Just or Unjust? How Ideological Beliefs Shape Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Perceptions of Administrative Burden

Abstract

Existing research finds that increases in administrative burden reduce client access, political efficacy, and equity. However, extant literature has yet to investigate how administrative burden policies are interpreted by street-level bureaucrats (SLB), whose values and beliefs structure uses of discretion and client experiences of programs. In this article, we utilize quantitative and qualitative data to examine SLB policy preferences regarding administrative burden in Oklahoma's Promise—a means-tested college access program. Our findings demonstrate that SLB in our sample interpret administrative burden policies through the lens of political ideology. Conservative SLB express significantly more support for administrative burden policies, arguing that these policies prevent fraud and demonstrate client deservingness. In contrast, predominantly liberal SLB justify opposition to administrative burden by arguing that the requirements undermine social equity. Together, our findings reveal that SLB political ideology shapes interpretations of administrative burden and perceptions of client deservingness in Oklahoma's Promise.

Evidence for Practice

- Street-level bureaucrats (SLB) vary in the degree to which they perceive administrative burden policies that affect students as just or unjust.

- SLB political ideology affects beliefs about and justifications for administrative burden policies.

- Perceptions of deservingness of target populations shape policy preferences on administrative burden.

- Development of standard operating procedures at the state level will help SLB abstain from the influence of values and ideology and achieve uniformity when implementing policies with administrative burden.

Public administration scholars are increasingly concerned with the potential negative effects of administrative burden—or policy designs that create onerous experiences of government for clients—on program access, social equity, and democratic outcomes (Heinrich 2018; Herd et al. 2013; Herd and Moynihan 2018; Jilke, van Dooren, and Rys 2018; Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey 2015; Nisar 2017). While the dominant narrative in public administration scholarship casts policies contributing to administrative burden as sinister, hidden policy making with deleterious impacts on democratic outcomes, it is unclear whether this narrative reflects the perspectives of those on the front lines of government who bear the responsibility and power to shape client–state interactions (Bell and Smith 2019; Brodkin 2012; Keiser 2010; Lipsky 2010; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003). Indeed, despite the calls to investigate how decision makers distinguish between reasonable and unreasonable administrative burden, scholars have yet to thoroughly investigate how bureaucrats on the front lines of government view administrative burden policies. In this article, we examine SLB policy preferences on administrative burden as well as the narratives these bureaucrats use to justify policy support or opposition.

We leverage a statewide survey of SLB in charge of implementing a means-tested college access program—Oklahoma's Promise—that has been subject to numerous consequential policy changes that have made the program among the most burdensome financial aid programs in the nation (Blatt 2015). This program, like Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), has been scrutinized by conservative legislators who want to reduce the cost of the program and reduce the possibility of fraud, waste, and abuse 1 (Brodkin and Majmundar 2010; Keiser 2010; Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey 2015). This scrutiny catalyzed a series of programmatic policy changes including, but not limited to, the addition of annual income documentation, citizenship documentation, and stringent academic requirements (Bell 2019b). Each of these policy changes is implemented through a decentralized network of SLB (school counselors) whose discretionary decisions affect client interactions with the administrative state (Bell and Smith 2019).

- How do SLB justify their beliefs about administrative burden policies?

- How does political ideology shape SLB perceptions of administrative burden?

Leveraging political science and public administration literature on political ideology, SLB, and client deservingness, we construct a series of hypotheses regarding the likely influence of political ideology on beliefs about administrative burden policies as either just or unjust. Utilizing our qualitative data, we also take the analysis a step further by analyzing why SLB either support or oppose administrative burden. Our findings demonstrate that there is substantial variation in the level of support and the justifications for administrative burden policies across SLB. In line with our hypotheses, we find that conservative SLB are more likely to support requirements that increase burdens on clientele—they are more likely to support citizenship documentation requirements, additional income checks, and restrictions on funding for remedial education. Our findings also reveal stark contrasts in the narratives that SLB utilize to justify policy preferences for administrative burden policies, with social constructions of “earned” deservingness playing an important role in shaping policy preferences (Bell 2019a; Jilke and Tummers 2018; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003; Schneider and Ingram 2012). We find that many conservative SLB support administrative burden policies not only because of the potential to reduce fraud, waste, and abuse but also to ensure that clients demonstrate “earned deservingness” by making it through the administrative hurdles in the application process (Jilke and Tummers 2018; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). In contrast, SLB identifying as liberal were more likely to interpret administrative burden policies as unjust threats to social equity that create undue barriers to access for the most marginalized clientele. These findings suggest that the politics of administrative burden extend to the street level where the values and beliefs of SLB shape narratives surrounding policy design and client deservingness.

These findings have two main contributions to existing literature. First, we leverage political science research on ideology and social constructions to theoretically explore and empirically test the hypothesis put forth by Herd and Moynihan (2018) that the ideology of SLB will shape interpretations of administrative burden. In doing so, our work explores whether the Weberian classic approach of bureaucratic neutrality and Wilsonian tradition of professionalism applies to the implementation of administrative burden at the street level or whether politics prevails (Brewer and Walker 2010; Wilson 1887; Zarychta, Grillos, and Andersson 2020). Second, while previous studies on ideology and bureaucratic policy preferences have focused on policies that increase internal organizational red tape, we highlight preferences on policies affecting extraorganizational interactions between clients and the administrative state (Burden et al. 2012; Lavertu, Lewis, and Moynihan 2013; Rainey, Pandey, and Bozeman 1995). This allows us to explore the previously understudied interaction between ideological beliefs and perceptions of client deservingness in determining SLB policy preferences regarding administrative burden (Jilke and Tummers 2018; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003).

In the following discussion, we situate our article in existing administrative burden literature and present our set of theoretical hypotheses regarding political ideology and beliefs about administrative burden at the street level. Thereafter, we present the policy context, data sources, and methodology. Finally, we discuss the findings and implications for public administration theory and practice.

The Politics of Administrative Burden

Public administration scholars have argued that administrative burden is a venue of hidden politics (Herd and Moynihan 2018). Instead of reducing funding or eliminating programs, which has the potential to spark outrage, political actors can impose learning, compliance, or psychological costs on the public and thereby ration limited public resources without the scrutinizing view of the public. 2 In this way, burdens are often the product of intentional political choices, though they can also be caused by informal organizational practices and restricted administrative capacity (Herd and Moynihan 2018; Peeters 2019). By shifting the burden away from the state and onto clients, political actors impose (1) learning costs (the time it takes to learn about program requirements and eligibility), (2) compliance costs (the time and effort it takes to submit all of the required paperwork and application materials), and (3) psychological costs (the loss of autonomy and stigma induced in applying for programs). In turn, the client's experience with government programs becomes onerous, which shapes program access (Daigneault and Macé 2019; Heinrich 2016; Heinrich and Brill 2015; Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey 2015; Reijnders, Schalk, and Steen 2018), political efficacy and civic engagement (Bruch, Ferree, and Soss 2010; Soss 1999), and perceptions of government effectiveness more broadly (Heinrich 2018). When public programs are rife with learning, compliance, and psychological costs, access to public programs, such as TANF and workforce training, significantly decreases (Cherlin et al. 2002; Herd and Moynihan 2018). Moreover, the most pronounced negative effects of administrative burden occur among marginalized groups who have fewer resources to draw from when interacting with administrators (Brodkin and Majmundar 2010; Jilke, van Dooren, and Rys 2018; Nisar 2017. 2018).

