Nursing and Social Justice—A Scoping Review

ABSTRACT

Background

Nursing is historically, ethically, and theoretically mandated to champion social justice.

Objective

To investigate how the concept of “social justice” has been explored in nursing research regarding extent, range, and nature.

Methods

The five-stage framework by Arksey and O'Malley was adopted, and JBI and PRISMA guidelines further informed the study. The search strategy comprised three steps: an initial search, a systematic search in several databases, and finally, a reference, citation, and gray literature search. A total of 55 studies meeting the inclusion criteria were included in the analysis.

Results

Almost all the included studies were authored in the English-speaking world. Most studies were published from 2014 onward, and qualitative methods were by far the most prominent. A total of 13 specific definitions or understandings of social justice were identified. Five themes were identified across the included studies: (1) education, (2) concept, (3) theory, (4) public health and community nursing, and (5) maternal and child health.

Conclusion

The literature on social justice and nursing is limited, albeit growing. The conceptualization of social justice within nursing is becoming broader and more nuanced. Only a few studies have focused on specific patient groups or specialties.

1 Introduction

Nursing has a long history of advocating for and promoting social justice (Abu 2020; Boykin and Dunphy 2002; Rudner 2021; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017). One could argue that modern nursing emerged in response to inequity and, from its inception, aimed to mitigate the consequences of injustice faced by the less fortunate (Rudner 2021; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017). Before the advent of modern nursing, caring for the sick and impaired fell primarily upon family members or religious or charitable entities. Only the wealthy could afford professional assistance from doctors and nurses, whereas others relied on untrained attendants to provide care (Helmstadter 2011). Florence Nightingale started to change that when she and others spearheaded modern nursing as a professional discipline and thus championed health rights (Abu 2020; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017).

Social justice is often understood as fairness and equality for everyone. However, definitions have evolved to encompass new insights and perspectives. Today, social justice is usually seen as more than “just” the equal distribution of societal benefits and burdens. The focus has shifted from equality to equity, acknowledging that individuals have different needs and abilities (Braveman 2014).

Globally, health disparities are rising (World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe 2019). Disparities are often rooted in underlying social injustices, including unequal access to resources, discrimination, poverty, and marginalization (Braveman et al. 2011; Marmot 2017). Social injustice and health inequity are closely intertwined concepts that significantly impact individuals’ and communities’ well-being (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2017). Health inequities refer to unfair and avoidable differences in health outcomes, systematically shaped by social, economic, and environmental factors (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2017). Recognizing, acknowledging, and advocating for addressing the problem of inequity and injustice in health requires acting on the root cause: the social determinants of health (CSDH 2008; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021; Reutter and Kushner 2010). The World Health Organization (2008) defines social determinants of health as “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age.” In their groundbreaking final report, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health of the WHO (2008) stated that “social injustice is killing people on a grand scale.” It emphasized that tackling social determinants of health is crucial. However, more than 15 years later, the recommendations of the report have not generated the desired action (Rasanathan 2018). Even so, recent events, such as the Black Lives Matter movement and the COVID-19 pandemic, have highlighted the impact of social injustice on the health and well-being of individuals, families, and communities (Ali, Asaria, and Stranges 2020; Bowleg 2020; Devakumar et al. 2020; Rudner 2021).

Today, social justice is named in declarations, statements, and codes of ethics from the International Nursing Council (ICN) and a wide range of national nursing organizations. In their 2013–2017 strategic framework, the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council (2013) specified social welfare and social justice as one of the areas in which they would seek to provide leadership. Similarly, the Canadian Nurses Association (2010) initiated a policy discussion entitled “Social justice… means to an end or an end in itself” to encourage debate and support the development of equitable programs, policies, and products. Furthermore, in their code of ethics, the ICN (2021), the American Nurses Association (2015), and the Danish Nursing Counsel (2014), among many others, specify that nurses are mandated to champion health rights and social justice for all. Additionally, the American (2016), Canadian (2005), and New Zealand nursing organizations (2013, 2018) address the need for social justice and health equity for minorities and disadvantaged groups within their respective societies. In their statements, policies, and codes of ethics, all the above-mentioned national nursing organizations and many others advocate that nursing and care must be allocated to all, according to their needs and without bias from social status, race, financial capabilities, and so forth. Care according to need is also advocated in the body of nursing theory. Even so, the term social justice is rarely explicitly named. This in no way means that the notion of social justice is absent; in nursing theory, social justice has often been addressed through calls for context awareness in nursing (Chinn and Kramer 2018; Kagan et al. 2010), holistic care (Kreitzer and Koithan 2019; Martinsen 2000), and equity as a foundational value (Martinsen 2000; Watson 2018). Nurses champion social justice by raising awareness of unjust structures and mechanisms in healthcare and society at large. They advocate for social justice policies and engage in shaping healthcare through the development of practices, programs, and interventions that promote health equity. Additionally, in their everyday practice, nurses lead by example and educate future nurses with an ethical responsibility grounded in social justice principles (American Nurses Association 2015; Canadian Nurses Association 2010).

During many years of focusing on the instrumental, measurable, evidence-based, and technological aspects of nursing, only limited attention has been devoted to the societal and structural aspects of health and well-being (Rudner 2021; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017). However, within nursing, awareness is growing of the role and mandate of the nursing profession to address the root causes of health inequity. This rise is witnessed by the influx of editorials and “calls for action” by nurses from practice, academia, and education (Abu 2020; Jackson et al. 2021; James, Carrier, and Watkins 2021; Roush 2011; Willgerodt et al. 2021). Despite this recent trend and the historical, organizational, ethical, and theoretical foundation of social justice in nursing, the nursing profession still lacks a comprehensive understanding and clear definition of social justice and ways and strategies for action (Abu 2020; Boutain 2020; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017).

