Community Nursing Practice in Hypertension Management in China: Qualitative Analysis Using a Bourdieusian Framework

Funding: This work was conducted as part of the author's funded PhD program at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, though no additional project-specific funding was provided for this study.

ABSTRACT

Objective

This study explores the practices of Chinese community nurses in hypertension management, using Pierre Bourdieu's theory of practice to understand how their routines are shaped by sociocultural and institutional forces, along with their professional dispositions.

Design

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted in Shenzhen, China, between March and June 2024, and is reported following the COREQ guidelines.

Sample

Eighteen nurses, each with at least 1 year of full-time experience in hypertension care within the local community healthcare system, were recruited from a participant pool established through prior research.

Measurements

Face-to-face individual semistructured interviews were conducted using a structured interview protocol, and data were analyzed through thematic analysis.

Results

Community nurses face tensions between traditional health beliefs and modern hypertension care, as well as institutional pressures that prioritize efficiency over personalized care. Power imbalances, particularly the authority of doctors, complicate their role. However, nurses adapt their care strategies through embodied practices, balancing clinical standards with patient needs.

Conclusions

Community nurses are not mere enforcers of guidelines but adaptive professionals who navigate complex sociocultural norms, institutional demands, and power dynamics in hypertension care. This study underscores the necessity for flexible, culturally sensitive practices to improve public health outcomes.

1 Introduction

Hypertension, or high blood pressure, is a chronic condition marked by persistently elevated arterial pressure, significantly raising the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other severe health issues. Affecting approximately 1.28 billion adults globally, nearly half of whom are undiagnosed and untreated (Farhadi et al. 2023), hypertension is one of the most prevalent noncommunicable diseases. Often called the “silent killer” due to its typically asymptomatic nature (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023), many individuals remain unaware of their condition until significant damage has occurred (Jacobs, Shah, and Bress 2022). The global prevalence of hypertension is rising, driven by aging populations, poor diets, physical inactivity, and increased stress (Sakakibara, Obembe, and Eng 2019). This condition profoundly impacts public health, contributing to millions of deaths annually and placing immense strain on healthcare systems worldwide .

Despite significant advancements in healthcare infrastructure, hypertension rates in China continue to rise, affecting nearly one-third of the adult population (Zhang et al. 2023). This trend is worsened by low awareness, inadequate treatment, and poor control rates (Wang et al. 2014). Contributing factors include rapid urbanization, dietary shifts toward high-sodium, low-nutrient foods, rising obesity, and decreasing physical activity (Attard et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2011). The growing burden of hypertension not only increases cardiovascular disease incidence but also imposes substantial economic challenges on China's healthcare system (Fan et al. 2023).

The WHO (n.d.) emphasizes the crucial role of primary care systems in preventing, detecting, and managing hypertension, advocating for accessible, community-based integrated care. Community healthcare is thus a cornerstone of effective hypertension management (Brownstein et al. 2007), a principle supported by the WHO (2018) and exemplified by successful models in the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service enables general practitioners and community nurses to collaborate in monitoring and managing hypertension, ensuring continuous, personalized care (Hawkins et al. 2012). Japan's healthcare system, known for its preventive focus, uses community health centers for regular screenings and lifestyle interventions, reducing hypertension rates (Inoue, Inoue, and Matsumura 2010). In the United States, the Million Hearts initiative highlights the importance of community-based outreach, education, and support programs in improving hypertension control (Frieden and Berwick 2011). Additionally, countries like Finland, Canada, and South Korea offer exemplary community-level hypertension management approaches (Feldman, Campbell, and Wyard 2008; Rosenthal 2014), reinforcing the WHO's directive that community healthcare is essential for accessible, sustained, and preventive care.

Hypertension management in China has transformed following the strategic shift from secondary to primary care and the introduction of basic public health services in 2009 (Hou, Meng, and Zhang 2016). This change, driven by the rising burden of chronic diseases like hypertension, aimed to prioritize primary care for disease prevention and management (Su et al. 2017). The 2009 health reforms integrated community healthcare providers into the national strategy, offering services such as regular check-ups, hypertension screening, patient education, and lifestyle promotion at the community level (Feng et al. 2015). The Healthy China 2030 initiative, launched in 2016, further emphasized primary care in managing chronic diseases (Pan, Wu, and Liu 2023). By promoting prevention, early intervention, and supportive community environments, this initiative has made community healthcare centers pivotal in reducing hypertension prevalence and improving overall population health.

