Upstream and downstream implementation arrangements in two-level games. A focus on administrative simplification in the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan

Abstract

enThe onset of the European NGEU program represented for European member states a formidable opportunity for post-pandemic recovery and yet a significant challenge at the same time: to receive and retain EU funds, each state had to promptly draw up a National Recovery and Resilience Plan—NRRP) and commit to a pressing timetable for its implementation. Regarding this challenge, the Italian government's response is a case in point: first, Italy is by far the largest beneficiary of NGEU funds; second, it has long had a reputation for being laggard in both the implementation of European directives and the spending of cohesion policy structural funds; and the formulation of the NRRP, the design of the governance in charge of its implementation, and implementation itself, occurred at a particular moment in the country's political life. Based on these premises, the article examines the upstream process by which the Italian government designed the implementation arrangements for the adoption of simplification policies under the NRRP and their downstream recalibration in the first two years, taking the implementation arrangements as the dependent variable. Analytically, the focus is on the interplay between the pressures of EU timetables and internal political dynamics, be they the legacy or strategic political considerations on the part of national policymakers, in determining the design and eventual re-design of implementation arrangements as the plan unfolds.

摘要

zh“下一代欧盟”计划的启动为欧盟成员国带来了疫情后复苏的巨大机遇,但同时也带来了重大挑战:为了接收和保留欧盟资金,每个国家必须迅速制定“国家复苏与复原力计划”(NRRP)并承诺制定紧迫的实施时间表。对于这一挑战,意大利政府的响应是一个很好的例子:第一,意大利是迄今为止“下一代欧盟”计划资金的最大受益者;第二,它长期以来在“执行欧洲指令和支出凝聚政策结构基金”方面是出了名的落后;NRRP的制定、负责其实施的治理设计、以及实施本身,都发生在该国政治生涯的特定时刻。基于这些前提,本文以实施安排为因变量,分析了意大利政府“为采纳NRRP简化政策而设计的实施安排”这一预先过程以及过程开始后的前两年所出现的调整。从分析层面来讲,本文聚焦于:伴随计划的展开,在确定实施安排的设计和最终的重新设计一事上,欧盟时间表带来的压力与内部政治动态(无论是国家决策者的遗留影响还是战略政治考虑)之间的相互作用。

Resumen

esEl inicio del programa europeo NGEU representó para los estados miembros europeos una formidable oportunidad para la recuperación pospandémica y, al mismo tiempo, un desafío importante: para recibir y retener fondos de la UE, cada estado tuvo que elaborar rápidamente un Plan Nacional de Recuperación y Resiliencia.—NRRP) y comprometerse a un calendario urgente para su implementación. Respecto a este desafío, la respuesta del gobierno italiano es un buen ejemplo: primero, Italia es, con diferencia, el mayor beneficiario de los fondos del NGEU; en segundo lugar, desde hace mucho tiempo tiene fama de estar rezagado tanto en la implementación de las directivas europeas como en el gasto de los fondos estructurales de la política de cohesión; y la formulación del NRRP, el diseño de la gobernanza encargada de su implementación, y la implementación misma, ocurrieron en un momento particular de la vida política del país. Con base en estas premisas, el artículo examina el proceso inicial mediante el cual el gobierno italiano diseñó los acuerdos de implementación para la adopción de políticas de simplificación bajo el NRRP y su recalibración posterior en los primeros dos años, tomando los acuerdos de implementación como la variable dependiente. Analíticamente, la atención se centra en la interacción entre las presiones de los calendarios de la UE y la dinámica política interna, ya sean el legado o consideraciones políticas estratégicas por parte de los responsables de las políticas nacionales, a la hora de determinar el diseño y eventual rediseño de los acuerdos de implementación a medida que se desarrolla el plan.

INTRODUCTION

The onset of the European Next Generation EU (NGEU) funds represented for European member states a formidable opportunity for post-pandemic recovery and yet a significant challenge at the same time: to receive (and retain) the lavish funding, each state had to promptly draw up a six-year investment and reform plan (the so-called National Recovery and Resilience Plan—NRRP) following the European Commission's recommendations, and commit to a pressing timetable for implementing the envisaged policy measures, under threat of suspending and retrieving the allocated funds. Setting up implementation arrangements to carry out the plans timely and effectively is, therefore, a key ingredient in the strategies devised by governments to seize the opportunity provided by the NGEU funds.

Regarding this challenge, the Italian government's response is a case in point. Not only Italy was the largest beneficiary of NGEU funds, but also has a long tradition of poor implementation of European directives and sluggish spending of cohesion policy structural funds (Börzel, 2000), also due to the poor administrative capacity of its public administration (Milio, 2007); the latter being a problem exacerbated by the austerity-era policies of spending cuts and hiring freeze (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2023). Last but not least, the formulation of the Italian NRRP, the design of the governance in charge of its implementation, and implementation itself occurred at a particular moment in the country's political life, namely with the transition from a center-left government led by the leader of the populist Five Star Movement party, Giuseppe Conte, to a grand coalition government headed by the former President of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, and then again to a government led by the leader of the far-right party Fratelli d'Italia, Giorgia Meloni.

Based upon these premises, this article aims to examine the upstream process by which the Italian government designed the implementation arrangements for enacting the NRRP and their downstream recalibration over the first two years (from mid-2021 to date). The focus will be on the setup and working of the implementation structures in charge of carrying out administrative reform (which is designed as a cross-cutting and functional pillar for all measures in the plan), and specifically on the field of administrative simplification, which is one of the critical areas targeted by the European recommendations to Italy (Di Mascio, 2020).

Theoretically and analytically, the article looks at the implementation arrangements (and, more specifically, their organizational component) as a dependent variable to reflect upon the interplay between the pressures exerted by EU timetables and internal political dynamics, in determining the design and eventual recalibration of the implementation structures as the Plan unfolds. In this way, the article stands at the crossroads between implementation studies and the literature on the Europeanization of national policies. It thus contributes to the cross-fertilization of two important streams of public policy research (Thomann & Sager, 2017).

The article is structured as follows: Section “Designing Implementation Arrangements in Multi-Level Settings: Multiple Times and Two-Level Games” presents the theoretical-analytical framework that frames the research question and hypotheses addressed in Section “Research Design and Methods”. Section “The Design and Implementation of Simplification Policies Before the NRRP: The Legacy” presents the legacy of simplification policies in Italy by reconstructing the characteristics of the structures in charge of their implementation from the 1990s until the recent pandemic crisis. Section “Simplification in Turbulent Times: From the Covid-19 Pandemic to the NRRP” provides an analytically informed empirical account of the design of the implementation arrangements for ‘grounding’ the administrative simplification interventions envisaged by the NRRP, and the changes made along the way by the three successive government majorities in the period 2020–2023. Finally, in Section “Discussion and Conclusion” research findings are discussed and conclusions are drawn.

