European Union Market Access Conditions and Africa's Extensive Margin of Food Trade

Inmaculada Martínez-Zarzoso gratefully acknowledges the financial support received from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Project reference: ECO2014-58991-C3-2-R).

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of two European Union (EU) market access regulations in the food sector presumed to simultaneously affect firms’ decisions to export food products to the EU. We analysed EU pesticide standards on African exports alongside a complementary non-tariff measure in the form of a minimum entry price regulation, which aims to protect EU growers of certain fruits and vegetables against international competition. Analysis was based on Africa's exports of tomatoes, oranges, and lime and lemon to the EU between 2008 and 2013, using the gravity model of trade. Our results show that EU market access conditions constitute significant barrier to the formation of new trade relation between the EU and Africa. In addition, initiation of trade relationships is contingent not only on market access conditions but also on domestic market constraints in Africa. These results imply that negotiating preferential entry prices duties and the removal of domestic market restraints as well as strengthening domestic capacity to comply with EU standards to enhance continuous market access for the continent could stimulate food trade along the extensive margin.

1 Introduction

The last decades have witnessed a structural shift from the exports of traditional agricultural food products such as cocoa and sugar by most developing countries to non-traditional high-value agricultural food products such as processed foods and fresh fruits and vegetables (Reardon et al., 2009). Thus, trade is increasingly playing a significant role in the provision of food, export earnings and economic growth for many developing countries. However, this cannot be categorically said for African countries, many of which have gradually become predominant net food importers (World Bank, 2012). In addition, the continent continues to depend majorly on exports of traditionally valued agricultural food products despite the structural shift of most developing countries to non-traditional high-value agricultural food products. Consequently, this may jeopardise the significant role played by food exports in stimulating economic growth and as a means of poverty reduction especially for sub-Saharan African countries, many of which depend heavily on agriculture for sustenance. This weak integration of most African countries into the global economy can be an impediment to the developmental progress of the continent, mainly because deep trade integration is widely viewed as the most promising avenue to achieving economic growth (Nicita and Rollo, 2015).

Numerous factors have been linked to the weak integration of African countries in global markets, and these include high cost of exporting and poorly developed trade facilitation infrastructure (Iwanow and Kirkpatrick, 2009; Djankov et al., 2010; Portugal-Perez and Wilson, 2012), domestic supply constraints (Xiong and Beghin, 2011) and trade inhibiting non-tariff barriers (NTBs) imposed on its exports (Otsuki et al., 2001; Shephard and Wilson, 2013). Of these obstacles, NTBs have been identified as the single most important market access condition for Africa's exports (Czubala et al., 2009), thus necessitating a careful study of these barriers. Consequently, a better understanding of the actual implications of such NTBs for market access is of paramount importance for the population of this continent, the majority of whom depend on agricultural activities for their livelihood.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of two important non-tariff regulations imposed by the European Union (EU) on Africa's food exports. The first is food safety standard, which has gained importance in recent years due to a number of food scares in developed countries (UnNevehr, 2003). This makes standards to constitute one of the most important market access conditions imposed by the EU on food exports. Standards are of particular concern to exporters due to their dual ability to be used as protectionist measure in preventing imports and their legitimate use for the protection of consumers’ health and safety. On the one hand, there is the ‘standards as barrier’ perspective where standards have been viewed as a barrier to export penetration due to their trade costs effects. The proposition is that standards affect trade competitiveness because meeting stringent standards imposes excessive costs of compliance borne by the producers which might erode export competitiveness and affect the profitability of the export product, thereby acting as a barrier to trade (Maskus et al. 2001). In addition, the increasing stringency of these standards implies a rising cost of compliance. Higher compliance costs for developing countries discourage potential exporters from penetrating foreign markets, drives less productive firms away from international markets, and decreases both the trade volume and sustainability of the remaining exporters (Bao and Chen, 2013). The situation is aggravated for exporters from Africa due to their lack of necessary infrastructure and technology, which inhibits their ability to comply with importing countries’ standards. However, standards can also be trade enhancing once the right environment is set up (Jaffee and Henson, 2004). On the one hand, the view of standards as a catalyst to trade argument is in line with the demand-enhancing effects of standards. According to this stance, standards help in building value into certified goods and services as they provide consumers with information and assurances about their health and safety, therefore stimulating import demand (Moenius, 2004). Standards also remedy asymmetric information, providing information to producers about the specifications and technicalities of the products, which can lead to technology diffusion and innovation (Baller, 2007).

A second but usually neglected market access condition that exporters face, when exporting fresh fruits and vegetable to the EU, is the EU entry price control. This measure aims to protect EU growers of 15 fruit and vegetable products from international competition by the imposition of a minimum entry price requirement. This non-tariff measure acts to restrict the synthetic import prices below the predetermined entry price, leading to the imposition of a specific duty on exports, when the import price falls below a predetermined minimum entry price. This erodes the export competitiveness while increasing EU growers’ competitiveness relative to exporters’. This system of protection is known as the EU entry price system (hereafter EPS), and is imposed simultaneously with the EU safety standards.

This study therefore investigates the implications of EU entry price conditions and safety standards on Africa's exports, on the probability of initiating new export relationship with the EU (the extensive margin1 of trade). We investigated the impact within a gravity model using panel datasets focusing on fresh fruit and vegetable exports, – namely tomatoes, oranges, and limes and lemons – between 2008 and 2013. The choice of the export products is due to the fact that they are simultaneously subjected to EU entry price control and also attract stringent pesticide regulations due to their perishable nature and susceptibility to food safety risks. In our analysis, we investigated the potential impacts of food safety standards on Africa's exports, using EU food safety regulations on allowable pesticide residues in food. Although EU food safety standard regulations encompass many requirements, all of which need to be satisfied, however, the focus of this study is on pesticide standards. Of all EU food safety requirements, the violation of the acceptable maximum residual limits (MRLs) of pesticides in food or feed products represents the second largest reason for border rejections of third country's exports to the EU; this consequently constitutes a loss of export revenue and products for the exporters. In fact, the violations of pesticide residue limits constitute about 70 per cent of EU rejections of all Africa's fruit and vegetable exports between 2008 and 2013, thus indicating an important market access problem (EC RASFF, 2014).