Since 2009, extensive research has explored hypertension management at the community level in China, primarily focusing on two target populations. The first group, general practitioners, are often depicted as central figures in community healthcare (e.g., Chen et al. 2013; Shu, Wang, and Sun 2019; Zhang et al. 2019). This focus highlights their pivotal role in diagnosing, prescribing, and monitoring hypertensive patients, positioning them as principal gatekeepers of community health. Studies on their clinical decision-making, guideline adherence, and patient interactions have provided insights into the healthcare delivery system. However, this emphasis often overlooks the collaborative nature of community healthcare, where nurses play a crucial yet underappreciated role (Li and Chen 2023).

The second group comprises patients, with numerous studies highlighting the concept of “healthism” (Crawford 1980), which emphasizes personal responsibility for health management and behaviors (e.g., Gu et al. 2014; Li et al. 2019; Qu et al. 2019). This research has enhanced our understanding of patient compliance, health literacy, and behavioral factors in hypertension outcomes. However, by placing the burden of hypertension management “squarely” on individuals, these studies overlook structural and systemic barriers to effective self-management. Additionally, the uncritical application of healthism can reinforce a “blame-the-victim” narrative (Johnson et al. 2021), obscuring the need for comprehensive support systems within community healthcare.

Within the doctor-nurse-patient triangulation, community nurses have received relatively little attention in existing literature. Discussions on their role in hypertension management are primarily limited to service development and care evaluation (e.g., Miao, Wang, and Liu 2020; Zhu, Wong, and Wu 2014). While these studies highlight nurses’ roles in implementing protocols and evaluating interventions, they often reduce community nurses to mere executors of predefined tasks. This narrow focus overlooks the nuanced and dynamic ways nurses engage with patients and navigate institutional constraints, as well as the sociocultural context, power dynamics within healthcare teams, and the influence of nurses’ professional dispositions. Consequently, there remains a significant gap in understanding the lived experiences of community nurses and the complex, often invisible work they perform in managing hypertension.

To address this gap, it is crucial to examine community nurses’ hypertension management practices through Pierre Bourdieu's theory of practice. Bourdieu's framework, which explores the interplay between structure, agency, and habitus, provides a profound understanding of how community nurses’ routines are shaped by sociocultural and institutional forces, as well as their professional dispositions. This approach deepens our understanding of the social construction and sustainability of nurses’ practices, uncovering the underlying power dynamics and social norms that shape nursing care. Practically, the insights from this analysis can inform the development of more context-sensitive and effective hypertension management strategies, ensuring that the vital roles of community nurses are fully recognized and leveraged within China's evolving healthcare landscape.

2 Methodology

2.1 Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in Bourdieu's theory of practice. At the core of this theory is the concept of habitus, which encompasses the ingrained habits, skills, and dispositions individuals acquire through life experiences (Costa and Murphy 2015). Habitus represents a system of durable, transposable dispositions that guide how individuals perceive, think, and act within the social world (Lizardo 2004). Dispositions, integral to understanding habitus, are the tendencies and inclinations developed through socialization (Nash 2003). These durable yet adaptable dispositions influence how individuals respond to situations and navigate the social world (Bourdieu 2018).

Another key component of Bourdieu's theory is the field, a structured social space with its own rules and power dynamics (Hilgers and Mangez 2014). Within any field, individuals and groups vie for economic, cultural, social, and symbolic capital (Bourdieu 2018). These forms of capital are interconvertible and help individuals maintain or enhance their positions. The belief in the value of the stakes in a field, known as illusio, motivates individuals to compete for capital (Threadgold 2020). Doxa, another essential concept, refers to the taken-for-granted beliefs and values accepted as self-evident within a field (Myles 2004). Doxa shapes what is considered natural or normal and profoundly influences the habitus of individuals within that field.

Bourdieu's concept of practice encompasses actions and behaviors shaped by habitus and the field. Practices arise from the dynamic interplay between these elements, not merely as mechanical responses to stimuli.

