Rotations in the Space of Split Octonions

Abstract

The geometrical application of split octonions is considered. The new representation of products of the basis units of split octonionic having David′s star shape (instead of the Fano triangle) is presented. It is shown that active and passive transformations of coordinates in octonionic “eight-space” are not equivalent. The group of passive transformations that leave invariant the pseudonorm of split octonions is SO(4, 4), while active rotations are done by the direct product of O(3, 4)-boosts and real noncompact form of the exceptional group G2. In classical limit, these transformations reduce to the standard Lorentz group.

1. Introduction

Nonassociative algebras may surely be called beautiful mathematical entities. However, they have never been systematically utilized in physics, only some attempts have been made toward this goal. Nevertheless, there are some intriguing hints that nonassociative algebras may play essential role in the ultimate theory, yet to be discovered.

Octonions are one example of a nonassociative algebra. It is known that they form the largest normed algebra after the algebras of real numbers, complex numbers, and quaternions [1–3]. Since their discovery in 1844/1845 by Graves and Cayley there have been various attempts to find appropriate uses for octonions in physics (see reviews [4–7]). One can point to the possible impact of octonions on: Color symmetry [8–11]; GUTs [12–15]; Representation of Clifford algebras [16–19]; Quantum mechanics [20–24]; Space-time symmetries [25, 26]; Field theory [27–29]; Formulations of wave equations [30–32]; Quantum Hall effect [33]; Kaluza-Klein program without extra dimensions [34–36]; Strings and M-theory [37–40]; and so forth.

In this paper we study rotations in the model, where geometry is described by the split octonions [41–43].

2. Octonionic Geometry

Let us review the main ideas behind the geometrical application of split octonions presented in our previous papers [41–43]. In our model some characteristics of physical world (such as dimension, causality, maximal velocities, and quantum behavior) can be naturally described by the properties of split octonions. Interesting feature of the geometrical interpretation of the split octonions is that their pseudonorms, in addition to some other terms, already contain the ordinary Minkowski metric. This property is equivalent to the existence of local Lorentz invariance in classical physics.

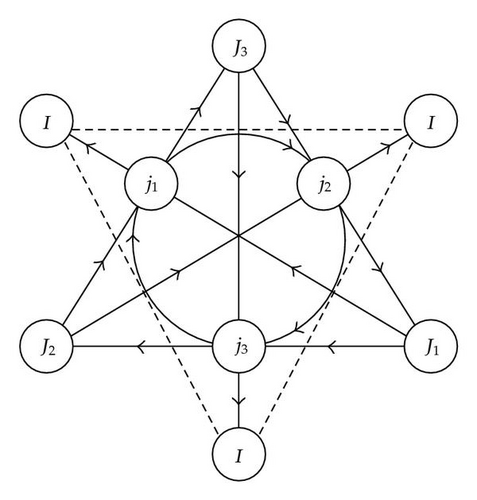

The multiplication table of octonionic units is most transparent in graphical form. To visualize the products of ordinary octonions the Fano triangle is used [1–3], where the seventh basic unit I is place at the center of the graph. In the algebra of split octonions we have less symmetry, and for a proper description of the products (2.3) the Fano graph should be modified by shifting I from the center of the Fano triangle. Also we will use three equivalent representations of I, (2.5), and, instead of the Fano triangle, we arrive at David′s star shaped duality plane for products of the split octonionic basis elements.

On this graph the product of two basis units is determined by following the oriented solid line connecting the corresponding nodes. Moving opposite to the orientation of the line contributes a minus sign to the result. Dashed lines just show that the corners of the triangle with I nodes are identified.

3. Rotations

To describe rotations in 8-dimensional octonionic space (2.1) with the interval (2.8) we need to define exponential maps for the basis units of split octonions.

In 8-dimensional octonionic “space-time’’ (2.1) there is no unique plane orthogonal to a given axis. Therefore for the operators (3.1) and (3.2) it is not sufficient to specify a single rotation axis and an angle of rotation. It can be shown that the left multiplication of the octonion s by one of the operators (3.1), (3.2) (e.g., ) yields four simultaneous rotations in four mutually orthogonal planes. For simplicity we consider only the left products since it is known that one side multiplications generate the whole symmetry group that leaves the octonionic norms invariant [46].

In contrast with uniform rotations giving by the operators jn we have limited rotations in the planes orthogonal to (1 − Jn) and (1 − I). However, we can still perform a decomposition similar to (3.4) of s using expressions of the exponential maps (3.2). But now, unlike on (3.5), the norms of the corresponding planes are not positively defined and, instead of the condition (3.7), we should require positiveness of the norms of each four planes. For example, the pseudoscalar-like basis unit I has three different representations (2.5), and it can provide the hyperbolic rotations (3.2) in the orthogonal planes (1 − I), (J1 − j1), (J2 − j2), and (J3 − j3). The expressions for the 2 norms (3.5) in this case are: , , , and .

Now let us consider active and passive transformations of coordinates in 8-dimensional space of signals (2.1). With a passive transformation we mean a change of the coordinates t, xn, λn, and ω, as opposed to an active transformation which changes the basis 1, Jn, jn, and I.

Now let us consider active coordinate transformations, or transformations of basis units 1, Jn, jn, and I. For them, because of nonassociativity, the results of two different rotations (3.1) and (3.2) are not unique. This means that not all active octonionic transformations (3.1) and (3.2) form a group and can be considered as a real rotation. Thus in the octonionic space (2.1) not to the all passive SO(4,4)-transformations we can make corresponding active ones, only the transformations that have a realization as associative multiplications should be considered. It is known that associative transformations can be done by the combined rotations of special form in two octonionic planes that form a subgroup of SO(4,4), known as the automorphism group of split octonions (the real noncompact form of Cartan′s exceptional Lie group G2). Some general results on and its subgroup structure can be found in [47,16b].

There exist similar automorphisms with fixed j2 and j3 axes, which are generated by the angles α2, β2 and α3, β3, respectively.

In the limit (ℏλ, ℏω → 0) the transformations (3.15) reduce to the standard O(3) rotations of Euclidean 3-space by the Euler angles ϕn = αn − βn.

The formulas (3.15) represent rotations of (3,4)-sphere that is orthogonal to the time coordinate t. To define the boosts note that active and passive forms of mutual transformations of t with xn, λn, and ω are isomorphic and can be described by the seven operators (3.1) and (3.2) (e.g., the first term in (3.9), which form the group O(3,4). In the case (ℏλ, ℏω → 0) we recover the standard O(3) Lorentz boost in the Minkowski space-time governing by the operators , where mn = arctanvn/c.

4. Conclusion

In this paper the David′s star duality plane, which describes the multiplication table of the basis units of split octonions (instead of the Fano triangle of ordinary octonions), was introduced. Different kind of rotations in the split octonionic space was considered. It was shown that in octonionic space active and passive transformations of coordinates are not equivalent. The group of passive coordinate transformations, which leave invariant the pseudonorms of split octonions, is SO(4,4), while active rotations are done by the direct product of the seven O(3,4)-boosts and fourteen -rotations. In classical limit these transformations give the standard 6-parametrical Lorentz group.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to acknowledge the support of a 2008-2009 Fulbright Fellowship.