Furthermore, these products provide a good case study to analyse the implications of these two EU regulations on EU–African trade. This is because the EU is the largest importer of fresh fruits and vegetables in the world, importing a significant amount of tropical fruits and vegetables from African countries whose favourable climatic conditions give then a comparative advantage. Moreover, EU trade policies would have significant impacts on the African countries as the existence of preferential arrangements between the two regions has made the EU a major destination for African exports. For instance, according to Kareem et al. (2015), aside intra-Africa trade which make up between 67.1 and 91.6 per cent of African total export of these products, the EU represents the most important trading partner of African countries for these products. In the case of tomatoes, the EU absorbed about 9.4 per cent of the continent's tomato exports between 1995 and 2007, with the share falling drastically to about 2.9 per cent between 2008 and 2013. However, African exports of oranges, and limes and lemons to the EU accelerated from about 13 per cent and 18.9 per cent respectively, between 1995 and 2007 to about 18.9 per cent and 27.4 per cent respectively, between 2008 and 2013. To what extent the export performances of these three products can be attributed to the influence of EU standards and entry price control remains to be determined.

This study is motivated by the recent literature on firm heterogeneity which reveals that the growth of developing countries' trade was predominantly due to the expansion of trade along the extensive margin rather than due to the growth in the volume of trade (Reis and Farole, 2012; Nicita and Rollo, 2015). In spite of this assertion, we argue that the ability of African countries to initiate or penetrate new markets might ultimately be constrained by stringent importing countries market conditions. Thus, the analysis of the impact of the aforementioned EU market conditions in the food sector on Africa's exports along the extensive margin is crucial to understanding the process of entry and exist in export markets and also identify which factor may be the biggest constraint to Africa's export competiveness. For instance, studies that look at the impact of EU market conditions in the food sector on Africa's exports have predominantly focused on the intensive margin (Otsuki et al., 2001; Gebrehiwet et al., 2007). However, the implications of EU food regulations on market access at the extensive margin of trade have received less attention. Having a better understanding of the effects of these two EU market access conditions in the food sector and their effect on potential exporters is therefore important from a policy perspective.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides background information on the two EU market access conditions. Section 3 discusses the methodology and the data. Section 4 discusses the results, Section 5 the robustness check and the final section concludes.

2 Market Access Requirements in EU Food Sector

This section provides background information on the two important and complementary non-tariff measures on fruits and vegetables in the EU – pesticides standards and the EU EPS. In this study, we focus on three selected products at a HS6 disaggregated level, namely tomatoes, oranges, and limes and lemons. The choice of these fruit and vegetable products is due to the fact that they have the potential to retain high levels of different pesticides. In addition, they represent important products subjected to the EU entry price control.

2.1 Pesticide Standards Regulations in the EU

Pesticides are active substances used to protect crops from pests and diseases before and after harvest. While their major aim is to increase the quantity and quality of the produce, however, misuse can pose significant risks to human health and the environment. This necessitates countries to place stringent safety standards on pesticide use and residue levels. Thus, stringent risk assessments are usually undertaken to determine the maximum acceptable daily intake of pesticide over a person's lifetime that would pose no adverse consequences.

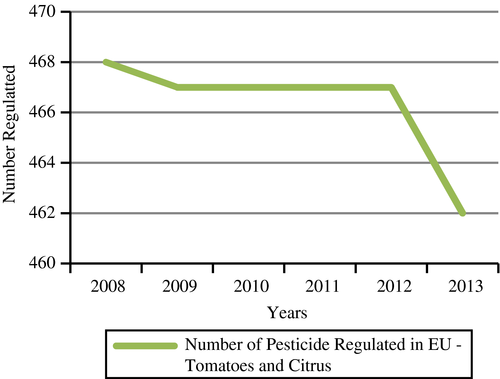

In the EU, pesticide regulations are governed by European Commission (EC) Directive 396/2005,2 which establishes the MRLs of pesticides allowed in products of plants and animal origin intended for consumption, based on scientific evidence from risk assessments. This directive which became operational in September 2008 harmonised all pesticides standards among EU Member countries. With this directive, EU pesticide regulations became more encompassing as more than thrice the previous number of pesticides were regulated. Figure 1 displays the number of pesticides regulated for each of the three products considered in this study. The EU regulates a large number of pesticide standards on tomatoes, oranges, and limes and lemons, amounting to 468 standards in 2008, which declined to about 462 in 2013. This recent reduction in the number regulated is due to some previously regulated pesticide standards being exempted from regulation, because subsequent scientific risk assessment has shown them to be safe for consumption.

Source: Authors' computation.

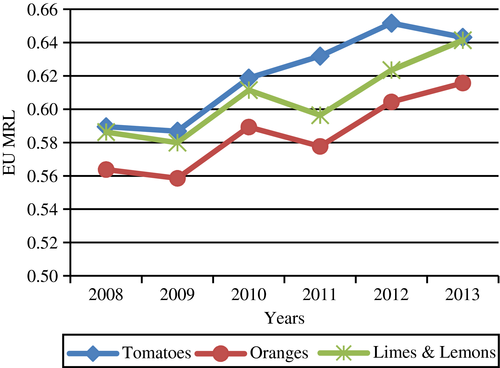

While numbers tell us the extent of the standards, they do not however provide information about the intensity or stringency of the standards. This is provided by the maximum residue limit imposed on the pesticides. MRL is the unit of measure of pesticide standards and its stringency level. Thus, such pesticide standards are regulated using the maximum residue levels of the pesticide substance found in or on food, based on good agricultural practices. The stringency level of pesticide standards is measured in parts per million (given in mg/kg). Figure 2 displays the average stringency level of the subsets of harmonised pesticides regulated by the EU between 2008 and 2013.

Source: Authors' computation.

The stringency of the pesticide standards in the EU differs significantly among the three products considered (Figure 2). From a high stringency level in 2008, pesticide standards on these three products became more restrictive in 2009 (a decrease in the maximum allowed is observed in Figure 2, which signifies higher stringency and thus, a more restrictive standard). Furthermore, the stringency levels of oranges, and limes and lemons were more restrictive in 2011 compared to 2010, while levels for tomatoes were more restrictive in 2013 compared to what was obtained in 2012. Thus, the net effect of this restrictiveness is an empirical one.

2.2 EU Entry Price System for Fruits and Vegetables

The second aspect of food regulation market germane to countries importing certain fresh fruits to the EU is a non-tariff measure in the form of ‘behind the border’ price requirement known as the EU entry price control. This system of regulation protects EU growers of 15 fruit and vegetable products including tomatoes, oranges and lemons, from international competition by regulating the entry prices of these products for exporting countries. This is done by penalising third countries exports whose prices fall below a predetermined seasonally varying stipulated minimum entry price, through the imposition of specific duties on these exports (Goetz and Grethe, 2010). The EPS is a non-tariff measure, which aims to restrict import prices below the stipulated entry price and act to erode the competitiveness of exporters and increase the competitiveness of EU growers relative to exporters’. For instance, if the exporter supplies the product at a price below the maximum stipulated entry price as a result of having a competitive edge due to lower costs of production, then a predetermined specific duty is levied as a penalty factor. The EU EPS came into force on 1 July 1995 replacing the old reference price system.