Bourdieu's theory of practice offers a compelling framework for analyzing the role of community nurses in hypertension management. By highlighting the interplay between structure, agency, and habitus, this lens reveals that nurses’ actions are socially constructed practices embedded within the broader field of community healthcare. Habitus encompasses the ingrained professional dispositions and skills nurses acquire through experience, informing their patient care. These dispositions are shaped by sociocultural norms and institutional expectations. The concept of the field, with its structured power relations and resource distribution, elucidates the dynamics between nurses and other healthcare actors. As nurses navigate this space, they strategically deploy their social, cultural, and symbolic capital to assert their professional identities. This framework deepens our understanding of how nursing practices are reproduced and adapted, exposing the doxa—the implicit beliefs governing community healthcare. Through Bourdieu's approach, this study uncovers the power structures, sociocultural norms, and institutional constraints shaping nurses’ routines, contributing to a sociologically informed understanding of their roles in hypertension management.

2.2 Design and Setting

This study employed a qualitative descriptive design (Bradshaw, Atkinson, and Doody 2017), chosen for its ability to provide rich, detailed accounts of the nurses’ experiences and perspectives, and is reported in accordance with the COREQ guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig 2007).

This study was conducted in Shenzhen, a city known for its pioneering role in primary care development in China (Li and Chen 2023). By 2023, Shenzhen employed approximately 15,000 health professionals, including over 5000 registered nurses, across nearly 850 community health organizations (Public Hygiene and Health Commission of Shenzhen Municipality 2024). These resources make Shenzhen an ideal location for researching community nursing, facilitating fieldwork and data collection. Insights from Shenzhen can also inform other Chinese cities aiming to enhance their community healthcare systems (Li, Chen, and Howard 2023).

The choice of Shenzhen was further influenced by the urgent state of hypertension management in the city. Approximately 21% of Shenzhen residents suffer from hypertension, with awareness, treatment, and control rates at 54.34%, 43.48%, and 25.21%, respectively (Public Hygiene and Health Commission of Shenzhen Municipality 2020). Urbanization, stress from a fast-paced lifestyle, and unhealthy habits exacerbate these challenges. Addressing hypertension management practices in Shenzhen's community healthcare system is therefore crucial.

2.3 Sample

This study recruited 18 community nurses (Table 1), each with a minimum of 1 year of full-time experience in hypertension care within the local healthcare system. The participant pool was drawn from the author's previous work (Li and Chen 2023; Li, Chen, and Howard 2023), leveraging established professional connections. In March 2024, a research invitation was posted in a WeChat group of around 60 community nurses. Within a week, 23 nurses expressed interest in participating; however, five were excluded as they were no longer employed in Shenzhen's community healthcare organizations. Each participant received RMB 100 in cash as token appreciation for their contribution to the study.

| Male/Female, n | 3/15* |

| Age, mean (range) | 29.78 years (24–48 years) |

| Worked as a community nurse, n | |

| 1–5 years | 12 |

| 6–10 years | 5 |

| 11–15 years | 1 |

| Nurse categories, n | |

| General nurse | 15 |

| Specialist nurse | 3 |

- * The participants were drawn from a sample pool established in the author's previous research (Li and Chen 2023; Li, Chen, and Howard 2023), consisting of 67 community nurses, 12 of whom are male, representing approximately 18%, closely mirroring the 20% in this study. The minority presence of male nurses likely reflects the nature of community nursing, which does not demand the physical strength required in some hospital departments. Given the predominance of female nurses, the sample is considered both representative and well-suited, effectively capturing the experiences of the majority while ensuring the minority voices are acknowledged.

