Inside Lobbying on the Regulation of New Plant Breeding Techniques in the European Union: Determinants of Venue Choices

Abstract

enIn July 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union decided that new plant breeding techniques (NPBTs) fall within the scope of the restrictive provisions on genetically modified organisms (GMOs). Previously, various actors had lobbied in order to influence the European Union’s (EU’s) regulatory decision on NPBTs. This study examines the venue choices taken by Cibus, a biotech company that promoted NPBT deregulation. It shows that the firm bypassed the EU level and that it lobbied competent authorities (CAs) in certain member states to gain support for the deregulation of NPBTs. Cibus chose the CAs because their institutional “closedness” reduced the risk of the debate over the deregulation of NPBTs becoming public. However, the CA’s specific competences and their influence on EU decision making were of likewise importance. The firm lobbied CAs based in Finland, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Two factors appear to have influenced Cibus’ choices for these countries: high-level political support for agribiotech and the high relevance of biotech sectors. In contrast, public support for GMOs turned out to have hardly any influence, and virtually no association could be observed for the agricultural application of biotechnology in the past nor for the weakness of domestic anti-GMO lobby groups. Finally, the in-depth study on Germany affirms that “closedness” was important for Cibus’ choices and reveals that technical information served as a venue-internal factor that influenced the firm’s choices.

Abstract

zh就新植物育种技术规制对欧盟进行内部游说:场地选择的决定因素

2018年6月,欧盟法院决定将新的植物育种技术(NPBTs)纳入转基因(GMOs)限制性条款。此前,不同行动者就此进行游说,以期影响欧盟对NPBTs的监管决策。本文检验了Cibus(一家提倡对NPBT放松管制的生物技术公司)的游说场地选择。事实表明,这家公司避开了欧盟的规制,并在部分成员国中对相关部门(CAs)进行游说,以期在NPBTs放松管制一事上获得支持。Cibus选择了CAs,因为后者的制度“封闭性”(closedness)降低了相关辩论被公开的风险。然而,CA的特定能力及其对欧盟决策产生的影响也具有同等的重要性。Cibus对芬兰、德国、爱尔兰、瑞典、西班牙和英国的相关部门进行了游说。两个因素似乎影响了Cibus对这些国家的选择:对农业生物技术的高度政治支持和生物技术部门的高度相关性。相反,公众对GMOs的支持几乎没有产生任何影响,并且不论是以往生物技术的农业文化应用或是国内反GMO游说团体的弱点,基本上都不存在任何联盟。最终,对德国的深度研究证实,“封闭性”对Cibus的选择至关重要,并且技术信息充当了一个对公司选择造成影响的内部场地因素。

Abstract

esCabildeo interno sobre la regulación de nuevas técnicas de fitomejoramiento en la Unión Europea: determinantes de lugares para eventos

En julio de 2018, el Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea decidió que las nuevas técnicas de fitomejoramiento (NPBT) están dentro del alcance de las disposiciones restrictivas sobre organismos genéticamente modificados (OGM). Anteriormente, varios actores habían cabildeado para influir en la decisión reguladora de la Unión Europea (UE) sobre NPBT. Este estudio examina las opciones de lugar tomadas por Cibus, una compañía de biotecnología que promovió la desregulación de NPBT. Muestra que la empresa pasó por alto el nivel de la UE y presionó a las autoridades competentes (CA) en ciertos estados miembros para obtener apoyo para la desregulación de las NPBT. Cibus eligió a las AC porque su "cerramiento" institucional redujo el riesgo del debate sobre la desregulación de las NPBT que se hacen públicas. Sin embargo, las competencias específicas de la AC y su influencia en la toma de decisiones de la UE fueron igualmente importantes. La firma presionó a las AC con sede en Finlandia, Alemania, Irlanda, Suecia, España y el Reino Unido. Dos factores parecen haber influido en las elecciones de Cibus para estos países: el apoyo político de alto nivel para la agrobiotecnología y la gran relevancia de los sectores biotecnológicos. En contraste, el apoyo público a los OGM resultó tener poca influencia, y prácticamente no se pudo observar ninguna asociación para la aplicación agrícola de la biotecnología en el pasado ni para la debilidad de los grupos de presión nacionales anti-OGM. Finalmente, el estudio en profundidad sobre Alemania afirma que la "cercanía" era importante para las elecciones de Cibus y revela que la información técnica sirvió como un factor interno del lugar que influyó en las elecciones de la empresa.

Introduction

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have been among the most controversial and unpopular policy issues in the European Union (EU) since the mid-1990s. Numerous actors at various political levels have been involved in the disputes raised by the topic of GMO field regulation (see e.g., Dobbs, 2016). In addition to policy makers, political parties, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and various associations, private companies also are committed to representing their (economic) interests (see e.g., Tosun & Schaub, 2017). However, while researchers investigated the lobbying activities of anti-GMO groups (see e.g., Bodiguel & Cardwell, 2010; Clancy & Clancy, 2016; Paarlberg, 2014; Schurman, 2004; Schurman & Munro, 2006), there is a considerable need for research into the lobbying activities of companies interested in agricultural biotechnology (agribiotech).

One of the main reasons for this research gap seems to be that biotech companies usually avoid campaigning publicly as GMOs are unpopular in many countries around the world, especially in the EU (see e.g., Herring & Paarlberg, 2016). Nevertheless, these actors are frequently presumed to pursue their interests by means of inside lobbying tactics, that is, through personal contacts with politicians or high-ranking bureaucrats behind closed doors (see e.g., Baumgartner & Jones, 2009). However, research has so far provided few empirical insights into such activities. One of the few studies to have done so comes from Lamphere and East (2017), who showed that Monsanto “consistently employed discursive resources that concealed details about actors and action, reflected trends among experts in global sustainability discourse, and reshaped narratives to promote itself, its products, and biotechnology in general.”

In addition, it became public in 2019 that a PR agency commissioned by Monsanto had collected data from critical journalists, politicians, and other stakeholders in several EU member states, mainly on their attitudes to the active component glyphosate prior to its reassessment by the EU in 2017 (Bayer, 2019). Since biotech companies reputedly tend to pursue their goals through inside lobbying tactics, there is room and need for further investigations in this field. One of the fundamental aspects in this respect concerns the venues, that is, certain institutional decision settings, in which these firms choose to promote their widely unpopular objectives.

To reduce the above-described research lacunae, this study investigates the venue choices made by U.S.-based Cibus in the EU multilevel system. Cibus aspired to market newly modified seeds to EU farmers even though EU institutions had not yet decided on whether products derived by “new plant breeding techniques” (NPBTs) were to be legally classified as GMOs or “traditionally” bred products (Jones, 2015). As this classification entailed far-reaching implications, Cibus attempted to influence the EU regulatory process on NPBTs in its favor.