Nurses are the largest group of healthcare providers (Mitchell, Wilson, and Jackson 2019). It is increasingly recognized that they are key figures in securing equitable health outcomes (Andermann 2016; Reutter and Kushner 2010), improving population health (Fawcett and Ellenbecker 2015), and addressing social determinants of health (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2021; National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice 2020; Reutter and Kushner 2010; Smith 2007). If nurses do not critically appraise the impact of social and environmental determinants on patient health and health behaviors, they will be left to treat and care for symptoms of health disparities rather than tackle the root causes—social injustice and inequity (Mitchell, Wilson, and Jackson 2019). Therefore, nurses must be aware of their mandate to champion health rights and social justice and have the knowledge, tools, and competence to do so. Research on social justice and nursing may pave the way for a greater understanding of how social determinants of health influence treatment and care. Nursing research on social justice can also influence policy and inform the development of interventions while sensitizing and educating nurses and nursing students on how social structures influence health and healthcare.

A preliminary search of MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and JBI Evidence Synthesis was conducted to identify any upcoming or current systematic or scoping reviews on social justice and nursing. None were found. A book chapter (Boutain 2020) containing a literature review on social justice in nursing was identified through Google Scholar but the review focused exclusively on conceptualization, and the literature search performed was limited to a single database. Two reviews (Elliott and Sandberg 2021; Shahzad et al. 2022) on social justice and nursing education were identified. However, both were integrative reviews focused on teaching undergraduate nursing students about social justice.

The lack of a comprehensive understanding of the full scope of the existing literature challenges the process of identifying gaps in the current knowledge base and, thus, focus areas for future research. As no current overview, synthesis, or map exists of the present knowledge base in nursing research on the topic of social justice and nursing in general, this scoping review explored how the concept of “social justice” has been explored in nursing research regarding extent, range, and nature.

2 Design and Method

A scoping review was conducted to map the existing research literature on social justice and nursing regarding extent, range, and nature. Scoping reviews offer a way to map the literature in a field, thereby creating an overview of the existing knowledge (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Lockwood and Tricco 2020; Peters et al. 2020; Pollock et al. 2021). Scoping reviews are ideal when asking broad questions or identifying knowledge gaps, conceptual boundaries, and key concepts and characteristics of a theme (Arksey and O'Malley 2005; Lockwood and Tricco 2020; Peters et al. 2020). They are recommended for exploring how research has been conducted regarding a theme or concept and for investigating the nature and diversity of knowledge (Peters et al. 2020). Therefore, scoping reviews often pave the way for other types of systematic reviews addressing more specific research questions identified through the knowledge overview established in a scoping review (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). After initial searches on social justice and nursing, it became evident that the literature on social justice and nursing is diverse and complex and that no comprehensive overview or map had been made. A scoping review was, therefore, deemed an appropriate review design for the present study.

This scoping review was conducted adopting the five-stage approach proposed by Arksey and O'Malley (2005). Stages 1–4 are presented in Section 2, while Stage 5 is presented in Section 3. Their approach was chosen because it offers a framework for conducting a scoping review while leaving room for reflexivity and allowing for decision-making by the research team. Furthermore, the JBI methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2020) was used for guidance and support as it offers more detailed and specific recommendations and guidelines for each step of the review process. The scoping review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al. 2018).

Scoping reviews are iterative, and researchers will go back and forth between the steps of the approach (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). As the initial searches are conducted, researchers become more oriented and informed about the existing literature, the search strategy, and eligibility criteria and therefore need to go back and refine, redefine, or change certain aspects. In line with recommendations by Arksey and O'Malley (2005), this scoping review was conducted rigorously and transparently and documented in sufficient detail to strengthen its validity and trustworthiness (Arksey and O'Malley 2005). A detailed description of the procedure used to conduct each of the five stages of the scoping review is presented in the following sections. A protocol for this scoping review was registered with the Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HTP3W).

2.1 Stage 1: Identifying the Research Question

The objective of a scoping review should be linked to its rationale (Tricco et al. 2018). The rationale for this scoping review is that nurses are mandated to push for health equity and social justice in practice, education, leadership, policy, and academia. For nurses to take up this challenge, knowledge of social justice is needed to inspire nurses in various practices by providing an overview of potential ways, interventions, strategies, and so forth, by which they may address social injustice. This scoping review may also inform future nursing research on the current state of the research field and assist in identifying gaps and unexplored areas.

The overall aim of this scoping review is as mentioned earlier: How has the concept of “social justice” been explored in nursing research concerning extent, range, and nature?

This scoping review was guided by the following specific questions:

Extent: How many studies have been published on social justice and nursing? When were the studies published?

Range: Where are studies on social justice and nursing published in terms of geography and journals? In which specific population groups, specialties, or contexts are studies on social justice and nursing rooted?

Nature: What research methods have studies on social justice and nursing used? Which definition or understanding of social justice do studies on social justice and nursing have?

2.2 Stage 2: Identifying Relevant Studies

2.2.1 Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate published and unpublished sources and comprised three steps in accordance with the JBI guidelines (Peters et al. 2020).

First, a preliminary limited search was conducted in Medline via PubMed and CINAHL Complete, using the terms “social justice” and “nursing.” This search aimed to identify sources relevant to the scoping review that could guide the full search strategy. As a result of the preliminary limited search, we decided that the term “social justice” should be present in either the title or abstract of sources considered for this scoping review. We made this decision because social justice seemed to be a popular keyword used in many articles that did not address “social justice.”

