Pharmaceutical cost-sharing systems and savings for healthcare systems from parallel trade

Abstract

This paper studies the consequences of parallel trade in a two-country model. It compares a coinsurance scheme (consumers pay a percentage of the drug price) and an indemnity insurance scheme (reimbursement is independent of the drug price) with respect to changes in copayments and public health expenditure. In the destination country, copayments for patients decrease to a larger extent under indemnity insurance, whereas reductions in public health expenditure occur only under coinsurance. In the source country, copayments increase less under coinsurance, whereas health expenditure is reduced more under indemnity insurance. In both countries, total expenditure under parallel trade is lower.

1 INTRODUCTION

This paper studies the consequences of parallel trade, that is, trade outside the manufacturer's authorised distribution channel, on healthcare systems. In particular, a coinsurance scheme (consumers pay a percentage of the drug price) and an indemnity insurance scheme (reimbursement is independent of the drug price) are compared with respect to changes in copayments and public health expenditure under parallel trade.

Over the last decades, healthcare expenditure has risen sharply in many countries. Governments typically regulate pharmaceutical prices directly, for example, via price caps. Another approach to containing pharmaceutical expenditure is promoting the substitution of higher priced brand-name drugs by less expensive equivalents. This may include generic versions after patent expiry. Alternatively, parallel imported drugs are de facto identical, lower priced versions of (locally sourced) brand-name drugs, which are imported without the permission of the manufacturer. That is, wholesalers or parallel traders may buy the drug in one country and resell it in another country where the price is higher (Vandoros & Kanavos, 2014). Parallel imports are legal within the European Economic Area but excluded if coming from non-member states (Ganslandt & Maskus, 2007; Maskus, 2000). Substantial price differences between countries give rise to this kind of arbitrage.1 These price differences may emerge from pharmaceutical manufacturers price-discriminating between different countries and/or different national pharmaceutical regulations (Enemark, Møller Pedersen, & Sørensen, 2006; EU Commission, 2003). Pharmaceutical parallel trade had a volume of €5.4 bn in the European Union in 2015 (EFPIA, 2017). Destination countries are high-price countries, for example, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark, where pricing is relatively free; source countries are characterised by strict price regulation, for example, Spain, France, Portugal, Greece and Italy (Kanavos & Costa-Font, 2005).2

Whereas the exploitation of these arbitrage opportunities is intended to contain pharmaceutical expenditure in the destination countries, empirical evidences ambiguous. Kanavos, Costa-Font, Merkur, and Gemmill (2004) find no evidence for savings created by parallel imports,3 whereas West and Mahon (2003) conclude that parallel trade generates considerable savings.4 Also, Enemark et al. (2006) find that parallel trade gives rise to significant savings, both direct to patients and health insurances.5 However, these studies emphasise the importance of the cost-sharing system. Rules of copayment and reimbursement are important factors in determining the effect of parallel trade, that is, the level of savings and the split of savings between health insurances and patients (Enemark et al., 2006; Kanavos et al., 2004).6

For patients, the cost-sharing system is the direct channel through which they benefit from purchasing parallel imports (Kanavos et al., 2004). Patients are more likely to purchase cheaper parallel imports, the more they are exposed to the price difference between drugs. For example, a flat fee copayment fails to sensitise patients for price differences. A coinsurance rate, however, makes patients benefit from choosing a cheaper drug.

Also for health insurance, the cost-sharing system determines the level of savings. If a percentage of the price is reimbursed by health insurances, lower drug prices translate to lower public pharmaceutical expenditure. Furthermore, as copayment rules provide incentives for patients to buy parallel imports, cost-sharing determines the competitive pressure by parallel trade. Accordingly, public health expenditure is reduced by more if competition from parallel trade is strong and the market share of parallel imports is high. Consequently, the cost-sharing system is both a driver of parallel trade, as it determines cross-country price differences, and, more importantly, an important factor in determining savings from parallel trade.

In the European Union, member states typically apply some form of cost-sharing for pharmaceuticals, mostly in the form of coinsurance (Espin & Rovira, 2007). In Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Finland, Portugal, and Spain, for instance, patients pay a percentage of the drug price. In some countries, for example, Belgium and Denmark, coinsurance rates vary with drug classes and/or out-of-pocket expenditure (Espin & Rovira, 2007). In a few member states, for example, Austria, Italy, and the UK, patients pay a flat fee, this is a lump-sum copayment. Some member states, for example, Ireland and Sweden, apply a deductible, where patients pay expenditures up to a certain threshold out-of-pocket (Espin & Rovira, 2007). Also, reference pricing, where the regulator sets a maximum reimbursement amount (reference price) for a group of interchangeable pharmaceuticals, can be found among others in Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain (Bongers & Carradinha, 2009).

The importance of cost-sharing systems for the consequences of parallel trade has attracted surprisingly little attention in the literature.7 Jelovac and Bordoy (2005) show in a vertical differentiation model with horizontal arbitrage that, if differences in cost-sharing systems trigger parallel trade, it reduces welfare. Based on the Jelovac and Bordoy (2005) model, Köksal (2009) compares price effects caused by parallel trade under coinsurance and reference pricing. Under reference pricing, price reductions from parallel trade in the destination country are higher than under coinsurance, while the price in the source country remains unchanged. Vandoros and Kanavos (2014) show in a game-theoretic model that parallel trade does not affect the price for a locally sourced drug and that the parallel import is priced at the locally sourced version's price unless parallel trade-enabling policies such as copayments or quotas generate downward pressure. Birg (2015) shows that nationally determined changes in coinsurance rates may result in spillovers and enhance or mitigate the effect of parallel in source and destination country.

