Multi-fiber agreement 15 years later: Degraded working conditions in the Honduran Garment Maquiladora Industry†

†I would like to thank Hilary Goodfriend for her careful revision and useful comments on this article.

Abstract

Fifteen years after the end of the Multi-Fiber Agreement (2005) that deregulated global apparel trade, the effects on exportled underdeveloped economies have been devastating. This article shows that the increase in global capitalist competition due to the conquest of the most dynamic apparel markets has led to a deepening of precarious working conditions in the garment and textile manufacturing industry in Central America. Using the specific case of Honduras, I show that, since the mid-2000s, there have been significant transformations in the labor processes and in wage policies that have put the working class against the wall, reducing wages as well as intensifying and prolonging working days. As a result, the population of garment maquiladora workers is experiencing a generalized social emergency scenario, marked by deep and chronic damages to their physical and mental health caused by working conditions that remain unrectified and ignored by the state and corporate policies.

1 INTRODUCTION

On January 1, 2005, the Multi-Fiber Agreement (MFA) was terminated, ending tariff restrictions that existed previously for apparel global trade. This process of deregulation began a decade before, when the World Trade Organization applied the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) that gave guidance to a 10-year progressive release of tariffs that Europe and the United States had imposed since the 1970s on apparel production coming from Asian countries. These tariff restrictions were completely eliminated by 2005, and international clothing trade went through a process of liberalization. As a result, clothing and textile manufacturing powerhouses such as China quickly became the largest apparel manufacturers in the world, flooding the main global markets, and pushing other export manufacturing economies in which this activity had a significant presence into a situation of economic contraction (Francés, 2011:45; Bair, 2008:4).

One of the regions severely affected by the end of the MFA has been Central America, previously an important manufacturing platform providing clothing for the U.S. market (Legall López & Gómez Carrasco, 2007). With the entry of Chinese and other Asian products into the U.S. apparel market, the garment manufacturing industry in Central America has gone through a process of deceleration, stagnation, and crisis that will be analyzed here in greater detail using the case of Honduras. At the firm scale, there has been attention on the lack of regional linkage of textile production, apparel design, and branding in Central America as the main reason behind the tightening of the apparel industry in the economies of the isthmus during the post-MFA period (Gereffi & Frederick, 2011:77–80), whereas, from a critical perspective that places labor in the center of the lens, Anner (2015) shows that structural transformations in the apparel GVC since mid-2000 has generated a process that he calls “social downgrading,” characterized by greater adverse precarious conditions for manufacturing workers (Anner, 2015).

In the specific case of Honduras, there has been limited literature on the impact of the end of the MFA, most of it focused on analyzing challenges that firms and business agents face in this new global context. The two most outstanding investigations on the subject have been carried out by Bair and Dussel Peteres (2006) and Staritz and Frederick (2012), where the authors coincide in arguing that although some elements of industrial upgrading have occurred as increasing transfer of textile production to Honduras has broadened the production chain in this country since mid-2000, this shift did not generate industrial diversification, but rather a specialization in basic knitwear products such as T-shirts, socks, and underwear, deepening the fragility of the Honduran economy in the context of a fluctuating global economy (Bair & Dussel Peteres, 2006:211; Staritz & Frederick, 2012:274).

However, the viewpoint of these investigations is limited in that it employs a viewpoint that Werner (2016) called firm centered perspective, which views firms as levers of development and social welfare, omitting the effects that the new industrial configuration put forth since mid-2000 in the Honduran maquiladora industry on the labor process and working conditions.1 This perspective does not allow the authors to see the industrial transformation that has taken place in the Honduran maquiladora garment industry because the end of the MFA not only impacts supplying transactions at a firm level; however, it is grounded on greater exploitation rates achieved by capital increasing labor precariousness (Crossa, 2016:195).

It has been 15 years since the end of the MFA, and, as I attempt to prove in this article, capitalist reproduction in Honduras has not given any sign of industrial strengthening or productive consolidation that benefits the working class. On the contrary, extended and deep instability of social reproduction in this Central American country is present in everyday life, showing systematic signs of greater cruelty and barbarism. It is for this reason that, in contrast to research focused on the analysis of firms, which places the maquiladora industry firms as potential levers for national industrial development, this article's main objective is to analyze the impact that the end of the MFA had on the configuration of working conditions in Honduran maquiladora garment industry.

The main argument of this work suggests that large North American corporations have confronted global deregulation of trade in the apparel industry and increasing capitalist competition that has taken place due to the MFA through different mechanisms that seek to increase the rate of labor exploitation in the Honduran maquiladora industry. Among the main characteristics of this transformation, I will place greater attention on analyzing the exponential wage decline, as well as the greater intensification and prolongation of the working day. In other words, the possibility for apparel firms located in Honduras to maintain their active participation in apparel global production chains, despite deepening international capitalist competition, has been achieved, not through business consolidation strategies, but rather through greater violence against the Honduran working class.

