functions for the Jacobian F′(x), and n2 evaluations of scalar functions for the Jacobian F′(y).

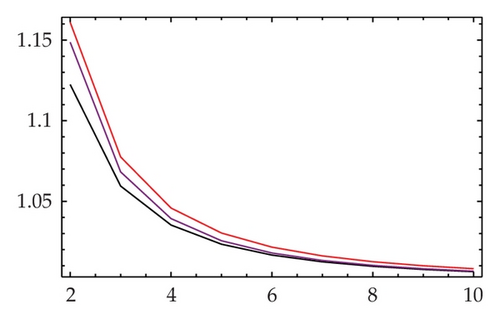

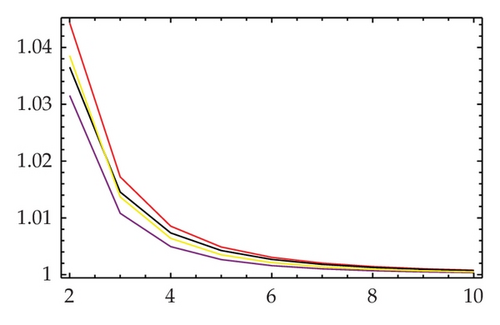

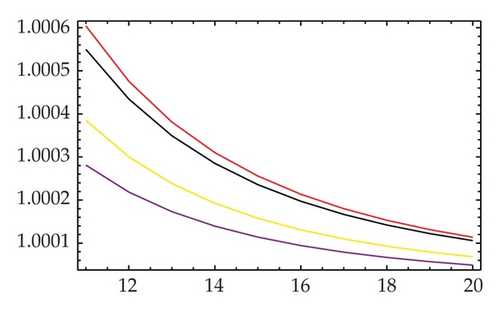

We now provide the comparison of the classical efficiency indices for methods (1.2), (1.5), and (1.6) alongside the new proposed method (2.2). The plot of the index of efficiencies according to the definition of the efficiency index of an iterative method, which is given by E = p1/C, where p is the order of convergence and C stands for the total computational cost per iteration in terms of the number of functional evaluations, is given in Figure 1. A comparison over the number of functional evaluations of some iterative methods is also illustrated in Table 1. Note that both (1.5) and (1.6) in this way have the same classical efficiency index.

| Iterative methods | (1.2) | (1.5) | (1.6) | (2.2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of steps | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Rate of convergence | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Number of functional evaluations | n + n2 | n + 2n2 | n + 2n2 | 2n + 2n2 |

| The classical efficiency index | ||||

| Number of LU factorizations | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

|

2n3/3 | 4n3/3 | 4n3/3 | 2n3/3 |

| Cost of linear systems (based on flops) | (2n3/3) + 2n2 | (10n3/3) + 2n2 | (7n3/3) + 2n2 | (5n3/3) + 4n2 |

| Flops-like efficiency index |

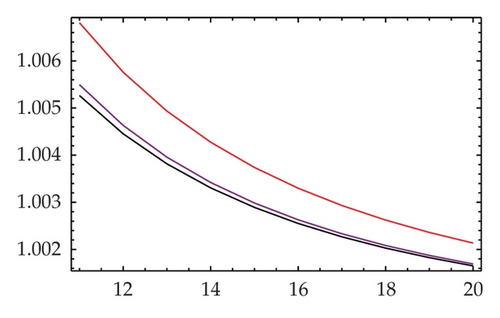

In Figures 1 and 2, the colors yellow, black, purple, and red stand for methods (1.6), (1.2), (1.5), and (2.2), respectively. It is clearly obvious that the new method (2.2) for any n ≥ 2 has dominance with respect to the traditional efficiency indices on the other well-known and recent methods.

As was positively pointed out by the second referee, taking into account only the number of evaluations for scalar functions cannot be the effecting factor for evaluating the efficiency of nonlinear solvers. The number of scalar products, matrix products, decomposition LU of the first derivative, and the resolution of the triangular linear systems are of great importance in assessing the real efficiency of such schemes. Some extensive discussions on this matter can be found in the recent literature [15, 16].

To achieve this goal, we in what follows consider a different way. Let us count the number of matrix quotients, products, summations, and subtractions along with the cost of solving two triangular systems, that is, based on flops (the real cost of solving systems of linear equations). In this case, we remark that the flops for obtaining the LU factorization are 2n3/3, and to solve two triangular system, the flops would be 2n2. Note that if the right-hand side is a matrix, the cost (flops) of the two triangular systems is 2n3, or roughly n3 as considered in this paper. Table 1 also reveals the comparisons of flops and the flops-like efficiency index. Note that to the best of the authors’ knowledge, such an index has not been given in any other work. Results of this are reported in Table 1 and Figure 2 as well. It is observed that the new scheme again competes all the recent or well-known iterations when comparing the computational efficiency indices.

