The effects, safety and acceptability of compact, pre-filled, autodisable injection devices when delivered by lay health workers

Abstract

enObjectives

To systematically assess (i) the effects and safety and (ii) the acceptability of using lay health workers (LHWs) to deliver vaccines and medicines to mothers and children through compact pre-filled autodisable devices (CPADs).

Methods

We searched electronic databases and grey literature. For the systematic review of effects and safety, we sought randomised and non-randomised controlled trials, controlled before–after studies and interrupted time series studies. For the systematic review of acceptability, we sought qualitative studies. Two researchers independently carried out data extraction, study quality assessment and thematic analysis of the qualitative data.

Results

No studies met our criteria for the review exploring the effects and safety of using LHWs to deliver CPADs. For the acceptability review, six qualitative studies assessed the acceptability of using LHWs to deliver hepatitis B vaccine, tetanus toxoid vaccine, gentamicin or oxytocin using Uniject™ devices. All studies took place in low- or middle-income countries and explored the perceptions of community members, LHWs, supervisors, health professionals or programme managers. Most of the studies were of low quality. Recipients generally accepted the intervention. Most health professionals were confident that LHWs could deliver the intervention with sufficient training and supervision, but some had problems delivering supervision. The LHWs perceived Uniject™ as effective and important and were motivated by positive responses from the community. However, some LHWs feared the consequences if harm should come to recipients.

Conclusions

Evidence of the effects and safety of using CPADs delivered by LHWs is lacking. Evidence regarding acceptability suggests that this intervention may be acceptable although LHWs may feel vulnerable to blame.

Abstract

frObjectifs

Evaluer systématiquement (1) les effets et la sécurité, et (2) l'acceptabilité de l'emploi d'agents de la santé non professionnel (ASNP) pour administrer des vaccins et des médicaments aux mères et aux enfants au moyen de dispositifs compacts pré-remplis, autodestructifs (DCPA).

Méthodes

Nous avons effectué des recherches dans les bases de données électroniques et dans la littérature grise. Pour l'examen systématique des effets et de la sécurité, nous avons recherché des essais contrôlés randomisés et non randomisés, contrôlés avant et après les études et des études de séries temporelles interrompues. Pour l'examen systématique de l'acceptabilité, nous avons recherché des études qualitatives. Deux chercheurs ont indépendamment effectué l'extraction des données, l'évaluation de la qualité de l'étude et de l'analyse thématique des données qualitatives.

Résultats

Aucune étude ne répondait à nos critères pour l'examen explorant les effets et la sécurité de l'utilisation des ASNP à administrer des DCPA. Pour l'examen de l'acceptabilité, six études qualitatives ont évalué l'acceptabilité de l'utilisation d'ASNP pour administrer le vaccin contre l'hépatite B, le vaccin antitétanique, la gentamicine ou l'ocytocine à l'aide des dispositifs Uniject™. Toutes les études ont eu lieu dans des pays à faibles ou moyens revenus et ont exploré les perceptions des membres de la communauté, des ASNP, des superviseurs, des professionnels de la santé ou des gestionnaires de programmes. La plupart des études étaient de faible qualité. Les participants acceptaient généralement l'intervention. La plupart des professionnels de la santé étaient convaincus que les ASNP pouvaient administrer l'intervention avec une formation et une supervision suffisantes, mais certains avaient des difficultés à s'acquitter de la supervision. Les ASNP percevaient Uniject™ comme efficace et important et étaient motivés par des réponses positives de la part de communauté. Cependant, certains ASNP craignaient les conséquences dans le cas de danger causés aux bénéficiaires.

Conclusions

La preuve des effets et de la sécurité de l'utilisation de DCPA administrés par des ASNP est absente. Des preuves concernant l'acceptabilité suggère que cette intervention pourrait être acceptable même si les ASNP peuvent se sentir parfois vulnérables au blâme.

Abstract

esObjetivos

Evaluar sistemáticamente (1) los efectos y la seguridad, y (2) la aceptabilidad de utilizar trabajadores sanitarios legos (TSLs) para entregar vacunas y medicamentos a madres y a sus niños mediante el uso de dispositivos inyectables compactos, pre-llenados y desechables (DCPDs).

Métodos

Realizamos una búsqueda en bases de datos electrónicas y literatura gris. Para las revisiones sistemáticas sobre efectos y seguridad, buscamos en ensayos clínicos controlados, aleatorizados y sin aleatorizar, estudios antes-después y estudios de series temporales interrumpidas. Para la revisión sistemática de la aceptabilidad, buscamos estudios cualitativos. Dos investigadores llevaron a cabo, de forma independiente, la extracción de los datos, la evaluación de calidad del estudio y el análisis temático de los datos cuantitativos.

Resultados

No encontramos estudios que cumplieran con nuestros criterios para una revisión que explorase los efectos y la seguridad de utilizar TSLs para la entrega de DCPDs. Para la revisión de la aceptabilidad, encontramos seis estudios cualitativos que evaluaban la aceptabilidad de utilizar TSLs para la entrega de la vacuna de la Hepatitis B, la vacuna antitetánica, gentamicina u oxitocina mediante dispositivos Uniject™. Todos los estudios se llevaron a cabo en países con ingresos bajos o medios y exploraban las percepciones de los miembros comunitarios, TSLs, supervisores, profesionales sanitarios o gestores del programa. La mayoría de los estudios eran de baja calidad. Los receptores, en general, aceptaban la intervención. La mayoría de los profesionales sanitarios confiaban en que los TSLs con suficiente entrenamiento y supervisión podrían entregar la intervención, pero algunos tenían problemas para realizar la supervisión. Los TSLs percibían el Uniject™ como efectivo e importante, y estaban motivados por las respuestas positivas de la comunidad. Sin embargo algunos TSLs temían las consecuencias de poder hacer daño a los receptores.

Conclusiones

Hacen falta evidencias sobre los efectos y la seguridad del uso DCPDs por TSLs. La evidencia sugiere que esta intervención podría ser aceptable aunque los TSLs pueden sentirse vulnerables al reproche.

Introduction

Many mothers and children are never reached by life-saving health interventions, including vaccines and medicines that are delivered through injection devices. Barriers to access are a critical shortage of health personnel, high costs, recipients' attitudes to certain medicines and difficulties in reaching remote populations. Ensuring access at the time of childbirth can be particularly difficult, especially in populations where many children are born at home. In such contexts, medicines need to be available at community level, outside the health centre, beyond the reach of the cold chain, and at short notice (Creati et al. 2007; POPPHI 2008).