In light of this, the following research question guides this study: Which venues did Cibus select to promote NPBT deregulation in the EU and which factors explain these selection decisions? Our first interest is which venues Cibus chose for the promotion of the unpopular issue of NPBT deregulation in the EU, whose multilevel polity provides advocates with multiple channels and targets for lobbying their objectives (Beyers & Kerremans, 2012; Princen & Kerremans, 2009). Second, we are interested in the factors which explain Cibus’ venue choices because previous research has revealed various venue-internal and -external factors accounting for advocates’ choices of venues (see e.g., Buffardi, Pekkanen, & Smith, 2015; Holyoke, Brown, & Henig, 2012; Ley, 2016; Ley & Weber, 2015; Marshall & Bernhagen, 2017; Pralle, 2003).

This study draws on the concept of venue shopping, which became widespread in the last two decades, especially for analyzing interest group politics (Baumgartner & Jones, 2009; Beyers, Donas, & Fraussen, 2015; Beyers & Kerremans, 2012; Buffardi et al., 2015; Huwyler, Tatham, & Blatter, 2018; Pralle, 2003). Based on various sources, it uses counterfactual reasoning to assess the importance of institutional “closedness” for Cibus’ venue choices as well as a comparative, factor-based approach to explain the firm’s choices for venues in certain EU member states. Finally, an in-depth study on Cibus’ activities in Germany in that field is conducted to produce more fine-grained information on the reasons for Cibus’ choices.

The results show that Cibus bypassed the EU level and chose national competent authorities (CAs), the key national bodies deciding on the legal classification of NPBT-modified crops, for its inside lobbying tactics. The firm chose the CAs because their institutional “closedness” promised to prevent debates on the unpopular topic of NPBT deregulation from becoming public. However, the company also did so because the CAs’ were able to produce regulatory opinions on NPBTs and influence EU decision making by cooperating with the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). The firm lobbied CAs, which were embedded in national contexts favorable to agribiotech, based in Finland, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom. Two factors appear to have influenced Cibus’ choices for these countries: high-level political support for agribiotech and the high relevance of biotech sectors. In contrast, public support for GMOs hardly had any influence, and virtually no association could be observed for the agricultural application of biotechnology in the past nor for the weakness of domestic anti-GMO lobby groups. Finally, the in-depth study on Germany affirms that “closedness” was important for Cibus’ choices and reveals that technical information served as an additional venue-internal factor that influenced the firm’s choices.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The second section provides an overview of the EU regulatory process on NPBTs, laying the groundwork for the empirical analysis. Next, the theoretical framework is introduced. After presenting the database and the methodical approach, the empirical analysis is executed in three steps. First, it assesses whether institutional “closedness” influenced Cibus’ venue choices, then the institutional channel that the firm used to influence regulatory decision making on NPBTs at the EU level is delineated. Second, it comparatively examines the reasons for Cibus’ decision to lobby CAs in certain member states and not in others. Third, the case study is used to investigate further factors that influenced Cibus’ choices. The article ends with some concluding remarks.

The EU Regulatory Process

The European Commission made several attempts to agree on a regulatory approach toward NPBTs in the last decade. The authority started dealing with the issue in 2007 when it established a “New Techniques Working Group” in order “to analyse a nonexhaustive list of techniques for which it is unclear whether they would result in a GMO” and “whether the resulting products fall under the scope of the existing GMO […] legislation” (European Commission, 2011, pp. 1–2). The group defined the term “New Plant Breeding Technology” to designate eight new breeding techniques.1 They evaluated them in the light of Directive 2001/18/EC, which defines a GMO as “an organism/micro-organism […] in which the genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally by mating and/or natural recombination.” The EU’s original GMO definition dates to the initial establishment of the EU regulatory framework as prescribed by Directive 90/220/EEC. Four years later, however, experts arrived at differing legal interpretations of the techniques, though most breeding tools were deemed not to produce GMOs (European Commission, 2011).

The European Commission also mandated the “Joint Research Centre,” its scientific service agency, to assess the economic relevance of new breeding techniques. Its report was published in 2009. The scientific experts focused on the same eight techniques as evaluated by the beforementioned working group and investigated their status of research development of the adoption of NPBTs by the breeding sector, the potential development of commercial products, and the challenges of detecting resulting products. The report states that the level of development of new breeding techniques varies considerably and that, besides technical advantages, several challenges, of which consumer acceptance and regulatory aspects are the most important, exist for the commercialization of resulting products in the EU (Lusser, Parisi, Plan, & Rodriguez Cerezo, 2011).

Moreover, the European Commission requested the EFSA to deliver a scientific opinion on plants developed through two new breeding tools (cisgenesis and intragenesis). EFSA concluded that the existing guidance for the risk assessment of GM plants (food and feed and environment) was applicable also for the evaluation of plants derived by these techniques and that there was no need to develop the existing guidance (EFSA, 2012, p. 2). Moreover, EFSA compared the hazards associated with plants developed by the two techniques with those obtained by “conventional” breeding or by genetic engineering (transgenesis). It concluded that “similar hazards can be associated with cisgenic and conventionally bred plants, while novel hazards can be associated with intragenic and transgenic plants” (EFSA, 2012). Since “unintended changes” might occur through various breeding techniques, EFSA suggested a case-by-case-based risk assessment for products derived by new breeding tools.

In 2015, the European Commission called upon the so-called “High Level Group,” a scientific advisory board on the EU level, to compile a report on new breeding techniques. According to the report, which was published in 2017, new breeding tools offer various benefits. Among these is the reduced risk of unintended effects, since these new tools are more precise than their “conventional” counterparts. Moreover, the board recommended in line with EFSA that safety assessments for newly modified products should be based on case-by-case assessments (European Commission, 2017).

It took more than a decade until the EU provided the member states with regulatory guidance on NPBTs. In July 2018, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) ruled that these “genome editing” techniques should be legally classified as genetic engineering techniques, wherefore resulting products fall under Directive 2001/18/EC (CJEU, 2018). The phase preceding the final regulatory decision, when plant scientists increasingly applied NPBTs, represented a crucial period for lobbying activities.

Theoretical Framework

This study draws on the concept of venue shopping, which originally relates to advocates who face obstacles in certain decision settings and therefore look out for other ones, which they consider more promising for the promotion of their policy objectives (Baumgartner & Jones, 2009, p. 36). Recently, scientific attention surrounding advocates’ decision to select certain venues has increased; scholars refer to this as venue choice (Huwyler et al., 2018; Ley, 2016; Ley & Weber, 2015; Marshall & Bernhagen, 2017). This study concentrates on the factors that influenced Cibus’ venue choices when this firm looked out for the most suitable decision settings for promoting NPBT deregulation in the EU multilevel system.

