Manufacturing servitisation and duration of exports in China

[Correction added on 14 February 2018 after first online publication: The funding information was previously missed and has been added in this current version.]

Abstract

In recent years, manufacturing servitisation has become a growing characteristic of global firms. Firms develop their service factors, to realise more values and increase their international competitiveness. China, as an important manufacturing centre of the world, has abundant manufacturers seeking for getting more involved in the international market. This paper makes use of detailed customs data and firm-level data from China, to find how the servitisation in China affects the export durations of Chinese manufacturers. The results demonstrate that manufacturing servitisation input in China contributes to export performance. The service factors have become the important production factors in Chinese manufacturing enterprises. However, China is still at the primary stage of manufacturing servitisation, and Chinese manufacturing enterprises should pay more attention to the whole value chain and seek the transformation from a pure manufacturing enterprise to a service manufacturing enterprise.

1 INTRODUCTION

In recent years, servitisation, which is recognised as the process of creating additional value through adding more services to products, has become a growing characteristic of global firms. Along with the trend of transformation from an industrial economy to a service economy, not only service firms but also manufacturing firms have been more prone to increase their values and profits through the development of service. Neely (2009) examines data for more than 10,000 manufacturing firms around the world and finds that about 30% of manufacturing firms also offer services. Moreover, Neely (2009) notes that the range of services offered by manufacturing firms is varied and the extent of servitisation is significantly different in different countries.

According to the theory of comparative advantage, which is regarded as a fundamental starting point for international trade research, comparative advantage is derived from technological and factor endowments. Making use of its comparative advantage, a country tends to specialise in the production and export of goods and services which are produced more efficiently, in other words with more abundant resource supply and at lower cost. The servitisation of a firm is aiming to add services to its products, in other words to add additional value to the products. Heskett, Sasser, and Schlesinger (1997) argue that servitisation is considered as a sustainable source of comparative advantage and allows for greater differentiation. Firms in developed countries make use of their advantages in R&D, services and marketing, to dominate the global production network and global value chain. Some world-famous and top-level manufacturers, such as GE, Philips and IBM, increasingly focus on innovations of service patterns, to improve their competitiveness.

As an important manufacturing centre of the world, China has played an increasingly important role in the global value chain. In recent years, manufacturing firms in China are seeking to add more value through servitisation. For example, one of the most famous manufacturing firms in China, Haier, has increased its international competitiveness by establishing a whole new service pattern called “whole life cycle,”1 which provides a total solution from initial research and design to production, marketing and aftermarket.

However, compared with developed countries, the extent of manufacturing servitisation in China is still at a relatively low level. According to Neely (2009), less than 1% of Chinese manufacturers had servitised in 2007, compared with 58% of manufacturers in the United States. The data from the OECD and the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China further demonstrate that the development of manufacturing servitisation in China is still at a relative lower level and lags behind that of other countries. In developed countries, the service industry usually contributes about 70% of their GDP, and the manufacturing service industry takes up at most 70% of the whole service industry, which is the so-called Double 70% phenomenon. However, the service industry in China contributes less than 50% of the GDP. The lower level and the slower speed of development of the servitisation lead to a lower stage of the Chinese manufacturing industry in the global value chain.

In each stage of the industry chain, manufacturing servitisation may play important roles in different aspects. From upstream to downstream of the industry chain, manufacturing servitisation can input more on market survey and R&D, decrease trade costs and improve the after-sales services, to produce more heterogeneous products and foster the competitiveness in the international market. Heterogeneous products are generally difficult to be imitated and substituted. Meanwhile, once possessing a sufficient competitiveness, the enterprise may be more confident in participating in the international market and have a greater ability to survive in the international competition. Servitisation is a method to increase the differentiation of manufacturing products.

The duration of trade relationships has aroused the interests of trade researchers since the year 2006. There is a series of researches which argue that short-lived trade relations exist in both developed and developing countries and sustained international trade relations are the driving force of export success (Besedeš & Prusa, 2006a, 2011; Brenton & Newfarmer, 2007; Brenton, Saborowski, & Uexkullb, 2010; Nitsch, 2009). Besedeš and Prusa (2006b) examine the extent to which product differentiation affects the duration of US import trade relationships and find that differentiated products have relatively lower hazard rates. Servitisation can increase the differentiation of manufacturing products. Thus, the manufacturing enterprise can provide differentiated products in the export market through the process of servitisation and further have longer trade duration for higher level servitisation products.

China's government has unveiled a “Made in China 2025” strategy of promoting China to be a world manufacturing power. In this 10-year action plan, promoting service-oriented manufacturing and manufacturing-related service industries has been one of the key tasks.2 Chinese exporting firms can maintain trade stability and may further contribute to upgrade the value chain of the manufacturing industry by developing servitisation. Furthermore, both manufacturing servitisation and trade duration are hotspot research topics, while the research on the relationship between them is scarce. Therefore, this paper makes use of detailed customs data and firm-level data from China to analyse the relationship between manufacturing servitisation and trade duration. This paper aims to answer the question of whether the development of servitisation promotes the export survival of Chinese manufacturing enterprise in the foreign market.

This paper contributes new empirical evidence to the emerging and developing topic, trade duration, and first explores the relationship between trade duration and manufacturing servitisation. Much of the previous literature studies a series of determinants of firms’ export duration, such as intermediate inputs (López, 2006), product differentiation (Besedeš & Prusa, 2006b), export growth (Julian, Giovanni, & Ricardo, 2013), the prevalence of neighbouring firms (Fernandes & Tang, 2014), export promotion agencies (Daniel, Marcelo, & Lucas, 2015) and investment (Rho & Rodrigue, 2016). However, there is little research on how manufacturing servitisation affects the survival of exporters. This paper does enrich the existing literature about factors on export duration.

Moreover, this paper explores a unique data set that links the World Input-Output Database (WIOD) to the Chinese Customs Database of Imports and Exports and the Chinese Industrial Enterprises Database, and enriches the firm-level empirical results to the research on Chinese exports. Besides the baseline results, the richness of the data allows us to confirm that the impact of manufacturing servitisation on export duration of exporters is being driven by product differentiation and R&D. In addition, we take a step forward to check the heterogeneous effects by considering different types of firm ownership and trade pattern. This paper generally reveals some interesting and specific characteristics about Chinese trade and exporters and also shows that there is great potential for further researches about topics about Chinese trade.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature. Section 3 describes the data sets used in the analysis and the processing of data. Section 4 briefly introduces the current status of manufacturing servitisation and export duration of China. Section 5 provides the empirical strategy and results, and Section 6 concludes.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Vandermerwe and Rada (1988) coined the term “servitisation,” which means a process that allows many industries and firms to create additional value to core corporation through offering more services. By adopting this market strategy, companies can build a new or stronger relationship to their customers.

Later, many researchers (Baines, Lightfoot, Benedettini, & Kay, 2009; Desmet, Dierdonck, Gemmel, Looy, & Serneels, 1998; Reiskin, White, Kautfman, & Votta, 2000; Ren & Gregory, 2007; Slack, 2005; White, Stoughton, & Feng, 1999) propose a series of definitions which can be summarised as follows: servitisation is a transformation process to increase the values of all participators in the manufacturing value chain, through the participation of customers, service orientation and the collaboration between firms. The process is aimed to satisfy customers’ needs, enhance the firm's performance and achieve competitive advantages.