DESIGNING IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS IN MULTI-LEVEL SETTINGS: MULTIPLE TIMES AND TWO-LEVEL GAMES

Since the pioneering work by Pressman and Wildavsky (1979), most implementation studies have focused on the problem of policy failure or, put another way, the implementation gap. In all three generations of research on the topic (Goggin et al., 1990), albeit with different approaches and methodological traditions, scholars' attention has primarily turned to distortions in the implementation process resulting from the interdependence of stakeholders, multiple organizational logics in implementation structures, or, broadly speaking, the complexity of joint action. In this vein, implementation arrangements and their characteristics have generally been analyzed as one of the independent variables affecting the degree of policy goal achievement (Casula, 2022).

Yet, here we take a different perspective: assuming that “the roots of implementation problems can often be found in the prior policy formulation process” (Winter, 2006, p. 155), we address the factors influencing the choice and design of implementation arrangements entrusted with the realization of administrative simplification policies within the Italian NRRP, treating the latter as a dependent variable. Indeed, implementation arrangements are a vital part of decision-making insofar as they represent the “structural” component of a policy (Sager & Gofen, 2022): determining how a policy is to be implemented (i.e., through which structures, roles, and interplay among all the various actors involved) is (or, at least, should be) an integral part of its design along with the policy tools that were selected and the causal theories underpinning public intervention (Hill & Hupe, 2002).

As Sager and Gofen (2022) point out, implementation arrangements result from the combination of two structural dimensions, namely, institutional setting and organizational design. Specifically, the institutional setting is exogenous to the formal policy decision and provides the restraining and enabling context within which the policy must reach its goals. In contrast, the organization is a part of the policy design, and it defines the competences of and the resources available to the implementing agents. While the institutional setting tends to be stable over time because it embodies values and crystallizes interests, the organizational component deals with the strategies for the division of labor and internal coordination developed from time to time to cope with specific problems, and is therefore consumable, instrumental, and adaptive (Selznick, 1957). Indeed, especially if a program, or an intervention, is being planned that will take a long time to complete, implementation cannot be seen as a monolithic phase but instead will be studded with sequences and rounds due to various reasons: failures of previous rounds; changes in the context (social, economic, political, etc.); the temporal intersection with other policy streams; or even political/strategic considerations of the actors involved (Mahoney, 2000; Pollitt, 2008). In this vein, the “time inside policy” (Capano, 2009) may drive toward a more dynamic organizational design: as the implementation process goes on, and depending on how it proceeds, decision-makers may revise their upstream choices about the organizational layout of the implementation structures making accommodations that reflect their own instrumental considerations.

The above considerations are more so true in multi-level policy formulation and implementation processes, where European institutions are also involved. Indeed, the literature on the Europeanization of public policies has repeatedly highlighted the relevance of the temporal dimension for domestic policy making, showing how and how much EU “governing by timetables” (Goetz, 2009) led to a “squeezed national present” in national administrations (Ekengren, 2002). As Goetz and Meyer-Sahling argue (2009, p. 181), “if we understand better ‘how the EU ticks’ […] we will also gain insights into how it distributes opportunities for effective participation in decision-making” at the domestic level. Under the European governance system, national governments have less room for maneuver and autonomy in their choices concerning the domestic political time (e.g., time budgets, time horizons, time rules), as they have to comply with “different decision-making rhythms and detailed calendars of supranational processes of decision-making and negotiation” (Jerneck, 2000, p. 39) that reduce flexibility in the discretionary use of temporality. In this light, when it comes to the formulation and implementation of EU-funded multi-annual programs, national governments come to play a two-level game (Ongaro et al., 2022; Putnam, 1988), in which they struggle to accommodate the demands (and timeframes) dictated by supranational institutions with the temporal priorities and time horizons of domestic actors (e.g. political parties, interest groups, regional and local governments, bureaucracies). For instance, the literature on the use of EU structural funds has repeatedly pointed to the importance of domestic political variables, such as political instability or the frequent change of government parties, in explaining problems and delays in the implementation of EU-funded programs (Hagemann, 2019; Milio, 2008).

On this basis, we assume that the characteristics of the European Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and the rules underpinning its working may have an impact not only on the content of domestic policies and reforms, as highlighted by the most recent literature on Europeanization (Bokhorst, 2022), but also on the design of the arrangements in charge of their implementation. As various scholars have pointed out, compared with already established conditionality mechanisms at the European level (i.e. those underlying the European Structural and Investment Funds, and those linked to the Country Specific Recommendations—CSRs—that are issued in the context of the European Semester), the RFF introduces relevant innovations that reflect a new “performance-based approach” which makes disbursing EU financial assistance conditional on respecting an Operational Arrangement signed between the European Commission and national governments (Bokhorst & Corti, 2023; Corti & Vesan, 2023).

This agreement is the formal act (a kind of contract) that sets out the mechanisms for regular (every 6 months) monitoring of the achievement of a detailed set of qualitative and quantitative objectives (milestones and targets) necessary for the recognition of reimbursement tranches, which are only paid if these deadlines are met by each Member State. It implies that, in addition to ex ante thematic conditionality, which links the approval of multiannual program funding to their alignment with EU policy objectives and CSRs, the implementation of national recovery and resilience plans will be subject to continuous scrutiny by the Commission, both upstream, for the credibility of commitments and timelines, and downstream on an ongoing basis, for their fulfillment on which the payment of installments depends.

The resulting pressure on the design of implementation arrangements is evident: on the one hand, “all parts of the policy machinery […] need to deliver in order for milestones and targets to be met” (Bokhorst & Corti, 2023, p. 4), bringing to the fore the problem of developing effective task allocation and coordination mechanisms at the domestic level. On the other hand, the role of the European institutions as active players in the implementation of domestically planned reforms and interventions is strengthened in comparison to the past, both ex ante, when the Commission approves the national recovery plans, and ex post, during the monitoring process, when the actual disbursement of funds depends on continuous assessments of the timing and scope of implementation (Domorenok & Guardiancich, 2022).

In this regard, some scholars hypothesize a strengthening of the European institutions' capacity to induce Member States' reforms through their recommendations (namely “coercive Europeanization,” see Ladi & Wolff, 2021): detailed milestones and binding targets, coupled with the large amount of financial resources associated with the RFF and made available at such a critical post-pandemic time, have certainly been a powerful tool for complying with EU recommendations, in particular for those governments receiving the larger amounts of funds (Bokhorst & Corti, 2023). On the other hand, others highlight how the European Commission, in its contractual relationship with the member states, cannot do without recognizing a certain room for national ownership in order to ensure that the reforms and interventions undertaken produce effects in the long term, and that therefore “the definition of reforms and investments in the plans ultimately result from an iterative process” (namely “coordinative Europeanization”) between the European and the domestic levels (Corti & Vesan, 2023, p. 517).