The first section of this article gives a historical overview of the maquiladora garment industry development in Central America since the 1980s. This section shows that there are two fundamental periods in this history: The first one begins during Ronald Reagan's presidential term with the U.S. congressional approval of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (ICC) in 1983 and the launching of the Special Access Program in 1987. Both decrees liberalized import tariffs for garments produced in Central American countries, paving the way for the transfer of some segments of the apparel production process from the United States to Central America in the form of maquiladoras. As a result, in the 90s, Central America became one of the most important industrial regions providing garment production to the U.S. market.

The second period began in 2001 with China's entry in the WTO, consolidated in 2005 with the end of the MFA. This second period, analyzed in greater detail, is characterized by a prolonged stagnation of the U.S. market and the vertiginous entry of China into the global production networks of the clothing industry. Consequently, as a response to this increase in international capitalist competition, trade adjustment policies were applied in Central America through the signing of a new trade agreement between United States and Central American countries known as CAFTA-DR (2006). This agreement has had a substantial impact on the Central American garment maquiladora industry, both at a firm level and in the sphere of labor reproduction.

The second section of the article analyzes the development of the maquiladora industry in Honduras during the first period, when this industry grew exponentially in the 1980s and especially in the 1990s. This section analyzes the neoliberal economic policies that promoted the development of the maquiladora industry in the country, as well as the formation and growth of the labor market. As I will show, it was a peak period in the mobilization of workers that created unions and social organizations that still exist today.

The third section presents the main effects that the end of the MFA had on the world of labor in the Honduran maquiladora industry. It shows that, since China entered the WTO in 2001, and especially since mid-2000, the garment maquila industry in Honduras began a prolonged period of stagnation that extends to this day. This crisis stage has led to a process of greater capital concentration in transnational firm corporations that began to dominate the whole maquiladora architecture with full package production. In addition, to survive the whirlwind of global competition, corporations in the maquiladora industry launched a strong offensive against the working class that has deepened and extended labor precarity.

The aim of this article is to analyze the global economy and global production chains, focusing on (?) the sphere of labor and exploitation. There have been many academic efforts that end up justifying labor exploitation by arguing that Global Production Chains have the ability to generate beneficial conditions for underdeveloped economies. However, I will try to show that it is difficult to have an optimistic view of the export-led manufacturing industry in a country like Honduras that is experiencing a situation of deep crisis and social breakdown based on capital's incessant need to increase profits at the cost of workers' very lives in this industry. In other words, insisting on manufacturing export-led maquiladora industry as means of social and industrial upgrading will only perpetuate a fetishist point of view that glorifies an industry that has been responsible for the current national emergency facing the Honduran people.

1.1 Method and data

This research was built based on the analysis of official data on trade and wages in the Honduran maquilas, a follow-up of the various investigations carried out by social and union organizations, as well as qualitative information that I gathered through interviews conducted with a group of 15 Honduran maquila workers in 2014. This group of workers I interviewed was composed of 13 women and 2 male workers, all union leaders from seven different industrial plants. Likewise, four interviews were conducted with women members of non-governmental organizations that accompany the union and labor organizations. The greater presence of women does not respond to the fact that there is a greater presence of women in the composition of the working class in the industry, but rather to the fact that most of the organized groups of workers in the industry are made up of women who have a wide experience in union organization and struggle.

2 IMPACTS OF POST-MFA ERA IN CENTRAL AMERICA GARMENT MAQUILADORA INDUSTRY

The starting point of the garment maquiladora industry in Central America can be located towards the end of the 1980s, when the Special Access Program (SAP) was implemented unilaterally by Reagan in 1987. The SAP, also called Tariff Schedule 807A or Super 807, was described by President Reagan as an effort to “expand free trade and free markets in Central America and the Caribbean” (Rosen, 2002:143). However, SAP cannot be understood without considering the previous approval of the MFA in 1974, aimed at protecting U.S. and European apparel production by imposing quotas on apparel imports coming from developing countries. The aim of the MFA was to prevent Asian countries from flooding developed countries' apparel markets (Goto, 1989).

In this context, SAP created a new international clothing trade regime in which the United States eliminated tariffs exclusively for Central American apparel production only if it was manufactured with fiber made in the United States. This meant that the doors to enter the U.S. apparel market were closed for Asian economies through the MFA; but, the back door to Central American imports was strategically opened in a conditional manner with a significant tariff reduction. SAP was openly aimed at promoting the use of U.S.-made fabrics, thus benefiting U.S. corporations producing yarn and textiles (Chacón, 2000).