2.4 Data Collection and Analysis

Data for this study were collected through digitally recorded individual semistructured interviews, lasting between 67 and 112 min, conducted in designated consultation rooms within the participants’ workplaces to minimize unnecessary interruptions from March to June 2024. The interview guide (Table 2), informed by Bourdieu's theory of practice, facilitated an in-depth exploration of how professional practices are shaped by sociocultural norms, institutional expectations, and capital and power dynamics within the healthcare system. The interviews also addressed resource distribution and the formation of professional identities, revealing how nurses navigate the complexities of their roles in managing hypertension at the community level.

| Habitus and dispositions: |

|

| Field and institutional expectations: |

|

| Cultural and social capital: |

|

| Symbolic capital and power relations: |

|

| Doxa: |

|

| Sociocultural norms: |

|

- * The participants were drawn from a sample pool established in the author's previous research (Li and Chen 2023; Li, Chen, and Howard 2023), consisting of 67 community nurses, 12 of whom are male, representing approximately 18%, closely mirroring the 20% in this study. The minority presence of male nurses likely reflects the nature of community nursing, which does not demand the physical strength required in some hospital departments. Given the predominance of female nurses, the sample is considered both representative and well-suited, effectively capturing the experiences of the majority while ensuring the minority voices are acknowledged.

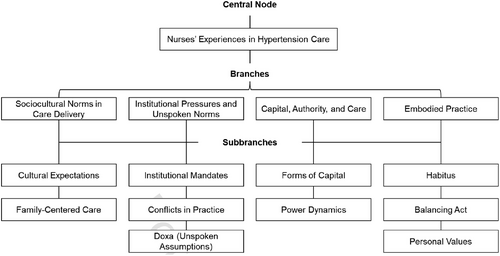

Thematic analysis was employed to analyze the data (Naeem et al. 2023). The process began with data familiarization, where interview transcripts and notes were meticulously reviewed to identify recurring patterns and key issues. Significant portions of the data related to nurses’ practices in hypertension care were then coded, followed by grouping these codes into broader themes that captured deeper insights into how nurses’ actions are shaped by their habitus, sociocultural norms, and institutional structures (Figure 1). Member checking was conducted with three participants to verify the accuracy and resonance of the identified themes with their experiences (Morse 2015). This involved presenting the themes back to the participants to ensure that they accurately reflected their perspectives, reinforcing the validity of the findings. Once the themes were refined and clearly defined, they were interpreted through the lens of Bourdieu's theory. Data saturation was achieved as no new themes or insights emerged from the interviews (Patton 2015). ATLAS.ti software was utilized to facilitate data management and analysis.

2.5 Ethics

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. To uphold privacy, participants were not asked to provide their names during interviews; instead, the standard code “IW” from qualitative research was employed to attribute specific quotes to respondents. Informed consent, either written or oral, was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Throughout the research process, data management, processing, and storage strictly adhered to institutional protocols for handling human subjects, thereby ensuring the ethical integrity and confidentiality of all participants.

3 Results

3.1 Sociocultural Norms in Care Delivery

This theme illuminates how nurses navigate the complexities of cultural expectations in care delivery. They endeavor to balance patient and community norms with clinical guidelines while confronting the challenges of harmonizing professional standards with the sociocultural values of the communities they serve.

A key belief influencing patients’ and their families’ preferences is “the traditional Chinese medical view that health depends on maintaining a balance between yin and yang forces” (IW7). This perspective often leads to “a preference for herbal remedies and natural treatments, as these are seen to restore bodily equilibrium” (IW10). Consequently, “some patients prioritize such alternatives over prescribed medications, perceiving them as more aligned with their overall well-being” (IW10). This belief can affect “patients’ receptiveness to modern hypertension treatments, particularly pharmacotherapy, which may be regarded as too forceful or inconsistent with natural healing principles” (IW5).

These deeply ingrained cultural beliefs profoundly shape the daily routines of community nurses, compelling them to adjust their clinical practices in hypertension care. For instance, a nurse encountered “a patient who rejected prescribed antihypertensive medications in favor of herbal remedies believed to restore the balance of yin and yang” (IW7). In response, the nurse “invested additional time educating both the patient and his families, explaining how pharmacotherapy can complement, rather than conflict with, traditional practices” (IW7).

Additionally, the strong emphasis on family-centered care in Chinese culture often conflicts with clinical protocols or decisions focused solely on individual patient health. As a result, nurses need to adjust their practices to be more culturally sensitive, sometimes at the expense of care quality. As one interviewee shared, “Mr. C, whose blood pressure had been dangerously high for weeks. According to clinical protocols, I recommended an immediate adjustment to his medication, including a stronger dosage and strict adherence to a salt-reduced diet. However, Mr. C's family, deeply rooted in the norms of family-centered care, insisted that they collectively decide on his treatment. […] They were concerned about the side effects of stronger medication and believed that certain traditional remedies and foods, seen as part of familial care, were more beneficial for his health” (IW17).