To calculate the entry price duties, information is needed on the import price of the product and the predetermined entry price. However, in the EU a large proportion of EU fruit and vegetable imports are paid on commission, implying that the import price of the product is not determined until it is sold in the EU markets (Goetz and Grethe, 2010). The EC therefore calculates a ‘synthetic’ import price, which the Commission refers to as the standard import values (SIVs). The applicable SIVs, published on a daily basis by the EC, are calculated from a survey of fruit and vegetable prices for each product and export origin, collated from the designated representative fruit and vegetable wholesale markets in all the EU member countries (Goetz and Grethe, 2009). For each country and product, a SIV3 is then calculated on a daily basis as a weighted average of all the wholesale market prices collated from all these representative markets, less the marketing costs, transportation costs and custom duties (EC Regulation 3223/94).

The EU schedule of entry price (EP) varies by season with lower EPs imposed during the EU's off-season period of the applicable fruits and vegetables, and high EPs are imposed when the fruits and vegetables are in season in the EU (Cioffi and dell’ Aquila, 2004). Although almost all African countries enjoy preferential access to the EU market under the ‘Every Thing but Arms Agreement’, in terms of zero tariff on their exports; however, this benefit does not extend largely to EP as only Morocco enjoys preferential EP duties while the others have to comply with the EU's most favoured nation (MFN) market access conditions in the EPS. In other words, Morocco is not exempted altogether from paying the EP duties to the EU but rather pays lower EP duties relative to other countries while the other countries pay the full predesignated EP duties.

Table 1 shows the schedule of minimum EPs for the three products considered in this study. For tomatoes and lemons, their EPs run throughout the whole year from the first of January of the year to the thirty-first of December, as EU growers are not that competitive in producing these products. However, the EPS runs between December and May for oranges, which correspond to the post-harvest period for EU growers – a period in which oranges are out of season and EU domestic prices are less competitive. This is in sharp contrast to African countries, most of which have relative price competitiveness all year round due to the favourable tropical climate and cheaper labour. In the case of tomatoes, the EP varies between 52.60 €/100 kg and 112.60 €/100 kg); for oranges, the maximum EP is 35.40 €/100 kg and the minimum is 32.60 €/100 kg; but varies between 46.20 €/100 kg and 55.80 €/100 kg in the case of lemon. Exporters whose export price falls below the maximum EP are penalised for bringing in products relatively cheaper than domestic ones through the imposition of EP duties. For tomatoes, the duty ranges from a minimum of 0 €/100 kg to a maximum of 29.8 €/100 kg; the range for oranges is between 0 €/100 kg and 7.10 €/100 kg, and between 0 €/100 kg and 25.6 €/100 kg for lemons.

| Tomatoes | Oranges | Lemonsa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application date | 1 January–31 December | 1 December–31 May | 1 January–31 December |

| Minimum EP (€/100 kg) | 52.60 | 32.60 | 46.20 |

| Maximum EP (€/100 kg) | 112.60 | 35.4 | 55.8 |

| Specific EP duties (€/100 kg) | 0–29.80 | 0–7.10 | 0–25.60 |

| Higher EP duty (€/100 kg) | 29.80 | 7.10 | 25.60 |

Note

- a EU EPS only covers lemon but does not extend to lime.

- Source: EC, TARIC Database (2014).

The applicable EP duties are determined as follows: if the synthetic import price (in this case SIV) is equal or greater than the maximum EP in any given season, no EP duty is levied. In other words, export products whose price is equal to or greater than the maximum entry price always attract zero EP duties. However, if the ‘synthetic import price’ is below the maximum EP, but above the minimum EP, an ad valorem tariff plus a specific EP duty is levied on the product. If the synthetic import price is equal to or below the minimum EP in any given season, an ad valorem tariff applies plus the highest EP duty which in our case is 29.80 €/100 kg for tomatoes, 7.10 €/100 and 25.60 €/100 kg for oranges and lemon, respectively. Thus, the EPS penalises exporters that bring into the EU competitive exports by making cheaper exports to become more expensive.

To get a clear idea of the EPS, we take an example from the EC TARRIC website. Table 2 depicts the schedule of MFN EP levied on an African country that has a preferential agreement with the EU. On 1st of April 2013, the synthetic import prices of tomatoes from Morocco, Tunisia and all other African countries were 75.70 €/100 kg, 97.00 €/100 kg and 98.90 €/100 kg, respectively (EC TARRIC, 2014). Using Table 2, this implies that all these African countries bring very competitive exports to the EU, and these prices are well below the EU minimum EP of 103.60 €/100 kg (case 5). Thus, protecting EU growers from this price competition led to the imposition of a penalty factor on their exports in the form of an additional maximum EP duty of 29.80 €/100 kg, amounting to a total import price of 105.50 €/100 kg for Morocco, 126.80 €/100 kg for Tunisia and 128.7 €/100 kg for all other African countries. The addition of this additional duty eroded the competitiveness of these exporters by making their cheap exports to become very expensive. Hypothetically, if an African country say Ghana was to arrive at the EU border at a CIF price of 112.6 €/100 kg (case 1), no specific duty is levied on the product because the EU EPS requirement is perfectly satisfied. In this case, the CIF price is equivalent to the prevailing maximum EP of 112.6 €/100 kg. Thus, to avoid these EP duties, this might alter the exporters’ pricing behaviour by making them supply their product to the EU at the maximum possible price, so as to avoid the additional EP duties (Goetz and Grethe, 2009).

| Cases | EP Conditions for Different Import Prices (MP) in Comparison with EPs | EP Duties |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | MP ≥ 112.60 €/100 kg | – |

| 2 | MP ≥ 110.30 €/100 kg | 2.30 €/100 kg |

| 3 | MP ≥ 108.10 €/100 kg | 4.50 €/100 kg |

| 4 | MP ≥ 105.80 €/100 kg | 6.80 €/100 kg |

| 5 | MP ≥ 103.60 €/100 kg | 9.00 €/100 kg |

| 6 | MP ≥ 0 €/100 kg | 29.80 €/100 kg |

- Source: EC TARIC (2014).

2.3 Measuring EU Food Regulations

This subsection provides information on how the two measures of EU food regulations on EP and food safety standards were constructed.

2.3.1 Stringency of Standards

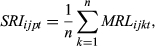

(1)

(1)Our standard restrictiveness index is in levels and not in changes. While we acknowledge that yearly changes in pesticide standards would have been the ideal variable, we are constrained to estimate the variable in levels given the nature of pesticide dataset. First, EU standards are unchanged in some years, especially in the early period. Due to the lack of time variation in MRLs in the early years, estimating in differences would have resulted into zero MRLs. Such zero MRLs would have distorted our results as zero MRL implies a much more stringent and very difficult to meet standard. Moreover, it is even rare for there to be zero limit on pesticides that have not been prohibited as pesticides with zero residual limits are usually ban from use. Given that this would significantly distort our results, we have thus resorted to estimate in levels rather than using changes in MRLs.