This paper studies the effect of parallel trade on healthcare systems, focusing on the level of savings and the split of savings, under two cost-sharing systems. It compares coinsurance (consumers pay a percentage of the drug price) and indemnity insurance (reimbursement is independent of the drug price) with respect to changes in copayments and public health expenditure. Both cost-sharing schemes can be considered policy alternatives. Coinsurance is commonly applied in European member states. Indemnity insurance is a textbook example for a cost-sharing system, but cannot be found in pure form in any member state of the European Union. With regard to price sensitivity, indemnity insurance shares a feature with deductibles, namely that patients are fully exposed to price differences if their out-of-pocket expenditure is below the threshold. However, the non-continuous design of a deductible creates modelling difficulties—below the threshold, patients pay the full price out-of-pocket, which is equivalent to no insurance coverage; above the threshold, patients pay a percentage of the price, which is equivalent to coinsurance, or there is full reimbursement, making demand perfectly price-inelastic. Moreover, by making reimbursement independent of drug choice, indemnity insurance is similar to reference pricing. But whereas indemnity insurance is a cost-sharing instrument, reference pricing is an instrument of price regulation which is applied in addition to a cost-sharing instrument, usually coinsurance. This is, reimbursement under the reference price is price-dependent up to the reference price and only includes a price-independent element for drug prices above the reference price, whereas under indemnity insurance reimbursement is completely price-independent. Vice versa, patients are fully exposed to price differences under indemnity insurance, whereas under the reference price, patients are only fully exposed to price differences for prices above the reference price. This paper considers stylised versions of both cost-sharing systems to highlight the general impact of price-dependent and price-independent reimbursement for the effect of parallel trade.8

Against this background, this paper explores the role of cost-sharing for the effect of parallel trade in a two-country model following Maskus and Chen (2002, 2004) and Chen and Maskus (2005).9 It assumes a manufacturer that sells a drug in two markets. Parallel trade occurs as a by-product of the vertical control structure. Other than Jelovac and Bordoy (2005), Köksal (2009), and Vandoros and Kanavos (2014) who consider parallel trade as retail-level horizontal arbitrage, this paper explains parallel trade as vertical arbitrage: indirect sales through an intermediary are the trigger for parallel trade. Commonly, pharmaceutical manufacturers sell not directly, but through independent wholesalers (Taylor, Mrazek, & Mossialos, 2004). Accordingly, the largest share of parallel trade involves the wholesale level (Maskus & Chen, 2002). Parallel trade is mainly determined by the price difference between the wholesale price and the retail price in the destination country. The approach of this paper separates the cause for from the consequences of parallel trade. Horizontal arbitrage is triggered by retail price differences and accordingly, differences in the cost-sharing system. That is, in Jelovac and Bordoy (2005) and Köksal (2009), the design of the cost-sharing system is the determining factor for whether parallel trade occurs, but also for what consequences parallel trade has. For vertical arbitrage, however, parallel trade would occur even for identical cost-sharing systems and/or identical copayments. This allows the analysis of the interaction between cost-sharing systems and parallel trade also for identical cost-sharing systems.

In the destination country, savings for patients occur under both systems, with savings being relatively higher under indemnity insurance. Savings for health insurance occur only under coinsurance, as indemnity insurance fails to link reimbursement to drug prices. In the source country, the drug price increase following the increase in the wholesale price results in additional expenses for consumers under both cost-sharing systems. Under coinsurance, additional expenses are relatively lower. Parallel trade results in lower health expenditure in the source country under both cost-sharing systems, with the relative reduction in health expenditure being higher under indemnity insurance. In both countries, total expenditure under parallel trade is lower, independent of the cost-sharing system.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. In the next section, the model is presented, and the case of no parallel trade and the case of parallel trade are analysed. In Section 3, the effects of parallel trade with respect to changes in copayments and public health expenditure are studied. Section 4 discusses assumption ot the model. Section 5 concludes.

2 THE MODEL

Consider a manufacturer M that sells a brand-name drug b in two countries, his home country D and a foreign country S.10 The manufacturer sells directly to the consumers in D; but in the foreign country S, he sells through an independent intermediary I. The manufacturer charges the intermediary a wholesale price w and a fixed fee ϕ, allowing him to extract the intermediary's profit and to avoid the double-marginalisation problem.

The intermediary may engage in parallel trade and resell the drug (hereafter noted as β) in D. That is, the foreign country is the source country of the parallel import and the home country is the destination country. Therefore, the home country will be denoted as D and the foreign country as S.

Consumers in D may buy the locally sourced version b or the parallel import β. Due to differences in appearance and packaging between the locally sourced version of the drug and the parallel import (see Maskus, 2000), consumers associate a lower quality with the parallel import, which is captured by a discount factor τ in consumer valuation.11 Consumers in S buy the drug from the intermediary.

Consumers in both countries are heterogeneous with respect to the gross valuation of the drug, represented by a parameter θ which is uniformly distributed on the interval [0,1]. Thus, the total mass of consumers is given by 1 in both countries. The consumer heterogeneity with respect to valuation θ can be interpreted as differences in willingness to pay for a locally sourced version, differences in risk aversion regarding the trial of substitutes or differences in the severity of the condition or differences in prescription practices (see e.g., Brekke, Holmas, & Straume, 2011).

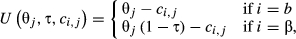

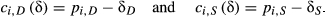

(1)

(1) reflects the perceived quality difference between versions b and β12 and ci,j is the patient copayment for drug i in country j (j = D, S). The utility derived from no drug consumption is zero.

reflects the perceived quality difference between versions b and β12 and ci,j is the patient copayment for drug i in country j (j = D, S). The utility derived from no drug consumption is zero. . Hence, in country D, demand for

. Hence, in country D, demand for  is given by:

is given by:

(2)

(2) , while a consumer who is indifferent between buying the parallel import (β) and not buying at all (0) has a gross valuation

, while a consumer who is indifferent between buying the parallel import (β) and not buying at all (0) has a gross valuation  . Consequently, demand for the authorised product

. Consequently, demand for the authorised product  and for the parallel import β is given by:

and for the parallel import β is given by:

(3)

(3)An asterisk is used to denote variables associated with parallel trade.

In country S, the brand-name drug is only sold by the intermediary. A consumer who is indifferent between buying the drug and not buying has a gross valuation  .

.

(4)

(4)Production technologies exhibit constant marginal costs, which are normalised to zero. It is assumed that parallel trade is costless.13

The structure of the model can be summarised by the following two-stage game: in the first stage, the manufacturer specifies a wholesale price w and fixed fee ϕ. In the second and final stage, the intermediary and manufacturer set retail prices.