Some papers provide clear and convincing evidence that manufacturers have moved dramatically into services (Davies, Brady, & Hobday, 2006; Neely, 2009; Oliva & Kallenberg, 2003; Slack, 2005; Vandermerwe & Rada, 1988; Wise & Baumgartner, 1999), and “servitization is happening in almost all industries on a global scale” (Vandermerwe & Rada, 1988). Not only service companies but also manufacturing companies are engaged in this servitisation trend. Schmenner (2009) suggests that ever since the 1850s, manufacturers have been seeking to expand into services to reduce their reliance on distributors and increase the strength of their customer relationships. This literature reflects a growing interest in this topic by academia, business and government, much of which is based on a belief that a move towards servitisation is a means to create additional value-adding capabilities for traditional manufacturers by adding services or integrating services in their core products.

The researchers argue that this kind of business generation shift is caused by deregulation, improvement of technology, globalisation and intensified completion. These integrated product-service offerings are distinctive, long-lived and easier to defend from competition based in lower cost economies. Servitisation should be considered at the level of one company's strategy and planning, rather than as a separate category. Servitisation can prompt the competitiveness of an enterprise in the international market and thus foster long-lived trade relationship in all stages of the industry chain.

In the upper stream of the industry chain, manufacturing servitisation can focus more on establishing the efficient enterprise organisation, providing abundant human capital and improving the system of market survey and R&D (Grubel & Walker, 1989; Yuan, Geng, & Zhang, 2007). An efficient organisational structure and abundant human capital can increase the competitiveness of an enterprise, while a creative and well-running R&D system may help an enterprise to create, design and manufacture more heterogeneous products. This competitiveness allows the enterprise to enter, participate and stay in the international market more easily. Heterogeneous products have attributes that are significantly different from each other and difficult to be imitated and substituted. Once trade relations of heterogeneous products begin, it is more prone to keep longer and stable, as argued by Besedeš and Prusa (2006b).

In the middle stream of the industry chain, manufacturing servitisation can promote the core competitiveness of an enterprise by decreasing trade costs and developing the specialisation of labour division (Francois, 1990; Jones & Kierzkowski, 1988). With the increase in the enterprise's competitiveness, the enterprise may have more confidence and more ability on participating in the export market.

In the downstream of the industry chain, manufacturing servitisation can improve the level of transportation and after-sales services (Oliva & Kallenberg, 2003). Through the development of supporting services, an enterprise can make products more adaptive to local markets and more familiar to markets, and further increase brand awareness and custom recognition. In addition, the strategy of product heterogeneity also fosters the extension of the enterprise from the traditional manufacturing production process to the downstream of value chain (Görg, Kneller, & Muraközy, 2012). All of the above make trade relationships more stable and durable.

Traditional trade theories argue that international trade relationships are relatively long-lived and robust. The factor proportions theory, for instance, argues that once a country usually has a relative stable comparative advantage in a particular product, which means that once two countries begin to trade the particular product, due to the fact that endowments are rarely changed in a short time, the established relationships will last. The Melitz (2003) model also suggests that once a trade relationship has been established, it is robust.

However, recent empirical results from analysing detailed trade data point out that the short-lived trade relationship widely exists in the real world. Besedeš and Prusa (2006a) first use US data to find that the duration of US import relations is very short. Nitsch (2009) and Hess and Persson (2010), respectively, find the international trade relations are also short-lived in Europe by making use of international trade data from Germany and 15 European countries. Besedeš and Prusa (2011) find the median of trade duration is 1–2 years of 46 countries from six districts (Asia, Caribbean, Central America, South America, North America, Africa). They also point out the significant difference among countries: developed countries and successful developing countries have longer surviving trade relationships than other countries. Nevertheless, only one-quarter of trade relations in successful exporters exceed 5 years. Besedeš and Blyde (2010) use SITC 4-digit trade data from Latin America to draw the similar conclusions that short-lived trade duration exists in Latin America and that the trade survival rate is significantly lower than in America, Europe and Eastern Asia by, respectively, 11%, 5% and 6%. Brenton et al. (2010) use disaggregated 1985–2005 trade data from 82 developing countries to study trade duration and find only one-third duration spells are longer than 5 years. Moreover, a large number of researchers find that incumbent and sustained trade relations have more contribution to a country's export success (Brenton & Newfarmer, 2007; Brenton et al., 2010). Meanwhile, the literature has put in the effort to explain short-lived trade duration and finds that economic size, cultural proximity and geographic ties are important determinants of trade survival (Besedeš & Prusa, 2006a; Brenton et al., 2010; Nitsch, 2009).

For China, the research about trade duration increases dramatically. Shao (2011) uses HS 6-digit product-level trade data of China between 1995 and 2007 to study the duration of Chinese exports and finds that short-lived trade relations exist, with the median and mean value of 2.84 and 2 years. Initial trade value, the market scale of the destination of export, the type of commodity, unit value of commodities and the stability of the exchange rate have effects on the duration of Chinese export relations. He and Zhang (2011) use highly disaggregated trade data of Chinese agricultural products exporting to the United States from 1989 to 2008 and find that the mean duration of HS 10-digit agriculture products is 3.9 years and the median is 2 years.

With the development of firm-level trade theory and usage of firm-level trade data, a rich literature on the firm-level export activity and performance has emerged. Melitz (2003) first introduces the “heterogeneity of firms” into the Krugman (1980) trade model and argues that only firms with higher productivity choose to export to foreign countries, while Bernard, Eaton, Jensen, and Kortum (2003) extend the Ricardian model to a trade model which includes imperfect competition, differences in technological efficiency across producers and countries and heterogeneity of plants and draw the similar conclusion that only higher productivity countries choose to enter the export market by fitting the model to bilateral trade among the US and 46 major trade partners. Jensen and Musick (1996) analyse a sample of US manufacturing plants over 1987 and 1992 and divide all plants in the sample into the following four groups on the basis of whether or not they export and whether they are high-tech or low-tech. They find that exporting activities and advanced technology are independently and positively correlated with plant success, and successful plants are more prone to participating in exporting activities. Thomas and Narayanan (2012) use firm-level 1990–2009 data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) to analyse productivity heterogeneity and firm-level export market participation in the Indian manufacturing industry. This paper provides evidence that exporting firms are more productive than the non-exporting firms in India. Alvarez and Gustavo (2007) use 20 years of Chilean manufacturing plant-level data, and Shevtsova (2010) uses the firm-level data of Ukrainian manufacturing and service sectors in the period 2000–05 and draws the similar conclusion that a higher productivity is positively correlated with a higher presence in international markets.

