Diagnostic and treatment delays of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis before initiating treatment: a cross-sectional study

Abstract

enObjective

Shandong Province has implemented the standardised treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) supported by the Global Fund. The study aimed to understand the managements and delays of patients with MDR-TB before initiating their treatments.

Methods

All patients with MDR-TB who had completed intensive phase treatment from January 2010 to May 2012 were interviewed using a structured questionnaire. Delays and treatments were analysed. Diagnosis delay is defined as the period between having sputum smear results and drug susceptibility test (DST) results. Treatment delay was defined as starting MDR-TB treatment more than 2 days after receiving the diagnosis of MDR-TB. Total delay is the sum of diagnosis delay and treatment delay.

Results

In total, 110 patients with MDR-TB participated in the study. Median delay for diagnosis was 102 days. Over 80% of patients had a diagnosis delay longer than 90 days. MDR-TB treatments commenced after a median of 9 days after DST results, and over 37% of the patients with MDR-TB experienced treatment delays. Chronic cases or patients with indifferent attitude had significantly longer treatment delay than other groups (P = 0.03 and 0.03, respectively). During their delays, of 44 patients with retreatment failures, 12 (27.3%) were treated through adding single second line drugs (SLDs) to first-line regimens, and 25 (56.8%) were treated with first-line drugs. A high proportion of initial treatment failure/relapsed/returned cases (37%) and new cases (43%) were administered with SLDs.

Conclusions

Most of the patients with MDR-TB experienced prolonged diagnosis delay, which was the most important factor contributing to the total delay. Misuse of SLDs during the days was common, so necessary training should be given to prevent irrational prescription of medications.

Abstract

frObjectif

La province du Shandong a mis en place le traitement standardisé de la tuberculose multirésistante (TB-MDR), soutenu par le Fonds Mondial. L’étude visait à comprendre les prises en charge et les retards des patients atteints de TB-MDR avant l'initiation de leurs traitements.

Méthodes

Tous les patients TB-MDR qui avaient terminé le traitement de la phase intensive de janvier 2010 à mai 2012 ont été interrogés à l'aide d'un questionnaire structuré. Les retards et les traitements ont été analysés. Le retard de diagnostic a été défini comme la période comprise entre les résultats des frottis de crachats et ceux des tests de sensibilité aux médicaments (DST). Le retard de traitement a été défini comme le début du traitement de la TB-MDR plus de 2 jours après avoir reçu le diagnostic de TB-MDR. Le retard total étant la somme du retard de diagnostic et du retard de traitement.

Résultats

Au total, 110 patients TB-MDR ont participé à l’étude. Le délai médian pour le diagnostic était de 102 jours. Plus de 80% des patients avaient un retard de diagnostic de plus de 90 jours. Les traitements de TB-MDR ont débuté après une médiane de 9 jours après les résultats des DST et plus de 37% des patients TB-MDR ont subi des retards de traitement. Les cas chroniques ou les patients avec une attitude indifférente avaient significativement plus de retard de traitement que les autres groupes (P = 0,03 et 0,03, respectivement). Au cours de leurs retards, sur 44 patients avec un échec de retraitement, 12 (27,3%) ont été traités par l'ajout d'un seul médicament de 2nde ligne à des schémas de 1è ligne et 25 (56,8%) ont été traités avec des médicaments de 1è ligne. Une proportion élevée des échecs de traitement initiaux/rechutes/retours (37%) et de nouveaux cas (43%) ont été administrés avec des médicaments de 2nde ligne.

Conclusions

La plupart des patients TB-MDR ont connu un retard de diagnostic prolongé, ce qui était le facteur le plus important contribuant au retard total. La mauvaise utilisation des médicaments de 2nde ligne pendant les retards était courante. Il est donc nécessaire qu'une formation soit donnée pour éviter la prescription irrationnelle des médicaments.

Abstract

esObjetivo

La provincia de Shandong ha implementado el tratamiento estandarizado para la tuberculosis multirresistente (TB-MR) con el apoyo del Fondo Mundial. El objetivo del estudio era comprender el manejo y los retrasos de pacientes con TB-MR antes de comenzar el tratamiento.

