Skin & SMAS layer remodeling technique (SSRT): Achieving both volume and lifting effects with filler treatments

Abstract

Background

The skin & SMAS layer remodeling technique (SSRT) represents a significant advancement in facial aesthetic treatments. Traditional methods primarily address wrinkles and volume loss, whereas SSRT focuses on achieving both volume and natural lifting effects through strategic filler injections. This technique emphasizes the anatomical and dynamic properties of facial tissues, particularly the SMAS, to enhance facial symmetry and contours while maintaining natural movement.

Materials and Methods

SSRT employs a combination of firm and soft hyaluronic acid fillers to sculpt a youthful, dynamic appearance, simulating the natural lift of a smiling expression. This study explores the effects of gravity on facial tissues and uses advanced imaging techniques to corroborate the shifting of tissues. The technique is compared with other recognized methods, such as true lift and myomodulation, to evaluate its effectiveness in balancing volume enhancement and dynamic facial expressions.

Results

The results indicate that SSRT uniquely balances volume enhancement and dynamic facial expressions, achieving a visibly lifted but natural appearance. The use of advanced imaging techniques substantiates SSRT's effectiveness by showing the shifting of tissues. SSRT reduces the risks associated with excessive filler use and aligns with contemporary aesthetic preferences.

Conclusion

SSRT offers a novel approach by mimicking the facial lift observed when lying down, providing insights into potential transformative “lifts” when upright. By strategically combining firm and soft hyaluronic acid fillers, SSRT achieves a balance of volume and lift, enhancing facial symmetry and maintaining natural movement. This technique represents a significant advancement in facial aesthetic treatments, offering a natural and dynamic alternative to traditional methods.

1 INTRODUCTION

With the increasing clinical application of fillers, there has been a notable shift in the methodologies used for facial rejuvenation and volumization.1, 2 Historically, fillers of varying particle sizes and consistencies were employed primarily to enhance skin quality and address complex areas such as around the eyes and mouth, particularly for various types of wrinkles.3, 4 Recent advancements in fillers characterized by high viscoelastic properties have facilitated a comprehensive approach to sculpting facial contours holistically.5

Globally, there is a discernible transition from traditional dermal fillers towards soft tissue volume fillers, which are now preferred for comprehensive facial contouring.6, 7 This trend is particularly evident in Asia, where surveys indicate a preference for fillers over fat grafting for enhancing facial volume broadly, rather than targeting isolated areas.8-11

Achieving a harmonious and symmetrical appearance necessitates consideration of the face in motion, not merely at rest. This approach requires detailed understanding of the anatomical configuration and dynamic changes of the facial soft tissues overlying the skeletal framework, as well as the age-related transformations these tissues undergo. An accurate facial analysis, aligned with current aesthetic ideals and personalized to individual anatomical nuances, is crucial.

The ideal facial contour, as perceived when smiling, involves a natural upward and lateral pull of the mid and lower facial tissues due to the activation of lip elevator muscles. This dynamic movement creates the illusion of a “lift”, resulting in a narrower, V-shaped lower face with elevated, fuller anterior cheek areas. Emulating these natural soft tissue dynamics during filler application can result in a visage that appears naturally buoyant and youthful.11-13

Moreover, the discourse has evolved from merely augmenting facial volume to strategically achieving a lift. It is now understood that significant facial aging is not only manifested through wrinkles but also through the shifting facial contour, primarily driven by gravitational effects on increasingly lax tissues. This sagging is pronounced while upright but is altered when the orientation changes, such as lying down, as observed through 3D imaging techniques which demonstrate how tissue density increases and sags less in prone positions.14

Therefore, understanding the multifaceted movement and transformation of facial tissues in different orientations is imperative for achieving a truly natural lift. This perspective underpins contemporary filler techniques, such as the SSRT (Skin & SMAS layer Remodeling Technique) developed in Korea, alongside recognized methods like True Lift and Myomodulation, which all aim to harness these dynamics for enhanced facial aesthetics without adverse effects.