In recent years, the literature using firm-level data to analyse the duration of trade relationships is emerging. Esteve-Pérez, Requena-Silventea, and Pallardó-López (2013) use firm-level trade data of Spain to analyse trade duration during the period 1997–2006. This paper finds that a typical firm–country exporting relationship has a median duration of 2 years, and if a firm has survived in the export market beyond 2 years, the exiting risk sharply declines. Meanwhile, this paper argues that a firm's heterogeneity is crucial to foster the survival in the export market. Lejour (2013) uses Dutch firm-level customs data from 2002 to 2008 and finds that the hazard rate of firm–country–product relations with new exporting firms or incumbent firms to new countries is ~15% lower. This paper also proposes the following results: EU membership decreases the hazard rate; trade relations with an initial export value of about 50,000 euro do not survive, while those with an initial value of 200,000 euro exist after a few years; and exports with homogeneous goods tend to have higher initial trade values and a lower hazard rate. Mao and Sheng (2013) use the higher disaggregated Chinese customs data and firm-level microdata from 1998 to 2007 to analyse the effects of trade liberation on export dynamics of Chinese enterprise. Chen, Li, and Zhou (2012) make use of the matching data of China's customs database and the Chinese industrial enterprise database during the period 2000–05 and find the average duration of trade by Chinese exporters is less than 2 years with a median of 3 years. Moreover, they argue that the prominent negative duration dependence and the influences of variables in the gravity model on the duration of exports are consistent with those on trade flows. Firm-level characteristics, regional features and ownership have remarkable influences on trade duration. Fernandes and Tang (2014) use transaction-level data for Chinese exporters over the period 2000–06 to find the evidence that learning from neighbours does affect new exporters’ performance. They apply trade survival in their theoretical model and empirical work and argue that neighbours’ export performance raises the firm's probability of entry, but lowers its postentry growth conditional on survival.

3 DATA

3.1 Data source

The data sets used mainly come from the following three databases: World Input-Output Database (WIOD),3 Chinese Industrial Enterprise database and Chinese Customs Database of Imports and Exports.

The main indicators—manufacturing servitisation input and servitisation output—are calculated using the data from the WIOD. WIOD is the public database that provides time series of world input–output tables for forty countries, covering the period 1995–2011 globally. In this analysis, input–output data from 2000 to 2006 are used to calculate the key indicators of servitisation input and servitisation output.

The Chinese Customs Database of Imports and Exports covers detailed Chinese import and export information of more than 12,000 kinds of trade commodities. The complete information about producing and marketing countries, barrier, units in operation, the region of use, quantity, trade value, corporation way of contact and others is included. Highly disaggregated customs data from this database during the period 2000–06 are used to constitute the enterprise–product–partner triplet.

The Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database is a detailed database which provides the detailed information about productivity, corporate structure, finance and other indicators of 210,000 enterprises, whose sales volumes are above 5,000,000 RMB annually from 1996 to 2006. This analysis makes use of such data from the year 2000 to 2006.

3.2 The matching strategy of databases

Due to the different statistical regimes of both Chinese data sets, it is important to properly match the Chinese Customs Database of Imports and Exports and the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database. The firm identification ID in the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database is different from the tax encoding ID used in the Chinese Customs Database of Imports and Exports. While there is no other single piece of information available in the two data sets which can uniquely identify an entrepreneur, there is additional information such as an entrepreneur's name, address, postcode or telephone number. Therefore, to merge the two data sets, we follow the detailed method used in Tian and Yu (2013) to implement the following two-step merge strategy, by making use of the original industrial enterprise data and customs data without the elimination of any enterprise.

First, 81,895 firms are matched using the name of the enterprise and year. In this step, year information is crucial. Because the same firm may have different names in different years, name information and year information should be used together to identify the same firm. Next, the postcode of a firm's postal address and the last seven digits of its telephone number are used to match the remaining firms which had not been matched in the first step. The logic behind using the last seven digits of the telephone numbers here is the following: suppose that a firm in the district with the same postcode uses the same telephone number. Due to the distinctions of telephone number digits in different areas of China and because some cities have added a first number to the former seven-digit telephone number, we use the last seven numbers to implement the matching process. In this step, the number of matched firms increases to 89,075. The sample of matched firms is larger than that in Tian and Yu (2013), who use an accounting standard to get 76,823 enterprises matched. Meanwhile, the sample has the same matching ratio with that in Chen et al. (2012).4

Moreover, due to the problems of deficiency and abnormity of indicators in the Chinese Industrial Enterprise Database, the full sample is filtered according to the following steps: (i) deleting the observations without the indicators of firm industrial output and average balance of net value of fixed assets; (ii) deleting the sample of firms which do not comply with the accounting standards—for example, total asset is less than current asset, total asset is less than yearly average balance of net value of fixed assets, or accumulated depreciation is less than current depreciation; and (iii) deleting the observations not satisfying the “above designated size” standard—for example, the number of employees is less than 30, prime operating revenue is less than 5 million RMB, or yearly average balance of net value of fixed assets is less than 10 million RMB, as in Jefferson, Rawskia, and Zhang (2008). In addition, because this paper uses the servitisation of manufacturing enterprise as the research object, only observations of manufacturing enterprises are included in the final data set. The final data set includes 76,346 manufacturing enterprises.

4 MANUFACTURING SERVITISATION AND TRADE DURATION IN CHINA

4.1 Manufacturing servitisation in China

(1)

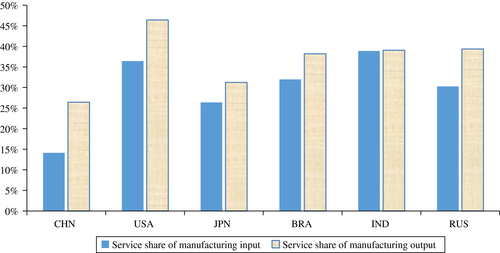

(1)We find that manufacturing servitisation in China is still at a relatively low level. In 2011, servitisation input is less than 15%, and servitisation output is merely 26%, shown in Figure 1. The figures are not only much less than those in developed countries such as the United States and Japan, but also relatively smaller than those in other BRICS countries such as Brazil, India and Russia. Particularly India, a country with a similar level of economic development as China, has levels of both servitisation input and servitisation output which closely approach 40%.

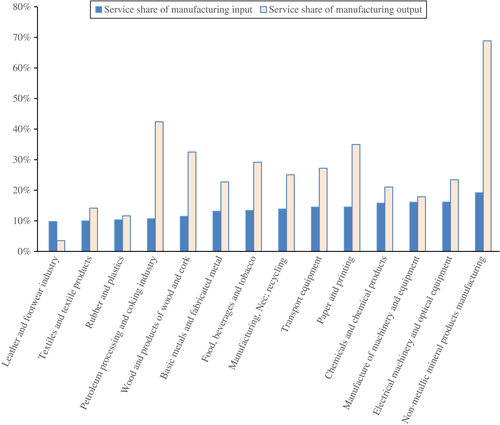

In addition, there are significant differences between industries. In Figure 2, the first three industries with the highest level of servitisation input are “Non-metallic mineral products manufacturing,” “Electrical machinery and optical equipment” and “Manufacture of machinery and equipment,” and the first three industries with the highest level of servitisation output are “Non-metallic mineral products manufacturing,” “Petroleum processing and coking industry” and “Paper and printing.” Five of the above six industries, except “Paper and printing,” are traditional capital and technology-intensive manufacturing industries, and these industries usually have highly servitised in developed countries, which is also consistent with our expectation. Figure 2 also shows that the three industries with the lowest level of servitisation input and servitisation output in China are “Leather and footwear industry,” “Textiles and Textile Products” and “Rubber and Plastics.” These three industries are usually categorised into low-tech industry in China; thus, it is reasonable that they have a lower level of servitisation. However, it is surprising that these three industries have highly servitised in developed countries,5 which is contrary to traditional theory of international labour divisions.

The difference is explained by analysing the characteristics of these three industries. Although the three industries do not need high technology during the process of production and sales, they have a relatively shorter product life cycle and a close relevance with and approach to customers of final products in the industry chain. Thus, it is necessary to input more R&D, design, distribution, marketing and aftermarket of such industries. Enterprises in developed countries, especially multinational enterprises such as Nike and Michelin, have accumulated abundant experiences in the above fields and thus occupied the top stage of the global value chain, while in China, the majority of enterprises in these three industries are international subcontracting firms. The exports of products with Chinese self-owned brands in these three industries have taken up a small proportion.6 Therefore, although the three industries have dominated around half of Chinese total exports, a low level of servitisation still leads to the low end of the global value chain.

