Study of Tracer Diffusion Mechanism in Amorphous Metal

Abstract

The statistical relaxation (SR) simulation has been conducted to study the behavior of simplexes and bubbles (BB) in amorphous Co metal containing 2 × 105 atoms. The simulation reveals that the fraction of 4-simplex increases and n-simplex (n > 4) decreases depending upon relaxation degree. The simulation found that a large number of BB vary upon relaxation degree, which could play a role of diffusion vehicle for Co atoms in amorphous matrix. The idea of the diffusion mechanism in amorphous metal is described as follows: the elemental atomic movement includes a jump of neighboring atom into the BB and then a collective displacement of a large number of atoms around BB.

1. Introduction

The diffusion behavior in amorphous metals (AMs) has been intensively studied by both experiment and simulation for long times [1–8]. It is found that there are many specific properties of diffusion in AM compared to crystal matters. For example, the tracer diffusivity in a well-relaxed sample is much slower than the one in an as-quenched sample [9, 10]. This relaxation effect is interpreted by the reduction of vacancies in supersaturation until the relaxation is over. In the well-relaxed sample, conversely, the tracer atoms diffuse via collective movement of a group of neighboring atoms. The experimental studies in [11–13] on isotope effect, pressure dependence, and irradiation-enhanced diffusivity are sometimes in contradiction with the diffusion described above. Furthermore, there is not a clear definition of vacancy. Computer simulation, on the other hand, reveals unstableness of vacancies in amorphous matrix. Several works found a continuous spectrum of spherical voids in amorphous matter, but their size is less than atomic radius [14–16]. The free volume and two-level state theories are also employed to interpret the diffusion behavior of amorphous matter, but they cannot properly describe the diffusivity in some amorphous matters such as Ti60N40 and Fe40Ni40B20 which show the cooperative activated movement more like diffusivity in solid state than in liquid [2, 17–20]. In [21], Sietsma and Thijsse analyzed different types of holes in amorphous matters and found that the number of holes surrounded by ten or more atoms decreases strongly in a well-relaxed sample. Furthermore, they argue the importance of big holes for atomic diffusivity.

Our previous study shows that amorphous matters suffer from a number of spherical voids, the size of which is closed to atomic size. Because the concentration of those voids weakly depends on temperature, it is very sensitive to the relaxation degree. We call them “native vacancy,” which fully disappears until the amorphous matters transform into crystalline solid. However, the analysis of this study is based only on the geometrical consideration. Therefore, the account of potential barrier could provide more accurate elucidation of the voids for diffusion in amorphous matters. The aim of the present work is the study of simplexes and their role of them in diffusion in Co amorphous metals by using SR simulation method as a way to clarify diffusion mechanism in amorphous matters.

2. Calculation Method

Initial configuration is generated by randomly placing all atoms in a simulation box. Then, the sample is relaxed over several thousand steps until the system attains the equilibrium, for example, the energy of system fluctuates around a constant value and the pressure is equal to zero.The model A is constructed by relaxing with dr = 0.4 Å over 200 SR steps and then is treated with dr = 0.01 Å by 106 SR steps. To investigate the relaxation effect, two additional samples (samples B and C) are prepared with the same density as sample A, but their potential energy is lower (more stable state). Note that the lower the energy of the system the bigger its relaxation degree. More stable samples B and C can be constructed many times with relaxing the model A that has dr = 0.4 Å, which likes the shaking of atomic structure. Then, they are again relaxed with dr = 0.01 Å until the system reaches a new equilibrium.

