Road traffic injuries in northern Laos: trends and risk factors of an underreported public health problem

Abstract

enObjectives

Road traffic injuries (RTI) have become a leading cause for admissions at Luang Namtha Provincial Hospital (LNPH) in rapidly developing northern Laos. Objectives were to investigate trends, risk factors and better estimates of RTI.

Methods

Repeated annual surveys were conducted with structured questionnaires among all RTI patients at LNPH from 2007 to 2011. Hospital and police data were combined by capture–recapture method.

Results

The majority of 1074 patients were young [median 22 years (1–88)], male (68%), motorcyclists (76%), drove without licence (85%) and without insurance (95%). Most accidents occurred during evenings and Lao New Year. Serious motorbike injuries were associated with young age (1–15 years), male sex (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.1–4.6) and drivers (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.3); more serious head injuries with alcohol consumption (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.7–3.7), male sex (OR 2.3, 95% CI 1.4–3.7) and no helmet use (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.4). No helmet use was associated with young age, time period, pillion passengers (OR 2.7, 95% CI 1.6–4.7), alcohol (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–2.8) and no driver license (OR 2.0; 95% CI 1.1–3.4). Main reasons not to wear helmets were not possessing one, and being pillion passenger. Capture–recapture analysis showed four times higher RTI estimates than officially reported. Mortality rate was 11.6/100.000 population (95% CI 5.1–18.1/100.000).

Conclusions

RTI were substantially underestimated. Combining hospital with police data can provide better estimates in resource-limited settings. Preventive programmes and law enforcement have to target male drivers, alcohol, licensing and helmet use, especially among children and pillion passengers. Increased efforts are needed during evening time and special festivals.

Abstract

frObjectifs

Les blessures des accidents de la route (BAR) sont devenues une cause majeure des admissions à l'Hôpital Provincial de Luang Namtha (LNPH) dans le nord du Laos, une région en rapide développement. Les objectifs étaient d’étudier les tendances, les facteurs de risque et obtenir de meilleures estimations des BAR.

Méthodes

Des surveillances annuelles répétées ont été réalisées grâce à des questionnaires structurés chez tous les patients avec des BAR à LNPH de 2007 à 2011. Les données hospitalières et de la police ont été combinées par la méthode de capture-recapture.

Résultats

La majorité des 1074 patients étaient des jeunes [médiane de 22 ans (1 à 88)], de sexe masculin (68%), des motocyclistes (76%), conduisant sans permis (85%) et sans assurance (95%). La plupart des accidents se sont produits dans la soirée et au Nouvel An Lao. Les blessures de motos graves ont été associées au jeune âge (1 à 15 ans), au sexe masculin (OR = 2,2; IC95%: 1,1 à 4,6) et aux conducteurs (OR = 2,1; IC95%: 1,1 à 4,3); les blessures à la tête plus graves, étaient associées à la consommation d'alcool (OR = 2,5; IC95%: 1,7 à 3,7), au sexe masculin (OR = 2,3; IC95%: 1,4 à 3,7) et à la non utilisation du casque (OR = 2,0; IC95%: 1,2 à 3,4). L'absence de port du casque a été associée au jeune âge, à la période de temps, aux passagers du siège arrière (OR = 2,7; IC95%: 1,6 à 4,7), à l'alcool (OR = 1,9; IC95%: 1,2 à 2,8) et à l'absence de permis de conduire (OR = 2,0; IC95%: 01,01 à 03,04). Les principales raisons de l'absence de port du casque étaient le fait de ne pas en posséder et d’être passager. L'analyse de capture-recapture a révélé des estimations de BAR 4 fois plus élevées qu'officiellement rapportées. Le taux de mortalité était de 11,6 / 100.000 habitants (IC95%: 5,1 à 18,1/100.000).

Conclusions

Les BAR sont largement sous-estimées. La combinaison des données de l'hôpital à celles de la police peut fournir de meilleures estimations dans les zones à ressources limitées. Les programmes de prévention et l'application de la loi devraient cibler les conducteurs de sexe masculin, l'alcool, les permis et le port du casque, en particulier pour les enfants et les passagers du siège arrière. Des efforts accrus sont nécessaires durant la soirée et au cours des festivals spéciaux.