Unpopular Policies and Institutionally Closed Venues

Baumgartner and Jones (2009, p. 36) have argued that some venue shoppers attempt to realize their policy objectives by inciting policy conflicts as this generates public attention and mobilization (“image manipulation”), while others practice inside lobbying tactics based on personal contact with politicians and high-ranked bureaucrats. The central variable determining which of these two fundamentally diverging strategies advocates opt for essentially relates to policy objectives. Hence, it seems expedient to distinguish whether their pursued policy goals are popular or unpopular in certain societal/political spheres.

When advocates strive for popular policy objectives, which most citizens and the media welcome, they can use these headwinds to assert themselves in public discourses and accomplish their policy goals. However, when advocates seek widely unpopular policy objectives, they will struggle to assert themselves in public discourses because their policy opponents are backed by the major population and the media. To increase their chances of achieving their unpopular policy objectives despite this disadvantage, advocates make use of certain strategies. Weaver (1986) noted in his seminal work that political actors employ certain “blame-avoidance” strategies to reduce the risk of potential political losses when pursuing unpopular policy reforms because voters tend to be more sensitive to real or potential losses than to gains (see e.g., Hinterleitner, 2017; Hood, 2011; Hood, Jennings, & Copeland, 2016). The domain of social policy reform in particular has investigated these strategies, analyzing which specific strategies political advocates opt for and why (Vis, 2015). Nevertheless, this lens of blame avoidance also has been applied to other policy domains, researching, for example, governments’ use of strategic communication for justifying the liberalization of national GMO regulatory frameworks (Wenzelburger & König, 2017).

At first glance, it appears that Cibus could have attempted to realize its objective of deregulating NPBT by mobilizing the public. After all, EU citizens are generally unfamiliar with the NPBT topic, meaning that framing strategies, for instance, could be successful. However, the decade-long struggle over GMOs has indicated that topical unfamiliarity, in combination with negative public bias, results in the instinctive rejection of technological innovations (Legge & Durant, 2010). In addition, the GMO case has shown that anti-GMO groups have been exploiting the topic since the mid-1990s to shape anti-GMO public sentiment (see e.g., Clancy & Clancy, 2016). This, in turn, has induced policy makers in several member states to abandon supporting GMOs and instead advocate stricter regulations (see e.g., Schurman & Munro, 2006). Accordingly, we have reason to assume that the strategic calculations underlying Cibus’ venue choices will differ from those of venue shoppers seeking popular policy objectives. Consequently, we can infer from this that the company should not have incentives to choose venues that generate public attention and mobilization. Rather, we expect Cibus to opt for those venues, which facilitate its pursuit of NPBT deregulation behind closed doors.

Research has shown that venues differ from each other institutionally in many ways and that advocates take features such as internal rules, decision-making procedures, and institutional actors into account before choosing in which venues to pursue their policy objectives (Constantelos, 2010; Holyoke et al., 2012; Huwyler et al., 2018; Ley, 2016; Ley & Weber, 2015; Marshall & Bernhagen, 2017). In light of this, the first major argument of this article is that Cibus will choose venues that are characterized by institutional “closedness.”

Institutionally “closed” venues can be conceived as decision-making arenas that inhibit participation. For instance, participation can be confined to small sets of actors comprising, as a minimum, the venue shopper himself and the venue decision maker. Hence, the public, the media, and policy opponents have no or only limited access to such “closed” venues. This implies that institutional closedness limits the possibilities of external actors to interfere in venue-internal processes and to influence the judgments of venue decision makers. However, it also means that advocates of unpopular policy objectives can better anticipate the probable outcomes of their access to such venues. Furthermore, limited participation reduces the transparency of venue-internal processes, meaning that social debates are unlikely to emerge, even though unpopular policy options might be at stake. This further raises the likelihood of advocates realizing unpopular policy goals. For example, bureaucratic authorities are more closed than, say, legislative bodies, in which internal processes are more easily influenced by the public or policy opponents.

Taken together, this paper argues that Cibus will choose venues characterized by institutional closedness for their promotion of NPBT deregulation since these reduce the risk of sparking public debates, which could ultimately threaten their chances of success.

Venue Decision Makers and Venue Contexts

Research has shown that venue shoppers take several venue-related factors into account before making their choices (see e.g., Buffardi et al., 2015; Holyoke et al., 2012; Ley, 2016; Ley & Weber, 2015; Marshall & Bernhagen, 2017; Pralle, 2003). Nevertheless, venue decision makers ultimately represent the key actors, who determine whether their activities will be successful. Holyoke and colleagues (2012) have shown that policy advocates assess their congruence with venue decision makers regarding mutual policy preferences and ideological stances before making their venue choices. This information is crucial for venue shoppers as it is the most revealing indicator of how successful their lobbying in a particular venue is likely to be.

However, advocates often lack the necessary information concerning venue decision makers, for instance, when no working contacts previously existed or when advocates access multiple venues to promote their policy goals (“venue diversification”; Baumgartner & Jones, 2009). When advocates lack information on how venue decision makers will most probably decide on certain issues, on which parameters will the venue shoppers base their venue choices? Ley and Weber (2015) indicated that venue shoppers choose venues by strategically assessing venue contexts. This argument aligns well with one central premise of behavioral theory, which states that societal contexts shape humans’ attitudes, standpoints, and decisions (see e.g., Larrick, 2016). On this theoretical ground, we presume that advocates, who look out for the most promising venues to promote their objectives but lack information on venue decision makers, will strategically consider venue contexts, since these shape the judgments of venue decision makers.

Assessing venue contexts should be less promising when issues are uncontroversial and scientifically certain as, in these cases, decision makers will guide their judgments using certain standard procedures. However, consideration of venue context should be expedient for advocates pursuing cutting-edge projects, since these entail scientific uncertainty and decision ambiguity (see, e.g., Florin, 2014). For example, certain member states invoked the precautionary principle for dealing with the uncertain risks arising from GMOs, while others did not (Tosun, 2013). In this light, we assume that, when dealing with scientifically uncertain/ambiguous policy issues, venue contexts may critically influence the judgments of venue decision makers. Generally, this reasoning should apply to almost all venues, because ultimately venue decision makers make formal decisions. Florin (2014), for instance, has shown that bureaucratic agencies do not necessarily guide their decisions by following certain standard procedures that have been provided by scientific evidence; rather, even scientific bodies are responsive to societal or political pressures/demands.

NPBTs represent an ambiguous and scientifically uncertain issue, which is why regulatory decision making on this topic is cutting edge. In other words, regulators may arrive at different assessments of these new breeding tools. There is reason to expect that certain contextual factors may crucially influence venue decision makers’ judgments on whether NPBTs should be regulated under the provisions already in place for GMOs. We therefore expect Cibus to choose venues located in contexts that are favorable to NPBT deregulation.

