Illustrating a Splatial Framework to Aging: Absolute, Relative, Relational, and Mental Space in Singapore

Funding: This work was supported by Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE), Singapore, Social Science Research Thematic Grant (MOE2019-SSRTG-012).

ABSTRACT

Understanding the interactions between older adults and their living spaces is an important research topic within the human dynamics of geographical scholarship because of their implications on the quality of aging. The prevailing theory of aging tends to stress aging in place which associates aging well with the home and community, thus inadvertently privileging residential neighborhoods as the focal point where older adults spend most of their time. Recent studies have, however, suggested that older adults also age in (social) networks that extend beyond their neighborhoods' physical locations. The need to incorporate perspectives on aging in networks has challenged the prioritization and the enforcement of absolute (or physical) space in GIS software. This study investigates the potential for integrating four top-level spaces (absolute, relative, relational, and mental) to capture different dimensions of older adults' everyday lives. By leveraging on a dataset of older adults in Singapore, this study demonstrates how the four spaces combined facilitates understanding of aging, specifically their activity spaces, that would otherwise be achieved in a fragmented manner.

1 Introduction

Understanding the interactions between humans and their living spaces has been an important topic in the study of human dynamics with respect to sustainable development and the livability of a city. This is especially true for older adults because having such interactions promotes staying active and healthy aging. The prevailing theories of aging tend to stress aging in place, where it is assumed that older adults engage activities mainly within their residential neighborhoods due to diminishing physical capabilities and sense of attachment (Wiles et al. 2011). Studies, however, have shown that the networks supporting older adults easily transcend their immediate neighborhood (Eliott and Urry 2010; Baldassar et al. 2017; Gao et al. 2024) and thus deserve equal consideration.

The need to give equal attention to both place and network naturally connects to the use of mixed method approaches (Elwood and Cope 2009) in which disparate data sources are assumed to be partial and must be fused to generate deeper insights (Mennis, Mason, and Cao 2013). For example, GPS tracking, diaries, and interviews were used to gain different levels of understanding of older adults' activity spaces and the underlying factors driving the activities (Meijering and Weitkamp 2016). Given the idiosyncratic nature of individual data sources—either quantitative or qualitative, in space or over network, being precise or approximate/vague—how they could be represented as a coherent way for a holistic understanding of older adults' behavior is challenging. At present, common ways to handle these data tend to opt for separate representations, for example, GIS for spatial data with precise geo-references, unstructured text for interview data, and nonspatial databases for survey results. The treatment easily leads to loss of information, or worse misinformation, because of the prioritization of Euclidean geometry in current GIS and the networks in various social relations. Additionally, for understanding how older adults navigate everyday life, the absence of links capturing the relationships between activity space and network leads to disconnectedness between the reasons underpinning decisions in daily routines, such as motivations and perceptions, and older adults' level of activeness and the locations in which activities occur, such as accessing amenities or participating in an event within or beyond their immediate neighborhoods.

The missing links also prompt a consideration of the environment-focused GIS design at present, where the modeling or visualization approaches for representing humans have yet to receive equal attention. In contrast to the natural and built environments, humans have agency and are more dynamic in terms of movement patterns, interactions with the environment, perceptions, to name a few. In addition, individuals may exhibit collective behaviors, which could be properly mined and therefore understood only when they are represented in GIS in an integrated fashion.

This study addresses the issue above by exploring a splatial framework within GIS (Shaw and Sui 2020) that foregrounds the need to consider different kinds of spaces and their linkages to place human at the center of GIS. Through using a dataset of older adults in two communities in Singapore, the paper attempts to illustrate empirically the usefulness of the splatial framework for aging, by addressing the following questions: (1) what is the effectiveness of the splatial framework with different spaces accommodate aspects of older adults' everyday lives, (2) how does multi-space integration under this framework provide insights into their daily activities and the contexts explaining these activity patterns, and (3) how might visualization approaches be operationalized to discover commonalities and diversities in older adults' activities and understand the dynamics of their everyday lives. The subsequent sections engage with examples that were first presented in Gao et al. (2024) and combine it with findings from the survey and GIS analyses to develop the spatial framework introduced in this paper.

2 Spaces in Aging

2.1 Motivating Example

As an older adult who migrated to Singapore at a younger age, Meng (a pseudo name) has mostly engaged in activities in communal spaces within her neighborhood, such as senior activity centers (SACs)1 and food and beverage establishments. Movements between home and other locations are often motivated by social activities within which social networks are constantly being renewed or built. For example, through an invitation by a friend, Meng visited an SAC where new friends were made. The locations brought up were generally with the required precisions even though triangulation from multiple datasets, for example, semi-structured interview and 7-day GPS tracking, is needed.

