Exploring relationship between degree of unionization and firm productivity in Indian listed firms

This study explores the effect of degree of unionization on the firm productivity using the modified Cobb–Douglas function in the context of India.

Abstract

This study is among the first to explore the relationship between unionization and firms' productivity, defined as sales per employee, and profitability per employee in India. The Indian context is important given the structural changes in Indian economy post-1991 (liberalization and movement from dirigisme to an open economy), the unique sociocultural context of Indian unions and growth and size of economy. The final dataset of the study consisted of 91 largest firms listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange in India. The data were collected from audited annual reports and analyzed using a modified Cobb–Douglas function. It was found that the degree of unionization, which is percentage of employees who were member of a trade union, had an overall positive impact on the firms' productivity. Contrary to the dominant view of private sector firms being more productive, we found empirical evidence for the effect of unionization on productivity being greater for public sector firms.

1 INTRODUCTION

This Sanskrit maxim exalts the importance of power in the collective in this age of Kali.1 The analogous phenomenon at the workplace with respect to the collectives is the trade unions in the contemporary times. Trade unions are often conceptualized as collectives, which are formed by the employees to safeguard their rights against the employers or the state. The impact of unionization and collective bargaining on firm productivity, output quality, and firm survival is one of the most contentious topics in labor economics (Freeman, 2005; Hirsch, 2003; Sojourner, Frandsen, Town, Grabowski, & Chen, 2015). Several studies have looked at the effect of unionization on productivity at both aggregate economy (Brown & Medoff, 1978; Freeman & Medoff, 1984; Hirsch, 1991; Hirsch & Link, 1984) and firm-level (Addison, 2005; Bhandari, 2008; Clark, 1980). Scholars have also inquired into the sectoral differences of trade unions (Baldwin, Skudelny, & Taglioni, 2005; Bhattacherjee, 2000). Despite research in varied contexts, our understanding of the effect of unionization on productivity and the causes of the same is still limited and suffers from the bias of near exclusive focus on developed countries. Developing countries like India differ from a developed country like the United States on multiple parameters like percentage of employment in the organized sector; capital intensity of production; average level of wages and sociocultural expectations of employers and employees from each other. India is a unique context for conducting a study on the impact of unionization on productivity because of its huge population; size of economy; high sophistication of parts of its economy; history of unionization which can be traced back to late 1800s; unique union traditions and multimillennium long cultural traditions which have shaped mutual expectations of employers and employees. Indian economy is still undergoing transition from being a centrally planned economy, with the public sector occupying the commanding heights, to becoming a market economy. The process of transitioning to a market economy, which began with liberalization in 1991, is still not complete as suggested by the presence of public sector undertakings and government controls in some of the key sectors. Additionally, India is one of the few countries which has followed a trajectory of services-led growth without becoming a manufacturing powerhouse, which is contrary to the traditional model of sequential transition from an agrarian to manufacturing to a services economy (Bhattacherjee & Ackers, 2010).

Topics explored on unionization in the Indian context include wage premium for unionized workers (Bhattacharjee, 1987); the nature and content of collective bargaining agreements; and the impact of legislative provisions (Bhattacharjee, 2005) and the trends of unionization in public versus private sectors (Sodhi, 2013). To the best of our knowledge, we are not aware of any empirical work in the recent times that has explored the impact of degree of unionization on firm productivity. We can at best hazard a guess that data limitations might have inhibited explorations degree of unionization on the firm-level productivity. The question of exploring unions' role in firm productivity acquires additional importance in India because (a) the country is transitioning from being a centrally planned economy to a market economy; (b) government is identifying manufacturing as a driver of the economy (e.g., Make in India campaign); (c) there is a pronounced negative shift in attitudes toward unions by employers, governments and the general public (Varkkey, 2015); and (d) there is increasing clamor for labor flexibility and deregulation (Sundar, 2008). Empirical investigation of the effect of the degree of unionization on firm productivity is necessary for proper policy formulation that aim to balance right to form collective institutions like unions with the need for growth, especially against the backdrop of union decline (Balasubramanian, 2015).