Reasons for Cibus’ Venue Choices

The first contextual factor that we expect to favor NPBT deregulation, and which might have influenced Cibus’ venue choices, relates to the application of agribiotech in domestic agriculture in the past. When farmers could plant GM crops or, put differently, where legislators did not prohibit them from doing so (even though appropriate legal possibilities existed), agribiotech served as a part of agricultural production. For this reason, future applications of NPBTs should be more likely in these countries. Accordingly, Cibus can be expected to choose venues in member states in which GMO farming took place since venue decision makers should always consider the future relevance of agribiotech, for example, to the agricultural productivity and competitiveness of a country and therefore decide in favor of NPBT deregulation.

The second factor of importance for this analysis is public support for agribiotech. Venue decision makers are necessarily part of their respective societies, and collective attitudes on policy issues rub off on those of individual actors. So, if a national public is generally positive toward agribiotech, venue decision makers in this country should also view this issue generally positively and voice regulatory opinions in favor of NPBTs. Given that venue decision makers are influenced by public sentiment on policy issues, we expect Cibus to choose venues located in member states in which most citizens are open to agribiotech.

The third factor that we expect to influence Cibus’ choices is political support for agribiotech. Governments usually have a leadership role vis-à-vis subordinate authorities. Hence, in countries where leading politicians are positive toward agribiotech, their top-down instructions are likely to materialize in venue decision makers deciding in favor of NPBT deregulation. If agribiotech is supported at high political levels in a member state, this should increase Cibus’ willingness to select a venue for inside lobbying in this country.

The fourth factor relates to the economic relevance of domestic biotech sectors. National key industries can have a strong influence on the decisions of venue decision makers as they often have long-standing working relationships with agency employees. Given that the operations of venue decision makers are influenced by the importance of certain industry sectors, we expect Cibus to choose venues in member states that have strong biotech industries.

The fifth factor important for this study relates to domestic anti-GMO lobby groups. These groups, among others, consist of NGOs as well as environmental, agricultural, and consumer associations and have mobilized against GMOs in many member states, compelling policy makers on different levels to enact stricter regulations (see e.g., Paarlberg, 2014). Even though these groups have limited access to institutionally closed venues, they may interfere in venue-internal processes by attracting public attention toward the unpopular topic of NBPTs and by mobilizing against it, which could ultimately result in venue decision makers choosing to regulate NPBTs. Accordingly, we expect Cibus to select venues in those countries in which anti-GMO groups are weak.

In sum, we expect Cibus to choose venues in member states in which: (1) agribiotech has been relevant in agricultural production, (2) the public is relatively open to agribiotech, (3) agribiotech is supported at high political levels, (4) biotech industries are powerful, and (5) anti-GMO groups are weak.

Clarifications on Data and Methods

The dependent variable of this study, CA Accessed, is binary and takes the value 1 for those member states in which CAs received Cibus’ requests for scientific field trials with its NPBT-modified canola as prescribed by the EU’s authorization procedure for the experimental release of GMOs into the environment (European Commission, 2018). There are two main reasons why Cibus used requests for scientific field trials to influence the EU regulatory process on NPBTs.2

To assess whether the feature of institutional “closedness” influenced Cibus’ venue choices, we discuss the “closedness”/“openness” of several venues that the EU multilevel system provides and that the firm could have lobbied. Based on counterfactual reasoning, we examine whether it is plausible that this factor affected Cibus’ venue choices. Accordingly, the data were gathered by means of Internet research on biotech lobbying and from previous research on venue shopping in the EU multilevel system.

To examine the effects of the factors specified in the previous section, we used different measurements. Generally, all indicators are not older than 2014, which is important because Cibus performed its lobbying activities from 2011 to 2014. For methodical reasons, all indicators which were not already binarily were coded in this way. (Table 3 will present the indicators for all EU member states.)

First, the indicator of GMO farming is used to assess whether the past application of agribiotech in domestic agricultures has influenced Cibus’ choice. The indicator reports whether GM crops were ever cultivated commercially in a member state. The data were taken from the annual report of the U.S. Department of Agriculture on agribiotech in the 28 EU member states (USDA Foreign Agricultural Service, 2015). Second, to measure the public support for GMOs in the member states, we used the result of the question of the 2010 Special Eurobarometer on Biotechnology, which asked the respondents whether they agreed or disagreed that the development of GM foods should be encouraged (European Commission, 2010). To make the indicator Public GMO-support binary, we calculated the average for all member states (25.96%), then separated the countries against this threshold.

Using data on the voting behavior of national governments on the authorization of new GM products in the Council of the European Union, we examine whether it affects Cibus’ venue choices (Council Voting). If governments voted more often “Yes” or “Abstention” than “No,” they can be assumed to support NPBT deregulation. In addition, we combined the “Yes” and “Abstention” votes, since the latter is usually considered a softer form of approval as abstentions prevent the Council from reaching qualified majorities, thereby prevent the authorization of GM products. The data on this variable were taken from Mühlböck and Tosun (2015).

The fourth indicator refers to the economic relevance of domestic biotech sectors and indicates whether or not a member state has a leading biotech industry. The data for the variable Strong biotech industry were taken from Cooper (2009, p. 537). Finally, to determine whether anti-GMO groups are influential—the fifth factor—we used the indicator Weak Anti-GMO Lobby, which indicates in binary fashion whether or not the environmental NGO “Friends of the Earth” operates in a member state. We used this indicator as research has shown that this NGO, in particular, functioned as the key actor of GMO resistance in several member states (Seifert, 2012, p. 218). Since data on anti-GMO groups in the EU-28 were not available, we asked Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace for member data, but unfortunately, we did not receive it. Therefore, we took data for this variable from the Friends of the Earth (2014) Europe Annual Review.

Based on the five binary indicators, we created a crosstab and calculated Cramér's V to explain Cibus’ venue choices comparatively (see Table 2). Cramér's V is a contingency coefficient that lies between 0 and 1. It is a measure of the strength of the relationship between two nominally scaled variables if at least one of the two variables has more than two values. If Cramér’s V = 0, then no association exists between two variables; if Cramér’s V = 1, a perfect connection exists between the variables (Cramér's V = 0.1–0.3: weak association; 0.4–0.5 middle association; >0.5 strong association).

Finally, to explore Cibus’ venue choice for Germany, several primary data sources were used, including official documents, position papers, legal opinions, and scientific reports. In addition, partly redacted confidential communication between Cibus and the German CA were consulted. These data were obtained by German NGOs by means of a freedom of information request and can be accessed in the online appendix. Last, we complemented the database for the case study by drawing on insights from Corporate Europe Observatory (2016) and Sprink, Eriksson, Schiemann, and Hartung (2016).