Abstract

esObjetivos

Las heridas por accidentes de tráfico (HAT) se han convertido en una de las principales causas de admisión hospitalaria en el Hospital Provincial de Luang Namtha (HPLN) en una zona en rápido desarrollo del Norte de Laos. Los objetivos del estudio eran investigar las tendencias, factores de riesgo y realizar una mejor estimación de las HAT.

Métodos

Se realizaron estudios anuales repetidos mediante cuestionarios estructurados entre todos los pacientes con HAT en el HPLN entre 2007-2011. Se combinaron datos hospitalarios y policiales mediante el método captura-recaptura.

Resultados

La mayoría de los 1074 pacientes eran jóvenes [mediana 22 años (1-88)], hombres (68%), motociclistas (76%), conduciendo sin licencia (85%) y sin seguro (95%). La mayoría de los accidentes ocurrían durante las noches y en el Año Nuevo de Laos. Las heridas de moto más graves estaban asociadas con ser más jóvenes (1-15 años), ser del sexo masculino (OR 2.2, IC 95% 1.1-4.6), y ser el conductor (OR 2.1, IC 95% 1.1-4.3). Las heridas de la cabeza más graves estaban asociadas con el consumo de alcohol (OR 2.5, IC 95%CI 1.7-3.7), ser del sexo masculino (OR 2.3, IC 95% 1.4-3.7) y no utilizar casco (OR 2.0, IC 95% 1.2-3.4). El no utilizar casco estaba asociado con ser más joven, el periodo de tiempo, ser pasajero (OR 2.7, IC95% 1.6-4.7), consumo de alcohol (OR 1.9, IC 95% 1.2-2.8), y no tener licencia para conducir (OR 2.0; IC95% 1.1-3.4). Las principales razones para no llevar casco eran no tener uno, y ser el pasajero. El análisis de captura-recaptura mostró unos cálculos de HAT 4 veces mayores que lo reportado oficialmente. La tasa de mortalidad era de 11.6/100.000 habitantes (IC 95% 5.1-18.1/100.000).

Conclusiones

Los HAT estaban sustancialmente infravalorados. La combinación de datos hospitalarios y de la policía podría proveer cálculos más precisos en lugares con recursos limitados. Los programas preventivos y de cumplimiento de la ley deberían prestar especial atención al conductor masculino, al consumo de alcohol del conductor, al que tenga licencia y al uso del casco - en especial de los niños y pasajeros. Es necesario incrementar esfuerzos durante las noches y en fiestas especiales.

Introduction

Road traffic injures (RTI) are the 8th most common cause of death globally 1. Low- and middle-income countries carry a disproportionate high burden with 91% of the world's fatalities 2. In the western Pacific region, RTI have become the leading cause of death among 15- to 44-year-olds 3.

In Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos), RTI have dramatically increased with the recent economic development from a low- to a lower middle-income country 4, 5. The majority of its 6.8 million people live in rural areas with underdeveloped infrastructure 4, 5. An annual peak of RTI is seen in April during Lao New Year associated with excessive alcohol consumption 6. With new trans-Asian highway construction, RTI have become the leading cause for hospital admissions in Luang Namtha Province (LNP), northern Laos, in 2006 7. Road safety campaigns in 2007 could temporarily reduce severe RTI by 35% and increase helmet use from 11% to 46%, but no further thereafter 7.

Knowledge of the local situation and common risk factors is essential for effective road safety programmes. Most RTI go unrecorded, and official statistics only reflect part of the problem 8, 9. Some data are already available from the country's capital Vientiane 8-13 but data from rural areas remain scarce. Data validity could be improved if several sources were combined using the capture–recapture method as in other resource-limited settings without reliable surveillance systems 14-18. This method is commonly used to calculate hidden animal populations; a sample is captured, marked and released. In a later sample, the number of marked (‘recaptured’) individuals should be proportional to the marked individuals in the whole population.

