Comparing a point-of-care urine tenofovir lateral flow assay to self-reported adherence and their associations with viral load suppression among adults on antiretroviral therapy

Results of this study were presented as an oral abstract at virtual CROI 6–10 March 2021.

The point-of-care urine tenofovir lateral flow assays were donated by Abbott. Abbott provided training on use of the test but did not participate in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of results, or writing the manuscript.

Sustainable Development Goal: Good Health and Wellbeing

Abstract

Background

Point-of-care (POC) lateral flow assays (LFA) to detect tenofovir (TFV) in urine have been developed to measure short-term ART adherence. Limited data exist from people living with HIV in routine care.

Methods

Adults on TFV-containing regimens, having a routine viral load (VL) at an HIV clinic in Cape Town, South Africa were enrolled in a cross-sectional study. Patients recalled missed ART doses in the past three and 7 days and urine was tested using a POC TFV LFA. VL on the day was abstracted from medical records.

Results

Among 314 participants, 293 (93%) had VL <1000 copies/mL, 20 (6%) had no TFV detected and 24 (8%) reported ≥1 missed dose in the past 3 days. Agreement between VL ≥1000 and undetectable TFV was higher compared to 3-day recall of ≥1 missed dose (Kappa 0.504 vs. 0.163, p = 0.015). The AUC to detect VL ≥1000 was 0.747 (95% CI 0.637–0.856) for undetectable TFV. This was statistically significantly better than for 7-day recall (0.571 95% CI 0.476–0.666, p = 0.040) but not for 3-day recall (0.587 95% CI 0.492–0.681, p = 0.071) of ≥1 missed dose.

Conclusion

In this largely virally suppressed cohort, TFV in urine had better agreement with VL than self-reported adherence and was a better predictor of viraemia on two of three self-report measures. Used in combination with VL, the POC urine TFV LFA could flag patients with viraemia in the presence of ART. Further research is needed to understand the potential application in different populations on ART, including pregnant women.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, 38.4 million people were living with HIV (PLHIV) and 28.7 million PLHIV were accessing antiretroviral therapy (ART) in 2021 [1]. The scale-up of ART has been hugely successful in reducing HIV viral load and in turn, reducing the risk of HIV transmission [2]. Ongoing adherence to ART is essential to maintain viral suppression and avoid treatment resistance. However, accurate measurement of ART adherence is a major challenge, particularly in resource-limited, routine care settings.

Traditional real-time methods of measuring adherence such as self-report and pill counts are known to be unreliable. Self-reported adherence is prone to bias and usually overestimates treatment adherence [3]. Pill counts are also commonly used but pills can be discarded by patients prior to their clinic visits, making the patient appear more adherent than they have been [4]. Objective measures such as electronic drug monitoring devices have been used in research settings but are seldom used in routine care and are also subject to interference. The measurement of antiretrovirals in biological specimens is an objective and reliable adherence measure, however, laboratory assays are expensive and time-consuming as they often require processing outside the clinic setting [5]. Tenofovir-diphosphate in dried blood spots is considered the current state-of-the-art adherence measure in clinical research but it still requires a complex and expensive laboratory-based assay and is not feasible for use in most routine care settings. There is thus an urgent need for a real-time measure of ART adherence that is both objective and can be administered at the point of care. Newer antibody-based technologies allowing antiretroviral detection in urine are less costly and can provide rapid, objective, point-of-care (POC) adherence measures [5].

A POC lateral flow assay (LFA) to detect tenofovir (TFV) analytes in urine was developed and validated among HIV-negative patients on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [6, 7]. The POC urine TFV LFA is designed to provide a qualitative (TFV present or absent) result using a threshold of 1500 ng/mL. This threshold provides a robust short-term adherence measure with 98% sensitivity to detect doses taken in the past 24 h [8]. The POC urine TFV LFA also allows for real-time objective measurement of short-term adherence to ART among PLHIV. While this POC test may have great implications for HIV treatment and prevention, there are few data from PLHIV on ART and it is not yet clear how the test can best be used in routine clinical care. In this study, we evaluated the POC urine TFV LFA test compared to self-reported ART adherence questions, and their association with HIV viral load among PLHIV attending routine HIV services in Cape Town, South Africa.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional evaluation at a large primary healthcare clinic that provides routine ART services in Gugulethu, Cape Town. Any PLHIV attending routine care services at the clinic and who was having a viral load test done on the day of the visit was eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients were recruited from the main ART clinic (males and non-pregnant females) and from the antenatal clinic (pregnant females). Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years, being on ART for less than 3 months (to allow a window in which viral suppression could be achieved after ART initiation), and not currently taking a tenofovir-containing ART regimen. Only tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and not tenofovir alafenamide, is available in the public sector in South Africa.