Empirical Analysis

Cibus considers itself the “world leader in advanced breeding technologies, generally, and advanced non-transgenic (non-genetic engineering) breeding, specifically” (Cibus, 2018). The company employs a breeding technique called “rapid trait development system,” which, it claims, facilitates nongenetic engineering plant breeding. Using this breeding tool, the company developed several plants: herbicide tolerant canola, glyphosate tolerant flax, herbicide-tolerant rice, and potato resistant to Phytophthora (Cibus, 2018). However, none of these products have been commercialized in the EU yet—unlike in other countries, including the United States and Canada (The Western Producer, 2016).

Assessing the Effect of Institutional Closedness on Cibus’ Choices

As indicated above, the fundamental competences for the regulation of NPBTs reside at the EU level, where the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, the European Council, the European Parliament, the CJEU, the EFSA, as well as the various subdivisions of these bodies, such as the Directorate-Generals in the European Commission, all represent possible venues that Cibus could have accessed (Beyers & Kerremans, 2012). Most of these venues, except for the European Parliament, are rather closed in institutional terms, for which reason one might think that they offered promising venues for Cibus' aspirations.3 However, lobbying these venues would not have guaranteed success for the company, because EU institutions have failed for about a decade to establish an NPBT regulatory approach, as indicated above. Hence, it is highly plausible that the persistent EU regulatory gridlock on NPBTs compelled Cibus to make use of the multilevel system and look out for promising venues for their promotion of NPBT deregulation at the member state level. Consequently, Cibus selected national CAs for its lobbying strategy.

The CAs are staffed with appointed and career professionals and are designed to concentrate their scientific and technical expertise on tasks ranging from food, animal feed, consumer products, pesticides, and veterinary drugs to GMOs. The national agencies work closely together within the network on GMO risk assessment, which allows them to share information, expertise, and practices among each other and particularly with EFSA (European Food Safety Authority, 2018). Both the CA-internal processes as well as their operations within expert networks take place behind closed doors. Usually, the agencies only publish their final assessments and press releases, and internal processes are generally not accessible to the public. Therefore, external actors have extremely limited possibilities to intervene in either the internal or network-based processes of the CAs.

For this reason, it seems plausible that Cibus selected the CAs because of their institutional closedness. The company could be certain that social debates and policy conflicts would be unlikely to emerge from their accessing of these venues, which consequently increased its likelihood of success. Nevertheless, we cannot provide sufficient evidence at this point that Cibus’ venue choices were in fact primarily affected by the feature of closedness, since two other factors are also likely to have influenced its choices.

The first of these concerns the necessary competences of venue decision makers to assess whether NPBT-modified crops represent GMOs. This decision is such a complex one that many venue decision makers, such as politicians, cannot even answer it competently at all. However, the CA professionals have the scientific and technical expertise to classify NPBTs on scientifically sound bases. The second factor relates to the fact that the basic regulatory decisions on NPBTs are taken at the EU level and not at national or regional levels. Hence, Cibus could, for instance, have lobbied competent ministries, such as those for agriculture or certain expert commissions. However, this would not have been expedient for them, for the influence of these venues on the NPBT regulatory process at the EU level, even though it may be present, is generally unclear. The CAs can, however, use the institutionalized cooperation bodies with EFSA to exert influence over the regulatory assessment of biotechnology products (see below).

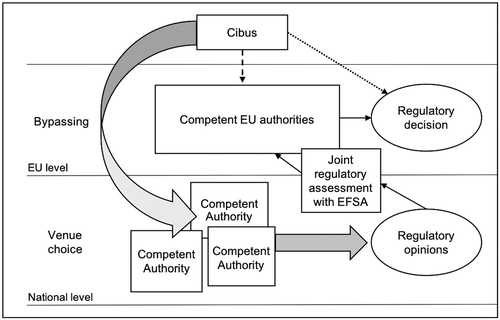

The opportunity structure, as well as the way Cibus aimed to influence the EU regulatory process on NPBTs, is schematized in Figure 1. Cibus made use of two institutional procedures as defined by EU law. The first one is the authorization procedure for experimental GMO releases carried out by national agencies in the member states, namely CAs. The second procedure is the institutionalized cooperation of these national bodies with EFSA in the regulatory assessment of biotechnology products.

The authorization procedure for the experimental release of GMOs into the environment requires that a “person or a company […] first obtain written authorisation by the competent national authority of the [m]ember [s]tate within whose territory the experimental release is to take place” (European Commission, 2018). Usually, when a CA has to decide on a request for an experimental release, it bases its decision on an evaluation of the risks to the environment and human health presented by the GM crop (Directive 2001/18/EC). The European Commission (2018) denominates such an authorization process as a “purely national procedure as it is only applicable in the [m]ember state where the notification was submitted.”

However, Cibus did not request the CAs for scientific releases of GM crops, which would have triggered the standard procedure commonly applied for years. Rather, the company requested the bodies for scientific releases of a crop modified by its new breeding technique (rapid trait development system). Hence, the request denoted a completely new challenge for the CAs, which had to evaluate whether they considered the crop a GMO. Only after these assessments could they decide on the release of the Cibus’ modified canola. Of course, the firm could have performed this lobbying strategy during the phase of NPBT regulatory gridlock at the EU level, as indicated above.

In the second procedure, the CAs cooperate with EFSA in the regulatory assessment of biotechnology products. EFSA is the key player for scientific advice on and risk assessment of food products developed by agricultural biotechnology at the EU level (Paoletti et al., 2008). While EFSA provides scientific information, the decision making on the authorization, inspection, and control of products is the responsibility of the risk managers, namely the European Commission and the individual member states. Although the member states mainly function as risk managers, at least two channels exist by means of which national decisions can influence regulatory activities at the EU level.

First, the CAs can influence GMO assessments conducted by the EFSA. They do this by issuing opinions on EFSA safety assessments when GM products are to be cultivated or processed commercially. EFSA consults the CAs on every GMO application and provides feedback to their scientific concerns during the risk assessment process (Paoletti et al., 2008, p. 71). Second, national bodies can promote their views by means of information and expertise exchange as well as by best practices within a joint network, in which they work together with EFSA on certain projects on GMO risk assessment (EFSA, 2018).

Taken together, there is reason to assume that Cibus’ venue choices were indeed influenced by the feature of institutional closedness. Nevertheless, apparently, two other factors also motivated Cibus to choose the national CAs: their specific competence for classifying NPBTs, and their privileged ability to influence EU regulatory decision making via EFSA. Since the CAs were institutionally closed, capable to assess NPBTs in regulatory terms, and could, at least in principle, influence EFSA opinions, they represented favorable venues for Cibus’ lobbying aspirations. Nevertheless, our results on institutional closedness are not entirely clear, which is why we further examine the relevance of this aspect in the in-depth study on Germany.