Delegating the delivery of certain vaccines and medicines to first-line, community-based health personnel, sometimes referred to as ‘optimisation’ or ‘task shifting’, could potentially lower some of these barriers. The use of new injection technologies, such as compact pre-filled autodisable devices (CPADs), could enable community-based personnel to provide injectable vaccines and medicines.

We carried out two systematic reviews to assess the effects and safety and the acceptability of using lay or community health workers to deliver vaccines and medicines to mothers and newborns through CPADs. These reviews are two of a series of studies that aimed to inform the World Health Organization's (WHO) ‘Recommendations for Optimizing Health Worker Roles to Improve Access to key Maternal and Newborn Health Interventions through Task Shifting’ (OPTIMIZEMNH) World Health Organization (WHO) (2012).

Development of compact pre-filled autodisable devices (CPADs)

A number of concerns must be addressed before the provision of injectable medicines can be transferred to lower-level, community-based personnel. Some are tied to the practical implications this transfer may have, including logistics and training requirements. Other safety concerns include the potential for errors in dosing, overuse of antibiotics, transmission of infections through syringe reuse and hazardous disposal of used syringes. Developments in injection technology have resolved many of these concerns. CPADs are easy to use, pre-filled and non-reusable, thereby removing the possibility of incorrect doses and minimising the risk of patient-to-patient transmission of bloodborne infections. Compact pre-filled autodisable devices also reduce the burden on logistics systems by making medication, needle and syringe available at the same place and time, and the single-dose design eliminates the wastage associated with multidose vials (PATH 2008). Compact pre-filled autodisable devices have also been successfully used in out-of-cold-chain delivery strategies where the medicine or vaccine they contain permits this (e.g. Wang et al. 2007). Although some problems remain, including the cost of this technology, these other characteristics make it possible for certain vaccines and medicines to be delivered in the community or in people's homes, at short notice, and potentially by lower-level health workers. This technology can therefore play an important role in the feasibility of a task-shifting approach.

The Uniject pre-filled injection system (Uniject™) is currently the most common CPAD on the market, and several international agencies have done much to increase its availability and affordability (e.g. Lloyd 2000; World Health Organization 2000; GAVI 2007). The WHO has pre-qualified both tetanus toxoid and hepatitis B vaccine in Uniject™ (PATH 2008), and plans to use Uniject™ for combination vaccines are also in place (BD 2009). UNICEF has used Uniject™ to deliver tetanus toxoid vaccine to women in Mali, Afghanistan, Ghana, Somalia, Sudan and Burkina Faso. Compact pre-filled autodisable devices are also being used to deliver other applications, including oxytocin for the prevention and treatment of post-partum haemorrhage and injectable contraceptives.

Barriers to the uptake of CPADs

Despite this growing support for CPADs, global institutions have generally refrained from offering guidance about the type of health workers who can deliver these interventions. In some settings, stakeholders may be reluctant to delegate these tasks to lower-level health workers. This may be partly tied to questions about effectiveness and safety and about practical implications, but other issues may also play a part: ‘It seems to be more an issue of policymakers/stakeholders not wanting to potentially “empower” lower-level health workers rather than the technology itself’ (P. Coffey, personal communication). For example, in Indonesia, Uniject™-delivered hepatitis B vaccine has been rolled out nationally for the birth dose (GAVI 2007) and the government now allows trained village-based midwives to deliver this vaccine. This change of practice is not unproblematic, however, and some midwives have indicated that those in charge of implementing the routine immunisation programme have been reluctant to hand over hepatitis B vaccines to village midwives to take back to their work place. ‘Stated reasons for this included a reluctance on the part of immunization staff to allow vaccine outside the cold chain (…) and a mistrust of staff who were not normally part of the immunization programme’ (Creati et al. 2007). In addition, the proportion of births that are attended only by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) would be left without access to vaccinators, as TBAs are not allowed to deliver the intervention (Creati et al. 2007). The use of TBAs to deliver vaccines would require not only change in current policies, which may conflict with government strategies to promote skilled birth attendance, but also the incorporation of TBAs into the health system, allowing them to be trained and supervised, to participate in delivery logistics and to properly register their activities (M. Creati, personal communication).

In addition to policy makers' concerns, the delegation of tasks away from certain groups of health workers and to others has implications for the health workers themselves, for instance, through changes to their workload, social status or payment. Health worker acceptance of the intervention is likely to be key to its success, as is acceptance from healthcare recipients, who may perceive the intervention as an opportunity for increased access to care, but who may also regard task shifting as ‘second-class care’ for the poor (Delorme 2008). Before adopting a health systems intervention such as task shifting, decision makers need information both about the effects and safety of this intervention, and also about the factors that may make it feasible to implement as well as acceptable to key stakeholders.

For the systematic review of effects and safety, our objectives were to assess the effects and safety of using LHWs to deliver vaccines and medicines for maternal, newborn and child health through a CPAD; for the review of acceptability, the objective was to assess stakeholder acceptability of using LHWs to deliver vaccines and medicines through CPADs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for these reviews

Types of studies

For the review of effects and safety, we included the following study designs, as suggested by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) group (EPOC (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group) (2012): randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled trials (NRCTs), controlled before–after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series (ITS) studies.

For the acceptability review, we included studies that reported results of qualitative (text based) data collected through focus group interviews, individual interviews and observation and that focused on stakeholders' perceptions of the acceptability of the delivery of vaccines and medicines through CPAD by LHWs and their experiences and attitudes of this intervention. We accepted varying approaches to data analysis.

Types of participants

For the review of effects and safety, we included studies with the following participants:

- Intervention deliverers: LHWs. We defined the term ‘lay health worker’ as any health worker (paid or voluntary) who performed functions related to healthcare delivery and was trained in some way in the context of the intervention but did not receive any formal professional or paraprofessional certificate or tertiary education degree (Lewin et al. 2005). These comprise community/village health workers, community/village midwives, community/village volunteers, lady health workers/visitors, traditional birth attendants, peer counsellors and home visitors. Health workers with any formal training/degree in their country's context or working in secondary/tertiary level health facilities were excluded from the review.

- Intervention recipients are women of reproductive age group including pregnant women at any period of gestation and babies born at any gestational age.

