Reporting and interpreting red blood cell morphology: is there discordance between clinical pathologists and clinicians?

Abstract

Background

Clinical pathologists (CPs) report RBC morphologic (RBC-M) changes to assist clinicians in prioritizing differential diagnoses. However, reporting is subjective, semiquantitative, and potentially biased. Reporting decisions vary among CPs, and reports may not be interpreted by clinicians as intended.

Objectives

The aims of this study were to survey clinicians and CPs about RBC-M terms and their clinical value, and identify areas of agreement and discordance.

Methods

Online surveys were distributed to small animal clinicians via the Veterinary Information Network and to CPs via the ASVCP listserv. A quiz assessed understanding of RBC-M terms among respondent groups. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze responses to survey questions, and quiz scores were compared among groups.

Results

Analyzable responses were obtained from 1662 clinicians and 82 CPs. Both clinicians and CPs considered some terms, eg, agglutination, useful, whereas only CPs considered other terms, eg, ghost cells, useful. All groups interpreted certain terms, eg, Heinz bodies, correctly, whereas some clinicians misinterpreted others, eg, eccentrocytes. Responses revealed that CPs often do not report RBC-M they consider insignificant, when present in low numbers. Twenty-eight percent of clinicians think CPs review all blood smears while only 19% of CPs report reviewing all smears.

Conclusions

Important differences about the clinical relevance of certain RBC-M terms exist between clinicians and CPs. Inclusion of interpretive comments on CBC reports is the clearest way to ensure that RBC-M changes are interpreted as intended by the CP. Reporting practices should be examined critically to improve communication, transparency, and ultimately medical decisions.

Introduction

Terms that indicate RBC morphology (RBC-M) are included on CBC reports to provide clinicians with data beyond cell enumeration and RBC indices. RBC-M terms may convey qualitative information about disease processes and, when correctly interpreted, assist clinicians in prioritizing differential diagnoses. However, as RBC-M reporting standards do not exist, reporting is subjective, semiquantitative, and potentially biased. Clinical pathologists (CPs) differ in how they name, report, and interpret RBC-M changes1; some report every change in RBC-M, whereas others report only those they believe are clinically relevant in a particular case. The majority of RBC-M reporting relies on an arbitrary, nonstandardized, ordinal scale (eg, 1+ to 4+, or “few,” “moderate,” or “many”). CPs decide whether or not to include a comment to explicitly convey their interpretation of these findings to the clinician. In the absence of case-specific interpretative comments, certain RBC-M terms might be ignored by the clinician, or the clinician's conclusion about the meaning and importance of the RBC-M might differ substantially from that intended by the CP. Therefore, potential problems lie not only in the variation of reporting among CPs but also in the potential misinterpretation of the clinical significance of RBC-M.

Similar challenges exist in human medicine. In one study, perceptions of hematology specialists and pediatric clinicians (nonhematology specialists) about the clinical utility of RBC-M reporting in general and the clinical value of specific RBC-M terms were assessed.2 Less than half the clinicians found RBC-M reports to be clinically useful. In addition, a large proportion of clinicians reported uncertainty of the clinical relevance of some RBC-M terminology. The authors suggested a need for educational initiatives and omission of RBC-M terms that neither group found clinically useful. Similar data and recommendations are lacking in veterinary medicine.

In this study, we aimed to examine perceptions of veterinary CPs and clinicians regarding the clinical value of RBC-M terms, and to identify potential areas of disconnect between these groups. Specific areas of focus included understanding of RBC-M among clinicians, perceptions of clinicians regarding the role of the CP in reviewing blood smears, and RBC-M reporting practices among CPs.