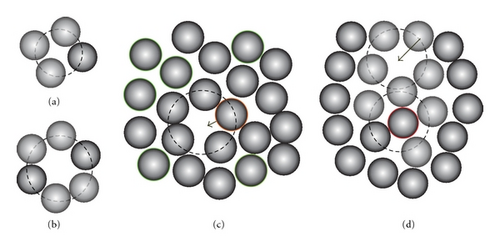

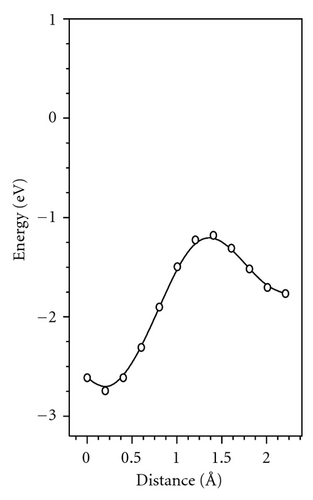

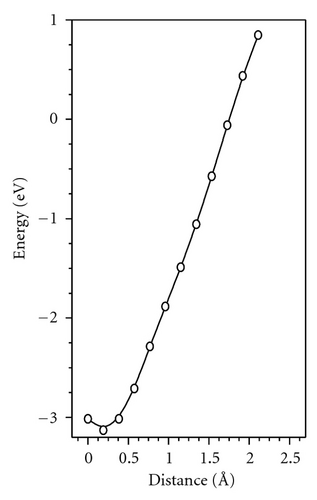

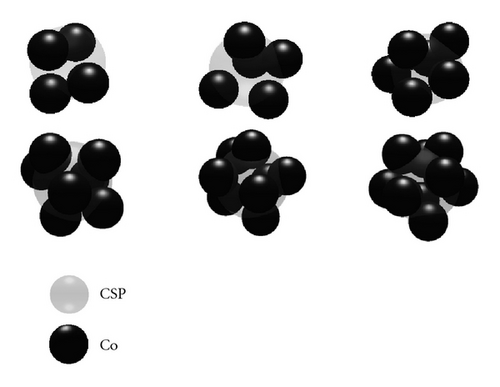

Four neighboring atoms form a tetrahedron and have a circumsphere (CSP) whose surface passes through the vertices of this tetrahedron. Consider only such tetrahedron with CSP that does not contain any atom inside. For example, those atoms are the nearest neighboring. Let RCSP and n be the radius of CSP and the number of atoms on the surface of CSP, respectively. The atom on surface of CSP is determined as one that is located from the center of CSP at a distance in range of RCSP ± 0.1 Å. hereafter we call it n-simplex (see Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). If n and RCSP is large enough, then n atoms form an atomic cage like a bubble (BB), for example, a large group of atoms gathered around a large void. The BB is unstable and it may break up leading to diffusion. Therefore, it is interesting to clarify which one among n-simplexes is BB and how BB breaks up. Hence, the next calculation is performed as follows: first for every simplex, we test all n atoms to perform jump inside the CSP. Second, the atom selected to move is inserted inside CSP and the system is relaxed until it reaches equilibrium.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Sample

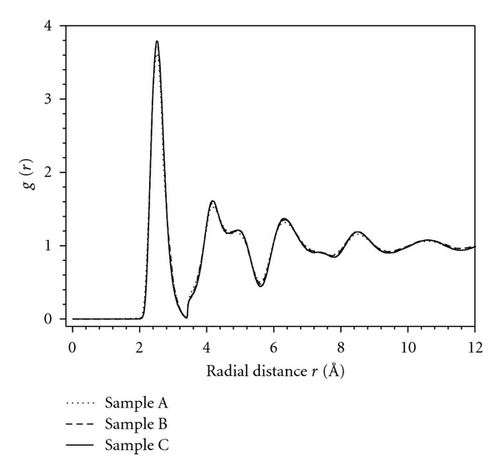

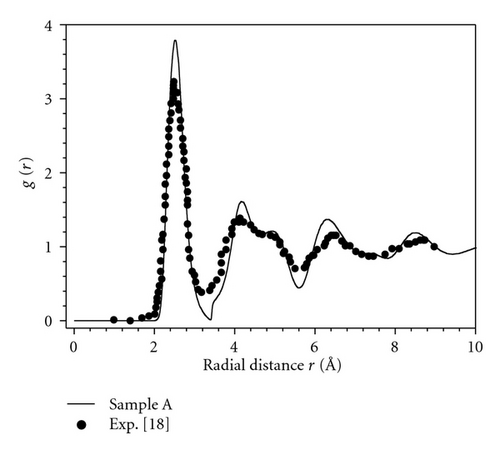

Figure 2 shows the radial distribution function (RDF) g(r) of the amorphous samples. As shown in Figure 2, although the energy per atom of the considered samples changes from −0.9336 to −0.9534 eV, the RDF g(r) for the considered samples is identical. This indicates the nonsensitivity of the function g(r) to the change in local microstructure of AMs. This result further indicates that the relaxation degree almost does not affect RDF, but it is reflected by the concentration of simplex. To test the validity of the constructed samples, we have compared our obtained RDF with the experimental data. As shown from Figure 3 the structural characteristics of our samples are in accordance with the experiment data [22]. In addition, the function g(r) has a splitting second peak, which is often thought to be related to the icosahedrons in amorphous systems [17, 18, 20]. The main characteristics of the samples are listed in Table 1. The comparison with experiment shows agreement in the position and height of the first peak of RDF, which indicates the reality of the constructed sample.

