Contract Renewal in Urban Water Services, Incumbent Advantage, and Market Concentration

Abstract

Contract renewal with the incumbent is common practice in the contracting-out of public services. It could, however, affect competition by reinforcing trends towards market concentration. This article contributes empirical evidence on the determinants of the result of public tenders for the renewal of private provision of urban water services. A dataset with information on 215 public tenders held in Spain between 2008 and 2019 is employed. The methodology is based on logistic regression techniques. The findings indicate that incumbent size does not play a role in the probability of alternation between service providers. Furthermore, competition (proxied by the number of bidders) and transparency in managing public tenders both increase the likelihood of alternation between providers. Lastly, the estimates suggest that larger municipality size and discretionary power of entrenched political parties might also play a role in favoring incumbent contract renewal.

Evidence for Practice

- More bidders and higher transparency make alternation more likely in public tenders for the renewal of contracts for the private provision of urban water services. Conversely, discretionary power of well-established political parties and large municipality size make incumbent renewal more likely.

- Incumbent size and their share of the private market for urban water provision do not play a role in explaining the result of renewal public tenders.

- Promoting competition in tenders and boosting transparency in the management of contracts are critical for ensuring the achievement of public interest goals in the contracting-out of urban water services.

It is common practice in developed economies to contract out the provision of municipal services, including some social services, environmental conservation, street cleaning, and water supply or waste collection and treatment. A large body of literature has addressed the different forms of contracting-out (Bel and Gradus 2018), and the factors that explain such decisions made by local governments (reviews are provided by Bel and Fageda 2009 and Wassenaar, Groot, and Gradus 2013). While city councils always retain responsibility for ensuring the provision of local services, delivery concessions are normally awarded through public tenders and are limited to a given period of time. Once the concession is over, the local government must decide whether to renew it or return to in-house provision.

In the case of renewal, a new competitive tender could lead to the contract being awarded to either the incumbent or some other bidder, i.e., alternation. Literature on the determinants of contract renewal is, however, scarcer and mainly focuses on remunicipalization (Gradus and Budding 2018). Existing research suggests that the renewal of public service contracts largely depends on the type of service concerned, with the incumbent's contract more likely to be renewed for more complex services (Brown and Potoski 2003; Rodrigues, Tavares, and Araújo 2012) such as urban water services and waste disposal (Campos-Alba et al. 2017; Guérin-Schneider, Breuil, and Lupton 2014).

Competitive tenders in public services are seen as a means of introducing competition into sectors with natural monopoly conditions (Demsetz 1968); however, incumbents very often retain contracts. Although the debate is ongoing, some authors have construed the lack of alternation as a symptom of insufficiently effective competition and collusive behavior (Yvrande-Billon 2009). Lalive, Schmutzler, and Zulehner (2015) performed a comparative analysis of negotiations with the incumbent and open auctions in the procurement of railway services in Germany, finding that negotiations correlate with lower consumer surplus and higher prices. Conversely, renewal with the incumbent has also been perceived as the result of cooperation among the players (Beuve, Le Lannier, and Le Squeren 2018). In the case of the construction of social housing in France, Chever, Saussier, and Yvrande-Billon (2017) found that negotiations after an informal auction led to lower costs than those following open auctions. Kang and Miller (2015) developed a procurement auction model in which the degree of competition is optimally chosen by public buyers, finding that limiting competition does not necessarily result in higher procurement costs.

Little empirical evidence exists on the importance of incumbency in the contracting-out of public services, and the determinants of incumbent contract renewal. Guérin-Schneider et al. (2003, 50) noted that the incumbent’ renewal rate in urban water contracts in France during the period 1998–2001 was 87 percent; Amaral et al. (2009, 172) reported a rate of 88 percent in bus transport services in France, as an average for 1995–2002, and 63.5 percent in London between 1999 and 2006; and Yvrande-Billon (2009, 118) found an incumbent renewal rate of 83.8 percent in French bus transport in 1995–2006. To the authors’ knowledge, the latter study is the only one to examine the factors explaining why alternation is so rarely seen; the main finding is that large firm size is the most significant explanatory factor of incumbent renewal.

The advantage enjoyed by large firms in contract renewal can reinforce trends towards market concentration, particularly in public services with significant network costs, such as the urban water service. Increasing concentration in the water industry has been reported for all European countries with a major presence of private providers: France (Biswas and Tortajada 2014), Spain (González-Gómez, García-Rubio, and Guardiola 2012), England and Wales (Britton 2019), and the Czech Republic and all over Europe (Guinea and Erixon 2019). This is a relevant issue for public policy because weakened competition can compromise the potential benefits to be obtained from private participation in the water industry.

Against this background, this article studies the determinants of concession renewal for the private provision of urban water services in Spain. The research focuses on the factors explaining the probability of alternation, i.e., the incumbent being replaced by another bidder. The contribution to the field of research is twofold. On the one hand, this article provides the first empirical evidence on the factors explaining the result of public tenders for the renewal of concessions for the private provision of urban water services. On the other hand, going far beyond the existing literature, variables related to incumbent size, competition, transparency, neighboring municipalities, and municipalitiy size, in addition to several political issues, are considered as potential explanatory factors of the probability of alternation.