The second step was a full search of CINAHL Complete, Medline (PubMed), Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, APA PsycInfo, and Academic Search Premier using the search terms “social justice” (title/abstract) and “nurse” or “nursing” (all fields) (Table 1). In Scopus, the search strategy was slightly modified as the search term “nurse” or “nursing” needed to be present in the title or abstract. We chose this because initial searches in Scopus yielded a considerable number of hits, many unrelated to nursing. A broad approach was deliberately used in the search strategy, with few search blocks and limits to ensure breadth of coverage. Google Scholar, Open Dissertations, ProQuest, Ethos, and Open Grey were also searched to identify potentially relevant sources. We used the same search terms as in the literature databases and manually revised the results. In Google Scholar, we sorted by relevance and revised the first 500 hits as the search returned a very high number of hits. The final literature search was conducted in June 2022.

| (nursing OR nurse) AND (TI social justice OR AB social justice) |

The third step involved conducting citation and reference searches on the sources selected for inclusion in the scoping review to uncover potentially relevant sources missed in the full database search.

2.3 Stage 3: Study Selection

Following the search, all identified sources were collated and uploaded to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation), a web-based collaboration software platform that streamlines the production of literature reviews. Duplicates were removed following the upload.

Eligibility criteria were set within four areas inspired by the JBI manual for evidence synthesis (Peters et al. 2020): participants/population, concept, context, and type of sources.

2.3.1 Participants/Population

No specific criteria for participants or populations were used in this scoping review.

2.3.2 Concept

As the concept of social justice in nursing research still lacks a clear, consistent, and occasionally explicit definition (Boutain 2020), no specific definition was used as an eligibility criterion. The scoping review considered all sources in which the term “social justice” was included in the title or abstract.

2.3.3 Context

This scoping review considered all sources from the nursing context, and only sources rooted within a nursing context were considered. All nursing areas were considered in terms of clinical specialties and settings (e.g., hospital, home care, nursing home, etc.).

2.3.4 Types of Sources

This scoping review considered all original research, both empirical and theoretical. Sources include research articles and PhD dissertations. Non-research sources, such as editorials, opinion papers, essays, and non-scientific articles, were excluded as the review questions relate specifically to nursing research.

2.3.5 Selection Process

The author team screened and selected the identified sources and reviewed each potential source to ensure congruity with each inclusion criterion. The process was divided into two stages.

First, a screening and selection process pilot was completed to ensure consistency with each inclusion criterion. For the pilot, 10 sources were selected using random selection, and the author team independently screened all sources using an a priori eligibility criteria list. Next, the author team met to discuss potential discrepancies regarding which sources should be included and excluded and possible needs for rewording or modifications to the eligibility criteria list. Subsequently, two members of the author team used Covidence to assess all sources for inclusion using the updated eligibility criteria list. AT was consistently involved in the process and assessed all sources. HEA, BH, and LWQ each assessed one-third of the sources. Covidence documented potential source selection conflicts, and the two reviewers who had assessed the source met to discuss and resolve any dispute. Generally, sources were included for full-text screening if they were deemed challenging to assess due to insufficient or ambiguous titles or abstracts and in cases of unresolved conflicts or doubts among the author team. This is to avoid leaving out potentially relevant sources at this early screening stage.

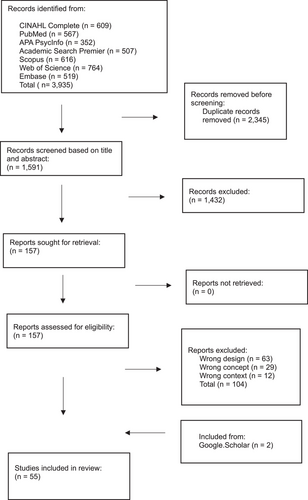

The second step involved identifying potentially relevant sources by reviewing the full text. The full text of selected sources was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria. AT reviewed all texts, and HEA, BH, and LWQ each reviewed one-third. The entire selection process is illustrated in the flow chart presented in Figure 1.

Two dissertations identified as relevant through database searches were not included because articles based on their findings had already been included. One book chapter known to the authors from their initial investigation of the field was returned as the first hit in the Google Scholar search. Furthermore, a relevant PhD dissertation was identified through Google Scholar.

2.4 Stage 4: Charting the Data

After selecting the sources for the scoping review, they were charted by stating various details, including author, title, publication year, journal, research question, definition of social justice, country of study, method, result, and conclusion. The chart form was developed through discussion with the author team. We included themes that could inform us on “extent, range, and nature” and thereby allow us to answer the research question. The chart form also included a column for adding notes on possible themes, notes for analysis, comments on the quality of the source, and so forth. Unlike systematic reviews, scoping reviews typically do not include quality assessment and formal appraisal of included sources, and this scoping review follows that norm (Peters et al. 2020). However, notes were taken on the overall quality of each source to be used for reflection, discussion, and determination of the “nature” of the knowledge reported.

3 Results

3.1 Stage 5: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

In total, 157 sources were eligible for full-text screening, and 55 were included in the final overview (see Figure 1 for a flowchart).

The following presents the extent, range, and nature of the included sources by examining their characteristics in terms of type, year published, country of origin, methods, and journal of publication. Then, an overview of definitions and understandings of social justice in the included sources is presented. Last, five main themes identified in the 55 sources are presented as education, concept, theory, community and public health nursing, and maternal and child health.