Comparative Explanation of Cibus’ Venue Choices

When Cibus started filing requests for field experiments in 2011, the firm lacked information regarding how the CAs would classify NPBTs in regulatory terms, for these bodies had scarcely dealt with the issue of NPBT regulation. After all, NPBTs only started to be developed during the mid-2000s, and for years no commercially relevant applications existed that would have activated the CAs to deal with this issue.4 Due to this lack of information, Cibus presumably had strong incentives to consider certain contextual factors in their assessment of how successful they were likely to be when lobbying CAs in particular member states.

Table 1 shows that Cibus chose CAs in six EU member states, namely Finland, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom in order to provide regulatory opinions on its NPBT-modified canola. Even though it is not the focus of this study, the company’s success in this regard should be noted as each of the CAs came to the opinion that the crop should not be regulated as a GMO.5 Can these—from Cibus’ point of view, successful—venue choices be in terms of the indicators introduced above?

| Member State | Competent Authority | Regulatory Opinion |

|---|---|---|

| Finland | Finnish Board of Gene Technology | Non-GE |

| Germany | Federal Office of Consumer Protection and Food Safety | Non-GE |

| Ireland | Food Safety Authority of Ireland | Non-GE |

| Spain | Interministerial Council for GMOs | Non-GE |

| Sweden | Swedish Board of Agriculture | Non-GE |

| The United Kingdom | Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | Non-GE |

Table 2 presents the results of a crosstab of the 28 EU countries, separated into “CA Accessed” and “Other Member States”—that is, those which have not received a request for field trials by Cibus. In addition, the crosstab encompasses the five indicators introduced for calculating the associations for each of them separately. The following interpretation of the results can be easily comprehended by using the overview of the member states and the indicators given by Table 3.

| CA Accessed (6 MS) | Other Member States (22 MS) | Cramér’s V (P-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GMO farming | 33.3% (2 MS) | 27.27% (6 MS) | 0.0535 (.8231) |

| Public opinion | 83.33% (5 MS) | 45.45% (10 MS) | 0.3117 (.2351) |

| Council votinga | 100% (6 MS) | 33.33% (7 MS) | 0.5548 (.0156) |

| Strong biotech industry | 66.66% (4 MS) | 9.09% (2 MS) | 0.5757 (.0129) |

| Weak anti-GMO lobby | 16.66% (1 MS) | 22.73% (5 MS) | 0.0598 (.8065) |

- a Bulgaria was excluded from the analysis.

| Member State (* CA Accessed) | GMO Farming | Public Opinion | Council Voting | Strong Biotech Industry | Weak Anti-GMO Lobby | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Austria | |||||

| 2 | Belgium | X | X | |||

| 3 | Bulgaria | – | ||||

| 4 | Croatia | |||||

| 5 | Cyprus | |||||

| 6 | The Czech Republic | X | X | X | ||

| 7 | Denmark | X | ||||

| 8 | Estonia | X | X | |||

| 9 | Finland* | X | X | X | ||

| 10 | France | X | X | X | ||

| 11 | Germany* | X | X | X | ||

| 12 | Greece | X | ||||

| 13 | Hungary | X | ||||

| 14 | Ireland* | X | X | |||

| 15 | Italy | X | ||||

| 16 | Latvia | |||||

| 17 | Lithuania | |||||

| 18 | Luxembourg | |||||

| 19 | Malta | X | ||||

| 20 | The Netherlands | X | X | X | ||

| 21 | Poland | X | X | |||

| 22 | Portugal | X | X | X | ||

| 23 | Romania | X | X | |||

| 24 | Slovakia | X | X | X | ||

| 25 | Slovenia | X | X | |||

| 26 | Spain* | X | X | X | ||

| 27 | Sweden* | X | X | X | ||

| 28 | The United Kingdom* | X | X | X | X |

Note:

- Bulgaria voted each once with “Yes” and “No” in the Council.

The calculation of Cramér’s V in Table 2 shows that no association exists between GMO Farming and Cibus’ venue choices. The company filed requests to only two of the six countries in which GMO cultivation took place, namely Germany and Spain (33.3%). However, GMO farming was of minor importance in Germany until it was banned in 2009 (Cooper, 2009). Only in Spain, where the EU-wide most liberal GMO regulatory framework exists, does GM maize continue to be an important economic factor. Remarkably, the firm also targeted Finland, Ireland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, even though farmers have never cultivated GM crops for commercial purposes in these countries (Table 3). Furthermore, farmers also planted GM crops in six member states, whose CAs did not receive requests from Cibus (27.27%): the Czech Republic, France, Poland, Portugal, Romania, and Slovakia.

The computation of Cramér’s V indicates a weak relationship between those countries which Cibus targeted and public support for agribiotech (Public Opinion). The firm lobbied Ireland, Finland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom (83.33%)—all countries, whose populations view agribiotech relatively positive (Table 3). Of the six countries accessed, only in Germany was public opinion below the average of all the member states. The publics in Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Slovakia also consider agribiotech relatively positive (Table 3; 45.45%); however, Cibus did not file requests to those countries’ CAs.

Cramér’s V shows a strong association for Council Voting. In other words, all countries in which CAs were requested by Cibus voted in favor of the authorization of new GM products in the Council of the European Union (100%). This pattern even includes Germany, which often abstained from such votes due to interministerial disagreement (see above). Remarkably, seven other countries—Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Netherlands, Slovakia, and Slovenia—also voted mostly in favor of new authorizations in the Council (33.33%); however, none of their CAs received Cibus’ requests.

Table 2 also shows a strong association for Strong Biotech Industry. Of the countries with powerful biotech industries, Finland, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom have been lobbied by the firm (66.66%). While France and the Netherlands, the other two member states with powerful biotech sectors, were not lobbied by Cibus (9.09%), Ireland and Spain received requests for field experiments with the modified canola, even though they have no major biotech industries (Table 3).

Finally, Table 2 shows that no association exists between the indicator Weak Anti-GMO Lobby and Cibus’ venue choices. Of the member states lobbied by the firm, only the United Kingdom has a noninfluential anti-GMO lobby (16.66%). The other member states with weak anti-GMO lobbies are Greece, Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Slovenia (Table 3, 22.73%). From our point of view, the indicator employed for this variable seems rather reliable for Portugal, Romania, and Slovenia; however, it does not appear to fit with Greece and Italy since these two countries have relevant anti-GMO lobbies, which mostly come from the agricultural sector and defend the economic interests of organic and conventional food production chains.

Taking the observations together, two factors can be observed that appear to have influenced Cibus’ choices for CAs in certain member states: high-level political support for agribiotech (Council Voting) and the high relevance of biotech sectors (Strong Biotech Industry). Values for Cramér’s V for these main explanatory factors are statistically significant at the 5% level, which further strengthens our results, especially when considering the low number of cases (p values: .0156; .0129). Public support for GMOs (Public Opinion) turned out to have minimal influence. The relationship is also not statistically significant. It should be noted, however, that, due to the small number of cases, weak associations are less likely to be statistically significant in general. Virtually no association could be observed for the agricultural application of biotechnology in the past (GMO Farming) nor for the weakness of domestic anti-GMO lobby groups (Weak Anti-GMO Lobby).