From a separate data source (i.e., a questionnaire survey), additional information on social connections and community relations of a collection of older adults, including Meng, was collected. For example, the persons they interacted with, their social ties, the locations where interactions took place, and the estimated travel times to reach these individuals, collectively provide measures of personal network. Together with the connections to affinity groups on instant messaging platforms, these sources of information piece together older adults' social connections that might correlate with the self-reported quality of life indicators. Their views of the built infrastructure and the facilities accessed were solicited separately for within and beyond their residential neighborhoods. Within the neighborhood, further information on the interactions with neighbors, their types, and strengths, was solicited.

The example above shows how disparate data sources, each covering specific dimensions of older adults' everyday life, such as the physical locations where social activities take place and social networks which one leverages, provide information only at a specific level of granularity, precision, and completeness. Multi-granularity spatial representations are often needed because of the prevalent use of locational references (e.g., common place names) in the questionnaire survey and interview responses as opposed to a precise location specified in, for example, latitude and longitude, and the qualitative spatial descriptors (e.g., within or beyond neighborhood). Understanding the everyday activities of an older adult therefore requires a GIS design, which recognizes explicitly the intricate relationships of physical locations and social networks and presents them in a unified manner.

2.2 Views of Aging: In Place and in Network

Aging in place, underlain by the idea that older adults' activity spaces are mainly within their residential neighborhoods, has been a prevailing framework for understanding aging and aging well (York Cornwell and Goldman 2021). As such, literature in aging studies has often focused on studying how environmental, technological, or service-related factors could affect successful aging in place (Ahn, Kwon, and Kang 2020). Zhang, Loo, and Wang (2022), for example, examined how the physical and social aspects of neighborhood environment affect life satisfaction, and concluded that place correlates with better overall life satisfaction. Likewise, Stoeckel and Litwin (2015) argued that housing and neighborhood satisfaction contribute to the well-being of older adults, thereby perpetuating perspectives that older adults inhabit box-like containers (i.e., bounded space).

Aging in networks, alternatively, explores aging with an emphasis on the effects of social network on older adults' experiences of aging. Earlier literature that views social network as a form of social capital, albeit not restricted to aging populations, has pointed out that social ties tend to go beyond those formed by kinship relationships and the variety of these ties leads to different social network structures (Wellman, Carrington, and Hall 1985). Recognizing these differences is important as properties of these social ties, for example, tie types, tie strengths, and network members, could individually or collectively condition the level of access to (social) resources (Wellman and Wortley 1990) and thereby affect their health (Umberson and Montez 2010). Entering into the later stage of life, older adults' social networks are likely to have changed because of relocations, degrading health conditions, or change in family compositions. These temporal changes in older adults' social networks could affect, for example, mental health (Litwin and Levinsky 2020) and social lives (Rook and Charles 2017). The use of digital social platforms for social support is more prevalent than expected, and it has been suggested that these platforms offer real supports that “cannot be dismissed as tokens” (Quan-Hasse, Mo, and Wellman 2017). The focus on how social networks affect aging does not necessarily suggest that locations have lost their role in understanding aging. Digital social platforms may in fact reinforce existing social ties beyond neighborhoods. York Cornwell and Goldman (2021) also suggested that neighborhood conditions would structure older adults' access to (local) ties.

The two views, while valid in their own rights, are therefore not mutually exclusive. Neither aging in place nor aging in networks alone could capture the dynamics of aging, and adopting either one view runs the risk of offering a partial picture on aging (also see Ho, Chua, and Feng 2024). An approach that admits both views where their relative importance is case dependent is desirable.

2.3 Human-Centered GIS Framework

Capturing the rich information described in the motivating example, which involves a multitude of geographic spaces, time, and social networks, demands a representational framework that goes beyond the traditional space–time path. Geo-narrative (Kwan and Ding 2008) provided an example along this line of thought, where narratives and multimedia data were linked to movement trajectories and presented in geographic spaces to demonstrate place or environment elicited emotions. While extremely useful as a conceptual framework for understanding a person's sense of place, the space–time path approach is limited in recognizing the social networks that play a crucial role in older adults' engagement in social activities, which are often aspatial or indirectly spatial (e.g., the social network built with neighbors at younger ages). In short, the “interactions” may not always take place in physical geographic space.

Recently, literature in human dynamics has suggested a framework to consider generic interactions anchored on four well-established notions of space: absolute, relative, relational, and mental (Shaw and Sui 2020). The absolute space is based on Euclidean geometry in which geographic locations can be defined either by coordinates or unique identifiers. For the former, which is precise, distance-based geometric properties can be extracted. For the latter, whether the same information can be extracted is dependent on the level of detail of the data. Relative space is related to absolute space but focuses on information within geographic proximity. This space links naturally to the notion of neighborhood where its spatial extent does not have to be precise (Cohen 2017). Relational space captures the relationships between pairs of entities in a geographic space or any conceptual spaces. It is based on connectivity and thus lends itself to graph representation that captures various network types and the information retrieval approaches they afford. Last, mental space captures cognitive attitudes of a person (e.g., perceptions and feelings) toward a location or an entity, which could provide the contexts for understanding the dynamics captured in other spaces. The framework proposed in this paper permits correlations between any pairs of the four spaces so that an integral representation of human dynamics is possible.