The study was conducted to identify characteristics, trends and risk factors associated with RTI in LNP from 2007 to 2010, and to investigate reasons for not wearing helmets. Official police and hospital data were combined to estimate the real RTI incidence.

Methods

Study site

LNPH is a 50-bed hospital which serves the population (149 000 people in 2007) as the referral centre for five district hospitals and the military hospital of the province (Figure 1). It is the only hospital offering X-ray, bone surgery and intensive care for trauma patients 7. CT scan is not available. Seriously injured patients, especially with head trauma, need to be transferred by plane to the capital Vientiane. Around 20 000 outpatients and 3300 inpatients are treated per year 19.

Study procedure

First, a baseline survey of all RTI was conducted from December 2007 to December 2008. Second, the survey was repeated until 2011 each year from December to January as the two months with previously average RTI numbers. Third, an additional semi-quantitative survey was conducted to identify reasons and characteristics for not wearing helmets. A different time period (March–October 2009) was purposively chosen including months with maximum variation of RTI numbers.

All patients were eligible if presenting with injuries from road traffic accidents. Patients were included if informed consent was given. In case of inability to understand or answer the questionnaire, next of kin were interviewed if consenting. In case of death on the road/during transportation, information was collected from witnesses and accompanying persons. The additional helmet survey was performed only among motorcyclists over 12 years of age who were able to answer and consented.

A structured questionnaire was adapted from surveys by Handicap International in Vientiane 9-11. Questions included characteristics of patients (age, sex, district, occupation, alcohol and drug consumption, insurance, driving license), patient transfer to the hospital, type of road user (RU), time and mode of accident, characteristics of accident (vehicle, vehicle's light, road and weather condition, helmet use, police investigation) and injury characteristics. A simplified pretested anonymous questionnaire was used for the helmet survey. It included accident characteristics, patient's characteristics (age, occupation, alcohol consumption) and helmet use. Main outcome was investigated by the open question: ‘Why did you not wear a helmet?’

Interviews were performed by trained nurses at the emergency department and ICU in the patient's room to ensure confidentiality. Most answers were to be ticked, including injury site and severity on a simplified body pictogram.

Four categories of severity of injury were defined. (i) superficial injury (minor wound(s)/skin abrasion); (ii) moderate injury (wound that needed suturing/minor surgery, e.g. lacerations); (iii) severe injury (fracture, injury that needed major surgery, e.g. splenectomy, or ICU treatment, e.g. chest drain for hematopneumothorax, intracerebral bleeding); and (iv) death. Vulnerable road users (VRU) included pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists 2. Young age describes age 0–15 years.

Data processing and analysis

Data were entered and analysed with EpiInfo (Version 3.5.1, CDC, USA). All data entry was cross-checked by two persons against original data sheets. The numbers of RTI and deaths in 2008 in LNP were collected from the records of the LNP traffic police in 2009. Age was stratified in nine groups with equal numbers to check for potential interaction.

The following outcome variables were investigated by univariate and multivariate analysis: (i) serious injuries in motorbike riders (categories 3 and 4); (ii) more serious head injuries in motorbike riders, defined as the above categories plus category 2 (moderate injury); (iii) no helmet use at time of accident.

Variables investigated were age group, male gender, being the driver, driver license, no helmet used, alcohol consumption, poor weather condition (any other condition than good weather), time of the day (grouped in 4 hourly steps) and study time periods. For helmet use, two more variables were included: residency in district Namtha and occupation, and position on the motorbike (driver or pillion).

Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and Student's t-test/anova for normally distributed continuous data. We used stepwise down multivariate logistic regression models to control for confounding and interaction. All variables with P < 0.02 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis, plus always the variables age group and gender. We considered a two-sided P < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Capture–recapture analysis

We estimated the real number of RTI in LNP (‘N’) over one year (2008) using a capture–recapture analysis 14. Traditionally, the marking of ‘recaptured’ individuals (‘m’) is done by matching of individuals listed in both samples: in the police records of all RTI (‘M’) and in the hospital list of all RTI patients (‘n’). In analogy to verbal autopsy as a substitute for real autopsy, we used the survey's question whether police investigated the accident as the marking of ‘recaptured’ individuals (‘m’). Calculation was performed with the following formula: m/M = n/N.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Lao National Ethics Committee for Health Research, Vientiane. Informed verbal consent was obtained from all participants or close relatives in case of patient's inability.