The current state of the literature makes it clear that administrative burdens in the form of rules and policies lead to negative effects on program access and social equity. However, this literature has yet to develop an understanding of the interpretations of administrative burden by key personnel, such as SLB. Administrative burden policies are not self-implementing; they function through the strategic uses of discretion by key actors, including SLB (Bell and Smith 2019; Jilke, van Dooren, and Rys 2018; Peeters 2019). While procedural accountability assumes that decisions must be taken in accordance with known and established processes (Romzek and Dubnick 1987), uses of discretion at the front lines of government are often not the product of neutral competence but instead the product of moral decisions rooted in individual values and beliefs (Keiser 2010; Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011; Watkins-Hayes 2009). In fact, absent clear-cut rules and standard operating procedures (SOPs) to preclude discrimination, the discretion provided to street-level bureaucrats fosters the possibility that they act upon their own biases (Lipsky 2010).

Existing work on the policy preferences of SLB has found that factors such as community and individual ideology (Stensöta 2012) and strategic communication are important in predicting policy preferences (Andersen and Jakobsen 2017). For example, at the managerial level, the implementation of the Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART) was perceived as more burdensome by employees in liberal agencies compared to conservative agencies, even after controlling for objective differences in the demands of PART across agencies (Lavertu, Lewis, and Moynihan 2013). These differences in policy preferences and perceptions of policy as burdensome for internal organizational functioning “can help explain the application of discretion—for example, what decisions are made, how clients are dealt with, and which tasks are pursued or neglected” (Burden et al. 2012, 749). Recent experimental studies further demonstrate the importance of SLB values and beliefs for the use of discretion, finding that partisanship and racial bias impact the use of discretion and access to services for clients (Bell and Smith 2019; Einstein and Glick 2017; Jilke, Van Dooren, and Rys 2018; Porter and Rogowski 2018; White, Nathan, and Faller 2015). Therefore, the perceptions and ideologies of SLB are consequential for policy implementation due to the use of discretionary power at the front lines of government and deserve future exploration in the context of administrative burden policy regimes that form information, compliance, and psychological barriers to access for clients (Bell and Smith 2019; Brodkin and Majmundar 2010; Jilke, van Dooren, and Rys 2018; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011; Watkins-Hayes 2011).

Street-Level Bureaucrats, Ideology, and Policy Preferences on Administrative Burden

Building on this existing literature, we examine SLB policy beliefs regarding provisions that increase onerous experiences of policy implementation for clients. Drawing on research in political science, we further conceptualize and empirically test the proposition put forth by Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey (2015) that “the policy preferences of…. SLBs affect their attitudes about the nature of burden in that policy area” (52). 3 This empirical question, which contradicts the notion of neutral competence among SLB, has yet to be directly tested and merits further conceptualization and expansion.

In political science research, it is well established that, among members of the public, policy preferences are heavily swayed by the manipulation of policy images by political elites (Druckman, Peterson, and Slothuus 2013; Poole and Rosenthal 2000; Rodriguez, Laugesen, and Watts 2010). This is because the public has a need for credible information but has inadequate time and energy to devote to developing an informed opinion on every issue. Consequentially, members of the public satisfice by adopting the narratives and predominant policy images put forth by political elites on their side of the ideological spectrum (Druckman 2001; Feldman and Zaller 1992).

However, the notion that SLB would also be subject to the same political influences in the development of policy preferences contradicts the Wilsonian tradition of bureaucratic professionalism and neutral competence (Brewer and Walker 2010; Wilson 1887; Zarychta, Grillos, and Andersson 2020). As a cornerstone of equitable service delivery, bureaucratic professionalism and adherence to clear-cut rules and operating procedures can reduce politically motivated reasoning and implicit biases in SLB discretionary decisions that impact clientele (Brewer and Walker 2010; Cohen and Hertz 2020; Einstein and Glick 2017; Porter and Rogowski 2018; Zarychta, Grillos, and Andersson 2020). However, in the formulation of policy preferences, we argue that SLB will likely still be influenced by the rhetoric marketed by political elites that align with their political ideology. While SLB have been found to view welfare recipients as more deserving than the general public on average, we also know that bureaucrats have ideologies across the spectrum and are thus divided on the important public values that underlie the issue of administrative burden for clientele (Aberbach, Putnam, and Rockman 1981; Burden et al. 2012; Kallio and Kouvo 2015). On one hand, liberals may view policies increasing administrative burden as unjust because of the negative impact on program access for clients (Feldman and Zaller 1992). These liberal SLB may be particularly concerned with the impact of increasing burdens on the most marginalized clientele that would compromise the ability of public programs to enhance equity (Rudolph and Evans 2005). In contrast, conservative SLB likely see administrative burden policies as an effort to enhance program integrity and reduce fraud and waste in valuable taxpayer-funded programs (Williamson 2019). To conservatives, administrative burdens in the form of extensive eligibility requirements for clients likely align with the belief that people should have to work hard to access public programs (Feldman and Zaller 1992; Keiser and Miller 2020; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). In this way, these SLB would be identifying with the paternalistic rhetoric that insinuates that clients should be faced with challenges and will benefit from overcoming burden to “earn” program access (Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). Moreover, conservative ideology in the United States is defined by preferences for smaller or more submerged government and is associated with higher levels of support for policies that reduce overall direct spending, such as rationing access to expensive public programs (Haselswerdt and Bartels 2015). Therefore, we expect that the more conservative the SLB political ideology, the more likely SLB will be to support administrative burdens on clientele.

H1: Conservative street-level bureaucrats will be more likely to support policies that increase the administrative burden on clientele.

