Legal status and refugees' perceptions of institutional justice: The role of communication quality

Abstract

What factors influence refugees' perceptions of justice in bureaucratic institutions? As global migration movements draw increasing attention, migrants' experiences as constituents in destination countries merit further research. Drawing evidence from the 2018 survey of refugees participating in the German Socio-Economic Panel, this article examines the role of legal status in shaping perceptions of justice at government offices. Our findings highlight a stark contrast: refugees with unstable legal statuses often perceive bureaucratic proceedings as less just compared to those with firmer legal standings. However, refugees' perceptions of a more positive encounter their encounters with street-level bureaucrats can act as a buffer against the negative effects of legal status on perceptions of justice at government offices. These insights underscore a pressing policy implication: asylum procedures, currently marked by ambiguity and delays, could benefit significantly from enhanced communication quality on the part of street-level bureaucrats.

Evidence for practice

- When constituents perceive public institutions as fair and just, they are more likely to trust and comply with governmental decisions and policies, and it is therefore in the interest of government agencies to guarantee all constituents—including noncitizens—procedural and interactional justice during bureaucratic encounters.

- Refugees with precarious legal status, such as asylum seekers and rejected asylum seekers given temporary permission to remain in the country, are less likely to indicate that procedural justice was fulfilled in their encounters with government institutions.

- Perceptions of interactional justice, or whether street-level bureaucrats communicate sufficient information in a respectful manner, can contribute to some improvement in refugees' perceptions of procedural justice.

- Particular attention should be devoted to training street-level bureaucrats in communication approaches that uphold high standards of interactional justice and resonate with broader values of social justice and equity to ensure that marginalized constituencies in general are equally served.

INTRODUCTION

Fairness is a fundamental principle underlying democratic governance and public administration. When individuals perceive public institutions as fair, they are more likely to trust and comply with governmental decisions and policies (Grimes, 2006; Jimenez & Iyer, 2016; Marien & Werner, 2019). Conversely, perceptions of unfairness can erode public trust and lead to diminished cooperation and compliance (Cook et al., 2005). The trust citizens place in public institutions is therefore crucial for maintaining social cohesion and effective governance. Much of this trust is dependent upon constituents' perceptions of procedural justice—or following the rules of fairness—in their interactions with bureaucratic institutions (Kumlin & Rothstein, 2005; Lens, 2009; Tyler, 2006).

As the “face of government” (Lipsky, 2010), street-level bureaucrats (SLBs), or the client-serving government employees who work in local government offices, can have a strong impact on clients' perceptions of fairness in government agencies (Cook et al., 2005; Raaphorst & Van de Walle, 2018). In particular, their actions shape constituents' experiences of interactional justice, which concerns the quality of interpersonal treatment constituents receive (Bies, 1986). When bureaucrats communicate transparently, respectfully, and equitably, it enhances perceptions of fairness and fosters trust in public institutions (Raaphorst & Van de Walle, 2018). Conversely, poor communication can lead to feelings of frustration, powerlessness, and perceptions of unfair treatment, eroding trust and challenging the legitimacy of bureaucratic systems.

While perceptions of street-level procedural and interactional justice can contribute significantly to constituents' confidence in authorities (Kang, 2022; Tyler & Jackson, 2014), evidence indicates that justice is not always distributed equitably. Vulnerable groups, including immigrants and refugees, are susceptible to both individual and systemic forms of discrimination and unequal treatment on the street level (Halling & Petersen, 2024; Reeskens & van der Meer, 2019; Vetters, 2022). Such experiences of unfair treatment may lead to decreased trust in government among these constituent groups (Kang, 2022). This challenge frames our study: democratic governance requires the inclusion of immigrants in policy and practice (Carens, 2013), even down to the street level. As Larrison and Raadschelders (2020) observe, a public administration approach may contribute to our understanding of this policy implementation challenge through studying justice and social equity in street-level encounters.

Using Germany as a case setting, this article examines perceptions of fairness and procedural justice in bureaucratic encounters among a particular group of constituents: refugees. Bureaucracy is particularly present in refugees' first months and years in Germany (Pearlman, 2017), confronting, as Jackson (2008, p. 70) describes, “the bureaucratisation of everyday life in Europe.” Even among vulnerable groups, immigrants (Brussig & Knuth, 2013; Hemker & Rink, 2017; Ratzmann, 2022) and refugees (Ferreri, 2022; Pearlman, 2017) face even greater information asymmetries than many non-immigrant clients due to language barriers, lack of documentation, and lack of institutional knowledge. Because of these vulnerabilities, they are at significant risk of unfair treatment in their interactions with SLBs (Bhatia, 2020; Borrelli, 2021b; Menke & Rumpel, 2022).

Asylum seekers are particularly vulnerable due to their precarious legal status. While they wait for their applications to be reviewed and decided upon, asylum seekers endure a period of uncertainty and precarity (Brekke, 2004; Tuckett, 2015). Their application might then be approved, rejected, or approved but with highly restrictive residence conditions, shaping the legal context within which they will live their daily lives in Germany (Sainsbury, 2012). Yet few studies have analyzed how legal status can affect refugees' perceptions of bureaucratic encounters and their trust in institutions (Sohlberg et al., 2022). As the number of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe continues to grow each year (Donato & Ferris, 2020), the refugee population is an ever more significant constituency served by policymakers and government administrators, and research on the administration of policies for migrants should be given further attention (Larrison & Raadschelders, 2020; Raadschelders et al., 2019). Studies of refugees' perceptions of bureaucratic encounters therefore have important implications for fair treatment and equal access to public services, social trust and confidence in institutions, and advancing equity and social justice (Kumlin & Rothstein, 2010; Park, 2022; Rothstein & Stolle, 2001).