4.2 Export duration and servitisation in China

In duration analysis, censored data is one of the important problems which should be paid more attention to. To avoid the estimation bias induced by censored data,7 we only use the observations which had no export record in the year 2000 and indeed exported during the period 2001–06. The full sample concludes 2,917,753 observations, and the yearly export data are transferred into trade spells by getting the triplets “enterprise–product–partner.” After the transformation, there are 1,823,586 trade spells in the full sample. The statistical description of export duration is shown in Table 1. In the export market, 65.48% of the exports can only survive for 1 year, while only 1.10% of the exports can survive for 6 years.

| Survival years | Trade spells | Percentage | Accumulated percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 20,118 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| 5 | 30,781 | 1.69 | 2.79 |

| 4 | 63,341 | 3.47 | 6.26 |

| 3 | 166,101 | 9.11 | 15.37 |

| 2 | 349,228 | 19.15 | 34.52 |

| 1 | 1,194,017 | 65.48 | 100.00 |

| Total | 1,823,586 | 100 |

Note

- The result is similar to that in Chen et al. (2012).

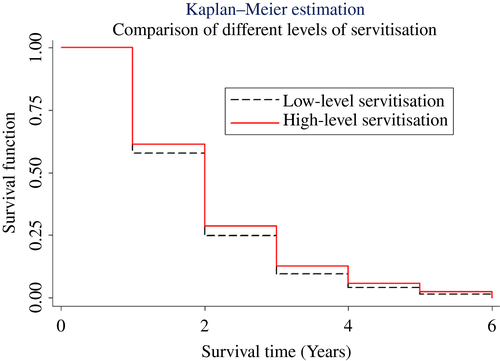

Kaplan–Meier estimation is used to perform non-parameter estimation about the effects of manufacturing servitisation on export duration. The level of servitisation of a trade spell is represented by the service share in the first year of the spell. Let it be noted that the level of manufacturing servitisation is in industry level. Making use of the servitisation of every spell and the median of servitisation in the same year,8 the full sample of export spells is divided into the group with high-level servitisation and the group with low-level servitisation. In Figure 3, survival curves of both groups have the decline trends and survival rates of both groups become stable with the increase in duration. In addition, the survival curve of enterprises with high-level servitisation lies above the other. In other words, enterprises with high-level servitisation have higher survival rate than those with low-level servitisation. The KM curve can directly and briefly give the evidence that the development of manufacturing servitisation increases trade duration of enterprise.

5 REGRESSION AND RESULTS

5.1 Regression strategy

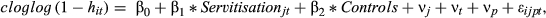

(2)

(2) control for industry, time and province fixed effects.

control for industry, time and province fixed effects.In this paper, the “failure” of trade relationship is defined as an enterprise's exit from the export market, which is caused by zero value of export in some year or the shutdown of the enterprise. The indicator of manufacturing servitisation, Servitisationjt, is presented by servitisation input or servitisation output and implemented regressions, respectively. Servitisation input is measured by the ratio of inputs on service factors to total inputs of manufacturing industry, and servitisation output is measured by the ratio of outputs on service factors to total outputs of manufacturing industry.

Firm-level controls are described as follows. TFP represents the total factor productivity of manufacturing enterprises. According to new-new trade theory, only enterprises with relatively higher productivity can choose to enter the export market. Moreover, only enterprises with higher productivity are able to have better export performance to cope with fierce competition on the international market. We use the LP method provided by Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) to calculate productivity.9

Klratio is the indicator of enterprise capital intensity. The factor endowment theory argues that abundance and efficiency of production factors have crucial effects on an enterprise's export (Mao & Sheng, 2013). Therefore, we use the yearly average balance of net value of fixed assets divided by number of employees of the enterprise to proxy capital intensity.

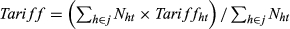

Tariff is the industry tariff rate on final products, which is calculated according to the formula:  . In the formula, j and t denote the industry and year, and h is the product at HS 6-digit level. Nht is the number of products and Tariffht is the ad valorem tariff of product h at year t. We calculate the indicator using the data of import tariff rate from the World Bank and WTO.

. In the formula, j and t denote the industry and year, and h is the product at HS 6-digit level. Nht is the number of products and Tariffht is the ad valorem tariff of product h at year t. We calculate the indicator using the data of import tariff rate from the World Bank and WTO.

Age represents the duration of an enterprise's operation. In other words, age is the total year from the establishment of an enterprise to its shutdown. The logic is that the longer the operation time of an enterprise, the more operation experiences accumulated, which may make it easier for an enterprise to enter and survive in the international market. Roberts and Tybout (1997) provide the empirical evidence that age of an enterprise indeed has important influences on its decision on export participation and export performance. Because only the establishment year of every enterprise is reported, the age of every enterprise is calculated by the following equation: Age = present year − establishment year + 1.

CreditConstraint is the indicator which measures the credit constraint faced by the enterprise. We constitute an aggregative indicator which includes eleven subindicators by following former research of Patrick and Schiavo (2008) and Yang (2012). The subindicators are as follows: (i) proportion of cash flow in total assets of enterprises; (ii) commercial credit ratio, measured by the enterprise accounts receivable divided by total assets; (iii) interest expenses ratio, measured by interest paid by the enterprise divided by fixed assets; (iv) size of enterprise, which is measured by log term of the enterprise total assets; (v) net tangible assets, measured by the percentage of tangible assets in total assets; (vi) debt-paying ability, measured by the proportion of enterprise owners’ equity in total liabilities; (vii) liquidity ratio, measured by the enterprise current assets divided by current liabilities; (viii) solvency ratio, measured by enterprise fixed assets stock divided by total debt; (ix) return on assets, measured by the ratio of total profit after tax to total assets; (x) net profit margin on sales, measured by total profit after tax divided by the enterprise product sales income; and (xi) liquidity constraints, measured by the difference between current assets and current liabilities divided by the total assets. We obtain the 11 subindicators in every year for every enterprise and sum all of them together into an aggregative indicator. The larger the aggregative indicator, the larger the credit constraint faced by the enterprise.

Size measures the relative size of an enterprise which is represented by the ratio of enterprise's gross value of industrial output to gross value of industrial output of the industry in which the enterprise is.

State-owned and Foreign are two dummy variables determining whether an enterprise is a state-owned or a foreign enterprise, respectively. Due to specific political and economic objectives in the process of opening to the world, state-owned enterprises in China have no motivation to innovate and learn from the outside world (Jiang & Zhang, 2008). Therefore, some state-owned enterprises may not be prone to participate in the export market, while foreign enterprises have advantages and higher intention to participate in global trade. A large proportion of foreign enterprises are aiming to make full use of the cheap and high-quality labour forces in China to produce product and then export to a third country.

Country-level variables are used to control for country effects. Consistent with the main trade duration literature, country-level variables mainly include variables from the gravity model. GDP is the log term of GDP of partners. Distance, which proxies the transport costs of the international trade, is the log term of the distance of the most important cities/agglomerations (in terms of population) of the two countries. Comlang represents common language, which could represent the cultural proximity, and is coded based on whether 9% or more of the population use the same language. In addition, we use the indicator CountryRisk from the OECD database for country risk classifications. Landlock is a dummy variable which is set equal to 1 for landlocked countries. Neighbour is a dummy variable which is set equal to 1 if the partner is a country neighbouring China.

