Factors associated with reduced sleep among spouses and caregivers of older adults with varying levels of cognitive decline

Disclosure: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

Background

Caregivers of persons with cognitive decline (PWCD) are at increased risk of poor sleep quantity and quality. It is unclear whether this is due to factors in the caregiver versus in the PWCD.

Methods

This secondary data analysis using Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study data from the Health Retirement Study examined factors contributing to reduced sleep/rest among spouses and caregivers of older adults with varying levels of cognitive decline (cognitively normal (CN), cognitive impairment but not dementia (CIND), or dementia).

Results

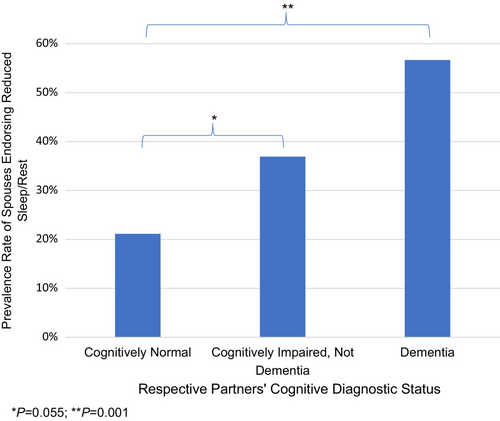

In our preliminary analysis, among N = 218 spouses (not necessarily caregivers) (mean age (SD) = 73.77 (7.30); 70.64% female) of older adults with varying levels of cognitive decline, regression revealed that frequency of sleep complaints was lowest among spouses with CN partners, second highest with CIND partners, and highest with dementia-partners, X2 = 26.810, P = 0.002. Primary aim: among n = 136 caregivers of PWCD (mean age (SD) = 59.27 (13.97); 74.26% female; 22.79% spouses), we analyzed whether caregiver reduced sleep/rest was predicted by PWCD factors (i.e., frequent nighttime waking, dementia severity) and/or caregiver factors (i.e., depression symptoms, caregiver role overload). Regression revealed that caregiver depression symptoms (d = 0.62) and role overload (d = 0.88), but not PWCD factors, were associated with reduced caregiver sleep/rest after adjusting for demographic factors, caregiving frequency, and shared-dwelling status (overall model: X2 = 31.876, P = 0.002). Exploratory analyses revealed that a caregiver was 7.901 times more likely (95% CI: 0.99–63.15) to endorse experiencing reduced sleep/rest if back-up care was not available (P = 0.023).

Conclusion

Findings highlight that the frequency of reported sleep problems among spouses increases in a stepwise fashion when partners have dementia versus CIND versus CN. The results also emphasise that caregiver mental health and burden are strongly associated with caregiver sleep disturbances and thus may be targets of intervention for caregiver sleep problems.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 11 million adults in the United States (U.S.) serve as unpaid, informal caregivers for adults with dementia (i.e., cognitive decline that hinders daily functioning).1 As Baby Boomers continue to age, there will be an increased prevalence of ageing persons with cognitive decline (PWCD) who require support from informal caregivers, as our current social and healthcare systems cannot meet the needs of patients with dementia through formal means.2 Caregivers of PWCD are at increased risk of subjective cognitive decline,3 dementia,4 depression,5 anxiety,5 and adverse physical health outcomes.6, 7 Cognitive, physical, and mental health outcomes in general have been associated with various aspects of sleep quantity and quality in large, population-based studies.8, 9 In particular, insomnia (i.e., persistent difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep that interferes with daily functioning) and excessively short sleep duration (i.e., <5 h sleep/night) are associated with mental health disorders, physical health conditions,10 and risk of cognitive decline.11-14 Moreover, a growing body of literature demonstrates that caregivers of adults with dementia are at elevated risk of sleep disturbances compared to both non-caregivers15 and caregivers of individuals without dementia.16 For example, a meta-analysis of 3268 caregivers of individuals with dementia revealed that relative to age-matched non-caregivers, caregivers had lower sleep durations (2.42–3.50 fewer hours of sleep per week) and poorer sleep quality.15 Given that caregivers of PWCD are at risk of adverse mental health, physical health, and cognitive changes and that sleep appears to play an important role in these outcomes, it is important to understand more about sleep disturbances among caregivers of older adults with cognitive impairment.