Results

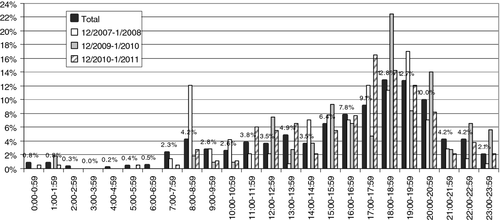

A total of 1080 patients were recruited. Six patients were excluded due to insufficient data. Of the final 1074 patients, 784 (73.0%) were included in the baseline survey, 107 (10.0%), and 183 (17.0%) in the yearly repeated surveys. The majority were young men and VRU (Table 1). Most RTI happened from falls (43.1%) and collisions with vehicles (42.3%). Frequent accident time was in the evening (Figure 2), during weekends (32.7% of 1068) and the month of the Lao New Year celebrations (15.9% of 718 in 2008). Most accidents happened on straight (62.0%), paved (87.7%) and dry roads (92.3%), 50.3% during good weather conditions. A minority of vehicle riders had switched on the lights (28.4% of 1007; 38.4% lights off, 33.2% unknown). Only two farm tractor riders had used lights (31 lights off, 32 unknown).

| Time period | Total (17 months) (%) | December 2007–January 2008 (2 months) (%) | December 2009–January 2010 (2 months) (%) | December 2010–January 2011 (2 months) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 1074 | 141 | 107 | 183 |

| Median age (rangea) | 22 (1–88) | 22 (2–59) | 23.5 (3–67) | 22 (3–75) |

| Male | 734 (68.4) | 94 (66.7) | 72 (67.3) | 122 (66.7) |

| Main occupation | ||||

| Student/pupil | 380 (35.4) | 53 (37.6) | 33 (30.8) | 73 (39.9) |

| Farmer | 300 (28.0) | 40 (28.4) | 28 (26.2) | 46 (25.1) |

| Government employee | 136 (12.7) | 12 (8.5) | 18 (16.8) | 20 (10.9) |

| Worker | 123 (11.5) | 11 (7.8) | 15 (14.0) | 22 (12.0) |

| Vendor | 44 (4.1) | 6 (4.3) | 3 (2.8) | 6 (3.3) |

| Police | 21 (2.0) | 4 (2.8) | 1 (0.9) | 5 (2.7) |

| Soldier | 18 (1.7) | 3 (2.1) | 3 (2.8) | 3 (1.6) |

| Driver | 8 (0.7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 28 (2.6) | 4 (2.8) | 6 (5.6) | 4 (2.2) |

| None/unknown | 15 (1.4) | 8 (5.7) | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| Referred from | ||||

| Accident site | 903 (84.2) | 117 (83.0) | 89 (84.0) | 137 (74.9) |

| Other hospital | 105 (9.8) | 20 (14.2) | 10 (9.4) | 21 (11.5) |

| Home | 63 (5.9) | 2 (2.1) | 7 (6.6) | 25 (13.7) |

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Type of RU/vehicle | ||||

| Pedestrian | 66 (6.1) | 5 (3.5) | 6 (5.6) | 13 (7.1) |

| Bicycle | 43 (4.0) | 6 (4.3) | 1 (0.9) | 9 (4.9) |

| Motorbike | 818 (76.2) | 95 (67.4) | 87 (81.3) | 140 (76.5) |

| Tractor | 65 (6.1) | 24 (17.0) | 12 (11.2) | 10 (5.5) |

| Pickup/car | 23 (2.1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 5 (2.7) |

| (Mini)Van | 28 (2.6) | 9 (6.4) | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| Bus | 20 (1.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Truck | 10 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 4 (2.2) |

| Injury severity | ||||

| No visible injury | 97 (9.1) | 2 (1.4) | 12 (11.3) | 11 (6.0) |

| Superficial | 560 (52.5) | 74 (53.2) | 47 (44.3) | 118 (64.5) |

| Moderate | 308 (28.9) | 50 (36.0) | 32 (30.2) | 41 (22.4) |

| Severe | 85 (8.0) | 11 (7.9) | 11 (10.4) | 9 (4.9) |

| Death | 17 (1.6) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (3.8) | 4 (2.2) |

- a Two-thirds (66.6%) of patients were between 15 and 34 years of age.