We see the potential of this generic framework to go beyond space–time path analyses for comprehending aging holistically. It recognizes the uniqueness of the four spaces both in terms of their properties and the analysis approaches. Yet, being generic, the framework left open the questions regarding how different spaces could be employed to offer an integrated reasoning of elderlies' choices of movements, and capture their activities within and beyond neighborhood. As the input data are often of varying levels of detail due to, for example, perspectives and imprecise spatial references, how could the four spaces be connected in ways that provide useful insights also requires attention.

3 Dataset

The dataset for this study was obtained in two neighborhoods of Singapore with similar demographics but different neighborhood designs, that is, Hougang and Taman Jurong (Figure 1). It was collected using two protocols. The first is a standard questionnaire survey of 1199 older adults (hereafter respondents) aged 60 years old or above in the two neighborhoods. The respondents thus cover a range of older adults that include “young-old” (60–69 years old, 626 persons, 52%), “old-old” (70–79 years old, 429 persons, 36%), and “oldest old” (80–95 years old, 145 persons, 12%) in gerontology literature (Garfein and Herzog 1995). The second follows qualitative GIS approach that involved go-along observations, GPS tracking, and follow-up interviews on a subset of 50 out of the 1199 respondents. The information collected is mostly qualitative in nature and thus less structural than that collected with the first protocol.

3.1 Questionnaire Survey

The questionnaire survey collects information concerning mainly the respondents' social network, community relations, perceived social supports, functional health and co-morbidity, and self-reported well-being indicators. It elicits different aspects of older adults' everyday lives with a focus on how social network and the neighborhood (within and beyond) may play a role in older adults' well-being.

The social network section focuses mainly on each respondent's network quality and their disparity within and beyond neighborhood. Each respondent was asked to provide up to five names whom they contacted to discuss issues of concern, and through the “name interpreter” approach, which is a process that elicits information on the respondent's social network (Chua 2011), provide information that measures the quality of the respondents' ties to each contact and locational information. Parallel to the named contact(s), each respondent was asked to provide information indicative of the roles assumed by their contacts and their affinity group but without specific names. Together, they provide a description of the respondents' social interactions and the possible social capitals they have access to. For specific variables and their meanings, see Table S1 in Supplementary Materials.

The community relations section solicits mainly a respondent's interactions and perceptions of their neighborhood (Table S2 in Supplementary Materials). In addition to the overall satisfaction level of the neighborhood, it collects information on the actual access to amenities and interactions with neighbors, as well as the perception of the neighborhood environment, as indicators of community relations. Specific for access to amenities, this section also collects the reason amenities beyond the immediate neighborhood, if they are indeed being accessed.

In terms of perceived social supports, the survey collects the frequencies of a respondent having meals with or being paid a visit by family members or relatives, as well as phone conversations with friends. To better gauge the quality of social supports, the survey further collects the frequencies of a respondent relies on or opens up to family members, friends, and spouse or partner.

The above information is complemented with health-related information. Functional health and co-morbidity capture the level of difficulties of older adults to perform certain activities of daily living and the disease(s) diagnosed and treated by medical doctors. The two indicators are complemented with information on access to medical facilities, such as polyclinics and hospitals, and other fitness amenities, such as parks and gyms, and access frequency within 1 year. In contrast to the physical health indicators, the self-reported well-being are mental health measures. Six standard dimensions were solicited, which include (1) reduction of work efficiency or activity because of emotional problems, (2) stamina and emotional state, (3) perceived loneliness, (4) perceived isolation, (5) functional health state, and (6) medical condition. Note that perceived loneliness and perceived isolation are related but they look at different aspects of well-being. The former focuses more on the lack of interactions, whereas the latter focuses more on the lack of meaningful and sustained communication.

Although the questionnaire survey focused on social networks and the associated notions such as social ties or capital, it hypothesizes that neighborhood, being a spatially explicit notion in this context, plays a role in aging. Specifically, it distinguishes within and beyond the neighborhood using 20-min walking distance as a threshold for respondents to approximate their neighborhood sizes (LTA 2023).

3.2 Qualitative GIS

A qualitative GIS approach similar to the one used in a previous study on care of older adults (Ho et al. 2020) was adopted to collect both qualitative and quantitative information of a subset of 50 older adults. The approach has its root in qualitative research yet at the same time recognizes the importance of quantitative data and related analytics (Elwood and Cope 2009). In this study, the qualitative and quantitative data are mainly from the interviews of the 50 older adults and GPS tracking.