Spouses and spousal caregivers of PWCD may be particularly vulnerable to sleep problems as they are likely to bed-share, room-share, and/or live in the same home as the PWCD and may have sleep disrupted by nocturnal events and behaviours of the PWCD.17 Although sleep disturbances among spousal caregivers of adults with dementia have been well documented, there is a paucity of research investigating sleep among spouses and caregivers of older adults who have cognitive impairment but not dementia (CIND, often referred to diagnostically as mild cognitive impairment, MCI). CIND individuals have cognitive decline but can maintain functionality in activities of daily living with compensatory strategies or light modifications.18 While caregivers and spouses of CIND older adults may not be required to provide as much support as caregivers of those with dementia,19 there is evidence that providing informal support for CIND older adults is still associated with significant time burden and psychological distress.19, 20 Additionally, there appears to be a stepwise increase in psychological distress when caring for someone with dementia versus CIND.21 Given the close relationship between sleep and mental health, caregivers of persons with dementia may be at greater risk of poorer sleep quantity/quality relative to caregivers of CIND individuals.

There is also a lack of research examining specific predictors of sleep disturbances among caregivers of PWCD, with the majority of existing studies taking place outside of the U.S.22-24 A small body of literature has demonstrated that caregiver depression and anxiety symptoms,22-25 level of caregiver burden/role overload,23, 25, 26 and disturbed sleep in the PWCD24 are associated with reduced sleep quality and/or quantity among caregivers of PWCD. To our knowledge, there have not been U.S.-based studies that directly examine the extent to which PWCD factors, such as dementia severity and nighttime sleep disturbances, versus caregiver factors, such as depression and caregiver role overload, influence the presence of sleep disturbances among caregivers of PWCD. Further, the potential roles of protective factors that may buffer the relationship between caregiving status and adverse sleep outcomes, such as perceived rewarding aspects of caregiving and the availability of back-up care for the PWCD, have also not been thoroughly investigated, although evidence suggests that positive affect in caregivers may be associated with improved sleep.27

The primary purpose of this study was to investigate factors influencing sleep complaints among spouses and caregivers of community-dwelling PWCD in the U.S. who were diagnosed with cognitive impairment using rigorous diagnostic criteria, by answering the following questions.

Preliminary analysis

Does frequency of sleep disturbance among spouses depend on whether their partner is classified as cognitively normal (CN), CIND, or dementia? We hypothesise that frequency of spousal reduced sleep/rest complaints will differ significantly by diagnostic status (CN vs. CIND vs. dementia), with lowest frequencies observed among spouses of CN individuals and highest frequencies among spouses of persons with dementia.

Primary aim

Among caregivers of adults with CIND or dementia, are PWCD factors (i.e., frequent nighttime waking; dementia severity rating) and/or caregiver factors (i.e., depression symptoms and caregiver role overload) associated with the presence of reduced sleep/rest for caregivers? Based on evidence reviewed above, we hypothesise that (Hypothesis 1) all PWCD and caregiver factors will be associated with reduced sleep among caregivers. In a separate exploratory analysis, we investigated whether (Exploratory Hypothesis 2) increased perceived rewards/benefits of caregiving and the availability of back-up care would be associated with reduced sleep/rest complaints among caregivers of PWCD.

METHODS

Data source

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from the authors' institution to conduct this secondary data analysis. Data for the present study originated from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS), a supplement to the Health Retirement Study (HRS, grant number NIA U01AG009740; conducted by the University of Michigan) that conducted a U.S. population-based study of dementia. Baseline ADAMS data (referred to as ‘Wave A’ in the ADAMS study) were collected between August 2001 and December 2003 via in-home assessments (see Langa et al. and Heeringa et al. for study information, design, and methodology).28, 29 ADAMS participants whose primary language was English or Spanish were included in the study.