| Systems | r1 | r2/r1 | r3/r1 | r4/r1 | r5/r1 | g(r) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample A | 2.51 | 1.67 | 1.99 | 2.52 | 3.39 | 3.64 |

| Sample B | 2.52 | 1.67 | 1.99 | 2.51 | 3.38 | 3.75 |

| Sample C | 2.50 | 1.66 | 2.01 | 2.54 | 3.44 | 3.78 |

| aCo | 2.49 | 1.69 | 1.93 | 2.49 | 3.35 | 3.20 |

| bCo | — | 1.65 | 1.90 | 2.57 | 3.46 | — |

3.2. Simplex and Role of Simplex

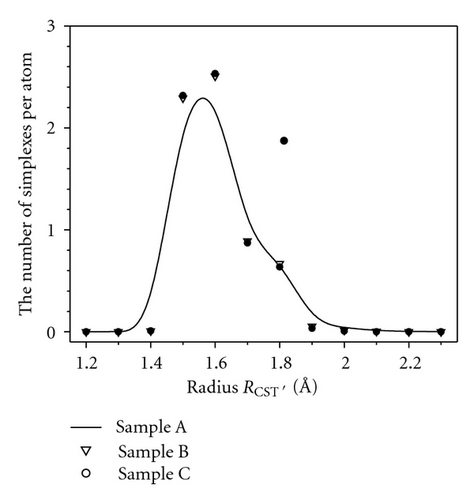

Table 2 presents the energy per atom and fraction of simplex found in the obtained samples. One can see that the energy per atom decreases from −0.9336 to −0.9534 eV, upon relaxation degree. The fraction of 4-simplex increases as the sample potential energy decreases, that is, the more stable state is, bigger the number of 4-simplexes is. For other kinds of simplex, we observe the opposite trend. Thus, it means that due to fast quenching from liquid the parking of atoms in AM is not efficient. Therefore, there is always an amount of structural defects like large void (free volume). The relaxation is accompanied by annihilation of those defects. As mentioned above, the bigger number n is, the bigger the size of simplex and void inside it is. Therefore, Table 2 specifies that the monotony decrease in the number of n-simplex with n > 4 from less relaxed (sample A) to well relaxed state (sample C) indicates the annihilation of structural defects in amorphous matrix. This result also can be seen in the radius distribution of simplex as in Figure 4. From Figure 4, one can see clearly the significant decrease in the number of large simplex (RCSP > 1.8 Å) in the sample A as compared to the sample C. We proposed that the large simplex (n = 6, 7, 8) is broken up into 4-simplex under the relaxation degree. So as the concentration of 4-simplex increases, the large simplex decreases.

| Systems | ε(eV) | 4 (×100) | 5 (×10−1) | 6 (×10−2) | ≥7 (×10−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample A | −0.9336 | 0.961 | 0. 374 | 0.173 | 0.02 |

| Sample B | −0.9462 | 0.963 | 0. 358 | 0.167 | 0.00 |

| Sample C | −0.9534 | 0.964 | 0.339 | 0.164 | 0.00 |

| Systems | nBB (×10−3) | D0 (m2/s) |

|---|---|---|

| Samples A | 8.39 | 9.3 × 10−6 |

| Samples B | 1.34 | 6.1 × 10−7 |

| Samples C | 0.31 | 1.1 × 10−7 |

| cCo89Zr11 | — | 8.0 × 10−7 |

| dCo79Nb14B7 | — | 3.3 × 10−6 |

Several experimental findings shows that (i) sudden temperature change during diffusion annealing results in instantaneous change of diffusion coefficient (DR) and (ii) The self-diffusion enthalpy H of transition metal for certain amorphous alloy seems to be the migration enthalpy, but not a sum of migration and formation enthalpy of diffusion vehicles as it is the case of self-diffusion in crystal [3]. These experimental observations are interpreted as a result of direct diffusion mechanism occurring in relaxed amorphous sample. Our simulation result shows possible diffusivity via the bubble. It is consistent with the experiment because the concentration of bubbles is independent of temperature, and they vary only with relaxation degree. So, the activation energy for diffusion via the bubble is equal to the migration energy (Em).