The launching of SAP prompted the first growing phase of the maquiladora industry in Central America which lasted until, roughly, 2001 to 2005, years in which China entered the WTO and international apparel trade became completely deregulated and liberalized through the termination of the MFA (Bair, 2008). Between 1989 and 2001, the number of garment maquiladora workers in the Central American Northern Triangle countries (Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras) grew exponentially from 86,000 to 296,000 workers, respectively (Crossa, 2016:148). The United States imports of ready-made clothed coming from Central America and the Caribbean increased sevenfold between 1989 and 2001, making this region the largest U.S. apparel trading partner. The United States imports of clothes from the Central American and Caribbean region went from just over 1 billion dollars in 1989 (6% of total U.S. apparel imports) to 9 billion in 2001 (16% of total U.S. apparel imports). As Table 1 shows, during this first period, the Central American region (CAFTA-DR) became the most important apparel supplier of the U.S. market.

| 1989 | 2001 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| China | 12 | 8 | 33 |

| Vietnam | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| CAFTA-DR | 6 | 16 | 10 |

| Bangladesh | 2 | 4 | 7 |

| Indonesia | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| India | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Mexico | 2 | 14 | 4 |

| Honduras | 0 | 4 | 3 |

| Cambodia | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| El Salvador | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Sri Lanka | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Nicaragua | 0 | 1 | 2 |

- Note: Source: OTEXA, https://otexa.trade.gov/msrpoint.htm

Since the 2001–2005 period, the global apparel trade scenario has changed radically, profoundly affecting the configuration of the Central American maquiladora industry. In 2001, the U.S. economy suffered the so-called dotcom crisis, inaugurating a prolonged process of fragile growth that fell apart with the 2008 financial crisis. Alongside this scenario of economic contraction, China entered the WTO in 2001 and a few years later, in 2005, the MFA came to an end, eliminating further restrictions on U.S. imports of clothing and fiber from Asian countries.2 As a result, Asian production, particularly Chinese and Vietnamese-made fiber and garments, began to flood the North American apparel market.

With the end of the MFA, Central America lost the leading place as a U.S. apparel trade partner. As of 2001, China became the clothing factory of the world, the largest clothing and fabric supplier of the United States, well above all other countries. In 2001, China represented 8% of U.S. clothing imports, and by 2018, this percentage had grown to 33%, with 15% representing Vietnamese imports, whereas Central American and Caribbean countries reduced their participation from 16 to 10% during this same period (see Table 1). In other words, there was a widespread relocation of apparel production that made the Asian region, especially China and Vietnam, the manufacturing region for the world's greatest apparel markets.

This work does not intend to analyze capitalist development in China, although it is important to mention that China went through an industrial upgrading process motivated by an advantageous insertion in global apparel trade once the MFA ended. The Chinese economy, not only specialized in the assembly industry, as in the case of Central America in the form of a maquiladora industry; but, the production process in the Asian country has gone through a course of vertical integration involving the whole production process, with firms controlling their own design and distribution, producing natural or chemical fibers, as well as assembling clothes.3 All the main stages of the production chain are being carried out in this Asian industrial powerhouse by combining high value- added production with labor intensive links of the chains, making it possible to exponentially increase productivity, acquiring relevance in the global apparel markets and generating increasing pressure on other apparel export-led economies such as the Central American countries (Gereffi & Frederick, 2011).

This sharpening of capitalist competition caused by the entrance of Asian economies with large concentrated and vertically integrated corporations led to a new stage in global apparel production chains. This pressure mainly impacted U.S. and European manufacturers, which have proven to be the most affected companies, to the point that some U.S. fabric manufacturers have succumbed to the tremendous competition, whereas others have deeply restructured their productive architecture. The U.S. apparel corporations had to respond with a new, qualitatively different agenda of productive relocation that, among other things, transferred the stage of fabric production to the maquiladora manufacturing countries in Central America. As a result, highly automated textile production began to relocate to Central America, thus expanding the process of apparel production in the maquiladora countries and generating incipient industrial clusters in this region. In other words, the apparel industry in the export-led maquiladora countries went from being a purely assembly and garment industry during the 1990s—in the first phase—, to becoming Full Package manufacturers that combine fabric and garment production (Bair & Dussel Peteres, 2006).

This increasing process of territorial integration was made possible by the implementation, in 2006, of the Free Trade Agreement between the Dominican Republic, Central America, and the United States (CAFTA-DR) which changed the “rules of origin,” necessary for the United States to import apparel products from Central America and the Dominican Republic. Parity was established with the yarn forward rule in NAFTA which, allowed the United States to import clothing made with fabrics produced in Mexico. These rules of origin were extended to Central American and Caribbean countries, so that apparel imported by the United States could be made with fabrics produced in any of the CAFTA-DR countries, meaning that the garment manufacturing industry located in the Central American countries could be supplied with textile fabric produced in this same region.

The first notable consequence generated by the implementation of CAFTA-DR in the maquiladora industry was the increase of the capital concentration and centralization process through company mergers. During the 90s, the maquiladora industry was made up of a much larger number of medium-size companies that operated under an outsourcing model, whereas from 2005 onwards, there has been greater capital centralization, in which big firms have taken direct administrative control over the manufacturing process and are now owners of big textile mills and garment factories in the region. As a result, the percentage of workers began to concentrate more and more into fewer corporations. The cases of Fruit of the Loom, Gildan, and Hanes, the three biggest apparel corporations in the region nowadays, are examples of Full Package firms that previously operated through a network of “independent” outsourced companies and are now integrated vertically, controlling the entire production process themselves, from fabric production to the garment manufacturing industry. Only these three corporations together concentrate approximately 30% of the total maquiladora workers of Central American North Triangle countries in 2016.