We contend that with respect to trade unionization and productivity, the two fundamental questions are: (a) Does the presence of the trade unions improve or inhibit the firm-level productivity? and (b) Given that trade unions are present, does the degree of unionization improve or inhibit the productivity of the firm? We argue that the first question reduces the complex phenomenon of unionization into the mechanical categorization of union presence and absence in organizations without looking at the penetration levels of unions. This binary categorization also ignores social realities of collectivistic countries like India, where evidence suggests that institutional norms of employers and employees, rather than concerns about fair wages and productivity, lead to presence (absence) of unions in firms (Sarkar & Charlwood, 2014). Hence, the article focused only on the second question namely, Does the degree of unionization impact the productivity of the firm?

The effect of degree of unionization on firm productivity borrows from existing literature that identifies internally consistent and coherent Human Resource Management systems as a source of organizational productivity and competitive advantage (Arthur & Boyles, 2007; Datta, Guthrie, & Wright, 2005). Unions can be conceptualized as a subset of the human resource system of the organization—which represents the interests of its constituents to either the employers or the state (Bain & Price, 1980)—the difference being that they are organized by and for employees, rather than employers. There is an abundance of research on the degree of unionization and its various effects primarily in the context of developed economies like the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries (Blanchflower & Freeman, 1992; Hooghe & Oser, 2016). However, there is a dearth of similar research in the context of developing countries like India (Das, 2000). Our research provides contextual novelty and attempts to quantify the effect of the degree of unionization on the productivity of the firm. The theoretical framework of our article is based on the modified Cobb–Douglas function that contends that output is dependent on the physical capital and labor and assumes the quality of the labor to be uniform. In line with Toke and Tzannatos (2002), we contend that the degree of unionization would positively impact the productivity of the firm in India. The analysis is based on secondary data collected from the firms' audited annual financial statements.

The article first discusses the germane literature on the relationship between unionization and productivity and the unique nature and history of unions in India. This is followed by an explanation of the sources and characteristics of the data collected; the rationale underlying our choice of the sample set used for analysis and the variables (measures) used in the study and the method of analysis of the data. After presenting the methodology, we highlight and discuss the findings of our analysis. Finally, we conclude with identifying the salient implications and limitations of our research.

2 GERMANE LITERATURE

There is broad agreement among the scholars and practitioners that unionization acts as a pressure group on the different stakeholders including the government and the employers for protecting or advancing the interests of the workers (Bennett & Kaufman, 2004). Scholars further agree that trade unions affect certain attributes of a firm most notably wages, productivity, working conditions, managerial effectiveness, overall morale of the workforce, procedures, and discipline at workplace (Addison, 2005; Freeman, 2005; Hirsch & Addison, 1986; Hirsch & Link, 1984; Pencavel, 1977) albeit it is beyond the scope of this research to assess in detail each of these aspects. Freeman (1976), Brown and Medoff (1978), and Freeman and Medoff (1984) opened the Pandora's box of questions regarding the impact of unionization on firms' productivity with their seminal studies that suggested positive impact of unions on firm productivity. These findings have been challenged by later studies that suggest that productivity growth is slower in industries with higher union coverage (Hirsch & Link, 1984). Based on empirical evidence and ideological proclivities, scholars, and policy makers can be divided into two broad camps namely, one camp alleges that the trade unions tend to have a negative effect on the productivity of the firms while the rival camp claims that the trade unions tend to have a positive effect on the productivity of the firms. The debate in this field has led to abundant research in varied contexts and settings to assess the impact of trade unions on the productivity (Freeman, 2005).

The role of unions on productivity can be analyzed using the two faces of unionism thesis—“muscle face” and “collective voice face” (Freeman & Medoff, 1984). The “muscle face” suggests that unions use their collective bargaining power to extract economic gains from employers while the “collective voice face” presents unions as an avenue for the employees to express their voice. Scholars suggesting negative relationship between unionization and productivity focus on the “muscle face” and view unions as monopolistic organizations that aim to improve employee compensation at the cost of free play of market forces, thereby reducing productivity and imposing costs. They also doubt the validity of the “collective voice face” (Hirsch & Addison, 1986; Metcalf, 1990; Schnabel, 1991).