The varying associations can also be seen in cases that arguably provide relatively unfavorable contexts for Cibus’ objective of NPBT deregulation. For instance, Table 3 indicates that GM crops have never been cultivated commercially in Ireland, that the Irish biotech industry is not particularly powerful, and that anti-GMO lobbies exist in this country. Nevertheless, Cibus’ lobbied the country, presumably because Irish governments strongly supported GMOs.

Based on these findings, it is also worth considering the countries that were not selected by Cibus, since several interesting patterns can be observed. According to Table 3, the Czech Republic and Slovakia in particular would have represented rather favorable contexts for Cibus’ venue strategy. In both countries, farmers commercially cultivated GM crops, the public was relatively positive regarding GMOs, and governments mostly voted in favor of new GM products. However, since the factor of strong biotech industries appears to have had a rather strong influence on Cibus’ venue choices, Cibus might have been motivated to leave these two countries out of its lobbying strategy since neither of them have especially strong biotech sectors.

Furthermore, interesting patterns exist regarding a large group of countries to which Cibus also filed no requests. Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, and Luxembourg all represent countries that are characterized by overtly unfavorable contexts in terms of the indicators (Table 3). The fact that no CAs in these countries were chosen by Cibus generally substantiates our empirical observations above. Finally, there is another group of countries that is characterized by rather favorable contexts for NPBT deregulation, which, however, have also not been lobbied by the firm. This group consists of Belgium, Estonia, France, the Netherlands, Poland, and Portugal (Table 3).

Overall, we find empirical support for the reasoning that Cibus selected CAs in member states where agribiotech is supported politically at high levels and where strong biotech industries exist. It becomes even clearer that Cibus made their venue choices for strategic reasons, when considering also those member states whose CAs were not accessed by the company. Next, the case of Germany is investigated in order to reflect both the relevance of institutional closedness and certain venue-external factors. In addition, the case study serves to explore venue-internal factors that might have influenced Cibus’ venue choices.

Explaining Cibus’ Choice of Germany

the evaluation of your request by the BVL will not include any participation or active information of the public or involvement of other authorities. We will probably ask our national expert committee (ZKBS [Central Commission for Biological Safety]) for an opinion on the request.

This statement indicates that the BVL was aware of how important it was for Cibus that the proceedings take place behind closed doors. Therefore, even the German CA’s awareness that Perseus wanted the regulatory assessment to be dealt with away from other stakeholders and the public supports our above reasoning regarding institutional closedness.

Technical Information and Personal Contacts

In fact, the BVL mandated the ZKBS to be the evaluation authority. This advisory body should now assess whether the modified canola falls into the scope of the German genetic engineering law, which reflects the GMO definition included in Directive 2001/18/EC. What is important here is that the ZKBS had already published a position paper on NPBTs in 2012. Therein, the experts concluded that most NPBT-modified products, including such produced by Cibus, should not be considered and regulated as GMOs (BVL, 2012). In fact, the committee, upon the BVL’s mandate and in line with its previous opinion, classified Cibus’ canola as non-GMO (ZKBS, 2015). Does this opinion represent a unpredictable, fortunate decision for Cibus or did its consultant, Perseus, know about how ZKBS would classify the crop?

Apparently, the latter holds true. In the request for the field trials sent to the CAs, Perseus, among many other things, refers to the ZKBS’s 2012 regulatory opinion (Perseus, 2014). Most importantly, Perseus states therein that the ZKBS concluded that “organisms which have been generated using the ODM (Oligo Directed Mutagenesis) technique are not GMOs” (Perseus, 2014, p. 9). To make this clear: it is scientifically widely undisputed that the breeding technique employed by Cibus to modify the canola (rapid trait development system) represents one variant of ODM. Interestingly, Perseus, in its request for field trials, also refered to the regulatory opinions from two other CAs that received requests—the UK DEFRA and the Swedish Board of Agriculture, which had also concluded that the canola would not fall in the scope of their respective national GMO legislations (Perseus, 2014, p. 8).

Hence, it can be concluded that Perseus was aware that the BVL would mandate the ZKBS to evaluate Cibus’ canola. On this ground, the consultant apparently anticipated the BVL’s regulatory opinion. Ultimately, in early 2015, Cibus received the response from the German CA Perseus had anticipated. In fact, the BVL stated that the canola would not be considered a GMO in Germany, wherefore it would be deregulated, which means that field trials with the crop could be conducted without regulatory oversight (BVL, 2015a).

Since personal contacts lie at the center of theoretical considerations on inside lobbying tactics, we also attempted to empirically investigate a possible influence of such relationships between the lobbyist (Perseus/Cibus) and the venue decision maker (BVL) on Cibus’ venue choices. Therefore, we asked several actors for interviews; however, unfortunately, we could interview only one expert as the others have not responded to our requests. The anonymous expert did not want to comment on possible personal contacts, however, according to the expert, a personal relationship appeared as not being decisive for Cibus to request the BVL. Instead, the interviewee pointed out that it would have been much more important that the outcome of the inquiry to the BVL had been open in principle, which means that the BVL could have assessed Cibus’ rape as a GMO but also as a non-GMO. This is remarkable, as it corresponds with our above observation regarding the relevance of the ZKBS (2012) regulatory opinion.

Nonetheless, to shed at least some light on whether personal contacts influenced Cibus’ venue choices we again consulted the e-mail correspondence between Perseus and the BVL. The e-mails at least suggest that personal contacts between both sides might have existed. The fact that the leading officials of Perseus and the BVL addressed each other by their forenames in the e-mails at least points in that direction, especially when considering that, in Germany, people usually use their forenames if a personal relationship exists. Although this observation might indicate a personal relationship, it is far from being sufficient enough to draw any conclusion regarding whether this influenced Cibus to choose the BVL for its lobbying strategy.

In sum, one venue-internal factor appears to have influenced Cibus’ choice for the German CA, namely the “technical information” published by the ZKBS in 2012. Since Perseus apparently knew the bureaucratic procedure, according to which the BVL usually relies on ZKBS opinions in such cases, the firm could be confident that lobbying the BVL would be successful.