Patients were approached during their routine visit and invited to participate. Those who were eligible and agreed to participate were enrolled in the study. Study procedures included a short questionnaire collecting demographic information, HIV and ART history, and self-reported ART adherence. Participants were asked to provide a urine sample that was immediately tested using the POC TFV LFA. HIV viral load (in copies/mL) and creatinine (in mg/dL) from the day of the study visit were abstracted from routine medical records. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) and the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology (CKD-Epi) equations accounting for participant race, sex, and age. However, it is noted that the accuracy of these estimates in pregnant women is limited.

Lateral flow assay urine tenofovir test

The Abbott POC urine TFV LFA (developed by Dr Monica Gandhi's research group [6, 8]) is a strip test that indicates the presence or absence of ‘adequate’ tenofovir in the urine at a threshold of 1500 ng/mL, based on levels after no ART taken for >48 h. The LFA was developed and tested among HIV-uninfected adults taking pre-exposure prophylaxis. It was found to have 97% specificity and 99% sensitivity when compared to the gold standard measure of tenofovir levels using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

This POC TFV LFA costs less than $2 a strip and is easy to perform and interpret. A urine specimen (2–3 drops) is applied to the sample pad and is then drawn through the strip by capillary action on a nitrocellulose membrane. The test pad contains coloured particles labelled with TFV-specific antibodies, as well as a test strip of TFV antigen and a control strip. Free tenofovir in the urine binds the tenofovir antibodies, preventing them from reaching the tenofovir antigen strip and resulting in no coloured test line if there is sufficient TFV in the urine specimen. If no or insufficient TFV is present in the urine, the TFV antibodies in the strip will migrate with the urine to the antigen strip, resulting in a coloured test line. Therefore, specimens that are negative for TFV will display a coloured test line while those positive for TFV will not. The result can be read within 5 min and is recorded as a binary variable (TFV detected or not detected).

Self-reported adherence

In the study questionnaire, participants were asked to report on ART doses taken in the past 7 days. Three binary self-reported adherence indicators were calculated to capture short-term medication taking: (1) ≥1 missed dose in the past 3 days, (2) ≥1 missed dose in the past 7 days, and (3) ≥2 missed doses in the past 7 days. Short-term missed dose recall is a common self-reported adherence metric [9, 10]. We included ≥1 missed dose in the past 3 days to try to capture the period covered by the POC TFV LFA, and ≥1 and ≥2 mossed doses in the past 7 days as alternatives. Due to overall high self-reported adherence and limited variability in reported missed doses, we were not able to examine other definitions such as no doses in the past 3 days.

HIV viral load

Venous blood for HIV RNA viral load testing was drawn in the routine services and specimens were tested by the National Health Laboratory Service. Results of the viral load tests done on the day of the study visit were abstracted from the routine medical record as soon as they were available. Viral load thresholds of ≥1000 copies/mL were used in primary analyses.

Analysis

The characteristics of the study sample were described with frequencies and proportions for categorical variables and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for numeric variables. Agreement between viral load ≥1000 copies/mL, self-reported adherence indicators, and POC TFV LFA result was calculated using Cohen's Kappa and reported as kappa statistics (where 1 indicates perfect agreement and values close to 0 indicate very poor agreement) with p-values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) [11, 12]. Kappa statistics for the agreement between self-reported adherence measures and viral load ≥1000 were compared to Kappa statistics for POC TFV LFA and viral load ≥1000 using paired t tests with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons. In addition, agreement between self-reported adherence measures and POC TFV LFA results was calculated in sub-groups of males, non-pregnant females, and females.