For the review of acceptability, we included studies of any stakeholder, including intervention recipients, LHWs, supervisors or other healthcare workers, programme managers, representatives of health professional organisations and policy makers.

Types of interventions

For both reviews, we included studies where LHWs delivered any medicine or vaccine (including contraceptives, antibiotics for puerperal sepsis, oxytocin, magnesium sulphate, antibiotics for neonatal sepsis, hepatitis B, other vaccines) through a compact, pre-filled, autodisable injection device such as Uniject™. The medicine or vaccines could be used either alone or in combination.

We excluded from the review those injection systems that were either single use, autodisabled but required filling with the medicine/vaccine (that is, were not pre-filled), or were pre-filled with medicine/vaccine but could be reused (that is, did not disable automatically after single use).

Comparison groups

For the review of effects and safety, we included studies where the intervention was compared with:

- medicine or vaccines delivered by professionally trained health workers through the CPAD injection system or

- medicine or vaccines delivered by professionally trained health workers through the standard injection system used in that setting (for instance, glass syringe/needle or autodisposable single-use syringe/needle) and

- medicine or vaccines delivered by LHWs through the standard injection system.

If the intervention included LHWs working together with professional health workers and did not include a comparison group to enable us to separately assess the effects or safety of the LHWs, the study was excluded.

Types of outcomes

For the review of effects and safety, we included studies with the following primary outcomes: service coverage or utilisation of services: access to injection services or usage/uptake of injection services in the community or continuation rate; and safety of the recipient or LHW in terms of any harm or adverse effect (mild or severe, related to the delivery device) in the recipient and risk of needle-stick injuries in the health worker. Secondary outcomes considered were logistic measures such as storage capacity, time taken for distribution and transport mechanism; waste management; and costs. Because the objective of the review was to assess the effects of LHWs delivering medicine/vaccines through CPADs in terms of better access to services, studies evaluating only the effects of the contained medicine/vaccines were not considered for inclusion.

Search methods for identification of studies

An information specialist developed a search strategy and systematically searched relevant electronic databases (Appendix 1). Every effort was made to collect published or unpublished data from government/non-government organisations and international agencies with experience of implementing the intervention. Reference lists of all included papers and programme reports were also scanned and agencies/authors contacted for any further work. No language restriction was applied.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors assessed independently all titles and abstracts identified. We retrieved full-text copies of the articles identified as potentially relevant by at least one review author. These were then evaluated independently for inclusion by two review authors. If no agreement was reached, a third review author was asked to make an independent assessment. Efforts were made to contact study authors where inadequate information was available from full texts.

For studies assessing effects and safety, we planned to assess the risk of bias using the approach recommended by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) group (EPOC (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group) (2012). For studies assessing acceptability, the quality of papers was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality assessment tool for qualitative studies (CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) (2010).

After reaching agreement on which studies to include, we extracted data on methods, main findings and programme characteristics, including information about programme setting, type of medicine, target group, tasks expected of the LHW, their education level, selection criteria, level of training and supervision and incentives.

The selected qualitative studies were read and reread. Key themes and categories were identified, much as they would be in primary qualitative research. Themes were sought from within the reports of qualitative results and then cross-checked against the domains of interest in a broader LHW review (Glenton et al. 2013) that included themes of: Lay health workers relationships with clients and other health workers; credibility and acceptance of LHWs among different stakeholder groups; incentives and motivation; and training, supervision and ease of use of the medical technology. Searching for themes continued until all the studies were accounted for and no new themes were discerned. One author (CM) had conducted one of the evaluations included in this review (Morgan et al. 2010) . Assessments made in regard to this paper were verified by at least two other authors.

Results

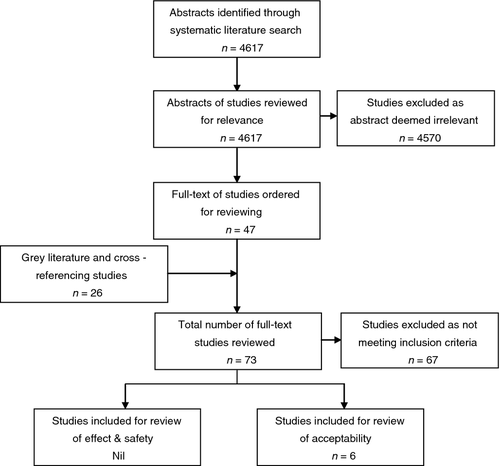

After removing duplicates, our search resulted in a total of 4617 hits. After reviewing titles and abstracts, we retrieved full-text versions of 47 potentially relevant articles. In addition, we retrieved full-text versions of 18 articles obtained from other sources (primarily government/non-government organisations and international agencies such as PATH).

None of the articles met our inclusion criteria for the review of effects and safety (see Table 1). Published papers and programme reports describing six separate programmes met our inclusion criteria for the acceptability review (see Figure 1).

| Study details | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Studies identified through electronic database searches | |

| Bulletin of PAHO 1992 | Brief report, not a scientific article |

| WHO 1999 | Joint statement on use of AD syringes |

| PATH 2001 | Training manual on using AD syringes |

| PATH 2003 | Information on shake test to check vaccine damage |

| MOH Vietnam & PATH 2005 | Study on active management of third stage of labour |

| PATH 2007 | Brief report on Vietnam study (mentioned above, in MoH Vietnam and PATH 2005) |

| Althabe 2011 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Aylward 1995 | Review article |

| Bahamondes 1996 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Bahamondes 1997 | Self-administration with Uniject, not by LHW |

| Balaji 2004 | Topic not relevant, personal opinion on GAVI's role |

| Bergstrom 2001 | Topic not relevant, overview of obstetric technologies |

| Clements 2005 | Personal opinion |

| Darmstadt 2007 | Topic not relevant, on extended interval gentamicin dosing |

| Family H, I. 2007 | Programme update by FHI |

| Fleming 2003 (1) | Status report on Uniject by PATH |

| Fleming 2003 (2) | Guide for programme planners, not a study |

| Fleming 2009 | Study on RUP or AD syringes, not CPAD |

| Geller 2006 | Review article |

| Hall 1998 | Review article on monthly injectable contraceptives |

| Halsey 1989 | Study on Ezeject (plungerless, single-dose syringe), not CPAD |

| Jangsten 2005 | Injection given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Joshi 2004 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Levin 2005 | Cost-effectiveness study on Hep-B |