Caught between her professional responsibility and the family's influence, the nurse found herself in a challenging position. “The family's insistence on incorporating traditional foods, some of which were high in salt, conflicted with medical advice, yet I felt compelled to prioritize maintaining trust by reluctantly agreeing to a compromise that delayed the full implementation of the clinical treatment plan” (IW17). While this adjustment was culturally sensitive, “it led to a delay in Mr. C's progress” (IW17).

3.2 Institutional Pressures and Unspoken Norms

This theme examines how institutional forces—comprising both formal policies and implicit norms within the healthcare field—shape the daily routines of community nurses in hypertension care.

Nurses operate within a structured environment governed by institutional mandates, such as performance metrics, clinical guidelines, and resource allocation. These factors influence their approach to care, determining everything from the time spent with patients to the prioritization of specific treatments. As one interviewee explained, “We are expected to see a certain number of patients each day, follow strict clinical guidelines, and document every step of the process. This leaves very little room for personalizing care to meet the specific needs of patients” (IW12). Another noted, “The system prioritizes efficiency and numbers, so while I try to spend more time with patients to understand their challenges, I often have to cut the interaction short because we are evaluated based on how many patients we see, not necessarily on the quality of care” (IW6).

This theme also addresses the conflicts that arise when nurses’ professional practices in hypertension care intersect with the demands of the healthcare field, where institutional guidelines and patient needs may clash. Nurses frequently struggle to reconcile stringent policies—such as mandated medication protocols and administrative documentation requirements—with the individual needs of patients, who may require more personalized or flexible care. As one interviewee observed, “In my clinic, we adhere to a strict medication regimen for hypertension, but I had a patient who suffered severe side effects from the standard treatment. Although I recognized that an alternative medication might have been more appropriate, I was bound by protocol and could not adjust his treatment without risking noncompliance with the guidelines. […] It was a challenging decision between adhering to institutional rules and addressing his immediate health needs” (IW9). Another interviewee shared, “We are mandated to complete a specific number of administrative tasks each day, which often reduces the time available for direct patient care. For example, I had a patient, Ms. L, who required extensive counseling and adjustments to her treatment plan due to her unique situation. However, due to administrative pressures, I had to expedite her appointment, knowing that this rushed approach did not fully address her needs or the complexity of her case” (IW2).

Furthermore, this theme highlights how doxa—the unspoken assumptions and norms embedded in the field—subtly shapes nurses’ work in hypertension care. Specifically, within their professional environment, nurses encounter unspoken rules that guide their actions, such as the implicit expectation to adhere to institutional protocols without questioning them. These assumptions are deeply ingrained in the field and often go unchallenged. “There is an unspoken rule that we must prioritize efficiency over patient interactions, which often limits the time we can spend addressing individual needs” (IW7). Another commented, “We are expected to follow protocols rigidly, even if it means not fully addressing a patient's unique situation. Questioning these protocols feels risky” (IW13). One more interviewee highlighted, “The norm is to adhere to standardized treatment plans without deviation. I have noticed that stepping outside these boundaries can be frowned upon, even when it might benefit the patient” (IW5).

3.3 Capital, Authority, and Care

This theme examines how nurses’ routines are shaped by field-related forces of capital and power, emphasizing how their knowledge, professional relationships, and hierarchical structures influence their ability to manage hypertension care. It underscores the tension nurses experience as they navigate a healthcare system that often privileges other forms of capital, such as the authority held by doctors or institutional frameworks.

Cultural capital, represented by nurses’ expertise and clinical skills, enables them to deliver effective care, yet it is frequently undervalued in comparison to doctors’ authority. As one nurse shared, “Despite my years of experience and specialized training in hypertension, patients still often defer to the doctor for final approval, even when I have already laid out the plan” (IW4). Similarly, symbolic capital, the status and respect nurses command, plays a crucial role in care delivery but is often overshadowed by the authority of doctors. “Even though I am the one who spends the most time with patients, they see the doctor's advice as more legitimate. It sometimes feels like my role is just to carry out instructions rather than make clinical decisions myself” (IW7).