1.1 SSRT (skin & SMAS layer remodeling technique)

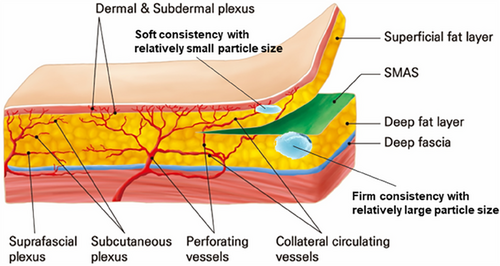

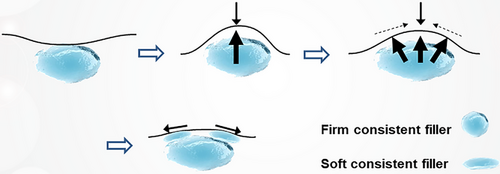

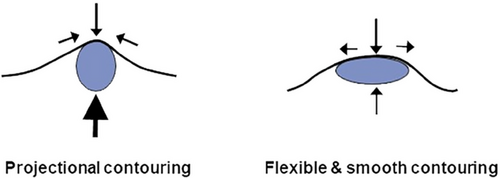

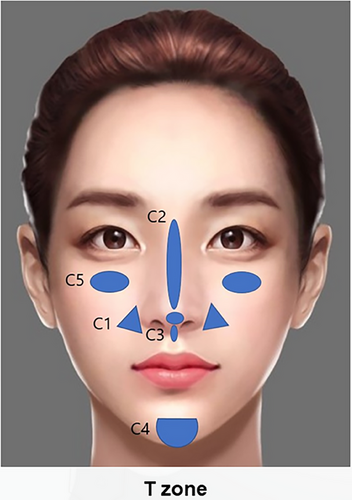

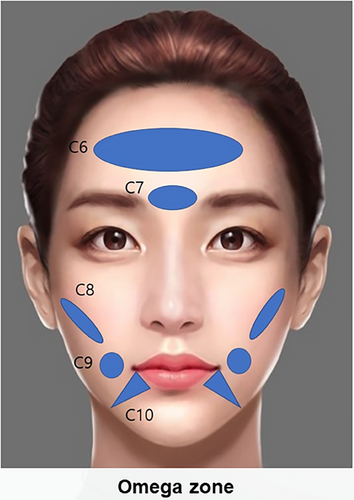

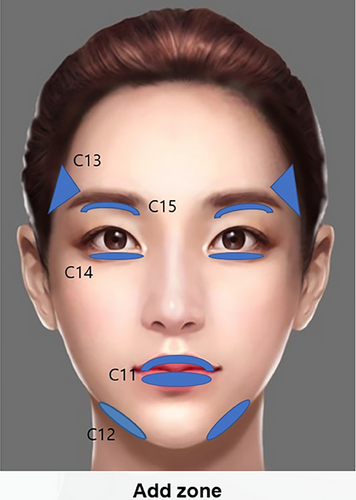

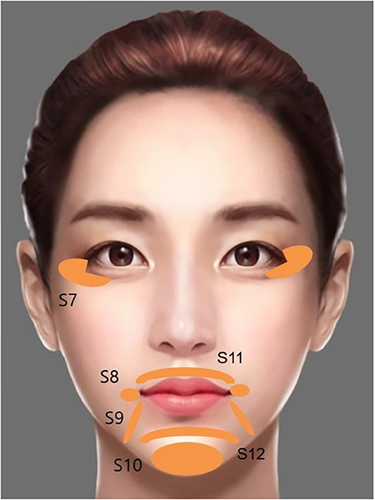

The innovative Skin & SMAS layer Remodeling Technique (SSRT) introduced by the author represents a paradigm shift in the application of hyaluronic acid (HA) fillers, advancing beyond traditional methods primarily focused on volumizing and wrinkle reduction. This technique categorizes HA fillers into two distinct groups based on their physical properties: firm fillers characterized by their denser consistency and larger particle sizes, and soft fillers, which are more malleable and feature relatively smaller particle sizes.15-17 The selection criteria for these fillers extend beyond mere tactile perception; they consider the intended depth of injection, specific facial regions targeted, and the overall aesthetic objectives intended by the treatment (Figure 1).

By integrating a strategic mix of these different types of HA fillers, tailored to suit the unique requirements of various facial areas and the specific layers within the skin and subcutaneous tissues, practitioners can achieve more than just facial volumization.18 The technique is designed to elicit a comprehensive skin-lifting effect, sculpting a naturally appealing V-shaped or heart-shaped facial contour that mimics the appearance of a smiling face. This approach not only enhances the aesthetic quality of the face but also supports dynamic expressions, contributing to a more youthful and animated appearance.