Drivers' characteristics

The majority of drivers was male (81.4% of 653) and had no driver's license (85.5% of 585) nor vehicle insurance (94.9% of 622), and almost half had drunken alcohol (47.4% of 648), without any obvious trend over the years. Alcohol use was most common among male drivers (52.2% vs. 26.4% female, OR 3.04, 95% CI 1.37–2.64). Drug use was reported by five male drivers (0.8% of 650, 98 unknown).

Injury patterns

Most RTI were not severe (Table 1). Affected body parts were mainly extremities (62.6%, head: 40.9%, trunk 19.4%). Most deaths were males (14/17), motorcyclists (12/17) and farm tractor riders (4/17), and occurred from head injuries (12/17). Fatalities were older than survivors (28 years, range 6–67, vs. 22 years, 1–88, respectively; P = 0.02). Farm tractor riders had the highest rates of serious injuries (17/65 vs. 85/1009 of all other RU, OR 3.85, 95% CI 2.12–6.99).

Injuries and helmets in motorcyclists

Serious RTI in motorcyclists were significantly associated with being the driver, male and young (Table 2). More serious head injuries happened in 19.8% of motorcyclists. They were associated in multivariate analysis with alcohol consumption (OR 2.49, 95% CI 1.70–3.65), male sex (OR 2.25, 95% CI 1.38–3.66) and no helmet use (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.16–3.41). Not wearing a helmet was associated with young age, time period of survey, pillion riding, alcohol consumption and lack of driver license (Table 3).

| Serious (%) | Not serious (%) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Number | 69 (8.4) | 749 (91.6) | ||||

| Median age (range) | 25 (4–60) | 22 (1–80) | 0.11 | |||

| Age groupa | ||||||

| 1–15 years | 11 (16.2) | 81 (10.8) | 0.36 | 1 | ||

| 16–17 years | 3 (4.4) | 80 (10.7) | 0.20 (0.05–0.75) | 0.017 | ||

| 18–19 years | 8 (11.8) | 103 (13.8) | 0.41 (0.15–1.11) | 0.079 | ||

| 20–21 years | 4 (5.9) | 71 (9.5) | 0.26 (0.08–0.89) | 0.032 | ||

| 22–23 years | 5 (7.4) | 84 (11.2) | 0.30 (0.10–0.92) | 0.035 | ||

| 24–27 years | 9 (13.2) | 86 (11.5) | 0.53 (0.20–1.40) | 0.202 | ||

| 28–33 years | 8 (11.8) | 86 (11.5) | 0.46 (0.17–1.25) | 0.128 | ||

| 34–42 years | 9 (13.2) | 84 (11.2) | 0.51 (0.19–1.34) | 0.17 | ||

| >42 years | 11 (16.2) | 73 (9.8) | 0.75 (0.29–1.90) | 0.54 | ||

| Malea | 59 (85.5) | 524 (70.1) | 2.52 (1.27–5.02) | 0.007 | 2.23 (1.07–4.63) | 0.032 |

| Drivera | 58 (84.0) | 525 (70.3) | 2.25 (1.16–4.37) | 0.014 | 2.11 (1.05–4.27) | 0.037 |

| Driver licensea | 9 (15.5) | 65 (9.4) | 1.76 (0.83–3.75) | 0.14 | ||

- a Variables with P < 0.2 and age group were included in multivariate analysis. (Note: inclusion of all variables resulted in the same model).