Diagnostic characteristics were calculated for the POC TFV LFA and each of the self-reported adherence indicators to detect viremia on the same day. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated with 95% CI. Likelihood odds ratios (OR) and the area under Receiver Operating Characteristics curves (AUC) were calculated with 95% CI. The AUC for each self-reported adherence measure was compared with that for the POC urine TFV LFA with p-values adjusted for multiple comparisons. Diagnostic characteristics were also calculated in sex and pregnancy sub-groups. In secondary analyses, diagnostic characteristics were calculated stratified by time since ART initiation (<2 years versus ≥2 years) and using a viral load threshold of ≥50 copies/mL. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.2 and R version 3.6.3. Statistical tests were all two-sided at α = 0.05.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

RESULTS

Between February and November 2020, 352 PLHIV were recruited from routine ART services at the Gugulethu Community Health Centre. One patient was unable to provide a urine sample and was excluded. No invalid results on the POC TFV LFA were obtained. There were 37 patients for whom the viral load test results from the day of the study visit were not obtained and this analysis includes 314 participants who had both POC TFV LFA and viral load test results available.

Description of study sample

The study sample included 66 males (21%), 178 non-pregnant females (57%), and 70 pregnant females (22%). Median time on ART was 6 years (IQR 3–10) and median age was 38 years (IQR 33–45). Pregnant women were younger (median age 32 [IQR 29–37]) with fewer years on ART (median 4 years [IQR 2–7]) compared to males and non-pregnant females (Table 1). Almost all participants (94%) were on a first-line regimen of TDF, efavirenz (EFV), and either lamivudine (3TC) or emtricitabine (FTC). The remaining 6% were on other TDF containing regimens including dolutegravir-TDF-FTC, lopinavir-ritonavir-TDF-FTC, atazanavir-ritonavir-TDF-FTC, nevirapine-TDF-FTC. Overall, 14% of participants (n = 42) reported having comorbidities, predominantly hypertension (n = 37) and diabetes (n = 6). Comorbidities were more common among males and non-pregnant females compared to pregnant females. Weight and creatine data were only available for 236 (75%) and 287 (91%) participants, respectively. Using both the MDRD and CKD-Epi formulae, eGFR was >90 mL/min/1.73 m2 in more than 90% of all participants. No participants had more than mildly decreased eGFR.

| Total | Male | Non-pregnant female | Pregnant female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 314 | 66 (21%) | 178 (57%) | 70 (22%) |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 38 (33–45) | 45 (37–52) | 39 (34–45) | 32 (29–37) |

| Median years on ART (IQR) n = 310a | 6 (3–10) | 7 (3–10) | 7 (4–10) | 4 (2–7) |

| <2 years | 61 (20) | 16 (24) | 25 (14) | 20 (29) |

| ≥2 years | 249 (80) | 50 (76) | 149 (86) | 50 (71) |

| Any comorbidity | 42 (13) | 10 (15) | 31 (17) | 1 (1) |

| Hypertension | 37 (12) | 8 (12) | 28 (16) | 1 (1) |

| Diabetes | 6 (2) | 2 (3) | 4 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Tuberculosis | 3 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Median weight (kg) at the visit (n = 236) | 75 (65–90) | 71 (62–78) | 77 (64–90) | 80 (70–101) |

| Median serum creatinine at the visit (mg/dL, n = 287) | 0.67 (0.57–0.80) | 0.97 (0.81–1.03) | 0.66 (0.59–0.75) | 0.52 (0.47–0.60) |

| Median MDRD GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 125 (106–146) | 107 (99–129) | 123 (106–138) | 166 (138–178) |

| Normal/high (≥90) | 269 (94) | 57 (90) | 150 (93) | 62 (100) |

| Mildly decreased (60–89) | 18 (6) | 6 (10) | 12 (7) | 0 |

| Median CKD-Epi (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 130 (113–140) | 111 (101–127) | 127 (114–135) | 148 (139–154) |

| Normal/high (≥90) | 271 (94) | 56 (89) | 153 (94) | 62 (100) |

| Mildly decreased (60–89) | 16 (6) | 7 (11) | 9 (6) | 0 |

- a Four non-pregnant females missing ART initiation date.