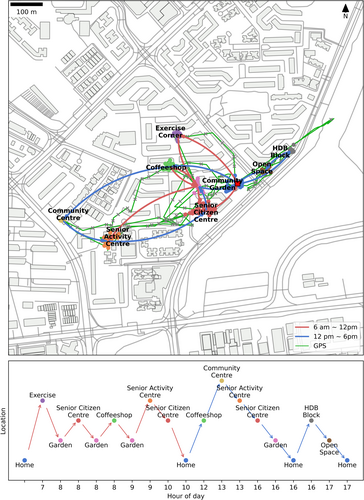

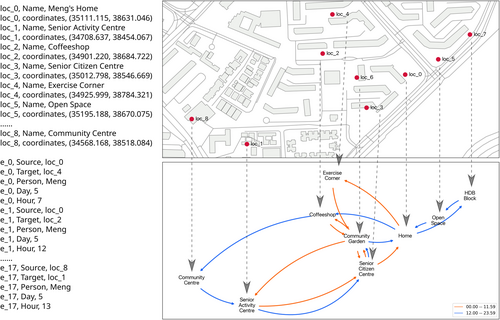

The dataset is collected through a three-stage workflow, which include (1) an opening interview in which basic social networks and mobility patterns of a participant is collected, (2) 7 days of GPS tracking with a 1-day go-along interview to record the week-long loci of a participant and to compliment the tracking effort with additional mobility and social network information, and (3) a concluding interview that, with the help of a map produced from GPS tracking data, elicits a participant's attitudes and feelings regarding daily activities and social networks. Figure 2 shows 1 day of GPS tracking data of an older adult, where it shows the respondent movement was mainly within their neighborhood, thus potentially suggesting an example of aging in place.

The interviews collect information to gain insights into respondents' social routines. More importantly, it solicits information concerning the incentives and preferences to travel to or stay at specific venues and the activities, which are mostly social, engaged at the venues. Precise locational information is available despite that it can be incomplete because some respondents forgot to turn on GPS tracking.

4 Incorporating Information Into Four Spaces

As shown in Section 3, various dimensions of older adults' everyday life are captured at an individual level, regardless of being collected in a structured manner via a questionnaire survey or a more unstructured manner via the Qualitative GIS approach. From a representational point of view, individual older adults are the core entity (with identity) that form the building blocks on which these dimensions are organized and correlated to gain insights into their everyday life. The discussion below on how to leverage the four spaces recognizes the central role of individual older adults, yet at the same time highlights possible links between the four spaces in the human-centered representation.

4.1 Absolute Space

Most places where activities took place or being visited are geo-referenced explicitly either with addresses, postal codes, landmarks, or precise coordinates. These places, which are part of the built environment, have precise presence in physical space with measurable distances and can thus be readily captured in absolute space. Properties, such as the type of a venue or the travel mode of a GPS track, can be captured along with the places because their existence depends on the locations of interest. Once captured, they can be linked to individual older adults through the notion of being located in for identifying the locations of activities, co-locations for measuring potential interactions, spatial clusters, or any operations permitted with Euclidean geometry.

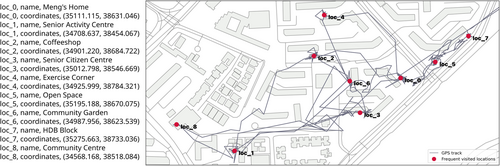

Figure 3 shows locations with geo-references captured in absolute space, using Meng's GPS tracks. It also shows some of the places Meng visited. For each location, we capture minimally the geo-reference in the form of geographic coordinates, and maximally its name as a label, because it is a physical place to which other (three) spaces link.

4.2 Relative Space

Compared with physical locations, the notion of a neighborhood is often subjectively defined. Although the data collected in the questionnaire described in Section 3 impose an operational definition of neighborhood as (an area) within a distance threshold by travel mode, such as 20 min by walking, neighborhood here remains subjective because the threshold is used as a gauge to approximate its physical bound. An area with crisp boundary may therefore claim false precision, and thus would be best recorded as a notion in relative space. Despite being vague in its spatial extent, the notion of neighborhood here is anchored on a location with geo-reference, that is, an older adult's home location, and thus demands a link to absolute space. Note that this way of capturing neighborhood can be extended to include approaches in well-established qualitative spatial reasoning literature (Yao and Thill 2006; Du, Feng and Guo 2015) through links to spaces not necessarily restricted to absolute space.