- Variables with P ≥ 0.2 in univariate analysis were no helmet use, alcohol consumption, poor weather, time of the day and time period.

| No helmet (%) | Helmet (%) | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | |||

| Number | 645 (81.2) | 149 (18.8) | ||||

| Median age (range) | 22 (1–80) | 28 (5–61) | <0.001 | |||

| Age groupa | ||||||

| 1–15 years | 89 (13.8) | 3 (2.0) | <0.001 | 1 | ||

| 16–17 years | 73 (11.3) | 9 (6.0) | 0.35 (0.09–1.37) | 0.13 | ||

| 18–19 years | 100 (15.5) | 10 (6.7) | 0.44 (0.11–1.75) | 0.25 | ||

| 20–21 years | 57 (8.9) | 17 (11.4) | 0.12 (0.03–0.44) | 0.001 | ||

| 22–23 years | 67 (10.4) | 18 (12.1) | 0.16 (0.04–0.59) | 0.006 | ||

| 24–27 years | 74 (11.5) | 16 (10.7) | 0.20 (0.05–0.74) | 0.016 | ||

| 28–33 years | 65 (10.1) | 27 (18.1) | 0.10 (0.03–0.35) | <0.001 | ||

| 34–42 years | 59 (9.2) | 29 (19.5) | 0.09 (0.03–0.32) | <0.001 | ||

| >42 years | 60 (9.3) | 20 (13.4) | 0.12 (0.03–0.44) | 0.001 | ||

| Malea | 453 (70.2) | 112 (75.2) | 0.78 (0.52–1.17) | 0.23 | ||

| Pillion ridera | 212 (32.9) | 20 (13.4) | 3.16 (1.92–5.20) | <0.001 | 2.72 (1.58–4.68) | <0.001 |

| No driver licensea | 557 (92.5) | 109 (79.6) | 3.18 (1.90–5.32) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.11–3.41) | 0.019 |

| Alcohola | 310 (48.4) | 61 (40.9) | 1.36 (0.94–1.95) | 0.099 | 1.87 (1.24–2.83) | 0.003 |

| Time perioda | ||||||

| December 2007–December 2008 | 472 (73.2) | 100 (67.1) | 0.004 | 1 | ||

| December 2009–January 2010 | 73 (11.3) | 10 (6.7) | 1.14 (0.54–2.41) | 0.73 | ||

| December 2010–January 2011 | 100 (15.5) | 39 (26.2) | 0.54 (0.33–0.87) | 0.012 | ||

| Occupationa | ||||||

| Student/pupil | 263 (40.8) | 33 (22.1) | <0.001 | |||

| Farmer | 166 (25.7) | 37 (24.8) | ||||

| Government employee | 66 (10.2) | 45 (30.2) | ||||

| Worker | 89 (13.8) | 9 (6.0) | ||||

| Vendor | 23 (3.6) | 8 (5.4) | ||||

| Police | 12 (1.9) | 7 (4.7) | ||||

| Soldier | 12 (1.9) | 2 (1.3) | ||||

| Other | 11 (1.7) | 6 (4.0) | ||||

| Unknown | 3 (0.5) | 2 (1.3) | ||||

- a Variables with P < 0.2 plus male sex were included in multivariate analysis.

- Variables with P ≥ 0.2 in univariate analysis were poor weather, time of the day and district Namtha.

Reasons for driving without a helmet

A total of 201 patients could be included in the additional survey. Ten patients were excluded because of death (3), unconsciousness (1), no consent (2), no answer regarding helmet use (2) and loss of data (2). Most patients were male (71.6%) and young (median age 22 years, range 14–65). Main reasons for not wearing a helmet were not possessing a helmet and being pillion passenger (Figure 3). Factors associated in multivariate analysis with not wearing a helmet were pillion riding (OR 7.74, 95% CI 3.49–17.2) and alcohol consumption (OR 2.08, 95% CI 1.09–3.97).