As detailed in our recent paper examining patterns of sleep disturbances across stages of cognitive decline,30 ADAMS participants were a subset of the 1770 HRS respondents aged ≥70 from the 2000 and 2002 waves of HRS data collection. Sampling strategy for ADAMS participants included ensuring there were sufficient participants from each cognitive stratum, ranging from ‘low functioning’ to ‘high normal’ (which was determined by a self- or proxy-cognitive assessment measure in the parent HRS study), and oversampling Hispanic and Black participants to achieve a nationally representative racial/ethnic sample of older adults.31 ADAMS participants completed a 3–4-h structured evaluation, which included a battery of 13 neuropsychological tests and self- and informant-report measures. Evaluations were conducted by a nurse and a neuropsychology technician. Study participants' cognitive diagnostic status (referred to henceforth as ‘diagnostic status’) was determined by a multidisciplinary team, including a geropsychiatrist, neurologist, neuropsychologist, and cognitive neuroscientist, who reviewed the results from the evaluation interview, questionnaires, and neuropsychological tests. When available and necessary for diagnostic consensus, the team also reviewed participant medical records. Individuals were considered CN if they had no functional impairment and neuropsychological test scores within the normal range (i.e., no scores fell below 1.5 standard deviations of the mean). Individuals were considered CIND if the individual or the informant present at the visit reported subjective cognitive or functional impairment that did not meet criteria for dementia (per Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-III-R and DSM-IV definitions) or performance on neuropsychological measures was below expectation (with at least one score ≥1.5 standard deviations below published norms).32 According to the study authors, CIND is similar to MCI except that MCI requires both objective cognitive impairment on testing AND self- and/or informant-reported subjective complaints regarding cognition and/or function.32 Individuals were assigned to the dementia group based on DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria.33, 34

As part of the ADAMS evaluations, a knowledgeable informant completed questionnaires about the participant and themselves. Regardless of participant diagnostic status, all informants (including those of CN participants) were asked to complete an informant questionnaire developed for the ADAMS, which included questions about caregiving.28, 29 There was a 96.03% informant questionnaire completion rate among spousal cohabitating informants (regardless of participant diagnostic status) and an 84.52% informant questionnaire completion rate among informants identified post-hoc as primary caregivers of participants with CIND or dementia.

Current study sample

Spouses of older adults with varying levels of cognitive decline (preliminary analysis)

To evaluate the extent to which reduced sleep/rest among spousal informants varied by their partners' cognitive diagnostic status, we analyzed data from all informants who were spouses of ADAMS participants in CN, CIND, or dementia groups. Only spouses who lived with the participant were included to reduce the potential influence of marital status and/or living situation on the relationship between cognitive diagnostic status and partner sleep disturbances. Unfortunately, no information on bed- or room-sharing was available in this dataset. This analysis allowed spouses of the CN older adults to serve as a comparison group for spouses of those with a cognitive diagnosis, thus enabling us to investigate how being closely associated with an older adult with cognitive decline may affect sleep. Of the 856 participants originally in ADAMS, there were n = 218 spousal informants who lived with the participant and who completed the informant questionnaire (see Table 1).

| Age, mean (SD) | 73.77 (7.30) |

| Gender, % female | 70.64% |

| Education | |

| <12 years | 22.02% |

| 12 years | 34.40% |

| >12 years | 43.58% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 81.19% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.01% |

| Hispanic | 5.96% |

| Associated partner characteristics | |

| Age | 77.44 (4.99) |

| Gender, % female | 29.36% |

| Education | |

| <12 years | 38.07% |

| 12 years | 29.82% |

| >12 years | 32.11% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 82.57% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 11.47% |

| Hispanic | 5.96% |

| Partners' cognitive diagnostic status | |

| Cognitively normal | 56.42% |

| Cognitive impairment, not dementia | 29.82% |

| Dementia | 13.76% |

| Possible/probable AD | n = 21 |

| Possible/probable VaD | n = 5 |

| Other dementia | n = 4 |

- Data represents % of sample, unless otherwise noted.