5.2 Regression results

Table 2 reports the result of the effects of servitisation on the enterprise's export duration, including servitisation input and servitisation output. The first column of both regressions provides the results without time-dependent characteristics, while the second and third columns of both regressions apply a specific dummy variable of duration spell, Duration2–Duration5, with controlling for different fixed-effect dummy variables.

| Variable | Input | Output | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Servitisation jt | −0.118*** | −0.126*** | −0.049*** | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.014*** |

| (−15.074) | (−16.057) | (−3.652) | (0.428) | (0.555) | (−2.781) | |

| CountryRisk | 0.037*** | 0.038*** | 0.063*** | 0.037*** | 0.038*** | 0.063*** |

| (16.324) | (16.869) | (24.694) | (16.218) | (16.755) | (24.693) | |

| GDP | −0.051*** | −0.054*** | −0.077*** | −0.051*** | −0.054*** | −0.077*** |

| (−81.823) | (−86.858) | (−99.751) | (−81.765) | (−86.789) | (−99.716) | |

| Distance | 0.005*** | 0.006*** | 0.009*** | 0.005*** | 0.005*** | 0.009*** |

| (4.4215) | (4.799) | (7.153) | (4.032) | (4.389) | (7.142) | |

| Landlock | 0.058*** | 0.065*** | 0.062*** | 0.058*** | 0.064*** | 0.0624*** |

| (11.575) | (12.879) | (11.139) | (11.484) | (12.779) | (11.135) | |

| Neighbour | 0.037*** | 0.038*** | 0.037*** | 0.036*** | 0.037*** | 0.036*** |

| (7.068) | (7.138) | (6.231) | (6.881) | (6.940) | (6.199) | |

| Comlang | −0.071*** | −0.075*** | −0.126*** | −0.071*** | −0.075*** | −0.126*** |

| (−21.935) | (−23.057) | (−34.375) | (−21.908) | (−23.025) | (−34.384) | |

| Tariff | −0.051*** | −0.053*** | −0.014** | −0.053*** | −0.055*** | −0.012* |

| (−16.418) | (−16.985) | (−2.257) | (−16.857) | (−17.469) | (−1.894) | |

| TFP | 0.007*** | 0.008*** | 0.0001 | 0.004*** | 0.004*** | 0.0007 |

| (8.409) | (8.894) | (0.044) | (4.351) | (4.540) | (0.417) | |

| Klratio | 0.011*** | 0.012*** | 0.002 | 0.011*** | 0.011*** | 0.002 |

| (14.822) | (15.116) | (1.113) | (13.388) | (13.576) | (1.277) | |

| CreditConstraint | 0.014*** | 0.019*** | 0.018** | 0.012*** | 0.017*** | 0.018** |

| (3.452) | (4.757) | (2.513) | (2.959) | (4.228) | (2.550) | |

| Age | −0.188*** | −0.191*** | −0.229*** | −0.189*** | −0.192*** | −0.229*** |

| (−128.235) | (−129.991) | (−69.728) | (−128.472) | (−130.234) | (−69.755) | |

| Size | −0.037*** | −0.038*** | −0.016*** | −0.034*** | −0.035*** | −0.017*** |

| (−45.909) | (−48.075) | (−8.188) | (−41.533) | (−43.396) | (−8.311) | |

| State-owned | 0.079*** | 0.091*** | −0.003 | 0.079*** | 0.091*** | −0.003 |

| (14.665) | (16.835) | (−0.273) | (14.661) | (16.828) | (−0.284) | |

| Foreign | −0.144*** | −0.152*** | −0.153*** | −0.143*** | −0.151*** | −0.153*** |

| (−72.258) | (−75.930) | (−33.968) | (−71.673) | (−75.300) | (−33.971) | |

| Duration2 | 0.136*** | 0.300*** | 0.136*** | 0.2995*** | ||

| (61.552) | (126.835) | (61.456) | (126.844) | |||

| Duration3 | 0.365*** | 0.611*** | 0.365*** | 0.6112*** | ||

| (97.914) | (154.152) | (97.795) | (154.158) | |||

| Duration4 | 0.378*** | 0.667*** | 0.378*** | 0.6674*** | ||

| (46.520) | (78.896) | (46.477) | (78.908) | |||

| Duration5 | 0.479*** | 0.8041*** | 0.479*** | 0.8042*** | ||

| (24.586) | (40.049) | (24.589) | (40.054) | |||

| Constant | 0.294 | 0.273 | 1.613*** | 1.128*** | 1.074*** | 1.657*** |

| (1.136) | (1.056) | (31.661) | (4.367) | (4.156) | (34.866) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||

| Province FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||

| Firm FE | YES | YES | ||||

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| No. of Obs. | 2,064,076 | 2,063,465 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,063,465 | 2,064,076 |

| Log likelihood | −1,225,086.0 | −1,218,411.2 | −1,160,466 | −1,225,199.9 | −1,218,540.3 | −1,160,469 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, ** significance at 5% and * significance at 10%.

Significant negative coefficients for the variable of manufacturing servitisation input are reported in every regression, which means that servitisation input can significantly reduce the hazard of exiting from the export market of the enterprise. In other words, servitisation input can foster the export duration, which is consistent with our expectation. However, a significant coefficient for servitisation output is only reported when controlling for firm fixed effect and time fixed effect, and the absolute value of coefficient is smaller than that of servitisation input. When controlling for industry, province and time-level fixed effects, insignificant coefficients for the variable of manufacturing servitisation output appear. This means that manufacturing servitisation input in China plays a more important role in export duration than servitisation output.

In addition, the duration dummy variables (Duration2–Duration5) report significant positive estimation coefficients and the coefficients show an increase trend with the elapse of time. The hazard function of export duration has a characteristic of significant positive dependence. In other words, the probability of an enterprise's exit from the export market has an increase with the shift of the duration spell.10

As shown in Table 2, country-level control variables, such as GDP, distance between partners, country risk of partner, and geography characteristics affect trade duration, which is consistent with our expectation and the results shown in Chen et al. (2012). Trade relations from countries with a higher level of GDP, shorter distance to China and lower level of country risk, and along the coast, have the higher survival rate in the export market.

Referring to firm-level control variables, the results are very interesting. The enterprises with a lower level of credit constraint, larger size and older age have the smaller hazard rate of exiting from the export market. The results are consistent with our expectation and the results shown in Esteve-Pérez et al. (2013). State-owned enterprises have a higher hazard rate than non-state-owned enterprises, while foreign enterprises have closer relations with foreign markets, which make trade with foreign markets easier, more frequent and steady. The results are the same with the conclusions argued by Görg et al. (2012).

The industry tariff rate (Tariff) reports the negative coefficient on the hazard rate, which means that the probability of exiting the export market decreases with the increase in the industry import tariff rate on final products. The total factor productivity of manufacturing enterprises (TFP) has negative effects on trade duration of an enterprise, which is not consistent with the results shown in Görg et al. (2012). It demonstrates that in China, enterprises with higher productivity have shorter trade duration, which is also argued by Chen et al. (2012). There is an obvious “productivity paradox” in China.11 An enterprise's capital intensity (Klratio) has a positive effect on the hazard rate. This is explained as follows. China currently has its export comparative advantage in labour-intensive products. Less competitiveness on capital-intensive products leads to a higher risk of exiting the export market of capital-intensive enterprises.