3.1.1 Study Characteristics

Among the 55 included sources, 51 were journal articles, one was a book chapter, and three were PhD dissertations. Eight journals have published more than one study included in this scoping review (Table 2). Advances in Nursing Science was the journal that published the largest number of included studies. Advances in Nursing Science aims to “advance the development of nursing knowledge and to promote the integration of nursing philosophies, theories and research with practice.” The journal seeks to publish pioneering articles that can add to the evolution of nursing while recognizing aspects such as class and race. The 13 studies published in Advances in Nursing Science mainly focused on theory, concept, discourse, and policy—often adopting a critical and intersectional viewpoint. Nursing Inquiry published a total of seven included studies. This journal focuses broadly on “ideas and issues pertaining to nursing and health care.” It also aims to be a vehicle for critical reflection to foster debate and dialogue and advance conceptualization. The seven studies published by Nursing Inquiry cover a broad field within social justice research encompassing concept, theory, practice, and education. Five of the included studies were published in Public Health Nursing. This journal publishes studies focusing on public health from a broad perspective, including studies focusing on education, practice, policy, history, ethics, theory, and methodological innovations. The five studies published in Public Health Nursing deal with social justice regarding concept and education. Four of the included studies were published in Nursing Ethics, which “takes a practical approach to this complex subject and relates each topic to the working environment.” The four studies are comprehensive and apply a variety of methods.

| Journal | Studies | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Advances in Nursing Science | Anderson et al. (2009); Bekemeier and Butterfield (2005); Falk-Rafael (2005); Falk-Rafael and Betker (2012); Kirkham and Browne (2006); Lind and Smith (2008); MacKinnon and Moffitt (2014); Perry et al. (2017); Ray and Turkel (2014); Thompson (2014); Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe (2017); Walter (2017); Velasco and Reed (2023) | 13 |

| Nursing Inquiry | Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe (2018); Browne and Tarlier (2008); Cuthill (2016); Macleod and Nhamo-Murire (2016); Nissanholtz–Gannot and Shapiro (2021); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2020); Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter (2015) | 7 |

| Public Health Nursing | LeBlanc (2017); Matwick and Woodgate (2017); Shearer (2017); Valderama-Wallace (2017); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019) | 5 |

| Nursing Ethics | Garcia (2021); Hosseinzadegan, Jasemi, and Habibzadeh (2021); Mooney-Doyle, Keim-Malpass, and Lindley (2019); Nesime and Belgin (2022) | 4 |

| Nurse Education Today | Scheffer et al. (2019); Shahzad et al. (2022) | 2 |

| Nursing Outlook | Grace and Willis (2019); Nemetchek (2019) | 2 |

| International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarships | Cohen and Gregory (2009); Kirkham, Van Hofwegen, and Hoe Harwood (2005) | 2 |

| Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing | Clingerman and Fowles (2010); Logsdon and Davis (2010) | 2 |

| Policy, Politics, and Nursing Practice | Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019) | 1 |

| Journal of Caring Science | Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi, and Javaheri Tehrani (2022) | 1 |

| Nursing Leadership (Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership) | Matwick, Martin, and Scruby (2021) | 1 |

| Nursing Philosophy | Kagan et al. (2010) | 1 |

| Journal of Forensic Nursing | Hellman et al. (2018) | 1 |

| BMC Nursing | Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan (2021) | 1 |

| Nursing Education Perspectives | Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels (2011) | 1 |

| Nursing Research | Giddings (2005) | 1 |

| Journal of Nursing Education | Elliott and Sandberg (2021) | 1 |

| Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing | Dysart-Gale (2010) | 1 |

| Nursing Forum | Davis et al. (2020) | 1 |

| Nurse Educator | Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy (2022) | 1 |

| Neonatal Intensive Care | Caldwell and Watterberg (2015) | 1 |

| Journal of Advanced Nursing | Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo (2012) | 1 |

The overwhelming majority of the included studies were from the United States, 33 in total. We determined the geographical origin of the included studies by identifying where the data collection (if any) occurred or by establishing with which institutions the authors of the article were affiliated. Therefore, some studies have more than one country of origin. Besides the United States, Canada had the largest number of included sources, a total of 15. The United Kingdom and Iran were the only other countries with more than one source included; both recorded three included sources. New Zealand, South Africa, Pakistan, and Israel each had one source included (Table 3).

| Country | Studies | Total |

|---|---|---|

| United States | Anderson et al. (2009); Bell (2017); Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo (2012); Caldwell and Watterberg (2015); Clingerman and Fowles (2010); Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy (2022); Davis et al. (2020); Elliott and Sandberg (2021); Garcia (2021); Giddings (2005); Grace and Willis (2012); Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels (2011); Hellman et al. (2018); Kagan et al. (2010); LeBlanc (2017); Logsdon and Davis (2010); Matwick, Martin, and Scruby (2021); Matwick and Woodgate (2017); Mooney-Doyle, Keim-Malpass, and Lindley (2019); Perry et al. (2017); Ray and Turkel (2014); Scheffer et al. (2019); Shearer (2017); Thompson (2014); Thuma-McDermond (2011); Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe (2017); Valderama-Wallace (2017); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019, 2020), Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019), Walter (2017), Velasco and Reed (2023), Boutain (2020) | 33 |

| Canada | Anderson et al. (2009); Bekemeier and Butterfield (2005); Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe (2018); Browne and Tarlier (2008); Cohen and Gregory (2009); Davis et al. (2020); Dysart-Gale (2010); Falk-Rafael (2005); Falk-Rafael and Betker (2012); Kirkham and Browne (2006); Kirkham, Van Hofwegen, and Hoe Harwood (2005); Lind and Smith (2008); MacKinnon and Moffitt (2014); Nemetchek (2019); Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter (2015) | 15 |

| Iran | Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan (2021); Hosseinzadegan, Jasemi, and Habibzadeh (2021); Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi, and Javaheri Tehrani (2022) | 3 |

| United Kingdom | Abu (2022); Cuthill (2016); Scheffer et al. (2019) | 3 |

| New Zealand | Giddings (2005) | 1 |

| South Africa | Macleod and Nhamo-Murire (2016) | 1 |

| Pakistan | Shahzad et al. (2022) | 1 |

| Israel | Nissanholtz–Gannot and Shapiro (2021) | 1 |

| Turkey | Nesime and Belgin (2022) | 1 |

| Zambia | Thuma-McDermond (2011) | 1 |

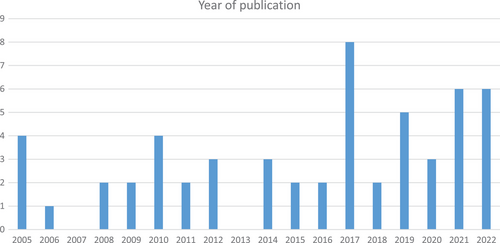

The year of publication of the included studies ranged from 2005 to 2022. A total of 69% of the included sources included were published in 2014 or later (Table 4 and Figure 2).