These large corporations increased their direct presence in Central American as they took advantage of CAFT-DR trade rules and installed their own textile mills in the region, especially in Honduras, to create industrial clusters and increase productivity rates. In other words, to generate a new pattern of emerging industrial upgrading that involved a transition from an assembly to a Full Package production model.

From the hegemonic and mainstream view of Global Production Chains, this transition should be considered positive, as it shows signs of greater performance, growth, and industrial articulation in the Central American region. However, as I will show in the following sections using the case of Honduras, this conversion of the maquiladora industry toward the control of vertically integrated corporations has had a profound impact on the labor sphere, which suffered deep transformations aimed at intensifying and prolonging the working day. In other words, rather than benefiting the domestic growth and workers, industrial upgrading in the Central America maquiladora industry has meant the increase in the rates of exploitation and greater control of transnational corporations.

3 THE MAQUILADORA INDUSTRY IN HONDURAS: NEOLIBERAL POLICIES DURING THE 90s

In “Reagonomics for Honduras”, there is a clear approach against the continuity of the Welfare State as well as against the incipient ISI model being held in the country at the time. The aim of this neoliberal agenda was to generate new conditions of capitalist reproduction that matched corporate necessities of the new global economic architecture. Among the notable elements of the program, the most relevant was the transfer of investment incentives under the protection of industrial investment laws to favor export production while gradually reducing incentives for domestic manufacturing. What followed during the 90s was a cascade of neoliberal structural adjustment policies that put an end to the incipient nationalist industrial project promoted by the State, dismantled the organized working class and made the maquiladora industry the core of the Honduran economic organization (Hernandez, 1983:60).Peace and security in the Caribbean Basin are in our vital interest. When our neighbors are in trouble, their troubles inevitably become ours. What these countries need most is the opportunity to produce and export their products at fair prices. That's what the Caribbean Basin Initiative is all about. It offers them open markets in the United States and initiatives to encourage investment and growth. Far from a handout, the proposal will help these countries help themselves. Trade, not aid, will mean more jobs for them and more jobs for us.5

Between 1984 and 1998, the Honduran federal government signed several constitutional decrees that made the Honduran territory a free zone so that transnational corporations could operate under tariff exceptionality. Signed in December 1984, Decree 35 created the Temporary Importation Regime (RIT) to take advantage of the supposed tax exemptions and tariff benefits offered under the Caribbean Basin Initiative (Moncada, 1995). A few years later, in 1987, Decree No. 37-87 approved the creation of Industrial Processing Zones (ZIP), which extended the tax exemption to other municipalities in the northern region of the country near Puerto Cortés. Under this new regulation, industrial parks that were previously controlled by the state owned National Port Company became private property under the hands of local rentier oligarchs that have become multimillionaires over the years (Kennedy, 1998).

Economic transformation in the country acquired greater strength in the 1990s with the adoption of a much more comprehensive neoliberal economic policy program. In 1990, a month after assuming presidency, Rafael Leonardo Callejas made a public statement in which he announced that the Honduran economy was in “bankruptcy.” As a solution, congress passed a bill called Economic Structural Planning Act (Executive Order 18-90), also known as “paquetazo” designed by the IMF and the IDB. The program can be summarized in two main objectives: one was to create the conditions for Honduras to have the financial capacity to pay off foreign debt, and the other was to generate profitable spaces of accumulation and investment for transnational corporations (Arancibia, 2013).

Articulated around this new agenda of neoliberal economic policies, the garment maquiladora industry in Honduras began to grow exponentially in the 1990s. According to official data, between 1993 and 2002, the number of jobs in this industry went from 30,000 to 106,000 workers, respectively, whereas Added Value in this same period increased by 10, from 500 million Lempiras to 5,300 million Lempiras, respectively.6 These were the thriving years of the maquiladora industry in which the northern cities of the country, especially those located close to Puerto Corts, grew significantly due to the presence of this industry.

A fundamental feature of this first phase was the massive incorporation of young women. In the early 1990s, 80% of workers in the Honduran maquiladoras were young women, commonly rural migrants moving to the cities and getting massively employed in this export manufacturing sector (Beneria, 1999; CDM, 2011). Cities like Choloma that were previously small, agriculture-based towns, became the maquiladora epicenter, with a leading presence of industrial parks and extended working class neighborhoods.

4 CAFTA-DR AND THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE HONDURAN MAQUILADORA INDUSTRY

The increase in global competition in the apparel industry caused by the end of the MFA and prolonged stagnation in the U.S. economy that began with the dotcom crash has caused a prolonged crisis in the Honduran maquiladora industry, because of which there has been a decrease in the number of establishments from 167 in 2005 to 127 in 2018. Similarly, the number of workers stagnated from 106,000 in the year 2000 to 104,000 in the year 2018.