As a result of the wave of deregulation and privatization of public services that began in Anglo-Saxon countries in the late 1970s, some developed economies changed their laws to allow for private provision of urban water services (Ruíz-Villaverde, González-Gómez, and Picazo-Tadeo 2015). Nowadays, provision is entirely public—or, at most, with a token presence of private firms—in countries such as Austria, Denmark, Ireland, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden (EurEau 2018). Conversely, in England and Wales provision is fully in private hands, with the government's involvement limited to control and regulation. Lying between these two extremes are countries including the Czech Republic, France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and the United States, where legislation allows for public–private collaboration (Smith and Walker 2020). Furthermore, there has been intensive development of private provision in the Czech Republic, France, and Spain (EurEau 2018), where a trend towards increasing concentration in the hands of larger players in the water industry has also been reported.

In Spain, private firms currently provide urban water services to nearly 23 percent of municipalities and over 53 percent of the total population, according to the authors’ own estimates. Nevertheless, despite the deep-rooted tradition of private service delivery, some Spanish municipalities are returning to in-house provision, as happened in other European cities. Furthermore, unlike countries such as Italy or Switzerland where water firms also operate in other businesses, there are practically no multi-utility firms in Spain. Instead, more like in France, some Spanish water companies belong to large holdings that also deliver other local services, but through different subsidiaries. That said, many utilities in Spain jointly provide water distribution and wastewater treatment services.

Following this introduction, the background is presented and some hypotheses are established regarding contract renewal for urban water services. Then, the institutional context for the provision of urban water services in Spain is described, before detailing the data and the empirical strategy in the following section. After that, the results are presented and discussed. Finally, the main conclusions are summarized, and several policy implications and lines for further research are proposed.

Background and Hypotheses

Drawing on economic theory, a number of factors can be suggested as potential determinants of the outcome of contract renewal for the private provision of urban water services, and several hypotheses can be proposed. Firstly, although all bidders should compete on the same terms, incumbents likely enjoy a privileged position because of the knowledge they accumulated during the previous contract (Williamson 1976), such as in-depth information about the state of the distribution network and wastewater treatments plants (Chong, Saussier, and Silverman 2015). To ensure a level playing field, local governments should inform competing firms about the state of water infrastructures, which is not always easy given the difficulties in assessing some of their features (Chauchefoin and Sauvent 2014).

Looking beyond city councils’ responsibility to facilitate information to all bidders, larger firms might enjoy a number of competitive advantages in public tenders: they may benefit from economies of scale, have more resources and capabilities that they can deploy throughout the tender process, or have more experience in managing bids due to their larger presence in the industry. The competitive advantages held by larger players—incumbents or otherwise—work against small incumbents and are expected to reinforce the trend towards market concentration, as observed in some of the major European countries. Thus, the first hypothesis to be empirically tested is:

Hypothesis 1.Small incumbents are more likely to lose their contracts when they come up for renewal in competitive tenders.

Secondly, competition also matters. The number of bidders competing for the provision of the urban water service could influence the result of the tender, such that more competitors will likely boost the probability of alternation. Previous research suggests that competition affects key variables in public tenders. Coviello and Mariniello (2014) found that an increase in the number of bidders results in better economic proposals, thus reducing the costs of procurement. Bel, González-Gómez, and Picazo-Tadeo (2015) found that in areas with few providers and high market concentration, bidders anticipate weaker competition and thus propose higher water tariffs in public tenders. Thus, the second hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2.The more bidders admitted to the tender, the higher the probability of alternation.

Beyond factors related to the structure of the water industry, the transparency with which tenders are managed by public administrations could also substantially influence the outcome of the bidding. Greater transparency is expected to increase the number of competitors and to reduce the discretionary power of the local government to influence the result of the tender. Transparency can be seen as composed of different factors, most notably publicity and non-discretionary decisions. Coviello and Mariniello (2014) found that increased publicity has a positive effect on the number of bidders, which can make alternation more likely. Yvrande-Billon (2009) found that when the contract is awarded by means of a competitive tender—which could be seen as an indicator of transparency—the probability of renewal with the incumbent is lower than when the contract is hand-picked. Coviello, Guglielmo, and Spagnolo (2018) found that more discretion in the procurement process is positively related to the probability of incumbents winning the new contract, and that incumbent renewal can actually improve performance. 1 In Spain, a recent article by Albalate et al. (2017) confirmed that the passing of Law 30/2007 on Public Sector Contracts—which improved transparency in public procurement, regarding both publicity and non-discretionary decisions—substantially weakened the connections between political parties and big players in the water industry when it came to the contracting-out of urban water services. Hence, the third hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 3.Greater transparency in awarding public contracts increases the probability of alternation.

Furthermore, there is a series of political variables that might influence the result of tenders for the renewal of the contract for the private provision of urban water services. Local governments may have an interest in the incumbent retaining the contract at the time of the new tender, thus avoiding costs arising from the transfer of physical assets and human capital to a new firm (Laffont and Tirole 1993). While this interest would exist independently of the ruling political party, it seems reasonable to assume that it would be stronger when long-term relationships of trust and reciprocity have been established between local politicians and service providers (Brown, Potoski, and Van Slyke 2006); moreover, these relationships are expected to be closer when it is the ruling party at the time of the renewal that established them in a previous term in office. In this regard, Picazo-Tadeo, González-Gómez, and Suárez-Varela (2020) suggested that bonds of trust between providers of the urban water service and local politicians in Spain could explain relations of mutual dependence, such as the use of water tariffs for electoral purposes. Renewal with the incumbent would also require the local government to enjoy some discretionary power in the bidding process (Klein 1999), which might be more likely if it holds an absolute majority in the city council. Accordingly, the fourth hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 4.When the ruling political party in the city council at the time of the contract renewal was also in power in the prior term of office and holds an absolute majority, the probability of alternation decreases.