| Lewin 2010 | Cochrane review article on LHW |

| Miller 2004 | Review article on PPH |

| Muller 1998 | Project report, no relevant information |

| Nelson 2002 | Programme document by PATH |

| Otto 1999 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, outcomes not relevant |

| Paulson 2007 | Study on autoinjector pen and not CPAD |

| Pfutzner 2010 | Study on pre-filled self-injectable pen and not CPAD |

| Prabhakaran 2008 | Personal opinion |

| Ramos 1997 | Study on pre-filled syringes and not CPAD |

| Sharma 2005 | Personal opinion |

| Simpson 2003 | Programme document on Uniject by PATH |

| Stanback 2011 | Topic not relevant (survey of shop operators regarding sale of injectable contraceptives in drug shops) |

| Strand 2005 | Uniject given by professional health workers in hospital |

| Sutanto 1999 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Tsu 2003 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Tsu 2004 | Review article on PPH in developing countries |

| Tsu 2006 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, outcomes not relevant |

| Tsu 2009 (1) | Personal opinion |

| Tsu 2009 (2) | Cost-effectiveness analysis |

| Wang 2007 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Zellner 2004 | Costing study |

| Studies identified through the grey literature and cross-references | |

| Albano 2004 | Study on prefilled self-injectable pen and not CPAD |

| Argentina study, PATH 2009 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| Carville 2011 (draft) | Review article on best practices for preventing perinatal hepatitis B virus transmission |

| Chan 2006 | Cost effective analysis |

| Creati 2007 | Topic not relevant, summary of birth dose Hep-B projects |

| Drain 2003 | Study on AD syringes, not CPAD |

| Guatemala study, PATH 2010; | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

| HealthTech Historical profile, PATH 2005 | Historical profile of Uniject |

| HealthTech report, PATH 2010; | Economic analysis of Uniject-gentamicin for neonatal sepsis |

| Lorenson 2009, PATH | Study not meeting EPOC criteria (time and motion study) |

| Nepal FHP 2010 | Technical brief |

| Nelson 1995 | Study not meeting EPOC criteria |

| Nelson 1999 | Study on Soloshot AD syringes, not CPAD |

| PATH 1996 | Study not meeting EPOC criteria |

| PATH 2003 | Status report on use of Uniject |

| PATH 2007 | Technical brief summarising results of evaluation study in Vietnam |

| PATH 2010 | Report summarising adverse events from Uniject device |

| Prata 2011 | Study of AD syringes, not CPAD |

| REACH 1989 | Field evaluation report of Soloshot AD syringes, not CPAD |

| Stanback 2007 | Study of AD syringes, not CPAD |

| Steinglass 1995 | Study on Soloshot AD syringes, not CPAD |

| Tsu 2009 | Uniject given by professionally trained health workers, not LHWs |

We identified six studies where the use of LHWs to deliver hepatitis B vaccine, tetanus toxoid vaccine, gentamicin or oxytocin through Uniject™ had been evaluated using qualitative data (see Table 2). All had taken place in rural settings in low- or lower-middle-income countries and explored the experiences of intervention recipients and other community members, LHWs, supervisors, other health workers and/or programme managers. The intervention was delivered in the context of a small pilot study organised by the government and at least one non-governmental organisation. In five studies, the LHWs had already been trained in other tasks prior to the pilot study, and the delivery of medicines through Uniject™ had been added to these existing tasks. In the sixth study, TBAs were enlisted to support a tetanus toxoid vaccination campaign, but had not previously been trained in specific health tasks by the government health services.

| Study (Setting) | How the intervention was delivered | LHW background (including selection criteria, education, training, incentives) | Perspectives represented in the study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gentamicin | |||

| Sharma et al. (2010) (Rural Nepal) |

A Female Community Health Volunteer (FCHV) visited newborns immediately after birth in their home and advised the mother to contact her if any danger signs of infection were seen in the newborn. If the FCHV identified one or more danger signs, she provided oral cotrimoxazole-p tablets to the family for dosing at home after observing the administration of the first dose dissolved in breast milk and then administered gentamicin-Uniject™. FCHVs were fully supervised during their first case and were then certified competent to give injections after this first case had been observed. In subsequent cases, the first dose was unsupervised but later doses were supervised |

The Female Community Health Volunteers were local women, a little under half of whom were illiterate or semi-literate, who had been selected by their community. They had previously received a few weeks training to deliver maternal and child health services in their communities, including pneumonia treatment and identification and referral of newborn infection with initiation of treatment with oral cotrimoxazole. They received an additional 4 days of training in the delivery of gentamicin-Uniject™ and essential newborn care. The Female Community Health Volunteers received a small stipend during training and sometimes received small non-monetary incentives in connection with other tasks, but were otherwise unpaid | LHWs (Female Community Health Volunteers), intervention recipients, health workers (supervisors), community leaders |

| Tetanus toxoid | |||

| D'Alois et al. (2004) (Rural Mali) | TBAs delivered tetanus toxoid through Uniject™ to all women of reproductive age during campaigns | The TBAs were selected from the local community, and a large proportion of them had little or no formal education. Many had previously received some training to deliver other healthcare services and received an additional few hours to 2 days of training in the delivery of TT-Uniject™. They received transport and food during training but were otherwise unpaid | LHWs (trained TBAs), trainers, intervention recipients |

| Quiroga et al. (1998) (Rural Bolivia) | Trained TBAs delivered tetanus toxoid through Uniject™ to all pregnant women during routine antenatal visits. Most TBAs delivered the first two or three injections under direct supervision from a nurse supervisor, then delivered subsequent vaccines alone, although received regular supervision visits | The TBAs were selected from the local community, and a large proportion of them had little or no formal education. Many had previously received some training to deliver other healthcare services and received an additional few hours to 2 days of training in the delivery of TT-Uniject™. No information available about incentives | LHWs (trained TBAs), intervention recipients, supervisors |

| Fleming et al. (2004) (Rural Ghana) | Tetanus toxoid was delivered through Uniject™ to women of childbearing age. About one-fourth of all campaign vaccinations were delivered by TBAs and the rest by trained health workers. The TBAs were supervised during the campaigns, although some TBAs in Ghana did deliver injections without direct supervision | The TBAs were selected from the local community, and a large proportion of them had little or no formal education. Many had previously received some training to deliver other healthcare services and received an additional few hours to 2 days training in the delivery of TT-Uniject™. The TBAs were unpaid | LHWs, intervention recipients, trainers, programme staff |