So far, the debate has mainly focused on the formulation and thus the substantive dimension of the reforms (and more generally of the national policies) affected by the RFF, while the issue of how the European level is capable of altering the organizational dimension of the implementation arrangements has remained on the back burner. Yet, the tension between the coercive and coordinative dimensions of the RFF regulations is particularly evident precisely with regard to the governance of the implementation of the National Recovery and Resilience Plans, where Member States are recommended to foster the involvement of territorial autonomies and stakeholders, without however indicating specific organizational models as is the case, for instance, for the implementation of the Structural and Investment Funds under the cohesion policy (Profeti & Baldi, 2021).

In this article, we therefore attempt to address this gap by bringing into dialogue the most recent literature on the Europeanization of domestic policies and the perspective of implementation arrangements, in order to see whether, how and to what extent the European level, thanks to the European Semester and the introduction of the RRF, is capable of altering implementation structures at the domestic level in the direction of a performance-based approach. Italy is a case in point for addressing this issue. First, Italy was by far the largest beneficiary of the RFF, being the European country most affected by the pandemic, and this is expected to set strong incentives for domestic actors to comply with European recommendations. Second, Italy has long had a reputation for being particularly laggard in implementing European recommendations (Börzel, 2000), as well as in spending cohesion policy structural funds (Milio, 2007), and can thus plausibly be considered a designated “special observer” by the Commission both during the formulation of the Plan and during its implementation. Third, the formulation and early implementation of the Italian NRRP were carried out by three different government coalitions with very different compositions and ideological orientations (including their attitude toward the European institutions): the center-left government led by the 5-Star Movement leader Giuseppe Conte; the grand coalition government led by former ECB President Mario Draghi; and the center-right government led by Giorgia Meloni, leader of the far-right Fratelli d'Italia party. Apart from the Draghi government, the leadership in the other two cases is in the hands of populist parties with Eurosceptic overtones (Di Mascio et al., 2023).

On the one hand, this peculiar configuration of domestic politics could suggest that the European institutions should take particular care to use the performance-based approach to tie the hands of the Italian governments as much as possible, in order to shelter the plan's advance from political turbulence; on the other hand, however, it could also highlight the Commission's need to adopt some margin of flexibility in the monitoring and negotiation of possible changes in the Plan, both for reasons of feasibility, and—in terms of legitimacy—to leave the national government with some ownership of the Plan's contents and progress (Bokhorst & Corti, 2023).

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Building on the analytical framework outlined above, the research question we intend to answer in this article is whether and to what extent the performance-based approach associated with the functioning of the RFF has brought about a watershed in administrative simplification policies in Italy, enhancing the capacity of the European level to alter the organizational dimension of implementation arrangements. The focus on administrative simplification is justified by the constant presence over the last ten years of this topic among the CSRs received by Italy, together with other interventions oriented toward the modernization of the public administration. Insofar as it is geared toward reducing bureaucratic burdens and streamlining the functioning of the public administration, simplification is also fundamental to the possibility of meeting the tight deadlines dictated by the NRRP on the investment front, and is thus an extremely salient policy area in the eyes of both the European Commission and the various stakeholders involved in the implementation of the Italian NRRP.

As we highlight in the next section, the organizational design of implementation arrangements in the field of administrative simplification has been traditionally at odds with the EU's championing of performance-based approaches. This encouraged us to draw on research arguments typical of the historical institutionalist approach that stress the importance of early events for later occurrences. Most historical institutionalist research has used the theory of punctuated equilibria, which adopts the following explanatory approach: an event or a series of events, typically exogenous to the institution of interest, leads to a relatively short period of uncertainty (“critical juncture”) in which different options for change are available; the selection of one of these options generates a long-lasting institutional arrangement (Capoccia, 2015). However, the response of decision-makers to an exogenous event will depend on feedback effects arising from commitments to existing institutions. If these effects make the cost of exiting from established arrangements rise, it is likely that the exogenous event will eventually lead to restoring the status quo. This is the typical path-dependent pattern marked by a “self-reinforcing” sequence of events characterized by the long-term reproduction of institutional arrangements (Pierson, 2004).

Most recent studies of policy change have increasingly moved away from the dichotomy between rare and rupture-like change on the one hand and powerful path-dependencies implying little if no change on the other (Howlett, 2009). These studies have understood policy making as involving the connections between events in different time periods as reiterated problem-solving, meaning that event chains are demarcated on the basis of contrasting solutions for recurring problems (Haydu, 2010). In other words, previous solutions to a recurring problem will influence the instruments and the interpretations available to future actors. This approach is consistent with those accounts of path dependence that understand historical trajectories as “reactive sequences,” in which early events trigger subsequent developments not by reproducing a given pattern, but by setting in motion a chain of tightly linked reactions and counterreactions (Mahoney, 2000). Reactive sequencing leaves more room for change within the path and it is part of a broader analytical shift from the traditional focus of historical institutionalism on institutional reproduction to a new wave of studies that focus on gradual, endogenous change (Mahoney & Thelen, 2010).

As outlined in the next section, the introduction of an organizational design in line with the performance-based approach has constituted an enduring problem in Italy where the institutional setting has largely inhibited the implementation of European recommendations. The powerful role of the legacy of the old regime that has marked the historical trajectory of the administrative simplification policy before the outburst of the pandemic and the launch of the RRF led us to put three scenarios to the empirical test, each one based on hypotheses drawn from the historical institutionalist wave of research:

Scenario 1—The pandemic and the launch of the RFF as a “critical juncture”

The economic crisis and the conditionality attached to the NRPP constitute exogenous conditions maximizing the influence of the European recommendations (i.e., coercive Europeanization), eventually leading to a radical shift in the organizational design of implementation arrangements;

Scenario 2—Self-reinforcing sequencing

Political elites faced a persistent institutional setting and the high volatility of the political environment made actors more likely to rely on existing organizational arrangements since the faster events unfold, the shorter the time horizons and the consequent ability to design alternative solutions;

Scenario 3—Reactive sequencing

The RFF has only partially contributed to boosting Italy's compliance with the European recommendations given the persistent institutional setting and the frequent government turnover. This notwithstanding, the RFF has contributed to the introduction of new features of the organizational design, which would have been on paper without the conditionality attached to the RRF. The latter has introduced an unprecedented architecture for multi-level collaboration between the EU and its Member States (i.e., coordinative Europeanization) in which European and domestic actors react to each other by drawing lessons from experiences of success and failure.