Métodos

Se entrevistó a todos los pacientes con TB-MR que habían completado la fase intensiva del tratamiento entre Enero 2010 y Mayo 2012 utilizando un cuestionario estructurado. Se analizaron los retrasos y tratamientos. Los retrasos en el diagnóstico se definieron como el periodo entre tener los resultados de la baciloscopia de esputo y los de susceptibilidad a medicamentos (SM). El retraso en el tratamiento se definió como comenzar el tratamiento de TB-MR más de 2 días después de recibir el diagnóstico de TB-MR. El retraso total es la suma del retraso en el diagnóstico y el retraso en el tratamiento.

Resultados

En total, 110 pacientes con TB-MR participaron en el estudio. El retraso medio para el diagnóstico era de 102 días. Cerca del 80% de los pacientes tenían un retraso en el diagnóstico de más de 90 días. Los tratamientos para TB-MR comenzaban después de una media de 9 días después de tener los resultados de SM, y cerca del 37% de los pacientes con TB-MR experimentaban retrasos en el tratamiento. Los casos crónicos o pacientes con una actitud indiferente tenían retrasos de tratamiento significativamente más largos que otros grupos (P = 0.03, and 0.03, respectivamente). Durante sus retrasos, de 44 pacientes con recaídas en fallo terapéutico, 12 (27.3%) fueron tratados añadiéndose un solo medicamento de segunda línea a los regímenes de primera línea y 25 (56.8%) fueron tratados con su medicamento de primera línea. A una alta proporción de los fallos de tratamiento iniciales / recaídas / casos devueltos (37%) y nuevos casos (43%) se les administraron medicamentos de segunda línea.

Conclusiones

La mayoría de los pacientes con TB-MR experimentaron un retraso prolongado en el diagnóstico, lo cual era el factor más importante en el retraso total. El mal uso de medicamentos de segunda línea era común, por lo cual el entrenamiento es necesario para prevenir la prescripción irracional de medicaciones.

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is defined as tuberculosis strains resistant to at least isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RFP). MDR-TB poses a paramount threat to global TB control and incurs a huge burden to international community due to its difficult, expensive, less effective and toxic treatment. To diagnose MDR-TB, drug susceptibility tests (DSTs) need to be undertaken. World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that DST is routinely provided to all patients with TB or patients with high risk of drug resistance at the start of treatment 1. In 2008, DST was performed in only 3% of previously treated cases in 27 countries with the highest burden of MDR-TB 2. Solid culture and conventional DST take between 2 and 4 months or longer in most countries 3-5. Delay of appropriate treatment contributes to the poor treatment outcome, further transmission and amplification of MDR-TB, while delayed treatment or inadequate treatment with a single second-line drug (SLD) also increase the risk of generating extensive drug resistance (XDR) 3, 6.

China carries the largest burden of MDR-TB and has the second highest number of TB cases in the world 7. According to the national 2007 TB drug resistance survey in China, 5.7% of new smear-positive cases and 25.6% of retreated cases were MDR-TB 8, and about 120 000 new MDR-TB cases are estimated in China annually 8. To improve MDR-TB control, a project supported by the Global Fund (GF) against HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria has been implemented in several provinces of China, including Shandong Province, since 2010.

Shandong Province, located in eastern China with a population of 94 million, is divided into 17 prefectures and 140 counties. By 2005, directly observed treatment, short-course (DOTS) strategy had covered all counties and the detection rate of new smear-positive case has been more than 70% in Shandong Province. A basic DOTS unit, called TB dispensary, is located at the county level, providing free anti-TB treatment according to DOTS strategy 9.

