Migrants, work, and sustenance in the coalfield of Raniganj

Abstract

Coal mining began in the Raniganj Coalfield of India in the second half of the 18th century. Growth of economy based on coal production, consequently gave rise to a number of mining towns and steel industries in the region. Expansion of settlements in the coal region was followed by waves of migration among workers. The settlement of Raniganj located in the state of West Bengal initially witnessed migration of marginalized castes and tribal population from its neighboring districts. The trend of intrastate migration changed, when workers migrated and settled down from other states of India such as Jharkhand, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh. Mine authority and workers face challenges of maintenance of safe work environment in the coal mines. This research traces the trend of migration among workers in the coalfield of Raniganj. The research also focuses on the risks of work associated with coal mining and the initiatives taken up for provision of healthcare, protection of workers, and sustenance.

1 INTRODUCTION

Migration for employment, often results from the expectation of higher wage and availability of alternatives to an economic activity. Ravenstein (1889) asserts that migration is the outcome of aspirations of higher wage rates and is often short distance (Ravenstein, 1889). The models of Harris and Todaro (1970) assumed migration as a consequence of the expectation of higher wage rates than the actual wage differentials (Sengupta & Ghosal, 2011). In the mineral-rich areas of India, majority of the migrants are engaged as informal workers. Literature divulges that the Indian coal mining industry in its years of inception had been plagued by unplanned mining, inadequacy of mechanization, shortfall of wagons for transport of coal at the mine pits, and exploitation of laborers. Such shortcomings associated with the economic activity of coal mining have had implications on the migrants and residents living near collieries (Mourya & Chakraborty, 2012). Extraction of coal from seams is a lucrative economic practice because it generates income for artisanal workers. However, artisanal workers while extracting coal do not take into consideration their vulnerability to health risks and hazards.

The coalfield acts as a source of income for both mine workers and the ancillary industries located close to the mines. Informal miners find easier access to coal seams at the open cast mines because such mines are difficult to keep under vigilance due to their extensive sprawl on the surface of the earth. Informalization of work in the mines has gone hand-in-hand with formal extraction of coal since the inception of the mining industry. The informal engagement of laborers in coal mining industry remained obscure unlike other sectors of economy; only recently, as employment rate has gone down and menaces of coal hazards have risen, the trend of informal mining in the area has become prominent.

Debates on “Political Economies of Extractive Industries” (Bebbington, Bornschlegl, & Johnson, 2013), studies on oil extraction industry of Kazakhstan (Jager, 2014), China's coal mining industry (Cote, 2015), metal mining industry in Zambia (Frederiksen, 2019), and other researches make the point that, regions with extractive industries receive unemployed migrants. The mineral-rich regions of India, with location of extractive industries are characterized by prominent migration trends. The mineral endowed Chota Nagpur plateau in eastern India, has witnessed population growth in some of its industrial cities like Jamshedpur, Durgapur, Asansol, Raniganj, owing to the migration of workers in mining and manufacturing industries. Coal mining as an extractive industry attracts migrants because of easy access to coal and income generation, particularly at the open cast pits. In the extractive industries, migrant workers toil in unsafe work environment under loosely governed terms of work. An interesting question that comes up is—why over the years the towns in the Raniganj Coalfield have recorded a lowering rate of migrant population despite holding extractive industries that are largely worked by migrant laborers. The research strives to understand the significance of coal mining as a livelihood for the workers in the region and also explores the risks of accidents and health implications for the miners.

The research article covers two broad sections, the first section looks into the evolving trend of migration among workers—the distinct phases of changes in migration in terms of reasons behind migration and changing composition of labor class. Although the major pull factor for migration in the Raniganj coal belt remains economic, that is earning a livelihood; there has been a slight shift in the sector of economy or major industry that attracts the largest number of workers in the region. The first section of the research article explores this transition. The study of literature on migration and work conditions in the Raniganj Coalfield, analysis of migration data of Census of India for the years 1971, 1981, 1991, and 2001, brings out the trend of migration in the study area. Primary survey and interactions with mine workers during several field visits between the years 2011 and 2017 have helped to understand the reasons behind the changing proportion of migrants among mine and industrial workers, in addition to the migrants' choice of neighborhood in the destination.