To study the link between refugees' legal status, their perceptions of the fairness of street-level bureaucrats, and the role of procedural justice, we utilize survey data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), in particular a battery of questions that refugees were asked about procedural and interactional justice at bureaucratic institutions. We find that precarious legal status negatively affects refugees' perceptions of procedural justice, but this effect can be partially mediated when interactional justice is upheld in encounters with street-level bureaucrats. We conclude that legal precarity is a significant factor shaping individuals' relationships with bureaucratic institutions and briefly discuss some takeaways for policymakers.

CASE SETTING: ASYLUM SEEKERS IN GERMANY

Germany serves as a particularly interesting case study to look at perceptions of bureaucratic fairness among disadvantaged groups. While it was also a large immigrant-receiving country before the Syrian “refugee crisis,” hosting around 800,000 arrivals per year in the early 2000s and over 1 million per year by 2012, Germany then took the international stage as the fourth-largest destination for refugees (UNHCR, 2023) with Angela Merkel's famous “Wir schaffen das” (“we'll manage it”) speech in August 2015. Germany currently hosts 59 percent of the over 1 million Syrians who migrated to Europe (UNHCR, 2021), and approximately four out of five asylum applications are approved each year (Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik & Stiller, 2023). Its long-term status as an immigration country and eventual place on the European stage as a refugee-receiving country merits investigation into how this new and significant constituency experiences and perceives bureaucratic processes.

Asylum seekers begin their settlement in Germany with bureaucratic encounters. To establish legal residence, asylum seekers report to one of the state-administered offices of the Federal Agency for Migration & Refugees (Bundesministerium für Migration und Flüchtlinge, or BAMF) either at the border or soon after arrival. Upon registration with the BAMF, applicants may continue to reside in Germany with entitlement to state support through asylum seekers' benefits, but significantly limited labor market and mobility rights (Brücker et al., 2019). Asylum seekers' benefits are accessed through an office for refugee affairs, a welfare office, or a reception agency depending on the locality (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz (AsylbLG), 1993). In the meantime, the asylum application review may potentially take a year or more.

The asylum interview takes place at the BAMF and is conducted by an individual decision-maker with an interpreter present. Protection seekers generally receive one of four possible decisions on their asylum application: (1) entitlement to asylum, (2) refugee protection, (3) subsidiary protection, or (4) a ban on deportation or tolerated stay (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2023). These four forms of protection are based on various international or national laws, such as the Geneva Convention, and come with different legal rights. The asylum application is rejected and the applicant is obligated to leave the country when none of these forms of protection can be considered, generally because they are from a so-called “safe country of origin” and have not otherwise provided proof of persecution in the home country. Those who are granted an entitlement to asylum, refugee protection, or subsidiary protection receive a residence permit that entitles them to unrestricted labor market access and social benefits within the German welfare system.

Applicants who are issued the fourth possible decision—the tolerated stay—can legally reside in Germany for a limited period due to deportation impediments that were not considered in the asylum process. Tolerated stay holders are barred from the labor market except with permission from the BAMF, which must be requested for specific job offers, and continued to receive the same social welfare support as asylum seekers. Furthermore, tolerated stay residence permits must be frequently renewed—as deportation is only meant to be temporarily suspended—leading many temporary stay holders to hold a “chain” of short-term residence permits for an indefinite period that can often last years (Schütze, 2023). According to the federal government, around 242,000 individuals are currently living in the country under a tolerated stay, with “missing travel documents” listed as the second most common reason besides “other,” which is the largest official grounds for granting a tolerated stay (Deutscher Bundestag, 2022). Similar to asylum seekers, tolerated stay holders reside in Germany in a position of de facto legal recognition yet continued legal uncertainty or limbo (Dimova, 2006; Schütze, 2023). However, tolerated stay holders have already applied for asylum—and perhaps even appealed the decision—and received a rejection.

As demonstrated in this review of the asylum process in Germany, refugees encounter bureaucracy many times throughout their initial months and years in Germany. After their initial arrival in Germany, they visit the BAMF, immigration office, or reception agencies often several times in the process of securing legal residency. During this time, they may visit the welfare office to receive social support, which they then receive at the general unemployment office after their asylum case is approved. Their experiences at these offices are the subject of our study.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

Constituent perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice

Decades of studies have been devoted to constituents' experiences with and attitudes towards bureaucratic institutions. In general, scholars have demonstrated that individuals are more likely to trust and comply with governmental decisions and policies when they perceive public institutions to be fair (Grimes, 2006; Jimenez & Iyer, 2016; Marien & Werner, 2019). In the context of government services, studies of bureaucratic fairness often focus on perceptions of justice, which a long-standing body of research has divided into three dimensions. Procedural justice, distributional justice, and interactional justice have all been found to contribute to constituents' perceptions of both the outcomes and processes of government services as fair (Blader & Tyler, 2003; Colquitt, 2001; Tyler, 2006). This study focuses on procedural and interactional justice, both of which are related to the processes of providing government services.