However, it's important to address misconceptions regarding the effects of filler treatments. Some critics argue that fillers merely puff up the face, creating an unnatural and balloon-like appearance that can make the skin appear overly taut and the facial structure awkward during expressions.19, 20 While there is a kernel of truth in these concerns—particularly when excessive volumes are used—the SSRT method mitigates such outcomes by judiciously varying the consistency of the fillers used. This approach ensures that enhancements contribute to the facial structure without the drawbacks of excessive volumization, thus reducing the potential for complications associated with overuse of fillers.

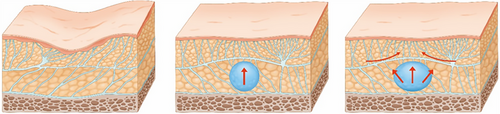

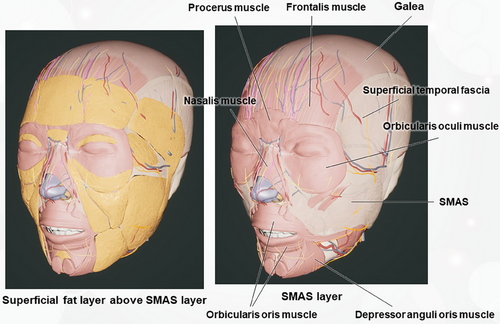

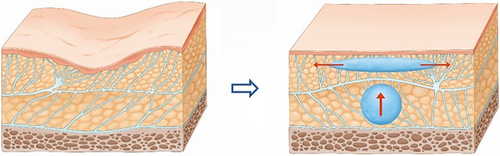

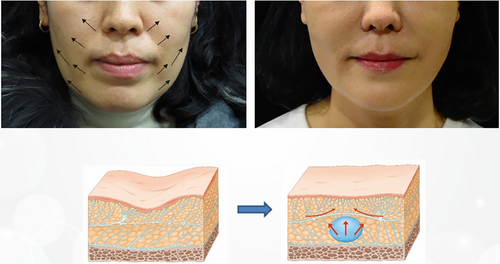

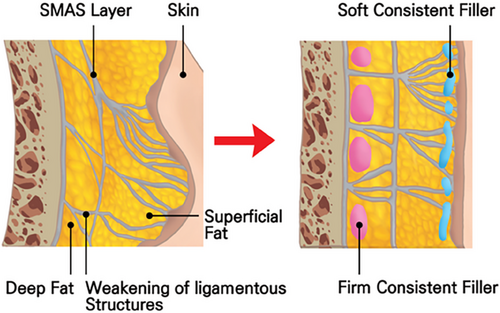

At the core of the SSRT is its emphasis on the anatomical and functional aspects of the midface's SMAS layer, which plays a pivotal role in facial aesthetics.21 Injecting firm fillers beneath the SMAS layer increases the density within this critical area, leading to a cascade of physiological responses. As the filler expands the underlying tissues, the SMAS layer is induced to lift, exerting a tension on the adjacent connective tissues. This tension prompts the surrounding tissues to adapt, stretching and conforming to the new contours, effectively creating a lifting effect that is both natural and aesthetically pleasing (Figure 2).19

The SSRT, pioneered by the author, leverages a nuanced understanding of facial anatomy to achieve natural lifting effects through the strategic placement of firm fillers within the subSMAS space.22 This technique capitalizes on the inherent properties of the SMAS layer, which spans the entire face and integrates closely with both the skin and underlying connective tissues. When firm fillers are introduced beneath this layer, they induce a tightening effect due to their volume and density. This, in turn, exerts a mechanical pulling force on adjacent tissues, thereby fostering a lifting and volumizing outcome.