Description of adherence and viral load

Overall, levels of adherence on all study measures were high (Table 2). Only 6% of participants had no TFV detected in urine. The proportion with no TFV detected was higher among pregnant females (17%) compared to males (5%) and non-pregnant females (3%). This pattern was also observed for viral load ≥1000 copies/mL (16% of pregnant females compared to 5% and 4% of males and non-pregnant females, respectively) but the proportion with ≥50 copies/mL were more similar (23% of pregnant females compared to 20% and 15% of males and non-pregnant females, respectively). More than 85% of all participants in all sub-groups reported no missed ART doses in the past 3 and 7 days (Table 2).

| Total | Male | Non-pregnant female | Pregnant female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 314 | 66 (21) | 178 (57) | 70 (22) |

| Urine LFA | ||||

| TFV present | 294 (94) | 63 (95) | 173 (97) | 58 (83) |

| TFV absent | 20 (6) | 3 (5) | 5 (3) | 12 (17) |

| Self-reported adherence | ||||

| Missed doses in the past 3 days | ||||

| No doses missed | 290 (92) | 59 (89) | 170 (96) | 61 (87) |

| 1 or more doses missed | 24 (8) | 7 (11) | 8 (4) | 9 (13) |

| Missed doses in the past 7 days | ||||

| No doses missed | 282 (89) | 58 (88) | 162 (91) | 61 (87) |

| 1 or more doses missed | 33 (11) | 8 (12) | 16 (9) | 9 (13) |

| <2 doses missed | 299 (95) | 63 (95) | 172 (97) | 64 (91) |

| 2 or more doses missed | 15 (5) | 3 (5) | 6 (3) | 6 (9) |

| Viral load | ||||

| <50 copies/mL | 259 (82) | 53 (80) | 152 (85) | 54 (77) |

| ≥50 copies/mL | 55 (18) | 13 (20) | 26 (15) | 16 (23) |

| <1000 copies/mL | 293 (93) | 63 (95) | 171 (96) | 59 (84) |

| ≥1000 copies/mL | 21 (7) | 3 (5) | 7 (4) | 11 (16) |

- Note: Results are shown as n (%).

Agreement between adherence measures

The POC TFV LFA had moderate agreement with viral load ≥1000 copies/mL (kappa = 0.504, 95% CI 0.311–0.698) based on the Landis and Koch interpretation [11]. The Kappa for the POC TFV LFA was statistically significantly higher than the Kappa statistics for agreement between each self-reported adherence measure and viral load ≥1000 copies/mL (Table 3). There was limited precision when exploring the agreement between presence of TFV in urine and self-reported adherence by sex and pregnancy status (Supplementary Table 1). The Kappa statistics were largest among males compared to pregnant and non-pregnant females but all CIs overlapped.

| VL≥1000 | VL < 1000 | Kappa statistic (95% CI) | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POC TFV LFA | ||||

| TFV absent | 11 (52) | 9 (3) | 0.504 (0.311–0.698) | |

| TFV present | 10 (48) | 284 (97) | ||

| Missed doses in the past 3 days | ||||

| 1 or more doses missed | 5 (24) | 19 (6) | 0.163 (−0.007–0.332) | 0.015 |

| No doses missed | 16 (76) | 274 (94) | ||

| Missed doses in the past 7 days | ||||

| 1 or more doses missed | 5 (24) | 28 (10) | 0.113 (−0.034–0.259) | 0.003 |

| No doses missed | 16 (76) | 265 (90) | ||

| 2 or more doses missed | 3 (14) | 12 (4) | 0.118 (−0.053–0.288) | 0.003 |

| <2 doses missed | 18 (86) | 281 (96) |

- a p-value comparing each of the self-reported adherence Kappa statistics with the Kappa statistics for the POC TFV LFA using paired t tests for agreement coefficients, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Comparison of the POC urine TFV LFA and self-reported adherence to detect viraemia