Scholars attributing positive role to unions focus on the “collective voice face” and suggest that unions facilitate communication between workers and management leading to better collaboration; less turnover and increase in average tenure (Freeman & Medoff, 1984). Increased retention leads to greater on-the-job learning thereby leading to a positive impact on organizational productivity (Belman, 1992; Doucouliagos & Laroche, 2003).

Empirical evidence has also been equivocal in settling the issue. Pencavel (1977), Brown and Medoff (1978), Allen (1984), Freeman and Medoff (1984), Machin (1991) and Barth, Bryson, and Dale-Olsen (2017) identified a positive impact while Clark (1980), Clark (1984) and Boal (1990) found that unions had zero or negative impact on firm productivity. Interestingly, research in same country has also led to contradictory findings. For example, positive (negative) relationship between unionization and employee-level productivity has been identified in Japan, Germany, and China by Morikawa (2010), Fitzroy and Kraft (1987) and Budd, Chi, Wang, and Xie (2014) (Brunello (1992), Schnabel (1991) and Yang and Tsou (2018) and Bradley, Kim, and Tianc (2016) (both in China).

Meta-analysis too has failed to resolve this debate. Hirsch (2004) has claimed that “there exists no strong evidence that unions have a direct effect on productivity growth” (p. 431). Doucouliagos and Laroche (2003) and Doucouliagos, Freeman, and Laroche (2017) indicated that the relationship between degree of unionization and productivity is contingent upon country, industry and the specific period (time) for which the relationships were studied. Drilling down to specific countries, they estimated the effect on unions to be zero in the United States, negative in the United Kingdom and Australia and positive elsewhere. From the foregoing discussion, it is evident that there is a wide variation in the productivity effects of trade unions in different contexts. Besides contextual factors like country or industry, the differences in findings can also be attributed to variations in measures or estimation of output and use of simplistic binary categories of union presence and absence (Freeman, 2005). Hence, there is a need to study the impact of unionization on productivity in new contexts—especially in the context of developing nations undergoing transition and maintain consistency in estimation techniques to ensure comparability. Consequently, we contend that India seems to be an apposite case for this inquiry as its context is unique.

3 THE UNIQUENESS OF INDIAN CONTEXT

India plays an important role in the global economy. India probably accounts for the largest source of surplus labor in the world and it is expected to have a share of 18.6% of the global labor force with close to about a billion individuals in the 15–64 years age group by 2027 (Giudice & Lu, 2019). With its large population and booming economy, it is one of the major sources of foreign investment. As per the United Nations estimate, India has attracted investments of close to $22 Billion in the first half of 2018 (BW Online Bureau, 2018).

One important element in understanding the Indian workforce is to comprehend the distinct legal and historical characteristics of its trade unions. The formation and regulation of trade unions in India is governed by the colonial Trade Unions Act, 1926 which has extremely easy norms for formation of a trade union (Shyam Sundar, 2008). The evolution of trade unions in India is linked to their role in the freedom struggle and consequent strong linkages with political parties. Even ostensibly, right-wing parties in India have affiliated trade unions. As on date there are about 12 Central Trade Union Organizations (CTUOs) in India subscribing to varying ideologies (ILO website accessed on December 6, 2019). Because of the deep politicization of unions and the erstwhile socialist nature of Indian economy, the state also frequently mediated between unions and firms (Lansing & Kuruvilla, 1987). Moreover, postliberalization, the perceived attitude of the state has gradually changed from being prounion to procapital (Frenkel & Kuruvilla, 2002). Summarizing, the uniqueness of the trade union ecosystem in India lies in the multiplicity of trade unions; the close links between trade unions and political parties and the change in attitudes toward unions (Shyam Sundar, 2008).

Despite the rich tradition of inquiry into the trade unionism in Indian context (Bhattacherjee, 2001; D'Souza, 2010; Noronha & D'Cruz, 2009; Sapkal & Shyam Sundar, 2017), there have been few studies on the impact of level of unionization on firm productivity. Gupta (2011) has inquired into the wages, unions, and labor productivity of the cotton mills of India using firm-level data from major textile producing regions of India in the early 20th century. The article identified a strong and positive link between wages and productivity and suggested that unions help improve productivity by increasing worker wages. This is contrary to popular opinion that unions resist increased work intensity. Based on a survey of manufacturing firms in five Indian states, Singh, Das, Abhishek, and Kukreja (2019) identified the magnitude of profits and existence of protective labor legislations to be positively linked to presence of unions.