| Oxytocin | |||

| POPPHI (2008) (Rural Mali) | Matrones working in health facilities delivered oxytocin-Uniject™ to all women giving birth vaginally for the prevention of post-partum haemorrhage | The matrones, also referred to as ‘midwifery assistants’ or ‘auxiliary midwives’, differed from the other LHWs in that they were clinic based and did not necessarily match other common understandings of a lay or community health worker. However, they did fulfil this review's definition of a LHW and were therefore included. The matrones were closely monitored and supervised by midwives, nurses or doctors working at the health facilities. The matrones were expected to have at least 6th grade education and had previously received approximately 6 months training in midwifery skills. They had previously been trained to manage oxytocin through conventional needle and syringe and received an additional two to three hours of training in the delivery of oxytocin-Uniject™. The matrones usually received monthly salaries from the health facility and may also receive informal incentives from their patients. In addition, they received per diem payments during their training in Uniject™ delivery | LHWs (matrones), other health workers, facility managers, pharmacy managers |

| Hepatitis B | |||

| Morgan et al. (2010) (Rural Papua New Guinea) | Hepatitis B vaccine was delivered through Uniject™ to all newborns within the first 24 hours of birth. The vaccine was delivered at recipients' homes or at the clinic by Village Health Volunteers. The volunteers delivered the vaccines without direct supervision but received supervision from project officers about once every one to 3 months | The volunteers were already working as either village birth attendants (in which case they were all female) or, less commonly, providing other community health services (both men and women). All had basic literacy and had been selected by their community in collaboration with the NGO responsible for the programme. The volunteers had previously received approximately 6-week training to deliver other healthcare services, including health education, birth attendance and the distribution of antimalarial medication, antibiotics or contraceptives and had received an additional one-day training in the delivery of hepB-Uniject™. The volunteers received food and accommodation during training, and some received small stipends or commodities such as soap, salt and pens from their local governments, but were otherwise unpaid | LHWs (Village Health Volunteers), health centre staff, health managers |

Most of the studies were not designed as stand-alone research studies but were evaluations of the deployment of Uniject™ as part of health development activities and were often not designed to answer specific questions on acceptability. In general, the studies suffered from poor description of study methods, poor use of qualitative data analysis and an insufficient description of results. One exception to this was the study from Nepal (Sharma et al. 2010) , which had a clear description of data collection methods and analysis and a more comprehensive presentation of findings.

Programme acceptability among programme planners and policy makers

None of the studies directly reported qualitative data on programme acceptability among central programme planners or policy makers. Authors in two of the reports, from Ghana and Mali, described what appear to be their own experiences of policy makers' initial scepticism towards allowing TBAs to deliver tetanus toxoid vaccines (D'Alois et al. 2004; Fleming et al. 2004) . Authors describe widespread concern within the Ghana Health Service (GHS) that training TBAs to inject would encourage them to act as ‘doctors’ and allow them to assume that they could also give other injectable medicines, noting widespread public availability of injectable medicines and syringes for purchase in Ghana. A lack of TBA supervision combined with the fact that TBAs are not officially paid by the GHS implied that there would be a strong financial impetus for Uniject™-trained TBAs to begin offering injections to their clients. ‘These fears were discussed in length with the GHS and UNICEF in both districts with a final consensus being (i) that only “responsible” TBAs would be invited to the training, (ii) a clear distinction would be made between Uniject™ and regular syringes during the training, and (iii) TBAs would be strongly discouraged from identifying themselves as qualified general injectors’ (Fleming et al. 2004). In Mali, the initial plan was to have the TBAs provide tetanus vaccination during community-based pre-natal care visits. However, because of concern among policy makers that TBAs would not be able to correctly deliver TT-Uniject™, it was decided that they would administer it during a campaign under strict and continuous supervision of health personnel before considering TBA participation in routine administration of tetanus vaccine (D'Alois et al. 2004).

Programme acceptability among members of the community

Community-based services can increase community acceptance

Community acceptance of oxytocin-Uniject™ when delivered by matrones in Mali was not assessed. However, the delivery of gentamicin, tetanus toxoid and hepatitis B through Uniject™ by LHWs was generally reported as being acceptable to community members (Quiroga et al. 1998; D'Alois et al. 2004; Fleming et al. 2004; POPPHI 2008; Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010). In Ghana, most clients felt that TBAs were either as good as or better than health professionals at delivering the TT-Uniject™, although a small numbers of clients were hesitant to be injected with TT-Uniject™ as they were concerned about the skills of the TBA and preferred a health professional (Fleming et al. 2004). In Nepal, Female Community Health Volunteers reported that all types of people came to them for treatment services, although poorer families were more likely to come than wealthier families. (Sharma et al. 2010). Reasons given for this widespread acceptance were tied to the community-based nature of the programme, implying short distances to treatment, availability of treatment at any time and the availability of treatment in the home (Sharma et al. 2010). This latter aspect was pointed to as being particularly important in cultural systems where the newborn should not be taken out of the home for the first few days after birth (Sharma et al. 2010). In Mali, authors described how one of the assumed advantages of involving TBAs in vaccine delivery was ‘that their social status and communication with women and community leaders might reduce social resistance to vaccinating women, a recurring problem in specific areas of Mali’ (D'Alois et al. 2004).

Involvement from health system and from community leaders can increase community trust and support

Community members also appeared to trust in the knowledge and skills of the LHWs (Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010) and in their ability to deliver the medicine correctly (Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010). In Nepal, the support the Female Community Health Volunteers received from the health facility was said to strengthen this trust (Sharma et al. 2010). Volunteers also noted that the presence of supervisors during administration of gentamicin-Uniject™ appeared to enhance the trust among community members (Sharma et al. 2010). In Ghana, TBA involvement in the vaccination programme ‘definitely increased the status of TBAs by integrating them into a very public aspect of the provision of health services, in a sense, legitimizing them in the eyes of (health workers) and the community’ (Fleming et al. 2004). In Papua New Guinea, trust and community support appeared to have been strengthened through community involvement in the programme. Here, training took place at the local health centre and local community leaders were invited to participate. This was said to enable a greater sense of community ownership, and local leaders felt both included and grateful that an ‘event’ was taking place close to their villages (Morgan et al. 2010).