In contrast with the previous period of 1990–2001, when the biannual growth of U.S. apparel imports from Honduras was 27%, from 2001 to 2016, these imports timidly increased from 2.4 billion dollars to only 2.8 billion dollars, respectively. During this process of stagnation, Honduras has gone through an export hyper-specialization trend where most of its exports have concentrated in knitted T-shirts that represented 40% of U.S. apparel imports from Honduras in 1995, whereas in 2018, they reached 70%.7 In other words, the maquiladora garment manufacturing industry in Honduras has tended to specialize in a few labor intensive simple-made products that generate little added value. This high degree of productive specialization indicated the degree of industrial fragmentation within the manufacturing industry in Honduras, making it highly vulnerable to U.S. market declines.

With the launching of CAFTA-DR and the extension of the apparel rules of origin, knitting mills have been installed in Honduras, forming industrial clothing clusters in the northern industrial region of the country. As a result, Honduras went from being a fiber importer to producing it domestically and becoming a yarn importer from the United States. There are currently 15 textile plants in Honduras that employ approximately 8,700 workers −8% of the total maquiladora employees. This fabric is mainly used in the maquiladora factories located in the country and around Central America. That is to say that Honduras has become the largest fabric supplier of the manufacturing maquiladora plants located throughout the isthmus region.

A large part of the fabric mills that have been installed in Honduras are vertically integrated North American firms that operate as Own Brand Manufacturing companies (OBM). Unlike the traditional outsourcing model that prevailed during the 1990s, where firms outsourced garment production, Full Package commercial corporations have become more relevant, as 6 of the 15 textile plants that have located operations in Honduras since 2006 are U.S. corporations employing 1,000–3,000 workers each.

The exemplary case of an OBM corporation that has increased investments significantly since 2005 is the Canadian company Gildan Activwear, which has two fabric production facilities and five garment plants in the country. This company, along with Fruit of the Loom and Hanes Brand, concentrate 23,000 workers, that is, 25% of the total garment maquila workers in Honduras. ELCATEX is another important example of a fabric manufacturing company owned by a Honduran corporate group called Grupo Lovable that is run by an oligarchic family that also owns a garment plant called Genesis Apparel, as well as the nation's biggest and oldest industrial parks called ZIP Choloma located near Puerto Cortés (RSMH and EMIH, 2012).

These OBM's have expanded significantly with Full Package operations in the whole region of Central America. The most illustrative example is the case of the Fruit of the Loom Company, which has around 27 plants worldwide. Eight industrial plants in Honduras employ approximately 13,000 workers and seven industrial plants in El Salvador employ approximately 11,000 workers. It also has direct production in Mexico, particularly in the Yucatan Peninsula and outsources production in other regions of that country. In Central America and Mexico together, Fruit of the Loom employs approximately 27,000 direct workers (RSMH & EMIH, 2012).

The expanded process of capital concentration in the apparel maquiladora industry in Honduras shows that the end of the MFA (2005) and the signing of CAFT-DR (2006) was a trade policy initiative that has benefited mainly large North American corporations or Honduran companies owned by local oligarchic families like Canahuati or Kattan, Rosenthal, Amandi, among others. The extension on Rules of Origin and the consequent relocation of textile mills in Honduras, far from generating better conditions of domestic industrial development, have further fractured the country's industrial composition, leaving the bulk of exports in the hands of large transnationals. In this sense, it is important to mention that the process of incipient industrial upgrading carried out in the maquiladoras through the growth of Full Package Own Brand manufactures has brought no signs of positive growth. Instead, it has deepened the subordinated and dependent condition of this economy to the needs of the U.S. market.

5 INTENSIFICATION AND PROLONGATION OF THE WORKING DAY: REORGANIZATION OF LABOR PROCESS AND WAGE POLICIES

Although capital concentration in the garment maquila industry described in the previous section is an important element to be considered to understand shifts occurring in this industry as a response of North American and Honduran oligarch corporations to U.S. market stagnation and growing Chinese competition, the main lever behind this recent transformation in the Honduran maquiladoras has been the increase in the rate of labor exploitation. This section will show that the reduction of wage purchasing power as well as the intensification and prolongation of the working day have been a central part of the new industrial arrangement put forth in the Honduran maquiladora industrial since the mid-2000s.

The first important thing to note is that the number of workers and exports in the Honduran garment maquila industry have stagnated since 2001, demonstrating that this industry has lost dynamism in the country because China entered the apparel global market. As Table 2 demonstrates, there were 2000 workers less in 2017 than in 2002, whereas exports did not grow much higher than 3 billion USD during this same period.

| Number of workers in garment maquilas (thousands) | Garment exports (Millions USD, constant value 2009) | Exports by worker (Millions USD, constant value, 2009) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 32 | 733 | 23 |

| 1997 | 86 | 2,254 | 26 |

| 2000 | 95 | 2,949 | 31 |

| 2002 | 106 | 3,069 | 29 |

| 2006 | 101 | 3,064 | 30 |

| 2009 | 84 | 2,600 | 31 |

| 2012 | 96 | 3,062 | 32 |

| 2017 | 104 | 3,117 | 30 |

- Note: Source: Data on exports was gathered from the Observatory of Economic Complexity, https://oec.world/en/. Data on number of workers was gathered from Honduran National Bank, https://www.bch.hn/index.php

But stagnation figures do not explain everything. Behind this meager macroeconomic growth hides a profound transformation in the industry, both at the level of capital ownership, as we showed previously, as well as in the world of labor, which has been deeply attacked by a corporate application of wage and labor process reorganization, because the first years of the 21st century aimed at intensifying and prolonging the working day.