Drawing from political science literature, we also expect that ideology and perceptions of deservingness will shape how SLB justify their policy preferences regarding administrative burden (Jilke and Tummers 2018; Schneider and Ingram 1993). 4 A large body of literature demonstrates that perceptions of deservingness shape preferences regarding the allocation of policy benefits and burdens among elected officials and the public (Bell 2020; Doring 2018; Lawrence, Stoker, and Wolman 2013; Pierce et al. 2014; Schneider and Ingram 2019s). Recent developments in deservingness theory suggest that neediness, reciprocity—or the idea that clients are working hard to achieve self-sufficiency—and whether or not clients had control over their situation are important in predicting public perceptions of the unemployed (Meuleman, Roosma, and Abts 2020). Among SLB, “needed” and “earned” deservingness has also been shown to impact the prioritization of different clientele (Jilke and Tummers 2018). However, neither of these studies on the public or SLB considers the role of political ideology in shaping perceptions of deservingness (Jilke and Tummers 2018; Meuleman, Roosma, and Abts 2020). This is where political science literature can contribute to our understanding of the values, beliefs, and policy preferences of SLB regarding administrative burden. Previous literature on public opinion has found conservative Republicans to be more likely to distinguish between target groups on the basis of perceived deservingness when formulating policy preferences (Bell 2019a; Lawrence, Stoker, and Wolman 2013). In fact, recent studies suggest that political ideology is an important moderating factor in the relationship between perceived deservingness of target populations and public support for issues that are contentious across the ideological spectrum, such as welfare and affirmative action (Bell 2019a; Lawrence, Stoker, and Wolman 2013). Specifically, while public opinion among conservatives was significantly impacted by framing target populations as “high achieving,” public opinion among liberals was not impacted (Bell 2019a). Recent evidence on public support for TANF further supports this notion: While Republicans were significantly more supportive of TANF when they were exposed to information regarding the high levels of administrative burden in the eligibility requirements, Democrats were not significantly impacted (Keiser and Miller 2020). Drawing from this evidence on public opinion, we predict that, in the context of policies that increase administrative burden, conservative SLB will be more likely to reference perceptions of client deservingness in justifying beliefs about administrative burden, relative to liberal SLB.

H2: Conservative SLB will be more likely to reference client deservingness in justifying beliefs about administrative burden policies.

Administrative Burden in Oklahoma's Promise Program

We test our hypotheses in the context of Oklahoma's Promise program—a burdensome means-tested tuition-free college program in which SLB have significant discretionary power. Oklahoma's Promise program is an optimal case for examining SLB beliefs about administrative burden for two reasons: (1) there have been recent policy changes that have increased learning, compliance, and psychological costs on students and (2) the decentralized implementation structure creates significant discretionary power for SLB, whose values and beliefs influence client interactions with the administrative state (Bell 2019b). In our analysis, we include the most recent policy changes that increased administrative burden, including the addition of citizenship documentation requirements, annual income documentation requirements, and additional academic merit requirements, as well as the elimination of financial support for remedial education courses. By adding academic merit standards—known as satisfactory academic progress standards—and eliminating aid for remedial courses, policymakers increased the learning costs and compliance costs on students. Moreover, by adding annual income checks and citizenship documentation requirements, policymakers increased psychological burdens for low-income students who face the stigma of taking recurring means tests and excluded as undocumented students from eligibility. Together, these policy changes have intensified the burdens students face in the application process, creating what is perhaps one of the most burdensome financial aid programs in the nation. In table 1, we present the full list of requirements that were in place at the time we conducted our survey in 2018.

| Type of Requirement | Specific Requirements |

| Academic requirements in high school |

|

| Conduct requirements |

|

| Income verification |

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Academic requirements in college |

|

| Restrictions on aid while in college |

|

The program includes not only formal administrative hurdles but also potential informal barriers created by SLB who have discretionary power to influence client–state interactions. The process of compliance certification and program advertisement in Oklahoma's Promise program is highly decentralized. The Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education (OSRHE), the statewide administrator of Oklahoma's Promise program, does not conduct individual client outreach and relies on SLB to disseminate information about the program when students are in 8th, 9th, or 10th grade. OSRHE also relies on SLB to assist students in the application process, and, most importantly, certify compliance with the programmatic requirements upon high school graduation (Bell and Smith 2019). In the first phase of the program, students in 8th, 9th or 10th grade must submit an on-time, complete application or face disqualification. This initial application process includes a five-page form with required income verification and a completed agreement that the student will earn at least a 2.5 grade point average (GPA) in the 17-unit core curriculum, attend school regularly, complete homework, and refrain from substance abuse and criminal delinquent acts or face disqualification. In this initial process, SLB control whether students have information on the program in time to apply, receive personal assistance with the application process, and face additional paperwork barriers through verification processes (Bell 2019b; Bell and Smith 2019). While students are in high school, SLB are responsible for confirming that they are meeting the curriculum, GPA, and conduct requirements. Upon high school graduation, the SLB certifies whether the student is compliant with these requirements. While some SLB take a proactive approach to supporting students in high school, others serve primarily as gatekeepers (Bell 2019b; Bell and Smith 2019). For instance, because OSRHE did not provide a consistent and uniform definition of “substance abuse and criminal delinquent acts” until 2018, each SLB had the authority to determine what this rule represented and certify compliance accordingly. In fact, in a case in 2017, Bailey White—who was the valedictorian of her high school—sued Pond Creek-Hunter High School over being denied Oklahoma's Promise because of the counselor's discretionary decision to certify her as noncompliant with program requirements due to a non-adjudicated shoplifting incident that occurred prior to her enrollment in Oklahoma's Promise. Ultimately, OSRHE overturned the counselor's decision and updated the administrative rules to provide clearer definitions related to substance abuse and criminal delinquent acts (Bell 2019b; Felder 2017). This is one among many examples of SLB in Oklahoma's Promise program wielding discretionary power to either alleviate or exacerbate burden in the application process. In fact, in line with the literature demonstrating the importance of values and beliefs in shaping uses of discretionary power by SLB (e.g., Brodkin and Majmundar 2010; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011; Watkins-Hayes 2011), a recent study found that role perceptions and partisanship of SLB shape the use of discretion and program access in Oklahoma's Promise program (Bell 2019b; Bell and Smith 2019). More broadly, research on school counselors in other settings has found that higher staffing levels, use of discretion in communication types, and intensive college counseling efforts are associated with positive educational outcomes such as college application and enrollment (Castleman and Goodman 2018; Cunha, Miller, and Weisburst 2018; Hurwitz and Howell 2014; Tang and Ng 2019; Welsch and Winden 2019). Therefore, it is essential to better understand the relevant values and beliefs about administrative burden among SLB who wield significant discretionary power to shape client experiences of the administrative state.

Data Description

To investigate SLB policy preferences and beliefs about administrative burden, we conducted a statewide online survey in May 2018 with the help of OSRHE staff, who sent the recruitment email to the listserv that OSRHE staff maintain of counselors at high schools and some nonprofits involved in the street-level implementation of Oklahoma's Promise program. We obtained 226 completed surveys with details on demographic characteristics, task environment, and beliefs about administrative burden. Ideally, we would be able to compare the individual characteristics of our sample to the broader population of SLB involved with Oklahoma's Promise; however, administrative data on this population's demographic characteristics do not exist. Therefore, we provide the best possible comparison in appendix A where we compare the schools included in our survey sample with the full sample of schools in Oklahoma based on data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Through this comparison, we find that our survey sample is slightly more urban and has higher total enrollments than the statewide population of schools. In addition, our sample appears to have slightly lower percentages of free and reduced-price lunch (FRL) students and a higher student to teacher ratio.