Anti-GMO Groups

Finally, the German case illustrates the relevance of anti-GMO groups, a venue-external factor that we viewed as being of minor importance for the venue choices taken by Cibus above. First of all, Germany diverges significantly from the other five countries that were lobbied because it is the only one in which the CAs’ decision to deregulate Cibus’ canola sparked strong resistance of an anti-GMO coalition. In Germany, this coalition consisted of various environmental, agricultural, and consumer associations. Responding to the BVL’s deregulatory decision, the anti-GMO coalition legally contested it in March 2015. The coalition stated that the BVL would not have the competence to evaluate whether the canola represented a GMO and that this regulatory decision would fall into the sole competences of the European Commission. Moreover, the objection criticized that a nonapplication of coexistence rules to Cibus’ canola would carry high risks of crossover with conventional canola as this crop is one of the most frequently planted crops in Germany (Brockmann, 2015).

In June 2015, the BVL (2015b) rejected the legal objection and confirmed its initial notification, though this did not induce the anti-coalition to resign. On the contrary, the latter issued a legal complaint against the BVL’s rejection in July 2015, obligating the BVL to inform the European Commission by the end of that same month that the court proceedings effectuated a suspension of its regulatory decision. As a result, this prohibited Cibus from carrying out further field trials in Germany, at least not until a final court decision was reached. In the meantime, in June 2015, as another result of these proceedings in Germany, the European Commission (2015) warned the member states against the unauthorized approval of field trials with Cibus’ canola.

The authority stated that it had already conducted a legal analysis of NPBTs and their resulting products against the backdrop of Directive 2001/18/EC. They therefore asked the member states to adopt a “protective approach,” which meant that they should not approve field trials with the canola—as well as stop existing experiments—until the legal status of NPBTs could be clarified at the EU level (European Commission, 2015). It took three more years until the CJEU ruled that the NPBTs represent genetic engineering techniques and that products of these new tools fall within the scope of Directive 2001/18/EC (CJEU, 2018). Accordingly, the BVL withdrew its regulatory opinion on Cibus’ canola in August 2018, and, since then, the scientific authority has considered the modified crop as being a GMO (BVL, 2018).

Taken together, the in-depth study substantiates our assumption that institutional closedness represented an important factor for Cibus when calculating its venue choices, since the BVL and Cibus’ consultant, Perseus, addressed the topics of limited participation and transparency in their communication. Moreover, the venue-internal factor of technical information provided by a venue helps explain Cibus’ choice for Germany. Whether personal contacts influenced the choice for Germany could not be clarified suffiently. However, we could show that venue-external factors can be significant when determining whether lobbyists will achieve their policy goals because a German anti-GMO coalition managed to interfere with the processes of the BVL. Finally, we could show that Cibus accessed the German CA hoping that this would remain hidden; however, the anti-GMO coalition became active and prevented Cibus from obtaining a blank check for NPBT deregulation.

Concluding Remarks

This study investigated the inside lobbying activities of Cibus, a U.S. biotech firm that advocated the deregulation of NPBTs within the EU and hoped thereby to market its newly modified seeds to EU farmers. Based on the concept of venue shopping, the study focused on two main explanations for why this firm chose national CAs in certain member states to pursue NPBT deregulation. Using different sources and methods, the study found general support for both arguments, namely that advocates of unpopular policy objectives favor institutionally closed venues and that they strategically assess the favorability of certain contextual factors before choosing venues.

The results of this study support the argument that advocates of unpopular policy objectives favor institutionally closed venues as these reduce the risk of policy conflicts entering the public sphere. In principle, the EU multilevel system provided Cibus with multiple channels and targets for lobbying NPBT deregulation. However, the company chose the CAs as it could be certain that social debates and policy conflicts would be unlikely to emerge from accessing these bureaucratic and science-based authorities. The case study on Germany substantiates this finding as limited participation and transparency have been important issues in the communication between the German CA (BVL) and Cibus’ consultancy Perseus. However, it also turned out that Cibus chose the CAs both because of their specific competences, which allowed them to classify NPBT-modified crops in regulatory terms, and because of their influence on EU decision making.

The second major argument explaining Cibus’ venue choices was based on the assumption that venue decision makers ultimately represent the key actors who determine whether lobbying activities in these decision-making arenas will be successful. We argued that when advocates lack information regarding the decisions which venue decision makers will likely make, they will strategically consider venue contexts, for these influence the judgments of venue decision makers when dealing with issues that are cutting edge in terms of scientific uncertainty and decision ambiguity. Five indicators were used for assessing how favorable national contexts were toward NPBT deregulation, and two factors were ascertained as explanations for Cibus’ choices of Finland, Germany, Ireland, Sweden, Spain, and the United Kingdom. The first one relates to the high-level political support for agribiotech, as measured by the voting behavior of national governments on the authorization of new GM products in the Council of the European Union. The second factor refers to the economic relevance of national biotech industries, as provided by Cooper (2009). While public opinion on GMOs turned out to have minimal influence, virtually no associations could be observed for prior agricultural application of biotechnology nor for the weakness of domestic anti-GMO lobby groups.

Finally, the case study of Germany revealed that one venue-internal factor also influenced Cibus’ choice for this country, a member state that can be considered as being “conflicted” on agribiotech. This factor relates to specific technical information provided by the venue. More precisely, Cibus could be sure that lobbying the German CA would be successful as it had access to an opinion promoting the deregulation of NPBTs, which was published by the German expert panel (ZKBS) in 2012. Apparently, Cibus knew that this opinion would function as the basis of the BVL’s decision.

Overall, the study showed that lobbyists may carefully consider venue-internal and -external factors to calculate their chances of success before opting for certain venues. Nevertheless, this study examined a very specific empirical case, which is why the generalizability of the results obtained is limited. In order to produce more generalizable insights, and to examine the importance of other influential factors, further qualitative research is needed. Future inquiries could, for instance, analyze how influential resource endowments are for lobbyists’ venue choices. This determinant is widely considered influential, but did not play a role in the case at hand.

The central take-home message for companies and business associations is that looking out for suitable venues is worthwhile, especially if they are seeking to promote unpopular topics. Institutionally closed venues are particularly suitable for advancing unpopular topics, but the suitability of each needs to be carefully assessed in order to minimalize the risk of producing negative effects. In addition, considering venue-internal information, such as the decisions which decision makers will (most probably) reach on certain issues, and venue-external information, such as societal and political support for policy topics, is particularly important. Policy makers can take away from this piece that scientifically and technically based decisions can spark societal conflicts if they become known to the general public. If this is the case, political actors need to take the appropriate decisions through democratic procedures. Finally, if civil society is interested in uncovering inside lobbying activities, it should support respective interest groups and NGOs as these have the means to investigate such lobbying tactics, initiate public discourses, and even take legal action.

Acknowledgments

Simon Schaub deserves credit for several valuable comments and Laurence Crumbie for language-editing the manuscript. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

[Correction added on October 21, 2020, after online publication: Projekt Deal funding statement has been added.]

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

Biography

Ulrich Hartung is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Political Science at Heidelberg University, Germany. His research interests include comparative policy analysis, risk governance, and in particular the regulation of biotechnology in the EU multilevel system.