Methods

This prospective study was designed as a set of surveys administered to convenience samples of small animal clinicians with varying levels of clinical expertise and to veterinary CPs. Separate surveys were developed for each group with slight differences that reflected the unique professional roles of each group (see Appendix S1 for complete surveys). Specific RBC-M terms used in the survey were based on those used by CPs in the Cornell Veterinary Clinical Pathology Laboratory (Table 1).

| RBC morphologic terms | |

|---|---|

| Acanthocyte | Keratocyte |

| Agglutination | Macrocyte |

| Anisocytosis | Ovalocyte/elliptocyte |

| Basophilic stippling | Poikilocytosis |

| Eccentrocyte | Polychromasia |

| Echinocyte | Rouleaux |

| Echino-elliptocyte | Schistocyte |

| Ghost cell | Siderocyte |

| Heinz body | Spherocyte |

| Howell–Jolly body | Stomatocyte |

| Hypochromasia | Target cell |

Survey

Clinicians were invited to participate in the online survey via a member-wide email distributed to members of the Veterinary Information Network (VIN). A qualifying question verified that clinicians actively worked with small animals, and asked them to identify themselves as general practitioners or specialists. Veterinarians who were not in small animal practice were redirected to the end of the survey. Student members of VIN were redirected to the quiz portion. CPs were invited to participate in a CP-specific version of the online survey via the ASVCP email listserv once, with a subsequent single reminder email. The surveys were opened on April 26, 2013 and data were collated for analysis on May 15, 2013.

For each RBC-M term, respondents were asked to select all terms that were familiar to them and to rank each term based on their opinion of its clinical value (“very useful,” “useful,” “sometimes useful,” or “not useful or clinically insignificant”). Respondents could also select “do not know this term.” Responses of clinicians were subdivided into those from general practitioners (GP) and specialists (referring to a nonclinical pathologist specialist).

Quiz

The same 10-question quiz was administered to both survey groups (clinicians and CPs). The aim of the quiz was to objectively verify the reported familiarity of a clinician or CP with RBC-M terms, recorded earlier in the survey. Students were permitted to take only the quiz. The quiz questions tested knowledge of the clinical relevance of RBC-M, rather than identification of the morphologic appearance on an image. Four board-certified CPs from Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine were consulted about the composition of quiz questions prior to survey distribution.

All quiz questions included 2 standard options: “none of the above” and “I do not know.” Respondents could select any or all of the options. However, if they selected “none of the above” or “I do not know” in addition to other responses, only “none of the above” or “I do not know” was considered as their answer. The quiz was scored using the following rubric: 1 point for a correct answer, −0.5 point for an incorrect answer, and 0 point (no penalty or award) for selecting “I do not know.” Responses were analyzed by group: student, GP, specialist (nonclinical pathologist specialist), and CP.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (percentages) were examined for all survey questions. Summary statistics were examined for quiz responses by group. Quiz scores were tested for normality using a Shapiro–Wilk test. If scores were not normally distributed, differences in quiz scores between groups were analyzed using a Kruskal–Wallis test, with a Dunn's Multiple Comparison Test.

Results

Survey respondents

The survey respondents consisted of 225 students, 1662 clinicians, and 82 CPs. Of the clinicians, 1532 were GPs and 130 were board-certified non-CP specialists (including nonresidency ABVP board-certified practitioners). The CP group included 14 residents, 51 board-certified CPs, and 9 other CPs (including board-eligible and nonboard-certified CPs). Six board-certified CPs and 2 other CPs mistakenly took the clinician survey on VIN. Therefore, only the quiz data from these 8 respondents were included to prevent inclusion of CP responses among clinician responses. Not all respondents provided answers to every question, resulting in a variable number of responses for each question.

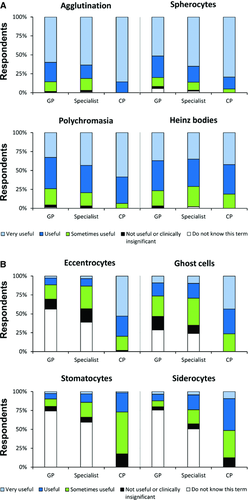

Variability between groups in perceived clinical utility of RBC morphologic changes