In table 2, we describe the survey data set, and in table 3 we present the measurement of our key independent and dependent variables in our analysis.

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Male | 224 | 0.084 | 0.278 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | 224 | 2.212 | 0.805 | 1 | 4 |

| Education | 224 | 6.911 | 0.551 | 2 | 8 |

| Racial/Ethnic identity | |||||

| White | 224 | 0.783 | 0.413 | 0 | 1 |

| Black or African American | 224 | 0.022 | 0.147 | 0 | 1 |

| Native American | 224 | 0.084 | 0.278 | 0 | 1 |

| Hispanic | 224 | 0.080 | 0.271 | 0 | 1 |

| Political Ideology | |||||

| Ideology | 224 | 4.628 | 1.650 | 1 | 7 |

| Task Environment | |||||

| Collaboration with nonprofit organizations | 224 | 0.133 | 0.340 | 0 | 1 |

| Years in position | 224 | 3.053 | 0.887 | 1 | 4 |

| Time able to spend on college preparation | 224 | 45.290 | 24.166 | 0 | 100 |

| Resources/School family income comparison | 224 | 3.539 | 0.895 | 1 | 5 |

| Beliefs about administrative burden | |||||

| Combined burden index | 224 | 14.375 | 3.402 | 4 | 20 |

| Support for additional income checks | 224 | 3.504 | 1.361 | 1 | 5 |

| Support for SAP requirement | 224 | 4.456 | 0.864 | 1 | 5 |

| Support for citizenship requirement | 224 | 3.358 | 1.491 | 1 | 5 |

| Support for restriction on remedial courses | 224 | 3.212 | 1.445 | 1 | 5 |

| Justifications for administrative burden beliefs | |||||

| Deservingness | 224 | 0.455 | 0.499 | 0 | 1 |

| Class consciousness | 224 | 0.147 | 0.355 | 0 | 1 |

| Equity | 224 | 0.308 | 0.463 | 0 | 1 |

| Fraud | 224 | 0.152 | 0.359 | 0 | 1 |

| Professional challenges | 224 | 0.081 | 0.273 | 0 | 1 |

- Abbreviation: SAP, satisfactory academic progress.

| Variable | Question Wording | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Beliefs about Administrative Burden | Changes made to the Oklahoma's Promise scholarship program over time are described below. Do you support or oppose these changes?

|

1 – Strongly Oppose 2 – Somewhat Oppose 3 – Neither Support nor Oppose 4 – Somewhat Support 5 – Strongly Support |

| Ideology | On a scale of political ideology, individuals can be arranged from strongly liberal to strongly conservative. Which of the following categories best describes your views? |

1 – Strongly Liberal 2 – Liberal 3 – Slightly Liberal 4 – Middle of the Road 5 – Slightly Conservative 6 – Conservative 7 – Strongly Conservative |

| Education | What is the highest level of education you have COMPLETED? |

1 – Less than High School 2 – High School / GED 3 – Vocational/Technical Training 4 – Some College — NO degree 5 – 2-year College / Associate's Degree 6 – Bachelor's Degree 7 – Master's degree 8 – Doctorate/PhD/ JD(Law)/MD |

| Income | Was the estimated annual income for your household in 2017: |

1 – Less than $50,000 2 – At least $50,000 but less than $100,000 3 – At least $100,000 but less than $150,000 4 – $150,000 or more |

| Years in Position | How long have you been working in your position? |

1 – Less than 1 year 2 – 1-3 years 3 – 4-10 years 4 – More than 10 years |

| School Family Income Comparison | When compared to other schools in your community, do you think the average income of families at your school is lower, higher, or about the same? |

1 – Much higher 2 – Somewhat higher 3 – About the same 4 – Somewhat lower 5 – Much lower |

Table 2 shows that there is variation in the degree of support for the policy changes passed by the state legislature that increase administrative burden on students. While the average respondent somewhat supported the satisfactory academic progress (SAP) requirement, the average response for the other three policies were neutral, and the policy with the most significant variation across respondents was the citizenship documentation requirement. Table 2 also reveals that the SLB in our sample reflect the demographic characteristics of the state apart from gender. Our sample is only 8 percent male, which is not surprising given that high school counselors across the nation are predominantly female. The rest of the demographic characteristics reflect the state of Oklahoma with most respondents identifying as white, conservative, and middle income. The task environments vary across respondents, with most SLB working in a public or private high school and eight respondents working for nonprofits or higher education institutions in the TRIO or GEARUP programs. 5 Moreover, 13 percent of respondents indicated that they partner with community nonprofit organizations. Finally, we asked respondents to answer whether they thought the average family income of their school was higher or lower than other schools, and most respondents replied that they thought families in their school had slightly lower income.

In addition to this quantitative data, the survey also included rich open-ended responses (n = 276) where SLB were asked to justify their stated beliefs regarding administrative burden. In our qualitative findings section, we utilize these open-ended responses to explore the main values and themes that are salient in evaluations of administrative burden policies.

Does Political Ideology Shape Support for Administrative Burden Policies among Street-Level Bureaucrats?

We leverage multiple complementary analytical approaches to estimate the relationship between political ideology and support for administrative burden. First, we collapse the four separate policy support variables into an index that ranges from 4 (strongly oppose all four policies) to 20 (strongly support all four policies) and estimate the impact of ideology on this burden support index. 6 Next, we provide a more nuanced analysis in which we estimate the relationship between political ideology and support for each of the four administrative policies separately. In each of these specifications, we standardize explanatory variables to enhance the comparability of the point estimates.