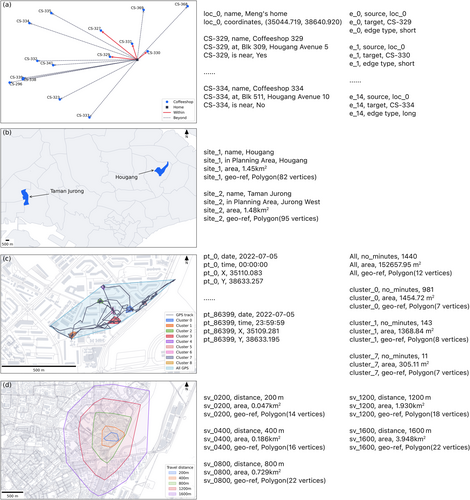

Figure 4 shows an example of a neighborhood in relative space, which is encoded with the neighborhood(geo-reference) function. Figure 4a shows the most primitive form of neighborhood (i.e., the exact area of the neighborhood is not defined) and thus it resides solely in relative space with a conceptual graph that supports only the extractions of within or beyond (neighborhood). In Figure 4b, the neighborhoods of Taman Jurong and Hougang are defined with precise spatial footprints, and thus each has an explicit link to absolute space. Figure 4c shows a dynamically derived activity location obtained from Meng's GPS tracks and the neighborhood Meng engaged activities, both using well-established Euclidean-based algorithms. It demonstrates an example of an explicit link to absolute space where additional operations based on Euclidean geometry can be executed. Figure 4d shows the neighborhood defined by running a typical service area analysis, which links to the relational space described in Section 4.3 below.

4.3 Relational Space

The various relations of individual older adults, including the social networks that connect them to other individuals and community relations, fit squarely within relational space because it captures “how things related to each other” (Shaw and Sui 2020). Intuitively, a social connection between an older adult and a contact forms the atomic entity in relative space, where a pair of nodes representing the older adult and the contact is connected by an edge associated with various properties. These properties can be non-locational, such as relationship type and indicators of tie strength. They can also be locational in absolute space, such as venues where activities are engaged, or in relative space, such as whether a contact lives within or beyond one's neighborhood. Recognizing non-locational and locational properties also allows the distinction of interactions virtually or physically. As indicators of an older adult's social network quality is also solicited at a collective level (Table S1, Supplementary Material), that is, without identifying individual contacts, these indicators are attached to older adults as node properties.

In addition to the social networks of older adults, community relations, or the relationships of older adults with their residential neighborhoods (Table S2, Supplementary Material), form a separate relational space as this type of relationship is between an older adult and the living environment, and thus carries explicit links to both absolute space and relative space. The capturing of the amenity used within an older adult's neighborhood demonstrates this point. Similar to social networks, community relations can carry varying strengths, which indicate closeness of an older adult with the neighborhood. As this piece of information is gathered at a collected level, it is attached to individual older adults as node properties. Furthermore, such type of relationship is often characterized by perceptions of the neighborhood, such as the satisfaction level or the perceived dangerous level of a neighborhood, which suggests the need to extend a link to mental space described in Section 4.4 below.

In contrast to social network and community network, the more tangible mobility network in the form of origin–destination (OD) pairs can also be readily captured in relational space but again in a separate relational space given that mobility analyses are distinct from social network analyses. The mobility network alone enables an understanding of the places visited by older adults. When movement trajectory between two locations is available in the absolute space, an OD can be linked to the trajectory to explore the actual travel path or the physical/built environments along the path. In case precise locations are unknown and thus the link to a location in absolute space is absent, the types of amenities used can still be obtained.

Beyond these three prominent relational spaces above, understanding the everyday lives of older adults may involve other relational spaces. The “decision space” that captures the motivations, incentives, or reasons for older adults to visit a place or to access facilities beyond their residential neighborhood serves as one such example. The relational space here can readily accommodate decision space with potential links to absolute, relative, and other relational space.

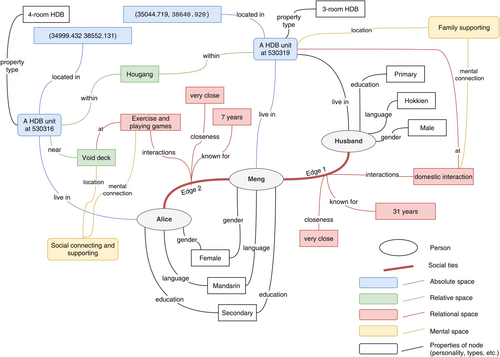

Figure 5 visualizes part of Meng's social network as an example of relational space and links to other spaces. Within relational space, Meng connects to two persons with different socioeconomic status and varying strengths. Moreover, the interactions between two persons, for example, exercise and playing games between Meng and a contact Alice, are captured. The locations where interactions took place could be locations with no precise geo-references in relative space, for example, void deck and Hougang, or those with precise geo-references in absolute space. Last, the kinds of support perceived by Meng are captured in mental space with explicit links to Meng.

Figure 6 shows a second example of relative space, with OD sets derived from their precise geo-references. It demonstrates explicit linkage between relative space and absolute space, while at the same time reasoning about Meng's mobility patterns in the morning and afternoon. These two graphs are kept separate in relational space despite that they both connect to Meng, as the graph in Figure 5 is about social network while the graph in Figure 6 is about mobility patterns. Nevertheless, they both are connected to Meng to capture various kinds of relational spaces that describe Meng's everyday life.