For clinicians, 80% (1306/1631) reported they “always” read the RBC morphologic changes if provided on CBC reports, with 14% (220/1631) “frequently” doing so. Examining the utility reported for each RBC-M term revealed discrepancies between clinicians and CPs. Terms that produced a similar distribution among groups of respondents in the various utility categories across all groups sampled were considered to have high agreement (Figure 1A); these terms tended to be those found useful to a large proportion of respondents. For other terms, responses varied greatly between groups (Figure 1B). Lack of understanding of RBC-M terms by clinicians (selecting “do not know this term”) accounted for most of the disagreement about the clinical utility of the term. Only 9% of clinicians (107/1189) indicated, “I always know the meanings of all morphologic RBC terms used in reports.” The 10 RBC-M terms with the highest percentage of clinician respondents designating “do not know this term” were tabulated to inform CPs of this knowledge gap (Table 2). Many of the terms in this list are those that most CPs reported as “sometimes useful” or “not useful or clinically insignificant” (Table 3). However, several of the RBC-M terms, such as eccentrocytes and ghost cells, were reported as “sometimes useful” or “not useful or clinically insignificant” by clinicians, but were reported as “very useful” by most CPs (Figure 1B). Graphs of all responses about the clinical utility of RBC-M terms are found in Figure S1.

| General Practitioner (984–1086)a | % | Specialist (88–97)a | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Echino-elliptocyte | 85 | Echino-elliptocyte | 77 |

| Siderocyte | 76 | Stomatocyte | 59 |

| Ovalocyte/elliptocyte | 74 | Ovalocyte/elliptocyte | 52 |

| Stomatocyte | 74 | Siderocyte | 51 |

| Keratocyte | 57 | Keratocyte | 43 |

| Eccentrocyte | 56 | Eccentrocyte | 39 |

| Echinocyte | 36 | Ghost cell | 24 |

| Ghost cell | 29 | Echinocyte | 23 |

| Macrocyte | 29 | Macrocyte | 18 |

| Schistocyte | 13 | Target cell | 10 |

- a Number of respondents (minimum–maximum).

| Clinical Pathologist (61–64)a | % | Specialist (88–97)a | % | General Practitioner (984–1086)a | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echinocyte | 94 | Echinocyte | 58 | Acanthocyte | 48 |

| Howell–Jolly body | 83 | Acanthocyte | 57 | Ghost cell | 45 |

| Target cell | 79 | Rouleaux | 53 | Echinocyte | 43 |

| Echino-elliptocyte | 73 | Howell–Jolly body | 52 | Rouleaux | 43 |

| Ovalocyte/elliptocyte | 73 | Target cell | 51 | Basophilic stippling | 42 |

| Stomatocyte | 73 | Eccentrocyte | 48 | Howell–Jolly body | 40 |

| Rouleaux | 68 | Ghost cell | 47 | Target cell | 40 |

| Macrocyte | 59 | Ovalocyte | 44 | Poikilocytosis | 39 |

| Keratocyte | 58 | Keratocyte | 42 | Macrocyte | 34 |

| Poikilocytosis | 57 | Poikilocytosis | 40 | Eccentrocyte | 32 |

- a Number of respondents (minimum–maximum).

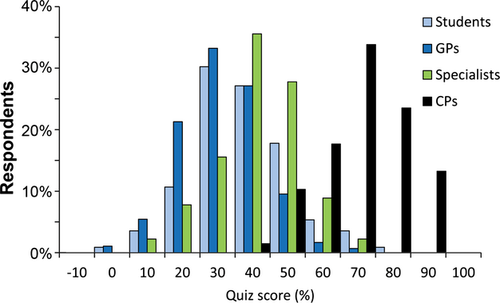

Quiz

GPs had the lowest scores (median, interquartile range: 27%, 19–33%), followed by students (29%, 23–37%), specialists (38%, 29–46%), and CPs (67%, 60–73%). Scores were not normally distributed, and using a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Dunn's Multiple Comparison Test, the difference between the CP median score and the median scores from all other groups was significant, as was the difference between the median scores of the specialists and GPs (P < .05). The medians were not different between students and either GPs or specialists (Figure 2).