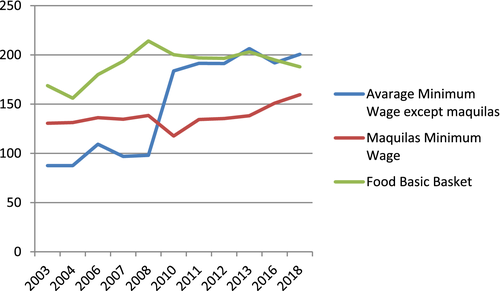

There has been significant nominal wage increase in Honduras, especially since 2008 when President Zelaya decreed a 60% minimum wage increase for all sectors except the maquila industry. However, as shown in Figure 1, despite the increase in wages, the price of the Basic Food Basket—which does not include services—continues to be higher than the wages, which indicates that the increase in wages has been accompanied by an inflation process that limits wages from reaching the necessary purchasing power for basic social work force reproduction. It is not by chance, therefore, that despite a significant increase in the minimum wage, 62% of households in the country remain in poverty.8

If the national minimum wage has been kept below the price of the basic food basket, the minimum wage in the maquila is even lower, significantly lower (Figure 1). Not only did the maquila minimum wage fall below the national minimum wage. It fell far below the basic food basket price, to the extent that in 2018 the maquila minimum wage served only to acquire 84% of the food basic basket. If we consider the demand of Honduran unions to incorporate services in the Basic Basket, the prices would increase to 500 Lempiras a day, which means that wages in the country and in the maquilas fall well below labor force value.9

We are paid a weekly base wage of approximately one thousand Lempiras and a bonus of 190 Lempiras, but they use the bonus to control our work because if you do not comply with 100% production, they do not give you bonus and they punish you. To reach the bonus we press ourselves and work more than 100% required…they use it to pressure us more. (Karen, Gildan Activwear worker, interview, Progreso, Honduras, 2014)

Sometimes we need to stay 15 more minutes to finish the production goal or even sacrifice part of the lunch time to not fall behind, but if we leave one or two minutes before lunchtime they call your attention and they punish you by taking you off punctuality bonuses. There is a tight control of the time when it suits them (Vilma, Fruit of the Loom worker, interview in Villanueva, Honduras, 2014).

Many workers do not take the half hour they are given for lunch because they need to finish production goals, because companies have found in production goals the best way to control workers. If a worker does not meet the goal, they will call her attention, give her written warnings or penalize her by taking days off. This is harmful because a maquila worker lives from hand to mouth. That is why the situation in the maquilas today is extremely serious (Maria Luisa, CODEMUH member, interview in Choloma, Honduras, 2014)

To increase production at all costs, maquila companies have applied two fundamental levers on the floor of the factories: Implementing what is known as four by four or four by three working day regimes and applying modular teamwork production in the labor process.

The four by three regime refers to the organization of the working week with 12 hr working days during 4 days and 3 a day rest. This organizational form was created by the biggest maquila manufacturing corporation in Honduras, Gildan Activwear, in the first years of the 21st century. In 2003, the Maquila Solidarity Network did a research on this company and showed, among other things, that four by three work shifts aim to “making the work day more flexible in order to increase productivity and save money” (MSN & EMIH, 2003:41). In 2012, another Honduran Maquiladora Union Network and Honduran Independent Monitoring Team investigation showed that this working day regime had become widespread in the garment industry, with at least one third of the working population from different companies hired under this condition (RSMH and EMIH, 2012).

Many workers agree to the 4 by 4 shifts, especially women, because it gives them time to be at home and be able to spend more time with family and their children. But the 4 by 4 serves the company because they no longer have to pay overtime and they don't pay vacations or holidays, so in the long run it is time and money that is being taken from the worker, but the wear and tear of working 12 hours is a lot higher (interview with María, Lear Corp, Choloma, Honduras, 2014).

Legally, every extra hour should be payed 25% more during the day and 75% more during the night. However, with the four by three schemes, maquila companies avoid having to pay overtime while they have the factories running all day and night. In addition to this, workers cannot stay permanently in one schedule, meaning that every now and then they get moved from daytime to nighttime shifts. As the Center for Women's Rights (CDM) showed, this labor process organization violates provisions of the Honduran Labor Code, where it is recognized that the ordinary working day may not exceed 8 hrs a day and 44 hr a week, whereas during the night, it cannot exceed 6 hr per day and 36 per week. This has caused profoundly negative effects on the physical and mental health of workers (CDM, 2017:44). This is why María Luisa Regalado was explicit in mentioning that “4 by 4 shifts are illegal, the Labor Code is clear in saying that a work day is 8 hours per day: Eight hours a day from Monday to Friday and four hours on Saturdays” (Maria Luisa, CODEMUH member, interview in Choloma, Honduras, 2014).