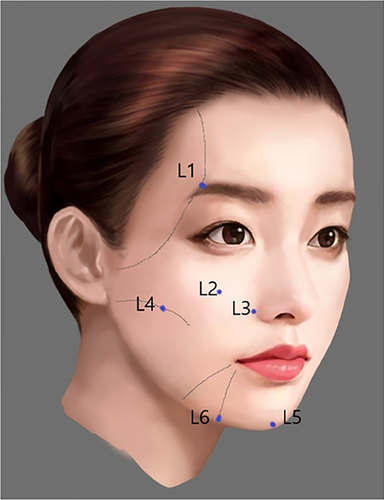

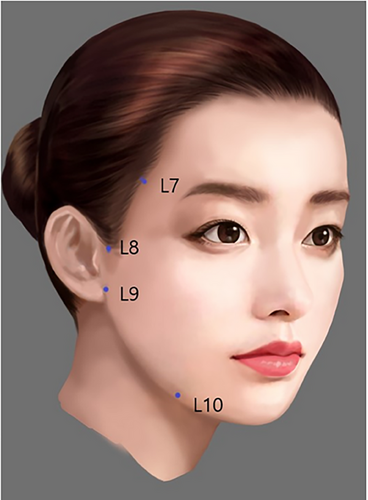

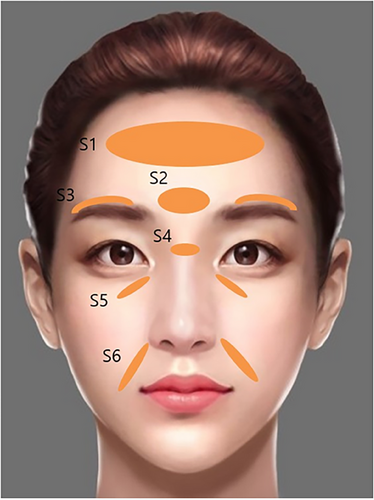

Anatomical variability in the type, thickness, and density of facial areas is crucial in determining the efficacy and direction of this lifting effect.23 The facial structure is a complex interplay of the SMAS layer with both superficial and deep fibroadipose connective tissues, each possessing distinct mechanical properties (Figure 3). By adjusting the viscosity and cohesiveness of the fillers to suit specific facial zones, practitioners can effectively sculpt the face, enhancing both its volume and upward lift.

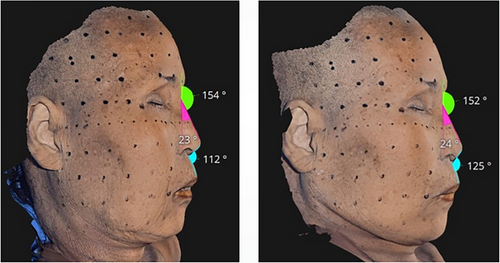

This lifting mechanism is contingent upon the natural tension gradients within the face.24 Areas of slack tissue naturally migrate towards regions where the tissues are firmer, a phenomenon amplified during aesthetic procedures. This migration mimics the gravitational effects observed when the orientation of the face shifts, such as moving from a standing to a lying position, where gravity draws the firmer tissues upward towards the scalp, thus tightening the face. Interestingly, a cadaver study illustrated that, when supine, the areas anterior to the ears and along the jawline exhibit increased tautness and definition, avoiding the accumulation of loose tissues that could otherwise create a bulging appearance along the lower facial contours (Figure 4).25-27

As elucidated in relation to the facial ligamentous structures, numerous robust ligaments are present along the anterior aspects of the ears and jawline. Upon assuming a recumbent position, the more lax tissues surrounding the cheeks and oral region are observed to gravitate uniformly toward these sturdier areas, influenced by the alteration in directional forces and the inherent disparity in tissue robustness. This migration is attributed to the densification of the ligamentous tissues along the ears and jawline under gravitational influence, which results in the tightening of the adjoining skin, thus delineating a more defined jawline and concurrently exerting traction on the adjacent loose cheek and perioral soft tissues. This positional effect of reclining modifies the facial regions characterized by firm ligamentous tissues. Augmentation of these regions with a consistent, firm filler not only resolves the compacted area but also elicits traction on the neighboring skin and SMAS layer.28, 29 Such traction serves to flatten the surrounding lax soft tissues, mimicking an effect of compression. Subsequently, the administration of a soft consistent filler into the dermal and subdermal layers can ameliorate any irregularities or demarcation lines resultant from the initial firm filler injections, additionally mitigating deep wrinkles and fostering a stretching effect in zones with finer wrinkles as depicted in Figure 5.28, 30

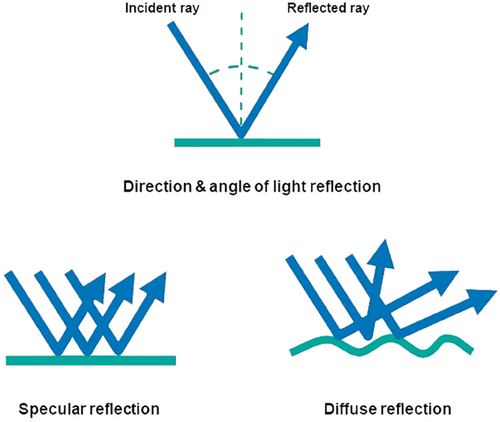

The mechanism by which this smoothing and wrinkle-reducing effect is achieved involves subdermal filling that induces skin stretching, thereby increasing the density of dermal and subdermal tissues. This process results in an indirect blockage at the musculocutaneous junction, effectively smoothing out wrinkles. The technique and plane of soft filler injection beneath the skin are strategically varied to optimize this effect, as illustrated in Figure 6. Additionally, the impact of SSRT treatment in volumizing and refining the skin's surface extends beyond merely altering the face's contour or shape. When one observes an object's surface, the tactile sensation upon contact is integrated with the visual texture perceived, fostering a sensory experience that allows for the mental recreation of the surface texture without direct touch. This enhancement in visual texture is significant. Another critical aspect of visual texture is the degree of light reflection off the surface, which affects our perception of the object's gloss, transparency, depth, thickness, and wrinkling based on the surface structure. For instance, when light strikes the facial skin, it scatters in various directions, yet the incident and reflected rays form specific angles as depicted in Figure 7. A smooth skin surface yields a more uniform reflection angle, reducing shadows and enhancing the visual texture through specular reflection. Conversely, on rough, uneven skin surfaces characterized by large pores or pronounced wrinkles, diffuse reflection predominates, resulting in shadowing and a mottled appearance (Figure 7).30, 31

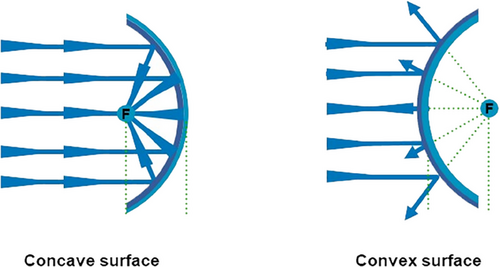

Additionally, light reflection is influenced by the skin's surface contours. If light strikes a concave surface, as depicted on the left side of Figure 8, it reflects inward toward the focus (F), diminishing light scatter and the gloss effect. Conversely, light impacting a convex skin surface, as shown on the right side of Figure 8, scatters outward from the focus (F), enhancing light dispersion and producing a gloss effect, often described as a radiant face. This is a characteristic commonly observed in youthful faces with ample volume and well-defined skin contours, and achieving this effect is a primary goal of SSRT treatment.

When undertaking dual plane filler injections, the viscoelastic properties of the firm filler intended for the subSMAS layer are critical. In regions requiring precise contour maintenance regardless of facial movements, such as the nose, chin tip, jawline, zygomatic central point, and nasal bone depression, a filler with high elasticity should be utilized to avoid shape distortion from surrounding muscle activity and to preserve the original, clear contours.32 Conversely, in areas prone to frequent movement, such as nasolabial folds, corners of the mouth, front cheeks, and perioral cheek regions, using a highly elastic filler may lead to discomfort and unnatural expressions. Thus, a filler with appropriate viscoelasticity and cohesiveness is essential, capable of adapting during movement and reverting to its original form while maintaining a soft, non-angular volume (Figure 9).

For regions requiring accommodation for facial movements, such as the midfacial nasolabial fold area and the lower facial perioral area, the use of a filler with optimal viscoelasticity and cohesiveness is essential for achieving a slimming effect while preserving appropriate volume.33 The cascading impact of this approach on adjacent areas can be substantiated through clinical examples. For example, filler injections in the zygomatic area influence the nasolabial folds, injections in the nasolabial folds impact the upper lip, and injections in the front cheek area alter the appearance of the lower lip.34-37 Similarly, filler placement in the prejowl and lateral cheek areas respectively affect the chin tip and jawline, demonstrating interconnected lifting effects (Figure 10).

In practice, these techniques are often synergistically combined, though SSRT treatments are primarily categorized into three distinct approaches based on their specific objectives. The lifting technique, which employs a minimal amount of very firm filler strategically placed within each facial area, is designed to induce a natural lifting effect. The contouring technique focuses on sculpting an attractive facial silhouette and adding necessary volume. Lastly, the stretching technique involves the subcutaneous injection of soft fillers to effectively tighten the skin and smooth out fine lines and wrinkles, thereby enhancing the overall texture and appearance of the skin (Figures 11 and 12).

The fundamental mechanisms of each SSRT technique merit further exploration. The lifting technique leverages changes in the lifting vector observed when a person lies down, utilizing subSMAS filler injections in areas with robust ligamentous tissues. This densely packs the tissue, pulling adjacent looser tissues upward, thereby creating a natural lifting effect, as illustrated in Figures 11 and 12. Conversely, the contouring technique is inspired by the dynamic volumetric alterations observed in a face when smiling. This method aims to replicate a smiling visage by sculpting facial contours and enhancing key features such as the nose, chin tip, jawline, and zygomatic central point, while filling in recessed areas to even out the facial surface, depicted in Figures 13-15. The stretching technique, shown in Figures 16 and 17, is designed to tighten the skin and mitigate wrinkles by evenly stretching the skin surface, thus enhancing the overall texture and appearance.

The typical facial areas targeted by each technique and the necessary properties and volumes of fillers have been delineated.4 Nonetheless, the selection of fillers during treatment should be predicated on their physical properties and customized to accommodate the individual skin and soft tissue conditions of each patient, as well as their specific aesthetic objectives. This tailored approach ensures that the fillers not only enhance the desired areas effectively but also harmonize with the patient's natural facial dynamics and structural characteristics, optimizing both the visual and functional outcomes of the treatment.

1.2 Myomodulation theory

Dr. De Maio's concept of myomodulation originates from Brazil and posits that manipulating facial expression muscles via filler injections can foster a lifting effect.6, 38 This technique leverages the dynamics between levator muscles, which assist in forming a smile and are thus termed synergists, and depressor muscles, which facilitate frowning and are viewed as antagonists. Dr. De Maio proposes that strategically using HA fillers to adjust muscle activities can significantly enhance facial aesthetics by restoring balance to abnormal muscle movements.

In his comprehensive discourse on myomodulation, Dr. De Maio underscores its importance and elucidates the methodology with three core principles: the Length-tension relationship, the Muscle pulley & lever system, and the Functional muscle group. These principles were thoroughly discussed in his 2018 publication, which clarifies the differential impacts of fillers when administered above versus below the muscles, illustrating the biomechanical foundations of myomodulation in aesthetic medicine.38

1.3 True lift

Taiwanese plastic surgeon Peter Hwang has developed the True Lift method, a technique premised on the notion that facial aging is often characterized by the loosening of supportive ligaments, leading to sagging skin and soft tissues.39 According to this method, strategically injecting fillers beneath these key ligaments can bolster the sagging structures, effectively pulling and lifting the skin to achieve a youthful appearance. This method specifically targets six primary retaining ligaments with firm, consistent fillers: the zygomatic ligaments above the zygomatic arch, the platysma-auricular ligament below the ear lobule, the masseteric-cutaneous ligaments along the anterior boundary of the masseter muscle, the orbital retaining ligament encircling the orbital rim, the maxillary ligament near the nasolabial folds, and the mandibular ligament along the marionette line area of the jawline.

The True Lift shares conceptual similarities with the SSRT by focusing on specific facial ligaments to facilitate a lifting effect. However, Hwang's theory refines the notion that ligament tissues rigidly “stand up” upon filler injection. Instead, it suggests a more nuanced view where the injection of fillers increases the density beneath these ligaments, thus firming the area. This technique is not restricted to the six primary areas; it can be applied wherever strong ligamentous tissues support the skin, potentially producing lifting effects. Effective application of this method relies heavily on a comprehensive anatomical understanding of facial ligamentous structures, ensuring targeted and successful lifting outcomes (as depicted in Figure 18).

1.4 True myomodulation for the latest insights

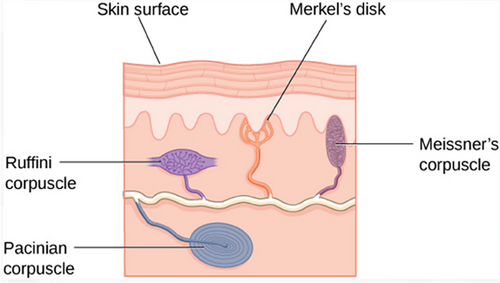

The human face is densely populated with over 17 000 sensory receptors embedded within its musculature, and although the intrinsic sensory system of facial muscles is not fully elucidated, these receptors are broadly categorized into slow adapting (SA) and rapidly adapting (RA) types. Slow adapting receptors primarily transmit signals via the autonomic nervous system (ANS), modulating both sympathetic and parasympathetic responses crucial for facial expressions. They serve a dual function: reducing sympathetic tone and emotional arousal—which dampens activity in the depressor muscles and the frontalis muscle on the forehead—and concurrently activating the elevator muscles, which are involved in parasympathetic responses that foster emotional relaxation.

This nuanced interplay of autonomic responses can precipitate distinct facial movements. Activation of parasympathetic responses typically results in the contraction of elevator muscles around the mouth, eliciting a natural smile, while simultaneously reducing activity in the forehead muscles, which are otherwise engaged during sympathetic excitation. This modulation is mediated by specific mechanoreceptors in the muscles that respond to ANS signals, influencing all facial muscles comprehensively. For instance, strategic filler injections near the cheek muscles can amplify the contraction of elevator muscles, thereby elevating the corners of the mouth. Conversely, placing fillers beneath the depressor anguli oris (DAO) muscle can inhibit depressor muscles, averting the downturn of mouth corners. Similarly, administering injections below the forehead muscles can inhibit their contraction, thereby smoothing forehead wrinkles and enhancing aesthetic outcomes.

Recent immunohistochemical studies have revealed the presence of Ruffini-like corpuscles within the zygomaticus major muscle, akin to those found in the skin.40 This discovery implies that mimetic muscle mechanoreceptors potentially modulate muscle activity in response to filler injections, corroborating the mechanoreceptor filler hypothesis. Should this hypothesis prove accurate, fillers would not only alter facial architecture but also enhance emotional expressions, thereby facilitating genuine myomodulation, as illustrated in Figure 19.41

Moreover, the administration of small particle HA fillers into the dermis significantly boosts skin volume, hydration, and fibroblast activity.42 This, in turn, increases collagen production and antioxidant activities, which enhance skin elasticity and texture. It is posited that stimulating the soft tissue with HA fillers initiates immediate cell contraction followed by tissue remodeling, through the activation and proliferation of fibroblasts. Additionally, employing soft tissue HA volume fillers for facial volumization impacts subcutaneous white adipose tissue (sWAT), activating adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) and promoting the expansion of mature adipocytes.42-44 This results in sustained volumization and tissue firming via hyperplasia and hypertrophy of ADSCs and mature adipocytes, although further research is essential to comprehensively understand these mechanisms.

2 DISCUSSION

In the evolving landscape of facial aesthetics, the SSRT represents a significant advancement in achieving not only volumization but also a natural lifting effect through strategic filler injections. This technique hinges on a precise understanding of the anatomical and dynamic properties of facial soft tissues, particularly how they interact under different expressions and orientations. Traditional approaches often focus solely on filling wrinkles or replacing lost volume, but SSRT aims to mimic the natural lift seen when smiling, using both firm and soft fillers to affect the SMAS layer and underlying structures.

The clinical application of SSRT involves a nuanced use of fillers of varying consistencies—firm for deeper structural support and soft for superficial smoothing—to sculpt a naturally youthful and dynamic appearance. By strategically increasing tissue density beneath the SMAS, the technique leverages the natural tensile properties of facial connective tissues to induce a lifting effect, pulling sagging areas upward and outward, mimicking the effect of facial expressions like smiling. This approach not only enhances facial symmetry and contours but also respects the natural movement, avoiding the stiffness often associated with overfilled faces.

Furthermore, SSRT considers the gravitational effects on facial tissues, providing insights into how facial contours can be optimized by simulating the appearance of lying down, where gravity pulls the tissues differently, suggesting a potential for a transformative ‘lift’ when upright. This concept is visualized through advanced imaging techniques that track the shifting of tissues, offering a compelling visual proof of concept for SSRT's effectiveness.

As we compare SSRT with other globally recognized methods like the True Lift and Myomodulation, it becomes evident that each technique has its merits depending on the specific needs and anatomical considerations of the patient. SSRT, in particular, excels in creating a harmonious balance between volume enhancement and dynamic facial expression, achieving a visibly lifted but natural appearance without the risks associated with excessive filler use.

By integrating SSRT into clinical practice, practitioners can offer a more tailored aesthetic solution that goes beyond traditional filling techniques, addressing the patient's aesthetic concerns with a holistic approach that considers both the static and dynamic aspects of the face. This method not only enhances the immediate visual appeal but also promotes a longer-lasting, natural-looking result, aligning with the modern ideals of subtle and effective cosmetic intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article. This study was conducted in compliance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.