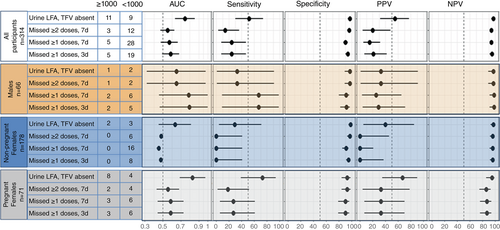

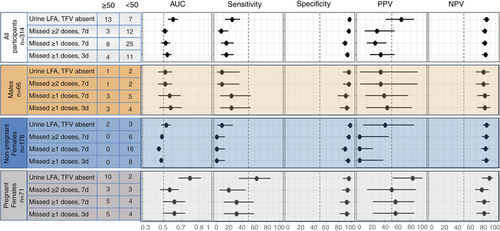

Figures 1 and 2 show the diagnostic characteristics of the POC TFV LFA and self-reported adherence measures to detect viral load ≥1000 and ≥ 50 copies/mL, respectively. Related data are presented in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Including all participants (n = 314), absence of TFV on POC TFV LFA was associated with viral load ≥1000 with a likelihood OR 34.7 (95% CI 12.0–101). The AUC for the POC TFV LFA (0.747 95% CI 0.637–0.856) was statistically significantly higher than for ≥1 and ≥2 missed ART doses in the past 7 days (AUC 0.571 95% CI 0.476–0.666 [p = 0.040] and AUC 0.551 95% CI 0.473–0.628 [p = 0.001], respectively. P-values adjusted for multiple comparisons). The difference between the AUC for the POC TFV LFA and ≥1 missed dose in the past 3 days (AUC 0.587 95% CI 0.492–0.681 [p = 0.071]) was not statistically significant. The point estimates for sensitivity and PPV were also higher for the POC TFV LFA but all 95% CIs were overlapping. Specificity and NPV were very high for the POC TFV LFA and all self-report measures.

When stratified by sex and pregnancy status, the likelihood OR for absence of TFV on the POC TFV LFA to detect viral ≥1000 copies/mL was 14.8 (95% CI 1.4–161) among males, 22.4 (95% CI 3.7–145) among non-pregnant females, and 36.7 (95% CI 7.3–184) among pregnant females. Among pregnant females who were the group with most non-adherence, the point estimates for the AUC, sensitivity and PPV were higher for the POC TFV LFA than for self-reported adherence, however all CIs were wide and overlapped (Figure 1). Similarly, the diagnostic characteristic CIs for the POC TFV LFA and the self-reported measures were wide and overlapped among non-pregnant females and among males.

Results using a viral load threshold of 50 copies/mL followed a similar pattern with tighter CIs due to the larger number of events and point estimates for AUCs, sensitivities and PPV were higher to detect viral load ≥1000 copies/mL (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 2) compared to viral load ≥50 copies/mL (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 3). In a supplementary analysis, results stratified by time since ART initiation (<2 years versus ≥2 years) followed a similar pattern to the main analysis with small differences in point estimates (Supplementary Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This cross-sectional evaluation found that the POC TFV LFA had better agreement with viral load than short-term missed dose recall and statistically significantly better ability to detect viraemia on two of three self-reported adherence measures assessed. Testing for TFV in urine using a POC TFV LFA could provide an alternative short-term adherence measure for PLHIV in routine care.

Very high specificities and NPVs show that presence of the TFV on the POC TFV LFA does very well to rule out patients who are not viremic. Our results are similar to findings of a recent study that found 12.5% specificity and 99% sensitivity of the POC TFV LFA to detect viral load ≥1000 copies/mL [13]. Used alone, the POC TFV LFA could provide a useful tool to rapidly assess short-term adherence and prompt adherence counselling and further intervention. A qualitive study among female PrEP users and providers in Kenya found that POC urine tests could be very feasible in routine care [14]. Use of the test has been piloted in a biofeedback intervention among pregnant women on PrEP in South Africa which increased PrEP adherence compared to routine counselling [15]. There is emerging evidence that patients and providers may find the POC TFV LFA a useful tool in clinical care for PLHIV, however there are limited published data in this area [13, 16, 17].

If the POC urine TFV LFA results could be reviewed together with real-time viral load test results this would provide a unique opportunity to flag patients for different interventions. Specifically, (1) patients who are viremic and have no TFV present require adherence support, (2) patients who are viremic but do have TFV present in their urine may be resistant or at risk of resistance, and (3) patients who are suppressed but have no TFV in their urine may have early or intermittent adherence difficulties. A small pilot study in South Africa among PLHIV at risk of treatment failure found that 14 of 16 patients with TFV present in urine and an elevated viral load (≥400 copies/mL) had resistance present and that urine screening may be useful to identify poor adherence and avoid resistance testing [18]. Data from Uganda and South Africa found that, among people with viral loads above 1000 copies/mL, 91% of those with TFV detected on the POC TFV LFA had drug resistance compared to 66% of those with no TFV detected [19]. Our study took place prior to the scale-up of DTG in South Africa which has implications for the development of resistance. A recent South African study found that the absence of TFV in urine was more strongly associated with viraemia among people receiving DTG, compared to efavirenz [20]. Recent evidence in the context of high genetic-barrier regimens (DTG-boosted or ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens) has shown that presence of TFV in urine could still be valuable to screen for potential resistance, despite the overall lower incidence of resistance [21]. In another study among patients considered at risk for viral failure using high genetic-barrier regimens, the POC TFV LFA was able to discriminate between those with and without viral failure with a high NPV (85%) and PPV (85%) [22].