Municipality size could also affect the results of renewal tenders. Chong, Saussier, and Silverman (2015) suggested that more heavily populated cities are more attractive for bidders as they offer a larger market, although more clients could mean more management complexity, thus deterring some firms from participating in the tender. However, there are a number of other arguments supporting the idea that the probability of alternation might decrease in larger municipalities. On the one hand, according to González-Gómez, Picazo-Tadeo, and Guardiola (2011) it is more profitable to provide urban water services in more populated municipalities, so incumbents will strive to present competitive bids to preserve their contracts. On the other hand, the larger a municipality, the more a provider can exploit economies of scale (Bottasso and Conti 2009), and since the population tends to be more concentrated in large municipalities, economies of density can be exploited. Although high population concentration might also lead to congestion expenses, Bel, González-Gómez, and Picazo-Tadeo (2015) suggested the existence of economies of density in the provision of urban water services in Spain. Accordingly, the fifth hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 5.In larger municipalities there is a lower probability of alternation.

Furthermore, when the incumbent manages the urban water service in neighboring areas, fixed costs could be shared, which could constitute a competitive advantage that deters competitors from bidding. Moreton and Spiller (1998) found this effect in the US telecommunications sector. González-Gómez, Picazo-Tadeo, and Guardiola (2011) suggested that Spanish water firms that are already established in a given area would attempt to expand their business to take advantage of economies of scale, by offering attractive deals to neighboring municipalities. Experience in the management of water services in the local area can also reduce uncertainty in decision-making (Bel, González-Gómez, and Picazo-Tadeo 2015). Accordingly, a sixth and final hypothesis has been formulated as follows:

Hypothesis 6.When the incumbent also provides the urban water service in neighboring municipalities, the probability of alternation decreases.

The Institutional Context

The Management of Urban Water Services in Spain

The provision of urban water services in Spain is regulated by Law 7/1985 on Local Government Regulations, and Law 57/2003 on the Modernization of Local Government. The responsibility for the provision corresponds to local governments, which can decide whether the urban water service should be provided in-house or outsourced. With outsourcing, management can be either transferred to a government-owned firm or privatized. Furthermore, privatization can be carried out with either a fully private firm (contractual public–private partnership, PPP) or a public–private firm (institutional PPP).

In institutional PPPs, ownership is shared between the local government, which usually retains a large stake in the firm's capital to be able to define and control strategic objectives, and the private partner, which is in charge of running the day-to-day operations (Da Cruz and Marques 2012; Warner and Bel 2008). Furthermore, whatever the legal form of the urban water service provision, private ownership of networks is rarely seen in Spain mainly for historical reasons; accordingly, the infrastructure almost always remains under the ownership of local governments.

After the passing and entry into force of Law 7/1985, many local governments took the decision to privatize the management of the urban water service, to the extent that Spain is currently one of the developed countries with the largest presence of private firms in this sector (Bel 2020; EurEau 2018). As in other developed countries, the reasons behind the privatization of urban water services in Spain have been mostly pragmatic (González-Gómez, Picazo-Tadeo, and Guardiola 2011), financial (Miralles 2009), and to a lesser extent ideological and political (Picazo-Tadeo et al. 2012).

The private water industry in Spain is highly concentrated (Bel, González-Gómez, and Picazo-Tadeo 2013), with the market dominated by two major providers: Agbar (acronym of Aguas de Barcelona), which is part of the multinational group Suez and operates under different regional denominations; and Aqualia, which belongs to the Spanish group Fomento de Construcciones y Contratas (FCC). Albeit with a much smaller market share than these two big players, other firms with significant presence in the national market are Acciona and Gestagua. Furthermore, some firms originally provincial or regional in scope, such as Global Omnium and FACSA, have expanded their activity to other areas of Spain, thus increasing their market shares.

The Contracting-Out of Urban Water Services: Legal and Administrative Aspects

The contracting-out of urban water services in Spain is currently regulated by Law 30/2007 on Public Sector Contracts, which transposed to national legislation Directive 2004/18/EC of the European Council. According to this regulation, the bidding process unfolds as follows. The city council announces the public tender, including detailed information about the technical and economic conditions of the contract, the assessment criteria, and the commitments that must be met by the winning firm. Then, bidders place a first-price sealed bid that must also contain their technical and economic proposals, which might refer to issues such as service quality or emergency plans in case of service disruption. Finally, a jury adjudicates the public tender based on a set of criteria.