2.1 Coinsurance

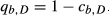

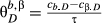

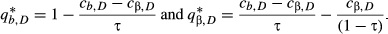

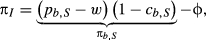

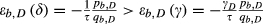

(5)

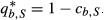

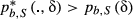

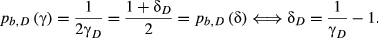

(5)If parallel trade is not allowed, the consumer indifferent between b and not purchasing is given by  . Under parallel trade, the consumer indifferent between b and β is given by

. Under parallel trade, the consumer indifferent between b and β is given by  . For the choice between the two versions of the drug, the patient considers only the fraction γD of the price difference

. For the choice between the two versions of the drug, the patient considers only the fraction γD of the price difference  .14

.14

In country S, the consumer indifferent between b and not purchasing is given by  , resp.

, resp.  .

.

2.2 Indemnity insurance

(6)

(6)If parallel trade is not allowed, the consumer indifferent between b and not purchasing is given by  . Under parallel trade, the consumer indifferent between b and β is given by

. Under parallel trade, the consumer indifferent between b and β is given by  . For the choice between the two versions of the drug, consumers consider the full price difference

. For the choice between the two versions of the drug, consumers consider the full price difference  .15

.15

In country S, the consumer indifferent between b and not purchasing is given by  , resp.

, resp.

2.3 No parallel trade

First consider the case of no parallel trade. Both pricing decisions by the manufacturer—the drug price in country D and the wholesale price w—are independent.

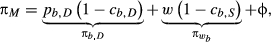

(7)

(7) the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales in S, and ϕ the fixed fee.

the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales in S, and ϕ the fixed fee. (8)

(8)In D, the manufacturer M sets drug price  to maximise (7). In S, the intermediary I sets drug price

to maximise (7). In S, the intermediary I sets drug price  to maximise (8).

to maximise (8).

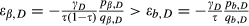

(9)

(9)Drug prices only depend on the cost-sharing system in the respective country. Under coinsurance, effective prices for consumers are equivalent to prices without insurance coverage. The effect of reimbursement by health insurance is completely appropriated by the manufacturer. Price differences result from differences in coinsurance rates.

Under indemnity insurance, effective prices are lower than prices without insurance. The effect of reimbursement benefits both the manufacturer (higher market prices than without insurance) and patients (lower effective prices than without insurance). Price differences occur, when reimbursement differs across countries.

2.4 Parallel trade

If parallel trade is allowed, the manufacturer's pricing decisions are no longer independent. A low wholesale price induces competition from parallel imports in D. Increasing the wholesale price in response creates a double-marginalisation effect in S. Consequently, the choice of the wholesale price reflects the trade-off between the double-marginalisation effect in S and intensified competition from parallel trade in D.

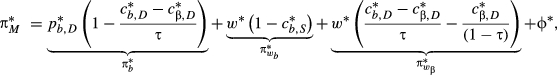

(10)

(10) denotes the profit from direct sale in D,

denotes the profit from direct sale in D,  the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales in S,

the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales in S,  the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales as parallel imports in D, and ϕ∗ the fixed fee.

the wholesale profit from the intermediary's sales as parallel imports in D, and ϕ∗ the fixed fee. (11)

(11) denotes the profit from sales in S and

denotes the profit from sales in S and  the profit from sales as parallel imports in D.

the profit from sales as parallel imports in D.In D, the manufacturer M maximises (10), which yields the best response function  . The intermediary maximises

. The intermediary maximises  , which yields the best response function

, which yields the best response function  . Equilibrium prices are

. Equilibrium prices are  and

and  .

.

In S, the intermediary maximises  , resulting in the price

, resulting in the price  . As

. As  increases in w∗,

increases in w∗,  higher under parallel trade if w∗ > 0.

higher under parallel trade if w∗ > 0.

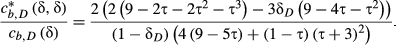

(12)

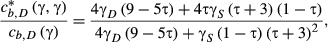

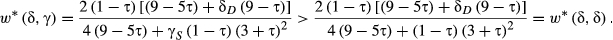

(12) and maximising with respect to w∗ gives the wholesale price

and maximising with respect to w∗ gives the wholesale price  .

.Under no parallel trade, the manufacturer sets the wholesale price equal to marginal cost, that is, w = 0, to avoid the double-marginalisation problem. Parallel trade makes the manufacturer raise the wholesale price to limit competition from parallel trade in country D. The optimal wholesale price reflects the trade-off between the double-marginalisation problem in S and competition in D. The wholesale price depends on cost-sharing systems in both countries and similarly, prices and quantities also do. Drug prices and quantities can be found in Appendix B.

3 THE EFFECT OF PARALLEL TRADE ON HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS

If parallel trade is allowed, the manufacturer raises the wholesale price to limit competition from parallel trade. In the source country, this creates a double-marginalisation effect with a higher drug price and a lower quantity. In the destination country, parallel trade generates a competition effect with lower drug prices and a higher quantity. A competition effect with price reductions is in line with the findings of West and Mahon (2003), Enemark et al. (2006), Granlund and Köksal (2011), and Duso et al. (2014).

The direct link between these price changes and the consequences for public healthcare systems is the cost-sharing system. The copayment mechanism determines, whether and to what extent consumers in the destination country benefit from price decreases and whether and to what extent consumers in the source country are exposed to price increases. Also, the reimbursement mechanism determines the consequences of parallel trade for public health expenditure.

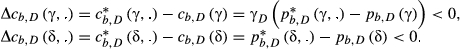

3.1 Changes in copayments and public health expenditure in the destination country

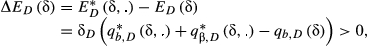

Proposition 1 summarises the effects of parallel trade on consumer copayments and public health expenditure in the destination country D.

Proposition 1.In the destination country D, lower drug prices under parallel trade decrease copayments under both cost-sharing systems. Suppose that drug prices under no parallel trade are identical under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Then savings for consumers are higher under indemnity insurance, independent of the cost-sharing system in the source country S. Parallel trade generates savings for health insurance only under coinsurance, under indemnity insurance, health expenditure is higher than under no parallel trade.

For analytical details, see Appendix C.