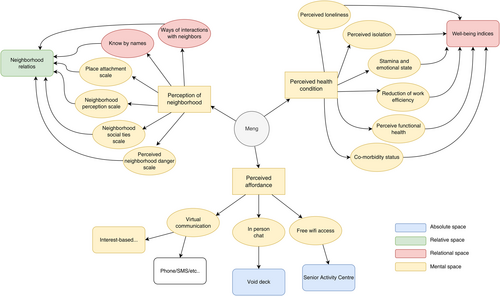

4.4 Mental Space

The dataset collected in the study reflects the older adults' multifaceted perceptions on their neighborhoods and physical/mental health status. The perceptions of the neighborhoods reflect what the respondents have in mind about their built environment, neighbors, or both. Indicators of these perceptions, such as overall level of satisfaction with the neighborhood, the amenities accessed within the neighborhood, or interactions with neighbors are linked with the notion of neighborhood in relative space. The perception of place can be indirectly acquired through the concept related to “perceived affordance,” where in this context is associated with older adults' perception of the services that can be received or interactions engaged at specific venue. The free Wi-Fi access at a community center, for example, can be perceived as a place enabling Internet-based services and thus serves as a motivation for an older adult to go there.

Older adults' physical and mental health, while often being objectively measured, carries a perceptual component. It thus presents an aspect of older adults that straddles between mental space and a second space that most often would be the relational space. Perceived loneliness and perceived isolation, stamina and emotional state, and reduction in work efficiency due to emotional problems are clearly associated with mental space. The functional health and medical conditions are self-described although they can be associated with observable measures, yet they are part of the description of older adults' health status. Capturing these measures in relational space given their association to health status, with links to mental space to capture aspects of perceived health, would appropriately recognize the nature of these measurements.

Within mental space, these perceptions can each be captured as a property associated with an older adult, which may further be confined by a within link to the older adult's neighborhood. Given that the neighborhood notion can be extended to absolute space if the spatial footprint is explicitly defined, the neighborhood in which the perception was developed can be extended similarly.

Figure 7 shows an excerpt of the information captured in mental space. It captures three types of Meng's mental spaces, that is, perceived neighborhood, perceived health status, and perceived affordance. The figure also shows that although a mental space does not occupy physical spaces, it may be related to absolute space (e.g., void deck), relative space (neighborhood), or a conceptual collection (e.g., wellness indices) to be placed in relational space.

4.5 Understanding the Interactions of Older Adults

The four subsections above show how various aspects of older adults' everyday life, which cut across the four spaces, are represented using graphs. These graphs distinguish between the four spaces based on their conceptual differences. The distinction can be clearly seen between Figures 3 and 5 where the former can be readily presented with a cartographic map, whereas the latter is best presented as a graph (or diagram). The distinctions are also made within individual spaces, especially in relational and mental spaces. This ensures semantic precision as different conceptually distinct relational or mental spaces are supported by different sets of operations. Provision for different notions of neighborhood at different levels of details is available to ensure generalizability (Figure 4). These graphs can be used individually or collectively to better understand older adults' everyday lives.

4.5.1 Individual Graphs in One Space

Using individual graphs in one space is relatively straightforward. For example, the activity space of Meng can be easily retrieved from the graph in absolute space. If the precise GPS trajectory is not available, the activity space can also be retrieved from the graphs in either relative space or relational space. Similarly, the sense of place of individual older adults and the motivations to travel to certain places could be extracted from the graph in mental space through the graphs associated respectively with neighborhood relations or perceived affordance in mental space. Note that the graphs here can also be used to specify information extraction pipelines through using published models. One such example is the use of the algorithms in the family of two-step floating catchment area first published by Luo and Wang (2003) to obtain potential accessibility of amenities within the home locations of older adults.

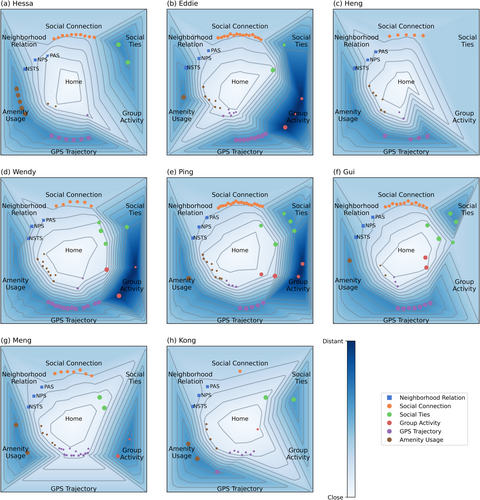

4.5.2 Integrated View of the Four Spaces—Conceptual Landscape

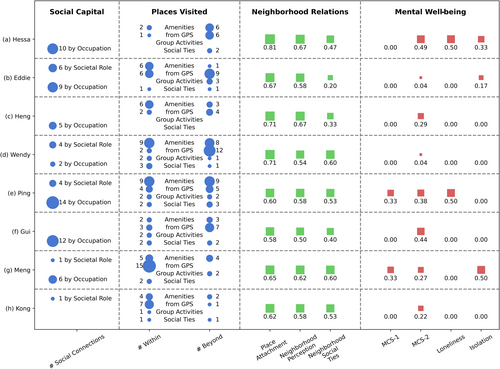

As the graphs are all connected to their respective individual older adults, collectively they enable analyses through an integrated view of the four spaces to understand important interactions, possible reasons for these interactions, and personal characteristics. To enable an integrated view of the four spaces with different characteristics as described in preceding sections, here we employ what we called the conceptual landscape of an older adult. It is a map-like visualization with individual older adults' homes placed at the center, surrounded by the selected dimensions of these older adults. In Figure 8, an example of six dimensions–amenity usage, neighborhood relation, social connection, social ties, group activity, and GPS trajectory—from different spaces is shown although more dimensions can be accommodated if necessary.