Although power was limited in sub-group analyses, the difference between the performance of the POC TFV LFA and self-reported adherence appeared more pronounced in the sample of pregnant females in this study. Pregnant women showed higher levels of non-adherence compared to non-pregnant women and men which is consistent with the literature [23], and ART metabolism may differ during pregnancy [24, 25]. Research is needed to determine whether the threshold used in the POC TFV LFA of 1500 ng is the optimal threshold for TFV detection in urine during pregnancy. Historically, pregnant PLHIV were predominantly newly starting ART. However, following the success of ART scale-up under WHO Option B+ and Treat All, a large proportion of pregnancies are now among people already on ART as reflected by 70% of the pregnant group in this study with ≥2 years since ART initiation. In supplementary analyses, results did not differ substantially by duration on ART.

In non-pregnant females and males, diagnostic characteristics were similar for the POC TFV LFA to detect viral load ≥1000 and ≥ 50 copies/mL, but those of self-reported adherence measures varied. Further research with larger samples sizes and targeted recruitment of non-adherent individuals is needed to better understand these differences. It is possible that both adherence behaviour (adherence overall and behaviours such as ‘white coat adherence’ [26] or taking your treatment when you have a scheduled clinic visit) as well as the biases of self-reported adherence (such as social desirability and recall bias) differ among males and females, and among pregnant and non-pregnant females.

The results should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. In the recruited sample only a small number of participants had raised viral loads and non-adherence on the POC TFV LFA or on self-report. There was a very small number of individuals who reported missed doses which limited our ability to explore other self-reported adherence thresholds such as no doses taken in the past two or 3 days, which would have been a closer approximation to what is measured using the POC TFV LFA [8]. A large component of this sample was comprised of pregnant females, however, the accuracy of estimates of the POC TFV LFA in pregnancy is not well known. Understanding the performance of the POC TFV LFA in pregnancy is important as the use of the test in the context of ART and PrEP in pregnancy is increasing. The small sample of men reflects the ART services in this setting, where approximately 70% of all patients are female and recruitment of men living with HIV is challenging [27, 28]. The small sex and pregnancy subgroups in our study and limited variability in adherence limited our statistical power and the precision of our estimates. Laboratory tests were conducted in routine care and results abstracted from medical records resulting in missing data for some participants. Both self-reported adherence and the POC TFV LFA are short-term measures prone to social desirability bias. Self-reported adherence is known to be overestimated and the POC TFV LFA may be prone to white coat adherence where patients take doses of their medication before coming into the clinic to appear to adherent. It was beyond the scope of this study to measure TFV-DP in blood samples. However, this would have added considerable richness to the data. Larger studies with robust gold standard adherence measures will be useful to further examine the performance of this test in different populations, including in pregnant women. Despite these limitations, this work provides useful insights into the potential use of the POC TFV LFA in a routine care HIV treatment setting.

In summary, the POC TFV LFA is an easy-to-use, real-time, objective marker of short-term adherence with better agreement with and ability to detect viraemia than short-term missed ART dose recall. Further research is needed in larger samples, particularly in populations at risk of poor adherence and viral failure as well as among pregnant women, to better understand the application of this test in routine clinical care in general and for different populations of people on ART.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all study participants and to the staff at the Gugulethu Community Health Centre for their support. We thank our study field team for their work and Abbott for their donation of the urine lateral flow assays.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Tamsin Phillips was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number D43 TW009337 (Office of AIDS Research and the Fogarty International Center) and K43 TW011943 (the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health), and by the International AIDS Society through a CIPHER grant. Yolanda Gomba received scholarship support from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43 TW009774. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the NIH.