5.3 Robustness

5.3.1 Non-occasional exporter

According to a series of former empirical works on the topic of trade duration, most exporters exist only 1 year. Particularly in China, the 1-year exporters widely exist. To confirm our results, we exclude such so-called one-time or occasional exporters and report the econometric results in Table 3. The variable of manufacturing servitisation input reports a negative and significant coefficient, but the coefficient of manufacturing servitisation output is insignificant. The result demonstrates that the estimation of manufacturing servitisation input is more robust.

| Variable | Non-occasional exporter | Single spell | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Input | Output | |

| Servitisation jt | −0.055*** | −0.006 | −0.096*** | 0.002 |

| (−4.389) | (−1.402) | (−10.874) | (0.705) | |

| CountryRisk | 0.019*** | 0.019*** | 0.035*** | 0.035*** |

| (5.256) | (5.148) | (13.620) | (13.552) | |

| GDP | −0.031*** | −0.031*** | −0.050*** | −0.050*** |

| (−28.225) | (−28.062) | (−71.139) | (−71.067) | |

| Distance | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.005*** | 0.005*** |

| (1.241) | (1.228) | (4.031) | (3.706) | |

| Landlock | 0.035*** | 0.035*** | 0.052*** | 0.052*** |

| (3.987) | (3.990) | (9.494) | (9.410) | |

| Neighbour | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.031*** | 0.030*** |

| (1.025) | (0.940) | (5.212) | (5.066) | |

| Comlang | −0.054*** | −0.054*** | −0.065*** | −0.065*** |

| (−10.421) | (−10.453) | (−17.814) | (−17.802) | |

| Tariff | −0.011* | −0.005 | −0.037*** | −0.038*** |

| (−1.856) | (−0.880) | (−10.606) | (−10.987) | |

| TFP | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.008*** | 0.005*** |

| (0.447) | (−0.650) | (7.943) | (4.904) | |

| Klratio | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010*** | 0.010*** |

| (0.122) | (0.059) | (11.926) | (10.755) | |

| CreditConstraint | 0.014* | 0.013* | 0.009* | 0.007 |

| (1.736) | (1.709) | (1.947) | (1.567) | |

| Age | −0.118*** | −0.118*** | −0.131*** | −0.132*** |

| (−37.737) | (−37.838) | (−80.338) | (−80.534) | |

| Size | −0.012*** | −0.012*** | −0.032*** | −0.030*** |

| (−6.878) | (−6.557) | (−34.957) | (−31.751) | |

| State-owned | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.096*** | 0.096*** |

| (−0.212) | (−0.210) | (15.676) | (15.644) | |

| Foreign | −0.068*** | −0.069*** | −0.118*** | −0.117*** |

| (−16.412) | (−16.406) | (−52.737) | (−52.334) | |

| Duration2 | 1.527*** | 1.527*** | 0.035*** | 0.035*** |

| (456.493) | (456.482) | (13.324) | (13.254) | |

| Duration3 | 1.772*** | 1.772*** | 0.320*** | 0.320*** |

| (380.119) | (380.098) | (71.894) | (71.802) | |

| Duration4 | 1.792*** | 1.792.*** | 0.270*** | 0.270*** |

| (203.669) | (203.691) | (26.936) | (26.903) | |

| Duration5 | 1.904*** | 1.904*** | 0.246*** | 0.246*** |

| (94.921) | (94.926) | (10.874) | (10.877) | |

| Constant | −0.400*** | −0.322*** | 1.012*** | 1.269*** |

| (7.968) | (6.780) | (3.587) | (4.507) | |

| Industry FE | YES | YES | ||

| Province FE | YES | YES | ||

| Firm FE | YES | YES | ||

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| No. of Obs. | 1,230,906 | 1,230,906 | 1,564,717 | 1,564,717 |

| Log likelihood | −671,976 | −671,984 | −886,176.22 | −886,235.52 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, **significance at 5% and *significance at 10%.

At the same time, we use relations with only one trade spell to do separate regressions, and draw the similar conclusions with regressions of the full sample and non-occasional sample. The results are reported in Table 3.

5.3.2 Other measures of export performance

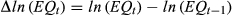

To further confirm the relationship between manufacturing servitisation and firms’ export performance, this paper uses export quantity growth conditional on survival as the measure of export performance to do another robustness check, according to Fernandes and Tang (2014).

Export quantity growth is defined by the following equation:  . EQt represents export quantity of given product in each foreign market by an exporter in year t, which is different from the export volume growth in Fernandes and Tang (2014). The reason is that export quantity will decrease to 0 when a firm exits from export market. The results reported in Table 4 show that the effect of manufacturing servitisation (including manufacturing servitisation input and manufacturing servitisation output) on firms’ export quantity growth is positive, indicating that manufacturing servitisation may not only extend the firm's export duration, but also improve the postentry export quantity growth.

. EQt represents export quantity of given product in each foreign market by an exporter in year t, which is different from the export volume growth in Fernandes and Tang (2014). The reason is that export quantity will decrease to 0 when a firm exits from export market. The results reported in Table 4 show that the effect of manufacturing servitisation (including manufacturing servitisation input and manufacturing servitisation output) on firms’ export quantity growth is positive, indicating that manufacturing servitisation may not only extend the firm's export duration, but also improve the postentry export quantity growth.

| Variable | Input | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Servitisation jt | 0.209*** | 0.049*** |

| (6.729) | (3.426) | |

| CountryRisk | 0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.020) | (−0.000) | |

| GDP | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.873) | (0.869) | |

| Distance | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.298) | (0.304) | |

| Landlock | −0.011 | −0.010 |

| (−0.995) | (−0.981) | |

| Neighbour | −0.012 | −0.012 |

| (−1.162) | (−1.168) | |

| Comlang | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| (−0.443) | (−0.472) | |

| Tariff | 0.038** | 0.036** |

| (2.434) | (2.332) | |

| TFP | −0.005 | −0.008*** |

| (−1.552) | (−2.587) | |

| Klratio | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| (0.931) | (0.799) | |

| CreditConstraint | −0.028** | −0.029** |

| (−2.014) | (−2.103) | |

| Age | −0.044*** | −0.045*** |

| (−5.089) | (−5.140) | |

| Size | 0.077*** | 0.079*** |

| (14.950) | (15.389) | |

| State-owned | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| (−0.268) | (−0.214) | |

| Foreign | 0.007 | 0.006 |

| (0.645) | (0.583) | |

| Constant | 1.067*** | 0.843*** |

| (9.517) | (7.986) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES |

| Time FE | YES | YES |

| No. of obs. | 784,586 | 784,586 |

| R 2 | .0366 | .0366 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, **significance at 5% and * significance at 10%.

5.3.3 Different channels of export performance

In addition, two estimations about channels through which manufacturing servitisation affects firm-level export performance are also provided.

First, according to Crozet and Milet (2015), manufacturing servitisation seems to be a main strategy which leads firms to differentiate their products further in order to charge higher margins and improve their competitiveness. Therefore, product differentiation is one of the important channels through which manufacturing servitisation affects firm export duration. Based on Rauch (1999) and Besedeš and Prusa (2006b), we classify export products into three categories: homogeneous products, the products traded on an organised exchange; reference priced products, the products not sold on exchanges but whose benchmark prices exist; and differentiated products.