Plans have been drawn for the expansion of production capacity of the mines to meet the increased demand for coal. This has given rise to issues of relocation of settled population, homesteads, and shifting of cultivated croplands, diversion of infrastructural set-up such as railway tracks and pipelines. The second section of the article examines the nature of occupational hazards and the risks that laborers at the collieries face, while working under the mining authority as well as engaging in informal mining. Corporate social responsibility and risk management by mining companies for protection and resilience of settlements against disasters is essential. However, there are layers of political, economic, and social barriers in the formulation of plans and their successful implementation; this in itself paves out the realm for a separate, larger theme of enquiry and research not addressed in detail in this article. The research attempts to acquire an overview of the challenges faced by local authorities while planning for healthcare and protection schemes in the study area.

2 SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY AREA

The first instances of coal mining in India can be traced to Raniganj in the state of West Bengal (Banerjee, 2011). The study area constituted by the Raniganj Coalfield (RCF) in Paschim Barddhaman district of Bengal is not only the oldest region where coal mining is practiced, but it is also the second most expansive in India (after Jharia Coalfield in Jharkhand state) in terms of reserve (Government of India, 2016b). The study area is located in a region that has experienced the development of an urban-industrial corridor subsequent to the growth and expansion of mining industry and houses more than 25,00,000 people (Government of India, 2011b).

The Eastern Coalfields Limited (ECL) was formed as a subsidiary of Coal India Limited (CIL) in 1973 (after the nationalization of coal mines). ECL has 117 coal mines operating under its authority in the Raniganj Coalfield, some of which are the oldest and deepest underground mines of India. Before the advent of coal in 1774, Raniganj was deeply seated in the forested land of “Jangal Mahal” (Koshal, 2006). In mid-20th century, the landscape was transformed into an industrial and mining zone after acquisition of land and establishment of large-scale manufacturing industries. By 1960s, the options for transporting coal from the collieries improved with the expansion of rail network (Prasad, 1986). A ropeway grid started functioning by 1956 (Kumar, 1976) and further aided coal carriage from collieries to haulage points at railway stations, iron and steel plants, and wagon manufacturing units.

3 MIGRATION OF WORKERS IN THE RANIGANJ COALFIELD

Mineral endowed regions of India have witnessed the growth of allied industries like thermal power generating plants, iron and steel industries, ferro-alloy plants, cement industries, which in turn have shaped several urban-economic hubs such as Jamshedpur-Bokaro, Asansol-Durgapur, Raipur-Bhilai to name a few.

Coal mining began in the late 18th century and the area consequently grew into an industrial tract. The urban-industrial corridor of Asansol-Durgapur is located in the Raniganj Coalfield. Asansol was established as a Railway Division in 1925 when rail track of the Eastern Railway section was extended from Howrah to Raniganj. There was higher demand for coal when steam locomotives started operating and provided impetus to the growth of coal mining (Prasad, 1986). The largest land owner in the Raniganj coal belt—ECL has under its upkeep an area studded with collieries that sprawl across 443.50 km2 (Gupta, Dutta, & Basu, 2018). The coal industry employs more than 6,00,000 workers (Mandal & Sengupta, 2000). Collieries and the mining towns in the region initially recorded migration of workers from the districts located close to the Raniganj coal belt within the state of West Bengal. Later, people also migrated from the neighboring states of Bengal, namely Jharkhand, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

3.1 Socioeconomic attributes of labor migration in the 19th century

Migration changes the composition of workforce in mining areas. Re-composition of working class due to migration is a common demographic attribute of mining regions (Overview of Coal Mining in India, 2011). Seasonal, short-term migration of circular type by tribal castes was dominant in the initial years of coal mining in Raniganj (the last few decades of 18th century and early years of 19th century). Most migrants settled down as agricultural tenants in nearby land and practiced agriculture, while some migrants went back to farms in rural areas, for cultivation (Irudaya Rajan, 2016). The composition of mining labor force had a majority proportion of peasants and artisan groups belonging to lower castes or tribal societies (most of them Santhals and Bauris) who migrated to Bengal from districts in Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh (Das Gupta, 1985).

The region did not record much change in terms of urban development in the early 19th century. On account of limited scope of absorption in sectors other than mining, migrants came in very small numbers from rural to urban areas. Migration among mine laborers was chiefly from the agriculture to the mining sector. Although agriculture provided the workers with slightly higher average monthly wages compared to coal mining, in case of cultivation of crops the scope of work was seasonal in nature. This doubled with bad harvest or famine-like situation forced workers to migrate to areas under coal mining (Hunter, 2005).

By the end of 19th century, 20% of the district's population had been supported by migrants employed in industry, commerce, and services of various kinds. People belonging to the aboriginal tribes were known for their endurance; Bauris worked with picks whereas the Santhals worked with crowbars (Hunter, 2005). The major share of the mining labor force was constituted by tribal and rural communities having connectivity to market towns like Raniganj. Most workers migrated to agricultural land for a short-term during sowing or harvest seasons. In 1919 underground mine workers used to work without any “set hours” or “shift of work” earning average monthly wages of rupees five and a half to six; wages increased to about rupees 24 in the later years of the century (Das Gupta, 1985).