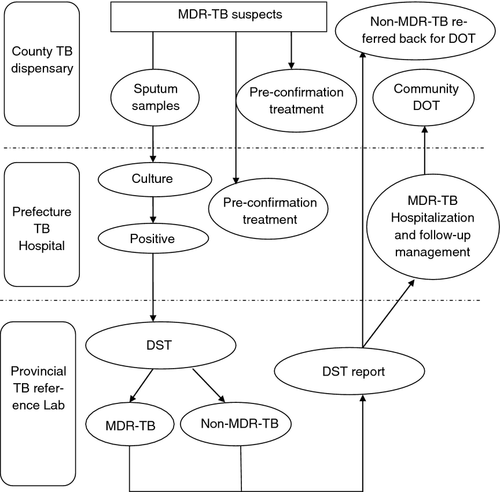

Five prefectures have been implementing the GF project since 2010, which covers 44 counties with a total population of 33 million. TB dispensaries at the county level are responsible for collecting and delivering sputum samples of MDR-TB suspects to the laboratories of prefectural designated MDR-TB hospitals (DMH) for culture, which include chronic patients who experienced multiple treatment courses but remained smear positive, the relapsed/returned patients, patients with initial treatment and retreatment failure, close contacts of MDR-TB cases and non-converted new cases by the end of the intensive treatment phase. DSTs are only available in the provincial reference laboratory, which are performed using conventional proportion method on solid media as recommended by the WHO 10. DST results are sent back to DMH, and the project officer immediately informs patients with MDR-TB, via community health centres if necessary, and requests the patient for a clinical evaluation. DMH serves as the prefectural MDR-TB clinical management centre. The standard regimen of GF project is 6 months of intensive phase using amikacin, moxifloxacin, pyrazinamide, cycloserine (para-aminosalicylic acid) and protionamide and 18 months of continuous phase using moxifloxacin, pyrazinamide, cycloserine (para-aminosalicylic acid) and protionamide. Although WHO recommends GeneXpert method for its potential to decrease diagnosis delays 3, expanding GeneXpert at the facility level requires tremendous financial resources and capacity building that the middle- and low-income countries cannot afford to. Those who could not tolerate the standardised treatment regimens or needed individualised regimens were not recruited in the project. The procedures of diagnosis are illustrated in Figure 1.

Regarding regimens given to patients during the diagnosis of MDR-TB, the China's MDR-TB management guideline suggests providing first-line anti-TB regimens to patients who are initial treatment failure/relapse/return cases and new cases, while empirical second-line anti-TB regimens should be given to those who are chronic/retreatment failures after clinical evaluation 11.

The management of MDR-TB has been extensively documented; however, little has been reported regarding management issues during the time from being suspected as MDR-TB to initiation of MDR-TB treatment. The study aimed to fill this gap and to provide recommendations for the future scale-up of programmatic management of MDR-TB.

Methods

We selected all patients with MDR-TB who were registered from 2010 and had completed more than 6 months of intensive treatment in May 2012. Medical records of all these patients regarding their treatment during the MDR-TB diagnostic period were collected and reviewed. Face-to-face interviews were conducted for all these patients using a structured questionnaire about their knowledge and perceptions regarding TB, care-seeking process and treatments before they were formally enrolled into MDR-TB treatment. In this study, the definitions of patient categories are in line with WHO guideline for treatment of tuberculosis 2. Diagnosis delay was defined as the period between the time when sputum smear results were available and the time when DST results were available. Treatment delay was defined as starting MDR-TB treatment more than 2 days after receiving the diagnosis of MDR-TB.

Differences in proportions were tested using Pearson's chi-square test. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using the exact binomial method. All tests were two-sided, and a threshold of P = 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. Factors associated with treatment delay including age, sex, education, treatment category and patients' perceptions were tested.

Ethical clearance for this study was sought from the Ethics Committees of the Shandong Provincial Chest Hospital, China. Written informed consents were obtained from participants when they agreed to attend this study.

Results

In the five prefectures, 119 cases had finished 6 months of treatment, of whom, 110 (92.4%) were interviewed. Nine patients who were too weak, not available at the time, or already defaulted from the treatment did not participate in the interview. Among 110 patients, 81 (73.6%) were males and 29 (26.4%) were females. Most of whom had not attended high school education. Farmers accounted for 50%. Among 110 patients, 21 (18%) were new cases, and 89 (80.9%) were retreated cases. Of whom, 44 (49.4%) were retreatment failure.

Diagnosis delay

Most of the cases (81%) had a diagnosis time longer than 90 days, and 19% of the cases had a diagnosis time longer than 180 days. The median diagnosis delay was 102 days. The median interval between the time when sputum was sent for culture and the time when culture result was available was 44.5 days, while the median interval was of 66 days between the time when strains were sent for DST and the time when DST results were received (Table 1).

| Time interval (day) | Mean | Median | 25th percentile | 75th percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of diagnosis delay | 110 | 102 | 88 | 118 |

| Time between sputum result available and sputum sample sent for culture | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Time between sputum sample received for culture and culture result available | 47.3 | 44.5 | 31 | 61 |

| Time between culture result available and samples sent for DST | 5.2 | 0 | 0 | 3.5 |

| Time between samples sent for DST and DST result received | 68.1 | 66 | 33 | 87.5 |

| Days of treatment delay | 25.3 | 9 | 0 | 25 |

| Total delay | 140.5 | 120 | 93 | 161 |

Treatment delay and risk factors

Over 37% of the 110 cases had treatment delay, with a median interval of 9 days. The median total delay, that is the diagnostic delay plus treatment delay, was 120 days (Table 1). Sex, age, education, profession and previous treatment expenditures were not significantly associated with treatment delay. However, chronic cases who had experienced multiple treatment courses were more likely to have treatment delay (P = 0.033), and patients who did not appreciate the seriousness of TB tended to have treatment delay (P = 0.028; Table 2).