The map-like visualization is termed a conceptual landscape because, while presented in a map form, it does not support measurements in Euclidean geometry. Rather, it presents information in multiple dimensions, which are encoded in different spaces, against the notion of neighborhood shown in a gradation of blues. Lighter blues are associated with the notion of neighborhood either physically, that is, within neighborhood, or metaphorically, that is, better connected with one's neighborhood. Conversely, darker blues are associated with disconnectedness with one's neighborhood, again either physically or metaphorically. The interim blue colors indicate that no associations with the notion of neighborhood.

Within the conceptual landscape, dot totals in the same dimension for different older adults may be different depending on individuals' levels of social connections and activities. Figure 8 shows an example based on the eight older adults from our dataset. For example, in Figure 8b,c, for Eddie and Heng, the number of dots in the social tie dimension, which indicate the number of names produced by the two respondents through the name generator in the survey, are two and none. Similarly, for social connections, Eddie remained connected to more people than Heng. Note that they are placed in the interim blue color range as they are not connected to the notion of neighborhood either physically or metaphorically. For the GPS track dimension, Eddie visited more places (14), where Heng visited less spaces (6). The dot sizes for amenity usage and GPS trajectory are scaled according to whether they are within or beyond the older adults' neighborhood. The dot sizes for social ties and group activities are scaled according to the self-reported closeness levels between seniors and their respective contacts and frequency, respectively.

4.5.2.1 Aging in Place or Aging in Networks?

Viewing these dimensions as the conceptual landscape of an older adult brings interesting interpretations. From Figure 8a–h, we see increasingly lighter blue tones on the conceptual landscape. For Hessa and Eddie, their amenity usages and places visited occupy both the lighter and darker blue ranges, suggesting that they took place both within and beyond the neighborhood. Additionally, the neighborhood relationship indicator neighborhood social tie scales (NSTS) extend into the darker blue region, which suggests lower levels of neighborhood attachment for the two older adults, and the named close social ties overlaps in the darker blue region, which suggests that they are from beyond the neighborhood. Together, they demonstrate a pattern closely related to aging in networks because of the co-presence of the mostly beyond neighborhood dimensions and lower neighborhood attachment. Heng's conceptual landscape involves no social ties or group activities and limited social connections. However, the places visited according to GPS trajectory suggest that Heng would travel beyond the neighborhood to engage in activities with (unnamed) friends. As such, Heng's conceptual landscape exhibits a close connection to aging in networks as well.

In contrast, the places which Meng visited and the two named contacts shown in the social ties dimension are both within the neighborhood, and their amenity usage are also predominantly within the neighborhood. Kong exhibits a similar pattern along these three dimensions. Although Meng and Kong have varying social connections and level of engagement of group activities, these dimensions do not affect both respondents' activity spaces. The fact that both respondents' neighborhood relations are (metaphorical) associated with their neighborhoods reflects the strong connections they have to the local communities, which demonstrated an aging-in-place lifestyle.

The conceptual landscapes in Figure 8d–f exhibit patterns that are more-or-less in between the patterns of aging in place and aging in networks. Interestingly, although they mostly access amenities with neighborhood, the places they visited to engage social activities are mostly beyond the neighborhood. The named contacts in the social ties dimension and the group activities are also from both the within and beyond neighborhoods. As such, they indicate a third pattern more associated with older adults aging in both place and network.

4.5.2.2 Alternative Views

The rich information encoded in and the linkages across the four spaces support views alternative to the map-like presentation above to highlight other dimensions of older adults' everyday lives and the finer level of information among chosen dimensions. Figure 9 shows an example that highlights the well-being dimensions of the same sample of respondents shown in Figure 8. The higher the values, the more severe the older adults reported experiencing a challenge in the respective well-being indicator. It also provides a finer level of details on the activity spaces (amenity accessed and visited POI from GPS trajectory) and social connections with explicit differentiation of neighborhood relations.