2.3.2 Measure of EU Entry Price System

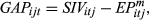

We constructed two distinct indicators at the bilateral level to capture the impact of EPS on Africa's exports. The first indicator is the corresponding duties imposed by the EU due to the price control. The Second indicator measures the difference between the import price of the product and the corresponding EP. We used the SIVs as proxy of the EU import price of the commodity, which is the imported price of the commodity excluding marketing and transportation costs and custom duties.

The first indicator is the calculation of the EP duties arising from the enforcement of the EPS by the EU on the three African export products considered in this study. For each product, the effectively applied daily EP duties measured in € per 100 kg were manually calculated. This sums up to about 365 data points in a year, resulting in a total of 2,192 data points per product, between 2008 and 2013. The daily ad valorem tariff equivalent of these duties was thereafter calculated using the ‘WTO agricultural method’. From this, simple yearly averages of the daily ad valorem tariff were calculated and used in our analysis. A priori, we expect that the EP tariff will have a negative impact on export flows.

(2)

(2)Cases of the SIV being above the maximum EP lead to a decrease in export price competitiveness, as the final price of the exports becomes more expensive relative to similar domestic goods, discouraging export purchases and thus inhibiting exports supply to the EU. However, cases in which the SIV is below the maximum EP means that EP duties would be incurred, thus making the final price of the exports to become more expensive. Adding in the EP duties to the synthetic import price (SIV) increases the final export price above the prevailing domestic price, thereby discouraging exports. Hence, either way, the coefficient will be negative. This will hold unless the entry price duty is such that when added to the SIV, the final price of the exported good is so small that it falls below the prevailing domestic prices, such that export product is still relatively cheaper than domestic goods. Alternatively, it would also hold if the prevailing SIV plus the duties is such that the final export price is still lower than the domestic price for the good (such that the home market is a dumping ground for the product). If these last two scenarios are the case, then, the coefficient of this variable will be positive a priori. Given this, the coefficient of this indicator could be negative, positive or even not statistically significant and the exact impact is an empirical question.

Although all exports products are subjected to EP control at the EU border, however, there exist differences in applicable EP duties and GAP among exporters. These variations are shown in Table 3. In the case of GAP, as depicted in column 2 of Table 3, we could observe negative values for Morocco and Egypt tomato exports while other exporters recorded positive values. This implies that for Morocco and Egypt, GAP < 0, their import prices in these products are below the maximum EP which brings about the imposition of entry duties which erode the price competitiveness of the exported goods. Relative to other African countries, Morocco is particularly very competitive in the production of tomatoes, making it to most often supply it below the stipulated entry prices. This consequently makes the country's tomato exports to attract relatively higher average entry price duties, which could have been higher if there had been no reduced (preferential) entry price duty enjoyed by Morocco from the EU. However, for other exporters, GAPijt ≥ 0, then, the import price is equal to or greater than the maximum EP, and the exporters are able to avoid the EP duties. Thus, even if the product attracts little or no duty, these exporters are less competitive relative to domestic producers due to the high import prices of their products.

| Products | African Countries | GAP | Ad valorem EP Duties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomatoes | Morocco | −19.15 | 126.21 |

| Egypt | −0.35 | 115.80 | |

| Others | 0.36 | 115.80 | |

| Limes and lemons | Morocco | 39.39 | 100.31 |

| South Africa | 43.43 | 100.21 | |

| Others | 39.19 | 100.19 | |

| Oranges | Morocco | 27.57 | 122.76 |

| South Africa | 27.84 | 100 | |

| Egypt | 21.16 | 124.26 | |

| Others | 29.44 | 103.39 |

Note

- Applicable duties vary all year round, so a yearly average is presented.

For all other products however, a positive value on the GAP variable is observed indicating that in most cases, on average these exports were supplied at import prices which are above the respective maximum entry prices. South Africa having the highest average value for limes and lemons and other countries have the highest value in the case of orange exports, indicating that these exporters supplied their products at a relatively higher prices than the others, which might erode their price competitiveness.

Furthermore, some differences also exist in the applicable EP duties across exporters. As depicted in column 4 of Table 3, Morocco has the highest EP duty for all products while South Africa has the least average EP duty in the case of oranges. In the case of Morocco, the trend depicted indicates that the country's exporters supply their products to the EU below the stipulated EP, attracting higher duties. However, exporters can also supply their products at the maximum possible price to the EU, so as to avoid the EP duties. For instance, South Africa has a comparative advantage in the production of oranges but has the least average EP duty in the case of oranges as it supplies its oranges to the EU at prices as close as possible to the maximum EP, making it to attract the lowest averaged EP duty.

3 Empirical Analysis

To investigate the trade impact of the two EU food regulations, we employ the gravity model which predicts that bilateral export between two countries is explained by economic masses of the trading countries and the geographical distance between them (Tinbergen, 1962; Pöyhönen, 1963).

3.1 Methodological Framework and Model Specification

The theoretical model for our analysis is based on firm heterogeneity behaviour which shows that due to the heterogeneous behaviour of firms, a small fraction of firms find it profitable to export, while others choose not to as they are less productive. Thus, this makes the trade matrix to contain both positive and zero trade flows. The intuition is that EU market conditions on food might affect the probability of African countries exporting to the EU, with productive firms exporting and non-productive firms choosing not to export.

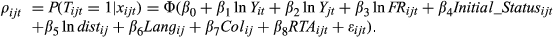

(3)

(3) is the probability that country i exports to country j, conditional on the observed variables; Tijt is a binary variable which is equal to one if country i exports to country j (Tijt = 1) and zero when it does not (Tijt = 0), where

is the probability that country i exports to country j, conditional on the observed variables; Tijt is a binary variable which is equal to one if country i exports to country j (Tijt = 1) and zero when it does not (Tijt = 0), where  and

and  are, respectively, the exporting and importing countries nominal GDP measured in US dollars.

are, respectively, the exporting and importing countries nominal GDP measured in US dollars.  is the EU food regulations which spans entry price conditions and food safety standards. These two measures of EU food regulations enter separately into equation 3 to disentangle their relative importance on Africa's exports potential.