| Factors | No. | ≤2 days | >2 days | P | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | |||||

| Category | ||||||

| New cases | 21 | 12 (57.1) | 9 (42.9) | 0.053 | 0.107 | (0.011, 1.033) |

| Relapsed | 24 | 17 (70.8) | 7 (29.2) | 0.015 | 0.059 | (0.006, 0.571) |

| Initial treatment failure | 13 | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | 0.012 | 0.043 | (0.004, 0.502) |

| Retreatment failure | 44 | 29 (65.9) | 15 (34.1) | 0.020 | 0.074 | (0.008, 0.658) |

| Chronicle cases | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | 1 | ||

| Perceptions to TB | ||||||

| TB is a serious disease | 97 | 64 (65.9) | 33 (34.1) | 0.028 | 0.258 | (0.072, 0.920) |

| TB is not a serious disease | 12 | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | 1 | ||

Use of second-line TB drugs

While waiting for DST results, patients were treated at the specialised TB hospitals, county TB dispensaries and private health facilities. Patients' categories, treatment principle for each category, the number and percentage of patients using SLDs, and facilities using SLDs to treat patients while waiting for DST results are illustrated in Table 3. Of 44 patients with retreatment failures, 12 (27.3%) were treated through adding single SLDs to first-line regimens, and 25 (56.8%) were treated with first-line drugs. A total of 36.8% of initial treatment failure/relapse/return cases (14/38) and 42.9% of new cases (9/21) were administered with SLDs. The most frequently used SLDs were fluoroquinolones (80%) including ofloxacin or levofloxacin, which was followed by injectable aminoglycoside (20%), mainly amikacin. Misuse of SLDs mostly happened in the specialised TB hospitals.

| Category of patients | Principle of treatment before confirming MDR-TB | No. of cases | Cases used second-line anti-TB drugs (%) | Different health facilities administered second-line anti-TB drugs (No. of case and proportion) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Added single drugs | Added multiple drugs | Specialised TB hospital | County TB dispensary | Private facilities | |||

| Retreatment failure/chronic cases | Existing treatment or empirical MDR-TB treatment | 44 | 19 | 12 (27.3) | 7 (15.9) | 15 (78.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| Initial treatment failure/relapsed/return | Retreatment | 38 | 14 | 10 (26.3) | 4 (10.5) | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | 0 |

| New cases | Initial treatment | 21 | 9 | 8 (38.1) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (33.3) | 0 |

| Others | Empirical treatment | 7 | 2 | 2 (28.6) | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 110 | 44 | 32 (29) | 12 (10.9) | 35 (79.5) | 8 (18.2) | 1 (2.3) | |

Discussion

WHO recommends that one laboratory for sputum culture and DST should be established in every five million population 12. However, the capacity of laboratory to detect anti-TB drug resistance is still low in China. In this study, an area covering 33 million in Shandong did not have the DST capacity but had to rely on the provincial reference laboratory, which may have contributed to the severe diagnosis and treatment delays of patients with TB.

According to China's MDR-TB management guideline, results of conventional DST should be read within 4 weeks of inoculation 11. In our study, it took 66 days in median to wait for results after receiving samples for DST. The total delay was 4 months in our study, which was worse than findings of two studies in South Africa. Where a mean delay of 12.4 weeks from the date of sputum collection for culture and DST to the start of treatment 13, and an average of 5–6 weeks' delay using traditional culture methods were reported 14. The longer delay in Shandong Province was mostly due to the limited capacity of laboratories at the prefectural level, because samples had to be sent to the provincial laboratory for DST and where the amount of samples often exceeded its handling capacity. Process of sample delivering and feedback of DST results could have taken less time if county-level TB dispensary, prefecture-level DMH and provincial reference laboratory had better coordination in place. However, more importantly, DMH laboratories should be responsible for DST of their respective prefectures at the earliest occasion and be equipped with necessary devices, trained technicians and infection control facilities, which will significantly reduce the DST time.