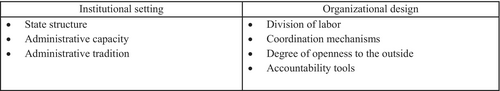

Our analysis of the administrative simplification policy in Italy unpacks the two dimensions that constitute the implementation arrangements (i.e., institutional setting and organizational design) into sets of features as illustrated in Figure 1. As regards the institutional setting, we identify three key features that typically provide the enabling and restraining context within which administrative simplification strategies must reach their goals. The first feature refers to the state structure, which affects the vertical dispersion of authority between different levels of government as well as the degree of horizontal coordination at the central government level (Pollitt & Bouckaert, 2017). This feature is particularly relevant given that the need for effective coordination between government departments and between levels of government has become pressing in relation to implementing administrative simplification (OECD, 2003). The second feature refers to administrative capacity, which is understood as the ability to manage efficiently the human and physical resources that are required for delivering the outputs of government (Painter & Pierre, 2005). This feature is particularly relevant given that having an insufficiently skilled and ill-equipped team working on administrative simplification will likely prevent governments from meeting ambitious expectations (OECD, 2020). The third feature refers to administrative tradition, which has been defined as a historically based set of values, structures, and relationships with other institutions that define the nature of appropriate public administration within society (Peters, 2021). The administrative tradition may represent a key barrier to administrative simplification in those countries where public administration is not expected to embrace continuous change so as to better address the citizens' priorities (OECD, 2009).

The institutional setting represents the (quite) stable background system of constraints and opportunities within which the specific organizational arrangements crucial to implementing administrative simplification strategies are designed. In fact, the implementation of typical simplification measures, such as the reduction of red tape for citizens and businesses or the streamlining of bureaucratic procedures, requires a balance to be struck between the necessary distinction of roles and functions (between the various administrative structures or between the center and the periphery) and the development of coordination mechanisms (whether hierarchical, based on digital technologies, or relying on shared technical assistance and training tools for the operators) that avoid fragmentation and redirect the division of labor toward a single, coherent objective. The implementation structures may also be more or less open to the external environment, that is, to possible inputs and feedback from the various institutional and private stakeholders who have direct knowledge of the needs and difficulties when it comes to realizing simplification measures. Last but not least, the organizational design of the implementation arrangements should also take into account accountability mechanisms to provide a means to evaluate whether the simplification efforts are achieving their intended goals. This sub-dimension covers, for example, the level of detail in defining objectives, deadlines, and responsibilities for interventions and the characteristics of the monitoring and evaluation system (OECD, 2009). Figure 1 summarizes the dimensions on which we grounded the analysis of simplification policy implementation arrangements.

Empirically, our study follows a qualitative approach based on an analytically based historical account of the design and early working of the implementation arrangements designed to carry out the administrative reform measures included in the Italian NRRP, paying particular attention to administrative simplification measures. Data were collected using source triangulation to ensure the validity of findings (Patton, 1999): the review of official documents (e.g., the NRRP and the resulting primary and secondary legislation) and institutional monitoring reports were complemented with a press review on some national newspapers and followed by a number of interviews1 with key informants that allowed aspects of the decision-making processes that we could not deduce from the documentary analysis to emerge.

THE DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF SIMPLIFICATION POLICIES BEFORE THE NRRP: THE LEGACY

Administrative simplification policies were born in Italy in the early 1990s out of the need to make the country attractive for business and investment in a context in which the freedom of movement introduced by the EU and economic globalization intensified the urgency for all advanced countries to increase their competitiveness. Both the formulation and implementation of administrative simplification measures have constantly been affected by some typical features of the post-World War II Italian institutional setting.

First, as far as the State structure is concerned, since the 1990s a series of reforms have focused on the balance of power between the center and the periphery and, in particular, between the State and the regions, moving toward a quasi-federal system (Lippi, 2011); however, non-completion of these reforms and the provision of many subjects for concurrent competence in the absence of robust venues for interinstitutional collaboration have fostered competitive dynamics between the center and the periphery, marked by frequent disputes and blame-shifting mechanisms, such as those highlighted during the recent pandemic emergency (Baldi & Profeti, 2020). Furthermore, these institutional engineering efforts have not been accompanied by an equally intense political commitment to reforming (and simplifying) the working tools of the public administration, which have long remained in the background, limited to cases where simplification measures were imposed by changes in the external environment, as in the case of the economic and financial crises that have followed one after the other since Italy entered the European Single Market.

Second, Italy's legalistic Napoleonic tradition, which matches the continental model of strictly regulated administration (Gualmini, 2008), has strongly influenced “how” such simplification attempts have developed from the very beginning, namely through the adoption of legal norms: to simplify a procedure strictly regulated by law, one needs to pass other laws. This propensity to “simplify by law” was amplified by the endemic fiscal crisis that plagued Italy since the early 1990s, which prompted the adoption of simplification measures subject to the so-called no-cost financial clause: in essence, administrative procedures were to be accelerated without any investment in some new administrative capacities or information technologies. In addition, an enormous stock of bureaucratic burdens had been accumulating since the beginning of the last century as a consequence of the pervasive control over civil servants' discretion on the part of the Italian ruling classes, who saw bureaucracy more as an instrument for obtaining and maintaining political consensus than a tool for economic development. For this reason, administrative procedures ended up being bound by increasingly stringent rules, and little attention to substantive results was paid.

Last but not least, the weak—and territorially uneven—administrative capacity of the Italian public administration, also highlighted by some studies on the spending capacity of European funds (Cunico et al., 2022; Milio, 2007), has been an obstacle to simplification policies. Such shortcomings have been exacerbated by the austerity measures introduced after the 2008 global crisis, which have also affected the civil service. For example, hiring restrictions have led to an increase in the average age of the workforce, especially in the southern regions and local authorities, which already were facing the most serious deficits in administrative capacity. The demographic aging of public employees, combined with the drastic reduction in spending on training (46% over the period 2008–2017), has exacerbated the problem of skills shortages, especially technical and digital skills (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2023). Indeed, these skills are necessary in a rapidly changing sector such as the one in which public organizations are forced to operate, and are fundamental to simplification.

Along these lines, simplification policies of the last 30 years in Italy have always been a mix of regulatory interventions pursuing different aims: some affected the general discipline of administrative procedures contained in Law no. 241/1990, which over time has been amended 45 times by other laws, leading to a situation of perennial instability of the regulatory framework. Others focused on specific procedures or even single bureaucratic burdens to make them less demanding for the private sector. Others still were merely symbolic, with laws declaiming principles without any implementation provisions, such as the one according to which public administrations for every burden introduced should abolish an equivalent one. In the face of real emergencies, which called for faster decision-making and less paperwork, the weaknesses of simplification policies were filled by resorting to special procedures that derogated from ordinary ones and were governed by exceptional rules (a kind of “two-track model”) (Di Mascio et al., 2020).