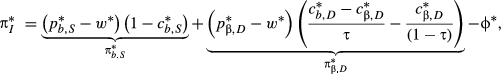

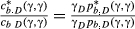

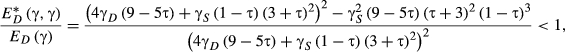

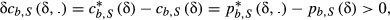

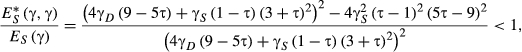

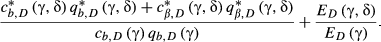

(13)

(13) and

and  , resp. This is, consumers benefit from parallel trade independent of the cost-sharing system. This result of savings for patients is consistent with the findings of West and Mahon (2003) and Enemark et al. (2006).

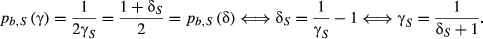

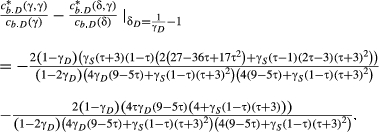

, resp. This is, consumers benefit from parallel trade independent of the cost-sharing system. This result of savings for patients is consistent with the findings of West and Mahon (2003) and Enemark et al. (2006).Which cost-sharing system creates higher savings, is determined by two factors: first, there is a direct impact of the cost-sharing system for a given wholesale price. Under indemnity insurance, consumers benefit from the full price decrease. Under coinsurance, only fraction γD of the price decrease is passed on to consumers. Second, the wholesale price drives the intensity of competition, as it limits the intermediary undercutting the manufacturer's price. These two factors are interdependent, as the wholesale price also depends on the degree of competition in the destination country.

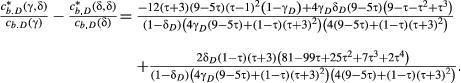

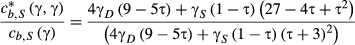

Accordingly, for a comparison of copayment changes under coinsurance and indemnity insurance, cost-sharing systems in both countries are important.

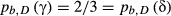

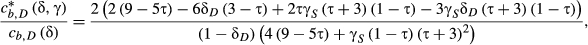

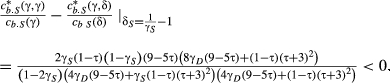

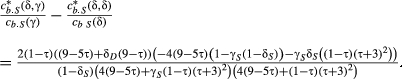

(14)

(14)Identical drug prices under both cost-sharing instruments do not imply identical copayments under coinsurance and indemnity insurance due to the different insurance effects.17 Assuming identical copayments for both cost-sharing systems under no parallel trade would involve no reimbursement under indemnity insurance due to the insurance absorbing effect of coinsurance under no parallel trade, see Appendix D. Also, assuming identical quantities under both cost-sharing systems under no parallel trade is subject to the same limitation.

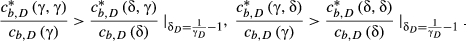

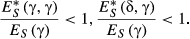

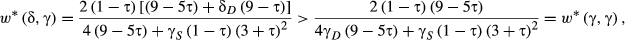

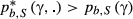

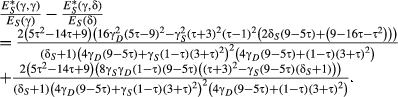

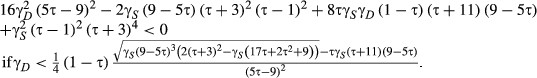

(15)

(15)No matter whether coinsurance or indemnity insurance is applied in S, the wholesale price is higher under indemnity insurance in D ( ,

,  resp.). This is, the higher intensity of competition under indemnity insurance induces the manufacturer to raise the wholesale price more than under coinsurance. In total, the impact of the full price difference accruing to consumers exceeds the effect of the higher wholesale price and consumer copayments are reduced more under indemnity insurance. The higher intensity of competition under indemnity insurance is similar to the finding of higher price reductions under reference pricing than under coinsurance by Köksal (2009).

resp.). This is, the higher intensity of competition under indemnity insurance induces the manufacturer to raise the wholesale price more than under coinsurance. In total, the impact of the full price difference accruing to consumers exceeds the effect of the higher wholesale price and consumer copayments are reduced more under indemnity insurance. The higher intensity of competition under indemnity insurance is similar to the finding of higher price reductions under reference pricing than under coinsurance by Köksal (2009).

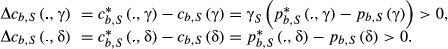

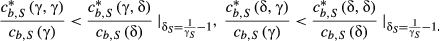

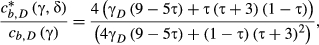

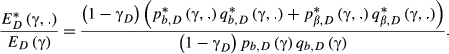

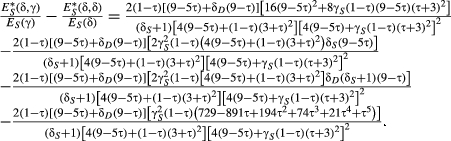

The competition effect generated by parallel trade has an ambiguous impact on total expenditure. Lower prices decrease expenditure, higher quantities increase expenditure. Whether parallel trade results in reductions in public health expenditure, depends on the cost-sharing system. Only if reimbursement is linked to drug prices, lower prices under parallel trade benefit health insurance.

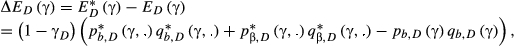

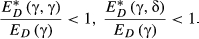

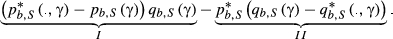

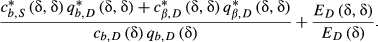

(16)

(16) (17)

(17)The negative part I of the decomposition shows the expenditure-decreasing effect from a lower price, while ignoring changes in quantity. The positive parts II and III of the decomposition indicate the expenditure-increasing effect of a higher quantity being sold and hence reimbursed under parallel trade. Due to lower prices, more is sold of the locally sourced version (part II) and of the parallel import (part III). This result of savings for health insurance is in line with the findings of West and Mahon (2003) and Enemark et al. (2006).

(18)

(18) (19)

(19)

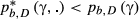

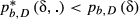

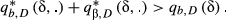

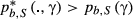

3.2 Changes in copayments and public health expenditure in the source country

Comparing the consequences of parallel trade for consumer copayments and public health expenditure in the source country yields the following proposition:

Proposition Proposition 2.In the source country S, a higher price under parallel trade increases copayments under both cost-sharing systems. Suppose that drug prices under no parallel trade are identical under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Then additional expenses for consumers are lower under coinsurance, independent of the cost-sharing system in the destination country D. Savings for health insurance from parallel trade are higher under indemnity insurance, regardless of the cost-sharing system in the destination country.