| Year published | Studies |

|---|---|

| 2005 | Bekemeier and Butterfield (2005); Falk-Rafael (2005); Giddings (2005); Kirkham, Van Hofwegen, and Hoe Harwood (2005) |

| 2006 | Kirkham and Browne (2006) |

| 2007 | |

| 2008 | Browne and Tarlier (2008); Lind and Smith (2008) |

| 2009 | Anderson et al. (2009); Cohen and Gregory (2009) |

| 2010 | Clingerman and Fowles (2010); Dysart-Gale (2010); Kagan et al. (2010); Logsdon and Davis (2010) |

| 2011 | Groh et al. (2011); Thuma-McDermond (2011) |

| 2012 | Grace and Willis (2012); Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo (2012); Falk-Rafael and Betker (2012) |

| 2013 | |

| 2014 | MacKinnon and Moffitt (2014); Ray and Turkel (2014); Thompson (2014) |

| 2015 | Yanicki et al. (2015); Caldwell and Watterberg (2015) |

| 2016 | Cuthill (2016); Macleod and Nhamo-Murire (2016) |

| 2017 | Bell (2017); LeBlanc (2017); Perry et al. (2017); Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe (2017); Valderama-Wallace (2017); Walter (2017); Matwick and Woodgate (2017); Shearer (2017); Perry et al. (2017) |

| 2018 | Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe (2018); Hellman et al. (2018) |

| 2019 | Mooney-Doyle, Keim-Malpass, and Lindley (2019); Nemetchek (2019); Scheffer et al. (2019); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2019) |

| 2020 | Davis et al. (2020); Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano (2020); Boutain (2020) |

| 2021 | Elliott and Sandberg (2021); Garcia (2021); Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan (2021); Hosseinzadegan, Jasemi, and Habibzadeh (2021); Matwick, Martin, and Scruby (2021); Nissanholtz–Gannot and Shapiro (2021) |

| 2022 | Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy (2022); Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi, and Javaheri Tehrani (2022); Nesime and Belgin (2022); Shahzad et al. (2022); Velasco and Reed (2023)a; Abu (2022) |

- a This study was published online in 2022.

Most included sources were prepared within the qualitative paradigm—50 in total. Two were mixed methods studies, and three were quantitative studies. The three quantitative studies were RCTs (Nesime and Belgin 2022) or used questionnaires (Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels 2011; Scheffer et al. 2019) as their methods. One study (Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy 2022) used mixed methods and analyzed questionnaires and written reflections. Another study (Ray and Turkel 2014) presented a theory of relational caring complexity derived from previous qualitative and quantitative research by the authors. The most used methodologies were critical grounded theory (Abu 2022; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019, 2020; Walter 2017) and theory/concept analysis inspired by Walker and Avant (Garcia 2021; Matwick and Woodgate 2017; Nemetchek 2019; Shearer 2017; Velasco and Reed 2023). Interviews, focus groups, and literature reviews were the most frequently used data collection methods. Almost a third of the studies were theoretical research reviewing, examining, or analyzing a topic with a social justice or theoretical lens.

3.1.2 Definition of Social Justice

Only a few of the included studies adopted a specific definition of social justice. Some studies used the concept of social justice without explaining what was meant or how the concept was understood. However, many studies discussed numerous definitions and understandings of social justice, albeit not adhering to one in particular. Many theories and philosophies were mentioned to have added to the current conceptualization and understanding of social justice, including feminist theory, critical theory, post-colonial theory, American pragmatism, (neo)Marxism, and queer theory. Often, social justice was conceptualized as a hybrid, combining elements from numerous theories. In some studies, social justice was linked to and conceptualized as emancipatory knowing. Emancipatory knowing was added by Chinn and Kramer (2018) to the four patterns of knowledge initially identified by Carper (1978) as a fifth and central part. Emancipatory knowing may be defined as the ability to be concerned with, critically react to, and understand the political, social, and cultural status quo (Chinn and Kramer 2018). Some studies proposed their definition of social justice through concept analysis, while others described their understanding of social justice adopted in their study. Table 5 presents various definitions and understandings used in the included studies. Some definitions and understandings are general, while others relate specifically to healthcare or nursing. “Own definition” refers to a definition developed by the authors of a study. In contrast, “own understanding” describes how a study's authors understand social justice or how it is viewed within the specific study. A “borrowed definition” refers to a set definition of social justice adopted by the authors of a study but proposed by someone else. We have limited these definitions in the below overview (Table 5) to include only definitions of social justice in healthcare, nursing, or proposed by nurses.