is the EU food regulations which spans entry price conditions and food safety standards. These two measures of EU food regulations enter separately into equation 3 to disentangle their relative importance on Africa's exports potential.  is the geographical distance between countries i and j. Lang (common language), Col (colonial ties) and RTA (regional trade agreements) are dummy variables which take the value of one when both the exporting and importing countries share a common language and have colonial ties, belong to the similar trade agreement, respectively, zero otherwise; and

is the geographical distance between countries i and j. Lang (common language), Col (colonial ties) and RTA (regional trade agreements) are dummy variables which take the value of one when both the exporting and importing countries share a common language and have colonial ties, belong to the similar trade agreement, respectively, zero otherwise; and  is the idiosyncratic error term which is assumed to be well-behaved.

is the idiosyncratic error term which is assumed to be well-behaved.We had controlled for multilateral trade resistance terms which if omitted would lead to the ‘gold medal error’ and bias our estimates (Baldwin and Tagloni, 2006). A common approach of proxying the multilateral trade resistance terms in panel data is using time varying importer and exporter fixed effects (Feenstra, 2004; Baldwin and Taglioni, 2006). However, in this paper, we could not follow this approach due to the fact that standards have been harmonised in the EU since 2008 and thus, our variable on standards does not vary by importer and exporter but only vary over time. According to Head and Mayer (2014), in a gravity model setting with time varying importer and exporter dummies, the effect of an independent variable which does not vary by exporter, importer and time can no longer be identified. We therefore resorted to using another theoretically consistent method to control for the influence of MRT.

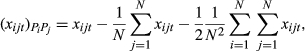

(4)

(4) to

to  in equation 3;

in equation 3;  is multilateral trade resistance terms.4 The first term on the right-hand side is the contribution of x to PiPj, and N is the number of bilateral observations on exports. The second term on the right-hand side is the simple average of gross trade costs facing exporter i across all importer j. The third term on the right-hand side denotes the simple average of all trade costs faced by importer j across all exporters. Table 4 provides the summary statistics of the variables included in our analyses.

is multilateral trade resistance terms.4 The first term on the right-hand side is the contribution of x to PiPj, and N is the number of bilateral observations on exports. The second term on the right-hand side is the simple average of gross trade costs facing exporter i across all importer j. The third term on the right-hand side denotes the simple average of all trade costs faced by importer j across all exporters. Table 4 provides the summary statistics of the variables included in our analyses.| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exporters’ GDP (Billion US Dollars) | 56.945 | 101.847 | 0.183 | 522.638 |

| Importers’ GDP (Billion US Dollars) | 1154.358 | 1031.872 | 8.099 | 3.634.820 |

| Export value (Million US Dollars) | 0.124 | 1.025 | 2.20e-08 | 17.371 |

| Entry Price Duty_Tomatoes | 116.165 | 4.411 | 108.311 | 135.190 |

| Entry Price Duty_Oranges | 104.863 | 14.872 | 100 | 220.157 |

| Entry Price Duty_Limes and Lemons | 100.191 | 0.268 | 100 | 100.827 |

| Entry Price Gap_Tomatoes | −0.534 | 7.494 | −31.795 | 24.832 |

| Entry Price Gap_Oranges | 28.968 | 3.433 | 17.815 | 36.522 |

| Entry Price Gap_Limes and Lemons | 39.356 | 17.746 | 13.819 | 73.340 |

| EU Pesticide Standards_Tomatoes | 0.620 | 0.025 | 0.587 | 0.652 |

| EU Pesticide Standards_Oranges | 0.585 | 0.021 | 0.559 | 0.616 |

| EU Pesticide Standards_Limes and Lemons | 0.606 | 0.214 | 0.580 | 0.641 |

| Distance | 4792.335 | 1969.561 | 375.723 | 9693.590 |

| Language | 0.219 | 0.414 | 0 | 1 |

| Colonial Ties | 0.105 | 0.307 | 0 | 1 |

| RTA | 0.191 | 0.393 | 0 | 1 |

3.2 Estimation Strategy

Our strategy is to model the binary decision of exporter to either export or not to the EU using the random-effects probit model. A major reason for the preference for the random-effects probit model is due to little variation in one of our main variable of interest. In many cases, MRLs of pesticides allowed in most food products only change by a small unit (e.g. changing from 0.01 to 0.02), and at times, it does not change. Hence, by default, there is little within variation in pesticide standards, requiring the use a random-effects model as opposed to a fixed-effects probit model. This justifies our preference for the random-effects probit model.

There are however some limitations in using random-effects over the fixed-effects model in the gravity model, particularly, in the case of linear panel data models. This is illustrated in the three arguments put forward by Egger (2000). First, most of the explanatory variables in a gravity model are not random but are instead associated with some political, geographical and historical relationships; thus, a fixed-effects model may be a preferred choice from an intuitive point of view. Second, in the typical gravity model, interest is usually in obtaining trade estimates for some predetermined selection of countries and not for some randomly drawn samples of country pairs, which might make the fixed-effects model the preferred choice. Third, the random-effects model will only give unbiased and consistent estimates if the explanatory variables are uncorrelated with the error term. A violation of this assumption is in favour of the fixed-effects model which would then give consistent and efficient estimates in the gravity model.

Nevertheless, the above arguments are fundamentally different in the case of non-linear models particularly limited dependent variable models such as the probit model. One important reason is that when the fixed effects is used with the probit model, the maximisation of the probit model's likelihood function suffers from the incidental parameters problem (Neyman and Scott, 1948). The incidental parameters problem arises because when a fixed-effects non-linear estimator is used to estimate a model that has its parameters specified to include individual-specific effects, inconsistent estimates of the parameters would be produced if time period (t) is fixed (Arellano, 2003; Greene, 2004). This is because the number of parameters (including the individual-specific dummies) increases with the number of observations, and the shorter the time period, the larger the inconsistency (Verbeek, 2000; Greene, 2004). This undermines the consistency feature, which is the usual justification for using the fixed-effects estimator. This is however not a problem in fixed-effects linear models as the problem is usually overcome using appropriate transformation such as differencing to eliminate the individual effects from the model. Differencing is also problematic in the context of non-linear models, since only the observations that change status can be used to estimate a fixed-effects probit and hence, only a restricted sample can be used. Consequently, the random-effects probit maximum-likelihood model is preferred.

More so, the consistency of the fixed-effects probit hinges on t being large (Greene, 2004). However, since in many applications t is fixed and usually small, the fixed-effects probit estimator of the individual-specific effects does not converge and gives inconsistent estimates (Greene, 2004) and the bias persists even as t increases (Hahn and Newey, 2004). In addition, as noted by Greene (2004) in a Monte Carlo study of fixed-effects estimators using a variety of non-linear models, the fixed-effects probit estimator exhibits large small sample bias and the biasedness is still large and persistent as the sample size increases. In other words, there exist no consistent estimates in the case of a fixed-effects probit model because the model ignores the presence of the individual-specific effects in the panel data (Verbeek, 2000; Greene, 2004). All of these motivate our choice of the random-effects probit model over the fixed-effects probit model.