In table 4, we present the results from the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis in which we predict the level of support on the administrative burden index as a function of political ideology and our set of covariates. To test the robustness of our findings, we include a specification with and without county fixed effects. The county fixed effects included in Model 2 increase model fit and account for the potential influence of rural and urban geographies and the corresponding ideological makeups of the communities within which SLB are situated (Stensöta 2012). Across both model specifications, we find that political ideology is the most important predictor of support for administrative burden in our sample, which supports hypothesis 1. Even after we account for cross-county variation, we find that the more conservative the SLB, the more likely these bureaucrats are to support administrative burden. In terms of magnitude, each one standard deviation unit increase on the ideology scale is associated with a 0.9–1.0 point increase on the 17-point burden support index. In practice, this means that going from middle of the road to strongly conservative would increase the level of support for burden by 1.62–2.13 on the 17-point support index.

| Model 1: No County Fixed Effects | Model 2: Add County Fixed Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | Standard Error | p-value | Coef | Standard Error | p-value | |

| Ideology | 0.914*** | (0.23) | .000 | 1.170*** | (0.29) | .000 |

| White | 0.283 | (0.23) | .214 | −0.063 | (0.32) | .845 |

| Education | 0.148 | (0.44) | .737 | 0.652 | (0.44) | .144 |

| Income | 0.175 | (0.21) | .546 | 0.163 | (0.24) | .502 |

| Male | −0.212 | (0.23) | .365 | −0.519** | (0.19) | .007 |

| Years in position | 0.395 | (0.23) | .092 | 0.446 | (0.29) | .132 |

| Collaboration with nonprofits | −0.03 | (0.24) | .931 | −0.161 | (0.35) | .642 |

| Percentage of time able to spend on college preparation | 0.119 | (0.27) | .663 | 0.314 | (0.27) | .243 |

| School family income Comparison | −0.259 | (0.22) | .290 | −0.082 | (0.33) | .804 |

| Constant | 14.09*** | (0.52) | .000 | 12.50*** | (0.66) | .000 |

| Observations | 224 | 224 | 177 | 177 | ||

| County fixed effects | X | X | ||||

| R-squared | 0.148 | 0.148 | 0.591 | 1.591 | ||

- Note: All explanatory variables are standardized. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered by school.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

Next, we present table 5, in which we test the role of ideology in shaping support for each of the policy changes that contributed to administrative burden in Oklahoma's Promise program. We include both covariates and county fixed effects in each model to increase model fit and isolate the relationship between political ideology and support for administrative burden. We find further support for hypothesis 1 in table 5—conservative SLB in our sample were more likely to support the additional income checks, the citizenship requirement, and the restrictions on funding for remedial courses. To provide an easily interpretable estimate of magnitude, we estimate the impact of political ideology on dichotomous dependent variables capturing whether or not the SLB somewhat or strongly supported the policies in appendix table B2. In these models, we find that a one unit standard deviation increase on the ideology scale is associated with a 11.5 percentage point increase in support for additional income checks, a 11.5 percentage point increase in support for the citizenship requirement, and a 9.1 percentage point increase for the remedial education restriction. However, ideology was insignificantly related to the likelihood of supporting the addition of Satisfactory Academic Progress (SAP) standards. This is likely because adding SAP standards was not as polarizing in the rhetoric among political elites when compared with each of the other changes. Nevertheless, we find that ideology was the strongest factor predicting support for three of the four specific administrative burden policies in Oklahoma's Promise program, providing empirical support for hypothesis 1 (Herd and Moynihan 2018).

| Model 1: Support for Additional Income Checks | Model 2: Support for Adding SAP Standards | Model 3: Support for Citizenship Requirement | Model 4: Support for Restriction on Remedial Courses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | SE | p-value | Coef | SE | p-value | Coef | SE | p-value | Coef | SE | p-value | |

| Ideology | 0.326* | (0.131) | .014 | 0.086 | (0.067) | .200 | 0.354* | (0.159) | 0.028 | 0.404** | (0.149) | .008 |

| White | 0.047 | (0.158) | .768 | −0.051 | (0.086) | .553 | 0.002 | (0.162) | 0.992 | −0.06 | (0.140) | .670 |

| Education | 0.366 | (0.187) | .053 | 0.068 | (0.155) | .663 | 0.107 | (0.221) | 0.630 | 0.111 | (0.255) | .665 |

| Income | 0.195 | (0.101) | .056 | 0.023 | (0.108) | .833 | −0.084 | (0.163) | 0.607 | 0.029 | (0.125) | .814 |

| Male | −0.127 | (0.125) | .311 | −0.199 | (0.111) | .075 | −0.166 | (0.147) | 0.262 | −0.027 | (0.142) | .847 |

| Years in position | 0.144 | (0.121) | .236 | 0.106 | (0.064) | .099 | −0.073 | (0.175) | 0.676 | 0.269 | (0.140) | .057 |

| Collaboration with nonprofits | 0.025 | (0.148) | .868 | −0.104 | (0.118) | .379 | −0.035 | (0.145) | 0.812 | −0.047 | (0.112) | .676 |

| Percentage of time spent on college prep | 0.219* | (0.109) | .048 | 0.004 | (0.074) | .954 | 0.031 | (0.159) | 0.844 | 0.059 | (0.135) | .663 |

| School family income comparison | 0.014 | (0.150) | .923 | −0.051 | (0.098) | .606 | −0.07 | (0.202) | 0.730 | 0.024 | (0.172) | .891 |

| Constant | 0.858* | (0.353) | .016 | 4.059*** | (0.197) | .000 | 4.626*** | (0.404) | 0.320 | 2.959*** | (0.426) | .000 |

| County fixed Effects | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Observations | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.572 | 0.572 | 0.431 | 0.431 | 0.384 | 0.384 | 0.486 | 0.486 | ||||

- Abbreviation: SAP, satisfactory academic progress. Note: All explanatory variables are standardized. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered by school.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

How Does Ideology Shape Justifications for Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Beliefs about Administrative Burden?

In our exploratory qualitative analysis of open-ended survey responses, we employ open and axial coding methods to identify key narratives that form the foundations of counselors' beliefs regarding administrative burden (Corbin and Strauss 2007; Creswell 2009). Following Strauss and Corbin's (1998) open coding process, we broke down the data from open-ended responses into manageable chunks and examined each chunk line by line in terms of the concepts present. A list of initial codes was developed, and we examined the characteristics, or properties, of each code and the range, or dimension, along which these characteristics varied (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). Through axial coding, we reviewed the initial list of codes developed and collapsed related concepts to develop a more succinct list of five key themes: deservingness, barriers to equity, fraud/waste/abuse, professional challenges, and class consciousness.

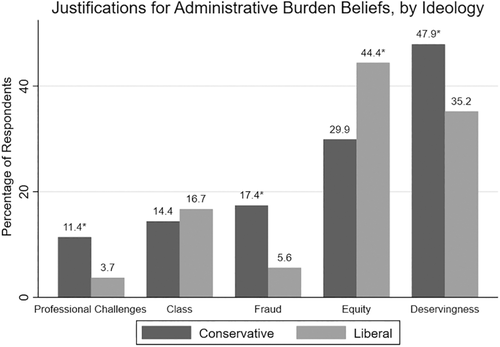

For each of these themes, two of the authors independently coded dichotomous variables indicating whether the open-ended response of each SLB response utilized the theme in justifying their beliefs about administrative burden policies. Therefore, our coding scheme recognizes and captures when there is more than one theme in a single open-ended response, which occurred in approximately 30 percent of the responses. Initial intercoder agreement percentages ranged from 59 percent for professional values and experience to 65 percent for deservingness, 66 percent for class consciousness, 77 percent for equity, and 87 percent for fraud/waste/abuse, and all disagreements were reconciled. In figure 1, we present the percentage of respondents that utilized each theme in the justification of their stated preferences on administrative burden for slightly to strongly conservative SLB (n = 119) and liberal SLB (n = 59). After conducting difference of means tests, we find that conservative SLB were significantly more likely to reference deservingness, fraud, and professional challenges when compared to liberal SLB. In contrast, liberal SLB were more likely to reference social equity than conservative SLB.