For analytical details, see Appendix C.

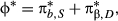

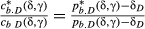

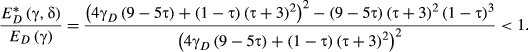

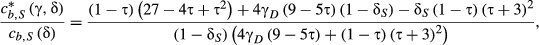

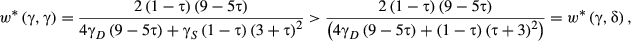

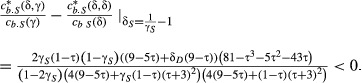

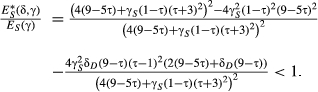

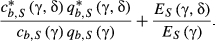

(20)

(20) and

and  , resp. Thus, consumers lose from parallel trade independent of the cost-sharing system.

, resp. Thus, consumers lose from parallel trade independent of the cost-sharing system.Under which cost-sharing system the additional expense is higher, is again determined by the direct impact of the cost-sharing system for a given drug price and price changes resulting from the increase in the wholesale price.

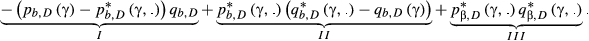

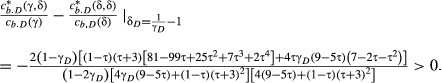

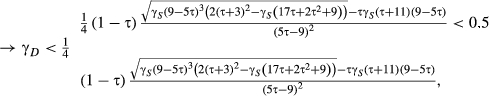

(21)

(21)Again, this standard of comparison assumes high coinsurance rates due to the positive copayment condition, see Appendix C.

(22)

(22)Although the wholesale price is higher under coinsurance ( ,

,  ), the direct effect of coinsurance insulating consumers from part of the price increases dominates and copayments increase less under coinsurance.

), the direct effect of coinsurance insulating consumers from part of the price increases dominates and copayments increase less under coinsurance.

The double-marginalisation effect induced by parallel trade has an ambiguous impact on total expenditure and public health expenditure. The higher drug price tends to increase expenditure, the lower quantity contributes to a reduction in expenditure.

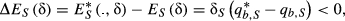

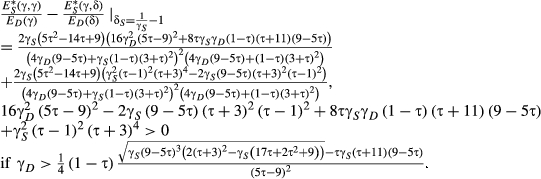

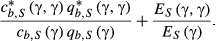

(23)

(23) (24)

(24)The positive part I of the decomposition shows the expenditure-increasing effect of a higher drug price, while neglecting changes in quantity. The negative part II reflects the reduction in expenditure due to the lower quantity sold and reimbursed under parallel trade.

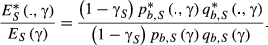

(25)

(25) (26)

(26) . Since reimbursement is not linked to drug prices, the drug price increase does not give rise to an expenditure-increasing effect. Instead, the decrease in quantity unambiguously decreases public health expenditure.

. Since reimbursement is not linked to drug prices, the drug price increase does not give rise to an expenditure-increasing effect. Instead, the decrease in quantity unambiguously decreases public health expenditure. (27)

(27)Under indemnity insurance, the drug price increase under parallel trade has no expenditure-increasing effect and expenditure is decreased by more.

3.3 Total changes

In both destination and source country, there is a conflict between lower copayments and savings for health insurance. This subsection considers total changes in expenditure, both private expenditure (sum of all copayments) and public expenditure (reimbursed part).

For the comparison, I assume identical drug prices under no parallel trade. This allows only for numerical results, see Appendix E.

In both countries, the total change in expenditure is negative, independent of the cost-sharing system. Parallel trade generates net savings. The level of the copayment determines, under which cost-sharing system savings are higher. In the destination country, total savings are higher under indemnity insurance for a sufficiently low copayment and higher under coinsurance for a higher copayment. In the source country, total savings are higher under coinsurance for a sufficiently low copayment and higher under indemnity insurance for a higher copayment.

As parallel trade generates total savings under both cost-sharing systems, the conflict between savings for consumers and savings health insurance could be resolved via transfers. But this might pose additional problems: Transfers from patients to health insurance via higher premiums or taxes may raise distributive concerns, as they might worsen access to pharmaceuticals. Transfers from health insurance to patients in the form of subsidies may aggravate the moral hazard problem.

If transfers are not possible, the choice of the cost-sharing system boils down to a decision between minimising public expenditure and limiting financial exposure of patients.

4 DISCUSSION

This section addresses assumptions of the model and their implications for the analysis.

4.1 Perceived quality difference

The model assumes that the parallel import is perceived as of lower quality compared to the locally sourced version. This is in line with the observation of higher prices for locally sourced versions, which cannot be explained by higher marginal cost (and by assuming homogenous products).

If the parallel import and the locally sourced version were considered as homogeneous products, for example, because consumers disregarded the differences in appearance or were familiar with the parallel import from previous purchases and intake, the competitive effect of parallel trade in the destination country would be much stronger. In response, the manufacturer would increase the wholesale price by more to limit competition from parallel trade in the destination country, thereby reinforcing the double-marginalisation effect in the source country. This is, also for homogeneous products, parallel trade would result in a price-decreasing competition effect in the destination country of the parallel import and a price-increasing double-marginalisation effect in the source country. Accordingly, the effect of cost-sharing systems in this case can be expected to be similar to the case of vertical product differentiation.

4.2 Wholesale price regulation

In many European countries, wholesale prices for pharmaceuticals are regulated. This paper abstracts from this, as it focuses on the effect attributed to parallel trade only.