The few studies that have inquired into the productivity are quite dated and have also focused on specific sectors and firms (see Bhattacharjee, 1987). We propose to fill this empirical vacuum by estimating the productivity effects of trade unions across regions and sectors. Our study is especially important given the prevalence of antiunion attitudes post economic liberalization of India in 1991 and the perception that unionization reduces the ease of doing business, a current priority area for the Indian central government.

4 METHODS

4.1 Sample

Our initial sample consisted of the top 200 listed firms based on market capitalization on the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE). The BSE is the premier stock market exchange of India with an estimated total market capitalization of around $2.2 trillion. We have chosen the top listed firms for our data collection as they must follow stringent corporate governance norms and are likely to have pan-India operations. Besides Securities and Exchanges Board of India (SEBI) has come up with a series of notifications and change in rules which mandates the listed firms to make certain disclosures—in this case disclosures about the characteristics of the workforce including percentage unionization. We collected information for these firms from their latest annual reports and audited financial statements including the year of incorporation, industry to which they belong, the size of the firm, the total fixed assets, the total number of employees and percentage unionization. The financial data was in INR millions. The total income and market capitalization of the selected firms, in dollar terms, was around $770 billion and $1.7 trillion, respectively (at an exchange rate of 72 per dollar) in FY 2018–2019, ending on March 31, 2019. The combined employee strength of all the selected firms was 5.7 million including both temporary and permanent employees out of which 1.4 million, around 24.4% of the sample were unionized. The final data suggested that the initial sample was representative of the universe of Indian listed firms and accounted for the bulk of market capitalization of all listed firms.

4.2 Analytical technique

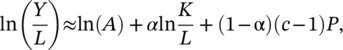

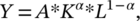

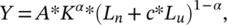

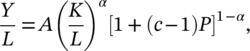

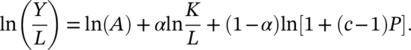

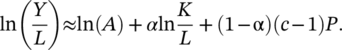

Standing on the shoulders of giants, and to ensure consistency, we have used the modified Cobb–Douglas production estimation (Brown & Medoff, 1978) to estimate the impact of degree of unionization on firm productivity. Despite its limitations the Cobb–Douglas production function has been widely used to estimate the union productivity effects. We argue that despite being dated this production function is quite robust for firm-level estimates and it offers us the much-needed leeway to increase the empirical complexity and go beyond the union presence absence dichotomy.

The Cobb–Douglas function that forms the theoretical bedrock of this study analyses the output of the firm from their dominant industrial activity and conceptualizes output as arising from a combination of labor and capital. Hence, firm sales have been used as the output variable which is in line with most research in the field of economics and finance (see Boubakri, Cosset, & Guedhami, 2005; Helpman, Melitz, & Yeaple, 2004). Moreover, for our analysis we have taken the sales per employee—which would be an adequate representation of the productivity rather than sales figures alone—the sales figure would be a static figure while the sales per employee would be a dynamic/flow type of indicator and more appropriate. We do not measure output in terms of firm's total income because of its multifaceted nature, which includes revenue from licenses, tax refunds or sale of assets. Consequently, it is susceptible to major fluctuations and external events not within organizational control, and hence suitable conclusions about output of the firm may not be inferred. As sales is the output variable, any firm for which we did not get the total sales information was removed from our initial sample of 200 firms. This resulted in the removal of 34 firms.

At the second level, we removed all the firms operating in the financial sector. The decision to drop firms belonging to the financial sector was taken in line with the recommendations of Herring and Santomero (1995). The article suggested that low real assets differentiates the financial sector from other sectors. The low capital base of financial firms may limit the applicability of the Cobb–Douglas function. In our sample also, the financial sector was qualitatively different from other sectors with the sales to total income ratio for this sector being less than 50%, compared to 96% for the rest of the firms. The low ratio of sales to total income also limits the usability of the Cobb–Douglas function as it analyses the output of firms from their dominant industrial activity. After removing financial firms and firms with no sales data, our sample consisted of 133 firms.