The mayor or any other city council member or public servant is the head of the jury, whose first undertaking is to verify that all the proposals meet the commitments required in the tender; non-complying bidders are given three days to amend rectifiable errors. Then, the jury assesses and scores the technical conditions offered by the admitted bidders, which necessarily requires some value judgments given the qualitative nature of some of these conditions. In a third step, the economic conditions offered by each bidder—which must include water tariffs and proposals for infrastructure investment, when appropriate—are also evaluated and scored. Following the joint assessment of both technical and economic conditions, bidders are awarded an overall score, on which the decision is based. Furthermore, when the assessment is based more on qualitative factors than on quantitative valuations, awarding reports need to be reassessed by an external committee formed by three referees; in practice, this requirement limits the discretionary power of the jury, making public tenders more transparent.

Finally, Law 30/2007 also requires public administrations, including city councils, to create a so-called contractor profiles website, in which all information regarding the contracting-out of public services and bidding processes must be announced. The purpose of this requirement is to introduce greater transparency into the management of public administrations.

Data, Variables, and Empirical Strategy

Data and Sources

The database built for this analysis contains data from 215 public tenders for the renewal of the contract for the provision of urban water services held in Spain between 2008 and 2019. All cases correspond to competitive tenders for contract renewal in which the service was formerly provided by a private firm, either a contractual or institutional PPP; in this literature, institutional PPPs are usually considered private managers as the day-to-day management is under the responsibility of the private partner. Accordingly, tenders in which urban water services were previously provided either in-house or by a public firm are excluded from the analysis; moreover, tenders in which water services return to in-house provision after having been managed by a PPP are also omitted (González-Gómez, Guardiola, and Ruíz-Villaverde 2009 and March et al. 2019 analyze the trend for remunicipalization of the urban water service in some Spanish cities).

Setting up the sample and building the dataset involved several steps. The starting point was the data in González-Gómez, García-Rubio, and González-Martínez (2014) on Spanish municipalities with private management of urban water services. The next step was to search the consultancy pages that publicize public tenders in Spain—including Infopublic and Infonalia—to identify tenders for contract renewal in the period of study. Having identified the relevant tenders for the purposes of this article, the information needed to carry out the empirical analysis was obtained from the city councils’ contractor profiles websites. In the few cases where this website was not available or it lacked some relevant data—most of them relating to tenders carried out at the beginning of the period analyzed—a direct request for information was sent to city council officials by email.

The time period for the empirical analysis—which runs from 2008 to 2019—is justified for two reasons. On the one hand, current legislation regulating the management of municipal services in Spain dates from 1985, with the enactment of Law 7/1985. This legislation allowed for the private provision of urban water services so that privatizations began to take place in the second half of the 1980s, and particularly in the 1990s, when many large and medium-sized Spanish municipalities opted for this form of management. Given that the term of the contract is generally about 20 years—although it can be up to 25 years—contract renewals did not begin to occur regularly until the second half of the 2000s. On the other hand, the passing of Law 30/2007 fueled greater transparency and public access to information concerning public contracts. As a result, the contractor profiles websites allowed full access to information on public tenders for the provision of urban water services occurring in Spain from late 2007. In particular, access was granted to a couple of essential variables for empirical purposes: the name of the firm awarded the contract, and the number and names of all bidders.

According to the data published on these websites, approximately 450 public tenders for the private provision of urban water services occurred in Spain between 2008 and 2019, of which about half were for the renewal of contracts. Although these figures must be taken with caution, since there are no official records and the information is highly decentralized, they suggest that the sample encompasses around 95 percent of the targeted population.

Variables

The central variable in the empirical analysis is the name of the firm awarded the contract for the provision of urban water services after the public tender. Based on this information the dummy variable Alternation is created, which is the dependent variable in the econometric models. It takes a value of 1 if the winner of the tender is different from the incumbent provider, and 0 if the contract is awarded to the incumbent. Alternation occurs in 35.3 percent of cases in the sample, while incumbent renewal is the outcome in the remaining 64.7 percent.

The six hypotheses posed in this research are tested by means of specific sets of covariates. According to H1, a higher probability of alternation is expected if the incumbent is a small firm. This is empirically tested by including the dummy variable Small incumbent, which takes a value of 1 if the incumbent is a firm other than Aqualia or Agbar, the two largest firms in the private water industry in Spain, and 0 if the incumbent is one of the two abovementioned firms. 2 By introducing the incumbent size as a dummy variable, the possible non-linearity of its effect on the probability of alternation can be considered. Furthermore, the robustness of the results for hypothesis H1 has been checked by relaxing the non-linear assumption and replacing the dummy Small incumbent by the continuous variable Market share, which measures the incumbent's share of the national market in terms of population served in the year prior to the tender, to avoid endogeneity issues.

Hypothesis H2 claims that more competition in the public tender reduces the probability of the incumbent's successful contract renewal. The degree of competition is measured by the variable Number of bidders, which represents the number of effective bidders competing for the contract.

Furthermore, H3 states that higher transparency standards in contracting procedures increases the probability of alternation. This claim is empirically tested with the variable Provincial transparency provided by the non-governmental organization International Transparency, which is a dummy that takes a value of 1 if there is complete transparency in contracting procedures measured at the provincial level. 3 This indicator is built with the information provided in the provincial councils' websites regarding four items. The first two refer to the procedure for contracting services: composition and convening of the juries in charge of adjudicating the tenders, and full minutes of the sessions of the jury. The other two items refer to the relationship between the provincial council and suppliers and contractors: list and amount of transactions with suppliers, and list and value of all contracts awarded and successful bidders. Complete transparency is considered to exist when information regarding the four abovementioned items is published in its entirety on the provincial council's website.