The quiz questions (select questions in Table 4) highlighted RBC-M terms that clinicians and students understand well, as well as those that are misunderstood or unfamiliar. Answers to question 1 revealed that within a defined group of RBC morphologic changes associated with a similar mechanism (ie, oxidative damage), Heinz bodies are recognized, yet most students and clinicians missed the significance of eccentrocytes.

| Students (225)a | GPs (1134) | Specialists (92) | CPs (67) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1: Which RBC morphologic term(s) do you associate with oxidative damage of RBCs? | ||||

| Heinz bodies | 90% | 81% | 92% | 99% |

| Eccentrocytes | 22% | 11% | 26% | 97% |

| Most common incorrect answer | Acanthocytes (10%) | Howell–Jolly body (14%) | Ghost cells (10%) | Ghost cells (19%) |

| I do not know | 2% | 10% | 3% | 0% |

| Students (225) | GPs (1042) | Specialists (92) | CPs (67) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 2: What is the significance of ghost cells? | ||||

| Associated with intravascular hemolysis | 48% | 30% | 42% | 100% |

| Most common incorrect answer | More severe degree of hypochromasia (20%) | More severe degree of hypochromasia (17%) | More severe degree of hypochromasia (20%) | None of the above (3%) |

| I do not know | 11% | 28% | 25% | 0% |

| Students (225) | GPs (1030) | Specialists (91) | CPs (67) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 8: What does rouleaux clinically suggest to you? | ||||

| Hyperglobulinemia | 35% | 22% | 42% | 100% |

| Most common incorrect answer | Artifact of smearing (33%) | IMHA (47%) | Artifact of smearing (37%) | Normal for small animal (16%) |

| I do not know | 4% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

| Students (221) | GPs (1029) | Specialists (90) | CPs (67) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 10: Which RBC morphologic change(s) do you associate with bone marrow myelofibrosis? | ||||

| Ovalocytes | 5% | 4% | 7% | 61% |

| Most common incorrect answer | None of the above (20%) | None of the above (11%) | None of the above (37%) | None of the above (25%) |

| I do not know | 61% | 77% | 43% | 6% |

- a Number of respondents.

Quiz responses also permitted assessment of a respondent's reported familiarity with an RBC-M term. For example, 98% of GPs (1462/1498) and 97% of specialists (123/127) reported familiarity with Heinz bodies earlier in the survey, and a nearly identical percentage of GPs and specialists correctly selected Heinz bodies as associated with oxidative injury; however, 37% of GPs (560/1498) and 57% of specialists (72/127) reported familiarity with eccentrocytes, but there was a considerably lower percentage of correct responses to the question designed to test understanding of this RBC-M term (Table 4, question 1). A similar discrepancy in perceived understanding and quiz performance was evident in question 2, where 65% of GPs (977/1498) and 70% of specialists (89/127) reported familiarity with ghost cells, but a lower percentage in each group correctly answered the quiz question that tested understanding of this morphologic change (Table 4). Question 8 revealed a considerable gap in knowledge among clinicians; 97% of GPs (1452/1498) and 98% of specialists (125/127) reported familiarity with rouleaux, yet less than half of respondents in both groups correctly chose hyperglobulinemia as a cause of this RBC-M (Table 4). For CPs the most frequently reported incorrect answers to quiz questions can also provide insight into how these RBC-M terms are sometimes misinterpreted (Table 4).