| Source of definition | Definition | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian Nurses Association (2005) | “Founded on the idea of fair distribution of society's benefits, responsibilities, and their consequences.” | Borrowed definition. |

| Smith, Jacobson, and Yiu (2008) | “The degree of equality of opportunity for health made available by the political, social, and economic structures and values of a society.” | Borrowed definition. |

| American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2008) | “Social justice as acting in accord with fair treatment regardless of economic status, race, ethnicity, age, citizenship, disability or sexual orientation.” (pp28) | Borrowed definition. |

| Canadian Nurses Association (2010) | Social justice is equity in society. It means the equitable, or fair, distribution of society's benefits, responsibilities, and their consequences. It focuses on the relative position of social advantage of one individual or social group in relationship to others in society, as well as on the root causes of inequities and what can be done to eliminate them. In this view, societal benefits and responsibilities are distributed so that disadvantaged populations have priority. | Borrowed definition. |

| Kagan et al. (2010) | We see social justice as incorporating all of these ideas (philosophic and religious traditions, critical social theory, feminist theory, Rawls, and Aquinas) within a context of the inherent worth and mutual interdependence of human beings founded on solidarity and reciprocal respect. Following Rawls, we see any process of social justice as one of breaking down barriers to access for individuals or groups possessed of particular identities, abilities, or histories, exemplifying inclusion rather than exclusion. | Own understanding. |

| Dysart-Gale (2010) | “Social justice,” is understood as the professional obligation to fight disparities in health care that result from social bias or inequity. | Own understanding. |

| Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo (2012) | Social justice was defined as full participation in society and the balancing of benefits and burdens by all citizens, resulting in equitable living and a just ordering of society. | Own definition derived from concept analysis. |

| American Nurses Association (2015) | “Nursing's professional responsibility to address unjust systems and structures.” | Borrowed definition. |

| Matwick and Woodgate (2017) | Social justice in nursing—A state of the equitable distribution of services affecting health and helping relationships. Social justice is achieved through the recognition and acknowledgment of social oppression and inequity and nurses’ caring actions toward social reform. | Own definition from concept analysis. |

| Nemetchek (2019) | “Fundamental human right to be protected, a moral obligation demonstrated by action, and results in change that improves the health of individual lives and populations both locally and globally by recognizing and confronting injustice, oppression, and inequity, while promoting participation, opportunity, justice, equity, and helping relationships” (p. 247–248). | Own definition of social justice in global health based on a concept analysis. |

| National Academies of Sciences & Medicine (2021) | Social justice: The concept that everyone deserves equal rights and opportunities. In healthcare, it refers to the delivery of high-quality care to all individuals. | Borrowed definition. |

| Matwick, Martin, and Scruby (2021) | In this framework, social justice is defined as the equitable distribution of societal benefits that affect health, with specific emphasis on the social determinants of health, caring relationships, and health equity (CNA 2021; Falk-Rafael and Betker 2012; Kirkham and Browne 2006; Matwick and Woodgate 2017). Of note, this definition highlights health equity as the goal or outcome of social justice and clarifies the relationship between the two concepts, which is often blurred or unclear (Kirkham and Browne 2006; Matwick and Woodgate 2017; Powers and Faden 2006). | Own understanding, partially derived from own previous definition based on concept analysis. |

| Elliott and Sandberg (2021) | Own definition of social justice in relation to the topic of this review: For the purposes of this literature review, teaching social justice involves helping students develop an empathetic understanding of vulnerable populations, the ability to critically analyze social determinants, and knowledge of how to advocate collaboratively to become agents for change. | Own understanding. |

Two of the three dissertations (Abu 2022; Thuma-McDermond 2011) included in this scoping review comprised long sections on the history and conceptualization of social justice. One (Thuma-McDermond 2011) settled for the definition of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. In contrast, the other (Abu 2022) offered a long and comprehensive outline of the author's understanding of the concept, which is too long to include in the above overview.

3.1.3 Themes

Five themes were identified in the 55 included sources in this scoping review. The themes were identified during the charting process and subsequently when reading through the entire data matrix. The five identified themes are education, concept, theory, public health and community nursing, and maternal and child health.

3.1.4 Education

A total of 20 sources dealt with social justice education (Abu 2022; Bell 2017; Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe 2018; Cohen and Gregory 2009; Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy 2022; Davis et al. 2020; Elliott and Sandberg 2021; Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels 2011; Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan 2021; Hellman et al. 2018; Kirkham, Van Hofwegen, and Hoe Harwood 2005; LeBlanc 2017; Nesime and Belgin 2022; Scheffer et al. 2019; Shahzad et al. 2022; Thuma-McDermond 2011; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019, 2020). Educating nursing students on social justice, poverty, disparities, advocacy, health equity, social determinants of health, and service-learning was found to increase their understanding, reflective thinking, critical thinking, and self-awareness, and to shape their professional formation and understanding of social justice as a value in nursing (Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy 2022; Elliott and Sandberg 2021; Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels 2011; Hellman et al. 2018; LeBlanc 2017; Nesime and Belgin 2022; Scheffer et al. 2019; Shahzad et al. 2022; Thuma-McDermond 2011). Teaching methods and strategies for teaching social justice and allied topics included the use of cases and stories (LeBlanc 2017; Shahzad et al. 2022), simulation (Hellman et al. 2018), clinical placements or visits (Bell 2017; Cohen and Gregory 2009; Kirkham, Van Hofwegen, and Hoe Harwood 2005; Thuma-McDermond 2011), traditional coursework (Crawford, Jacobson, and McCarthy 2022; Nesime and Belgin 2022; Scheffer et al. 2019), reflective thinking or journaling (Cohen and Gregory 2009; Hellman et al. 2018; Shahzad et al. 2022), and service-learning (Groh, Stallwood, and Daniels 2011). Several studies also advocated for an overall change in nursing education in terms of admission, pedagogy, and dealing with racism and colonialism within nursing and nursing education (Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe 2018; Davis et al. 2020; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019, 2020). Several sources emphasized that several challenges are associated with the current teaching of social justice and related topics in nursing education (Abu 2022; Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe 2018; Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan 2021; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019, 2020). A primary challenge is the understanding and competence of the nursing educators teaching the students (Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan 2021). Furthermore, several studies problematize the lack of a conceptual understanding of social justice on the part of nursing educators and its equivocal place in nursing education (Abu 2022; Habibzadeh, Jasemi, and Hosseinzadegan 2021; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019, 2020). Another challenge is the persistent focus on the individual and the nurse-patient dyad as opposed to a more structural view of health and its determinants (Blanchet-Garneau, Browne, and Varcoe 2018; Thurman and Pfitzinger-Lippe 2017). Generally, all sources addressing social justice and education advocated for education in social justice and allied topics as a way to work toward the nursing profession becoming more aware of social justice, gaining an understanding of social justice, and being competent in intervening and addressing social (in)justice.