Hypothesis H4 is related to political issues, and suggests that the probability of alternation decreases when the ruling political party in the city council at the time of the renewal decision was also in power in the prior term of office, and holds an absolute majority. This hypothesis is tested through the dummy variable Continuity and majority, which takes a value of 1 when the abovementioned situation occurs. Additionally, two further political variables are included to capture the common effects generated by the two main political parties in Spain: the dummies PSOE (center-left-wing Partido Socialista Obrero Español) and PP (right-wing Partido Popular), which take a value of 1 when the awarding local government is ruled by one of these two parties, respectively. In this case, there is no clear expectation—positive or negative—regarding the effect of these variables on the probability of alternation.

The two final hypotheses are H5 and H6. On the one hand, H5 refers to the effect of municipality size on the probability of alternation. The hypothesis is tested through the variable Population, measured by the number of inhabitants in thousands, for which a negative sign is expected. On the other hand, the neighboring effect suggested by H6 is tested through the variable Vicinity, which measures the incumbent's share of the regional market in the year prior to the tender, in terms of the number of municipalities served. According to Albalate et al. (2017), regional markets are the relevant ones regarding private provision of urban water services in Spain. A negative sign is expected as the probability of alternation should decrease if the incumbent holds a dominant position in the region.

In addition to the abovementioned variables aimed at testing the research hypotheses, two further controls have been included in the empirical models: the Percentage of tenders, capturing the number of tenders in which the operator has participated over total tenders held in the region in the period analyzed; and the Year in which the tender for contract renewal took place. While the former is aimed at controlling for the experience and knowledge of the incumbent in tenders held in the region, the latter is intended to capture any common trends in the likelihood of alternation due to other unobserved factors not included in the set of determinants that might vary over time.

Table 1 describes all these variables and their sources in more detail, while table 2 displays some descriptive statistics.

| Description | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | ||

| Alternation | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the incumbent is not awarded the renewed contract, i.e., there is a change in the provider of the urban water service (alternation); and 0 otherwise. | City councils |

| Covariates | ||

| Small incumbent | Dummy variable equal to 1 if a firm other than Aqualia or Agbar—the two largest players in the private water industry in Spain—was the incumbent before the competitive tender for contract renewal; and 0 otherwise. | City councils |

| Market share | Incumbent's share of the national market for private urban water provision in the year prior to the renewal, in terms of population served. | City councils |

| Number of bidders | Number of bidders competing for the renewal of the contract for the urban water service provision. | City councils |

| Provincial transparency | Indicator of transparency in public sector contracts calculated at the provincial level. Dummy variable equal to 1 in cases of complete transparency; and 0 otherwise. | Transparency International and own elaboration |

| Continuity and majority | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the ruling party in the city council at the time of contract renewal was also in power in the prior legislature, and holds more than half the city council seats; and 0 otherwise. | Ministry of Territorial Policy and Public Service; and Home Office |

| PSOE | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the center-left-wing Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) was in power at the time of contract renewal; and 0 otherwise. | Home Office |

| PP | Dummy variable equal to 1 if the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) was in power at the time of contract renewal; and 0 otherwise. | Home Office |

| Population | Number of inhabitants (in thousands). | National Institute of Statistics |

| Vicinity | Incumbent's share of the regional market for private provision of the urban water service, computed in terms of municipalities served in the year prior to the contract renewal. | City councils |

| Participation in tenders | Share of total tenders held in the region in which the incumbent has participated during the whole period 2008–2019. | City councils |

| Year | Year in which the contract for the provision of the urban water service was renewed. | Own elaboration |

| Covariates | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small incumbent | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Market share | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.00003 | 0.507 |

| Number of bidders | 2.55 | 1.68 | 1 | 10 |

| Provincial transparency | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0 | 1 |

| Continuity and majority | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| PSOE | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0 | 1 |

| PP | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Population (000 s) | 12.40 | 25.68 | 0.097 | 211.9 |

| Vicinity | 0.32 | 0.25 | 0.001 | 0.94 |

| Participation in tenders | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.021 | 1 |

| Year | 2013.47 | 3.12 | 2008 | 2019 |

Empirical Strategy

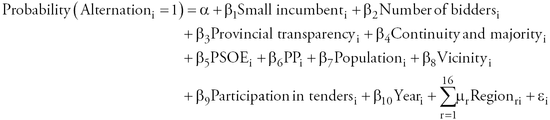

(1)

(1)Equation (1) includes all the variables needed to test the hypotheses posed in this article, in addition to control variables and a set of regional dummies—denoted by Region—to identify the regions in which tenders take place—all 17 Spanish regions except Navarre, for which there are no observations. These regional dummies control for region-specific common characteristics of municipalities and markets. In some models, the common time trend is replaced by specific dummies for the years in which tenders take place, to account for the specific individual effects produced by any particular year that might be affecting the behavior of both municipalities and firms. Moreover, errors are clustered at province level to account for possible correlation within the same geographical area, explained by shared practices and other common characteristics. The estimations have been carried out with Stata software; a specification test—the linktest—has also been run, the results of which confirm that all models are correctly specified.