- AD, Alzheimer's disease; PWCD, person with cognitive decline; VaD, vascular dementia.

Caregivers of people with cognitive decline (primary aim)

- A) ‘In the past month, have you provided care to your friend or relative by actively helping with any of [these] tasks [getting across a room, dressing, bathing, eating, getting out of bed, using the toilet, preparing a meal, shopping for groceries, making telephone calls, taking medication, or managing money] or by supervising him/her to ensure safety, provide reassurance, or to make sure that nothing goes wrong?’

- B) ‘Are you the person most responsible for the care of your friend or relative?’

Participants who endorsed both A and B (n = 179) will be referred to going forward as caregivers (‘CG’). After list-wise deletion eliminated cases with one or more missing variables for the primary aim, a final sample of n = 136 CG (see Table 2) was used to test Hypothesis 1 and a final sample of n = 131 CG was used to test Hypothesis 2. Please see Appendix S1 for further detail on missing data.

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.27 (13.97) |

| Gender, % female | 74.26% |

| Education | |

| <12 years | 19.85% |

| 12 years | 32.35% |

| >12 years | 47.79% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 68.66% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22.39% |

| Hispanic | 8.96% |

| Relationship to PWCD | |

| Spouse | 22.79% |

| Child or child-in-law | 54.41% |

| Other family member | 16.18% |

| Non-family | 6.62% |

| Lives with PWCD | 64.71% |

| Years known PWCD | 47.98 (16.03) |

| Days helped PWCD in last month | 21.80 (11.83) |

| Associated PWCD characteristics | |

| Age | 84.66 (7.48) |

| Gender, % female | 60.29% |

| Education | |

| <12 years | 61.03% |

| 12 years | 23.53% |

| >12 years | 15.44% |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 69.85% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21.32% |

| Hispanic | 8.82% |

| PWCD diagnostic status | |

| Cognitive impairment, not dementia | 34.56% |

| Dementia | 65.44% |

| Possible/probable AD | n = 66 |

| Possible/probable VaD | n = 18 |

| Other dementia | n = 5 |

- Data represents % of sample, unless otherwise noted. Among associated PWCD, average Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score was 0.5 (SD = 0.2) for CIND and 1.6 (SD = 1.0) for dementia.

- AD, Alzheimer's disease; PWCD, person with cognitive decline; VaD, vascular dementia.

Measures and selection of variables

The majority of variables below were abstracted from the informant questionnaire, which was developed for the ADAMS unless otherwise noted.19 This manuscript's methodology was informed by methodology used by Fisher and colleagues (2011), who used the ADAMS data to examine characteristics and outcomes of caregivers of adults with dementia versus CIND but did not focus on sleep.19 The following information was abstracted from the informant questionnaire: informant age, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, relationship to the participant (e.g., spouse), whether the informant lived with the participant, and the number of days the informant helped the participant in the last month (see Tables 1 and 2). See Appendix S1 for further detail regarding variables, variable calculations, and internal consistency of scale variables.

Reduced sleep/rest

Informants were asked in separate questions whether in the last year they had gotten (a) ‘less sleep than usual’ and (b) ‘less rest than [they] needed?’ Given the high correlations between these variables (r (218) = 0.585, P < 0.001 (spousal sample); r (136) = 0.667, P < 0.001 (CG sample)), they were combined such that informants were coded as yes = 1 to having reduced sleep/rest if they answered ‘yes’ to either question or coded as no = 0 if they responded ‘no’ to both questions.

PWCD frequent waking

Participants were coded as yes = 1 if the informant answered yes to ‘Does [the participant] wake a lot?’ This was an item from the modified Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q),35 used in the ADAMS informant questionnaire to assess the presence of neuropsychiatric behaviours in the participant over the last month.