Focusing on mental wellness, expectedly the alternative view of the eight older adults shows that most have reported negative stamina and emotional state (MCS-2). Reporting negatively on MCS-2 can lead to negative responses to other mental well-being dimensions. Hessa and Ping, who exhibited a lifestyle more related to aging in place and aging in networks, reported comparatively high levels of loneliness, whereas Meng, with a more aging-in-place lifestyle, reported comparatively high isolation. Visually correlating their well-being indicators with the places visited to engage in activities and social ties within/beyond neighborhood, as well as their neighborhood relations, does not reveal a consistent pattern. However, for Hessa and Meng, the relatively high negative reporting on isolation may be related to lower group activities and relatively lower number of social ties within the neighborhood. However, as they have a reasonable amount of interactions with neighbors (neighborhood social ties are 0.47 and 0.60, respectively), it suggests that a necessary condition for older adults to feel isolated is the lack of sufficient number of stronger social ties. One may argue that their online activities can mediate the sense of isolation. From the go-along interview of Hessa and Meng, they both have reasonable levels of online activities, such as regular conversations between family members or time spent on social media platforms (Gao et al. 2024). Yet it is observed that most of these engagements are “passive,” for example, reading announcements of formal courses and group workouts, scan Facebook or Instagram postings, or other informal social events, or individualistic, for example, play online games. Despite Hessa and Meng indicating that they did join social activities based on the information received from social media apps, the role of online platforms appeared to be limited to communicating information and offered a means to encouraging social activities, but it remained inconclusive whether they foster stronger social ties.

For Ping whose lifestyle is more associated with aging in place and aging in networks, his conceptual landscape in Figure 9 showed a relatively high number of places visited, activities engaged, and social ties within and beyond neighborhood. His online activities were similar to that of Hessa's and Meng's in the sense that he communicated with friends and family members on apps, received notifications on social events, and browsed Facebook pages. Yet, his use of online platforms was more “active” because Zoom was used for bible reading sessions. Despite a more active lifestyle either physically or online, Ping reported a relatively high level of loneliness. The result could mean that Ping requires support that goes beyond typical social engagements or the perceived loneliness in fact contributed to a more active lifestyle.

5 Conclusion

Representing the dynamic interactions between humans and their living spaces presents a crucial step toward a better understanding of sustainable development and livability of a city. Capturing such interactions, however, has often been carried out in a fragmented manner. Using datasets collected in two neighborhoods in Singapore, that is, Taman Jurong and Hougang areas, this study explored the potential of a splatial framework, which integrates absolute, relative, relational, and mental spaces in capturing various aspects of older adults' everyday lives and how they may impact their well-being. With a consistent format of triple, it demonstrated that the four spaces are sufficient to capture various dimensions of older adults' everyday lives. By using elevation as a metaphor for distance—lighter tones mean closers or within the neighborhood and darker tones mean farther or beyond the neighborhood—the conceptual landscape shown in Section 4.5.2 demonstrated the usefulness and the need of integrating the four spaces to better understand older adults' everyday lives. The ability to enable proper reasoning either within or across individual spaces is not only useful for understanding the similarities or differences of older adult's life patterns, but also for theorizing how place and (social) network affect successful aging.

Technically, the integration of the four spaces for representing the everyday life of older adults allows for vague or intangible interactions (e.g., social network) to be captured. Being able to do so is often necessary for studies on human, where the information available may be qualitative in nature, and in some cases imprecise. The flexibility of the splatial framework to capture and reason information at varying levels of detail minimizes information loss, which in turn permits a richer description and understanding of older adults' everyday lives.

Practically, the conceptual landscape and its alternative view provide a means to show that older adults in Singapore do not simply age in place or age in networks alone, even though some exhibited stronger aging-in-place lifestyle, whereas others exhibited stronger aging in networks lifestyle. Aging in networks often involves social activities that motivate older adults to go beyond their immediate residential neighborhoods. Such a finding suggests the need in policy to go beyond planning the built environment in older adults' residential neighborhoods and pay more attention to promote social activities, either via formal or informal programming. Correlating with well-being measures, the alternative view of the conceptual landscape showed that some older adults felt isolated despite being actively involved in various social activities. The result further underpins the need for policy to offer opportunities for older adults to stay active and build strong ties by promoting social activities that foster social bonds. Drawing from Ping's case, such activities can be carried out online, yet they have to actively engage a group of participants to be effective.

Although the splatial framework involving the four spaces has been demonstrated to be useful through a case study on older adults in Singapore, its potential is not limited to what is described in this article. For example, while the alternative view of the conceptual space presented narrowed in on mental health, physical health measures including functional health and co-morbidity are captured in relational space. It is complemented with the access to clinics within or beyond neighborhoods in the absolute space. They can be readily incorporated as an additional dimension in the alternative view of the mental space for addressing domain questions, such as whether physical health alters an older adult's lifestyle from aging in place to aging in networks, or vice versa. This work could be further enriched by more complete integration of multimodal information with the help of natural language processing tools, especially on extracting motivations and/or incentives, to provide a more consistent understanding of older adults' decision-making processes that are increasingly conditioned not only by geography but also by networks.

Acknowledgments

This research project is supported by the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its Social Science Research Thematic Grant (MOE2019-SSRTG-012).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting this study cannot be made available for the privacy of the individuals participated in the study.