Results

The empirical results are presented in table 3. The baseline estimates are in models (1) and (2); the former includes all variables specified in equation (1), while in the latter the time trend Year is replaced by year-specific dummy variables. Furthermore, in models (3) and (4) the dummy Small incumbent is replaced by the continuous variable Market share, to check whether relaxing the non-linear assumption about the relationship between incumbent size and the probability of alternation affects the results regarding hypothesis H1. The last column displays the marginal effects evaluated at mean values for the baseline model (2).

| Covariates | Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Marginal effects from model (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Incumbent size | |||||

| Small incumbent | 0.8161 (0.5764) | 0.9154 (0.5737) | — | — | |

| Market share | — | — | −1.8222 (1.4461) | −1.7165 (1.4113) | |

| H2: Competition | |||||

| Number of bidders | 0.5150*** (0.1166) | 0.5424*** (0.1323) | 0.5201*** (0.1180) | 0.5386*** (0.1347) | 0.11*** |

| H3: Transparency | |||||

| Provincial transparency | 0.9588*** (0.3144) | 1.0769*** (0.3380) | 0.9947*** (0.3061) | 1.0758*** (0.3384) | 0.22*** |

| H4: Politics | |||||

| Continuity and majority | −1.4306*** (0.2903) | −1.4445*** (0.3432) | −1.4665*** (0.3319) | −1.4679*** (0.3778) | −0.30*** |

| PSOE | −0.1963 (0.7644) | −0.2179 (0.7623) | −0.1950 (0.7828) | −0.2563 (0.7849) | |

| PP | 0.3971 (0.7350) | 0.5915 (0.7829) | 0.3918 (0.7569) | 0.5487 (0.8023) | |

| H5: Municipality size | |||||

| Population (000 s) | −0.0416* (0.0220) | −0.0394* (0.0241) | −0.0443** (0.0221) | −0.0433* (0.0245) | −0.01* |

| H6: Neighboring | |||||

| Vicinity | 2.1850 (1.9059) | 2.1570 (1.7372) | 1.8692 (1.5680) | 1.7296 (1.4124) | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Participation in tenders | −1.5071 (1.4880) | −1.0649 (1.4153) | −1.2053 (1.6158) | −0.8548 (1.5152) | |

| Year | −0.0656 (0.0626) | — | −0.0694 (0.0637) | — | |

| Region dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year dummies | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Number of observations | 213 | 213 | 213 | 213 | 213 |

| Log likelihood | −106.71 | −103.68 | −106.81 | −104.18 | — |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.24 | — |

- Statistical significance at ***1%, **5%, and *10% level. Clustered standard errors in parentheses. Two observations (out of 215) are left out due to perfect collinearity (models predict success perfectly).

The results are fairly stable and consistent across models. Hypothesis H1 is rejected since the coefficient associated with Small incumbent lacks statistical significance in models (1) and (2); hence, no support is found for the hypothesis that alternation is more likely when the incumbent is a small player. This finding is further checked in models (3) and (4), with the results confirming that incumbent size is not a relevant determinant of alternation in contract renewal for the private provision of urban water services in Spain. Accordingly, the lack of support for H1 does not depend on the non-linearity assumption considered in the baseline models.

The positive sign of the estimated parameter for the Number of bidders and its high statistical significance—at 1 percent across all models—indicates that the more firms bidding in the tender, the higher the probability of alternation. 5 Therefore, the results confirm H2, which stresses the importance of competition intensity in the result of the tender. The estimated coefficient associated with the variable Provincial transparency is statistically significant at the 1 percent in all models, suggesting that the probability of alternation goes up as transparency improves. This finding confirms H3, which states that higher transparency standards undermine the incumbent advantage.

There is also empirical support for H4, which addresses the discretionary power of well-established political parties which ran the city council in the previous term of office, and which hold an absolute majority when the renewal is awarded. The estimated sign for the variable Continuity and majority is negative and statistically significant at the 1 percent in all four models, confirming that these governments are more likely to renew the contract with the incumbent. The different political parties—PP or PSOE—do not seem to be associated with particular contracting patterns.

Hypothesis H5 regarding the effect of municipality size on the probability of alternation is also backed by the empirical results, although with lower precision. The coefficient for the variable Population is negative and statistically significant at the 5 percent in model (3), and just at 10 percent in models (1), (2), and (4). These empirical findings suggest that larger municipalities are more likely to renew the contract with the incumbent.

In contrast, hypothesis H6 on neighboring effects is not supported by the empirical results. The estimated coefficient for Vicinity—which accounts for the presence of the incumbent in the region in terms of municipalities served—is not statistically significant in any of the models. This suggests that having a larger share of the regional market for the private provision of urban water services does not provide incumbents with any advantage regarding the probability of renewing the contract. The neighboring effect has been further tested with the incumbent's share of the regional market computed in terms of the population served instead of municipalities. However, no significant effect is found either.

Finally, no statistically significant effects were found for either of the two control covariates included in the estimations: Participation in tenders, accounting for incumbents' experience and knowledge of the regional market; and the common time trend, represented by Year.

Discussion

The findings described above seem to support four of the hypotheses posed in this research, regarding competition (H2), transparency (H3), politics (H4), and municipality size (H5). Conversely, robust statistical support is not found for the remaining two hypotheses about the incumbent's size (H1) and the neighboring effect (H6).