On the other hand, social capital—the relationships nurses build with colleagues and patients—fosters stronger connections, enhancing communication and trust. However, it also introduces challenges, particularly when patients expect personalized or informal care that may conflict with standardized treatment protocols. As one nurse noted, “Because I have built strong relationships with some patients, they feel comfortable coming to me with every concern, expecting quick adjustments to their treatment, even if it goes against the standardized care plan” (IW8).

This theme also explores the tensions arising from power imbalances in healthcare, particularly how nurses navigate hierarchical structures that prioritize the authority of doctors and institutional protocols. Nurses often struggle to assert their symbolic capital, as both patients and colleagues tend to view doctors as the primary decision-makers. One nurse reflected, “Patients listen, but their trust in my expertise often depends on a doctor's confirmation. Even though I have handled many hypertension cases, my advice sometimes feels secondary until a doctor agrees” (IW10).

These power dynamics can lead to frustration, especially when nurses feel their cultural capital—represented by their knowledge and clinical skills—is overlooked. As another nurse recounted, “There was a case where I knew the patient needed a different medication, but I had to wait for the doctor's approval. The delay in getting this approval meant the patient's condition likely worsened, which was difficult to watch” (IW3).

3.4 Embodied Practice

This theme examines how nurses’ routines in hypertension care are shaped by their habitus—deeply ingrained dispositions, values, and beliefs developed through personal and professional experiences. Rather than being solely dictated by external factors such as protocols or patient needs, nurses’ actions are profoundly influenced by their internalized frameworks, which shape their perceptions, decisions, and interactions.

Nurses frequently draw on their lived experiences to inform clinical judgment and build empathy with patients, relying on instincts honed in both personal and professional contexts. One interviewee shared how growing up in a family with a history of hypertension heightened her sensitivity to patient anxieties and noncompliance: “My father had hypertension, and I remember how difficult it was for him to manage it. That experience makes me more patient with older individuals who struggle to follow strict medication routines. […] I always think about what worked for my dad when I advise patients” (IW2).

Moreover, nurses’ habitus, shaped through years of professional socialization, influences how they balance empathy, efficiency, and clinical judgment in managing hypertension cases. Their disposition to care is reflected in how they navigate the tension between institutional demands and patient-centered care, often shaping their approach to challenges in care delivery. “I have learned over the years to be firm but understanding with patients. You need to build trust, but at the same time, I have internalized the importance of following protocols. It is a balancing act between care and discipline” (IW14).

Nurses may also adjust their care strategies to align with their ethical values, sometimes prioritizing holistic well-being over rigid adherence to medical guidelines when it benefits the patient. This reflects how personal values such as compassion, patience, and respect for tradition shape their approach to hypertension management. “For me, it is important that the patient feels heard. I believe that if they trust you, they are more likely to stick with the treatment plan. So, even when time is tight, I make sure to listen to their concerns—it is part of my values as a nurse” (IW17).

4 Discussion

Drawing on Bourdieu's theory of practice, this study uncovers the complexities of nurses’ roles in hypertension care within the Chinese community healthcare context through four key themes: “sociocultural norms in care delivery,” “institutional pressures and unspoken norms,” “capital, authority, and care,” and “embodied practice.”

The first key finding highlights how deeply rooted sociocultural norms, such as the traditional Chinese health belief in balancing yin and yang, shape patient preferences and care decisions. Community nurses frequently encounter patients who favor herbal remedies or family-centered care over pharmacotherapy. This adds nuance to discussions of patient-centered care by revealing the tension between cultural respect and clinical guidelines, challenging the assumption that patient adherence can be improved solely through clinical education (Morisky et al. 1990; Smrtka et al. 2010). Indeed, community nurses serve as mediators between competing belief systems, balancing cultural sensitivity with professional responsibility.