As simplification was essentially entrusted to rules, designing specific organizational settings for their implementation has long remained on the back burner. As regards the division of labor, the number of civil servants and public managers who plan simplification policies in Italy steadily kept on being small and highly concentrated in a few structures in central government. All competencies have been constantly centralized and concentrated in the hands of the Department for Civil Service (DCS), with the passive and sometimes reluctant participation of the other Ministries. A community of experts in charge of designing simplification measures has built up over time at DCS, gradually changing its composition: while it was initially composed essentially of legal experts, later on—also as a result of the European pressure to use new simplification tools such as the Regulatory Impact Analysis or the Standard Cost Model—it was increasingly mixed with experts from different backgrounds such as economists, statisticians, public policy analysts, and communicators. However, the capacity to coordinate the implementation of these measures in every single public administration remained very weak since DCS civil servants “directly reduced administrative times and costs rather than helping other administrations to do the job themselves” (Natalini, 2010, p. 338).

The network of actors involved in simplification policy design somewhat opened up after the 2001 constitutional reform, which strengthened the legislative powers and autonomy of the Italian regions. Since then, and particularly in the second half of the 2000s, new forms of vertical coordination between the different levels of government (national, regional, and local) were gradually introduced, such as the Permanent Table for Simplification, which was also open to the participation of representatives of businesses, trade unions, and stakeholders in general (increased openness to the outside). Over the past 15 years, these structures have been complemented by repeated online open consultation initiatives aimed at identifying loopholes and absorbing simplification proposals in multi-year planning instruments that were first called the Simplification Action Plan (in 2007) and then the Simplification Agenda (since 2015), in which tasks and responsibilities for implementation were assigned to each institutional actor. Furthermore, all simplification measures launched in that period have been supported by new steering tools such as help desks and guidelines, as well as some monitoring activities (accountability mechanisms). In particular, institutional websites have been set up to track the progress of simplification measures. However, that shift toward more articulated governance of simplification policies seems more relevant to the definition of policy goals (i.e., which procedures to simplify and what to put in regulatory texts on simplification) than to the organizational design of the implementation arrangements. The latter remain somewhat undefined and disengaged from a binding system of deadlines and responsibilities because targets did not stick: if they were not met, they were simply replaced by new ones that were included in the subsequent multi-year planning document.

Against this backdrop, and from a comparative perspective, until 2020 the Italian implementation arrangements have sustained an “ad hoc” approach to the review of existing regulation that differs from the best practices highlighted by the literature on administrative simplification (OECD, 2020). Italian simplification efforts have often been initiated in response to a crisis or to address a more general theme, or to focus on a particular economic activity (Di Mascio et al., 2017). Such an approach, being more selective, tends to be more manageable than comprehensive stocktakes that have been widely used by the trailblazing countries of the OECD, in which formalized stock-flow rules require the removal of existing regulations when introducing new ones, or require public authorities to reduce administrative burdens by certain amounts annually. There has been little or no impact on this front from the numerous CSRs that Italy has continuously received on the modernization and simplification of the public sector from 2012 onwards. Indeed, the vague nature of the recommendations and the almost exclusive reference to administrative simplification as a means of reducing burdens have seriously undermined the effectiveness of the weak conditionality imposed by the European Semester (i.e., limited fiscal flexibility in exchange of compliance with CSRs) and, to some extent, encouraged the selective approach to simplification typical of the Italian case (2020).

SIMPLIFICATION IN TURBULENT TIMES: FROM THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC TO THE NRRP

Italy was the first European country to face the pandemic, which initially had a particularly severe impact in northern regions. In addition to the health emergency, the Covid-19 pandemic caused many knock-on crises affecting society, the economy, and governance (Boin et al., 2021). To cope with the severe economic impact of the mitigation measures, in 2020 the Italian government adopted a series of 13 recovery packages to support people and businesses. This was made possible by the transition of the EU economic governance between the pre-pandemic and post-pandemic periods (Ongaro et al., 2022), which on 23 March 2020 resulted in overcoming the stability pact's constraints on public spending by the “general safeguard clause.”2 Between April and July 2020, a further radical change took place, when for the first time the EU was authorized to raise debt on the financial markets. That provided grounds for launching the NextGeneration EU Plan, which hinges on the adoption of a National Recovery and Resilience Plan in each EU country. Italy benefited the most from this initiative, obtaining EUR 191.5 billion in grants and loan financing at affordable rates, yet facing the need to jumpstart a country's economy that had seen its GDP shrink by 9% in 2020.

The early steps by the Conte II government (July 2020–January 2021)

The Conte II government guided the country through this tricky phase. It was based on a center-left coalition formed by the 5 Star Movement, the Democratic Party and Italia Viva, a party founded by former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi who had left the Democratic Party in September 2019: a very heterogeneous coalition with an extremely thin majority in Parliament. Ahead of drawing up a first draft of the Recovery and Resilience Plan to be sent to the European Commission, the government adopted Simplification Decree-Law No. 76 of July 16, 2020 (then converted into Law No. 120 of September 11, 2020) to lend credibility to the nationally developed policy proposals. To speed up the effective implementation of NRRP projects, government powers of substitution were further strengthened in the event of inaction or delays attributable to other public administrations, and new rules for overcoming disagreements raised in authorization procedures were established. Furthermore, a new edition of the Simplification Agenda for the period 2020–2023 was launched, which consisted of four chapters dedicated to the re-engineering of procedures, the digitization of processes, and the enactment of some targeted actions to tackle the most relevant bureaucratic bottlenecks for the implementation of the NRRP.

In continuity with the past, the Agenda (approved on 23 November 2020) resulted from a concerted process led by the Technical Table for Simplification already set up in 2015 and made up of representatives of the DCS, the Conference of the Regions, ANCI, and UPI (the latter two associations representing Italian municipalities and provinces, respectively). However, several factors were diverting attention from developing a clear blueprint for the implementation of simplification measures: first, at this stage, negotiations with the European institutions focused mostly on the allocation of resources to the country and, as a second step, on compliance with the ex ante thematic conditionality imposed by the NGEU. On the domestic side, the government still had to deal with the health emergency and the flare-up of infections in the fall of 2020, which were top of the agenda. Moreover, with a view to presenting the first draft of the NRRP to Parliament, the internal negotiations between the various governing parties and between the center and the periphery focused mainly on the distribution of European funds between the various tasks and intervention lines. Finally, as far as governance is concerned, the first point of contention was the overall division of responsibilities for the coordination and management of the interventions provided for in the NRRP: on the one hand, the regions accused the central government of not giving them a leading role in implementing the plan (Profeti & Baldi, 2021); on the other hand, within the government majority, Italia Viva contested Conte's governance proposal, that is, a task force coordinated by six special commissioners, stressing the risk of depriving representative institutions of their authority (Capano & Sandri, 2022). The draft NRRP presented to the Parliament in December 2020 suffered from all of these factors: it was a rather vague text in which the measures were not very detailed, and the hypotheses of the reforms were barely sketched out. In this context, simplification occupied little more than one page of the plan, with a general reference to Agenda 2020–23 objectives and no indication of planned implementation methods.