A binary variable is created as the dependent variable, which equals 1 if the product is considered as a differentiated product and 0 if it is not. According to Bernard and Jensen (2004), Albornoz, Calvo-Pardo, Corcos, and Ornealas (2012) and Fernandes and Tang (2014), we use a linear probability model to construct the regression and report the results in Table 5.

| Variable | Product differentiation | R&D intensity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Input | Output | |

| Servitisation jt | 0.012*** | −0.001 | 1.838* | −1.596*** |

| (2.634) | (−0.070) | (1.817) | (−3.065) | |

| Tariff | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.347 | 0.588 |

| (0.847) | (1.032) | (0.633) | (1.062) | |

| TFP | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.096 | −0.098 |

| (1.518) | (1.261) | (−0.790) | (−0.811) | |

| Klratio | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.158 | −0.156 |

| (0.712) | (0.690) | (−1.185) | (−1.169) | |

| CreditConstraint | −0.004* | −0.004* | 0.260 | 0.265 |

| (−1.772) | (−1.794) | (0.554) | (0.564) | |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.428 | −0.449 |

| (−0.678) | (−0.723) | (−1.372) | (−1.439) | |

| Size | −0.003*** | −0.002*** | 0.009 | −0.001 |

| (−3.427) | (−3.328) | (0.048) | (−0.008) | |

| State-owned | −0.010*** | −0.010*** | −2.195*** | −2.234*** |

| (−3.435) | (−3.433) | (−3.129) | (−3.186) | |

| Foreign | 0.003** | 0.003** | −0.033 | −0.035 |

| (2.104) | (2.064) | (−0.088) | (−0.096) | |

| Constant | 0.683*** | 0.663*** | 6.841* | 0.619 |

| (42.793) | (44.579) | (1.804) | (0.166) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| No. of obs. | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 88,652 | 88,652 |

| R 2 | .5697 | .5697 | .7905 | .7905 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, **significance at 5% and *significance at 10%.

The coefficient of manufacturing servitisation input is positive and statistically significant, which supports the hypothesis of the paper: manufacturing servitisation input focuses more on the product innovation and product differentiation from competitors, and thus, exporters can gain competitive advantage and enter a foreign market. However, a statistically insignificant coefficient is reported for manufacturing servitisation output. The reason is as follows: there is a dual relationship between manufacturing servitisation output and product differentiation. On the one hand, manufacturing servitisation output facilitates the business strategy of product differentiation by means of product-service systems and integrated product-service solutions. On the other hand, manufacturing servitisation output leads firms to specialise in the segment of service provision, ignoring product innovation (Crozet & Milet, 2015).

Second, we check the other channel, R&D, which can extend the export duration of firms through the improvement of the enterprise's innovation ability and competitiveness. R&D intensity is computed as the ratio of R&D expenditures to total sales. The results in Table 5 show that manufacturing servitisation input does significantly improve the R&D intensity of enterprises, while manufacturing servitisation output does not. The reason is that R&D mainly involves the upstream link of manufacturing industry, while manufacturing servitisation output (e.g., after-sales service) is mainly related to the downstream link of manufacturing industry.

5.3.4 Different trade patterns and different ownerships

To further explore the natural characteristics of Chinese exports, we run different regressions considering different trade patterns and different ownerships.

According to Dai, Maitra, and Miaojie (2016), exporting firms are divided into two types on the basis of whether the firms mainly engage in processing exports (PE) or ordinary exports (OE). The dummy variable PE which proxies a processing exporter is calculated by following the rules that the share of processing export exceeds zero or 50% or is equal to 1, respectively. When the proportion is equal to 1, the firm is considered as a pure processing exporting firm.

Table 6 reports the results. The coefficients of the interaction terms between manufacturing servitisation and the dummy of processing exporters are always positive and statistically significant. The results indicate that manufacturing servitisation can further reduce the hazard of exit for ordinary exporting (OE) firms compared to processing exporting (PE) firms. The reason is that OE firms are almost involved in all stages of product development, manufacture, distribution and after-sales, while PE firms only produce for brand-name foreign buyers, which are only responsible for the last stages of production in a global supply chain (Fernandes & Tang, 2014).

| Variable | Share of processing export>0 | Share of processing export>50% | Share of processing export=1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Input | Output | Input | Output | |

| Servitisation jt | −0.123*** | − | −0.161*** | −0.054*** | −0.067*** | −0.020*** |

| (−8.228) | 0.045*** (−7.400) | (−9.799) | (−8.000) | (−4.934) | (−3.873) | |

| Servitisationjt*PE | 0.180*** | 0.066*** | 0.181*** | 0.0624*** | 0.222*** | 0.053*** |

| (11.299) | (8.762) | (11.400) | (8.431) | (7.647) | (4.588) | |

| PE | 0.309*** | 0.073*** | 0.311*** | 0.065*** | 0.366*** | 0.031 |

| (10.048) | (5.559) | (10.169) | (5.213) | (6.509) | (1.459) | |

| CountryRisk | 0.062** | 0.062*** | 0.063*** | 0.063*** | 0.062*** | 0.062*** |

| (24.492) | (24.504) | (24.617) | (24.602) | (24.449) | (24.488) | |

| GDP | −0.077*** | −0.077*** | −0.076*** | −0.076*** | −0.077*** | −0.077*** |

| (−99.545) | (−99.502) | (−99.283) | (−99.274) | (−99.747) | (−99.705) | |

| Distance | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** |

| (7.110) | (7.093) | (7.066) | (7.075) | (7.112) | (7.106) | |

| Landlock | 0.0627*** | 0.063*** | 0.063*** | 0.063*** | 0.0625*** | 0.063*** |

| (11.186) | (11.153) | (11.242) | (11.184) | (11.162) | (11.150) | |

| Neighbour | 0.036*** | 0.036*** | 0.0361*** | 0.0357*** | 0.0365*** | 0.036*** |

| (6.193) | (6.129) | (6.150) | (6.087) | (6.2240) | (6.181) | |

| Comlang | −0.126*** | −0.126*** | −0.125*** | −0.126*** | −0.126*** | −0.126*** |

| (−34.185) | (−34.211) | (−34.167) | (−34.214) | (−34.235) | (−34.268) | |

| Tariff | −0.013** | −0.009 | −0.013** | −0.008 | −0.014** | −0.011* |

| (−2.046) | (−1.449) | (−2.075) | (−1.322) | (−2.234) | (−1.748) | |

| TFP | −0.000 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | −0.000 | 0.001 |

| (−0.021) | (0.590) | (0.055) | (0.662) | (−0.089) | (0.3960) | |

| Klratio | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.0011 | 0.0018 | 0.0008 | 0.0014 |

| (0.585) | (1.024) | (0.653) | (1.093) | (0.488) | (0.813) | |

| CreditConstraint | 0.018** | 0.020*** | 0.0185** | 0.0196*** | 0.0182** | 0.0189*** |