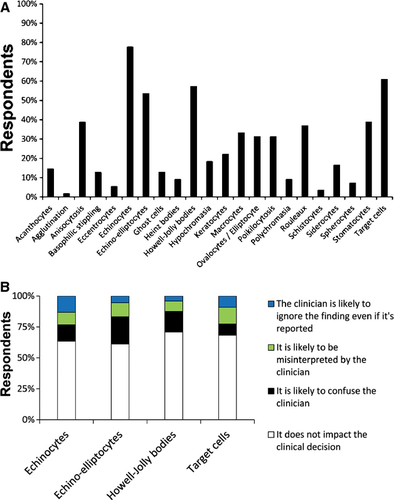

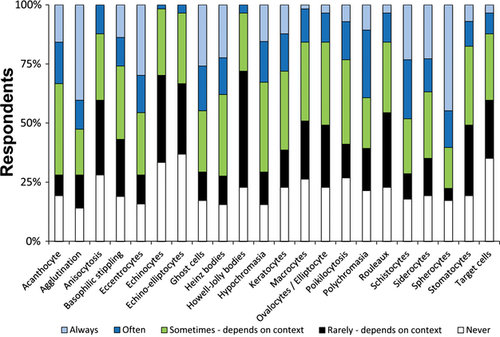

Reporting of RBC morphology by clinical pathologists

CPs were asked which RBC-M terms (if any) they would choose not to report if there were low numbers present (rare or 1+) (Figure 3A). The 4 RBC-M terms that the highest percentages of CPs would not report were echinocyte (78%, 42/54), target cell (61%, 33/54), Howell–Jolly body (57%, 31/54), and echino-elliptocyte (54%, 29/54). CPs tended to have similar reasons for their decision not to report each of these RBC-M terms (Figure 3B). These 4 RBC-M terms were also identified by most CPs as “sometimes useful” or “not useful or clinically insignificant” (Table 3). For all of the RBC-M terms except stomatocytes in the CPs' list of Table 3, most CPs responded that each morphologic change was significant only when present with other RBC abnormalities. Many CPs (42%, 21/50) found stomatocytes to be significant only when there are “many” (3+) on the smear. In reading comments from clinicians, there is no clear consensus about whether they prefer that only clinically relevant or all RBC-M changes be reported (Table 5). Finally, CPs were asked if they preferred reporting RBC-M changes on an ordinal scale (1+, 2+, etc) or a descriptive scale (few, moderate, many, etc); 44% (26/59) preferred a descriptive scale, 29% (17/59) preferred an ordinal scale, and 25% (15/59) responded that it depends on the specific morphologic finding.

| Clinician | CP | |

|---|---|---|

| Reporting | “I suggest reporting only the clinically significant findings… because we sometimes end up with a long list of changes that does not provide any help for the diagnostic approach.” | “I think we should move away from reporting general comments (poikilocytosis, anisocytosis) and instead focus on the exact type that is clinically relevant (ie, spherocytes, schistocytes, macrocytes, etc).” |

| “I prefer to have all abnormal results reported in detail.” | “I believe the 1–4+ scale gives a wrong impression of the precision of reporting. These observations are very subjective…” | |

| Indications for CP slide review | “We do most of our CBCs in house, which are read by an experienced lab tech. If I sent out to a lab, I absolutely expect that a clinical pathologist will read the slide. Otherwise, why send it?” | “In our lab, a med tech looks at a smear from every CBC we do. They use medical review criteria to determine when to forward smears to pathologist for review. We also review if a clinician requests it or a med tech just wants help (even if not specifically a review criterion).” |

| “Other than thinking that all that are sent are reviewed, we may call if trying to work out a correlation with the clinical picture presented by the patient…” | “We have a criteria checklist for pathologist review… We examine approximately 20% of submitted CBC smears.” | |

| Interpretative comments | “I count on the pathologist to comment on their significance, not just their presence.” | “Clinicians should be able to interpret common RBC morphologic changes on their own. These morphologies are taught to veterinary students via a clinical pathology course in vet school. The clinical pathologist can be contacted for consultation if needed.” |

| “Our main lab has a tendency to ‘cut & paste’ comments so they are not specific to the case, which can be frustrating.” | “As a teaching institution, we often do not interpret morphologic changes to allow students the opportunity to do so. On the other hand, sometimes we do review and provide interpretive comments and the clinicians make decisions and send the animal home before receiving or interpreting the changes correctly.” |

Blood smear review

For 79% of clinicians (1313/1662), their practices have the capability of performing in-clinic CBCs, and 59% (772/1309) reported that they, or their staff, routinely examine blood smears in conjunction with an automated CBC. Regarding use of a referral laboratory, 16% of clinicians (263/1662) reported that they submit every blood sample to a referral laboratory, 35% (587/1662) submit most samples, 27% (448/1662) submit some samples, 21% (341/1662) submit few samples, and 1% (23/1662) never submit CBC samples to a referral laboratory.

More than a quarter of clinicians surveyed (28%, 464/1633) believe that a CP reviews every submitted blood smear. In contrast, 19% of CPs (14/74) reported that their routine practice is to review all blood smears. Similarly, 67% of CPs (49/73) perceived that clinicians do not expect all blood smears to be reviewed and evaluate smears only when necessary.