PWCD dementia severity

This was assessed using the PWCD's Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) score (range = 0–5, with higher scores indicating greater impairment), consistent with Fisher et al. (2011).19, 36 Using information from both the PWCD and their informant about cognition and activities of daily living, the CDR score was assigned at the consensus conference after all evaluation information was reviewed.19

CG depression symptoms (sx)

Based on Fisher and colleagues' (2011) methodology,19 depression symptom scores were calculated using the sum of yes (=1) responses on three yes/no items from the modified Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale.

CG role overload

This can be conceptualised as caregiving role demands ‘spilling over’ to affect other relationship, occupational, health, and/or self-care demands and needs.37, 38 In the ADAMS informant questionnaire, informants were asked whether providing care for the participant affected, for example, leisure, vacations, other relationships, time for exercise, and time for healthcare in a series of yes/no questions. Scores (range = 0–7) were calculated using the sum of yes (=1) responses.

CG rewards

Consistent with Fisher and colleagues' (2011) methodology,19 CG rewards/benefits scores were calculated by summing the yes (=1) responses to five yes/no questions regarding beneficial or rewarding aspects of caregiving.

CG back-up care

Caregivers were considered to have back-up care if they responded ‘yes’ to the question, ‘If you were unable to provide this care for a week or so, (for example, due to illness), is there someone who would care for your friend or relative?’

Statistical analyses

IBM SPSS software (version 26.0) was used for data analyses.39 For the preliminary analysis, a forced-entry binary logistic regression examined the extent to which participant diagnostic status (CN (reference group) vs. CIND vs. dementia) was associated with spousal reduced sleep/rest (yes vs. no), after covarying for spousal age, gender (male = reference category), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White = reference category), and education (<12 years = reference category). To test Hypothesis 1, a forced-entry binary logistic regression examined the extent to which PWCD frequent waking, PWCD dementia severity, CG depression symptoms, and CG role overload were associated with CG reduced sleep/rest. Covariates included informant (caregiver) age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, cohabitation status (no = reference category), and number of days CG helped PWCD in the last month (continuous). The binary logistic regression used to test Hypothesis 2, was identical to the Hypothesis 1 analysis, except that CG rewards and CG back-up care were the primary predictors.

RESULTS

Preliminary study

The overall model predicting spousal reduced sleep/rest by participant cognitive diagnostic status was significant (X2 (9, n = 218) = 26.810, P = 0.002; see Appendix S1; Table S1), with spousal age, gender, education, and racial/ethnic identify included in the model. Specifically, as demonstrated in Fig. 1, spouses with a CIND partner were more likely to report the presence of reduced/sleep rest than those with a CN partner (odds ratio (OR) = 1.983, 95% CI: 0.987–3.984, P = 0.055), and spouses of a partner with dementia were even more likely to report the presence of reduced sleep/rest versus those with a CN partner (OR = 4.496, 95% CI: 1.877–10.767, P = 0.001). Additionally, across diagnostic statuses, non-Hispanic Black spouses had significantly higher rates of reduced/sleep rest relative to White spouses (P < 0.001).

Aim 1: Hypothesis 1

Among 136 CG of PWCD (a group that includes both CIND and dementia), 61.00% reported experiencing reduced sleep/rest in the previous year. The overall model predicting CG reduced sleep/rest by PWCD and CG factors was significant, XΧ2 (12, n = 136) = 31.876, P = 0.002), with CG age, gender, education, racial/ethnic identify, frequency of assistance, and co-dwelling status included in the model (see Appendix S1, Table S2 for detailed statistical results). Results indicated that increased CG role overload was significantly associated with CG reduced sleep/rest (OR = 0.669, 95% CI: 0.524–0.853, P = 0.001). There was a trend effect of increased CG depression symptoms being associated with increased report of inadequate sleep/rest (OR = 0.529, 95% CI: 0.271–1.035, P = 0.063) in the original model. Additional post-hoc testing revealed that CGs who endorsed reduced sleep/rest had higher levels of depression symptoms and higher CG role overload scores, with medium to large effect sizes (ps < 0.01), respectively, compared to CGs who did not endorse reduced sleep/rest (see Table 3). PWCD factors (i.e., PWCD frequent waking and dementia severity as measured by the CDR) were not associated with CG reduced sleep/rest.