3.2 Trend of labor migration in the 20th century

In the first few decades of 20th century, most laborers employed in the mining industry were either local or short-distance migrants from rural areas (Chatterjee, 2017). Until 1920s, wages in the coal mining industry were good, and the surplus income was mostly wasted by miners staying at grim, dingy living quarters, on excess liquor (Hunter, 2005). In 1930s, large groups of men and women migrated to the coalfield from rural areas after being affected by famine. The flow of migrants to the collieries was never consistent owing to slashed down wage rates. Women were excluded from working in the underground mines (Das Gupta, 1985).

There are several instances where the prominence of tribal communities working in the coal mines comes to the forefront. In the year 1943, tens of thousands of laborers including women and children from Santhal tribes were brought in to work the coal mines inundated by Damodar flood; and only after a decade, the government was obligated to take up socialistic approach for harnessing energy resources and protecting workers from hazards. The Damodar Valley Corporation undertook multipurpose project planning for assurance of safety of the workers and local residents (Bhattacharjee, 2017). The deprived classes of people were willing to work for low wages due to the dearth of alternative sources of income.

In 1920s, women supported about a third of the total work force among miners. However, by 1950s, female workers dwindled in number and engaged in informal work at the peripheries of open cast mines or scavenged through coal stock yards or burnt coal dumps at the surface of mine pits. The number of female workers dropped progressively as mines became mechanized. The value of female labor force deprecated under the pretexts of “safety issues” and mining being a “man's job” (Chatterjee, 2017).

3.3 Migration for employment in the manufacturing industries

Iron and steel plants in the Raniganj Coalfield were established in Kulti and Burnpur in the years 1870 and 1918, respectively. The region was transformed into a node of large and medium scale manufacturing industries in the decade after Indian independence. In 1950s and 1960s, the coal country recorded an overwhelming influx of migrant workers who found employment in the industries commissioned in that era.

The industrial region of Durgapur traverses the Raniganj Coalfield for a stretch of more than 60 km from east to west in the Paschim Barddhaman district. This industrial region recorded growth in the number of migrants from the rural districts of West Bengal as well as from the neighboring states in the decade of 1950; the major reason for this migrant influx was the establishment of industries under public sector undertaking (PSU) in the town of Durgapur. Durgapur and its neighborhood recorded conspicuous waves of migration between 1960s and 1980s. Conversely, migration among industrial workers became less pronounced when new employment reached saturation point at the large manufacturing plants such as locomotive works, iron and steel units. Since 1980, industrial sickness had started spreading its grip among some of the medium-scale industries like glass factory, paper mill, and cycle factory; departments had begun termination of production which further constricted the options of employment. Although revival plans were drawn in 1997 with financial assistance from the Board of Industrial and Financial Reconstruction (BIFR) under the Sick Industrial Companies Act (SICA) and ICICI (Lahiri-Dutt, 1999), the region saw recovery of industrial performance only after the iron and steel plants were merged with the Steel Authority of India Limited (SAIL) in 2006.

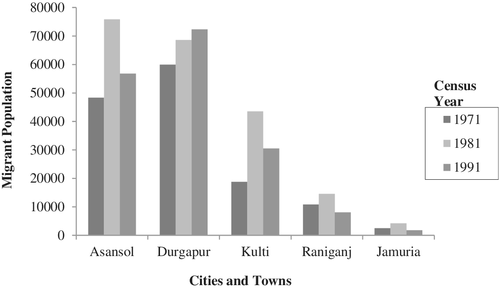

In 1970s and 1980s, migrants comprised 20–30% of the population (increasing between the years 1971 and 1981) in the urban settlements of the study area namely Asansol, Durgapur, Kulti, Raniganj, and Jamuria (Ghoshdastidar, 2011). The share of migrant population in these towns and cities dropped and varied between 12 and 17% in 1991 (see Table 1). One reason for the decline in the proportion of migrants could be the contractual nature of employment at the collieries. Engagement of artisanal workers in mineral extraction without authorization and dearth of records makes it challenging to register the proportion of migrants among workers in the extractive industry.

| In-migrants | Asansol (%) | Durgapur (%) | Kulti (%) | Raniganj (%) | Jamuria (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 20 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 |

| 1981 | 25 | 22 | 32 | 30 | 34 |

| 1991 | 13 | 17 | 12 | 13 | 12 |

- Data Source: Ghoshdastidar (2011).