5. Numerical Testing

We employ here the second-order method of Newton (1.2), the fourth-order scheme of Sharma et al. (1.5), the fourth-order scheme of Soleymani (1.6), and the proposed sixth-order iterative method (2.2) to compare the numerical results obtained from these methods in solving test nonlinear systems. In this section, the residual norm along with the number of iterations in Mathematica 8 [17] is reported in Tables 2-3. The computer specifications are Microsoft Windows XP Intel(R), Pentium(R) 4 CPU, 3.20 GHz with 4 GB of RAM. In numerical comparisons, we have chosen the floating point arithmetic to be 256 using the command SetAccuarcy[expr, 256] in the written codes. The stopping criterion (for the first two examples) is the residual norm of the multivariate function to be less than 1 · E − 150, that is, | | F(x(k))|| ≤ 10−150. Note that for some iterative methods if their residual norms at the specified iteration exceed the bound of 10−200, we will consider that such an approximation is the exact solution and denoted the residual norm by 0 in some cells of the tables. We consider the test problems as follows.

Example 5.1. As the first test, we take into account the following hard system of 15 nonlinear equations with 15 unknowns having a complex solution to reveal the capability of the new scheme in finding (n-dimensional) complex zeros:

In this test problem, the approximate solution up to 2 decimal places can be constructed based on a line search method for obtaining robust initial value as follows: x* ≈ (1.98 + 0.98I, 3.40 − 0.76I,1.81 − 0.63I, 3.49 + 0.87I, 6.55 − 0.90I,1.33 − 1.01I, 79.10 + 48.26I,3.08 + 0.83I, 5.32 − 1.52I, 0.02 + 0.01I, 0.00 + 0.1I, 13.80 − 26.64I,1.14 + 2.17I, −2.69 − 6.94I, −3.30 + 0.00I) T. The results for this test problem are given in Table 2.

Results in Table 2 show that the new scheme can be considered for complex solutions of hard nonlinear systems as well. In this test, we have used the LU decomposition, when dealing with linear systems.

Example 5.2. In order to tackle with large-scale nonlinear systems, we have included this example in this work:

We report the numerical results for solving Example 5.2 in Table 3 based on the initial value x0 = Table [2., {i, 1,99}]. The case for 99 × 99 is considered. In Table 3, the new scheme is good in terms of the obtained residual norm in a few number of iterations.

Throughout the paper, the computational time has been reported by the command AbsoluteTiming[]. The mean of 5 implementations is listed as the time. In the following example, we consider the application of such nonlinear solvers when challenging hard nonlinear PDEs or nonlinear integral equations, some of such applications have also been given in [18–20].

Example 5.3. Consider the following nonlinear system of Volterra integral equations:

Numerical results for this example are reported in Table 4. We again used 256-digit floating point in our calculations but the stopping criterion is the residual norm to be accurate for seven decimal places at least, that is to say, | | F(x(k))|| ≤ 10−7. The starting values are chosen as (−10, …, −10) T. In this case, we only report the time of solving the system (5.4) by the iterative methods and do not include the computational time of spectral method to first discretize (5.4).

6. Conclusions

In this paper, an efficient iterative method for finding the real and complex solutions of nonlinear systems has been presented. We have supported the proposed iteration by a mathematical proof through the n-dimensional Taylor expansion. This let us analytically find the sixth order of convergence. Per computing step, the method is free from second-order Frechet derivative.

A complete discussion on the efficiency index of the new scheme was given. Nevertheless, the efficiency index is not the only aspect to take into account: the number of operations per iteration is also important; hence, we have given the comparisons of efficiencies based on the flops and functional evaluations. Some different numerical tests have been used to compare the consistency and stability of the proposed iteration in contrast to the existing methods. The numerical results obtained in Section 5 reverified the theoretical aspects of the paper. In fact, numerical tests have been performed, which not only illustrate the method practically but also serve to check the validity of theoretical results we had derived.

Future studies could focus on two aspects, one to extend the order of convergence alongside the computational efficiency and second to present some hybrid algorithm based on convergence guaranteed methods (at the beginning of the iterations) to ensure being in the trust region to apply the high-order methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the reviewers for offering some helpful comments on an earlier version of this work. The work of the third author is financially supported through a Grant by the University of Venda, South Africa.