| Predicting factor | Caregiver reduced sleep/rest? | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |

| Caregiver depression score, modified CES-D; d = 0.62* | 0.72 (1.06) | 0.19 (0.59) |

| Caregiver role overload; d = 0.88* | 3.73 (1.87) | 2.06 (1.92) |

- * P < 0.01.

- Data presented as mean (standard deviation); CG Depression Score ranges from 0 to 3 and CG Role Overload ranges from 0 to 7.

- CES-D, modified Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale; CG, caregiver; d, Cohen's d effect size.

Given the examination of spousal sleep problems in the preliminary study, we also explored factors predicting reduced/sleep rest within spousal caregivers only (n = 31). In a binary logistic regression predicting reduced sleep/rest (yes vs. no) by CG depression symptoms, CG role overload, PWCD frequent waking, and PWCD CDR score, the overall model revealed a trend effect (X2 (4, n = 31) = 9.390, P = 0.055); the only independent variable that approached significance was CG role overload (OR = 0.597, 95% CI: 0.352–1.012, P = 0.055). Although this analysis was underpowered due to small sample size, it indicates that role overload may play a significant role in the sleep of spousal CGs and non-spousal CGs of PWCD.

Aim 1: Hypothesis 2

There was a trend (P = 0.081; see Appendix S1, Table S3) in the overall model predicting CG reduced sleep/rest by caregiving rewards and the availability of back-up care. Subsequent exploratory analysis of individual model factors revealed a significant association between availability of back-up care and lower likelihood of CG reduced sleep/rest (P = 0.040 in the original model; see Table S3). Post-hoc Chi-square testing revealed that CGs were 7.901 times more likely (95% CI: 0.989–63.151) to have reduced sleep/rest if back-up care was not available versus if it was (X2 (1, n = 134) = 5.154, P < 0.023). Specifically, 91.67% of CGs without back-up care (n = 12) reported reduced sleep/rest, whereas only 58.20% of CGs with back-up care (n = 122) reported reduced sleep/rest.

DISCUSSION

In this secondary analysis of data collected from community-dwelling older adults in the U.S., we found that spouses of individuals with cognitive impairment are at increased risk of reduced sleep/rest relative to spouses of those who are CN. Specifically, 56.67% of spouses of those with dementia reported reduced sleep/rest over the previous year, versus 36.92% of spouses associated with CIND partners, versus just 21.14% of spouses with CN partners. While the underlying mechanisms between inadequate sleep and spousal cognitive decline are not clear, the literature on sleep problems in spousal caregivers of people with dementia has found that sleep interference may occur due to caregiving burden, caregiving role overload, depression, shifting relationship roles (e.g., spousal partners vs. CG and care-recipient), and/or decreasing social networks and support.17, 26, 40 These candidate mechanisms for reduced sleep/rest in the context of spousal cognitive decline warrant further investigation.

This study also identified that 61.00% of all informal primary CGs (not just spouses) of older adults with cognitive impairment reported reduced sleep/rest over the previous year. In the general U.S. population, 27.9% of adults report insufficient sleep or rest the majority of nights over the previous month,41 suggesting that CGs may be at greater risk of reduced sleep/rest compared to the general population (although of note the sleep/rest question wording slightly varies in the present study compared to the cited study). Additionally, among CGs of PWCD, it is CG-specific factors, rather than the PWCD-specific factors, that predict CG sleep problems. Namely, greater effects of caregiving on other aspects of life (e.g., relationship, health, and/or self-care needs and demands), higher CG depression symptoms (trend effect), and lack of perceived availability of back-up care were all associated with increased CG self-report of reduced sleep/rest. Frequent PWCD waking and dementia severity, as measured by the CDR, were not associated with CG sleep issues.