The empirical results regarding H1—which indicate that incumbent size does not seem to matter for the outcome of public tenders for the renewal of urban water service provision—merit further discussion. This finding runs counter to prior expectations based on the existing literature (Yvrande-Billon 2009), as competitive advantages held by larger players—incumbents or otherwise—have frequently worked against small incumbents, thus reinforcing trends towards market concentration in some of the major European countries. To gain a better insight into the dynamics of concentration in the Spanish market for the private provision of urban water services, two different strategies are applied.

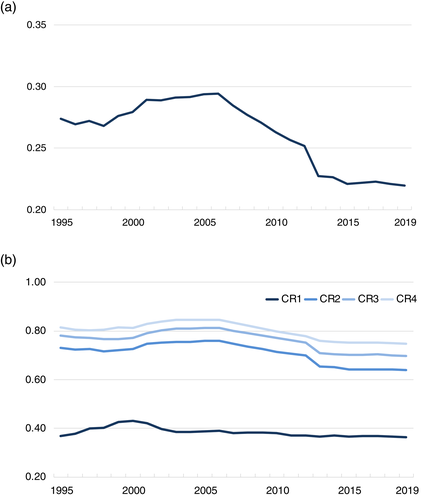

First, several concentration indices for the period 1995–2019 are calculated, comprising two symmetric 12-year subperiods before and after the legal reform of procurement passed in Spain in 2007 (Law 30/2007 on Public Sector Contracts). That reform, together with the parallel reform of the legal framework for donations to political parties (Law 8/2007 on the Financing of Political Parties) reduced politically driven favoritism in the adjudication of water contracts in Spain (Albalate et al. 2017). Merging the information provided in Albalate et al. (2017) on Spanish municipalities with private delivery of urban water services and the database specifically produced for this article, a greatly enlarged database of municipalities is compiled, which includes up to 988 municipalities (in 2019) with a private provider of urban water services for which the name is known; this sample covers over 50 percent of the private water market in Spain in terms of municipalities, and 70 percent in terms of population. Then, the Hirschman–Herfindahl index (HHI) of market concentration, and the concentration ratios CR1, CR2, CR3, and CR4 are computed.

Figure 1 shows that market concentration in the Spanish private water industry has not increased in the period analyzed. The HHI trend in figure 1a confirms that concentration increased until 2006, when it reached a maximum (0.295); since then, the HHI has continuously declined, reaching a minimum in 2019 (0.220). Likewise, figure 1b shows that the market share of the largest firm (CR1) decreased in the early 2000s due, apparently, to other large firms entering the market, as suggested by the growth of the ratios CR2, CR3, and CR4. As in the case of the HHI, all CRs register a continuous decline after 2006, thus confirming the trend towards less concentration after the legal reforms on procurement and political parties’ funding passed in 2007—which, as mentioned, substantially weakened the effects of political connections and favoritism in the awarding of water contracts (Albalate et al. 2017).

Indicators of Concentration in the Spanish Private Water Market, 1995–2019 a. Hirschman–Herfindahl Index (HHI). b. Concentration Ratios (CR).

Source: Own elaboration.

Note: The HHI has been computed as the sum of the squares of market shares of all firms operating in the private water industry. CR1 represents the market share of the leading firm, while CR2, CR3, and CR4 represent the market share of the second, third, and fourth leading firms, respectively. Market shares have been computed based on the number of municipalities supplied by private firms.

As a second strategy to further understand results regarding market concentration, a logistic regression is run on a restricted sample that only includes tenders resulting in alternation (76 tenders). The dependent variable is a dummy equal to 1 if the contract is awarded to a large firm—either Agbar or Aqualia—and 0 otherwise; the covariates and controls are the same as in model (2) of table 3, except the region dummies. A market trend towards greater concentration—without significant mergers—should be reflected in a positive relationship between the variable Small incumbent and the probability of awarding the contract to a large firm. The results are presented in table 4. The lack of statistical significance of the coefficient associated with Small incumbent suggests that large firms are not gaining market share by replacing small incumbents in public tenders.

| Covariates | Model (5) |

|---|---|

| Small incumbent | −1.7831 (1.4441) |

| Rest of covariates | Yes |

| Clusters by province | Yes |

| Region dummies | No |

| Year dummies | Yes |

| Number of observations | 75 |

| Log likelihood | −25.51 |

| Wald chi2 | 156.95*** |

| Pseudo R2 | .48 |

- ***Statistical significance at 1%. One observation (out of 76) is left out because a year-specific binary variable predicts failure perfectly. Regional dummies are not included in the estimations because 12 of them (out of 16) have to be omitted due to perfect collinearity.

An additional robust finding from the empirical analysis is that competition and transparency both boost alternation. Accordingly, an increase in the number of bidders in public tenders and greater transparency seems to work in this direction, reducing the likelihood of incumbents’ successfully bidding for contract renewal. This finding is consistent with those reported by Coviello and Mariniello (2014) and Albalate et al. (2017). Conversely, long-standing relationships between incumbents and political parties, along with the discretionary power that comes from holding an absolute majority, reduce the probability of alternation—consistent with Picazo-Tadeo, González-Gómez, and Suárez-Varela (2020)—as does the fact of being a large municipality. But which of these effects has the greatest impact on the likelihood of alternation? The marginal effects shown in the last column of table 3 suggest that the politics of contracting-out and the accountability and public checks on political parties—via transparency requirements—play a major role in the outcome of public tenders for the renewal of water utility contracts in Spain.