Programme acceptability among supervisors and other health staff

Sufficient training and supervision of LHWs can increase acceptance among other health workers

Other health workers working alongside or supervising LHWs were also reported as showing high levels of acceptance (D'Alois et al. 2004; Fleming et al. 2004; Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010). Generally, these health workers agreed that the LHWs were able to manage Uniject™ supplies and provide a safe injection (Fleming et al. 2004; Morgan et al. 2010), particularly in the context of routine vaccination (D'Alois et al. 2004) and provided there was sufficient training and supervision (Morgan et al. 2010). Some health workers thought that it would reduce their own workload, allowing them to do other tasks (D'Alois et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2010); could lead to wider coverage and prompter treatment for recipients with the services brought closer to home (D'Alois et al. 2004; Sharma et al. 2010); and could increase community acceptance of local LHWs (Morgan et al. 2010). There was, however, some concern among a minority of health workers regarding whether LHWs could give a vaccination injection correctly. Some were also concerned that LHWs could be subject to legal action if patients were harmed (Morgan et al. 2010).

Health professionals in Nepal saw LHW supervision as important, and the Female Community Health Volunteers themselves noted that supervisors were willing to conduct observation visits in the home even on holidays or when they did not have a vehicle (Sharma et al. 2010). However, some supervisors reported difficulties in carrying out this task, such as difficulties with managing time, transportation costs, communication costs (using their personal cell phones) and lack of simple commodities such as soap for handwashing in caretakers’ homes. Political strikes, lack of transportation or long distances also caused difficulties (Sharma et al. 2010).

Programme acceptability among the LHWs

Ease of use can increase LHW confidence

The LHWs themselves felt positively towards Uniject™, describing it as an effective and important device (Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010) and leading to happy caretakers (Sharma et al. 2010). Lay health workers regarded Uniject™ as easy to use, carry, store and dispose of and were generally reported as being confident in their ability to use the device safely and correctly (Quiroga et al. 1998; Fleming et al. 2004; POPPHI 2008; Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010).

Expansion of tasks can increase community support and LHW motivation

In most programmes, the delivery of medicines through Uniject™ was added to LHWs' existing tasks, usually without additional incentives other than small training stipends. Nepal's Female Community Health Volunteers pointed to the practical limitations of having to deliver gentamicin over a 7-day period, meaning that they were not able to leave the area during this period (Sharma et al. 2010) and that they had to travel to the home of the infant each day: ‘It takes 2–3 h to go for treatment. So we have to adjust the time from family work' (Sharma et al. 2010). However, apart from this feedback, LHWs did not appear to perceive their new tasks as an extra burden or an unreasonable addition to their workload (Morgan et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2010), but instead viewed them positively. In Papua New Guinea, many village health volunteers cited the task of providing vaccination with the CPAD as an additional motivation to visit a family on the day of childbirth (Morgan et al. 2010), and some volunteers requested other medicines, including oxytocin, to be made available through Uniject™ (Morgan et al. 2010). In Bolivia, TBAs who had not had previous injection experience said that they felt increased respect and acceptance from the communities in which they worked during the Uniject™ trial. The TBAs also reported increased satisfaction and efficiency in their work due to their clients' favourable opinions about Uniject™ (Quiroga et al. 1998).

Expansion of tasks can give new concerns and responsibilities

This positive attitude was sometimes, however, accompanied by concerns about what could go wrong. One Female Community Health Volunteer ‘Could not sleep whole night after giving the first dose, but after second dose, baby was well and I felt relieved … since then I am confident’ (Sharma et al. 2010). Other volunteers delivering gentamicin-Uniject™ were afraid that the injection would be given in the wrong location or would result in a wound or local infection; that the full treatment could not be given to the newborn because the volunteer or the newborn was not at home; that the baby's health would not improve after the first injection; and that the family of the sick newborn would be unhappy or dissatisfied if the health of the newborn did not improve or that giving seven injections would harm the newborn. Volunteers were also concerned about their liability if the baby they are treating dies. One volunteer said: ‘I was worried because if something goes wrong, then what the community will say?’ (Sharma et al. 2010).

Similar concerns were voiced in Papua New Guinea. One of the review authors (CM), who was also involved in this study, reports that the concerns of the village health volunteers were met by providing them and village leaders, with a copy of a letter of formal authorisation from the National Department of Health.

Previous experience and current training can increase LHW confidence

In Ghana, TBAs appreciated the fact that the use of TT-Uniject™ did not require any formal education and felt that the training they received was sufficient (Fleming et al. 2004). However, some did suggest that the amount of training was extended and a refresher session was added as the original training occurred 2 months before the actual campaign activities (Fleming et al. 2004). In Nepal, Female Community Health Volunteers attributed their confidence in delivering gentamicin-Uniject™ to their previous training in weighing babies and to the colour-coded systems they used to determine the correct doses (Sharma et al. 2010).

Supervision can increase LHW confidence

Although Female Community Health Volunteers in Nepal unanimously agreed that using gentamicin-Uniject™ was easy, they also appreciated the support given to them by their supervisors, especially during their initial use of the device (Sharma et al. 2010). Many volunteers stated that the presence of the supervisor helped them overcome their initial fear and anxiety (Sharma et al. 2010).

Community support can motivate LHWs

Community support was underlined as important by village health volunteers in Papua New Guinea. The volunteers asked for project advocacy to increase recognition of and support for their work by the community and village leadership. Including village leaders as observers in later training courses was one response. VHVs reported some tangible improvement in support, such as community provision of storage for medical supplies, and this support was viewed as one of the more important motivators of LHW activity (Morgan et al. 2010).

Discussion

Although we identified a handful of studies that addressed the effect and safety of Uniject™ delivered by LHWs, none met our minimum quality criteria. We need to conduct good-quality trials evaluating the effects and safety of vaccines and medicines when delivered by LHWs using CPADs compared with existing delivery mechanisms, including health professionals using CPADs or LHWs using conventional syringes and needles.

In assessing the acceptability of Uniject™ delivered by LHWs, we included six evaluations. The quality of this evidence was mostly low, often with sparse descriptions of stakeholder experiences and perceptions, although one evaluation (Sharma et al. 2010) provided relatively detailed descriptions. Nevertheless, the studies provided sufficient data to gain some insight into acceptability issues. The credibility of these findings is strengthened by the fact that they are consistent across the included studies. Also, our conclusions are concordant with those from another, broader systematic review of qualitative research exploring stakeholder perceptions of LHW programmes for maternal and newborn health (Glenton et al. 2013).