Mine workers held about 13–15% of the migrant population from 1970s to 1990s, falling to 9% in 2001 (Government of India, 2001). Raniganj, Kulti, Jamuria, and Asansol (together known as Asansol Urban Area) have higher count of migrants in mining and quarrying than Durgapur. At present, people migrating to the region have a higher total in the industrial sector compared to mining and quarrying. Durgapur has higher number of migrants than the other urban areas of the region taken together (see Table 1). There is higher proportion of migrants among industrial workers (see Table 2). The proportion of migrants out of total urban population is highest in Durgapur (see Figure 1) because of higher probability of finding jobs in the numerous small and micro-scale industries and outcrops of coal located in and around Durgapur. Census data show that intrastate migration initially occurred at a slow pace, but in recent years, more people have been migrating from the districts surrounding the Raniganj coal belt (Census of India, 2001). The industrial region of Raniganj and Durgapur now has more number of migrants from districts within the state of Bengal than beyond the state border (Census of India, 2001). The migrant population resides in the Census Towns and finds work in the medium-, small- and micro-scale industries that operate as ancillary industries to the large-scale industries such as iron and steel. This elucidates a slight shift in the major cause of migration in the area—from “settling down at collieries” earlier, to being “employed in manufacturing industries” and residing in Census Towns that facilitate residents with better civic amenities and accessibility to improved infrastructure. The circumstances of employment and production at coal mines have come to change over the years. Ninteen environmentally hazardous open-cast mines provide employment to more than 12,000 people in the Raniganj coal belt. Extraction of coal from the topmost seams at OCPs has been replaced by the use of heavy machinery because it is arduous for laborers. Introduction of machinery for extraction of coal has led to employment of workers on contract-basis at lower wage rates (Lahiri-Dutt, 1999).

| Place of residence | Urban population | Migrants | Share of migrants (%) | Mine workers among migrants | Share of mine workers among migrants (%) | Industrial workers among migrants | Share of industrial workers among migrants (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asansol urban area | 10,05,942 | 25,624 | 2.55 | 2,418 | 9.44 | 4,978 | 19.43 |

| Durgapur municipal Corporation | 4,93,405 | 26,906 | 5.45 | 522 | 1.94 | 8,392 | 31.19 |

- Data Source: Census of India (2001).

Migrants in the Cities of Raniganj Coalfield, 1971, 1981 and 1991

Data Source: Ghoshdastidar (2011)

The inflow of migrants working as informal or artisanal workers continues at the mines. However, the documentation of such migrant population becomes difficult due to the lack of registration as mine laborers or factory workers at manufacturing units, household, and non-household industries (mostly following the practice of employment under contract).

3.4 Changes in the composition of migrant workers

By 1950s, the composition of migrants in the coalfields was dominated by “males from north or central India”. This recomposition of migrant population led to a decline in the proportion of local adivasis and people from lower strata of society among the mine workers (Banerjee, 2011). The so-called “peasant workers” of tribal origin gave preference to the pick and shovel over the plow, and returned to the cultivation of soil after their grim work experiences in the coal mining industry. But soon the number of working heads in farming communities in the vicinity of the coalfield started declining. With growth in the production of coal in the 1970s, agricultural workers began transiting to non-farming practices and worked as wage laborers for contractors (Lahiri-Dutt, 2018). This was encouraged by the prospects of assured earnings in the mining sector that were indeterminate in case of agricultural practice. Coal India Limited (CIL) reports indicate that, there was decrease in the strength of manpower (engaged in the extraction of coal) under ECL from the year 1996 to 2000. One of the reasons for this decrease could be mechanization of mines. With expansion of mining operations, there was also decline in employment of females in the workforce from 1994 to 2000, under the pretexts of safety issues (Saha, 2004). Thus, the female migrants in the coalfield were left with little opportunity of work (Lahiri-Dutt, 2011) and gradually resorted to collection of coal from burnt dumps through informal engagement.

Coal mining as an extractive industry is predominantly male-worker oriented. The mining industry also creates gender gaps when the nature of labor input is considered-in terms of physical exertion, lifting heavy load, and traversing critical work environs. Female mine workers are not employed directly under ECL today. This not only takes away the probability of work assurance for female migrants but also leaves them to fend for themselves and places question on the position of women as economic workers. Approaches and planning for sustainable livelihood practices could help absorb women as miners into the workforce in greater number; this would not only support them with income but also ensure safer work environment for women.