(1)

(1)4.3 Measures and methodology

The firms' output has been measured using the sales reported by the firms in their financial statement of 2018–2019 as well as profit after tax (PAT). To validate the appropriateness of sales as a measure of output attributable, we measured the ratio of sales to firms' total income for our sample and found this ratio to be above 95%. To verify if sales was a good proxy of production, we calculated the value of total change in stock of inventory for all firms and measured the ratio of total change in stock of inventory to firms' total sales. The ratio was less than 1%. This analysis indicated that sales was the primary source of income for the firms and most of the sales was attributable to production in the current financial year. Hence, the use of sales as output measure for the Cobb–Douglas function seems justified. Further our interest is in productivity and consequently we have computed sales per employee measure. Additionally, we have computed PAT per employee as an alternate measure of productivity to enhance the rigor of our analysis. To measure the capital involved in the sales, net fixed assets was used as it measures the capital involved directly with the production process. The labor component of a firm includes permanent as well as temporary workers. Hence, to measure the labor component of a firm, data was collected on the total number of permanent employees and contractual employees in each firm and added. The total employee strength was used as unionization rights are applicable for both permanent and temporary workers in India (Padhi, 2014). The union percentage was taken from the annual reports as reported by the firms. The coefficients of the modified Cobb–Douglas function were estimated through stepwise regression analysis. Additionally, we have used age of the firm (in years) as the control variable. Age of the firm was measured as the difference between the year for which data was collected (2019) and the year of incorporation. Age of the firm has been used as the control variable because older firms have greater opportunities to accumulate fixed assets. The rate of unionization has also been found to be positively correlated with firm age (Brown & Medoff, 2003), which may be due to the greater degree of unionization in traditional sectors of the economy. We also have measured the sector of the firms through a dummy variable (public = 0, private = 1)—owing to the earlier evidences of relationship between unionization and productivity depending on the sector to which the firm belongs (Ferner & Quintola, 2002; Sen, 1997; Sodhi, 2013).

5 FINDINGS

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics (SDs in parenthesis) in the diagonal along with the correlation matrix for the variables. Natural logarithm of sales per employee was extremely significantly correlated with both natural logarithm of assets per employee and the union percentage.

| Sales per employee (ln) | Age | Assets per employee (ln) | Union percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales per employee (ln) | 2.19 (0.878) | |||

| Age | −0.050 | 57.15 (23.106) | ||

| Assets per employee (ln) | .416a | −.241b | 1.253 (1.197) | |

| Union percentage | .415a | 0.008 | 0.107 | 43.98 (35.38) |

- a Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed).

- b Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed).

The coefficients of the Cobb–Douglas equation were estimated using stepwise linear regression technique. The natural logarithm of net fixed assets per employee was significantly and positively related with the natural logarithm of sales per employee (R-square: 17.3% and adjusted R-square: 16.4%). The variable of concern, that is, percentage of unionization was found to be positively and significantly related to the dependent variable with a t-value of 4.211 and corresponding p-value less than .01 (significant at the 1% level). The second model with both natural logarithm of assets per employee and degree of unionization as independent variables explained significant variation in the dependent variable (R-square: 31.2%; adjusted R-square: 29.6% and F-value of the changes in the expanded model being significant at the 1% level, that is, F-value <.01).

To check for sector-specific variability, we added a dummy variable sector that indicated whether the firm belonged to the public sector (sector = 0) or private sector (sector = 1). Stepwise regression indicated that natural logarithm of sales per employee was negatively correlated with private ownership, which was surprising and counterintuitive as the dominant notion is that privatization usher's efficiency and increase in productivity. Table 2 presents the unstandardized coefficients along with the t-values and the corresponding significance levels with natural logarithm of sales per employee as dependent variable; natural logarithm of assets per employee and degree of unionization as independent variables; age as control variable and ownership as dummy variable.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Statistic (p-value) | Coefficient | t-Statistic (p-value) | Coefficient | t-Statistic (p-value) | |

| Constant | 1.814 | 14.841 (.000) | 1.442 | 10.101 (.000) | 2.046 | 6.137 (.0000) |

| Assets per employee (ln) | 0.305 | 4.316 (.000) | 0.276 | 4.225 (.000) | 0.214 | 2.997 (.000) |