The Draghi government and the economic rebound (February 2021–October 2022)

By the time the NRRP had to be drafted, the coalition that had supported the Conte II government during the first phase of the pandemic response and the European negotiations to launch the Next Generation EU collapsed. In February 2021, with the support of all parties in parliament except the right-wing Fratelli d'Italia led by Giorgia Meloni, Mario Draghi became prime minister. The former position of the head of the government at the European Central Bank gave him immediate credibility with the northern European states and the European Commission. However, this European consensus was also triggered by the adoption of a very detailed and rigidly pre-determined NRRP, with contents, milestones, and targets set within a very short time span (February–April 2021). Admittedly, the rigidity of the Plan was intended to bind even the prime ministers who might later take Draghi's place in a country characterized by strong governmental instability. On the other hand, the political majority that supported Draghi was particularly heterogeneous and was made up of parties that had been at odds with each other for years, all of which were in a state of decline in terms of consensus and eager for it to grow: this is what led to the adoption of an overly broad NRRP that tried to do too many things without considering the real capacity of public administrations to implement them (Di Mascio & Natalini, 2023).

The tight timeframe in which the Draghi government had to adopt the NRRP and get it up and running made it virtually impossible to identify in advance, even with a margin of approximation, the procedural knots that needed to be untangled and thus to put in place a more targeted policy of simplification. This did not prevent the Italian NRRP, approved at the European level at the end of June 2021, from identifying simplification policy as an enabling reform. Simplification measures were to go hand in hand with the overall reform of the public administration, with the aim of increasing the administrative capacity of the bureaucracy and cutting red tape, two requirements made even more urgent by the fact that a large proportion of the NGEU funds were to be allocated by tender. It is no coincidence that one of the first milestones to be achieved by the Italian government, just one month after the adoption of the plan, was the entry into force of the legislation simplifying the administrative procedures for the implementation of the NRRP and the rules for the provision of technical assistance and the strengthening of administrative capacity. Overall, the administrative simplification measures were spread across the 11 milestones and 6 objectives concerning the modernization of the P.A., requiring 12 reform measures and 16 investment lines (and a number of sub-measures) to be carried out between 2021 and 2026. Reforms, that is, legislative interventions, were concentrated in the first two years of the plan's implementation, while planned investments (and thus concrete spending actions) intensified from 2023 onward.3

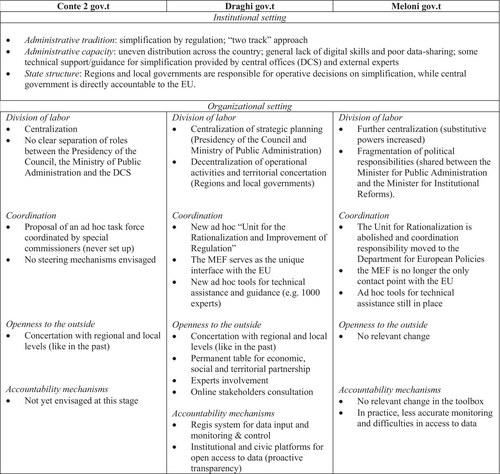

As for the implementation arrangements, due to the time constraints the Draghi government's PNRR almost faithfully incorporated the Conte II government's Simplification Agenda 2020–23, taking up not only its contents—which were made more detailed—but also its method and style. The political pivot of the simplification policy remained the Minister of Public Administration together with the DCS, and the approach was still essentially based on regulatory measures. However, some differences emerged concerning the organizational design responsible for implementing simplification.

With regard to the distribution of tasks/responsibilities and coordination in the implementation of simplification measures, Decree-Law No. 77/2021 provided for the creation of a new ad hoc special Unit for the Rationalization and Improvement of Regulation, based at the Prime Minister's Office. The unit was composed of 7 public managers and civil servants and 10 experts and was tasked with identifying regulatory obstacles in the implementation of the NRRP and formulating proposals to overcome dysfunctions. In addition, for the first time since simplification appeared on the institutional agenda, it was recognized that regulatory measures to reduce or eliminate administrative procedures must be accompanied by new human and technological resources in public administrations in order to be effective (CNEL, 2022). Thanks to the abundant resources made available by the NGEU, the NRRP provides for a temporary (3-year) working group of around 1000 experts to help the administrations map and redesign the administrative procedures that underpin the implementation of the plan, review them in the light of the possibilities offered by digitalization, extend the mechanisms of quiescence-consent and communication, and—not least—reduce the existing backlog. Although the criteria for allocating the 1000 experts to the local authorities were decided in the offices of the DCS without any significant input from the sub-national levels, operational decisions on simplification and on the allocation of the experts to the local administrations were instead decentralized on the regional level. To this end, regional governments had to draw up Territorial Simplification Plans after consulting the associations of local authorities (ANCI and UPI). Each region then proceeded to consult local authorities in a way that was compatible with its territorial governance legacy.

With regard to openness to the outside, the online public consultation “Let's make Italy simple,” launched by Minister Brunetta on 18 February 2022, was presented as the formal and priority channel for the consultation of stakeholders during implementation, in order to identify the most burdensome procedures to be simplified. This was complemented, as regards the general NRRP, by the Permanent Table for Economic, Social and Territorial Partnership, composed of representatives of the regions, local authorities, and socio-economic forces, with advisory functions during the implementation of all measures. However, these provisions just overlaid the old simplification governance without replacing it: as some interviewees pointed out, the consensual approach to simplification that had been in place for years persisted, with the former Technical Committee on the Simplification Agenda remaining the real place for elaboration and discussion between central government (in particular the DCS, but also various ministries), regional and local authorities, and stakeholders.

As far as accountability is concerned, the mechanisms established for simplification measures are the same as those used for the NRRP as a whole. A unified information system (ReGiS) for the monitoring and reporting of individual measures has been established at the Ministry of Economy and Finance—MEF (Law No. 178/2020). The system, which must be updated monthly and is organized into measures, milestones, targets, and projects, is the only modality through which all the administrations and subjects involved in the implementation deposit the data necessary for the monitoring and control of the progress of the interventions provided for in the plan, in order to then receive the funds. All institutional actors involved in the NRRP in different capacities have access to the ReGiS system in consultation mode, including the European Commission, which is thus fully integrated among the actors involved in the implementation phase. Other instruments of external accountability toward citizens and stakeholders are the web portals created by the Government (Italiadomani.gov.it) and by civil society organizations (such as the website of the Openpolis Foundation, Openpnrr.it) to monitor in real time the progress of the implementation of the measures of the Plan, in order to ensure proactive transparency.