If a regulated wholesale price was assumed for the source country, the manufacturer would not be able to adjust the wholesale price in response to parallel trade. Accordingly, he could not limit competition from parallel trade in the destination country by increasing the intermediary's cost. Maybe he would try to affect the perception of the parallel import, as suggested by Kyle (2011). Moreover, the manufacturer might limit supply to the source country in response to parallel trade. The effect of parallel trade for the source country then would be similar as under free wholesale price setting, it would result in shortages. For the destination country, parallel trade results in a competition effect, independent of wholesale price setting being regulated or free. Accordingly, the effect of cost-sharing systems in this case can be expected to be similar.

5 CONCLUSION

This paper studied the effect of parallel trade on healthcare systems, suggesting a strong link between the consequences of parallel trade and cost-sharing systems.

In the destination country, savings for patients from parallel trade occur under both systems, but are relatively higher under indemnity insurance. However, savings for health insurance from parallel trade occur only under coinsurance, as indemnity insurance fails to establish a link between the reimbursement and drug prices. Consequently, maximising savings for patients by adopting indemnity insurance occurs at expense of increasing public health expenditure. Applying coinsurance instead shifts savings from patients to health insurance partially. This makes coinsurance a more attractive cost-sharing mechanism for health insurance; the failure to link prices to expenditure may constitute a reason why indemnity insurance is considered to be inappropriate as a cost-sharing instrument. Indemnity insurance as cost-sharing system cannot be found in pure form in any member state of the European Union. But applied instruments such as deductibles and reference pricing share a similar mechanism.

In the source country, the drug price increase results in additional expenses for consumers under parallel trade, but the associated reduction in quantity consumed benefits health insurance. Again a conflict between minimising negative consequences from parallel trade for patients and maximising positive consequences for health insurance emerges. Consequently, also the distributive effects of parallel trade in the source country are determined by the cost-sharing scheme.

Accordingly, if minimising public health expenditure is the dominant health policy objective, coinsurance should be the cost-sharing instrument of choice in the destination country and indemnity insurance in the source country. If minimising financial exposure of patients and maximising access to pharmaceuticals is the prevailing health policy objective, indemnity insurance is the appropriate cost-sharing scheme in the destination country and coinsurance in the source country. With respect to the distribution of savings on patients and health insurance it may be noted that savings for health insurance may be characterised as indirect savings for patients, as lower expenditure for health insurance may translate to lower premiums or taxes (Enemark et al., 2006).

As parallel trade generates total savings under both cost-sharing systems, the conflict between savings for consumers and savings health insurance could be resolved via transfers between consumers and health insurance. But this might pose additional problems such as distributive concerns for higher premiums or taxes or an aggravated moral hazard problem for subsidies to consumers. If transfers are not possible, the choice of the cost-sharing system boils down to a decision between the minimising public expenditure and limiting financial exposure of patients.

The literature on the effect of pharmaceutical parallel trade on health expenditure is somewhat inconclusive. This paper contributes to this literature by focusing on the link between cost-sharing systems and parallel trade. This paper makes use of a simplified model, which abstracts from some characteristics in real-world pharmaceutical markets to highlight the impact of parallel trade on savings for healthcare systems. The stylised nature of the model may explain differences between my results and some results in the literature.

In line with my findings, Enemark et al. (2006) highlight the incentive for patients to decide in favour of lower priced drugs and thus the role of the cost-sharing system in generating savings from parallel imports. This is consistent with the findings of the game-theoretic model and empirical analysis conducted by Vandoros and Kanavos (2014). Also Jelovac and Bordoy (2005) emphasise the importance of cost-sharing systems for the effect of parallel trade. While in their model, differences in cost-sharing systems may be accountable for both the occurrence of parallel trade and its consequences, in this paper, the occurrence of parallel trade depends only on the vertical control structure, while the cost-sharing determines the consequences of parallel trade.

The empirical literature on the effect of parallel trade in pharmaceutical markets is ambiguous. The unclear empirical results may stem from different methodologies (Duso et al., 2014), the analysis of different countries with different pharmaceutical regulations, different time-periods as well as the analysis of different molecules (Enemark et al., 2006).

With respect to price reductions in the destination country, the results of this paper are mainly in line with the findings of West and Mahon (2003), Enemark et al. (2006), Granlund and Köksal (2011), and Duso et al. (2014). Kanavos et al. (2004), Kanavos and Vandoros (2010), and Vandoros and Kanavos (2014) however, find an upward price convergence. Limited volumes of parallel imports may account for this effect (Enemark et al., 2006). In the empirical literature, especially, West and Mahon (2003), Enemark et al. (2006), and Kanavos et al. (2004), the effect of parallel imports on savings is closely linked to price decreases. This paper has shown that even if prices decrease, this does not always translate to savings (in case of indemnity insurance in the destination country). In addition, this paper shows that also for price decreases, the magnitude of healthcare savings depends on the cost-sharing system. Moreover, this paper complements the existing literature by also studying the effect of parallel trade for changes in expenditure in the source country of parallel imports.

Kyle (2011) explains the lacking of empirical price convergence by strategic modifications of the product such as different dosage forms for different countries. The detailed structure of firms' portfolio with regard to dosage forms as well as other creative adaptive behaviour is beyond the scope of the present paper. The different results in Kyle (2011) and this paper do not primarily contradict each other. But both papers point at different adjustments originating from the competitive pressure of parallel imports. Differences in the appearance and/or dosage of original and parallel imported drugs could be captured in my model by the degree of vertical differentiation τ. As these differences are also chosen by producers, further research could focus on τ as a strategic variable for producers.

Due to the simplified model of this paper, it cannot capture the effect of complex (and mainly country-specific) price regulations such as mandatory discounts or the clawback mechanism between pharmacies and health insurance described in Kanavos and Costa-Font (2005). Studying the complex effects of such country-specific regulation has to be taken into account in interpreting empirical findings, but is well beyond the scope of this paper.

In the European Union, parallel trade generates a “single market” for pharmaceuticals. Health policy, including the general organisation of healthcare systems as well as cost-sharing systems, is in the national competence of member states. A harmonisation of healthcare systems with respect to cost-sharing systems may not be advisable, as this paper illustrates. Under parallel trade reimbursement systems have different effects in source and destination countries of parallel imports. Thus, a harmonisation of reimbursement systems would result in welfare losses in source and/or destination countries.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Horst Raff, Annika Herr, and Jan S. Voßwinkel for helpful comments and suggestions.