Procedural justice focuses on the procedures used in organizations to distribute outcomes. From a sociological perspective, procedural justice entails decision-making that follows the rules of fairness, in particular “neutrality, transparency, factuality and lending a voice to those whose fates are decided upon” (Borrelli & Wyss, 2022; Thibaut & Walker, 1975; Tyler, 2010). Rather than outcomes, procedural justice concerns bureaucratic processes and perceptions of these processes as fair, consistent, and unbiased (Cropanzano et al., 2007; Tyler, 2006). Procedural justice can therefore significantly contribute to public confirmation of political institutions as legitimate and worthy of trust (Grimes, 2006; Lens, 2009; Rothstein & Stolle, 2001).

Constituents judge the fairness of bureaucratic institutions not only by how decisions are made but also by how street-level bureaucrats communicate those decisions to them (Bies & Shapiro, 1987; Kihl, 2023; Lipsky, 2010). As Bies (2015) observes, people are not just concerned about outcomes and procedures, but also that they are treated with respect and dignity. In the organizational justice literature, this is also referred to as interactional justice (Colquitt, 2001). Interactional justice is composed of two dimensions: informational and interpersonal justice (Cropanzano et al., 2007; Döring, 2022). Informational justice describes whether constituents were provided with the information and explanations required to understand actions and decisions. It is also important that government employees supply this information without lengthy delays and red tape (Moynihan & Herd, 2010). When bureaucrats provide constituents with the information they need to access government services in a clear and timely manner, constituents are more likely to evaluate their experiences with bureaucracy positively (Li & Shang, 2020). Interpersonal justice refers to whether communication took place in a polite and respectful manner. In addition, agencies need to consider the individual needs of the constituent and convey information in a way that they can understand (Luoma-aho & Canel, 2020). Several studies have demonstrated that when bureaucrats communicate with constituents in a manner that upholds high standards of interpersonal justice, they are more likely to evaluate even negative decisions as fair (Esaiasson, 2010; Holt et al., 2021; Lind et al., 2000).

Refugees' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice

While a growing body of research has examined constituent perceptions of procedural and interactional justice, only a few studies have explored these perceptions more specifically among refugees. So far, limited research in the public administration field has been conducted on migrants' encounters with street-level bureaucrats, mostly focused on the role of street-level bureaucratic discretion in implementing policies or making decisions on residence permits (Alpes & Spire, 2014; Belabas & Gerrits, 2017; Larrison & Raadschelders, 2020). In addition, several studies describe the myriad bureaucratic challenges that recent refugees face as they settle in Germany and their views and impressions of these challenges (Etzel, 2022; Pearlman, 2017, 2020). In general, refugees tend to express both appreciation and frustration in the face of significant government support as well as significant bureaucratic obstacles (Bucken-Knapp et al., 2020; Schierenbeck et al., 2023). Overall, these studies provide insights into refugees' experiences of local service provision, a main site of refugee policy administration (Raadschelders et al., 2019). Except for Sohlberg et al. (2022)—who find that among a survey of refugees in Sweden, longer asylum waiting periods are associated with lower levels of trust in government—recent research could benefit from further representative studies to shed light on generalized patterns of refugees' views of their interactions with bureaucratic institutions.

Most recent scholarship on refugees' bureaucratic encounters has demonstrated the role of street-level bureaucrats' discretion in shaping experiences of interactional justice. Anti-immigrant political views, xenophobic attitudes (Fekjær et al., 2023; Ratzmann, 2021), or distrust (Borrelli & Wyss, 2022) may influence how bureaucrats treat immigrant constituents. In addition, social imaginaries of refugee “deservingness”—as demonstrated by media, political, and popular discourses—delineate “deserving” and “undeserving” refugees along lines of culture, religion, ethnicity, and human capital (Holmes & Castañeda, 2016; Holzberg et al., 2018). Refugees who are religiously and culturally closer to the “majority” are often portrayed as less threatening and more welcome, while more highly educated refugees are portrayed as an economic asset to the host society (Bansak et al., 2016; Hager & Veit, 2019; Reeskens & van der Meer, 2019). Naturally, bureaucrats are not isolated from these public discourses, and recent studies have observed bureaucrats using deservingness criteria in service provision to refugees (e.g., Ataç, 2019; Borrelli, 2022; Etzel, 2022). Yet refugees' perceptions of their encounters with bureaucrats have yet to be extensively studied. One exception is the work of Larrison and Edlins (2020), whose research indicated that the tone of encounters between street-level bureaucrats and unaccompanied minors, as well as bureaucrats' willingness to speak the minor's native language, can leave a lasting impression.

The role of legal status and hypotheses of the study

One major characteristic of refugees that sets them apart from other constituents is their legal status. Despite the omnipresent role of legal status in shaping refugees' everyday lives (e.g., Kosyakova & Brenzel, 2020; Sigona, 2012), its effect on their experiences with bureaucracy has received little scholarly attention overall. Several forms of legal protection for asylum seekers in Germany entail different implications for reception and integration (Chemin & Nagel, 2020). Recent literature has analyzed variation in the policy inclusion of immigrants and refugees with different legal statuses in access to government services (e.g., Ambrosini, 2021; Ataç, 2019; El-Kayed & Hamann, 2018; Könönen, 2018). On the street level, others have found evidence that SLBs working in immigration and asylum offices may treat refugees with precarious legal status differently compared to those with good “prospects to remain” (e.g., Borrelli, 2018, 2021b; Kosyakova & Brücker, 2020; Schultz, 2021). As noncitizens with limited rights, refugees face a heightened power differential in interactions with street-level bureaucrats, who may make decisions that deeply affect their livelihoods (Edlins & Larrison, 2020). For example, Ataç (2019) observes the role of street-level bureaucrats in gatekeeping non-removed rejected asylum seekers' access to housing (see also Chauvin & Garcés-Mascareñas, 2012). However, limited research has explored how legal status impacts refugees' interactions with other bureaucratic agencies. Furthermore, these studies do not examine the impact of legal status on bureaucratic encounters from the perspectives of refugees themselves.