Application of rapid DST techniques, including providing finances and reagent supplies, may be useful to reduce diagnostic delays and expedite treatment for drug-resistant TB, but the methods should be piloted before wide application 15. GeneXpert MTB/RIF, line probe assays and Genechip are being evaluated by China's National Reference Laboratory, but are yet to be incorporated into the current diagnostic algorithms. Besides the evaluation of these methods, the high initial costs and the recurrent costs for most rapid tests, and related capacity building and facility costs should also be addressed before scale-up 16. Bactec-MGIT 960 is being used in some hospitals. However, due to its high cost of equipment and reagents, over 10 days of turnaround time and promise of GeneXpert MTB/RIF, many TB hospitals in China hesitate to introduce the technology.

We observed a profoundly long delay in initiating anti-MDR-TB treatment, which may increase the possibility of transmitting the disease to the general population 17. Unlike Chen's study on drug-susceptible TB, this study showed that financial burden did not prevent patients with MDR-TB from seeking MDR-TB treatment probably because the GF project provided a comprehensive free treatment and care package 18. Chronic cases and those who did not regard TB as a serious disease were more likely to have treatment delay.

Irrational regimens, substandard drugs, insufficient dosage and inadequate treatment period and inappropriate drug administration have contributed to the development of drug resistance 19. China's guidelines require that empirical MDR regimen be given to patients of retreatment failures before drug resistance profile is confirmed to reduce treatment delay 11. Empirical MDR-TB treatment consists of at least four drugs with the certain effects based on their treatment histories 2. Clearly, this study revealed that the guidelines were not properly followed; for example, some retreatment failure cases were not put on empirical MDR-TB treatment, but were treated by adding single drugs to first-line anti-TB regimens. Furthermore, more than 39% of the patients with MDR-TB, who were initial treatment failure/relapse/return cases or new cases, were treated with second-line anti-TB drugs, which is against the national guidelines. Another striking fact was the inadequately formulated regimens mainly occurred at specialised TB hospitals. One possible reason for misusing SLDs may be that health facilities induce demand on irrational use of SLDs to generate revenues from treating patients 20. Previous studies also established that specialist hospitals had mismanaged drug-susceptible TB cases compared with TB dispensaries 21, 22.

The addition of one single second-line drug would increase the risk of generating XDR-TB. A study by 23 showed that there is poor administration of drugs in health facilities in China, where some second-line drugs, such as fluoroquinolone, are easily and extensively prescribed for respiratory infections and other bacterial infections and in some cases even available without a prescription in local drug stores. In addition, easy access and inappropriate use of these drugs increase the risk for the emergence of drug resistance 24.

Worth to mention is that some of Chinese guidelines' recommendations are questionable and may need further emendation in the future. For example, giving retreatment regimen to an initial treatment failure without obtaining DST results is debatable. As WHO recommends that DST should be given to all previously treated patients with TB at or before the start of treatment, patients whose prior course of therapy has failed should therefore receive an empirical MDR regimen 2. However, DST is not yet routinely available in Shandong and most of China. WHO recommends using the empirical regimens should continue throughout the course of treatment. Unreasonable treatment regimens is one of the important reasons that produces MDR-TB 25.

The study was a retrospective investigation, and patients may not recall all the details correctly. As part of large study examining treatment issues before MDR-TB diagnosis and after diagnosis 26, only patients who had competed 6 months of intensive treatment in the GF project were included, so selection bias exists in the study. Patients who were not included in the GF project did not receive the financial support and may experience more severe delays; thus, the study may have underestimated patient delays in normal conditions. Shandong is a province with very low prevalence of HIV/AIDS, so we did not include information about these patients' HIV status.

Conclusion

We found that most patients experienced prolonged diagnosis delay in MDR-TB treatment. Rapid DST techniques should be introduced at the prefectural MDR-TB centres. Sample transportation and information exchange need to be further streamlined. Patients who had chronic TB or did not appreciate the seriousness of TB treatment tended to have treatment delay. Misuse of SLDs was common, and so necessary training should be introduced to prevent irrational prescription of medications.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded and proved by COMDIS Health Service Delivery Research Programme Consortium (COMDIS HSD), a six-year programme (2011–16) funded by the UK Department for International Development. COMDIS HSD did not play a role in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We also thank Robinah Najjemba of Department of Essential of Medicine, World Health Organization who proofread the manuscript.