Notes

to

to  . The price elasticity of demand of the parallel import is higher than for the locally sourced version:

. The price elasticity of demand of the parallel import is higher than for the locally sourced version:  .

.

under no parallel trade and

under no parallel trade and  . Again, parallel trade increases the price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of the parallel import is higher than for the locally sourced version

. Again, parallel trade increases the price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of the parallel import is higher than for the locally sourced version  .

.

). Then, under coinsurance, consumers pay

). Then, under coinsurance, consumers pay  and under indemnity insurance

and under indemnity insurance  .

.

APPENDIX A

DRUG PRICES AND QUANTITIES UNDER NO PARALLEL TRADE

Drug prices in both countries are given as:

D↓ , S |

Coinsurance | Indemnity insurance |

|---|---|---|

| Coinsurance |   |

|

| Indemnity insurance |   |

|

Equilibrium quantities are:

D↓ , S |

Coinsurance | Indemnity insurance |

|---|---|---|

| Coinsurance |   |

|

| Indemnity insurance |   |

|

APPENDIX B

DRUG PRICES AND QUANTITIES UNDER PARALLEL TRADE

The wholesale price is:

D↓ , S |

Coinsurance | Indemnity insurance |

|---|---|---|

| Coinsurance |

|

|

| Indemnity insurance |

|

|

Drug prices in both countries are:

D↓ , S |

Coinsurance |

|---|---|

| Coinsurance |

|

| Indemnity insurance |

|

D↓ , S |

Indemnity insurance |

|---|---|

| Coinsurance |  |

| Indemnity insurance |  |

The cost-sharing system's parameters in parentheses denote the cost-sharing in D and S, resp., for example,  denotes the drug price in S, if D applies coinsurance and S indemnity insurance.

denotes the drug price in S, if D applies coinsurance and S indemnity insurance.

Equilibrium quantities are given as:

| H, F | Coinsurance |

|---|---|

| Coinsurance |

|

| Indemnity insurance |

|

D↓ , S |

Indemnity insurance |

|---|---|

| Coinsurance |  |

| Indemnity insurance |  |

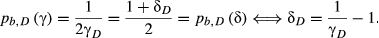

APPENDIX C

CHANGES IN COPAYMENTS AND PUBLIC HEALTH EXPENDITURE

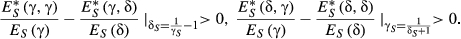

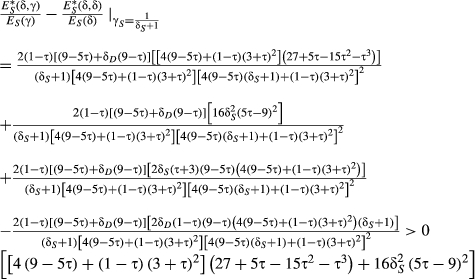

C.1 Destination country

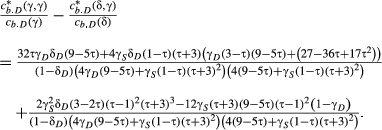

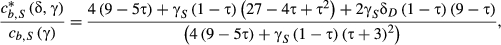

. The relative copayment change in the destination country D under indemnity insurance is:

. The relative copayment change in the destination country D under indemnity insurance is:

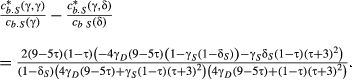

. The difference between relative copayment changes then is:

. The difference between relative copayment changes then is:

Identical drug prices under segmented markets as standard of comparison imply coinsurance rates of  or γD > 0.6, depending on the cost-sharing system in the source country. As consumers are required to co-pay a positive amount, the reimbursement amount δD is restricted to

or γD > 0.6, depending on the cost-sharing system in the source country. As consumers are required to co-pay a positive amount, the reimbursement amount δD is restricted to  , with

, with  and

and  . This implies

. This implies  (a) for γ in S,

(a) for γ in S,  (b) for δ in S, with (a) ∈ (0.5, 1), (b) ∈ (0.6, 1). Also, for γD < γS (parallel trade from the low price to high price-country), (a) implies

(b) for δ in S, with (a) ∈ (0.5, 1), (b) ∈ (0.6, 1). Also, for γD < γS (parallel trade from the low price to high price-country), (a) implies  , which is only satisfied for high γS.

, which is only satisfied for high γS.

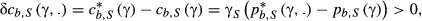

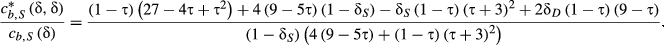

C.2 Source country

. Under indemnity insurance, the change in copayments in S is:

. Under indemnity insurance, the change in copayments in S is:

since  .

.

Similar to assuming identical drug prices in the destination country D implying high coinsurance rates, this standard of comparison for the source country requires rather high coinsurance rates due to the positive copayment condition under indemnity insurance. The reimbursement amount δS is restricted to  , with

, with  and

and  . This implies

. This implies  (a) for γ in D,

(a) for γ in D,  (b) for δ in D, with (a) ∈ (0.25, 0.5), (b) ∈ (0.375, 0.5). Admittedly, this also allows for rather moderate coinsurance rates, but this would correspond to restrictions on the degree of vertical product differentiation τ or the coinsurance rate in the destination country. The general case, without further restrictions, however, assumes high coinsurance rates.

(b) for δ in D, with (a) ∈ (0.25, 0.5), (b) ∈ (0.375, 0.5). Admittedly, this also allows for rather moderate coinsurance rates, but this would correspond to restrictions on the degree of vertical product differentiation τ or the coinsurance rate in the destination country. The general case, without further restrictions, however, assumes high coinsurance rates.

As a higher ratio of relative copayments implies higher price increases, this corresponds to copayments being increased less under coinsurance.

This is, copayments increase less under coinsurance.

APPENDIX D

IDENTICAL COPAYMENTS AS STANDARD OF COMPARISON

Under segmented markets, coinsurance has the same effect as no reimbursement (effective prices under coinsurance correspond to effective prices under no insurance). Assuming identical copayments then transfers this effect to indemnity insurance as well. But for coinsurance, the manufacturer is only able to absorb the insurance effect entirely under segmented markets. Under parallel trade, competition prevents it from doing so. Assuming identical copayments under segmented markets not only transfers this insurance-absorbance effect to the indemnity insurance scheme under segmented markets, but also to the indemnity insurance scheme under parallel trade, corresponding to assuming no reimbursement under indemnity insurance for both cases and thus comparing coinsurance with no insurance. This results in copayments decreasing always more under coinsurance, as coinsurance provides reimbursement, whereas indemnity insurance under this standard of comparison does not.