Combination of hospital and police data

Of 1074 patients, 28% (299) reported police investigations. This proportion was highest in the last survey period (39% vs. previous surveys 27%, OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.24–2.44). RTI with bigger vehicles had the highest rates of police investigation (trucks 5/10 and buses 19/20). Police reported 340 RTI, including 10 deaths in 2008. Hospital's numbers were twice as high (695). Capture–recapture analysis estimated 1379 RTI (95% CI 1188–1570). Deaths were estimated at 17 in 2008 (95% CI 7.6–27). RTI mortality rate for the whole province was calculated as 11.6 per 100.000 population (95% CI 5.1–18.1 per 100.000).

Discussion

The study reveals a much higher burden of RTI than officially reported. Most RTI occurred among younger, male and VRU, especially motorcyclists. RTI frequently happened during the evening and Lao New Year. Determinants for serious injuries in motorcyclists were being young, driver and male. Risk factors for more serious head injuries were alcohol consumption, male and no helmet use. Lack of helmet use was determined by pillion riding and alcohol consumption.

Globally, 50% of all deaths are attributed to VRU 4, in the western Pacific, estimates range at 70% 3. In contrast to countries with much higher fatalities among pedestrian such as Bangladesh or India 2, 20, traffic situation and RTI in Laos are more comparable to neighbouring Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand with similarly high rates of motorcyclists 4, 21-25.

The findings for age and gender are in line with the latest global status report on road safety describing RTI as the leading cause of death among 15- to 29-year-olds worldwide and attributing 3 of 4 road deaths to men 4. In Vietnam, rates of injured male RU ranged from 53% to 64% 18, 79% of deaths occurred among male, and 73% were 15- to 49-year-olds 23. Similar rates are reported from bordering Cambodia and Thailand 4. The age group from 15 to 44 years was calculated carrying a disproportionate burden of 69% of disability-adjusted life years lost from RTI in Thailand 26. Studies have shown that younger drivers have higher motivation towards risky driving due to experience-seeking, excitement and sensation-seeking; on the other hand, increasing driver experience leads to less violation of traffic rules 27.

Most accidents in LNP occurred in the evening, especially between 6 and 7 p.m. Studies from urban areas reported later peaks; in Vientiane, at 8–9 p.m. 9; and in Bangkok, at 9–12 p.m. 28. In rural areas, work traditionally starts earlier, and celebrations and ceremonies in LNP typically take place already at lunchtime. Thus, the strongest effect of alcohol-related RTI could be expected on the way back later in the afternoon/evening. Typical timing of police checks during office hours might have further contributed, presuming that increased police patrols reduce alcohol-related RTI 29. The interdependency between celebrations, alcohol and RTI becomes especially obvious during the festival of Lao New Year in April. Similar findings have been reported during the Thai and international New Year celebrations in Thailand. Driving impairment starts at very low blood alcohol concentration, and the accident risk increases rapidly with rising levels 4, 30-32. The alcohol level was not measured in this study, but yearly consumption of pure alcohol in Laos is estimated to be above the western Pacific average at 7.3 l, especially among males (12.5 l; females: 2.3 l) 32. It is common practice to force each other to empty one's glass during celebrations and ceremonies, regardless of driving 6.

Unfortunately, alcohol advertisements in mass media are increasing, the sale of alcohol is mainly unrestricted, no national action plan exists 6, and the legal alcohol limit of 0.08% lacks implementation 4. Further research is needed to find culturally appropriate ways to target drinking and driving in Laos.

The importance of drugs remains unclear. In contrast to alcohol, drug abuse, including amphetamines, is strongly prohibited and socially unacceptable in Laos. Besides hidden drug use, traditional opium consumption is common in certain minority groups 33 and could be underestimated. However, compared to alcohol, psychoactive drug use contributes far less to RTI in Thailand 34.

The surveys identified male sex, being the driver and young age as important determinants for serious injuries in motorcyclists. These risk factors were also frequently reported from the neighbouring countries Vietnam 18 and Thailand 22, 25, 26, 35. The survey set-up could not include speeding as another contributing factor 36. However, in view of its high association with male sex 36, 37, sex presumably also reflects speeding as a determinant in our calculations. Preventive interventions have to target especially younger male drivers.