| (2.4346) | (2.6986) | (2.560) | (2.716) | (2.516) | (2.617) | |

| Age | −0.227*** | −0.228*** | −0.227*** | −0.228*** | −0.228*** | −0.228*** |

| (−69.220) | (−69.272) | (−69.163) | (−69.324) | (−69.481) | (−69.504) | |

| Size | −0.016*** | −0.016*** | −0.015*** | −0.016*** | −0.017*** | −0.017*** |

| (−7.940) | (−8.073) | (−7.677) | (−7.782) | (−8.431) | (−8.558) | |

| State−owned | −0.003 | −0.005 | −0.002 | −0.004 | −0.0033 | −0.004 |

| (−0.291) | (−0.430) | (−0.203) | (−0.351) | (−0.3065) | (−0.356) | |

| Foreign | −0.147*** | −0.147*** | −0.146*** | −0.146*** | −0.150*** | −0.150*** |

| (−32.352) | (−32.236) | (−31.964) | (−31.988) | (−33.204) | (−33.243) | |

| Duration2 | 0.299*** | 0.299*** | 0.299*** | 0.299*** | 0.300*** | 0.300*** |

| (126.716) | (126.789) | (126.668) | (126.747) | (126.829) | (126.845) | |

| Duration3 | 0.611*** | 0.611*** | 0.610*** | 0.611*** | 0.611*** | 0.611*** |

| (154.005) | (154.083) | (153.954) | (154.044) | (154.140) | (154.163) | |

| Duration4 | 0.666*** | 0.667*** | 0.666*** | 0.667*** | 0.667*** | 0.667*** |

| (78.791) | (78.864) | (78.766) | (78.838) | (78.863) | (78.890) | |

| Duration5 | 0.802*** | 0.804*** | 0.802*** | 0.803*** | 0.803*** | 0.804*** |

| (39.966) | (40.031) | (39.957) | (40.006) | (40.022) | (40.037) | |

| Constant | 1.489*** | 1.613*** | −0.464*** | 1.602*** | 1.588*** | 1.650*** |

| (28.423) | (33.664) | (−8.460) | (33.201) | (31.094) | (34.682) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| No. of obs. | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 |

| Log likelihood | −1,160,366 | −1,160,393 | −1,160,362 | −1,160,394 | −1,160,394 | −1,160,415 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, **significance at 5% and *significance at 10%.

Moreover, we divide the full sample into two different groups: domestic exporters and foreign-owned exporters. The dummy variable Foreign, which proxies a foreign-owned exporter, is calculated by following the rules that the share of foreign paid-up capital exceeds zero or 25%, respectively (Lu, 2008; Nie, Jiang, & Yang, 2012). Table 7 reports the results. All coefficients of the interaction terms are positive and statistically significant, indicating that the negative impact of manufacturing servitisation on the exit hazard of domestic exporters is significantly stronger than that of foreign exporters. A possible explanation for such results is that the upstream and downstream service links (R&D and sales services) of foreign exporters mainly depend on the home country, not the host country. On the contrary, the domestic exporters benefit more from manufacturing servitisation.

| Variable | Share of foreign paid−up capital >0 | Share of foreign paid−up capital >25% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Output | Input | Output | |

| Servitisation jt | −0.136*** | −0.031*** | −0.151*** | −0.044*** |

| (−8.115) | (−4.325) | (−8.514) | (−5.638) | |

| Servitisationjt*Foreign | 0.144*** | 0.026*** | 0.157*** | 0.042*** |

| (8.684) | (3.3414) | (8.949) | (4.8720) | |

| Foreign | 0.123*** | −0.110*** | 0.116*** | −0.117*** |

| (3.841) | (−8.1231) | (3.415) | (−7.8679) | |

| CountryRisk | 0.063*** | 0.063*** | 0.063*** | 0.063*** |

| (24.686) | (24.688) | (24.652) | (24.6516) | |

| GDP | −0.077*** | −0.0766*** | −0.076*** | −0.076*** |

| (−99.701) | (−99.710) | (−99.394) | (−99.404) | |

| Distance | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** | 0.009*** |

| (7.138) | (7.132) | (7.0869) | (7.078) | |

| Landlock | 0.062*** | 0.062*** | 0.0626*** | 0.0626*** |

| (11.145) | (11.134) | (11.1796) | (11.170) | |

| Neighbour | 0.037*** | 0.036*** | 0.036*** | 0.036*** |

| (6.271) | (6.204) | (6.119) | (6.053) | |

| Comlang | −0.126*** | −0.126*** | −0.126*** | −0.126*** |

| (−34.370) | (−34.384) | (−34.281) | (−34.298) | |

| Tariff | −0.015** | −0.012* | −0.010* | −0.007 |

| (−2.367) | (−1.844) | (−1.647) | (−1.062) | |

| TFP | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.000 | 0.001 |

| (0.026) | (0.468) | (−0.063) | (0.421) | |

| Klratio | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| (0.655) | (1.1610) | (0.999) | (1.482) | |

| CreditConstraint | 0.0162** | 0.0183** | 0.0116 | 0.0139* |

| (2.243) | (2.536) | (1.6053) | (1.928) | |

| Age | −0.227*** | −0.229*** | −0.229*** | −0.230*** |

| (−69.389) | (−70.075) | (−69.858) | (−70.561) | |

| Size | −0.0163*** | −0.0166*** | −0.015*** | −0.016*** |

| (−8.319) | (−8.3489) | (−7.8363) | (−7.899) | |

| Duration2 | 0.2993*** | 0.300*** | 0.299*** | 0.299*** |

| (126.7556) | (126.831) | (126.688) | (126.759) | |

| Duration3 | 0.611*** | 0.611*** | 0.610*** | 0.611*** |

| (154.043) | (154.141) | (153.939) | (154.034) | |

| Duration4 | 0.6665*** | 0.6673*** | 0.666*** | 0.667*** |

| (78.793) | (78.896) | (78.747) | (78.849) | |

| Duration5 | 0.803*** | 0.804*** | 0.8025*** | 0.8042*** |

| (39.970) | (40.052) | (39.9574) | (40.0427) | |

| Constant | 1.452*** | 1.630*** | 1.449*** | 1.633*** |

| (26.794) | (33.790) | (26.250) | (33.694) | |

| Firm FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| No. of obs. | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 | 2,064,076 |

| Log likelihood | −1,160,428 | −1,160,463 | −1,160,286 | −1,160,316 |

Note

- ***Significance at 1%, **significance at 5% and *significance at 10%.

6 CONCLUSION

As a growing characteristic of global firms, manufacturing servitisation has become a trend all over the world and attracted more and more attention. Manufacturing firms are more prone to increase their values and profits through the development of service factors. However, the research about effects of manufacturing servitisation on export performance is scarce. This paper makes use of high-quality and detailed customs data and firm-level data from China to analyse the relationship between trade duration and manufacturing servitisation.

This paper finds a significant positive effect of manufacturing servitisation input on export duration of Chinese manufacturing enterprises. The positive effect of manufacturing servitisation output on export duration in Chinese enterprise can also be observed. However, the effects are not robust. The results demonstrate the contribution of manufacturing servitisation input to export performance. Empirical results also confirm that the impact of manufacturing servitisation on export duration of exporters is being driven by product differentiation and R&D. The ordinary exporters and domestic exporters benefit more from manufacturing servitisation. The service factors have become the important production factors in Chinese manufacturing enterprise. However, China is still at the primary stage of manufacturing servitisation. It means that Chinese manufacturing enterprises are still not like enterprises in other developed countries, which have sufficient ability to participate in international competition, not only by focusing on the production of physical products, but also the whole life cycle of production. Chinese manufacturing enterprise should pay more attention to the whole value chain and seek the transformation from a pure manufacturing enterprise to a service manufacturing enterprise.