APPENDIX E

Total changes

Comparing total changes in expenditure—both private expenditure (sum of all copayments) and public expenditure (reimbursed part)—under coinsurance and indemnity insurance, I assume identical drug prices for both cost-sharing systems under segmented markets.

E.1 Destination country

Under both cost-sharing systems, the change in expenditure is negative, that is, savings are generated.

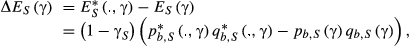

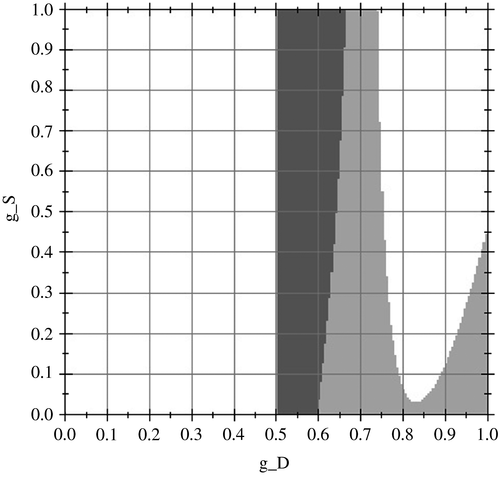

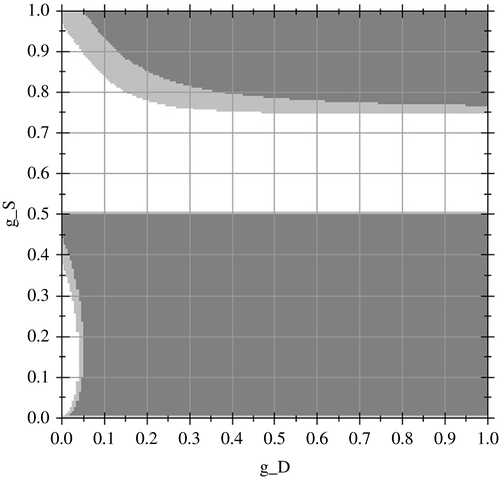

Figure A1 illustrates the comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for τ = 0.5. The abscissa shows the value for γD, and the ordinate shows the value for γS. In the white area, the change in total expenditure is higher under coinsurance; in the (darker) grey area, it is higher under indemnity insurance. In the light grey area, total changes are very similar under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Identical drug prices under segmented markets as standard of comparison imply coinsurance rates of γD > 0.5, see Appendix C.1. For 0.5 < γD ≲ 0.6, the total change in expenditure is higher under indemnity insurance; for γD ≳ 0.75, the total change in expenditure is higher under coinsurance.

The comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for other degrees of  is similar.

is similar.

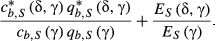

Under both cost-sharing systems, the change in expenditure is negative, that is, savings are generated.

Figure A2 illustrates the comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for τ = 0.5. The abscissa shows the value for γD, and the ordinate shows the value for γS. In the white area, the change in total expenditure is higher under coinsurance; in the (darker) grey area, it is higher under indemnity insurance. In the light grey, area total changes are very similar under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Identical drug prices under segmented markets as standard of comparison imply coinsurance rates of γD > 0.6, see Appendix C.1. For 0.6 γD ≲ 0.65, the total change in expenditure is higher under indemnity insurance; for γD ≳ 0.7, the total change in expenditure is higher under coinsurance.

The comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for other degrees of  is similar.

is similar.

E.2 Source country

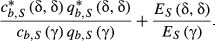

Under both cost-sharing systems, the change in expenditure is negative, that is, savings are generated.

Figure A3 illustrates the comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for τ = 0.5. The abscissa shows the value for γD, and the ordinate shows the value for γS. In the white area, the change in total expenditure is higher under coinsurance; in the (darker) grey area, it is higher under indemnity insurance. In the light grey area, total changes are very similar under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Identical drug prices under segmented markets as standard of comparison imply coinsurance rates of γS > 0.5, see Appendix C.2. For 0.5 γD ≲ 0.75 and γD > 0.5, the total change in expenditure is higher under coinsurance; for γS ≳ 0.75 and γD > 0.5, the total change in expenditure is higher under indemnity insurance.

The comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for other degrees of  is similar.

is similar.

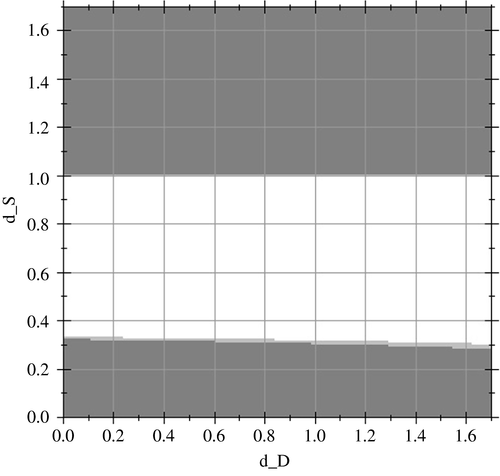

Under both cost-sharing systems, the change in expenditure is negative, that is, savings are generated.

Figure A4 illustrates the comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for τ = 0.5. The abscissa shows the value for δD, and the ordinate shows the value for δS. In the white area, the change in total expenditure is higher under coinsurance; in the (darker) grey area, it is higher under indemnity insurance. In the light grey area, total changes are very similar under coinsurance and indemnity insurance. Due to the positive copayment condition under indemnity insurance, the reimbursement amounted is restricted to δD < 0.65 and δS < 1.6, see Appendix C.2. For 1.6 > δS ≳1 and δS ≲ 1, the total change in expenditure is higher under coinsurance; for γS ≳ 0.75 and γD > 0.5, the total change in expenditure is higher under indemnity insurance.

The comparison of total changes in expenditure under coinsurance and indemnity for other degrees of  is similar.

is similar.