Justifications for Administrative Burden Beliefs by Ideology

Note: * indicates significant difference p < .05 in a difference of means test.

To provide a window into what each theme looked like in the qualitative data, we present a randomly selected sample of the open-ended responses for our separate samples of conservatives and liberals in table 6. In our following analysis, we also supplement these randomly selected quotes with additional information-rich responses that capture common justifications and add richness and detail to the viewpoints reflected in table 6.

| Theme | Quote |

| Deservingness | Conservative |

|

|

| Liberal | |

|

|

| Social equity | Conservative |

|

|

| Liberal | |

|

|

| Fraud | Conservative |

|

|

| Liberal | |

|

|

| Professional challenges | Conservative |

|

|

|

|

| Class consciousness | Conservative |

|

|

| Liberal | |

|

In line with our expectations in hypothesis 2, the most dominant theme was perception of deservingness, and conservative SLB in our sample were more likely to draw on deservingness to explain their beliefs regarding administrative burden policy (Bell 2019a). Interestingly, this theme appeared either with positive or negative valence, with predominantly conservative SLB utilizing deservingness to justify their support for administrative burden and liberal SLB drawing on deservingness to explain why they opposed administrative burden. Among conservative SLB, support for administrative burden was justified by arguing that these policies prevented “undeserving” students from gaining access to a valuable taxpayer benefit (Schneider and Ingram 2012). For instance, one respondent succinctly summarized the views of many SLB in our survey, arguing that “it's a scholarship, not a handout,” suggesting that low-income students and families should have to work hard to earn the benefits (Jilke and Tummers 2018; Soss, Fording, and Schram 2011). This sentiment was especially prevalent in justifications for the citizenship documentation and remedial education, where SLB argued that children of undocumented immigrants and students who need remedial courses should not be able to gain access to the program benefits. For example, one conservative respondent supported eliminating eligibility for undocumented students because “we work hard for our money to put our kids through school and immigrants come to the USA and get everything for free.… [it] is not fair because if we went to their country, we would not get the same support.” In this view, access to Oklahoma's Promise should be available only to U.S. citizens; otherwise the program would become a “handout” to undocumented students.

We have an excellent student who recently had her OK Promise scholarship taken from her because she is a DACA student. This student deserves the money and her grades prove it. Now she is struggling to figure out how to afford college.

According to this respondent, the student demonstrated “earned” deservingness because she was an excellent student with good grades, but because of her immigration status—which is out of her control—the student was denied the scholarship. Because the circumstances were outside the student's control and the student demonstrated reciprocity through earning good grades, the citizenship policy is viewed as an unjust barrier to access, which aligns with studies on the deservingness perceptions of the unemployed (Meuleman, Roosma, and Abts 2020).

Students who qualify often come from homes that neither parent has complete[d] college therefore they usually have not had much parental support. By not paying for remedial classes it leaves students, who are already at a disadvantage, with yet another obstacle (finances) to overcome….The additional income checks just creates more paperwork for everyone involved.

These changes are designed to eliminate people from the program and thus it places an undue barrier to income challenged students. Oklahoma's Promise was designed to give more opportunities to our under-privileged students, not less.

According to this respondent, the policy changes that have been implemented since the inception of Oklahoma's Promise in 1992 have not served to expand access to higher education opportunities for low-income students; rather, the policies have placed increasing burdens on marginalized students that generally lack the support system needed to navigate a complex application process.

In contrast to this equity lens, many supporters of policies increasing administrative burden stated their concern regarding fraud, waste, and abuse to justify their support for additional income checks, citizenship requirements, and conduct requirements. Figure 1 demonstrates that this theme was predominantly utilized by conservative SLB, but some liberal SLB also expressed concern about fraud, waste, and abuse. The most common response in this category was the notion that without additional administrative burdens, clients would “cheat the system.” In fact, one conservative SLB suggested that “more checks should be required for compliance to OK Promise. That keeps everyone honest!” A specific recurring example of students cheating the system was families that receive tax deductions for their farms. For example, one SLB argued that the current income verification system is unjust because “there are many families who are claiming less because of farm deductions (multi-million dollar land owners living in large new homes and new cars) and they qualify for OK Promise. Many, many of these…NOT RIGHT!” This SLB goes on to argue that it is also unjust that students who “have had tickets like DUI's or alcohol related tickets that eventually get worked off because of probation and community service still get to keep OK Promise. NOT RIGHT!” To these SLB, administrative burden increases fairness and program integrity, effectively ensuring that only truly “deserving” students—because of their financial need and ability to overcome administrative hurdles—are the ones to gain access to a scholarship program subsidized with taxpayer money.

It seems to me that middle class America has completely been left out when it comes to scholarships and financial aid. I have seen the frustration of many students that work hard to maintain good grades and achieve high standards and receive nothing. In return they accumulate high student debt. These are the ones that will finish college and contribute to society.

This observation highlights the indignation felt by many middle-class families and students who are stuck between being unable to qualify for need-based grants and scholarships and being unable to afford the rising costs of college attendance. Furthermore, the reference to middle-class students as being “the ones that will finish college and contribute to society” adds an extra layer regarding the concept of deservingness and stereotypes related to the types of students who will become contributing members of a normative society. A liberal respondent also demonstrated similar beliefs about the lack of access to Oklahoma's Promise for middle-class students and families, stating “I think the middle class earners who pay their taxes and support their families get cheated because they have to go into incredible debt to pay college expenses because they don't qualify for Oklahoma's Promise. Often they are just over the qualification limits.” We see a similar feeling of class injustice here in that middle class students are “cheated” out of the scholarship because their families earn too much and put the students over the income limit for Oklahoma's Promise and more than likely they will need to take out student loans in order to pay for a college education (Goldrick-Rab 2016).

Since many of our students will be first generation college students and 70 percent of our school receives free/reduced lunch our students need more academic support. Unfortunately much of the counselors’ time is spent on daily duties (2 hours EVERY DAY), testing during peak seasons, we cannot possibly help all of our kids in a timely manner.