Our review suggests that recipients generally accepted the delivery of vaccines and other medicines by LHWs through Uniject™, although this was not assessed for oxytocin. Recipients appeared to appreciate this increased access to treatment and to have confidence in the knowledge and skills of the LHWs, a response that is also found in the broader systematic review (Glenton et al. 2013). However, it is not completely clear from the studies whether recipients would have received these services from other healthcare workers if the LHW programme had not existed. It is possible that recipients respond more positively to LHWs who represent an actual expansion of healthcare services than to LHWs who only represent a change in the type of healthcare worker.

Both the current review and the broader LHW review conclude that LHW credibility can be strengthened and enhanced by visible collaboration and support from health services and community leaders. However, the broader review points out that this support may be influenced by the degree to which health system and community leadership structures are respected and/or have authority among community members (Glenton et al. 2013).

None of the studies explored the views of professional associations regarding the use of Uniject™ by LHWs, and we can therefore draw no conclusions about the presence or absence of organisational resistance. Our review suggests, however, that individual health professionals working alongside the LHWs generally accepted the intervention. These professionals were generally confident that LHWs could deliver the interventions safely and effectively, providing they had sufficient training and supervision. However, the ability to provide proper supervision was sometimes reported as difficult. That such difficulties were reported at the pilot stage of programmes, where particular attention and resources are likely to be in place, should raise concern.

Issues concerning the acceptability of the intervention to the LHWs themselves are perhaps the most important review finding. Lay health workers were generally positive regarding the technical delivery of medicines through Uniject™. This is a device that they find easier, faster and more convenient than standard approaches to injection, as do professional health workers (PATH 2010), and the LHWs universally accepted and welcomed the task of providing injections with it. Lay health workers have provided a variety of oral medicines, including curative care, in many settings (Haines et al. 2007), and our findings show little resistance among LHWs to provision of an injectable. This was also true in those sites where the LHWs were not previously trained to provide curative medicines.

The social implications of LHWs providing such services pose several challenges. The broader LHW review points to feelings of frustration and impotence among some LHWs who felt unable to meet the needs of community members and who called for opportunities to practice what they considered to be ‘real medicine’ (Glenton et al. 2013). In the current review, LHWs delivering Uniject™ perceived the interventions as effective and important and were motivated by the positive responses of the community. However, some LHWs described concerns about what would happen if things went wrong. The implications of blame and guilt are likely to be far more serious for health workers living and working within their own community than for other health workers and could potentially threaten the credibility and motivation of the individual LHW as well as the credibility of the programme as a whole. Although not easy to provide at scale, high-quality training, frequent supervision and also visible support from community leadership structures are likely to be vital in preventing mistakes as well as protecting the LHW from undeserved blame.

Increased incentives were rarely offered for the delivery of these new tasks, but the studies show no consistent link between this and LHW motivation. Lay health workers may have a number of often intertwined motives, intrinsic and extrinsic, monetary and non-monetary (Bhattacharyya et al. 2001; Glenton et al. 2010). It is possible that tasks that seem inherently powerful or symbolic (as injections often do) can lead to increased motivation and can help to legitimise the LHW's role as a health provider. As motivating factors are likely to be context specific, however, programme planners need to explore and understand the LHW expectations and motivations if low attrition and high performance are to be achieved.

The potential burdens of these new tasks may vary by the type of vaccine or medicine being provided. While vaccines and preventive oxytocin require provision to all eligible clients, significant additional skills in case management are required of LHWs trained to administer gentamicin for newborn sepsis, as in Nepal (Sharma et al. 2010). Despite these differences, we found no clear distinction between the acceptability of curative applications of Uniject™ by LHWs, as compared to preventive. For applications around the time of birth, there is a generally increased risk of incidental morbidity and mortality at this point in the life cycle, with the potential to blame the LHW for poor outcomes that are inappropriately attributed to the treatment given. Although this was raised as a concern in some cases, this issue was not pursued in any detail in these studies.

The likely acceptability of delegating injection responsibilities to LHWs may also vary according to the context in which it is delivered. For example, the use of LHWs in connection with a public health campaign, such as that for tetanus vaccination (Mali and Ghana), or in difficult settings with poor access and very high mortality rates, such as in Nepal, Bolivia and PNG, may be seen as more acceptable by policy makers. A clear need to expand access to injectables, such as critically low coverage, is likely to be needed to justify policy innovation of this nature.

There were several instances where the studies only began to open up valuable lines of enquiry. For instance, in Ghana, authors reported that policy makers were concerned that training TBAs to deliver Uniject would lead them to TBAs' unregulated use of other injections (Fleming et al. 2004), perhaps not an unreasonable concern in a context where syringes and medicines are easily available and where TBAs are not officially paid. Unfortunately though, no attempt was made to explore TBAs' own views or actual practices. Likewise, in Mali, authors referred to vaccination resistance in the community because of fears that the vaccines were a hidden form of family planning. Again, they did not use the qualitative interviews as an opportunity to explore whether use of local vaccinators had an impact on these fears or whether the vaccinators themselves shared these fears. Future research should explore these issues more fully.

Conclusion

When shifting tasks from one health worker cadre to another, it is critical to examine whether this practice is effective and whether this practice is acceptable to all stakeholders. At present, although the Uniject™ device itself has met international safety standards, evidence for its effectiveness and safety, when used by LHWs, is lacking. Evidence for the acceptability of CPADs when delivered by LHWs suggests that this form of task shifting is broadly acceptable, but more rigorous evidence on acceptability is still needed. This could be achieved by more well-conducted project evaluations. In addition, researchers need to broaden their focus to include stakeholders beyond the service delivery level, including professional organisations and policy makers.

The expansion of LHW tasks to include important injectable medicines and vaccines has enormous potential. However, the inclusion of interventions that are increasingly invasive and potentially harmful also has the potential to threaten the stability of programmes that are currently functioning well. Attention needs to be paid to the continued training and supervision of LHWs as their roles are expanded.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Marit Johansen and Miwako Segawa for their help with the development and implementation of the search strategy, Rintaro Mori for providing feedback on the final methodology and search strategy and Metin Gülmezoglu for his help with the development of the review concept. We would also like to acknowledge The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) for their financial support. The Burnet Institute acknowledges the contribution of the Victorian Operational Infrastructure Support Program. In memory of co-author Elin Strømme Nilsen, who sadly died before the publication of this paper and will be sorely missed.