| Union percentage | 0.009 | 4.211 (.000) | 0.008 | 3.197 (.002) | ||

| Sector (dummy) | −0.523 | −1.999 (.049) | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.164 | 0.296 | 0.319 | |||

| F-statistic for model | 18.627 | 19.933 | 15.073 | |||

| Change in R2 | 17.737 (.000) | 3.995 (.049) | ||||

To add rigor to our findings, the Cobb–Douglas function was re-estimated with the natural logarithm of PAT per employee as the dependent variable—the premise being that ultimate aim of all firm activities is to generate profits. Stepwise regressions indicated that degree of unionization had an incremental and significant positive relationship with the dependent variable, after considering the effect of natural logarithm of net fixed assets per employee. The natural logarithm of assets per employee was found to be significant at 0.01 level with adjusted R-squared value of 0.109 (t-value of 3.434, and corresponding p-value of 0.001 with unstandardized coefficient of 0.307). In the second step not only was natural logarithm of assets per employee extremely significant but the main variable of interest—degree of unionization—was also found to be moderately significant (p-value of 0.088, t-value of 1.723 and unstandardized coefficient of 0.005) with adjusted R-square value of 0.129 indicating that the degree of unionization does impact the natural logarithm of PAT per employee. Table 3 presents the unstandardized coefficients along with the t-values and the corresponding significance levels with natural logarithm of PAT per employee as dependent variable, natural logarithm of assets per employee and degree of unionization as independent variables and age as a control variable.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | t-Statistic (p-value) | Coefficient | t-Statistic (p-value) | |

| Constant | −0.353 | −2.309 (.023) | −0.565 | −2.899 (.005) |

| Assets per employee (ln) | 0.307 | 3.434 (.001) | 0.295 | 3.322 (.001) |

| Union percentage | 0.005 | 1.723 (.088) | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.109 | 0.129 | ||

| F-statistic for model | 11.795 | 7.516 | ||

6 DISCUSSION

We had embarked on our quest to understand the effect of the degree of unionization on the productivity of the firm in the context of India especially since India is playing a pivotal role in the world economy. Besides scholars contend that in the backdrop of globalization the productivity effects of degree of unionization needs a re-examination in different economic contexts (Doucouliagos et al., 2017; Freeman, 2005). India is a unique setting not only because of its pivotal role in the world economy but also because it is a major transition economy and has surplus labor. In the context of India availability of relevant information has often been a major impediment in carrying out proper econometric assessment which we have overcome in this research (Das, 2000). Methodologically this research may be considered as a pioneer in India regarding its use of secondary data (published annual reports of BSE 200 firms) in line with the recommendations of Doucouliagos, Freeman, Laroche, and Stanley (2018). It is to be noted that the firms started reporting rates of unionization only around the year 2017, subsequent to the notification by SEBI making it a mandatory disclosure for BSE 500 firms (PTI, 2015). We measured the productivity of the firm using the rubric of sales per employee as well as PAT per employee to add rigor to our analysis. Our empirical results add to the substantial research on the degree of unionization on firm productivity (Freeman, 2005). Besides the positive effect of unions on firm productivity is in sync with most recent meta-analyses (Doucouliagos et al., 2017). The uniqueness of the study lies in testing the relationship of degree of unionization and firm productivity in India, a major economy undergoing transition.

Post liberalization, successive Indian regimes have been focusing on competitiveness and labor flexibility in a bid to attract foreign direct investment and keep the growth momentum. With management's extreme focus on competition and efficiency, trade unions probably act as channels of voice as theorized in the “collective voice” perspective (Freeman & Medoff, 1984). This view is supported by union revitalization strand of research, such as Partnership Unionism ((Badigannavar & Kelly, 2011; Balasubramanian & Sarkar, 2017; Heery, 2002). Thus, we would like to posit that trade unions seem to be having a positive impact in countries transitioning toward becoming market-led economies by acting as conduits for employee voice, making them a necessary evil for the firms. These results assume significance given the global decline of trade unions, with India being no exception (Balasubramanian, 2015).