Meloni government: All chickens come home to roost (October 2022 to date)

Mario Draghi resigned as Prime Minister on 21 July 2021, a few months before the natural end of the legislature, after mounting disagreements between the majority parties on various issues (from Covid-19 vaccination to the war in Ukraine to family and business support measures). The right-wing coalition led by Giorgia Meloni won the general elections held in September 2022. The new government was confronted with a context made more difficult by the consequences of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict on the economy and inflation, which led to a significant slowdown in the process of economic growth that had begun after the pandemic. At this stage, many of the NRRP's interventions resulted seriously delayed and to a large extent unfeasible. This was confirmed by the European monitoring and by the Italian Court of Auditors (2023). In fact, all the problems caused by the excessive fragmentation of the plan, its inflexibility in the face of the evolving scenario, and its administrative unsustainability had come to light during its implementation.

But the road to the revision of the NRRP was not going to be an easy one. The first obstacle was the European Commission's and the European countries' mistrust of the new Italian government, which has the support of political parties (such as Fratelli d'Italia, but also the League) that even in the recent past have preached sovereignty and have shown little inclination to respect the stability constraint (Conti et al., 2022). Fratelli d'Italia, the new prime minister's party, had also been very critical of the adoption of the Next Generation EU in the European Parliament, abstaining in votes on the issue; at the same time, during their campaign for the general elections, both Fratelli d'Italia and the other parties of the center-right coalition (including Lega and—to a lesser extent—Forza Italia, which were part of Draghi's government) announced their aim, should they win, to significantly revise the Italian NRRP, which they deemed inadequate, somewhat disavowing the agreement signed between the Italian government and the European Union a few months earlier.4 On this basis, it is reasonable to assume that the European institutions would be less lenient in negotiating with Italy than they would have been under Draghi's staunchly pro-European leadership. In fact, the first clashes with the European level were already apparent a few days after the new government took office: after Giorgia Meloni, in her inaugural speech, had denounced the “irretrievable delays” of the NRRP that she had inherited, the European Commission replied rather harshly that the operations carried out by the Italian government were indeed going as agreed and that any adjustments to the Plan could only concern investments (without in any case diverting RFF resources to deal with the high energy prices, as the new government had hoped), but not the promised reforms.5 On the other hand, on the domestic side, another obstacle was the Meloni government's difficulty in renouncing even part of the NRRP's resources (as suggested by some League MPs6), on which economic and social stakeholders had long pinned their hopes, without losing popular consensus. If there was a high price to be paid for changing course or going back on the path set by the Draghi government, the obstacles to the implementation of the planned measures should be removed as soon as possible. Among these obstacles, the inadequacy of the administrative machinery and excessive paperwork were, of course, the main culprits: as the Minister of Economy and Finance, Mr Giorgetti (League), stated: “the reason for the difficulties in implementing the NRRP lies simply in the fact that the bureaucracy of the public sector has been and still is ill-equipped to deal with such demand shocks.”7

In order to deal with such a thorny situation, the Meloni government adopted the solutions typical of the Italian institutional legacy on simplification: simplifying through regulatory acts following the selective approach, which concentrates urgent measures—namely derogations from the ordinary—on the areas directly affected by the NRRP measures. In fact, Decree-Law No. 13 of 24 February 2023 (converted, with amendments, into Law No. 41 of 21 April 2023) provides for a number of micro-simplification measures tailored to different sectors, such as speeding up tenders and contracts by using telematics, reducing time for issuing opinions, digitizing the procedure for installing 4G technology equipment, raising direct contract thresholds for school buildings, streamlining the procedures for installing photovoltaic systems, and simplifying environmental impact procedures for promoting green and renewable hydrogen and for railways. At a more structural level, there has also been a reform of public procurement (Legislative Decree No. 36 of 31 March 2023), with an increase in the possibility of subcontracting and in the thresholds for the use of direct negotiations.

As regards the organizational design of the implementation arrangements, there were some innovations in terms of role distribution and coordination structures, but these concerned the Plan as a whole and not only the simplification measures. Indeed, the Meloni government undertook a general revision of how the NRRP gets managed. The decision was taken to concentrate the coordination of the Plan under the Prime Minister's Office and, in particular, under the Department for European Policies, headed by Raffaele Fitto (Fratelli d'Italia). Officially, this choice was justified by the need to bring the control and coordination of EU funds under a single responsibility: indeed, the “unclear synergy” of the NRRP with the programming of the European Structural Funds 2021–27 (Polverari & Piattoni, 2022) had already been criticized by several parties (including the Regions) since the formulation of the Recovery and Resilience Plan, given the large overlaps of interventions. But there are also those who interpret this move as an attempt to compensate for Meloni's lower authoritativeness (compared to Draghi) by reinforcing the powers of the Prime Minister's Office with respect to the MEF's technical structure.8 Whatever the case, the Unit for Rationalization and Improvement of Regulation (as well as the former Agency for Territorial Cohesion) was abolished and incorporated into a new mission structure which, in addition to assuming the tasks of coordinating the general implementation of the NRRP, became the unique national contact point with the European Commission, replacing the MEF. At the same time, the central government's room for maneuver in exercising its powers of substitution had been increased (e.g., by reducing the deadline for acting from 30 to 15 days) and the ministries responsible for NRRP actions were given the opportunity to reorganize their structures for managing the Plan. As regards the Regions and Local Authorities, like the other administrations, they were allowed to stabilize the hitherto temporary recruitment to meet the needs of the NRRP and to incentivize the managers directly involved in implementing the Plan. Looking at the other organizational dimensions, at least at the formal level, there have been some few changes in the dimensions of openness to the outside and accountability mechanisms, of which the most important is the abolition of the permanent table for economic, social, and territorial partnership envisaged by the Draghi government. Furthermore, at the operational level, various observers have reported delays and incompleteness in publishing data on the implementation of the Plan, and some governmental reluctance to respond to requests for information, even those concerning the proposal to modify the content and scope of investments.9 Indeed, the maxi draft amendment of the NRRP to be proposed to the EU Commission under Article 21 of the RFF regulation took longer than expected and was only submitted by the government on 27 July 2023. Compared to the original claims, and even though it involves as many as 144 measures between investments and reforms, the proposed change—later definitely accepted by the European level in mid-September after intense negotiation with the Italian government—appears more like a request for a partial reshuffling of the deadlines than a distortion of the Plan's contents. An agreement was finally reached on transferring a large portion of the investments taken out of the NRRP to the REPowerEU program (entered into force in March 2023 to deal with the energy crisis resulting from the Russian-Ukrainian conflict), under which use can be made of part of the resources already earmarked for the NRRP, in addition to other sources of financing such as cohesion policy funds, the European innovation fund, national tax measures, and private investments.10