We suggest several reasons why refugees with an insecure legal status may perceive bureaucratic encounters more negatively. For one matter, refugees applying for asylum may experience bureaucratic processes that are ambiguous, uncertain, and drawn-out and can therefore be frustrating and anxiety-inducing (Brekke, 2004; Tuckett, 2015). In addition, long waiting periods for asylum can contribute to decreased perceptions of fairness and procedural justice. Asylum seekers can potentially wait for over a year before their case is processed (Connor, 2017). A long waiting period for the asylum decision has been linked to stress, discouragement, and even mental health challenges (Hainmueller et al., 2016; Hvidtfeldt et al., 2020). Most recently, Sohlberg et al. (2022) link longer waiting time for the asylum decision with decreased trust in institutions. The tolerated stay status, with its inherent legal, economic, and social exclusion, has also been found to negatively affect feelings of belonging, mental health, and one's sense of stability (Jonitz & Leerkes, 2022; Tize, 2021). We suggest that this ongoing marginalization, limited rights, and limited government support may contribute to decreased confidence in German bureaucratic institutions. In light of this insecurity faced by asylum seekers and tolerated stay holders due to their legal status, we expect that asylum applicants as well as those with a tolerated stay will perceive lower levels of procedural justice in bureaucratic encounters (H1).

We also expect the effects of legal status to carry over into street-level interactions. Some recent studies have investigated how SLBs in migration agencies treat refugees with precarious legal status (Borrelli, 2018, 2021a; Schultz, 2021). However, these studies generally lack a comparison with refugees with more secure residence permits. Bonoli & Otmani (2023) find evidence that precarious legal status plays a role in Swiss case workers' decision-making regarding refugees' employment prospects and career choices, as they decide it is not worth investing in upskilling for refugees who may soon leave the country. Not only is it possible that SLBs will treat precarious refugees more poorly than those with a more secure legal status but it is also likely that precarious refugees will view their interactions with SLBs more negatively, as the marginalization and insecurity they face due to their legal status may negatively affect their perceptions of bureaucracy and bureaucratic actors. In addition to decreased satisfaction with their overall experience at bureaucratic agencies, we therefore also expect that asylum applicants as well as those with a tolerated stay will evaluate their experiences of interactional justice with SLBs more negatively (H2).

We also consider whether the relationship between procedural and interactional justice may moderate the impact of legal status. As Cropanzano et al. (2007, p. 39) observe, “The ill effects of injustice can be at least partially mitigated if at least one component of justice is maintained.” As the government employees responsible for delivering government services “on the ground,” SLBs, if they treat constituents with a high level of interactional justice, may therefore affect constituents' overall perceptions of procedural justice. Most recently, for example, Gornik's (2022) study of unaccompanied minor refugees indicated that overall perceptions of experiences with asylum bureaucracy were most strongly influenced by perceptions of interactional justice. We consequently propose hypothesis (H3), that perception of greater interactional justice with SLBs mediates some of the negative effects of precarious legal status on perceptions of procedural justice. We test the three above hypotheses in the following analyses.

ANALYTICAL APPROACH

Data and sample

Launched in 1984, the German SOEP is a unique and extensive dataset that encompasses a broad range of socio-economic aspects of German society. The SOEP uses a multi-stage stratified random sampling design to ensure its representativeness of the German population (SOEP, Data from 1984 to 2019, EU Edition, 2021). Additionally, the panel follows a refreshment strategy to include newly formed households, foreign-born individuals, and oversamples of specific population subgroups, such as low-income households or individuals aged 67 and above. Data collection for the SOEP occurs annually through face-to-face interviews conducted by trained interviewers using computer-assisted personal interviewing techniques. The interviews typically cover a wide array of topics, including socio-demographic characteristics, employment history, income and wealth, education, health, and subjective well-being.

One particular subset of the SOEP is the IAB-BAMF-SOEP survey of refugees (Samples M3-M5). Launched in 2016, the sample includes adult refugees who arrived in Germany since 2013 seeking asylum (IAB-SOEP Migration Samples [M3–M5], Data of the Years 2013–2019, 2021). In addition to the questions asked of other SOEP respondents, respondents in the Refugee Sample receive questions concerning language use, living situations, family situations, social participation, contact with both Germans and people of their own ethnic backgrounds, and finally—serving the interest of this study—questions concerning experiences with legal and bureaucratic institutions.

In 2018, only the SOEP respondents in the Refugee Sample were asked a battery of questions expressly concerning procedural and interactional justice during visits to government agencies. This section included questions about their awareness and use of various support services for navigating the asylum process and bureaucratic agencies; their satisfaction with experiences at various government offices; and finally, seven questions asking respondents to evaluate their last interaction with a government clerk. As our dependent variable of interest is comprised of these questions, we restrict our sample to adults in SOEP Samples M3-M5, the Refugee Sample, who answereed these questions in 2018. The total number of person-observations is 3911.