The striking rate of unlicensed drivers is much higher than that reported from Thailand 38, 39 and requires further attention in multilevel interventions such as education campaigns, scaling up of driver training and licensing courses, and implementation of existing legislation 40, 41.

The study highlights the importance of helmets for injury prevention in the Lao context. The protectiveness of helmets might be underestimated as the variable ‘helmet use’ did not differentiate for safe buckling. Helmet use is the single most effective way of injury prevention in motorbike riders and can reduce head injuries by 69% and deaths by 42% 42. In Vietnam, helmet law implementation has rapidly decreased road traffic head injuries by 16% and deaths by 18% 43. Our study identified pillion passengers as particularly at risk. Facing a huge lack of helmets in 2007, law enforcement targeted drivers only, but has remained unchanged ever since 7. This unfortunate agreement needs urgent revision. Stricter law enforcement could improve financial priority setting of motorcyclists as decent helmets are available for less than 10 USD, at similar expense as being fined twice. Social marketing of helmets, especially in smaller sizes, could help to equip children and teenagers with good-quality helmets 4.

The interpretation and comparison of injury severity in this study is partly limited by the rather general categories without further differentiation between, for example life-threatening and minor fractures. Furthermore, some patients categorised without obvious injuries may have developed symptoms later. Some deaths on the road may not have been transferred to hospital, leading to selection bias.

Capture–recapture analysis proved to be a valuable method for better RTI estimates. It is limited by some partly unachieved underlying methodological assumptions 44, 45. The common subpopulation was not double-checked, but calculations were based on patients' information regarding police investigations that might have started after the interview, possibly leading to overestimation of RTI. Bias from an unequal likelihood of capture between the two samples might occur with different access to the hospital and the police. Independence of sampling was not investigated, for example by stratification of road users 46, and migration may violate the underlying assumption of a closed population. Further studies may validate this approach in the capital city and other resource-limited settings to better guide policy-making. Underreporting of RTI and deaths remains challenging worldwide. Health data have repeatedly questioned validity and accuracy of official reports. In China, numbers from the official death register were twice as high as police data for 2002–2007 47, 48. In Malawi, the capture–recapture method calculated almost 3–4 times higher fatalities than those extrapolated from police data or hospital-based registries alone 46. In Vietnam, police data accounted for only 22% and hospital data for 60% of the combined estimates of non-fatal RTI for 2000–2004 18. Underestimation originates from structural, methodological and practical limitations, such as lack of national surveillance and reporting systems, and use of different definitions 49, but might also derive from fatalistic beliefs explaining road crashes beyond personal control that demand reconciliation without involving the police 50. The influence of beliefs on RTI prevention has not been well studied in most developing countries including Laos, but might be essential for effective road safety campaigns.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study from northern Laos reveals that RTI disproportionally affects young male road users, especially motorcyclists. Further preventive actions need to target these major risk groups and the typical risk factors of alcohol consumption and lack of helmet use. Law enforcement has to be extended to pillion passengers, to drivers' alcohol consumption, and to licensing. Police should expand traffic checks to after office hours especially during Lao New Year. Alcohol abuse needs further political and societal attention. Further studies are needed to develop effective culturally appropriate interventions for road safety in Laos. RTI in northern Laos remain substantially underreported. Combining existing health and police data systematically within a national registration and surveillance system could help to improve RTI data quality from Laos and similar settings, and help to guide resource allocation in preventive programmes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sangkhy Vongsanith, Somkou Kasouvan, Malaythong Kounlavong and Fongsi Cheualuangthan of the team of the NGO Service Fraternel d'Entraide (SFE) for the help with the surveys and data entry and SFE for their financial support. We are very grateful to Rose-Marie Slesak for checking data entry. Our special thanks go to Christa Weichert and the team of Handicap International Belgium (HIB) for their support with the questionnaire and discussions about practical issues. We would like to acknowledge the good cooperation with the Luang Namtha Provincial Government, Traffic Police, Provincial Health Department and Provincial Hospital, especially for providing the RTI data.