3.1.5 Concept

The concept of social justice was defined at various depths in several of the included studies, as described in the section on definitions of social justice and Table 5. Eleven included studies; however, (Anderson et al. 2009; Bekemeier and Butterfield 2005; Boutain 2020; Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo 2012; Kirkham and Browne 2006; Matwick and Woodgate 2017; Nemetchek 2019; Thompson 2014; Valderama-Wallace 2017; Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019; Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter 2015) dealt specifically with “concept” as their central theme. These studies focused on conceptualizing social justice and the nursing discourse about social justice and allied concepts such as fairness, justice, and health equity. Several studies (Anderson et al. 2009; Kirkham and Browne 2006) proposed that a post-colonial, critical, and feminist view of social justice would allow for a deeper and broader conceptualization and understanding of social justice, its antecedents, and its consequences. Similarly, it was argued that a broad and deep conceptualization and understanding were needed for nurses to have the necessary awareness, knowledge, and competence to act on social (in)justice. A broad conceptualization considers all factors and is described in one study (Kirkham and Browne 2006) as three-dimensional, considering both redistribution, recognition, and parity of participation. One study (Valderama-Wallace and Apesoa-Varano 2019) exploring the conceptualization of social justice by nurses, nurse educators, and nursing students showed that social justice is often conceptualized as (health) equity, equality, self-awareness, withholding judgment, taking action, equitable distribution, and helping relationships. Three studies (Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo 2012; Matwick and Woodgate 2017; Nemetchek 2019) brought forth their definitions of social justice, all using concept analysis (see Table 5). One definition pertains to global health (Nemetchek 2019), one to nursing (Matwick and Woodgate 2017), and one is general (Buettner-Schmidt and Lobo 2012) (see Table 5). Three studies (Bekemeier and Butterfield 2005; Valderama-Wallace 2017; Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter 2015) examined the conceptualization of social justice in documents and were generally critical of it. One study (Bekemeier and Butterfield 2005) examined documents by the Canadian Nurses Association and found their conceptualization of social justice to be inconsistent, ambiguous, and superficial. One review (Boutain 2020) of nursing literature from 2000 to 2018 found that social justice was conceptualized without a complex and coherent understanding of the concept.

3.1.6 Theory

Eight studies (Abu 2022; Falk-Rafael 2005; Matwick, Martin, and Scruby 2021; Perry et al. 2017; Ray and Turkel 2014; Shearer 2017; Walter 2017; Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter 2015) included in this scoping review developed a theory, model, or framework, regarding social justice and nursing. Three of these studies (Perry et al. 2017; Ray and Turkel 2014; Walter 2017) proposed a general model or theory for nursing. In one study (Walter 2017), a theory of emancipatory nursing praxis was constructed using constructivist grounded theory. In another study (Perry et al. 2017), a model of nursing essential freedom was developed to facilitate humanizing social justice action. In another study (Ray and Turkel 2014), a theory of relational caring complexity, developed from the previous work of the authors, was presented. The theory offers insights into caring as an emancipatory praxis within the healthcare system described as highly medicalized and bureaucratic. One study (Yanicki, Kushner, and Reutter 2015) was distinctly rooted in a Canadian context, but it proposed that the integrated framework developed may interest nurses beyond Canada. The study developed an integrated framework for social justice incorporating discourses on recognition, capabilities and equality, and citizenship. Two studies (Falk-Rafael 2005; Matwick, Martin, and Scruby 2021) focused on theories for public health nursing. One study (Falk-Rafael 2005) proposed a midrange theory of critical caring for public health nursing practice. This study merged Watson's caring science with critical feminist theories to develop a novel theory. The other study (Matwick, Martin, and Scruby 2021) developed a framework to equip nurse leaders and public health nurses with concepts to help them identify and develop the needed support for nurses to integrate social justice praxis with public health nursing. One study (Shearer 2017) developed a critical caring theory of protection for migrants and seasonal farmworkers using environmental health research frameworks, critical caring theory, and empirical evidence. In a PhD dissertation (Abu 2022), situated in critical interpretivism and constructivist grounded theory, a framework on awareness for social justice action for nursing education was developed to foster critical nursing students who are aware of and can take action in relation to social justice.

3.1.7 Public Health and Community Nursing

Seven studies (Cohen and Gregory 2009; Falk-Rafael 2005; Falk-Rafael and Betker 2012; Lind and Smith 2008; MacKinnon and Moffitt 2014; Matwick, Martin, and Scruby 2021; Nissanholtz–Gannot and Shapiro 2021) included in this scoping review touched in various ways on the topic of public health and/or community nursing. One study (Falk-Rafael 2005) proposed a midrange theory of critical caring for public health nursing, potentially rooting current public health nursing in the social justice agenda of early public health nursing practice. Another study (Falk-Rafael and Betker 2012) interviewed community health nurses concerning their daily practice and analyzed their responses in light of critical caring theory; a combination of Watson's caring science, feminist critical theory, and the legacy of Nightingale's social activism. The study found congruence between the theory and public health nursing practice but also found that public health nurses encounter many barriers in their practice. Another study (Nissanholtz–Gannot and Shapiro 2021) on the roles of community nurses in chronic disease management in Israel found that community nursing practice has expanded in Israel. However, conflicts with doctors occur and potentially limit nurses' contribution toward reducing health inequalities. Yet another study (Matwick, Martin, and Scruby 2021) developed a framework to support public health nurses in integrating social justice praxis within public health nursing. The study revealed a need for a shared vision of social justice, autonomy, shared decision-making, opportunities for learning, and sufficient resources in collaboration with community partnerships. One study (Lind and Smith 2008) used appreciative inquiry with adolescents and high-school staff to move from a deficit- to strength-based practice. Another study (MacKinnon and Moffitt 2014) examined informed advocacy and found that this helps nurses contribute to improving the health of people living in rural and remote areas. A study (Cohen and Gregory 2009) identified enabling factors and challenges for developing the community health nursing role in nursing education. The study found that exposure to concepts such as social determinants of health and social justice was essential to develop the community nursing role, along with an innovative setting, sufficient supervision, and an opportunity to engage in critical reflective thinking.