These professional challenges resemble the task environments in other policy areas, such as welfare and criminal justice, where conditions of resource scarcity create an environment in which SLB must make tough decisions regarding which clients are prioritized (Maynard-Moody and Musheno 2003; Watkins-Hayes 2011). In making these discretionary decisions, SLB values and beliefs are of paramount importance and influence the ability of students to access programs like Oklahoma's Promise (Bell and Smith 2019).

Conclusion

Scholars studying administrative burden have called for more attention to the relationship between administrators and burdens as well as the distinction between reasonable and unreasonable burdens (Moynihan, Herd, and Harvey 2015). However, extant literature has yet to investigate the policy preferences of SLB regarding policies that make application processes more burdensome for clientele. Because SLB have bureaucratic discretion that may affect client experiences of programs, their values, beliefs, and preferences are key to understanding how administrative burdens will impact democratic outcomes (Bell and Smith 2019). Ultimately, even if state legislatures enact additional administrative burdens on clientele, it is in the hands of SLB to determine how burdensome interactions are for clients applying for public programs. Additionally, SLB, in this case counselors, can have major effects on client outcomes, such as college readiness, college choice, and persistence (Bettinger and Evans 2019; Castleman and Goodman 2018; Cunha, Miller, and Weisburst 2018; Hurwitz and Howell 2014; Mulhearn 2019; Welsch and Winden 2019). Therefore, we argue that it is imperative to better understand how SLB interpret and justify beliefs regarding administrative burden policies. We examine these dynamics in the context of a decentralized, burdensome statewide means-tested financial aid policy—Oklahoma's Promise—that allocates significant discretionary power to SLB to determine the level of administrative burden clients face in the application process (Bell and Smith 2019).

Our first-order findings reveal that there is significant variation in the level of support for administrative burden policies and that the political ideologies of SLB in our sample meaningfully influence how they interpret policies and formulate preferences. Across our model specifications, we find that conservative SLB supported higher levels of administrative burden. Conservative SLB were significantly more likely to support citizenship documentation requirements, restrictions on remedial courses, and adding annual income checks. These findings suggest that SLB who wield the power to shape client interactions with the administrative state have varied interpretations of policies that increase administrative burden and that ideology is an important predictor of these beliefs.

Our exploratory qualitative analysis revealed five themes salient in SLB justifications of beliefs about administrative burden—deservingness, social equity, fraud/waste/abuse, class consciousness, and professional challenges. While class consciousness cut across the ideological spectrum, conservative SLB in our sample were more likely to reference deservingness, fraud/waste/abuse, and professional challenges and liberal SLB were more likely to reference social equity in their formulation of preferences regarding policies that increase administrative burden in Oklahoma's Promise. Two main narratives emerged from these justifications—on one hand, predominantly liberal SLB argued that the policies created undue barriers to access and had negative effects on equity. There was also an opposing narrative in which predominantly conservative SLB justified administrative burden as playing a crucial part in preventing “undeserving” clientele from accessing the program or “cheating the system.” The reference to deservingness in justifying administrative burden aligns with literature on the social construction of target populations, which finds that policymakers and the public are more likely to disproportionately allocate benefits to positively constructed, powerful groups and burdens to negatively constructed, less powerful groups (Schneider and Ingram 2012). Moreover, the fact that conservatives are more likely to be concerned about the deservingness of target populations aligns with emerging research suggesting that conservatives are more likely to formulate policy preferences on the basis of the perceptions of deservingness of the target population (Bell 2019a; Lawrence, Stoker, and Wolman 2013). These findings suggest that, in the context of Oklahoma's Promise program, the narratives on the front lines of government regarding the appropriateness and normative valence of administrative burden varies across SLB according to ideological beliefs. In future studies, scholars should pursue experimental survey designs where we can test the connection between socially constructed target groups, ideology, and support for administrative burden in application processes explicitly. This area for future research would address the potential for within-SLB variation in preferences and uses of discretion in the realm of administrative burden as a result of shifting socially constructed client groups—a source of variation not captured in this article.

It should be noted that the results of this study apply to our sample of SLB, which may or may not reflect the overall population of SLB working on Oklahoma's Promise program. Additionally, our results may or may not translate to other countries and policy areas. The political and economic context of Oklahoma's Promise program creates an ideal venue for studying administrative burden and street-level bureaucrats, but one could imagine that the results may be different if tested in a state or country with a significantly different ideological makeup. However, it is also possible that political ideology and perceptions of deservingness would be key predictors of beliefs about administrative burden, regardless of the political and economic context. Moving forward, scholars should examine the extent to which political ideology and perceived deservingness predicts beliefs about burden in other political and economic contexts to provide further evidence on this question.

Implications for Practice

SLB are in the midst of political battles over the balance of program integrity and equity in public programs, wielding significant discretionary power to either alleviate or intensify the administrative burden experienced by program beneficiaries (Bell and Smith 2019; Lipsky 2010). According to our results, while some SLB acknowledge the potential for administrative burden policies to widen equity gaps and undermine political efficacy, many conservative SLB support policy changes that create additional administrative hurdles for clientele. As we move forward, there are multiple interventions that practitioners should consider in managing SLB with divergent political ideologies and policy preferences regarding administrative burden. First, public managers could implement an information campaign that informs SLB about the potential impacts of administrative burden on clients and test whether this information changes policy preferences. A field experiment that manipulates exposure to information on the implications of additional hurdles in the application process has the potential to change SLB evaluations of administrative burden, especially for conservatives (Keiser and Miller 2020). Second, the administrators could conduct focus groups with SLB and utilize these focus groups to formulate a set of standard operating procedures that could reduce the potential for implicit biases and motivate uniform guidelines to policy implementation at the front lines (Wilson 1887). This strategy would allow for SLB from various ideological backgrounds to work together in a professional environment toward better understanding the challenges administrative burden creates for marginalized clientele and encourage collaboration in the pursuit of developing consistent strategies that help students overcome common barriers to program access.