When clinicians reported the most common reason for requesting a CP review of a CBC or blood smear and CPs reported the most common reason they reviewed blood smears, 38% of clinicians (607/1609) and 26% of CPs (19/74) selected “one or multiple cytopenias.” However, 30% of CPs (22/74) indicated “other” and were given the opportunity to explain the reason. For many, the laboratory's standard operating procedures specify that a technologist reviews the blood smear first and then refers the smear for CP review if certain criteria are present. CPs also indicated they review smears if the technologist has a question or is uncertain about the findings. In examining free response comments, low numbers of clinicians seemed aware of the initial review by a technologist; these clinicians added that “any significant cell morphology abnormalities” or “abnormal hemograms” would initiate an automatic CP review. These vague statements suggest a lack of knowledge of the specific review criteria. For example, one clinician stated, “I would like to know my individual laboratory's indications for pathologist review.” A few clinicians also commented that they are deterred by an additional fee charged by the laboratory for a requested CP review. Other clinicians seem to be unaware of the common practice of clinical pathology laboratories having an established list of review criteria initiating CP review of blood smears (Table 5).

Interpretive comment

Most CPs (93%, 51/55) indicated that their laboratory “sometimes” provides an interpretive comment from a CP on CBC reports. Respondents were allowed to select all the applicable reasons that would prompt them to add an interpretive comment. The most frequently reported reason was “neoplastic cells identified or suspected” (93%, 50/54). A majority of CP respondents (63%, 34/54) indicated that RBC morphologic changes would prompt them to include an interpretive comment, with variable percentages of CPs providing interpretative comments in association with selected morphologies (Figure 4).

Similarly, 71% of clinicians (859/1213) indicated that their clinical pathology laboratory “sometimes” provides an interpretive comment from a CP on CBC reports, whereas 20% (247/1213) indicate there is “always” an interpretive comment. For clinicians, 91% (995/1093) reported “always” reading interpretive comments from the CP, and 75% reported that comments were “very useful” or “useful.” However, when CPs were asked how clinically useful they thought submitting clinicians find their interpretive comments, 42% (26/61) responded “sometimes useful,” 38% (23/61) responded “useful,” and only 20% (12/61) responded “very useful.” None of the clinicians responded that they never read the comments or never find them clinically useful. In fact, 81% (920/1140) indicated they would prefer to have an interpretive comment from a CP on all CBC reports that have RBC-M changes, and 75% of CPs (45/60) speculated that submitting clinicians would prefer this. The remaining 19% of clinicians (220/1140) indicated they preferred comments only when necessary.

Discussion

Our study identified discrepancies between CPs and clinicians in how each group interprets the significance and utility of RBC-M terms and in the awareness of the other group's needs, standard procedures, and knowledge of RBC-M reporting practices. To improve the working relationship between CPs and clinicians, and ultimately patient care, knowledge gaps and misconceptions should be discussed openly.

Misinterpretation of the significance of RBC-M terms by clinicians and lack of awareness of this misinterpretation by CPs both result in undesirable consequences. Although several clinicians in our survey commented that they look up unfamiliar terms on a CBC report, this step requires awareness of one's knowledge and limitations to be an effective checkpoint. Lack of an objective means to verify a respondent's reported familiarity with an RBC-M term was a weakness in another study.2 We addressed this by including a quiz, and performance of clinicians revealed a gap between their self-assessed familiarity with certain RBC-M terms and their knowledge of the terms' significance. For example, despite the reported familiarity with rouleaux, misinterpretation of its significance by many clinicians and students could lead to misdiagnosing immune-mediated hemolytic anemia or ignoring the finding as artifact. Many clinicians did not associate the presence of eccentrocytes with oxidative injury or incorrectly associated ghost cells with iron deficiency. Unfortunately, in most cases the CP would be unaware of these misinterpretations and would probably assume that clinicians understand the clinical relevance of the CBC findings. One could argue that veterinary students are taught the significance of RBC-M in veterinary school; however, our results show that veterinary students did not perform better than GPs or non-CP specialists, suggesting the problem is not simply a loss of information with time. To provide the best service to clinicians, CPs need to have an accurate estimate of the knowledge base of clinicians, particularly when lists of RBC-M terms are provided on CBC reports with no interpretative comment.