However, all changes addressed above have had little impact on the organizational design of implementation arrangements in the specific domain of administrative simplification. In this respect, the main change under the new government is that political responsibilities are now shared between the Minister for Public Administration, Paolo Zangrillo (Forza Italia), and the Minister for Institutional Reforms and Simplification, Maria Elisabetta Casellati (also of Forza Italia). Indeed, as observed by interviewees, this change does not seem to have called seriously into question the organizational design of the implementation arrangements set before: the DCS and the group of senior managers who have been involved in simplification operations for years, with their administrative capacities and multidisciplinary skills, continue to be the technical pivot around which, albeit away from the limelight, the definition of implementation operations and the coordination with regions and local administrations (and to some extent with stakeholders) revolve, while political coordination now seems even more fragmented than in the past.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

By providing financial resources to the EU Member States, conditional to the implementation of measures listed in the NRPP, the RRF has opened new political and institutional opportunity windows for policy change at the national level. This article has dived into how the RFF has been translated into the organizational design of national implementation arrangements concerning administrative simplification. In doing so, our research contributes to the cross-fertilization of two relevant streams in public policy research, namely implementation studies and the literature on the Europeanization of national policies. The case under investigation was Italy, which displays a puzzling combination between the large amount of funds allocated to dozens of projects that require administrative simplification as a key ingredient for their success on the one hand, and the frequent government turnover occurring in a context marked by an institutional setting unfavorable to the implementation of administrative simplification measures on the other. In this sense, the Italian case can be treated as a crucial case study (Eckstein, 1975) to test the different theoretical propositions made in the literature.

Findings provide support for the third empirical scenario—reactive sequencing—outlined in Section “Research Design and Methods”. On the one hand, pressed by the urgency dictated by European times, all three successive governments have reacted making recourse to the traditional institutional setting that has characterized simplification policy in Italy over the last 30 years, providing preferential lanes that deviate from ordinary procedures for interventions under the NRRP. However, some differences in the organizational design of implementation arrangements are evident when looking at the diachronic evolution of Plan implementation and the succession of national government majorities (see Figure 2). During the first phase under the Conte government, the executive was mainly concerned with negotiating with the European institutions on the amount of funding allocated to Italy and creating the conditions, at least on paper, for the credibility of the NRRP. Issues relating to the design of the overall governance of the Plan and the implementation of the various measures—including those relating to simplification—had been thus left in the background. Some changes were introduced instead under the Draghi government when both European and domestic actors reacted to the failure of previous multi-year implementation of plans for administrative simplification by tightening time constraints and accountability arrangements in the drafting of the NRPP. In this respect, the Draghi Government adopted a strategy based on a mix of measures: it reinforced the entire technical assistance and capacity-building side to be distributed among the various administrations according to their needs; it decentralized to the regional level the operational decisions on how to use the assistance made available and how to proceed with simplification; it strengthened accountability mechanisms and provided for some stable channels for dialogue between the government and stakeholders; and, last but not least, it linked most of the milestones in the first year of the plan to the approval of legislation, which was certainly easier to achieve than the actual implementation of the interventions.11

A reversal occurred during the implementation of the NRPP under the Meloni government. The centralization under the Presidency of the Council of the overall coordination of the NRRP and of all interactions with the European institutions can be seen as a strategic attempt to rationalize the channels of dialogue with the EU, as well as to shelter the process of political reshaping of the plan's goals from the influence of the core of technicians orbiting the MEF. As far as the implementation of simplification measures is concerned, however, the changes so far have not been paramount: apart from the intervention of new exceptional legislative measures streamlining the procedures affecting the NRRP, and some decrease in the openness of the implementation process to the external environment, the design of the implementation arrangements remains essentially intact because it is essential to move the Plan forward. The only key difference, as mentioned above, is that the political responsibility for simplification has been split between two ministries, or even three if one takes into account the overall steering role of the Department for European Policies.

All in all, our empirical evidence substantiates the claim of the emergence of a new mode of coordinative Europeanization not only in the formulation phase of the NRPP but also in the implementation phase. On the one hand, the European Commission has loosened top-down hierarchical steering to ensure ownership by the Meloni government, whose contribution in implementing the NRPP was indeed crucial. On the other hand, the Meloni government was not able to lower the level of ambition pre-agreed in the formulation of the NRPP under the Draghi government to avoid losing any funds to which it was entitled. Our research thus provides support to the hypothesis formulated by previous studies that investigated the formulation phase of the NRPPs: the EU level was able to push hard when it negotiated the contents of the NRPPs with national actors that shared its policy priorities as it occurred in Italy under the Draghi government. Conversely, there was more room for national discretion in terms of steering capacity when political actors who did not fully endorse the policy goals of the EU level were confronted with the implementation of the plans.

However, this does not mean that the performance-based approach behind the RRF is not destined to exert lasting effects on national implementation arrangements. For example, despite the new government's attempts at further centralization and outward closure during implementation, the NRRP has made clear the relevance of continuous performance monitoring on the one hand and the need to take into account the operational role of regions and local authorities (i.e., the levels on which operational decisions should get traction) on the other. In this regard, the head of the Department for European Policies announced in October 2023 the intention to strengthen the monitoring of local authorities, invoking the spending responsibility clause which foresees fines and costs of works to be borne by municipalities and regions that do not fulfill timely their commitments under the Plan.12 Only observing how the Plan's implementation will unfold over the next few years, however, will allow us to determine whether these moves represent a real change in the organizational design and functioning of the implementation arrangements, or simply reproduce the blame-shifting practices that have characterized center-periphery relations in Italy in recent decades.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Endnotes

Biographies

Fabrizio Di Mascio is Professor of Political Science at the University of Turin, Italy. His research focuses on public management reform, regulatory governance, anticorruption, and transparency. He has served as policy advisor to a number of Italian public bodies, including the Department for Public Administration, Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers.

Alessandro Natalini is Professor of Political Science at the LUMSA University of Rome, Italy. His research interests include public management reform, regulatory governance and cutback management. He has several years of professional practice experience in Italian public bodies, including the Department for Public Administration, Italian Presidency of the Council of Ministers.

Stefania Profeti is Associate Professor at the University of Bologna, Italy, where she teaches Public Policy Analysis, Governance and Public Policies, and Local Public Services. Her recent research focuses on multi-level governance, patterns of public-private relations and public policies, especially in the domain of local public services.