Despite being in consonance with the overall direction of research in this field (Freeman, 2005; Freeman et al., 2017; Williamson, 1985), our results are counterintuitive to the popular understanding that unionization negatively impacts productivity of firms. Our hypothesis is that the positive role of unions is best explained by social exchange theory that leads to synergistic relations between unions and management in India for historical reasons. Similar arguments have been made in the Japanese context by Morikawa (2010).

Social exchange theory is predicated on the assumption that humans, individually and collectively, are rational agents and hence try to build long-term, mutually beneficially relationships by positively reciprocating rewarding reactions from other entities (Emerson, 1976). In India, unions traditionally have high social acceptance because of their role in the freedom struggle and, as per social exchange theory, this acceptance creates unspecified obligations (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005) on unions to pursue follow synergistic courses of action, which are not detrimental to the overall public good, in collaboration with employers in order to preserve their social capital. Social exchange theory has been used to explain positive relationships between perceived union support and members' commitment toward unions (Sinclair & Tetrick, 1995) and employee voice and organizational commitment (Farndale, Van Ruiten, Kelliher, & Hope-Hailey, 2011).

Besides social exchange theory, relationships between political parties and unions and underlying ideologies of unions can also contribute to the positive relationship between unionization and firm productivity. In India, all political parties have labor/union wings and political parties, especially those in power, must convince the voting populace of their ability to attract investment. Thus, unions are pressurized by their political bosses to adopt a cooperative rather than adversarial approach in their dealings with employers. Ideologically also most unions in India subscribe to the philosophy that labor and capital are mutually dependent on each other and hence need to pursue mutually beneficial course of action.

Recent research in China have identified negative impact of degree of unionization on productivity (Yang & Tsou, 2018). Despite similarity between China and India on multiple parameters such as overall population; presence of large state-owned enterprises and comparatively recent changes in economic policy, we have found evidence for positive association between firm productivity (measured as sales per employee and PAT per employee) and degree of unionization in the context of India which is intriguing and counterintuitive. We contend that this needs greater investigation. Most interestingly, the positive effect of degree of unionization on sales was more pronounced for public sector firms, that is, firms where the government of India is the promoter and largest shareholder than for private sector firms (Afonso, Schuknecht, & Tanzi, 2015). There has been a lacunae of research on the relationship between degree of unionization and profitability (Kochan & Kimball, 2019) with comparatively recent studies (e.g., Hirsch, 2007) identifying negative relationships. Our research helps fill this vacuum and also supports positive effect of unionization on firms' profitability.

Kochan and Kimball (2019) suggest that unions play a key role in ensuring sustainable increases in productivity as their presence affirms the social contract between employers and employees to improve firm-level productivity and distribute the productivity gains justly. However, despite the central role accorded by some scholars in ensuring the continued relevance of a mutually beneficial social contract between employers and employees, the decline in union membership has probably resulted in a decline in research interest regarding the effect of unionization on various work-related variables like productivity, wages and unions. This indifference toward analyzing the effects of unions is also reflected in India-based studies where, despite the uniqueness of its cultural settings and the impassioned debates about the positives and negatives of government control over the economy, there have been almost no studies on the link between unions and productivity. This study establishes that for large firms with some degree of unionization, increased unionization was correlated with increased sales per employee in the recent past, that is, 2018–2019.

7 IMPLICATIONS, LIMITATIONS, AND FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Our findings have significant theoretical and practical implications in determining the direction of trade union research and praxis in the context of any transitional economy especially India and South Asia. Our results also inform policy formulation with respect to unionization. In the context of India, we have found empirical evidence for significant positive association of degree of unionization on firm productivity and profitability. This goes a long way in helping the cause of unionization which has often faced flak for their negative image. The positive role of unions is, prima facie, contrary to the perception that stringent labor regulations are major roadblocks for firm flexibility and productivity—consequently, we argue for a nuanced approach toward issues of labor flexibility and reforms in labor laws. Our empirical evidence can shatter some of the prevalent myths and negative stereotypes associated with respect to the impact of trade unions on firms' productivity and profitability. Our research provides some empirical grounding for reorienting the direction of policy formulation from increasing labor flexibility to building institutions that can coordinate between employees and employers and function as channels for employees' collective voice. Methodologically, the study adds credibility to the use of Cobb–Douglas function in measuring output in Indian firms. The study also adds to the rich literature of studies making use of secondary sources of information within the field of HR, more specifically Industrial Relations. We also stake humble claims for being among the few studies that have estimated the effect of degree of unionization on firm productivity in the context of a transition economy specifically India.