Descriptive statistics: Main dependent and independent variables

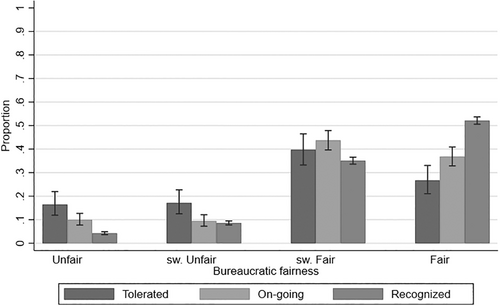

Our dependent variable is respondents' perception of procedural justice. Specifically, respondents were asked the question, “If you think about your experiences with offices (BAMF, BA, others) so far, how fair do you feel treated?” Respondents could choose their answer on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 meaning “fair,” and 4 meaning “unfair.” 1 Our main independent variable is the legal status of respondents. This categorical variable distinguishes between the legal status of persons whose asylum application was rejected and are residing in Germany on a tolerated stay; ongoing applicants whose asylum case is not yet decided; and those who received recognized entitlement to asylum. After excluding observations with missing values and unclear legal status, our analytical sample includes 3323 person-observations. Approximately 84 percent of the sample have received a recognized entitlement to asylum, while a further 12 percent are in the process of applying, and the remaining 4.4 percent have a tolerated status. The average perception of bureaucratic fairness in the sample is 3.3 on a 4-point scale. Persons with a recognized entitlement to asylum tend to have the highest perception of fairness compared to other legal status groups in the sample. The mean fairness perception score among recognized refugees is 3.35, higher than that in the group of ongoing applicants (3.07) and rejected applicants (2.77).

Figure 1 presents categories of procedural justice perceptions by legal status and associated 95 percent confidence intervals. Differences between refugee groups are particularly visible when comparing perceptions of bureaucratic offices as “fair” or “unfair,” the two ends of the scale of possible answers. Relative to other groups, persons with entitlement to asylum are significantly more likely to perceive bureaucratic treatment as fair and less likely to perceive treatment as unfair. Differences between groups in the middle categories (i.e., somewhat unfair and somewhat fair) are less pronounced and often not statistically significant.

We construct our mediator variable—which concerns respondents' perceptions of interactional justice in their experiences with SLBs—using answers where respondents were asked to rate seven statements about their last encounter with a government clerk. Specifically, respondents were asked to answer the following question, “Please think about your last talk with your person in charge (‘Sachbearbeiter/in’). How far do the following items apply? Please answer the following question in relation to the office you last had contact with.” Respondents were asked to rate seven statements on a scale from 1 to 4, with 1 meaning “applies completely,” and 4 meaning “does not apply at all.” These seven statements all concern aspects of interactional justice in government clerks' communication with respondents, more specifically informational justice (whether the clerk provided sufficient information and explanations and communicated in a timely manner) and interpersonal justice (whether the clerk treated the respondent with respect and adapted explanations to their personal needs). Table 1 lists these seven statements with mean answers by legal status group.

| Tolerated | Ongoing | Recognized | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interactional justice (0–10) | 7.05*** | 7.63*** | 8.19 |

| My person in charge thoroughly and intelligibly explained the rules and regulations | 3.08*** | 3.27*** | 3.42 |

| My person in charge gave me exact reasons for the making of their decision | 3.02*** | 3.22*** | 3.37 |

| My person in charge provided information openly and honestly | 3.16*** | 3.29*** | 3.49 |

| My person in charge treated me politely and respectfully | 3.29*** | 3.56** | 3.66 |

| My person in charge informed me in time about important facts and details | 3.15*** | 3.28*** | 3.45 |

| My person in charge adapted his advices and explanations to my personal needs | 2.96*** | 3.07*** | 3.30 |

| My person in charge uttered inappropriate remarks and comments | 3.32*** | 3.53* | 3.63 |

| Number of observations | 146 | 391 | 2786 |

- Note: Number of observations 3323. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 refer to two sample t-test on the equality of means with recognized asylum group. Interactional justice score (0–10) is predicted by the regression method based the results of factor analysis (Table 1A).

- Source: Authors' calculations based on Socio-Economic Panel-Core, v36 (EU Edition), doi: 10.5684/soep.core.v36eu.

To summarize respondents' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice in a single score, we carry out an exploratory principal component factor analysis. We retain a single factor with an eigenvalue of 4.02 that accounts for 67 percent of variance in the data. The eigenvalue for the second factor is 0.6. Table 1A provides resulting factor loadings. With a value of Cronbach's alpha of 0.90, our scale exhibits high reliability. We exclude the item, “My person in charge uttered inappropriate remarks and comments,” because changes in Cronbach's alpha indicate that the inclusion of this item decreases overall scale reliability. We normalize the values of the scale to range from 0 (very poor communication) to 10 (excellent communication) and refer to the resulting factor as a scale of interactional justice. The average value of the interactional justice score is 8.25, suggesting an overall high level of perceived interactional justice. In line with the results reported earlier, we find significant differences in perceptions of interactional justice by legal status. Persons with recognized entitlement to asylum report the highest interactional justice scores, followed by persons that are in the process of application. Finally, persons with tolerated stay status report the poorest interactional justice. Persons with recognized entitlement to asylum have the highest scores on each dimension of interactional justice, followed by persons who are in the process of applying for asylum. Persons under a tolerated stay generally rate interactional justice the lowest.