Another significant finding shows how institutional pressures, like performance metrics and rigid clinical guidelines, constrain community nurses’ ability to provide personalized care. While standardized protocols are often seen as promoting efficiency and quality (Rycroft-Malone et al. 2008), this study reveals their hidden costs. Nurses report that institutional demands limit their time with patients, compromising care quality. This finding challenges the notion that protocol-driven care is inherently superior (Ilott et al. 2006; Vardaman et al. 2012), highlighting how unspoken norms within healthcare systems can undermine patient well-being.

The third theme underscores the power imbalances between community nurses and doctors, which limit nurses’ autonomy in care delivery. Despite nurses’ expertise, their symbolic capital is often overshadowed by doctors, complicating their clinical decision-making. This finding challenges the view that nursing expertise is increasingly valued in healthcare (Dickson, McVittie, and Kapilashrami 2018), exposing the persistence of hierarchical structures that diminish nurses’ authority and delay patient care when they must wait for doctors’ approval.

Finally, the study emphasizes the importance of community nurses’ embodied practices—their internalized dispositions, values, and experiences—in shaping their approach to hypertension care. Nurses’ roles extend beyond technical duties; they adapt care strategies by balancing empathy, efficiency, and clinical standards, drawing from both personal and professional experiences. This finding challenges the reductionist view of nursing as purely technical (Bull and FitzGerald 2006), enriching discussions of holistic care in nursing (Windsor, Douglas, and Harvey 2012) by showing the complex interplay between clinical knowledge and patient-centered values.

Together, these findings challenge the traditional, one-dimensional view of nursing as a technical support role within a hierarchical system. Instead, they reveal nurses as adaptive professionals who navigate cultural beliefs, institutional demands, and power imbalances to meet clinical standards and patient needs. This study enriches the discourse on community health services by providing a nuanced understanding of the critical role community nurses play in hypertension care.

The findings of this study carry profound implications for global public health nursing, highlighting the need for approaches that are sensitive to the complexities of sociocultural norms, institutional pressures, and power dynamics in care delivery. Grounded in Bourdieu's theory of practice, the study reveals that community nurses are not passive enforcers of clinical protocols but adaptive professionals navigating the intersection of clinical standards and patients’ cultural values. This insight is relevant for public health nursing globally, where cultural diversity and varying healthcare systems pose unique challenges (Douglas et al. 2011). The study underscores the importance of flexibility in nursing practice, advocating for healthcare systems that empower nurses to exercise autonomy and tailor care to the specific cultural and social contexts of their patients. By recognizing nurses’ embodied practices and their critical role in mediating between cultural sensitivity and clinical rigor, the research calls for a paradigm shift toward more holistic, culturally competent, and patient-centered care. These findings offer valuable insights for global public health initiatives aimed at improving chronic disease management, particularly hypertension care, by fostering more inclusive and responsive healthcare environments.

4.1 Limitations

This study has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, its focus on community nurses in China may not fully capture the experiences of nurses in other countries, where different sociocultural and healthcare systems exist. Additionally, the qualitative approach, while providing rich insights, may lead to subjective interpretations or biases in responses. The reliance on nurses’ self-reported experiences could also introduce recall bias. Furthermore, the study concentrates on hypertension care, which may limit the applicability of findings to other health conditions or clinical settings, reducing the overall scope of the conclusions.

5 Conclusion

This study elucidates how community nurses navigate the intersecting forces of sociocultural norms, institutional pressures, and power dynamics in delivering hypertension care within Chinese communities. Drawing on Bourdieu's theory of practice, it reveals that community nurses are not mere passive implementers of clinical guidelines but adaptive professionals whose routines are shaped by their internalized habitus and lived experiences. The findings challenge reductionist views of nursing, highlighting its complexity and the pivotal role nurses play in mediating between cultural beliefs and clinical standards. Practically, the study underscores the need for healthcare systems to adopt more flexible, culturally sensitive approaches that acknowledge the unique contexts in which nurses operate. By creating environments that value community nurses’ expertise and empower their autonomy, healthcare institutions can improve hypertension management and public health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Sincere gratitude to the nurses who generously shared their time and insights during the interviews. Special thanks to the Department of Applied Social Sciences at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University for providing financial support during the fieldwork.

Ethics Statement

The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Institutional Review Board ethically approved the research (reference HSEARS20210417003).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Participants were assured that the raw data would remain confidential and not be shared with the public. Additional information is available upon request.