While the precise prevalence of insomnia and short sleep duration among caregivers of PWCD is not known, there is ample evidence that CGs of PWCD are at elevated risk of insomnia, shorter sleep duration, and poorer sleep quality relative to non-caregivers.15 Our results indicate that caregiver role overload, depression symptoms, and lack of perceived back-up help with caregiving are closely related to decreased sleep and inadequate rest, although we were underpowered to examine mediating relationships among these factors. Nonetheless, the results highlight the importance of assessing caregiving burden/role overload, mental health, and back-up care support when evaluating potential sleep problems among CGs of PWCD, in the broader context of caring for the PWCD-CG dyad. These data also suggest that role overload, depression, and back-up care support may be possible targets of intervention for CG who are getting insufficient rest or sleep.

Our results revealed that reduced CG sleep is closely aligned with the degree to which caregiving demands affect other aspects of life, such as reduced time for hobbies, vacations, family relationships, romantic relationships, exercising, seeking medical care when needed, and slowing down when ill. The mechanism for this is as yet unclear, but it is possible that increased stress and decreased available time mediate the relationship between CG role overload and reduced sleep/rest. Nonetheless, our findings point to the possibility that increasing caregivers' time for, and prioritisation of, leisure, other relationships, and their own health/wellness could have positive downstream effects on sleep. However, for caregivers to increase time spent on these non-caregiving activities, alternate care for the PWCD is needed.42 Therefore, interventions that foster increasing the care network and CGs' access to and utilisation of respite services could potentially promote improved sleep among CGs of PWCD. The need for back-up care is further supported by our finding that CGs were 7.901 times more likely to have reduced sleep/rest if they did not perceive having a back-up care option.

Outside of the primary aim, this study revealed several additional important findings. Living separately from the PWCD did not protect CGs from sleep problems, as there was no significant effect of cohabitation status on CG sleep. Neither cohabitation status nor frequent waking of the PWCD were associated with reduced CG sleep/rest, which suggests that nocturnal behaviours, disruptions, and needs of the PWCD are likely not driving reduced sleep/rest problems in this cohort of CGs. Further, although not a focus of this study, it was notable that regardless of participant diagnostic status, Black spouses were disproportionately more likely to report reduced sleep/rest, which is consistent with prior literature.43, 44 Some reasons for poorer sleep when compared with White counterparts may be due to downstream effects of systemic racism, oppression, and discriminatory policies that result in reduced access to socioeconomic and healthcare resources, which increases the risk of insomnia and reduced sleep.45

It is important to interpret this study's results in the context of its limitations. Primary variables were based on narrow measurement of independent variables. Specifically, reduced sleep/rest was measured with two yes/no questions, and CG depression symptoms, role overload, and rewards were all based on yes/no questions with restricted total score ranges (maximum range = 0–7), which may not capture sufficient variability and therefore underestimate the associations among variables. Additionally, the clinical meaningfulness of the group differences in scores is unclear. For example, given that a modified CES-D was used, the clinical significance of group differences in depression scores between CGs with and without sleep problems is unclear given that both group means were <1.0 on a scale of 0–3. More robust assessments of factors are needed in large studies to understand predictors of sleep problems among CG of PWD to inform intervention development and testing.

In summary, our findings indicate that sleep problems are common among spouses of those with cognitive decline, with a higher prevalence reported among spouses of those with dementia versus spouses of adults considered cognitively impaired, but functionally intact. Further, we found that CG factors (depression, role overload, perceived availability of back-up care) rather than factors in the person with cognitive decline (such as nighttime wakings) were the drivers of CG reduced sleep. Collectively, this suggests interventions are needed for caregiver sleep problems and identifies potential targets for intervention, including role overload, depression, and back-up care support.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Health Retirement Study The Aging, Demographics, and Memory at https://hrsdata.isr.umich.edu/data-products/aging-demographics-and-memory-study-adams-wave.