Notes

Appendix A: Representativeness of Survey Sample

After attempting to find demographic data on all street-level bureaucrats working on Oklahoma's Promise implementation in two different state agency databases, we found that this information does not exist and would require a separate survey that the state agency was unwilling to administer. However, we leverage data from the National Center for Education Statistics and present what the high schools included in our survey sample looked like in the 2017–2018 school year to compare how representative our sample is relative to the statewide population. In table A1, we find that our survey sample is slightly more urban and has higher total enrollments than the statewide population of schools. In addition, our sample appears to have slightly lower percentages of FRL students and a higher student-to-teacher ratio. These are important differences in the task environment, but for the purposes of this article, the inclusion of county fixed effects should control for any influence of rural/urban school environments. Nevertheless, these differences in the sample could potentially affect the generalizability of the findings, though we doubt that school-level factors would have a significant moderating influence on the role of political ideology in shaping beliefs about administrative burden.

| Variables | N Schools | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statewide Population of High Schools | |||||

| Total enrollment | 466 | 388.96 | 552.89 | 21 | 3,778.000 |

| Percent minority | 466 | 0.44 | 0.186 | 0.048 | 0.996 |

| Urban | 466 | 0.14 | 0.342 | 0 | 1.000 |

| FTE teachers | 460 | 24.09 | 28.59 | 0.59 | 194.500 |

| Charter | 466 | 0.03 | 0.165 | 0 | 1 |

| Percent FRL | 459 | 0.595 | 0.184 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Survey Sample High Schools | |||||

| Total enrollment | 182 | 538.54 | 688.78 | 24 | 3,778 |

| Percent minority | 182 | 0.46 | 0.178 | 0.056 | 0.996 |

| Urban | 182 | 0.18 | 0.386 | 0 | 1 |

| FTE teachers | 182 | 32.35 | 35.28 | 0 | 1 |

| Charters | 182 | 0.02 | 0.128 | 0 | 1 |

| Percent FRL | 178 | 0.558 | 0.176 | 0.071 | 1 |

- Note: The smaller n size in the survey sample of high schools compared to the analysis tables in the main text is due to missing data in the identification of the schools where the counselors worked, or the instances where there was more than one counselor working at the same school.

Appendix B: Robustness Checks

| Model 1: No County FE | Model 2: Adding County FE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | p-value | Coefficient | SE | p-value | |

| Party ID—Republican | 0.630** | (0.23) | .007 | 0.819** | (0.31) | .009 |

| White | 0.283 | (0.23) | .218 | 0.001 | (0.35) | .997 |

| Education | 0.19 | (0.42) | .649 | 0.625 | (0.55) | .254 |

| Income | 0.151 | (0.23) | .518 | 0.094 | (0.27) | .731 |

| Male | −0.167 | (0.25) | .497 | −0.407 | (0.24) | .086 |

| Years in position | 0.421 | (0.23) | .070 | 0.529 | (0.28) | .057 |

| Collaboration with nonprofits | −0.015 | (0.25) | .952 | −0.042 | (0.40) | .917 |

| Percentage of time spent on college preparation | 0.083 | (0.27) | .758 | 0.352 | (0.26) | .182 |

| School family income comparison | −0.302 | (0.25) | .236 | −0.282 | (0.31) | .363 |

| Constant | 14.59 | (0.23) | .000 | 13.16*** | (0.66) | .000 |

| Observations | 224 | 224 | 224 | 178 | 178 | 178 |

| County fixed effects | X | X | X | |||

| R-squared | 0.10 | 0.10 | .10 | 0.56 | 0.56 | .56 |

- All explanatory variables are standardized. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered by school.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

| Model 1: Support for Additional Income Checks | Model 2: Support for Adding SAP Standards | Model 3: Support for Citizenship Requirement | Model 4: Support for Restriction on Remedial Courses | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef | Standard Error | p-value | Coef | Standard Error | p-value | Coef | Standard Error | p-value | Coef | Standard Error | p-value | |

| Ideology | 0.115* | (0.048) | .018 | 0.008 | (0.014) | .556 | 0.115* | (0.044) | 0.011 | 0.091 | (0.052) | .079 |

| White | −0.009 | (0.056) | .874 | −0.017 | (0.032) | .597 | 0.017 | (0.049) | 0.733 | −0.019 | (0.051) | .715 |

| Education | 0.066 | (0.069) | .337 | 0.005 | (0.032) | .885 | 0.051 | (0.069) | 0.461 | −0.012 | (0.094) | .898 |

| Income | 0.058 | (0.039) | .148 | −0.029 | (0.029) | .317 | 0.017 | (0.060) | 0.778 | −0.007 | (0.043) | .874 |

| Male | −0.022 | (0.041) | .597 | −0.047 | (0.037) | .200 | −0.062 | (0.054) | 0.251 | 0.001 | (0.050) | .980 |

| Years in position | 0.066 | 0.049 | .178 | 0.042 | (0.025) | .093 | 0.011 | (0.061) | 0.859 | 0.123* | (0.050) | .015 |

| Collaboration with nonprofits | −0.001 | (0.061) | .992 | −0.038 | (0.037) | .313 | 0.01 | (0.049) | 0.834 | −0.018 | (0.050) | .721 |

| Percentage of time spent on college prep | 0.063 | (0.037) | .088 | 0.003 | (0.026) | .907 | −0.015 | (0.054) | 0.784 | −0.029 | (0.048) | .542 |

| School family income Comparison | 0.024 | (0.053) | .659 | −0.001 | (0.032) | .989 | 0.000 | (0.064) | 0.999 | 0.004 | (0.067) | .953 |

| Constant | −0.04 | (0.113) | .724 | 1.017*** | (0.049) | .000 | 0.888*** | (0.139) | 0.000 | 0.066 | (0.164) | .687 |

| County fixed effects | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Observations | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | ||||

| R-squared | 0.553 | 0.553 | 0.479 | 0.479 | 0.419 | 0.419 | 0.462 | 0.462 | ||||

- Note: All explanatory variables are standardized. Each dependent variable was collapsed into a dichotomous indicator coded as 1 = strongly or somewhat support 0 = neutral or somewhat or strongly oppose. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered by school. SAP stands for satisfactory academic progress.

- *** p < .001.

- ** p < .01.

- * p < .05.

Biographies

Elizabeth Bell is an assistant professor of Public Administration in the Department of Political Science at Miami University in Ohio. Her research examines how public managers operate within politically designed policy regimes to shape inequality. The goal of her work is to improve the ability of government programs to meet policy goals and alleviate inequality in college access and success. Elizabeth's work has been published in journals such as The Journal of Politics, Public Administration Review, and American Educational Research Journal.

Email: [email protected]

Ani Ter-Mkrtchyan is an assistant professor at the Department of Government at New Mexico State University. Her work has been published in various journals, and her main research interests center around the questions of citizen–state interactions, public trust, public and nonprofit accountability, bureaucratic responsiveness, and performance measurement and transparency. She is also passionate about environmental policy and has previously worked as a practitioner in the international non-governmental organizations sector.

Email: [email protected]

Wesley Wehde is an assistant professor at East Tennessee State University in the Department of Political Science, International Affairs, and Public Administration. His research interests include environmental and natural hazards policy preferences, federalism, emergency management, and research methods. His previous work can be found in Policy Studies Journal, Review of Policy Research, and Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy.

Email: [email protected]

Kylie Smith is a doctoral candidate in the College of Education at Jeannine Rainbolt's Educational Leadership and Policy Studies Department at the University of Oklahoma. She also serves as the vice chancellor for administration for the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education, Oklahoma's coordinating board for the state's 25 public colleges and universities. Her research interests focus on the role that financial aid policies and programs play in addressing inequities in college choice, access, and success.

Email: [email protected]