3.5 Procurement of coal: Informal and artisanal workers

The shift of people to the coalfield for working in the mines is obscure due to contractual employment. The practice of contractual employment weakens formal work commitment and turns coal mining into a lesser assured and temporary source of income. Mining has had a history of artisanal practice that is closely aligned to legalized practice of coal extraction and even in the face of victimization and ill-effects “informal mining” continues in most areas even today (Lahiri-Dutt & Macintyre, 2016). Informal sector contributes greatly to output, holding about 55% of the total gross domestic product of the country (Samaddar, 2018) and migration supports the base of informal mining, which encompasses coal extraction by small-scale and artisanal workers.

Informal mining of coal brings with it large sums of money, especially for those indulging in the sale of coal to local users for domestic and commercial purposes. Individuals involved in the informal practice of coal extraction migrate to the mining areas of Raniganj for the opportunities of income either as miners or as entrepreneurs and sometimes engage workers on contracts for coal collection (Lahiri-Dutt, 2018). Thus, there are two commonly seen ways of engagement of workers at the coal mines: first, engagement of workers under contract with informal conditions of work and casual terms of agreement and second, artisanal workers choosing to collect coal informally from abandoned mines and exposed coal surfaces. The first kind of employment leaves the laborers with no social protection, vulnerable to occupational menaces, whereas the second scenario brings upon the miners high risk of accidents that aggravate hazards.

The permanent coal mine workers have dwindled in count since 1990s and informal mining has taken the position of an industry that runs parallel to nationalized coal mining, prominently characterized by a growing division between impoverished proletariat and a small workforce (Overview of Coal Mining in India, 2011). The informal practice of coal procurement makes obtainment of the resource easy and quick (although it puts lives at stake). Rules of authorization and laws of sanction do not govern informal practice of mining. The portrayals of work conditions of migrant communities collated in the book “Rethinking Displacement: Asia Pacific Perspectives” (Ganguly-Scrase & Lahiri-Dutt, 2012) makes one reflect upon the truth that migrant laborers in the informal industry are “preferred” by contract providers because informal engagement not only helps control wage rate and prevents it from rising, but also leaves little obligation of providing protection schemes unlike permanent jobs.

Migration of transit laborers to the coal belt affects the availability, composition, and wage determinants for labor. Moreover, it modifies the physical and social circumstances under which people endeavor to gain economically because the surface configuration of mine areas change; this change in ground cover near coal pits is brought about by the method of coal extraction that is adopted (which incorporates either digging holes unscientifically or cutting the walls of coal seams or the roofs of abandoned mines).

3.5.1 The menaces of informal mining

The opportunities of income in the coalfield bring challenges of maintaining safe work environment. Informal mining is the unsanctioned acquisition or collection of coal from operational, abandoned, or closed mines leased out by government or under government possession. Similarly, pilferage includes unrightfully picking up coal from stock pile yards, coal washers, from points of coal haulage or during transshipment by rail and road; both informal mining and pilferage result into financial losses for the mining company and often give rise to accidents and injuries, mine fire break outs, death, property damage and social disturbances.

Accidents and mishaps such as mine roof collapse and fire breakouts at coal seams are common when casual, unscientific methods of coal extraction are used. These calamities could culminate into catastrophe such as land-subsidence, uncontrollable mine fire and add to air pollution and loss of life and property; it intensifies concerns of protection for laborers who toil in the shady occupation of informal mining.

Newspaper articles, while shedding light on the risks associated with informal mining, distinguish the economic activity as “a satisfactory and prospective livelihood” in the words of the committers who make a living of about 300 Indian Rupee (INR) a day (Niyogi & Chakraborty, 2016). Young and middle-aged men emerge from unlawfully dug pits near abandoned or functional coal mines and load over-flowing sacks of coal onto their bicycles and push them for 8–10 km—scenes that are common along stretches of the National Highway Number 2 (NH-2) between Barakar (near Jharkhand-West Bengal border) and Asansol. Unauthorized coal pits have been revived in the outskirts of Barabani, Jamuria, Pandabeswar and Ondal; close to 50,000 people toil to lift coal in these areas because they do not have alternate means of livelihood for supporting their families. Distribution of coal from illicit deposits runs as a parallel economy (Niyogi & Chakraborty, 2016).