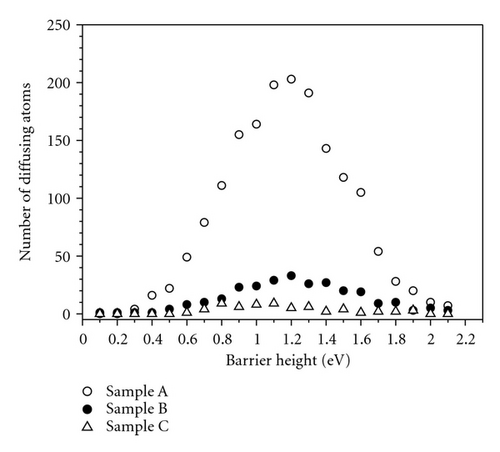

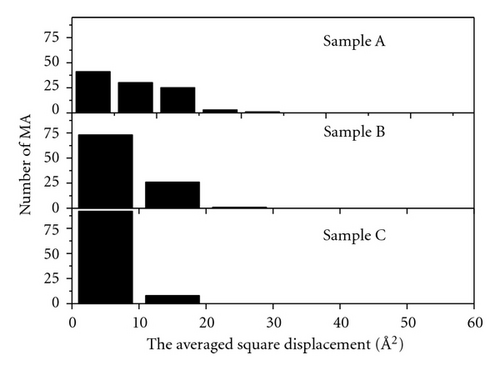

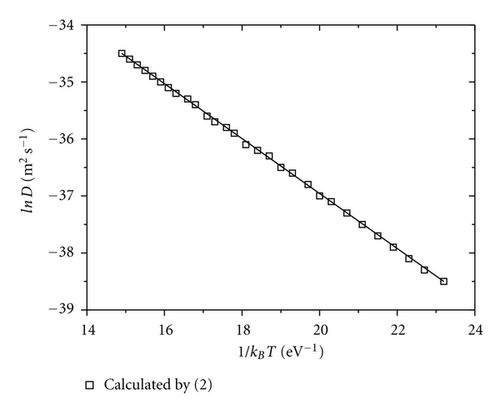

To estimate the parameter 〈d2〉 in (2), we replace DA into CSP and then relax the system until a new equilibrium is attained. This procedure for convenience is called the remove diffusion atom (RDA). The distribution of mean square displacements for 100 RDAs is displayed in Figure 8. For sample C, the parameter 〈d2〉 of most RDAs is less than 10 Å2 (92 atoms). Because the jump length of DA lies in the interval of 2.0–3.0 Å, the contribution of DA to 〈d2〉 will be essential and the RDA locates only in the small region nearby the bubble. In the case of sample A, we observe a very large value of 〈d2〉 (more than 10 Å2), which represents a collective movement of a large number of atoms. Obviously, the atomic movement is spread over a large volume inside the amorphous matrix as shown in Figure 1(d). Therefore, one may see two distinct diffusion mechanisms occurring in the as-quenched (sample A) and well-relaxed metastable states (sample C). The first one is like the hoping mechanism via bubble. The second one relates to the collective mechanism involving a large number of atoms in each elemental diffusion movement. Assume that f = 1, exp (Δsm/kB) ≈ 1, v0 = 1012 s−1, 〈d2〉 ≈ 10 Å2 for sample C and 100 Å2 for sample A. The diffusion coefficient of Co atom can be estimated on the base of (2). Although the barrier heights for different jumps vary from 0.5 to 1.9 eV, the DCo diffusion coefficient is found to obey the Arrehenius behavior as shown in Figure 9. According to (3), the pre-exponential factor is calculated as shown in Table 3. The calculation data is consistent with the experimental data for the amorphous samples [25, 26].

4. Conclusions

- (i)

The microstructure of the cobalt samples containing 2 × 105 atoms is in agreement with the experimental data. The fraction of 4-simplex increases and n-simplex (n > 4) decreases depending upon relaxation degree. The simulation reveals that a large number of bubbles vary with relaxation degree in AM.

- (ii)

A bubbles diffusion mechanism in AM is proposed for the elemental atomic movement, which includes a jump of neighboring atom into the bubbles and then collective displacement of a number of atoms. It may be seen two distinct diffusion mechanisms occurring in the as-quenched and well-relaxed samples. The decrease in pre-exponential factor upon relaxation is ascribed to the partial annihilation of bubbles. The obtained pre-exponential factor of Co atom is found to be in accordance with the experiment data.