Appendix I

Search Strategy (2011/05/16)

Question: What is the effectiveness, safety and acceptability of drug or vaccine delivered by Uniject compared to other injection devices in a home/community setting or hospital/health facility setting?

Basic Strategy: A OR (B AND C)

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

|

uniject safetject |

auto-disable* cpad disposable non-reusable prefill prefillable pre-filled single-dose single-use |

device* needle* syringe* injection* |

Searched Databases

- EMBASE

- MEDLINE

- CINAHL

- PsycINFO

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

- Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- Health Technology Assessment Database

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database

- POPLINE

- IBECS (Índice Bibliográfico Español en Ciencias de la Salud, Spanish Health Sciences Bibliographic Index)

- LILACS

- WPRIM (The Western Pacific Region Index Medicus)

- AIM (African Index Medicus)

- IMSEAR (Index Medicus for South-East Asia Region)

- IMEMR (Index Medicus for the Who Eastern Mediterranean Region)

Search strategy: EMBASE and MEDLINE (12 May 2011)

| No | Request/hit |

| 1 | uniject OR safetject/33 |

| 2 | (‘auto-disable’ OR ‘auto-disabled’ OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR ‘non-reusable’ OR nonreusable* OR ‘pre-fill’ OR prefill* OR ‘pre-filled’ OR prefilled OR safetject OR ‘single dose’ OR singledose* OR ‘single use’ OR singleuse*):ti:ab/59,675 |

| 3 | (device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*):ti:ab/727,484 |

| 4 | #1 OR (#2 AND #3)/10,156 |

| 5 | #1 OR (#2 AND #3) [humans]/lim/4,149 |

Search strategy: CINAHL Plus with Full Text (on EBSCO) (12 May 2011)

| No | Request/hit |

| S1 | TX (uniject OR safetject)/1 |

| S2 | TI(“auto-disable*” OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR “non-reusable*” OR nonreusable* OR “pre-filled” OR prefill* OR “single-dose*” OR singledose* OR “single-use*” OR singleuse*) OR AB(“auto-disable*” OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR “non-reusable*” OR nonreusable* OR “pre-filled” OR prefilled OR “single-dose*” OR singledose* OR “single-use*” OR singleuse*)/912 |

| S3 | TI(device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*) OR AB(device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*)/12723 |

| S4 | S1 OR (S2 AND S3)/212 |

| S5 | S1 OR (S2 AND S3) (limit to human)/65 |

Search strategy: PsycINFO (on EBSCO) (12 May 2011)

| No | Request/hit |

| S1 | TX (uniject OR safetject)/0 |

| S2 | TI(auto-disable* OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR non-reusable* OR nonreusable* OR pre-filled OR prefill* OR single-dose* OR singledose* OR single-use* OR singleuse*) OR AB(auto-disable* OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR non-reusable* OR nonreusable* OR pre-filled OR prefilled OR single-dose* OR singledose* OR single-use* OR singleuse*)/2493 |

| S3 | TI(device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*) OR AB(device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*)/51117 |

| S4 | S1 OR (S2 AND S3) (limit to human)/99 |

Search strategy: COCHRANE LIBRARY (12 May 2011)

| No | Request |

| 1 | uniject OR safetject [from all text] |

| 2 | (“auto-disable*” OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR “non-reusable*” OR nonreusable* OR “pre-filled” OR prefill* OR “single-dose*” OR singledose* OR “single-use*” OR singleuse*) AND (device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*) [Title, Abstract and Keywords] |

| Each Database on Cochrane Library | [hit] |

| Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Cochrane Reviews) | [13] |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (Other Reviews) | [1] |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Clinical Trials) | [997] |

| Health Technology Assessment Database (Technology Assessments) | [8] |

| NHS Economic Evaluation Database (Economic Evaluations) | [15] |

Search strategy: POPLINE (13 May 2011)

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable* OR autodisable* OR cpad OR disposable* OR non-reusable* OR nonreusable* OR pre-filled OR prefill* OR single-dose* OR singledose* OR single-use* OR singleuse*) AND (device* OR needle* OR syringe* OR injection*))/200.

Search strategy: IBECS (on VHL) (12 May 2011)

Integrated search, field : ‘ALL indexes’.

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable OR auto-disabled OR autodisable$ OR cpad OR disposable$ OR non-reusable OR nonreusable$ OR pre-filled OR prefill$ OR single-dose OR singledose$ OR single-use OR singleuse$) (device$ OR needle$ OR syringe$ OR injection$)).

[limit to human]/11.

Search strategy: LILACS (on VHL) (12 May 2011)

Integrated search, Field : ALL indexes.

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable OR auto-disabled OR autodisable$ OR cpad OR disposable$ OR non-reusable OR nonreusable$ OR pre-filled OR prefill$ OR single-dose OR singledose$ OR single-use OR singleuse$) AND (device$ OR needle$ OR syringe$ OR injection$)).

[limit to human]/44.

Search strategy: WPRIM (12 May 2011)

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable% OR autodisable% OR cpad OR disposable% OR non-reusable% OR nonreusable% OR pre-filled OR prefill% OR single-dose% OR singledose% OR single-use% OR singleuse%) AND (device% OR needle% OR syringe% OR injection%))[all]/75.

Search strategy: IMSEAR (12 May 2011)

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable OR auto-disabled OR autodisable OR cpad OR disposable OR non-reusable OR nonreusable OR pre-filled OR Prefill OR prefilled OR single-dose OR singledose OR single-use OR singleuse) AND (device OR needle OR syringe OR injection))[keywords]/121.

Search strategy: African Index Medicus (12 May 2011)

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable OR auto-disabled OR autodisable$ OR cpad OR disposable OR non-reusable OR nonreusable OR pre-fill OR pre-filled OR prefill$ OR single-dose OR singledose OR single-use OR singleuse) AND (device$ OR needle$ OR syringe$ OR injection$)) [keywords]/0.

Search strategy: IMEMR (12 May 2011)

Request/hit.

uniject OR safetject OR ((auto-disable OR auto-disabled OR autodisable$ OR cpad OR disposable OR non-reusable OR nonreusable OR pre-fill OR pre-filled OR prefill$ OR single-dose OR singledose OR single-use OR singleuse) AND (device$ OR needle$ OR syringe$ OR injection$))[KeyWords]/36.