Networks of horizontal tunnels are often reached after digging out vertical openings known as rat-holes and the method of coal extraction that uses such a hole is known as rat-hole mining. Collapse of mine roof in rat hole mining, jeopardizes the lives of people. Industrial forces, armed guards of mining authority, and police sometimes fail to prevent the entry of pilfers and rat-hole miners inside the unfenced premises of collieries because the vast sprawl of mines is difficult to keep under strict surveillance. Thus, it becomes impossible to keep intruders at bay, who despite knowing about the risks that lurk upon them, are in constant search of ways that make procurement of coal easy.

4 RISKS OF COAL MINING AND PROTECTION SCHEMES FOR WORKERS

Best practice mining is the method of mining that engages precautionary measures and incorporates procedures which are least harmful to the environment and humans. In the late 1990s, environmental management plans for the Raniganj Coalfield, fell short at addressing issues of safety and concern for health of workers and protection of local environment. Tree plantation at over-burden dumps for afforestation and construction of residential units for employees were the only facilities provided by the mining company two decades ago.

4.1 Coal mining and associated risks

The coal mines are hazardous, insecure, and uncomfortable as place of work. Migration of workers to earn a livelihood in such hazard-prone landscape changes the demographic attributes that constitute the size of population in the area. It also gives rise to a number of health implications and complexities in providing protection. Workers toil in smoky chambers that lack ventilation and have insufficient lighting conditions—this makes it difficult to procure coal, and the dearth of air circulation inside mine shafts endangers health of workers and paves the way to ailments. In the initial years of mining in Raniganj, work condition and its implications on the health of laborers had not been subjects of worry for the employers, neither was there planning for environmental protection.

There are several historical accounts of migrants working under dire conditions at coal mines. Prior to Indian independence, there have been instances where tribal population moved into the coalfields to forcibly work at mines. Mine workers had to put up in crowded makeshift huts known as “dhowrahs,” constructed close to the mines but far away from markets. There was scarcity of amenities like water supply, sanitation, medical care in these huts; but they were constructed to escape the dingy housing provided by the mining authority till the 1940s (Das Gupta, 1985). The Coal Mines Regulations framed by a Committee under the Director General of Mines Safety in 1959 included guidelines and standards for lighting arrangements and ventilation in mines (Ghosh, 1974). The Mines Rules 1955 had specified that at least 2 L of drinking water should be ensured for every person working in the mines (Government of India, 1955); yet issues of water supply remained unresolved till 1967 (Ghosh, 1974). There was absence of organized, collective protest among the colliery workers for demand of betterment of the state of affairs; and the deplorable plight of working and living conditions continued till the nationalization of coal mines in 1973 (Banerjee, 2011).

4.2 Occupational hazards at the mines

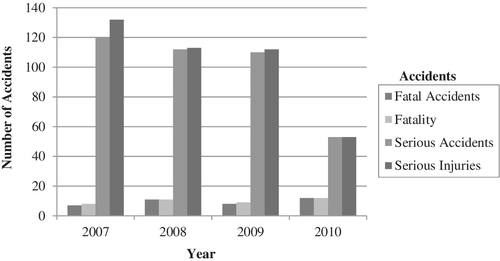

Work safety in the Indian coal mines is a vital issue that has been addressed only in the last few decades. Mining area under ECL has had more number of accidents than the remaining mining subsidiaries of Coal India Limited (CIL), which have lesser areal coverage and operate on a smaller scale of production. Workers at underground mines (UGM) are prone to fatal accidents (see Figure 2). Roof collapse, fall of side wall, explosions, gaseous expulsion are common during excavation and mine blasts. Other mishaps include inundation of mine inclines and pits, collapse of coal tubs, workers being hit by vehicles, collision of vehicles such as dumpers, and workers falling from a significant height along the strips of open cast pits. The maximum number of accidents at underground mines (see Table 3) is caused by mine roof collapse, followed by disruptions during haulage and fall of person. At open cast mines collision of dumpers is responsible for the highest percentage of accidents (Mandal & Sengupta, 2000). There is limited use of protection gear among colliery workers. Helmets with lamps, boots, and harness are used in underground mines; breathing masks, protection gloves are not part of the regular uniform of mine workers. As reported by the newspaper “The Telegraph” on August 25, 2018—introduction of monorail for movement of miners in underground pits, such as the one inaugurated in 2018 at Moonidih colliery in Dhanbad under Bharat Coking Coal Limited (BCCL) ushers in hopes of convenience, and improvement of safety and protection of workers (“Monorail fillip for colliery,” 2018). The number of accidents at mine sites has reduced over the years (see Table 3) because of improvement in work conditions. However, lack of precautionary measures and the absence of scientific method of coal extraction by informal miners keep the record of accidents high at the sites of unauthorized coal pits; and these occurrences mostly go unregistered due to their unlicensed nature of practice.