Empirical strategy

In the final step, we extend the first model to include respondents' perceptions of interactional justice and examine whether this factor can mediate some of the effects of legal status on perception of procedural justice (H3). To achieve this, we use the mediation model proposed by Karlson, Holm, and Breen (KHB) (Breen et al., 2013; Karlson et al., 2012). The KHB method allows us to compare estimated coefficients between two nested nonlinear probabilities models, accounting for the lack of separate identification of coefficients and error variances in these models. The method enhances the reduced model by incorporating residuals obtained from regressing the mediator variable (procedural justice) on the key explanatory variable (legal status). This approach enables us to disentangle differences attributed to mediation from differences arising from rescaling with distinct error variances.

RESULTS: DETERMINANTS OF PROCEDURAL AND INTERACTIONAL JUSTICE PERCEPTIONS

Procedural justice

We proceed by examining the effect of legal status and other control variables on procedural justice perceptions. Table 2A summarizes covariates used in the estimation of Equation (1). We exclude a small number of observations with missing values in the explanatory variables. As a result, the number of observations in the estimation sample is slightly lower (3233 observations) than that reported in Table 1.

Given that our dependent variable has a natural order, the appropriate modeling choice would be to estimate an ordered response model. However, the proportional odds assumption, which underlies this model, is violated in our case, as indicated by the Brant test (χ2(62, N = 3233) = 126.87, p > .000) (Brant, 1990). As a result, we refrain from using the ordered response model and instead opt for estimating a binary choice model with an indicator variable to represent respondents who perceive treatment by bureaucrats as fair, i.e., high procedural justice. We discuss the results of four specifications in which we include explanatory variables in a stepwise approach. In the modeling process, we first control for the effect of legal status, then add variables that describe respondents' demographic profiles, migration-related variables, and finally variables that capture employment status and income. In all specifications, we control for the last government office with which the respondent last had contact.

Table 2 summarizes average marginal effects based on the estimation of the logit model. Consistent with the descriptive results in Table 1, the estimates show a sizable gap in the probability of perceiving the last-visited government office as fair between groups of refugees defined by legal status. Refugees in more precarious situations, i.e., those under tolerated stay status or those waiting for a decision, have a lower probability of perceiving treatment by bureaucrats as fair relative to refugees with recognized entitlement to asylum. We observe that the gap in procedural justice perceptions remains rather stable even after including an additional extensive set of control variables. This suggests that the relationship between legal status and procedural justice perceptions is robust and likely not purely driven by observable variables.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerated stay | −0.191*** | −0.190*** | −0.188*** | −0.191*** |

| (0.046) | (0.046) | (0.048) | (0.047) | |

| Ongoing application | −0.117*** | −0.119*** | −0.128*** | −0.122*** |

| (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.029) | (0.029) | |

| Recognized asylum (ref.) | ||||

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Employment | No | No | No | Yes |

| Pseudo R2 | .0195 | .0361 | .0413 | .0491 |

| Number of observations | 3233 | 3233 | 3233 | 3233 |

- Note: This table presents marginal effects estimated based on a logit estimation of Equation (1) with the binary dependent variable perceiving bureaucrats as fair. Each column represents a different specification where control variables are included stepwise. Pseudo R2 are from estimation of logit regressions. Logit regressions coefficients and full specifications are presented in Table 3A. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < 0.01.

- Source: Authors' calculations based on Socio-Economic Panel-Core, v36 (EU Edition), doi: 10.5684/soep.core.v36eu.

Based on the specification in column 4, having a legal status other than recognized asylum decreases, on average, the probability of high procedural justice perceptions by 19.1 percentage points for refugees with a tolerated stay status and by 12.2 percentage points for refugees waiting for a decision, holding all other variables constant. This corresponds to a relative effect of approximately 39 percent for refugees with a tolerated stay and 25 percent for refugees waiting for a decision, based on the sample mean on the procedural justice scale (49 percent).

As the results from the Brant test already indicated, the effect of legal status is likely to differ between different levels of procedural justice perceptions. To address this, we analyze in Table 4A how the effect might differ if we specify our dependent variable, procedural justice, to be equal to one if respondents perceive treatment by government officials as either somewhat fair or fair, the two higher values of the four-point scale used in the dependent variable. In line with the main result reported in Table 4A, the effect remains significantly negative but somewhat smaller in absolute value for the group of refugees with the legal status of tolerated stay. For the group of refugees waiting for a decision, the effect turns to be closer to zero and statistically insignificant. In line with the evidence reported in Figure 1, we confirm that legal status is associated with large differences at the end values of the procedural justice scale.

Interactional justice

We next examine the link between legal status and respondents' experience of interactional justice in encounters with SLBs. Table 3 presents estimates resulting from the estimation of the linear regression model. Based on the results in column 4, precarious legal statuses are associated with lower interactional justice scores. Relative to refugees with recognized entitlement to asylum, refugees under the tolerated stay regime report experiencing, on average, 0.80 points lower quality communication, and refugees waiting for a decision report 0.437 points lower quality communication.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tolerated stay | −0.807*** | −0.814*** | −0.791*** | −0.800*** |

| (0.241) | (0.240) | (0.246) | (0.246) | |

| Ongoing application | −0.415*** | −0.444*** | −0.433*** | −0.437*** |

| (0.134) | (0.133) | (0.138) | (0.140) | |

| Recognized asylum (ref.) | ||||

| Demographics | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Migration | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Employment | No | No | No | Yes |

| R2 | .0213 | .0341 | .0360 | .0437 |

| N | 3233 | 3233 | 3233 | 3233 |

- Note: This table presents coefficients of linear regression with the dependent variable interactional justice score. Each column represents a different specification where control variables are included stepwise. Full specifications are presented in Table 5A. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *p < .10, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

- Source: Authors' calculations based on Socio-Economic Panel-Core, v36 (EU Edition), doi: 10.5684/soep.core.v36eu.