3.3 Data Sources

Our data set covers bilateral exports from selected African countries to the EU countries that are major trading partners between 2008 and 2013.5 A list of countries included in the analysis is available in the Appendix. Bilateral exports data were extracted from UN COMTRADE via the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITs) database at the Harmonised System digit 6 level. This covers three unique datasets on African exports of tomatoes (070200), oranges (080510), and limes and lemons (080550) to the EU. Data on distance, language and colony were collected from the Centre d'Etudes Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII) database; GDP data were from the World Bank World Development Indicator, while data used in constructing the regional agreement dummy were from the World Trade Organisation. Data on pesticide standards were manually collated online from the EUROPA database which houses a rich database of all pesticide standards developed and adopted by all EU Member States between 2008 and 2013. Data on EU EP measures and duties in euros were manually collated from EC TARIC website and were converted to US dollars using exchange rate data from the 2014 World Development Indicators. The ad valorem equivalents of the entry price duties were calculated using the WTO agricultural method based on trade data from UN COMTRADE. Daily data on country specific standard import values on each product set by the EC results obtained from the daily EC journals (various issues).

4 Results and Discussion

The results of our probit equation estimated separately for the three unique datasets on tomatoes, limes and lemons, and oranges are presented in this section. All models are estimated using random-effects probit model with robust standard errors clustered across panels (exporter–importer–year). The reported estimates are the marginal effects of the probit model.

Our strategy is to disentangle the relative importance of the two measures of EU food regulations on Africa's exports potential. Thus, the two policy measures entered separately into equation 3. We have previously empirically tested the appropriateness of either estimating the two policy variables together in one single regression (the unrestricted model) or running them separately in two separate regression models (the restricted model). Since the unrestricted model is nested in the restricted model, we used the likelihood ratio test which is popularly used in choosing between nested models. The result of the likelihood ratio test produced insignificant test statistic of 3.72 with a corresponding p-value of 0.1557, and thus, we could not reject the null hypothesis that the restricted model is more appropriate. This prompted us to introduce the policy variables in separate regression models.

4.1 Impacts of EU Food Safety Standards on Africa's Exports

Table 5 presents the results of the estimation of EU pesticide standards on African exports of the three selected products. The main results indicate that standards imposed by the EU on these products are barrier to Africa's export penetration. For all three products, regulated EU pesticide standards turn out to be positive and significant, implying that standards have a direct relationship with exports such that a decrease in the standard (increase in the stringency of the pesticides standards) decreases the probability of exporting all three products to the EU. The average marginal effect on the probability of exporting is 6 per cent for tomatoes, 7 per cent for limes and lemons, and 4 per cent for oranges and these are all on the prohibitive side. Our result confirms those of Wilson and Otsuki (2004), Chen et al. (2008) and Winchester et al. (2012), all authors find that pesticide standards can inhibit export penetration, and more recently by Xiong and Beghin (2014) and Ferro et al. (2015) who find that pesticide standards hinder the likelihood of trade mainly through the extensive margin, particularly for developing countries.

| Variables | Tomatoes | Limes and Lemons | Oranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exporters GDP | 0.095 | 0.249** | 0.080 |

| (0.095) | (0.109) | (0.090) | |

| Importers GDP | 0.260* | 0.629*** | 0.572*** |

| (0.134) | (0.234) | (0.128) | |

| EU Pesticide Standards | 6.004*** | 6.885*** | 4.012*** |

| (1.509) | (1.541) | (1.224) | |

| Initial Status | 1.097*** | 0.546** | 0.554*** |

| (0.252) | (0.255) | (0.193) | |

| Distance | −3.898** | −2.896* | −2.851*** |

| (1.607) | (1.554) | (0.893) | |

| Colony | 0.170 | 2.876** | 1.637** |

| (0.239) | (1.153) | (0.823) | |

| Language | 2.197*** | 1.028 | 2.867*** |

| (0.698) | (0.841) | (0.684) | |

| RTA | 0.253 | 0.593 | 1.138** |

| (0.568) | (1.218) | (0.495) | |

| Constant | −12.23*** | −26.34*** | −19.29*** |

| (3.805) | (6.520) | (4.235) | |

| Observations | 1,176 | 1,248 | 1,050 |

Notes

- (i)Reported coefficients are average marginal effects of probit model.

- (ii)Clustered robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered by importer, exporter and year.

- (iii)***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

This result is as expected since as high as 70 per cent of Africa's fruit and vegetable products were rejected by the EU between 2008 and 2013 for exceeding EU pesticide residue limits (EC RASFF, 2014). Furthermore, these products are part of the list of pesticide-contaminated fruits and vegetables that retain high levels of pesticide residues and are more likely to test positive for the presence of multiple pesticides in them (EWG, 2013). Thus, these products attract the most stringent standards to protect consumers, implying additional fixed costs to comply with them, which might be too much to bear for the small-scale producers, most of which constitute exporters of this product in Africa. In addition, the EU has been extending technical assistance to some farmers, producers and exporters in Africa, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries to enable them satisfy its safety standards and access EU markets. Two such development cooperations are the Europe-Africa-Caribbean-Pacific Liaison Committee and Pesticide Initiative Programme both of which have been supporting ACP fruit and vegetable sectors to maintain or increase the contribution of horticultural export on poverty reduction. However, potential exporters have not been able to benefit from such assistance and this could possibly explain their low potential to export to the EU and why standard constitutes a significant market access problem for them.

On the supply side, the economic masses of African countries proxied by their GDPs do not significantly encourage the exportation of these products except for limes and lemons. This is in spite of the fact that Africa produced between 10 to 13 per cent and 7 to 11 per cent of total world export of tomatoes and oranges, respectively, in the last two decades (FAOSTAT, 2014). Similar results were obtained by Mayer and Fajarnes (2008), Xiong and Beghin (2011) and Kareem et al. (2015) who confirmed that domestic market constraint such as countries’ sizes constitute a major constraint to Africa's export penetration. Our results indicate that the exporting African countries income allocated to agriculture has not been significant in luring new exporters into this trade, thereby constituting an important constraint to initiating new trade relationships. An exception is lime and lemon exports where we see that African countries’ income or productive capacity has been able to enhance the probability of exporting these products to the EU, such that a 1 per cent increase in the income base of Africa has increased the probability of exporting to the EU by 0.25 per cent. However, this productive capability is still low relative to the income growth the continent is experiencing in recent years.