Accidents at Mines of Eastern Coalfields Limited, 2007 to 2010

Data Source: Government of India (2011a)

| ECL | UG mine | OC mine | Surface | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatal accidents (number) | 159 | 21 | 37 | 217 |

| Accidents (number per million ton production) | 1.297 | 0.203 | 0.166 | 0.970 |

| Accidents (number per million manshifts) | 0.559 | 0.451 | 0.112 | 0.667 |

- Data Source: Mandal and Sengupta (2000), pp. 7–8.

Mine fires from burning coal seams, land-subsidence triggered by extraction of coal at open cast mines and coal mining from abandoned mines put the lives of laborers and local communities at stake. Mine fires leave the ground unstable and raise the risk of accidents and casualties among workers and local residents. This necessitates relocation of the inhabitants residing in the localities that surround the coal mines and the use of caution and protective gears by mine laborers (Melody & Johnston, 2015). The environmental conditions prevalent in the collieries of Raniganj are cause of concern because the concentration of particulate matter persists above the World Health Organization standard of 50 μg/m3 (Government of India, 2016a). The multitudes of people residing and working in the region are vulnerable to disasters and therefore are in need of legal measures and adequate approaches for building sustainable and safe economy.

4.3 Challenges of healthcare and protection for mine workers

It is difficult for authorities-in-charge or the government to relocate displaced families through resettlement plans, owing to complications of economic alternatives and social bindings. Compensation often does not turn-out as planned or proposed under rehabilitation schemes or environmental management plans. When mining operations commence the villagers displaced from land during reclamation of agricultural land holdings, either claim absorption into the workforce with permanent jobs or pose for their share in infrastructural investment (Overview of Coal Mining in India, 2011). The fulfillment of such demands is either delayed, or difficult to execute. Failure to migrate out of the region for pursuing economic activities elsewhere or return to agriculture, forces villagers to resort to coal collection illegitimately for easy and quick income. Some find jobs in the medium and small-scale industries of the region, namely sponge iron, brick factories, refractories, and others. Laborers engaged in informal mining make a home out of shanties that collectively grow into squatters. Informal miners also live in slums that lack sanitation and water and give rise to issues of scarce social security and maintenance of safe environment. Some migrant laborers also settle in the Census Towns located close to the collieries.

Health issues loom large in the coalfield for those who migrate and work in the mines. Health of workers affects their performance; frailty comes in the way of production in tons per day and has negative consequences on the hours of contribution at the mines.

Dust and fine coal particles released in the air give way to chronic respiratory troubles (Overview of Coal Mining in India, 2011) for laborers working in open cast and underground pits. Vibration of drillers, dumpers, dozers, shovels, loaders affect hearing capacity of employees at mine sites (National Institute of Miners' Health, 2011); use of ear-muffs is barely seen at the coal mines. Adoption of protective measures like gloves for protection of skin, use of masks and dust respirators should be marked “essential” during work hours. The use of safety helmet and rubber boots as well as earmuffs for protection from noise is of utmost importance at the open cast mines.

Routine health check-up, medication, and facilitation of housing in the form of well ventilated living quarters with clean and sufficient supply of water have been introduced for the mine workers. Provision of housing for workers who cannot be formally absorbed in the workforce is a challenge, more so when workers engage in unsupervised, informal mining which is unsafe for humans and the environment.

Primary healthcare centers (PHCs) in mining towns and Regional Colliery Hospitals under government administration have increased in number over the decades. There is a central hospital in Kalla (near Asansol) and two regional hospitals—one at Chora (near Durgapur) and the other one in Salanpur (close to Asansol) for medical treatment of colliery employees. Although the number of beds in the regional hospital has increased (Ghosh, 1974); yet, health infrastructure remains morbid in the collieries and mine areas as opposed to the cities, because there are limited number of health centers and hospitals. Infrastructural inadequacies necessitate the facilitation of upgraded healthcare for local population.

Regular monitoring of noise, water and ambient air is carried out by the area offices of ECL and the Central Mine Planning and Design Institute (CMPDI) in Asansol. Nevertheless, the steps taken fall short when protection of natural setting and human habitation are taken into consideration. The adoption of sustainable-integrated planning becomes necessary for framing policies and building alternative technology that would help decrease the dependence on nonrenewable resources.