Robustness checks

Before testing our last hypothesis, we examine the robustness of our findings against potential omitted variable bias. While detailed results are presented in Appendix 2, we briefly summarize them here. Initially, we evaluated the potential influence of unmeasured personality traits on perceptions of justice. While the 2018 SOEP dataset did not provide variables indicating specific personality traits, it did capture respondents' general perceptions of fairness. About 58.9 percent of respondents in our sample believed that most people act fairly. By incorporating this variable into our models, our primary results regarding legal status and perceptions of justice were reaffirmed. Results of this robustness check are available in the Table 6A.

Subsequently, we applied Oster's (2019) bounding method to address potential outcomes from unobserved selection bias. This robustness check allowed us to determine the impact of unobserved selection on the coefficient of legal status. Under the assumptions of Oster's method, we found our main results to be robust against potential omitted variable bias. Thus, our primary findings regarding legal status influencing perceptions of justice remain well-supported. The results of this robustness check are available in the Table 7A.

Mediation analysis

While procedural and interactional justice can be evaluated separately, there is also some indication in the literature that these components of organizational justice can interact, and that high levels of one dimension of justice can mitigate the negative effects of low levels of another dimension (Cropanzano et al., 2007; Skarlicki & Folger, 1997). To what extent, then, can interactional justice mediate the effect of refugees' legal status on procedural justice perceptions? To gain insight into this issue, we include the interactional justice scale as an additional regressor in the estimation of Equation (1). Table 8A reports average marginal effects. Controlling for the interactional justice score substantially decreases BIC statistics, indicating an improvement in model fit. A one-unit improvement in interactional justice score is associated with an approximately 10 percentage point increase in the probability of higher procedural justice perceptions. To test the hypothesis that interactional justice mediates the effect of refugees' legal status, we report the results of the KHB decomposition procedure. Table 4 presents these results, which suggest that around one-third of the effect of legal status on procedural justice is mediated by interactional justice. The effect is larger for refugees under the tolerated stay (38 percent) than for refugees awaiting a decision (33 percent).

| Reduced | Full | Diff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| b/(SE)/[AME] | b/(SE)/[AME] | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Tolerated stay | −1.080*** | −0.666*** | −0.414*** |

| (0.240) | (0.244) | (0.134) | |

| [−0.206] | [−0.129] | ||

| Ongoing application | −0.682*** | −0.456*** | −0.227* |

| (0.138) | (0.138) | (0.133) | |

| [−0.133] | [−0.885] | ||

| Observations | 3233 | 3233 | |

| Procedural fairness | No | Yes | |

| All controls | Yes | Yes |

- Note: This table displays the results of a logit estimation (as well as average marginal effects [AME] in square brackets) with the dependent variable perceiving bureaucrats as fair. Column (1) shows the reduced model which represents the specification as presented in Equation (1) with the only difference being that residuals of the interactional justice are included as right-hand side variables. Column (2) shows the full model in which the procedural fairness is included into the model as control variable. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *p < .1, **p < .05, ***p < .01.

- Source: Authors' calculations based on Socio-Economic Panel-Core, v36 (EU Edition), doi: 10.5684/soep.core.v36eu.

This mediation analysis has demonstrated that considering interactional justice in encounters with SLBs helps to explain a significant portion of the relationship between a refugee's legal status and their perceptions of procedural justice and fairness at bureaucratic offices. At the same time, legal status remains a significant predictor of respondents' perceptions of procedural justice in bureaucratic encounters.

LIMITATIONS

There are some limitations of our study that should be addressed in future research. First, we cannot rule out reverse causality between procedural and interactional justice. When individuals perceive a process as fair and equitable (high procedural justice), they might be more inclined to view subsequent interactions with bureaucrats through a more positive lens (Moorman, 1991). Even if an authority figure is neutral or somewhat less than cordial, the individual might give them the benefit of the doubt because they trust the overall procedure. Consequently, there is a higher likelihood of perceiving interactions as just (high interactional justice) when the underlying procedures are perceived as fair. While our robustness checks indicate low potential of confounding variables influencing both interactional and procedural justice perceptions, longitudinal studies may be better suited to test reverse causality issues.

Second, we did not disentangle the effects of specific aspects of interactional justice: Since one focus of our study was generalizability, we did not further differentiate our independent variable into aspects of transparency, respect, and equality, all components of interactional justice (Bies, 1986). Instead, we used a more general and compact measure—an aggregate index. At the cost of less generalizability, however, further research can also, and should, focus on specific aspects of communication to investigate the effects of interactional justice.