Another important mechanism used by maquiladora companies to increase production is the modular organization of the labor process, where production goals are set for a group of workers who must work at the same pace, with the need to meet the same production rate. Productivity bonuses are given to the group that obtains the best productivity standards, whereas supervision is done by the same workers when pressed to comply with the production levels required by the company. Workers, instead of meeting individual goals, are subject to a dynamic of great pressure among team members and between teams.

The idea that teamwork has been used as a corporate mechanism to increase labor intensity was confirmed by Zayda when she mentioned that,Production goals are a particular characteristic of exploitation in the maquiladoras. When they are assigned to groups, that is, when they set collective and non-individual goals, the pressure to reach them comes from the same workers, so that anyone who fails to reach them face violence from their coworkers and from management (CDM, 2017:36).

At the Pinehurst factory we have team goals; we do not have an individual production goal. We are around 15 people in each group and we need to produce at the same pace. This teamwork is a need that serves the company rather than the workers, because you have to work just like everyone else. If someone works less, the person next to you will complain against you, so it's your own coworker that demands from you. Your coworkers pressure you because the bonus is given to the team and that becomes the way the company guarantees that every person works at maximum speed (interview Zayda, Pinehurst worker, Colonia Planeta, Cortés, Honduras).

The maquila companies and the government have insisted in telling people that they have to lay off many workers due to the world economic crisis, but we have been able to observe that the volume of production has not reduced, but rather the number of people working. That is why teamwork production goals were invented, because a production line that was previously made of 20 people is now a team of 15 people having to produce the same amount. So the demand for the worker has increased much more in recent years (Maria Luisa, CODEMUH member, interview in Choloma, Honduras, 2014).

With teams, the number of workers has been reduced but the production goals are the same or greater. Many female workers have complained about the pressure they face to meet the production goal, which they said affect negatively their ability to maintain a relationship of solidarity with their co-workers. Workers said that the entire team lost income when someone got sick, was pregnant and/or worked more slowly than others. They noted that the teamwork system transfers responsibilities that were previously from the supervisor to the teams themselves (MSN, 2012)

Like other changes, teamwork is a corporate motivation by the maquiladora companies to increase production without raising wages. In this condition, all workers must produce to the fullest and none will earn more for it. That is to say, workers who used to produce faster and receive bonuses for it, will not receive it now. They must work at the same pace and with the same intensity, without receiving the income they received when the goals were individualized. However, workers who produced at a slower pace should now increase their production, although they will not get a greater compensation for it. This change increases the deterioration of workers, producing negative health consequences, as well as exacerbating pressure among the same workers who, in many cases, depend on increased production to receive higher incomes.

A worker makes up to 60,000 repetitive movements in a working day. This is why health problems in the maquilas are so serious. Musculoskeletal disorders are the most common and the most serious, but there is also problems related to depression, stress and anxiety. This happens to young women, most of the workers are very young, between 20 and 35 years old, and are not in the age of having to suffer from these health problems. That is why there are workers who say that they only step into the factory and they feel life flying away, they feel the pressure on them from the first minute they start the shift (Maria Luisa, CODEMUH member, interview in Choloma, Honduras, 2014)

In their struggle for a disability pension allowance, many workers have faced a discriminatory health system that in every sense seeks to separate health, prevention, and working conditions. This is why organizations have been emphatic in affirming, as CODEMUH does, that the serious occupational health problems that currently exist among the Honduran working population happen “with the consent of the state, which despite having a legal framework from the Constitution, ratified Conventions with the International Labor Organization, [and] laws such as the Labor Code, Health Code and Social Security Law, disregards monitoring enforcement” (Pérez Pantoja & Castro Díaz, 2018:57).

Factory doctors give acetaminophen for everything, if you have a stomach pain they'll give acetaminophen, for headache, they give acetaminophen. Could it be that this is such a miraculous pill that it cures even the body aches that work generates? But people get sick not because they want to, but because they don't let us go to the bathroom, they don't let us drink enough water, many women suffer from colon problems because they are so pressured to finish their production goals that they don't go to the bathroom. They don't go to the bathroom and in the long run that causes illness. But instead of seeing it that way, the doctor in the plant gives us acetaminophen to calm the pain… it's a corrupt health system that fails to take responsibility for the health problems suffered by workers (interview with María, Lear Kiungshin Corp worker, Choloma, Honduras, 2014).

When diagnosing occupational diseases as common diseases, employers avoid their responsibility of paying for the costs of treating impacted workers or even of paying the corresponding compensation established by law, generating a system of corruption and impunity that falls on the backs of the workers who end up having to assume the costs of this omission. In other words, not only are companies avoiding the enforcement of preventative policies that could modify labor process organization; but, once the worker is psychologically and mentally affected, they refuse to apply reparations, despite the fact that it has been caused by precarious working conditions on the production floor.