A total of 14.56 km2 of land parcel has been acquired near the collieries of Bonjemehari and Gourandih for resettlement of local residents living in unstable areas near the collieries (Asansol Durgapur Development Authority, 2011). There is urgency of implementation of effective programs for resettlement and rehabilitation owing to the critical condition of environmental pollution in the urban areas of the region. The limited number of ground-plans and layouts of underground mines makes sand stowing and stabilization of underground voids difficult; under such circumstances shifting of settlements away from unstable areas to safer locations becomes an important social responsibility of the ECL (see Table 4). An article published in Counterview in 2015 draws attention to the complexities of enactment of rehabilitation plans because all components of resettlement on paper do not always easily materialize on the ground. Several years after the drafting of “Master Plan for Resettlement and Rehabilitation in Raniganj 2011,” it is still to be executed to full extent and work is yet to be realized (Shrimali, 2015). With passing time, distress of displacement and strain of relocation of residences, search of alternate livelihood, issues of health, responsibilities, and accountability keep mounting.

| Particulars of the master plan | Cases/occurrence | Estimated cost of rehabilitation (INR crore) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of fires | 7 | 40.28 |

| Number of sites to be rehabilitated | 139 | 2,610.1 |

| Area under unstable land (sq.km.) | 8.62 | |

| Sites with diversion of railway/pipelines | 7 | 2,661.73 |

- Data Source: Government of India (2011a).

5 CONCLUSIONS

Coal consumption and demand for coal continues to grow in India with increase in production and rise in the number of coal-based thermal power plants. A number of other factors also shape the importance of coal and its future in energy economy—environmental, social, and political issues being larger concerns. Coal mining serves as an important industry because coal as a fuel supports 56% of primary energy consumption and 76% of electricity production in the country.

Migration of laborers to the coal mines is mainly instigated by hopes of finding work and earning a living. In Raniganj Coalfield, the industrial space enclosed by the coal belt beheld a surge in migration when PSUs were commissioned between 1920s and 1960s; thereafter, the region registered a fall in the number of migrants. There has been a slight shift in employment and migration trends in the coalfield, owing to state policies and the productivity of the mines, that not only control coal economics but also the patterns of shift of residence of those migrating to the coalfield in search of work. Documentation of migrants shifting to the coal producing stretches of Raniganj has become obscure. Such a trend may be attributed to the fall in the rate of employment of permanent workers in the coal mines and in heavy industries. It is evident from field study that migration still continues in the region but due to larger proportion of migrants joining the informal sector as artisanal workers and occupants of small scale industries, it becomes difficult to corroborate the size of migrant population in the coalfield at present.

The unwarranted nature of economic engagement prevents migrant workers from earning the benefits of registered jobs, thus keeping the migrant workers away from assurance of safety and security. Social wellbeing and health therefore become important issues at the nodes of coal production. Review of welfare schemes for workers is essential because it is the workers who help reap the long-term benefits of production units. It is baffling on the part of the government, the employing company or mining authority to prevent informal operations at mine sites. Although the prevention of unscientific and informal methods of mining could help prevent hazards, it would also manifest into unemployment for many families. The circumstances under which laborers work and informally extract coal in the study area is exemplary, if the scenario of coal consumption in contemporary India is taken into consideration. Domestic coal consumption has a significant role to play in the industry dependent on informal coal mining. Despite lower prices of domestic coal than industrial coal (owing to its lower quality and larger proportion of impurities), accessibility to mines and easy procurement through pilferage makes unauthorized coal collection an attractive economic engagement even at the cost of health risks and social and environmental hazards. The efforts for protecting people as well as safeguarding the environment from the perils suffused by humans, give rise to a disconcerting quandary. Matters of safety and protection for mine laborers need to be placed under government scrutiny; mechanization and safe operation of machines also need to be considered in order to bring down susceptibility to accidents. Training of workers on application of mining techniques becomes important to help prevent accidents. Reinforcement of the plans and policies for sustained management of mines becomes indispensable at a time when the world is resorting to greener technologies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author is obliged to Professor Ranabir Samaddar, Distinguished Chair in Migration and Forced Migration Studies, Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata, for his guidance and valuable comments in enriching the research work. The author is thankful to Dr. Anita Sengupta, Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata, for her support. The author expresses heartfelt gratitude to Mr. Anand Shekhar, Head of the Department of Environment, Central Mine Planning, and Design Institute, Regional Institute I at Asansol. The author is grateful to all local residents dwelling in and around the collieries of Raniganj and nearby cities and the workers at the coal mines for sharing their experiences during field study and facilitating the research with their insightful narratives.

Biography

Shatabdi Das is Researcher at the Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata. She has recently submitted her PhD thesis in Geography at the University of Calcutta in Kolkata. Her research focuses on issues of migration, development and environmental impacts in urban areas.