Third, we did not investigate the behavioral effects of social embeddedness (Granovetter, 1985) within different refugee groups. Social embeddedness refers to the degree to which individuals are integrated into and influenced by their social networks and structures. In the context of refugees, such embeddedness can play a significant role in shaping their perceptions, experiences, and behaviors (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993). By not investigating the behavioral effects of social embeddedness, we might have missed nuanced insights into how these social networks and relationships influence perceptions of justice, and subsequently, the behaviors of refugees. Accepted refugees, who have a clearer path to integration and potential long-term residence, might forge stronger or different types of social connections compared to other refugee groups, who might face more uncertainty and transient relationships. These disparities in social ties could, in turn, shape how each group perceives and reacts to procedural and interactional justice.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In a society where constituents expect institutions to resonate with broader values of social justice and equity, perceptions of fairness and justice in public institutions play a crucial role in encouraging compliance with governmental decisions. It is therefore in the interest of government agencies to guarantee all constituents, including immigrants and refugees, procedural and interactional justice during bureaucratic encounters. This article contributes to scholarly discussions of immigrants' relationships with authorities. As groups who are often marginalized in the destination country and who may experience a significant power imbalance in interactions with bureaucratic agencies (Edlins & Larrison, 2020), it is particularly important to study justice and fairness perceptions among immigrants and refugees. So far, research on immigrant attitudes towards bureaucratic authorities has mainly focused on perceptions of the police and is largely concentrated in the United States. These studies generally indicate find that immigrants' perceptions of the police are influenced by group-specific factors such as experiences with police in the country of origin, length of residence in the U.S., experiences with immigration enforcement—and legal status (e.g., Barrick, 2014; Correia, 2010; Menjívar & Bejarano, 2004). Outside of interactions with police, research on immigrants' experiences of justice has often concerned focused on encounters with immigration enforcement (Ryo, 2021), though in the U.S. context, perceptions of police overlap with perceptions of immigration enforcement as such enforcement is often carried out by police (e.g., Morales & Curry, 2021). Similarly, most studies of refugees' experiences of justice in bureaucratic agencies are relatively recent and have examined focused on the asylum process (Gornik, 2022; Johannesson, 2022; Vetters, 2022) or on the experiences of unaccompanied minors (Edlins & Larrison, 2020; Larrison & Edlins, 2020). We extend this field of scholarship to bureaucratic encounters in Germany.

This article has demonstrated the significance of legal precarity in shaping refugees' relationships with government institutions. Individuals waiting for a decision on their asylum application and persons under the tolerated stay perceive their experiences at government offices as less just than those who had already been recognized as refugees, even after controlling for a larger set of explanatory characteristics. After accounting for the interactional justice score in the mediation analysis, the negative effects of the precarious legal statuses on justice perception are reduced but remains of substantial magnitude. Asylum applicants endure what is often a period of uncertainty and precarity as they wait for a decision (Brekke, 2004; Tuckett, 2015). These long waiting periods not only induce frustration and anxiety but may also leave asylum seekers disillusioned and distrustful of the German government. Tolerated stay holders appear to perceive their experiences with government institutions as even more unjust. Their legal status may be described as a state of what Menjívar (2006) calls “liminal legality.” Liminal legality refers to a legal status of “in-between,” one that is both temporary and can be extended indefinitely, that is ambiguous in that it is neither fully documented nor fully undocumented, and that does not clearly lead to a fully documented status. Such “legal non-existence” and exclusion from the rights and benefits of legal residence may significantly damage tolerated stay holders' perceptions of procedural and interactional justice in their experiences with government agencies. It is therefore particularly important for administrators and policymakers to pay attention to upholding high standards of justice in bureaucratic procedures and encounters with this constituency.

In addition, our findings indicate that when migrant constituents have more positive experiences in their interactions with SLBs—when they are treated with respect and dignity—they also perceive their experiences of the process of accessing government services as more just. As Larrison and Edlins (2020, p. 134) observe, “the way in which [street-level bureaucrats] approach a situation can have as much affect as the situation itself.” These findings present some tangible lessons for SLBs and administrators: for migrants in particularly insecure legal situations, even greater consideration should be given to the tone of communication and to providing thorough information, including rules and regulations, the reasons for decisions, and more. Communicating this information in migrants' native language (Larrison & Edlins, 2020) or in simplified destination country language (Becker, 2020), depending on their skills, may help contribute to perceptions of procedural and interactional justice. More broadly, policymakers interested in improving relationships with marginalized constituencies may devote particular attention to the street-level encounter and to interpersonal communication between constituent and bureaucrat. Greater consideration of these matters may foster perceptions of justice and fair treatment among these constituents, contributing to trust in government.

These results not only demonstrate the relationship between interactional and procedural justice but also indicate that interactional justice perceptions can somewhat decrease the negative effects of legal status on procedural justice perceptions. A substantial effect of legal status on procedural justice perceptions remains and cannot be fully mitigated by respectful communication from SLBs. However, when communication is carried out in a respectful manner and the necessary information is thoroughly provided, even those living in a precarious legal situation may feel that they can trust government institutions more, supporting effective governance upheld by democratic principles. This is yet another important takeaway for practitioners: high standards of procedural and interactional justice may help address the insecurity constituents in precarious legal situations may feel in their interactions with government agencies. Broadening beyond refugee constituents, further research may investigate the role of communication and interactional justice in potentially improving relationships between government and other marginalized constituencies.

Endnotes

Biographies

Emily Frank is a postdoctoral researcher at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center and recently completed her doctorate in a joint program of the Hertie School and Humboldt University Berlin. Her research interests include immigrants' reception experiences in destination countries, the effects of immigration policies and processes on immigrants' mental health and well-being, and the adaptability of public administrations to migration.

Anton Nivorozhkin completed his doctorate at Gothenburg University, Sweden. Since 2005, he has served as a senior researcher at the Institute for Employment Research in Nuremberg, Germany. He has collaborated in various capacities with the OECD, the European Commission, and the World Bank. His research spans a wide range of topics in public policy, administration, and statistics.