Summing up, there is an ongoing scholarly debate on how best to serve the interests of citizens regarding the provision of local public services. In the urban water industry, one controversy concerns the opportunity for private provision: some countries allow privatization, raising the question of whether local governments should directly negotiate contracts with service providers or award them through competitive bidding processes. If they opt for public tenders, ensuring a level playing field and guaranteeing competition are of critical importance. In principle, alternating or renewing with the incumbent is neither good nor bad in itself; what really matters is that it is the result of effective competition. A major finding of this article is that there is no evidence that the big players in the Spanish private market for urban water services compete at an advantage; smaller firms are competing on an equal footing as they have benefited from the 2007 regulatory changes aimed at making public tenders more transparent and competitive. Besides, transparency appears to be a powerful instrument for boosting competition, even in oligopolistic industries with dominant players such as the water industry.

Conclusion, Policy Implications, and Further Research

Contract renewal with the incumbent is a very common outcome of public tenders, which can be seen as a potential indicator of lack of competition in public services (Guérin-Schneider, Bonnet, and Breuil 2003; Yvrande-Billon 2009). There is scarce up-to-date information and empirical research on this issue in the literature. This article contributes to the field by analyzing the main factors driving the probability of alternation in contracts awarded for the private provision of urban water services. The analysis is carried out using a large sample of bidding processes taking place in the Spanish urban water sector between the years 2008 and 2019.

According to the empirical findings, small firms do not seem to be at a disadvantage as incumbents, given that the likelihood of alternation is not associated with the size of the incumbent. Furthermore, this result is consistent with the finding that market concentration in the private segment of the Spanish urban water market, which was on the rise in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century, has instead undergone a decline in the period for which the empirical analysis is conducted.

More competitors bidding for the contract may undermine the incumbents’ advantage and facilitate the alternation of service providers in the Spanish private water industry. Thus, policy measures aimed at encouraging water firms to bid for public tenders could be put in place, particularly in small municipalities, to foster competition. Such measures could include reducing bureaucracy and simplifying the administrative requirements for access to public tenders. Contracting-out practices require integrity and transparency in their procedures to ensure that the public interest is served. The empirical results give some interesting support to the notion that transparency is an effective tool for diminishing the advantage of incumbents. On the contrary, this research suggests that some political factors may work in favor of incumbents: entrenched governments ruling with an absolute majority in the city council are more likely to renew contracts with incumbents.

This article is not without its limitations, which may pave the way for future investigation. The empirical analysis is focused on the Spanish private market of urban water services, so future research in other countries and markets may help to ascertain whether these results can be generalized. Furthermore, the results should be interpreted with caution, avoiding causal inferences regarding the associations found in the statistical analysis, as the article does not provide a quasi-experimental setting. Future studies would greatly benefit from identifying external shocks or being able to build an appropriate framework to perform quasi-experiments.

In short, even if there are some gaps in the information needed to provide full, consistent answers to all the questions posed in this article, the findings obtained enable progress towards developing an understanding of the alternation of urban water service providers as the result of public tenders for contract renewal. These results open the door to fruitful and interesting future research on the topic.

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize the insightful comments from three anonymous referees. They also acknowledge the financial support received from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) (projects ECO2016-75237-R, ECO2017-86822-R, and PID2019-104319RB-I00), the Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEO 2018-102), the Generalitat de Catalunya (project SGR2017-644), the Government of Andalusia and the ERDF (projects P18-RT-576 and B-SEJ-018-UGR18), and the University of Granada (Plan Propio. Unidad Científica de Excelencia: Desigualdad, Derechos Humanos y Sostenibilidad-DEHUSO). The usual disclaimer applies.

Notes

Biographies

Daniel Albalate is associate professor of Economics and Public Policy at Universitat de Barcelona and Deputy Director of the Observatory of Analysis and Evaluation of Public Policies at UB (OAP-UB). His research focuses on the analysis and evaluation of public policies, local public services reforms, and the economics of transportation and infrastructure. On these topics he has published more than 50 refereed articles. For more details see http://www.danielalbalate.cat

E-mail: [email protected]

Germà Bel is professor of Economics and Public Policy at Universitat de Barcelona, Director of the Pasqual Maragall Chair on Economics and Territory, and Director of the Observatory of Analysis and Evaluation of Public Policies at UB (OAP-UB). His research focuses on government reform, local public services, transportation, and infrastructure. On these topics he has published several books and more than 100 peer-refereed articles. He is Editor of Local Government Studies. For more details, visit www.ub.edu/oap/germa-bel/

E-mail: [email protected]

Francisco González-Gómez is professor of Applied Economics at Universidad de Granada and a senior researcher at the Water Institute of the same university. His research focuses on urban water management, including economic, political, and environmental issues. He is a member of the Editorial Board of the International Journal of Water Resources Development.

E-mail: [email protected]

Andrés J Picazo-Tadeo is professor of Economics at University of Valencia. His main areas of research are environmental economics, water economics and efficiency, and productivity analysis. He is Editor-in-Chief of Applied Economic Analysis.

E-mail: [email protected]