Both groups can take steps to prevent potential misdiagnoses or loss of helpful information, and to help bridge the gap between clinicians and CPs. Inclusion of interpretive comments on CBC reports is the clearest way to ensure that RBC-M changes are interpreted as intended by the CP. Addition of these comments has also been recommended in human medicine to address overestimation of clinicians' knowledge of RBC-M terms and their clinical relevance.3 Interestingly, CPs in our study included interpretive comments more often for RBC-M terms that clinicians understand well (ie, spherocytes and agglutination), and less often for those that are not as well understood (ie, echinocytes and target cells). Perhaps CPs should consider providing comments that help clinicians interpret clinically relevant findings, and that also provide guidance on changes that are artifactual or of unknown importance. To provide a useful interpretive comment tailored to a specific case, the CP needs complete, yet succinct, information about the patient's history and pertinent diagnostic findings. However, this information is often not provided, possibly because clinicians believe that a CBC is an isolated automated test, which CPs should evaluate in a blinded manner to prevent bias, or are unaware that CPs approach evaluation of a blood smear in a similar fashion to a cytologic smear.4 As is true for many diagnostic tests, the best interpretation is made when all clinical information is considered; lack of relevant information leads to an increased likelihood of error.4 We acknowledge that providing interpretative comments has the potential to decrease learning opportunities at teaching institutions. Our data indicated that clinicians generally want interpretive comments and CPs are generally aware of this desire; however, time constraints and caseload volume are limiting factors.

Transparent RBC-M reporting and blood smear review practices would foster a strong working relationship between clinicians and CPs, and minimize confusion among clinicians. Clinicians should be aware that CPs may choose to omit certain RBC-M changes they consider to be clinically insignificant. However, this practice could lead to loss of data for retrospective studies that rely on CBC results. In retrospect, it would have been interesting to ask clinicians and CPs in our survey which method they prefer. There is a general agreement that improved consistency in cytologic diagnosis reporting would be valuable, and the same argument can be made for RBC-M reporting.5 To help minimize confusion created by RBC-M terms, perhaps certain terms that no group finds useful should be eliminated from CBC reports, as suggested previously.2 For example, few clinicians and CPs classified poikilocytosis as “very useful” and eliminating this term as a nonspecific term that is not clinically helpful in small animals could be considered; however, in ruminants, poikilocytosis is sometimes the most appropriate term to characterize RBC-M. Regarding blood smear review by CPs, the presence of any RBC-M changes on a blood smear does not signal a review in our laboratory and probably does not in other laboratories. Review of all blood smears with RBC-M changes by CPs is impractical, given daily workload and time constraints. The criteria for review are not the problem; rather, confusion arises because clinical pathology laboratories do not communicate these criteria to clinicians. Increased transparency about how results are generated and reported would help clinicians understand when a blood smear is reviewed by a CP and would lead to more realistic expectations and improved client communication when clinicians convey the value and cost of diagnostic tests to clients.

The survey used in our study asked about “small animals” rather than specific species to limit both the length of the survey and interpretations based on species-specific factors; obviously, certain RBC-M terms are interpreted differently for dogs and cats. A significant limitation of the study was the low number of CP respondents, due in part to the small size of the sample pool compared with the pool of general practitioners and non-CP specialists. Additionally, because we did not want to further restrict the pool of CPs, the quiz was constructed without input from CPs outside our institution; thus, institutional bias may have been present in the selection of “correct” and “incorrect” answers. Some responses that indicated misunderstanding of terms may have been the result of how the quiz was constructed.

This prospective study of the utility of RBC-M terms reported as a part of the CBC confirmed that CPs and clinicians have misconceptions about how each group defines and interprets the terms and what procedures are used by the laboratory. Acknowledging these misconceptions should open the door to improved communication and understanding between the groups. Although CPs often are geographically distant from clinicians, laboratory procedures and how and when RBC-M changes are interpreted can be more transparent. Clinicians can supply relevant information so CPs are able to interpret morphologic changes in the correct context, and CPs may include an interpretive comment to clearly ensure that RBC-M changes are interpreted as they intend. We hope this study encourages broad discussion among CPs, clinicians, and laboratory technicians about current practices and needs relevant to RBC-M reporting to improve care delivered to patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karen Young, University of Wisconsin-Madison, for her assistance in preparing the manuscript.