In contrast, on the demand side, the absorptive capacity of EU consumers measured by EU countries’ GDP is able to stimulate new trade, for all three products. However, the value is relatively low for tomatoes. One plausible reason for this is the unwillingness of EU consumers to consume conventional tomatoes and their increased preference for organic products. Nevertheless, this positive absorptive capacity of the importing countries in contrast with the weak productive capacity of the exporting countries, indicates that a continuous promotion and expansion of this commodity is needed to meet the relative high import demand and harness immense benefits from trade.

Regarding the other control variables, most of them are significant with the expected signs. Africa's probability of exporting to the EU depends largely on whether the product was already exported in the initial period (initial_status). In other words, products already exported in year 2008 (which is the start of the harmonisation of EU food regulations) have high probabilities of being exported in subsequent years. In relation to other trade costs, distance hinders the exports of the three products to the EU. In addition, the probability of exporting these products turns out to depend largely on sharing common language and colonial ties with the EU. However, common language between the two trading partners has no apparent impact on the decision to export limes and lemons to the EU, while in the case of tomatoes, colonial ties between the country pairs actually reduces the probability of trading.

In addition, having a trade agreement relationship with the EU is a stimulating factor for potential African exporters in establishing possible new trade relationship, significantly impacting on Africa's probability of exporting oranges to the EU. It has however no apparent effect on tomato as well as lime and lemon exports to the EU, which means that RTAs should be negotiated product by product and not at the aggregated level. However, one possible explanation for this is that regional trade agreements with the EU would not increase trade unless these exporting countries comply with EU pesticides standards, which is applied on an MFN basis. This aside, the benefits from all the RTAs between Africa and the EU have been in form of preferential tariff to selected African countries while non-tariff measures are applied on an MFN6 basis with no preferential treatment even for countries in RTA relationships with the EU. This could thus explain why standard as a non-tariff measure constitutes a significant market access problem for Africa.

4.2 Impacts of EU Entry Price Conditions on Africa's Exports

We now turn to investigate the effect of the second market access variable on the potential of generating export relationship with the EU. In relation to our market access variables, the estimates reported in Table 6 indicate that the EU EP duty does not significantly affect the probability of exporting except for the case of tomatoes. More specifically, the coefficient on the ad valorem EP duties tomato exporters incurred from supplying their products below EU EP is significant and negative, implying that EP duties represent an important market access barrier for these potential tomato exporters. In essence, supplying tomatoes to the EU below the predetermined EP by 1 per cent brings about the imposition of duties which significantly decrease the probability to trade with the EU by as high as 14 per cent. This is expected since EP duties would be incurred as a penalty factor when the import price is below the maximum EP, thus making cheaper exports more expensive and less competitive in the EU markets. Consequently, the additional entry price duties increase the final import price above the prevailing domestic price in the EU, thereby discouraging exports and might force exporters to look for other markets and abandon the EU market, as the EU EPS inhibits trade much more than the regulated EU pesticide standards.

| Variables | Tomatoes | Lime and Lemon | Oranges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exporters GDP | 0.144 | 0.314*** | 0.117 |

| (0.098) | (0.110) | (0.091) | |

| Importers GDP | 0.242* | 0.527*** | 0.538*** |

| (0.130) | (0.197) | (0.118) | |

| Entry Price Duty | −14.160*** | −28.280 | 0.577 |

| (5.113) | (18.25) | (0.430) | |

| Entry Price Gap | −0.089*** | −0.002 | 0.017 |

| (0.031) | (0.002) | (0.012) | |

| Initial status | 1.026*** | 0.480* | 0.537*** |

| (0.241) | (0.250) | (0.183) | |

| Distance | −3.699** | −2.731* | −2.739*** |

| (1.536) | (1.414) | (0.866) | |

| Colony | −0.596** | 2.616** | 1.648** |

| (0.242) | (1.052) | (0.823) | |

| Language | 2.119*** | 0.986 | 2.759*** |

| (0.691) | (0.757) | (0.655) | |

| RTA | 1.063 | 1.316 | 2.201** |

| (0.653) | (1.259) | (0.864) | |

| Constant | −12.74*** | −24.74*** | −19.16*** |

| (3.768) | (5.663) | (4.104) | |

| Observations | 1,176 | 1,248 | 1,050 |

Notes

- (i)Reported coefficients are average marginal effects of probit model.

- (ii)Clustered robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered by importer, exporter and year.

- (iii)***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

On a related note, the second indicator of EU EPS (entry price GAP) which measures the competitiveness of Africa's import price of tomatoes supplied by Africa relative to domestic growers’ is also statistically significant and negative, showing that the imposition of the entry price erodes Africa's price competitiveness. In fact, a dollar increase in Africa's price of importing tomatoes above the EU maximum EP reduces exports by 9.3 per cent (that is e0.089 − 1 × 100). The increase of the import price of tomatoes above the EP brings about the imposition of additional duties, which erodes the price competitiveness of tomato exports. This leads to a decrease in export volume, as the final price of the exported good becomes more expensive relative to EU domestic prices, discouraging export purchases and creating market access problem for potential tomato exporters. Similar results were found by Chemnitz and Grethe (2005) on Morocco tomato exports to the EU and by Goetz and Grethe (2010) on China's exports of apples and pears to the EU.

However, in the case of limes and lemons as well as oranges, the trade impacts of the two variables capturing the EU EPS are statistically indistinguishable from zero. This indicates that the EU EPS shows no apparent effects on these products and thus is not be relevant for these exporters in establishing new trade relationship with the EU or extending their products to new markets in the EU. More specifically, the first variable, which is the EP duty, is insignificant and thus irrelevant to export penetration Africa's export market access to the EU. One plausible explanation for this might be that most of these exporters are already producing at competitive prices at home, as they have relative comparative advantage in the production of these commodities due to a tropical climate which favours their production all year round. Thus, most of the countries produce at relatively lower costs compared to the EU growers such that no amount of extra duties incurred could discourage them from exporting to the EU. Consequently, the imposition of the EU EP duties on these products does not erode their price competitiveness; the import price is already highly competitive such that no stipulated amount of additional ad valorem tariff can erode such competitiveness. In fact, the EP is of no relevance to them in their decision to export or not to export to the EU.

Complementarily, the second variable (entry price GAP) is also not a significant market access problem for trade in limes and lemons as well as oranges. One possible explanation of this result is that plausibly, the exporters already have competitive cost advantage over EU growers and thus are supplying oranges at the lowest possible price while complying with the EP such that they are able to avoid paying the EP duties. Thus, this result implies that for limes and lemons as well as oranges exports, the EU EPS is not relevant in the decision to enter new trade relationship with the EU, while the EU's stringent pesticide standards is a more problematic factor in penetrating EU markets. Similar results were reported by Goetz and Grethe (2007) who found EU EP control is of low importance for exports of oranges from selected Mediterranean countries to the EU. Our results also confirm those of Cioffi and dell’ Aquila (2004) regarding Southern exporters to the EU.