- Sales for this year reflects production of this year. This is partially verified by demonstrating that existing inventory did not contribute much to production.

- Sales data is not highly volatile across years. Volatility would reduce generalizability across years.

-

Labor quality is uniform across firms

- Difficult to measure labor quality as education quality is uneven

- Quality of assets is uniform across firms.

We could not verify these assumptions because of lack of proper data. Due to the secondary and cross-sectional nature of the study, it is difficult to identify the mechanisms through which unions contributed to firms' productivity or to specifically point out the causality. More in-depth studies need to be conducted to identify the mechanisms through which unions affect productivity.

Meta-analysis of union productivity effect has found a significant temporal variation in to productivity estimates (Doucouliagos & Laroche, 2003) and can be explored in future longitudinal studies that capture temporal impact of the effect of degree of unionization on the firm productivity and firm profitability. Similarly, the productivity effect of unions also seems to vary with the industries which again in our research we have not captured beyond the public/private sector dichotomy. We further invite scholars to test the firm productivity and unionization relationship using the Cobb–Douglas Function for different industries/sectors and preferably use a panel data for more conclusive and robust inferences. We invite scholars to replicate our results on the union effects of productivity and profitability in the context of transitional economies especially India. We further invite scholars to carry out the Cobb–Douglas production function estimate on a longitudinal data for the firms with all the 1,000 listed firms of BSE since it is now mandatory for these listed firms to comply with the rigorous norms of reporting for corporate governance. Expanding the data set to 1,000 firms is also likely to provide the variation in industries which can also further be inquired into. In the current study the output has been operationalized as the total sales of the firm and the PAT. We invite scholars to assess and estimate the Cobb–Douglas function for any other measure of output as well. This would not only add rigor to the empirical evidence but also reduce the ambiguity of results One interesting area of future research is to ascertain the degree to which the positive effect of unions is attributable to India-specific reasons rather than to universal reasons.

8 CONCLUSION

Despite the need for research to assess the economic impact of degree of unionization on the firms in different economic and social contexts (Doucouliagos et al., 2018), there has been a dearth of recent studies. The current study fills this gap. To the best of our knowledge ours is a unique study in the Indian context to assess the firm-level productivity impact of degree of unionization. For an economy undergoing transition, like India, we have estimated positive effect of degree of unionization on the firm productivity. The second major counterintuitive and contrary result of our research is that, controlling for capital per employee, productivity (as measured as sales per employee and PAT per employee) in private sector firms is low as compared to their public sector counterparts—which is a surprise as the current dominant understanding is that privatization ushers in efficiency. Although not the focus of this research, the degree of unionization also seemed to have a positive effect on the profitability of the firms. This exploratory investigation has opened up the debate on the effect of degree of unionization on firm productivity. We invite scholars to assess the same using more rigorous empirics to find a conclusive answer.

ENDNOTE

Appendix A.:

DERIVATION OF MODIFIED FORM OF COBB–DOUGLAS FUNCTION

(A1)

(A1) (A2)

(A2) (A3)

(A3) (A4)

(A4) (A5)

(A5)Biographies

Dr. Girish Balasubramanian is Fellow of Management from XLRI Jamshedpur specialized in Human Resource Management Area. He has worked with reputed multinational firms from operations and energy sectors. His research interests include Diversity Management & Leadership in Public Administration, Industrial Relations and Strategy, Performance Management.

Dr. Sanket Sunand Dash is a faculty in the area of Organizational Behaviour & Human Resource Management (OB&HRM) at Indian Institute of Management Rohtak. He has completed Fellow Program in Management (FPM) from Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. He worked as a senior analyst with Deloitte US India for four years before joining the FPM program in IIM Ahmedabad. Before joining IIM Rohtak, he was a faculty at Xavier School of Human Resources (XAHR), Xavier University Bhubaneswar. He has diverse research interests including proactive work behaviors, perceptions of performance management systems, unionization and its effects and knowledge management. He has published papers in international journals on various research topics.