Impunity and corruption in this field respond to companies' incessant need to maintain high levels of production and low wages. Preventing and repairing damages would mean that companies would have to reformulate production processes based on the respect for workers' rights; but so far, they have not been willing to negotiate an appraisal of their profits. On the contrary, the more subjugated the working population is, the greater their interest in maintaining investments in Honduras.

6 CONCLUSION

This article analyzed the effects that the end of the MFA has had in the Honduran maquiladora industry, especially the changes it has caused in the labor process and the working class. It demonstrates that the incorporation of Asian economies, especially China, in the global apparel trade has generated an international scenario of deeper capitalist competition resulting in the profound transformation of other apparel export led economies such as Honduras. One of the main changes in the Honduran maquiladora industry is a growing capital concentration process propelled by a Full Package production model controlled by so called brand-manufacturers that have currently displaced the outsourcing industrial model that prevailed in this industry during the 1990s. The second and most important transformation has been the change in the labor process marked by the greater intensification and extension of working hours. This last element has been achieved by the maquiladora companies with the use of a wage policy in which the incomes of the workers has been conditioned to production goals, forcing workers to produce more in less time. In addition, there has been an extended use of the four by three working week policies, under which working hours extend to 12 hr a day. Finally, companies have implemented team productions goals to intensify the production. As a whole, this transformation of the maquiladora industry in Honduras has generated a situation of social emergency characterized by severe damage to the physical and psychological health of maquiladora working population, which has not been addressed or resolved by maquila companies or the State, but rather has been ignored and veiled by networks of complicity and impunity that end up benefiting the greater accumulation of private capital in large corporations.

ENDNOTES

- 1 Another investigation on the Honduran maquiladora industry during post-MFA era was carried out by Rafael De Hoyos, Bussolo, and Nunez (2008), in which the authors claim that this industry has the potential ability to reduce poverty in the country's labor market. The article argues that between 1990 and 2006, Honduras went through a process of significant poverty reduction caused by the benefits brought by the maquiladora industry growth. It emphasizes the fact that workers in this industry received incomes above the national average, in addition to experiencing a scenario of less wage discrimination against women. In this sense, according to the authors, this industry is generating greater social benefits for the active working population compared to the conditions that predominate outside the maquiladora labor market. However, after 12 years of having published the article, the main argument is evidently unprecise as real facts have shown that maquiladora wages have lagged behind the national average minimum wage and, despite the leading role of this industry in the national economy, Honduras is currently the second country with the highest poverty rate in Latin America. In other words, it makes no sense to argue that the maquiladora industry has become a means to reduce poverty.

- 2 This global liberalizations of apparel trade covered all products which were subject to MFA or MFA-type quotas OMC, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/texti_e/texintro_e.htm (consulted 11/01/2020)

- 3 A clear example in this matter is the Shandong Ruyi case, which has 20,000 workers operating from the production of yarn to clothing. In August 2012, this company announced the acquisition of Cubbie Group, one of the largest cotton producing companies in Australia. Interestingly, this example is not an isolated case. Like this, we can mention many cases Chinese apparel firms that have been gone through Full Package integration

- 4 For more on “Reagonomics for Honduras,” see https://nuso.org/articulo/la-reoganomics-para-honduras/ (January 26, 2020)

- 5 Reagan's presentation during “White House Ceremony Marking the Implementation of the Caribbean Basin Initiative.” Retrieved from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/research/speeches/100583a (January 27, 2020)

- 6 Data gathered from the Honduran Central Bank https://www.bch.hn/actividad_maquiladora.php

- 7 This percentage is made up of T-shirts for men and women produced with knitted fabric.

- 8 Data gathered from Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2020), Reporte de la metodologia para medir la pobreza monetária em Honduras, pg5. Consulted in: https://www.ine.gob.hn/V3/imag-doc/2020/01/Enero-2020-Cifras-Revisadas-Pobreza-en-Honduras-30-enero.pdf

- 9 Unions in Honduras have argued that the Basic Basket of Goods and Services in Honduras costs 15,000 Lempiras, twice the amount of the official data on Basic Food Basket price, which is why they demand the government to broaden the calculation and not only incorporate basic food products. Consulted in: https://www.elheraldo.hn/economia/1304914-466/entre-5800-y-6100-lempiras-cuesta-la-canasta-b%C3%A1sica-seg%C3%BAn-sde

Biography

Mateo Crossa Niell PhD in Latin American Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) and in Development Studies at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas (UAZ). Research interest is focused mainly in the study of labor and maquiladora industry in Central America and Mexico through the lens of critical Latin American political economy. Among his publications stands the book Honduras: maquilando subdesarrollo en la mundialización (Honduras: Manufacturing Underdevelopment in Globalization). He has also participated in multiple film projects such as the documentary film Made Honduras that portrays the life and labor rights organization of maquiladora workers in Honduras.