Turning to the control variables, the estimates in Table 5 show that importers’ GDP and initial status are the major factors driving African exporters’ possibility of establishing new trade relationships with the EU.

5 Robustness Check

We engage in robustness check to assure the reliability of our results. Our paramount concern is whether our results are driven by the characteristics of the exporting countries. For instance, standards and entry price control may be restrictive for some of the countries but may not be restrictive for exporters of higher income countries such as Morocco and South Africa. To address this concern, we have re-estimated the model excluding Morocco and South Africa as they are two important countries with huge economic growth in Africa given our datasets.

The results of estimating the model excluding these two countries are presented in Table 7. They are similar to those obtained in Tables 5 and 6 in terms of the impact of the two non-tariff measures, particularly for the cases of tomatoes and oranges. These results further highlight our previous conclusion although the coefficients of the target variables are slightly lower in magnitude. Nevertheless, the basic message of this study in relation to the impact of the two non-tariff measures remains largely unchanged. An exception is the coefficient on EP variable in the case of limes and lemons, which now turned negative and statistically significant indicating that on average the EP is more restrictive for all the other African countries in the dataset than they are for exporters of well-performing higher income countries such as Morocco and South Africa.

| Variables | Pesticide Standards | Entry Price System | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tomatoes | Lime and Lemon | Oranges | Tomatoes | Lime and Lemon | Oranges | |

| Exporters GDP | 0.122 | 0.295** | 0.111 | 0.208* | 0.379*** | 0.153 |

| (0.108) | (0.129) | (0.099) | (0.114) | (0.133) | (0.099) | |

| Importers GDP | 0.223 | 0.642** | 0.568*** | 0.213 | 0.530** | 0.536*** |

| (0.142) | (0.259) | (0.130) | (0.138) | (0.211) | (0.121) | |

| EU Pesticide Standards | 6.635*** | 7.446*** | 4.037*** | |||

| (1.696) | (1.709) | (1.310) | ||||

| Entry Price Duty | −18.468*** | −41.945** | 0.507 | |||

| (5.438) | (18.433) | (0.458) | ||||

| Entry Price GAP | −0.113*** | −0.002 | 0.019 | |||

| (0.033) | (0.003) | (0.013) | ||||

| Initial status | 1.143*** | 0.650** | 0.494** | 1.107*** | 0.566** | 0.490** |

| (0.276) | (0.276) | (0.204) | (0.263) | (0.264) | (0.195) | |

| Distance | −5.670*** | −2.759 | −3.826*** | −5.287*** | −2.588 | −3.673*** |

| (1.909) | (2.625) | (1.186) | (1.761) | (2.336) | (1.160) | |

| Colony | 0.229 | 3.455** | 2.128** | −0.627** | 3.055** | 2.125** |

| (0.259) | (1.442) | (0.890) | (0.258) | (1.242) | (0.889) | |

| Language | 2.393*** | 1.051 | 2.845*** | 2.305*** | 0.974 | 2.738*** |

| (0.742) | (0.917) | (0.694) | (0.736) | (0.806) | (0.662) | |

| RTA | 0.287 | 0.508 | 1.139** | 0.845 | 1.327 | 2.110** |

| (0.596) | (1.244) | (0.508) | (0.605) | (1.315) | (0.835) | |

| Constant | −12.055*** | −28.141*** | −19.908*** | −13.589*** | −26.548*** | −19.961*** |

| (4.042) | (7.613) | (4.456) | (4.136) | (6.410) | (4.356) | |

| Observations | 1,092 | 1,152 | 966 | 1,092 | 1,152 | 966 |

Notes

- (i)Reported coefficients are average marginal effects of probit model.

- (ii)Clustered robust standard errors are in parentheses, clustered by importer, exporter and year.

- (iii)***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

6 Conclusion and Policy Implications

This study investigates the impact of two non-tariff aspects of EU food regulations on tomato, oranges and lime and lemon exports to the EU. Our results have several implications for stimulating exports and encouraging potential exporters in Africa. Our main results show that EU standards inhibit exporters’ probability to export to the EU for all three products. In addition, we found the EU EP control to have no apparent effect on potential African exporters of oranges and limes and lemons, but exert significant negative influence on their probability of exporting tomatoes to the EU. Our results also indicate government's neglect of promoting and expanding the production of these export products, given the low magnitude and or insignificant sign of the exporters’ GDP obtained in most cases. This points out that apart from market access problem, the root of Africa's marginalisation in world trade is multiple, indicating that fostering the continent's integration with the global economy will require policies targeted at removing both domestic supply constraints and ensuring external demand for the continent's exports.

This study finds that standards can indeed act as impediment to initiating export relationship with the EU. However, according to Jaffee and Henson (2004), this is not always the case as increased and tightening of standards can also serve as catalysts for poor countries to participate in international trade, if such countries adhere to the standards set by importing countries. Numerous technical and financial assistances are being extended by the EU and United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) to selected African exporters to assist them in complying with stringent standards and also prepare them for export markets. These assistances have helped exporting countries to upgrade their supply capacities to fit importing countries standards, to reposition themselves in competitive international markets and enhance market access (Jaffee and Henson, 2004). Thus, such assistances should also be extended to potential exporters and should be targeted to ensure compliance with EU standards and prepare them for exporting to the EU so as to reap maximum economic benefit.

More importantly, trade negotiations with the EU should include the provision of sophisticated technological and scientific assistance to Africa's agricultural sector, particularly to small-scale producers that dominate the scene, so as to assist them in complying with EU standards and enhance continuous market access for the continent. In addition, agreements with the EU negotiated to ensure the provision of preferential EPS for African countries, to enable them maintain their competitiveness in the EU markets is an important policy imprint for the African policymakers. At the country level, policy should be channelled towards the removal of domestic market constraints, which will increase production for exports. This could be achieved through a wholehearted commitment to the implementation of strong regulatory framework and the development of strong institutions that would boost country-level capacity to satisfy food safety requirements. All these blueprints need to be faithfully implemented for trade to serve as a promising avenue to boost economic growth for the continent.

Appendix A

| Country Groups | Members |

|---|---|

| Importers (EU) | Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain |

| Exporters (Africa) | Algeria, Angola, Cape Verde, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt Arab Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Liberia, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo |

| Country Groups | Members |

|---|---|

| Importers (EU) | France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain |

| Exporters (Africa) | Algeria, Angola, Benin, Cape Verde, Congo Republic, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa |

| Country Groups | Members |

|---|---|

| Importers (EU) | Belgium, France, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain |

| Exporters (Africa) | Algeria, Angola, Benin, Cape Verde, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, Congo Republic, Egypt Arab Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Nigeria, Sao Tome and Principe, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo |