Policy convergence in authoritarian regimes: A comparative analysis of welfare state trajectories in post-Soviet countries

Abstract

enDo authoritarian regimes adopt similar or equal policies? Despite the large literature on policy convergence in democracies, we know little about whether and to what extent authoritarian regimes follow analogous paths. This article argues that similar policy legacy, political and institutional context, and international influences lead to policy convergence among nondemocratic regimes. Analyzing welfare state trajectories in Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan, the empirical analysis finds that the welfare state in the three post-Soviet countries has converged at the level of social spending and the source of welfare financing, while divergence persists in disaggregated levels of social spending; configuration of key welfare programs, particularly in old-age pensions and unemployment; and the extent of welfare state reforms. Overall, the findings provide important insights into the determinants of policy convergence in nondemocratic regimes and yield critical implications for future research on the welfare state's trajectory in former Soviet countries.

Resumen

es¿Los regímenes autoritarios adoptan políticas similares o iguales? A pesar de la abundante literatura sobre la convergencia de políticas en las democracias, sabemos poco sobre si los regímenes autoritarios siguen caminos análogos y en qué medida. Este artículo sostiene que un legado político similar, un contexto político e institucional e influencias internacionales similares conducen a la convergencia de políticas entre regímenes no democráticos. Al analizar las trayectorias del estado de bienestar en Kazajstán, la República Kirguisa y Tayikistán, el análisis empírico encuentra que el estado de bienestar en los tres países postsoviéticos ha convergido en el nivel del gasto social y la fuente de financiación del bienestar, mientras que la divergencia persiste en niveles desagregados. del gasto social; configuración de programas clave de seguridad social, particularmente en pensiones de vejez y desempleo; y el alcance de las reformas del estado de bienestar. En general, los hallazgos proporcionan importantes conocimientos sobre los determinantes de la convergencia de políticas en regímenes no democráticos y generan implicaciones críticas para futuras investigaciones sobre la trayectoria del Estado de bienestar en los países de la ex Unión Soviética.

摘要

zh威权主义政权是否采取类似或平等的政策?尽管有大量关于民主国家政策趋同的文献,但我们对威权主义政权是否以及在多大程度上遵循类似路径一事知之甚少。本文论证,相似的政策遗产、政治和制度情境、以及国际影响,会导致非民主政权中的政策趋同。通过分析哈萨克斯坦、吉尔吉斯共和国和塔吉克斯坦的福利制度轨迹,本实证分析发现,这三个后苏联国家的福利制度在社会支出层面和福利融资来源上趋同,而在以下方面持续存在差异:社会支出的分散程度、主要社会保障计划的配置(特别是养老金和失业方案)、以及福利制度改革的程度。总体而言,这些发现为非民主政权中政策趋同的决定因素提供了重要见解,并对前苏联国家福利制度轨迹的未来研究提供了重要启示。.

INTRODUCTION

Cross-national research on policy convergence has a long tradition in political science (Knill, 2005). The question of whether, how and why countries develop similar or identical policies has captured the attention of many scholars in the field of comparative public policy. The issue assumed particular relevance at the beginning of the 1990s, when the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) left space for capitalist economies to spread, and the logic of a single market in Europe became a central issue in the political debate. Since then, several contributions on this topic have produced important insights into the nature, processes, causes and consequences of policy convergence.

However, at least up until now, the literature has failed to provide substantive evidence of policy convergence outside of the democratic box. While reviewing all major contributions in convergence research, Heichel et al. (2005) find that the bulk of the literature exclusively covers European or Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, while ‘studies that focus on developing or Latin American countries are the exception’ (Heichel et al., 2005, 819). This limited geographical lens of analysis on Western democracies is explained partially by the research industry on Europeanization that has long dominated the field (Knill, 2005). Not until the beginning of the 2000s could one find the first studies on policy convergence in post-communist (e.g., Lavenex, 2002; Orenstein, 2003; Tavits, 2003) and Latin American (e.g., Dobson & Ramlogan, 2002; Murillo, 2002; Serra et al., 2006) countries. However, research outside of the Western bloc since then consistently has remained underdeveloped in comparative terms.

A major consequence is the underrepresentation of authoritarian regimes in this research field. Many European or OECD countries are democracies; thus, nondemocratic regimes have been excluded systematically from analyses. Furthermore, empirically oriented studies are very limited. Most contributions predominantly debate the theoretical foundation and causal factors related to policy convergence. A closer look at the most recent publications in the public policy literature reveals that the debate has drifted toward theoretical underpinnings and mechanisms that lead to policy convergence (e.g., Heichel et al., 2005; Holzinger & Knill, 2005; Knill, 2005), with only limited attention paid to its empirical applicability (e.g., Bouget, 2006; Clegg, 2014; Starke et al., 2008).

The present study aims to address some of these gaps in the literature by investigating whether and to what extent nondemocratic regimes develop similar welfare state trajectories over time. To answer this question, the theoretical argument builds on two assumptions. First, several studies underscore that public policies are significantly different between democracies and autocracies, as both the political context and decision-making process vary extensively (Halperin et al., 2005; Hausken et al., 2004; Mansfield et al., 2000). However, when it comes to social policy and the welfare state, comparative research produces mixed results. Studies based on institutional and voting theories emphasize that the presence of free and fair elections, party competition, and voting behaviors lead to better social policy outputs and outcomes (Acemoglu et al., 2015; Boix, 2003; Meltzer & Richard, 1981). Conversely, most recent contributions reveal that autocracies and democracies do not differ in the total amount of public spending on education or other welfare programs (Mulligan et al., 2004; Schmidt, 2014) as well as in adopting old-age pension programs (e.g., Knutsen & Rasmussen, 2018). In some cases, autocracies might also provide more generous welfare benefits than democracies (e.g., Grünewald, 2021a).

Relatedly, the burgeoning literature on social policy in nondemocratic contexts shows that policy decisions are not immune to internal and external pressures. For a long time, public policy in authoritarian regimes received limited attention due to these governments' hierarchal and top-down decision-making processes, thus policy decisions were equated with autocrat's interest to hold onto power. As Williamson and Magaloni (2020) point out, the basic model of decision-making in nondemocratic regimes is that incumbents choose and implement policies that maximize the likelihood of strengthening their position of power. However, we now have empirical evidence that regime's political and institutional characteristics (De Mesquita et al., 2003; Miller, 2015; Williamson & Magaloni, 2020; Panaro & Vaccaro, 2023) and international organizations (Béland & Orenstein, 2013; Deacon, 2000b; Drezner, 2001) influence social policy decisions and outcomes also in hierarchical context as the one that characterizes authoritarian regimes.

Here, I follow these insights to argue that authoritarian regimes are just as likely as democracies to provide social policy concessions and implement welfare state reforms, and scrutinize the extent to which, given similar policy legacy, political and institutional context, and international influences, we observe welfare state convergence among authoritarian regimes.

Empirically, welfare state convergence is assessed in two steps. First, a descriptive analysis of the trend based on two indicators of policy output – expenditure levels and welfare funding sources – in three social policy fields (health, education and social protection) is conducted to provide a broad picture of the most recent welfare state developments. The analysis then is narrowed down to two institutional features – generosity and inclusiveness – of two welfare programs: old-age pension and unemployment. While historically old-age pensions were at the core of the old Soviet welfare system and nowadays constitute an exemplary form of co-optation in nondemocratic regimes (Knutsen & Rasmussen, 2018), unemployment and labor market reforms rose on the agenda in some of the governments of countries of the former Soviet Union (FSU) over the past decade (Cook & Titterton, 2023; Hofmann, 2018). As such, both old-age pensions and unemployment are of particular interest in the study of the FSU's welfare state trajectory.

A second step in the analysis is the reconstruction of a welfare state trajectory in the three selected countries. In particular, I identify welfare state reforms in the three countries to unveil whether they have been major sustainable reforms or only minor adjustments in the social sphere.

In short, the article provides empirical evidence of a broad welfare state convergence among post-Soviet autocracies, particularly at the level of health and social protection expenditures, and the source of welfare financing. However, divergence remains in the degree of generosity and (partially) in the extent of inclusiveness for two major welfare programs – old-age pension and unemployment. Furthermore, when reconstructing welfare state development and identifying major welfare reforms, variation persists between Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic, on one hand, and Tajikistan, on the other hand.

Overall, the findings are interesting not only with reference to the post-Soviet cases, but also in light of the previous limitations in the policy convergence literature. By using the dynamic notion of policy convergence, the analysis reveals that, similar to democracies, authoritarian regimes face incentives to adopt similar or equal social policy decisions and welfare state reforms. However, the findings also shed lights on the need to combine a political and institutional lens of analysis with a global perspective to scrutinize cross-national welfare state convergence fully.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses the notion of policy convergence, while Section 3 examines major determinants of welfare state convergence. Sections 4 and 5 present the case studies and methodology, respectively. Section 6 provides an empirical assessment of welfare state convergence in the three selected countries during the most recent period. The article concludes with a summary of the results and potential implications of the findings for further research on policy convergence in nondemocratic contexts.

DEFINING POLICY CONVERGENCE AS A DYNAMIC PROCESS

The convergence literature offers myriad definitions of policy convergence and related concepts (Heichel et al., 2005). In general terms, policy convergence is equated with ‘any increase in the similarity between one or more characteristics of a certain policy, across a given set of political jurisdictions and over a given period of time’ (Knill, 2005, 768). Building on this definition, few distinctive features characterize policy convergence.

First, policy convergence applies to one or more characteristics of a certain policy. Thus, studies on policy convergence deal with distinct policy areas (e.g., social policy, environmental policy, fiscal policy, trade policy, monetary policy, etc.) and in some cases also might yield different results based on the characteristics of the policy under investigation. For example, the research on social policy convergence in the European Union (EU) provides contrasting evidence on whether there has been a common trend in welfare state trajectories among EU countries. Some scholars have embraced the convergence hypothesis (Bouget, 2003, 2006; Casey, 2004; Greve, 1996), while others have demonstrated that divergence persists (Graziano, 2012; Jessoula et al., 2014; Palier et al., 2018). This apparent contradiction on social policy convergence in the EU depends on the specific policy field (e.g., healthcare, education, pension, or labor market regulations) and distinct aspects of the public policy under scrutiny (e.g., schemes' institutional features, output indicators, or outcomes). As such, the policy dimension(s) and its characteristics under investigation should be identified clearly at the outset.

Second, policy convergence is a process that should be conceptualized in a dynamic term rather than a static objective to be reached. As Bennett (1991) argues, ‘convergence implies a pattern of development over time’ (219). Thus, the temporal dimension and the dynamics toward similar or identical policies comprise policy convergence's theoretical underpinning.

Interestingly, some scholars have posited that policy convergence also can be understood as the result of an increasing trend in policy similarities across countries, while other related concepts capture processes that lead to convergence, e.g., policy diffusion and policy transfer (Knill, 2005). However, this argument hinges on a major problem. These scholars conceive policy convergence as a static objective, with no attention devoted to the policy characteristic(s) compared. For instance, two or more countries might adopt similar policy instruments in the provision of healthcare services, but still diverge on the policy content in the respective field. In this case, the result is the similarity in policy instruments, while divergence remains in the process through which two or more countries come together. Along these lines, if it is true that the public policy literature offers other concepts ‘to describe mechanisms that lead to policy similarities’ (Knill, 2005, 767), then policy convergence more strictly entails a pathway to similar or identical policies. According to Inkeles (1999), ‘convergence means moving from different positions toward some common point. To know that countries are alike tells us nothing about convergence. There must be a movement over time toward some identified common point’ (Inkeles, 1999, 13–14). Building on this theoretical reasoning, policy convergence is understood here as a temporal dynamic process that leads to a common point.

NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL LOGIC OF WELFARE STATE CONVERGENCE

The research on convergence has a long history in the literature on comparative welfare state. Between the 1950s and 1970s, structural-functionalist theories explained welfare state expansion in Western democracies during the post-Cold War period by stressing socioeconomic conditions as key drivers of welfare state convergence (Kerr, 1960; Wilensky, 1975). According to functionalist theories, a common industrialization process has created similar needs in modern nations, leading to adoption of analogous social policy responses. However, when it comes to recent systemic pressures, such as post-1973 economic stagnation, labor market transformations, technological changes and increasing capital and trade flows, on welfare state development, empirical research produces mixed results (Bonoli, 2005; Garrett, 2001; Genschel, 2004). In particular, several scholars cast doubt on the direct link between socio-economic transformations and welfare state development, suggesting that welfare institutions are ‘sticky’ and do not adapt quickly to different socioeconomic contexts (Pierson, 2001). More generally, empirical evidence suggests that socioeconomic conditions do not constrain states from making autonomous policy choices (Drezner, 2001; Mosley, 2005).

In reviewing major contributions in the comparative welfare state research, I pinpoint three factors accounting for welfare state convergence in nondemocratic regimes: policy legacy, political and institutional context, and the role of international organizations.

Since the 1980s, historical institutionalist scholars interested in social policy reform and welfare state development have acknowledged that welfare trajectories are conditioned predominantly by previous enacted policymaking measures, so-called policy legacies. These reflect policy decisions and recommendations that policymakers, government officials and social policy experts formulate and transmit from one government to another (see Pierson, 2001). Accordingly, policy legacies favor reproduction of institutional logics and welfare interests, leading toward so-called path-dependence in welfare state development (Mahon, 2000; Pierson, 2000). Some studies push this argument even further by demonstrating that colonial heritage leads toward channeled paths of welfare state adjustments. For example, Schmitt et al. (2020) find that the legacies of colonialism and communism play an important role in accounting for cross-national differences in social protection financing patterns. In the case of nondemocratic regimes, the colonial heritage is of utter importance if studying welfare state development as most of them are developing countries with a colonial history and have introduced first social protection programs before they gained independence (Schmitt, 2015, 2020). Hence, autocracies that have a common policy legacy would see their welfare state ‘locked in’ on a similar developmental path.

Admittedly, various strands of the new institutionalism school highlight political institutions' significant impact on welfare state adjustment. There is a long tradition in the literature on institutionalism that indicates the impact of regime type on social policy decisions and the welfare state. Those studies underscore that democracies have more generous and inclusive welfare systems than authoritarian regimes (e.g., Brown & Hunter, 1999; Lake & Baum, 2001; Rodrik & Wacziarg, 2005). In general terms, the so-called ‘democracy advantage’ hypothesis (Halperin et al., 2005) posits that the presence of electoral competition, broader enfranchisement, universal suffrage and political and civil rights favor adoption of a more inclusive welfare system. For all theories maintaining that democracy matters, social policies are expected to converge, given similar political and institutional conditions (e.g., Pierson, 2001; Skocpol & Amenta, 1986).

When looking more specifically at authoritarian regimes, previous studies show that differences in political and institutional context determine varied incentives for autocrats to provide social policy concessions (Gandhi, 2008; Knutsen & Rasmussen, 2018; Panaro & Vaccaro, 2023). In electoral autocracies, where incumbents seize power through elections and establish legislatures to consolidate their hold on power, social policy concessions tend to be more generous than closed autocracies, where leaders gain power through military coups and govern with extensive use of repression. Moreover, empirical evidence suggests that policy-making process is different between electoral and closed regime types. Incumbents in electoral autocracies face more incentives to collect information; thus, non-state actors have more opportunities to enter the political arena and potentially influence policy decisions than in closed autocracies (Guriev & Treisman, 2020; Panaro, 2023). If we push this argument further, given similar political and institutional setting, we should expect authoritarian regimes to develop similar welfare systems.

Finally, while policy legacy and political arena are factors in determining welfare state trajectories, the international context also might influence national social policy decisions. Global social policy scholars are attuned to the role of international organizations in facilitating adoption of similar welfare programs and common social security legislation through the diffusion of ideas, recommendations and measures (Deacon, 2000a; Deacon & Stubbs, 2013). For instance, Obinger and Schmitt (2022) find that the International Labour Organisation's (ILO) activities impinged on the introduction of unemployment insurance in the Global South, while Martens et al. (2021) demonstrate extensively how international organizations shape national social policy through implementation, financing and diffusion of projects in their member states. In a nutshell, when it comes to welfare state provision and adoption of social protection programs, several studies show that international organizations play a major role in influencing welfare state development in the Global South (e.g., Abu Sharkh & Gough, 2010; Deacon, 2000b; Isabekova & Pleines, 2021; Obinger & Schmitt, 2022).

CASE SELECTION

To test the validity of proposed theoretical arguments, I studied welfare state development in three post-Soviet autocracies in Central Asia – Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan – between 2000 and 2019. Case selection was based on the so-called most-similar case design, in which cases are chosen based on one or more specified dimensions of interest (Elman et al., 2016; Seawright & Gerring, 2008). The cases are similar in terms of all potential explanatory factors of welfare state convergence.

First, all three selected countries inherited the Soviet welfare state, in which the state played a central role, providing generous and extensive welfare benefits (Madison, 1964; Manning, 1984). More recently, empirical research indicates that welfare responses across FSU countries during the late 1990s and early 2000s were largely similar. According to Deacon (2000b), all post-communist and post-Soviet countries borrowed practices from Western economies and implemented the so-called ‘post-communist welfare package’. Policy reforms principally included scaling back unemployment benefits; lowering wages; replacing state subsidies for food, housing, transport and basic necessities with means-tested subsidies; reducing child-care benefits and services; implementing health insurance schemes and service fees and, more broadly, replacing universalistic welfare provisions with targeted welfare programs. While attempting to fit post-communist countries' welfare systems into Esping-Andersen's (1990) typology, Deacon and Standing (1993) push this argument even further by identifying a new ‘post-communist conservative corporativist’ welfare regime. A similar conclusion is shared by other scholars, who cluster post-communist or post-Soviet countries into one single welfare regime type. For example, Orenstein (2008a) delineates the key characteristics of a ‘post-communist welfare state’, while Aidukaite (2004) introduces the concept of ‘post-Socialist welfare state’.

However, some scholars dispute the uniformity of a post-Soviet welfare state. They show that sociocultural and economic differences across post-Soviet countries have played a major rule in steering welfare state development, particularly in education (Malinovskiy & Shibanova, 2023) and health policy (McKee et al., 2002). Yet recent welfare state transformations cannot be disentangled from the Soviet legacy. For instance, Orenstein (2008a) argues that citizens in post-communist countries still expect the state to provide social goods. Thus, for all scholars who argue that the communist policy legacy matters (e.g.,Schmitt et al., 2020), policy reforms in these countries is presumed to converge toward a similar welfare state model.

Second, all three selected countries have similar political and institutional settings, as they moved from one type of dictatorship – totalitarianism – to another – electoral autocracy. In some cases, their political leaders were linked to the old Soviet regime as members of the former Communist Party. For example, Presidents Nursultan Nazarbayev and Emomali Rahmon were members of the Soviet Communist Party when they became the first presidents of Kazakhstan and Tajikistan in 1991 and 1994, respectively. Interestingly, despite the outbreak of the Tulip Revolution in 2005 and the People's April Revolution in 2010 in the Kyrgyz Republic, the country has never experienced a transition to either full or flawed democracy (see Economist Intelligence Unit, 2023). As such, all three selected countries have been classified as electoral autocracies since their independence (see Table 1).

| Countries | Electoral autocracy |

|---|---|

| Kazakhstan | 2000–2019 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 2000–2019 |

| Tajikistan | 2000–2019 |

- Source: Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) – Regimes of the World (RoW) (2023).

Furthermore, similar to other countries in Central Asia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan are decentralized institutionally, as their administrative systems are fragmented into four levels: central state; region/oblast; city/rayon; and rural or local communities. For example, Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic have 17 and seven regions (oblasts), respectively, while Tajikistan has three regions (oblasts), the capital city of Dushanbe and 13 districts (rayons) directly subordinate to the central government. This administrative division also is reflected in the allocation of responsibilities in the provision of social benefits and services between ministers and state entities at the national, regional and district levels. For example, in some areas of the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, delivery of welfare services and social benefits sometimes is attributed to local-level community structures, so-called mahallas, which have a strong historical tradition in Central Asia, and their community structure is based on family ties, shared values and solidarity (Rechel et al., 2012; Roche, 2017).

Finally, all three selected countries are members of the same regional and international organizations, which have supported several projects in these countries. For example, they are full members of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) – a regional intergovernmental organization formed after the Soviet Union's collapse in 1991 to facilitate the exchange of goods, services, labor and capital between member states, as well as promote collaboration on security matters – and the ILO, a United Nations agency that promotes social and economic justice, as well as better labor standards and working conditions. Starting in the mid-2000s, the World Bank also enhanced its engagement in Central Asia, promoting a series of projects, e.g., the Migration and Remittances Peer-Assisted Learning (MiRPAL) and Central Asia Regional One Health (CAR/OH) projects, to improve living conditions, promote economic growth, ensure social development and enhance dialogue on health and migration policies.1 Furthermore, since the mid-2000s, the European Union has been involved in a series of initiatives in Central Asia, and in 2007, the EU launched its ‘Strategy on Central Asia’, promoting human rights and good governance, sustainable transport connections, economic diversification and improved social equality, labor conditions and administrative accountability and efficiency in all Central Asian countries.2 Table 2 presents the number of projects in the social sphere that the World Bank and ILO promoted in the three countries from 2000 to 2019. As we can see, the number of projects in health, education and social protection endorsed by both international organizations increased in all three countries during the selected period, leading to international organizations' greater involvement in these nations' social policy strategies. This evidence is also supported by several contributions that show greater involvement of transnational actors in Central Asian countries since mid-1990s, providing policy ideas and technical assistance to welfare reforms (Deacon & Hulse, 1997; Isabekova & Pleines, 2021; Orenstein, 2008b).

| World Bank | International Labour Organization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2009 | 2010–2019 | 2000–2009 | 2014–2019 | |

| Kazakhstan | 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 12 | 22 | 0 | 3 |

| Tajikistan | 13 | 21 | 0 | 2 |

- Source: World Bank Project and ILO Programs and Projects Dataset.

Overall, this section reveals that all three examined authoritarian regimes inherited the communist legacy on social policy and adopted similar welfare state responses, developed a similar institutional and political context and were exposed to equal international pressures. Thus, based on theoretical assumptions, it is reasonable to expect welfare state convergence across these countries.

METHODOLOGY

A central issue in empirical studies on social policy is whether to analyze convergence linked to policy outputs, i.e., types of policy that a government adopts, or policy outcomes, i.e., actual policy effects in terms of welfare goal achievement. To examine this choice, I follow Holzinger and Knill (2005), who argue that ‘while policy outcomes are influenced by a myriad of factors which do not necessarily (reflect) governments’ intention, governmental programs are what really count’ (776). This is particularly true in the case of authoritarian regimes in which governmental programs, particularly social spending and decisions on benefit levels, reflect autocrats' interest in distributing resources to targeted groups (De Mesquita et al., 2003).

Following this logic, the empirical analysis primarily rests on policy outputs and welfare reforms. In particular, I employ a mixed-methods sequential explanatory design, which entails first collecting and analyzing quantitative data, then qualitative data, in two consecutive phases (Creswell, 2005, 2008). First, a quantitative descriptive analysis is conducted on a set of indicators of policy outputs – government expenditure level and funding source – and institutional features – benefit levels and coverage – from two welfare programs: old-age pensions and unemployment. These two programs were selected for three reasons. First, social protection in the Central Asian countries comprises the bulk of financial resources, compared with health and education (see Table 4).3 Second, old-age pensions historically were at the core of the old Soviet welfare system (see Madison, 1964), while labor market reforms were higher on many FSU countries' agendas (see Lehmann & Muravyev, 2012). Third, recent studies have found that social security programs, and more specifically old-age pensions, are of particular interest in authoritarian regimes (Grünewald, 2021a, 2021b; Knutsen & Rasmussen, 2018). The comparative descriptive analysis of trends on the level of public social expenditures and funding sources among countries and across distinct policy areas allows for identifying whether the welfare state has been expanded or retrenched. Furthermore, by examining the range – as a measure of dispersion – welfare state development is assessed as to whether it has followed a convergence path.

In the second part of the analysis, I identify major welfare reforms in the three policy areas: health; education and social protection. In doing so, I study whether major and substantial reforms or only minor adjustments have been made to the welfare state. To reconstruct welfare trajectories and identify welfare reforms, I rely on international dataset (WB, IMF and ADB), national and international reports, secondary literature and national policy documents.

The descriptive quantitative analysis of trends in policy outputs and the reconstruction of welfare state development in the selected countries is consistent with the theoretical definition of policy convergence as a dynamic process toward a similar or identical policy.

EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

Cross-national comparison in welfare effort

Government social expenditures

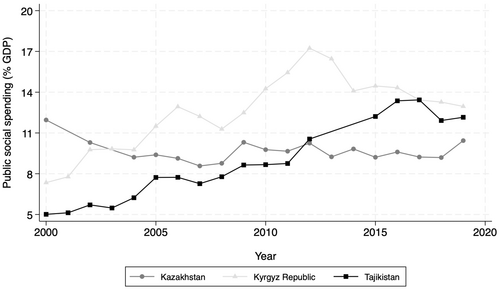

Figure 1 presents data on public expenditures on health, education and social protection as a percentage of GDP and illustrates social spending trends. In Tajikistan, public social spending increased from 5% to 12% of GDP between 2000 and 2019. A similar trend is visible in the case of the Kyrgyz Republic, with an increase in spending from 7% to 16% of GDP between 2000 and 2012, followed by a slow decline to 13% of GDP in 2019. Interestingly, although being the highest spender in 2000, public social expenditures in the case of Kazakhstan do not indicate much variation during the entire period under investigation, as they constantly ranged between 9% and 12% of GDP.

Notably, when examining cross-countries variation, Table 3 indicates a converging trend in social spending across the three countries. As we can see, the range – the difference between the highest and lowest spending levels – decreased from 7% of GDP in 2000 to 2.6% of GDP in 2019. Kazakhstan was the highest spender in 2000 and experienced a modest reduction in public social spending until 2019 (−1.6% of GDP). Conversely, the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan were the lowest spenders, having experienced an increasing trend in social spending of +5.7% and 7.2% of GDP, respectively.

| Country | Total social spending (as a percentage of GDP) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | |

| Kazakhstan | 12 | 9.4 | 9.8 | 10.4 | −1.6 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 7.3 | 11.5 | 14.3 | 13 | 5.7 |

| Tajikistan | 5 | 7.7 | 8.7 | 12.2 | 7.2 |

| Mean | 8.1 | 9.5 | 10.9 | 11.9 | |

| Range | 7 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 2.6 | |

- Source: Data on health and education from World Development Indicators (2023). Data on social protection from Asian Development Bank – Social Protection Indicators Dataset (2023).

Government expenditures on health, education and social protection

Health

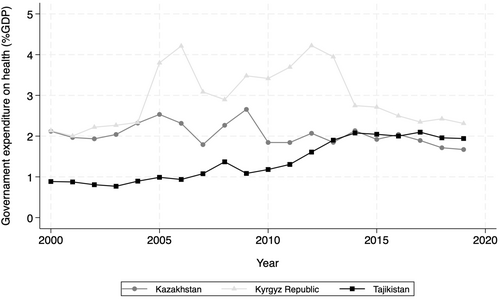

If we examine trends in public health expenditures, we see that the levels followed a different path through the 2000s. Figure 2 reveals that government expenditures on health increased in Tajikistan between 2009 and 2014, and have remained relatively stable since then, whereas Kazakhstan kept its levels quite stable – around 2% of GDP – throughout the period under investigation. However, government expenditures on health in the Kyrgyz Republic reveal a U-shaped pattern: increasing between 2004 and 2006 to 4.2% of GDP, falling in 2007–2008, then increasing again between 2009 and 2012 (4.2% of GDP) and eventually declining thereafter. Interestingly, these sharp increases in health expenditures occurred simultaneously with two major events in the country – The Tulip Revolution (March–April 2005) and the People's April Revolution (April–December 2010) – suggesting that these peaks in health expenditures might be a consequence of internal turmoil.

Despite distinct trends, Figure 2 also reveals that starting in 2014, the three countries have been converging to similar health expenditure levels. As we can see, government health expenditures are quite similar in all three countries between 2014 and 2019.

Education

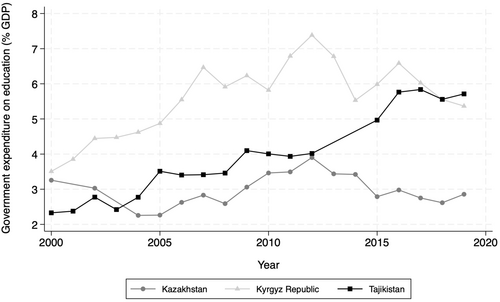

Figure 3 presents trends in government expenditures on education, and a common trend can be spotted quickly with the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan. Both countries increased education expenditures between 2000 and 2012, but while the former experienced a drop between 2012–2014 and again in 2016–2019, the latter reported relatively stable health expenditure levels since 2015. As for Kazakhstan, the trend is different. Figure 3 reveals that government education expenditures in Kazakhstan remained relatively low throughout the period under investigation, with an increase from 2.6% of GDP to almost 4% of GDP between 2008 and 2012. However, since 2015, education expenditures in the country returned to 2000s levels. This trend confirms previous evidence. According to Anderson and Heyneman (2005) and Klugman (1999), not only public, but also private education expenditures in Kazakhstan have remained significantly lower than those of other Central Asian countries since it became independent.

Social protection

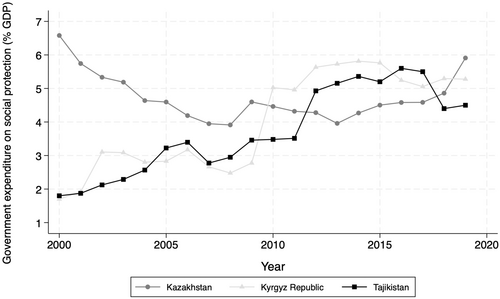

Interestingly, when examining trends in government expenditures in social protection, we notice once again a similar pattern in the case of the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, but not in the case of Kazakhstan. Figure 4 reveals that social protection expenditure levels in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan were identical in 2000 and that the two countries followed a similar expansionary trend throughout the 2000s. However, in 2018, Tajikistan drastically reduced its social expenditure levels compared with the Kyrgyz Republic, which maintained a higher commitment in this social policy field. Conversely, Kazakhstan experienced a completely different U-shaped trend. While reporting a high level of social protection expenditures in 2000 (6.6% of GDP), the government drastically reduced its welfare commitments in social protection, down to 4% of GDP in 2008. However, as Figure 4 reveals, in 2014, the government started increasing public spending again in this sector up to almost 6% of GDP in 2019.

Table 4 reports disaggregated quinquennial levels of social expenditures and the changes between 2000 and 2019 levels in the three countries. When examining within-country variation, Table 4 reveals that while both the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan have experienced an expansionary trend in all three sectors since 2000, Kazakhstan suffered from an inverse trend, as total government expenditures in health, education and social protection decreased until 2019.

| Country | Health | Education | Social protection | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | |

| Kazakhstan | 2.1 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.7 | −0.4 | 3.3 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 2.9 | −0.4 | 6.6 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 5.9 | −0.7 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 2.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.8 | 5 | 5.3 | 3.6 |

| Tajikistan | 0.9 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 4 | 5.7 | 3.4 | 1.8 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 2.7 |

| Mean | 1.7 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2 | 3 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 5.2 | |||

| Range | 1.2 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4 | |||

- Source: Data on health and education from World Development Indicators (2023); Data on social protection from Asian Development Bank – Social Protection Indicators Dataset (2023).

However, these trends parallel a cross-countries variation that reveals a converging pattern in two policy areas. The range in social protection expenditures decreased, moving from 4.9% of GDP in 2000 to 1.4% of GDP in 2019, suggesting a catch-up process in this field. Similarly, the range in health policy increased between 2000 (1.2% of GDP) and 2005 (2.8% of GDP) and decreased since mid-2010, suggesting a converging trend during the most recent period. These data are in line with trends reported in Figure 2, revealing parallel health expenditure levels for the three countries starting in 2014. Conversely, no converging trend surfaced in the education sector, as cross-country variation remained considerably high. As we have seen, while public education expenditures increased in both the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, public spending on education remained very low in Kazakhstan.

Overall, the empirical analysis reveals a broad converging trend in total social spending, mostly driven by a catch-up process in government expenditures on social protection and health, starting in 2014. However, education expenditure levels remained largely different across the three countries.

Welfare state funding

During the transition phase, many of the FSU countries moved from a state-centric approach, in which all social services were financed through general taxation, toward the establishment of an occupational welfare, in which social benefits and services are financed through social contributions paid by employers and/or employees. However, Table 5 presents data from an inverse trend occurring in the past two decades. Despite a general increase in the level of social security contributions, from 0.5% of GDP in 2000 to 2.7% of GDP in 2019, state taxes remain the main source of welfare funding in all three countries. The average level of total contributions as a percentage of GDP increased from 14.2% to 18.3% of GDP from 2000 to 2019.

| Country | Total taxation (as a percentage of GDP) | Social security contributions (as a percentage of GDP) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | |

| Kazakhstan | 20.2 | 20.2 | 19.6 | 15.1 | −5.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 11.7 | 14.9 | 17.5 | 19.4 | 7.7 | 0 | 0 | 5.5a | 5.2 | 5.2 |

| Tajikistan | 10.7 | 12.8b | 18 | 20.5 | 9.8 | 1.6 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 2.4c | 0.8 |

| Mean | 14.2 | 16 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 0.5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 | ||

| Range | 9.5 | 7.4 | 2.1 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.7 | ||

- Note: For Tajikistan, author's calculation based on total social security contributions in national currency and total level of GDP. Source: ILO World Social Protection Data Dashboards (2023); IMF Government Finance Statistics; World Bank national account data.

- a 2014.

- b 2003.

- c 2016.

When examining welfare funding trends within countries, both total taxation and social contributions increased in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, with total taxation growing by 7.7% of GDP and 9.8% of GDP, and social contributions increasing by 5.2% of GDP and 0.8% of GDP, respectively. However, Kazakhstan experienced a shift toward an occupational welfare system. The total taxation level actually decreased (−5.1% of GDP), while the number of social contributions as a new source of welfare funding increased slightly (+0.5% of GDP).

To determine whether a convergence process occurred, Table 5 reports a descriptive analysis of cross-countries variation in welfare funding. As can be seen, the range in total taxation declined between 2000 (9.5%) and 2019 (5.4%), suggesting a converging trend in state taxes as a source of welfare funding. However, variation in social security contributions expanded as the range in social security contributions increased from 1.6% of GDP in 2000 to 4.7% of GDP in 2019.

So far, the analysis of policy output indicators has produced a broad picture of welfare state convergence in the three countries. However, it still does not tell us much about welfare program characteristics. According to Starke et al. (2008), social expenditures are insufficient to assess whether policy convergence or divergence in welfare state development has occurred. Following this logic, the analysis of policy outputs is complemented with a more fine-grained study on welfare programs' institutional characteristics. The next two sections untangle the generosity and coverage of two social security programs: old-age pension and unemployment. As previously discussed, these two programs are highly significant in post-Soviet countries due to their historical legacy and current rule as major caseloads of social expenditures.

Degree of generosity

Table 6 presents the benefit levels for old-age pension4 and unemployment,5 expressed in dollars per month. On average, the benefit amount for the two welfare programs increased since 2002 in all three countries. Kazakhstan experienced the highest increase in both old-age (+$58.70/month) and unemployment benefits (+$50.90/month). The increase in old-age pension benefits has been more moderate in both Tajikistan (+$3.50/month) and the Kyrgyz Republic (+$12.60/month). This pension trend is quite interesting because, as previous empirical research has demonstrated (Cook, 2000; Falkingham & Vlachantoni, 2010, 2013; Grishchenko, 2016; Rajabov, 2016), during the transition period, FSU countries moved toward different pensions models, including pay-as-you-go (PAYG) (e.g., Tajikistan) and fully funded (e.g., Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic) systems. However, Table 6 clearly reveals that despite distinct pension models, since 2002, there has been an increasing trend in the degree of generosity in old-age pensions. Similarly, unemployment benefits increased in Kazakhstan (+$50.90/month), the Kyrgyz Republic (+$2.10/month) and Tajikistan (+$38.10/month).

| Country | Old-age pension | Unemployment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2019 | Change (2002–2019) | 2002 | 2019 | Change (2002–2019) | |

| Kazakhstan | 28.3 | 87 | 58.7 | 19.9 | 70.8 | 50.9 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 2.1 | 14.7 | 12.6 | 1.6 | 3.7 | 2.1 |

| Tajikistan | 8.4 | 11.9 | 3.5 | 5.9a | 44 | 38.1 |

| Mean | 12.9 | 37.9 | 9.1 | 39.5 | ||

| Range | 26.2 | 75.1 | 18.3 | 67.1 | ||

- Note: All values are expressed as U.S. dollars per month; Old-age and unemployment benefits refer to the minimum old-age pension and unemployment cash benefit per capita.

- Source: ISSA Dataset (2018) and ILO Statistics (2023).

- a 2010.

However, despite a general increase, Table 6 indicates no convergence across the three countries, as both old-age pension and unemployment benefit ranges have been consistent between 2002 and 2019.

Extent of inclusiveness

As a final dimension of welfare state change, Table 7 reveals the extent of the coverage for the same two welfare programs. As we can see, old-age pension coverage increased in both the Kyrgyz Republic (+14%) and Tajikistan (+12%), while it decreased slightly in the case of Kazakhstan (−0.4%). This evidence suggests that while old-age pension programs have been extended to cover a broader share of the population in the case of the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan, there have been smaller cuts in Kazakhstan.

| Country | Old-age pension | Unemployment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | 2000 | 2019 | Change (2000–2019) | |

| Kazakhstan | 100 | 99.6a | −0.4 | 0.5 | 5.8a | 5.3 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 86 | 100 | 14 | 8.2 | 1.7a | −6.5 |

| Tajikistan | 88b | 100 | 12 | 5.1b | 17.3a | 12.2 |

| Mean | 91.3 | 99.9 | 4.6 | 8.3 | ||

| Range | 14 | 0.4 | 7.7 | 15.6 | ||

- Note: Old-age pension coverage refers to the percentage of individuals above the retirement age receiving a pension. Unemployment coverage refers to the percentage of unemployed receiving unemployment benefits.

- Source: ILO Statistics (2023).

- a 2016.

- b 2005.

As for the extent of unemployment coverage, the trend is different. Coverage for unemployment benefits increased in Kazakhstan (+5.3%) and Tajikistan (+12.2%), but decreased for the Kyrgyz Republic (−6.5%), suggesting a markedly different pattern.

Overall, Table 7 reveals that despite distinct pension schemes, FSU countries either maintained (Kazakhstan) or adopted (the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan) a more inclusive approach in the field of old-age pensions. This convergence trend is confirmed by a decrease in the range between 2000 and 2019. Conversely, this approach has not been pursued in the case of unemployment. Cross-countries variation increased drastically during the 2000s as the range in the percentage of the population covered by unemployment programs increased from 7.7% in 2000 to 15.6% in 2019. These results indicate that the diversity in the inclusiveness of unemployment programs remains notable.

Major welfare state reforms

Kazakhstan

Among all Central Asian countries, Kazakhstan was the fastest to implement neoliberal market reforms in the social sphere and the first country among FSU states to introduce defined contribution policy and private pension funds (Rajabov, 2016). In 1996, the Kazakhstani government introduced a compulsory and universal health insurance system and replaced the inherited PAYG scheme with one based entirely on fully funded individual accounts. However, major difficulties in the collection of taxes and social contributions, combined with the country's economic fluctuations, seriously impaired the financial sustainability of the country's welfare system, thereby pushing the government to change its strategy. As addressed in the 1997 President's Strategy for Kazakhstan 2030, private investments in healthcare and education became a priority for the government. In 1998, the government abandoned the fully funded healthcare system by encouraging private investments in health services and provisions, particularly in rural parts of the country, and incentivized creation of the first private pension funds. Initially, most Kazakhs opted for the state pension fund, which was viewed as more reliable, but the share of monthly contribution receipts to private pension funds sharply increased between 1998 and 2001, from 20% to 70% (Buribayev et al., 2016).

Following this approach, a series of neoliberal reforms on the governance and finance of healthcare, education and pension sectors was introduced in 2000. First, the Ministry of Education and Science proposed a privatization process, according to which, a select group of existing public universities would be transformed into joint-stock companies in which private investors held 35% of the share, with the government holding the rest (Hartley et al., 2016). These institutions were granted major institutional autonomy in admission guidelines, curriculum design and budget allocations. Second, in 2004, the Ministry of Healthcare launched the National Programme for Healthcare Reform and Development, which set out general guidelines to improve the healthcare system between 2005 and 2010. It underscored the need to improve health services' quality and efficiency, create a new regulatory framework, ensure equitable access to health services and shift toward primary and outpatient care (Amagoh, 2021). More importantly, these reforms represented a turning point in the development of the healthcare system because they created a new healthcare management mode in which responsibility for healthcare shifted from the state to the individual level (Aizhan & Saipinov, 2014). Third, in July 2004, a new law deregulated governance of pension funds, allowing them to invest in foreign government securities and foreign mutual fund assets, i.e., they were allowed to invest in large domestic infrastructure projects and use foreign asset management companies. Pension funds also could invest up to 20% of their funds in domestic mortgage securities and 15% in commercial banks (Lim, 2005).

However, during the 2010s, there was a reversal in the government strategy to bring the state back into the healthcare and pension sectors. With President Nazarbayev's ambition to make Kazakhstan one of the world's 50 most competitive countries by 2015, the Ministry for Health established the Unified National Health System in 2011 and adopted the State Policy for Public Health 2016–2019, which emphasized the need to develop a modern and financially sustainable national health system focussing on training and education of healthcare workers (Amagoh, 2021). Simultaneously, the government reduced the room for maneuver to private pension funds and eventually introduced a new reform in 2013 that united all private pension funds into one single fund managed by National State Bank (Grishchenko, 2016). However, the government continued to pursue a privatization strategy in education policy. Several education reforms were implemented to increase the Kazakhstani education system's international relevance and competitiveness, and align it with international standards. Notably, most reforms aimed to attract private investments in education to improve teaching quality, attract international students and invest in new methodologies (e.g., distance learning, online lectures and web-hosted lectures) (Massyrova et al., 2015). As a result, the number of private higher education institutions and universities compared with public institutions increased sharply, and the state continues to be only a marginal provider of education services (Anderson & Heyneman, 2005; Hartley et al., 2016).

The Kyrgyz Republic

The trajectory of welfare state development in the Kyrgyz Republic has been influenced largely by the Soviet policy's legacy. Between 1991 and 1996, the state continued to provide generous social insurance benefits, particularly in old-age pensions (IMF, 2000). However, during the transition phase, the old welfare state commitments became unsustainable due to the country's economic instability, lack of resources, increasing inflation, collapse in employment levels and worsening social outcomes (IMF, 2000). In 1997, the government introduced the Pension Law, which converted the PAYG system to a notational defined contribution (NDC) system (Bogomolova, 2014). Simultaneously, the government restructured its healthcare system, which made the country among the first FSU countries to introduce a mandatory health insurance scheme (Heinrich et al., 2022). With the National Health Care program Manas (1996–2005), then the National Health Care program Manas Taalimi (2006–2011), the government strengthened the state healthcare system, restructured healthcare delivery, introduced a family medicine institute and a mandatory health insurance system for all citizens, and implemented progressive social contributions. Importantly, several studies confirm that both programs were successfully implemented only thank to the financial and technical support of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Bank (Isabekova & Pleines, 2021; Ministry of Health, 2006; WHO, 1997).

By 2010, major structural welfare state reforms in the field of social protection also were adopted. The newly established government officially included a fully funded component in the pension system, increased benefit levels in existing social protection programs and introduced in-cash benefits for certain ‘privileged population groups’. As the OECD (2018) reported, before 2010, the Kyrgyz social protection system – administered by Parliament, the Ministry of Health and local communities – was heavily fragmented, regulated under more than 10 laws while providing 40 distinct types of privileges to 39 categories of beneficiaries. These privileges included price discounts on housing, health services, utilities and other municipal services (Bogomolova, 2014). Meanwhile, funding for social assistance and social services for vulnerable groups remained limited and mostly directed toward supporting residential institutions for children, people with disabilities and the elderly.

Against this backdrop, the 2010 revolution represented a turning point in the welfare state trajectory as the newly formed government put welfare state reforms at the forefront of its agenda. As such, one of its first actions was to roll back tariff increases and expand public social benefit levels for all citizens (OECD, 2018). Meanwhile, the government also adopted the Den Sooluk (2012–2018) reform and the Healthy Person-Prosperous Country programme (2019–2030) to improve health outcomes and the quality of public healthcare services, as well as the Country Development Strategy 2007–2010, in which the government increased state funding for education and provided broader access to education services.

Despite these healthcare reforms, by 2020, social insurance programs, particularly old-age pensions, dominated the Kyrgyz welfare state in terms of coverage, funding and expenditures (OECD, 2018). Furthermore, although the president repeatedly emphasized education's importance to its citizens' well-being (see the 2012 Education Development Strategy of the Kyrgyz Republic6), very few education reforms were instituted to improve service quality and coverage.

Tajikistan

Compared with Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan's welfare state historically has been characterized by financial imbalance, inadequate coverage, limited expenditures, difficult access to social services and poor distribution mechanisms (Son, 2011). Since it became independent, limited progress has been made to overhaul these weaknesses, and few reforms have been implemented.

When examining the healthcare sector, like Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan inherited a highly centralized health system administered along three main management levels – national, regional (oblast) and district (rayon). By 2003, the tax-funded public health sector still was divided along these three management levels, with the central government in charge of the administration of social services (Müller, 2003). Importantly, inspired by the welfare reforms in the Kyrgyz Republic, the Tajik government planned several policy documents to guide the reform process in the healthcare sector as part of the Somoni Programme in 2005, but only recently some reforms were adopted, including the National Health Strategy (NHS) for 2010–2020 and the Health Financing Strategic Midterm Plan for 2015–2018 to strengthen primary healthcare and increase public financing in health policy. However, major problems – e.g., operational issues related to service delivery, a fragmented administrative coordination, a lack of a privatization policy strategy and difficulties aligning external aid – made healthcare reforms in Tajikistan relatively slow compared with those in Kazakhstan and the Kyrgyz Republic (Mirzoev et al., 2007). Today, Tajikistan's healthcare system is not much different from how it was organized during the Soviet era (Khodjamurodov et al., 2016).

However, some minor reforms in education and social protection have been adopted. As for education, the government adopted the Law on Education in 1993, which established private education institutions. Since then, the nation has seen a proliferation of new higher education institutions and universities, most serving as Tajik branches of international universities (Asian Development Bank, 2013). In particular, a bilateral agreement with Russia helped establish and proliferate several higher education institutions, and increase the number of programs and enrolment in far-reaching regions of the country. More recently, the government, together with the Ministry of Education, adopted several education policy initiatives, e.g., the National Strategy for Education Development of the Republic of Tajikistan (2006–2015) and the National Strategy for Education Development of the Republic of Tajikistan until 2020, under the supervision of international actors, e.g., the World Bank and UNICEF (DeYoung et al., 2018). However, despite several policy initiatives, a deeper examination of the education system reveals that major changes occurred only within the preexisting Soviet structure, and only a few minor adjustments were made.

Finally, as for the social protection system, the government adopted several reforms since it became independent in 1991, but these reforms have come under increasing fiscal pressure and in most cases have not produced substantial changes (Son, 2011). For example, social protection expenditures continue to be largely dominated by pension programs, i.e. old-age pension, disable pension and survivors pension, while social assistance programs remained underfinanced. Only in 2016 the government launched the first National Development Strategy of the Republic of Tajikistan aiming to increase social protection spending, improve living standards through sustainable economic development, raise the middle class up to 50% of the population and eliminate extreme poverty by 2030. However, a most recent assessment of the Strategy does not provide evidence of radical and substantial changes in social protection in the country (see Mirzoev, 2022).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In his 1991 study, Bennett asked, ‘Is policy convergence still a useful idea?’ (217). Since then, several scholars have demonstrated how policy convergence helps capture similarities within distinct policy fields. However, only limited attention has been paid so far to whether and how the notion of policy convergence can be applied to nondemocratic regimes.

Taking Bennett's (1991) question seriously, the present study demonstrates how the notion of policy convergence is not only useful for capturing cross-national similarities in welfare state development in nondemocratic regimes, but also helps untangle differences in the characteristics of the policy under investigation. The empirical analysis yields evidence of a broad welfare state convergence in the FSU countries when examining social expenditure levels, particularly in health and social protection, as well as a common shift toward higher levels of tax revenues to finance welfare provisions. However, when examining old-age pension and unemployment programs' generosity and inclusiveness, strong evidence of a convergence trend was not found, i.e., there has been a general increasing trend in coverage and benefit levels in both old-age pensions and unemployment programs, suggesting that after an initial period of liberal market reforms, FSU countries are moving toward more inclusive and generous welfare systems. However, these trends do not strongly suggest that policy convergence is taking place. Instead, cross-countries variation in the degree of generosity and (partially) extent of inclusiveness for old-age pension and unemployment programs persists.

Furthermore, the study of major welfare reforms in the selected countries yields a divergence pattern. In particular, major reforms in the health and social protection realm have been adopted in Kazakhstan, moving away from a neoliberal approach in welfare reforms that has long dominated the transition phase, while no major reforms were adopted in the education sector. Instead, the welfare state in the Kyrgyz Republic still skews heavily toward healthcare and social security programs, particularly old-age pensions. Finally, Tajikistan remains the welfare state laggard, as only minor adjustments in the welfare state have been adopted since it became independent, as it remains anchored to the old Soviet architecture.

Overall, at least three broad lessons can be taken from this comparative investigation of policy convergence. First, policy convergence is a useful concept for capturing similarities across countries, but the results are driven mostly by the characteristics of the policy under investigation. The empirical analysis supports the argument for a broad welfare state convergence when comparing certain policy indicators, particularly social spending and welfare funding, but it does not sustain the convergence hypothesis when welfare programs' institutional characteristics are scrutinized. Therefore, policy convergence on certain policy characteristics might be paralleled by divergence in other aspects or characteristics of the same policy. This evidence also explains why the research on welfare state convergence across EU and OECD countries reveals a similar asymmetry in the results. As such, similar to the work of Heichel et al. (2005), this study invites us to elaborate a common theoretical ground which takes into account the characteristics of the policy under investigation in order to scrutinize cross-national policy convergence fully.

Second, authoritarian regimes just as democracies have incentives to pursue similar or identical policy decisions. In the past two decades, public policy research on nondemocratic regimes has shed light on how institutions – e.g., elections, legislatures and parties – affect distinct policy decisions and outcomes (Gandhi, 2008; Knutsen & Rasmussen, 2018; Panaro, 2022; Panaro & Vaccaro, 2023; Pelke, 2020; Teo, 2019; Williamson & Magaloni, 2020). This ‘institutional turn’ (Pepinsky, 2014) in the public policy scholarship on authoritarian regimes has paid particular attention to cross-national variation due to domestic political and institutional dynamics. Au contraire, the analysis on welfare state convergence in post-Soviet autocracies suggests that, in addition to political and institutional context, there are some reasons why autocratic incumbents may adopt similar or equal social policy decisions. For example, authoritarian leaders might have interests in emulating neighboring countries (see Tajikistan) or pursing international actor's recommendations. This article demonstrates that welfare reforms in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan were only possible with international organizations' technical and financial support. Future research should further explore these potential propositions, i.e. actor's interests to emulate and the role of international organizations, to move toward to a better understanding of policy decisions in authoritarian regimes.

Finally, a major implication conceives of research on FSU countries. Similar to Cook and Titterton (2023), this article confirms the convergence hypothesis only in certain policy areas, namely social protection and (partially) health policy, while divergence persists in education policy. Particularly interesting is the case of Kazakhstan, which moved from a fiscal to an occupational welfare system, with tax revenues as a source of welfare funding reduced and social contributions increased. Conversely, the findings show that tax revenues and social contributions to finance the welfare state increased in the Kyrgyz Republic and Tajikistan.

In light of this evidence, examining why some FSU countries are moving toward an occupational welfare while others are re-establishing tax revenues as their main source of welfare funding is an interesting and promising avenue for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to Andreas Heinrich, Annemieke van den Dool, Caroline Schlaufer, Gulnaz Isabekova, Heiko Pleines, Veronica Sandu, participants at the 2022 European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR), participants at the 2019 International Conference on the post-Soviet region, University of Bremen, and the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from any public or private funding agency.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Endnotes

Biography

Angelo Vito Panaro is a postdoctoral researcher at Bielefeld University and adjunct professor at the University of Bologna. He studies how institutions, national political dynamics and international organisations influence social policy, welfare reforms and inequalities, with a particular focus on authoritarian contexts. His key research areas are comparative welfare state, social policy, global redistribution, and comparative authoritarianism.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The author confirms that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.