3.1.8 Maternal and Child Health

Six studies (Caldwell and Watterberg 2015; Clingerman and Fowles 2010; Garcia 2021; Grace and Willis 2012; Logsdon and Davis 2010; Mooney-Doyle, Keim-Malpass, and Lindley 2019) focused on maternal and/or child health and social justice. One study (Garcia 2021) used the middle-range theory of emancipatory nursing practice as a framework to study obstetric violence. Two studies (Clingerman and Fowles 2010; Logsdon and Davis 2010) focused on maternal and infant care and the role of nurses in ensuring health equity and social justice. One study (Grace and Willis 2012) presented Powers and Faden's framework for social justice, analyzed its six interrelated dimensions, and applied them to the issue of child abuse. One study (Mooney-Doyle, Keim-Malpass, and Lindley 2019) analyzed concurrent care for children from a social justice perspective. The five mentioned studies were all theoretical in nature. They used theory to analyze maternal and child health and then derived implications for practice, education, policy, and further research. The sixth study focused on child and maternal health and was different from the other five. It evaluated swaddling as an adjunct pain and stress control method during endotracheal intubation from an emancipatory and social justice rationale/perspective (Caldwell and Watterberg 2015).

3.1.9 Studies Outside Themes

Six of the 55 studies in this scoping review did not fit into the five identified themes. Two studies (Hosseinzadegan, Jasemi, and Habibzadeh 2021; Rafii, Nikbakht Nasrabadi, and Javaheri Tehrani 2022), both from Iran, identified factors that are involved in and determine praxis in nursing and nurses' participation in establishing social justice in healthcare. One study (Giddings 2005) collected stories of difference and fairness within nursing from nurses in the United States and New Zealand, finding that old ideological constructions and taken-for-granted ideals fuel the marginalization of those deemed not to fit in nursing. One study (Dysart-Gale 2010) examined the social and health-related experiences of LGBTIQ youth in Canada. It argued that the social justice position of nurses positions nurses to intervene and promote the well-being of LBGTIQ+ youth. Another study (Macleod and Nhamo-Murire 2016) reviewed research on nursing practice concerning sexuality from an emancipatory/social justice perspective and found that nurses’ social location and their personal feelings regarding sexuality influenced their practice. One study (Browne and Tarlier 2008) examined nurse practitioners’ potential from a critical social justice perspective and found that a critical social justice perspective is essential for nurse practitioners to achieve health equity.

4 Discussion

This scoping review examined the current extent, range, and nature of nursing and social justice research. A total of 55 studies were included and summarized regarding study characteristics, definition of social justice, and themes.

4.1 Study Characteristics

The consolidation of studies revealed that the included studies mainly relied on qualitative methods, were primarily published in a handful of journals, and had been published from 2014 onward. We also showed that most studies were published by authors from the United States and Canada. In contrast, no studies from continental Europe, South America, or Asia were identified, and only one study originated from Africa. The journals that had published the 55 studies were also overwhelmingly founded, printed, or affiliated with organizations in North America. This skewed geographical distribution may have several causes. A recent scoping review showed that slightly less than 85% of all identified studies examining policy advocacy conducted by nursing organizations pertained to North American nursing organizations (Chiu et al. 2021). A strong emphasis on advocacy may exist within the nursing profession in North America, which could be associated with its diverse population, history, and considerable health disparities. However, speculating on this falls beyond this scoping review but may be worth investigating in a separate study.

4.2 Definition of Social Justice

Several included studies focused specifically on concept and conceptualization, and many more explored and discussed the conceptualization of social justice in their introductions or discussions. While some studies developed their definition or understanding of social justice, many others relied on definitions from other authors or institutions. While the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) have received a fair share of criticism in nursing research for lack of consistency, clarity, and guidance on social justice in their documents, the sheer number of references made to their definition and writings on social justice testify to their role and position within nursing. It is also worth noting that the ANA, the CNA, and the New Zealand Nurses Organization have been forerunners in explicitly focusing on social justice. While many studies clearly and extensively discussed and explained their understanding and/or conceptualization of social justice, others did not address this subject. Numerous included studies did not describe what social justice meant in their work. Some even investigated using a social justice lens without explaining what such a lens entails. Currently, no shared definition exists of social justice in nursing. As with most concepts, a shared definition may never be achieved and possibly should not be. It is, however, clear that considerable interest is being devoted to exploring and discussing the conceptualization of social justice in nursing. It is also evident looking at the evolving understanding of social justice through time that recognition is growing to the fact that social justice extends beyond distributive justice to encompass elements such as acknowledgment and participation.

4.3 Themes

Given the current interest in and state of research on social justice in nursing, it is perhaps not unnatural that concept, theory, and education take up much of the knowledge base. If nurses are to be sensitized and educated to act and intervene on social justice issues, we must start by developing a sense of the concept, educating nurses on the topic, and developing theory to guide practice. As the knowledge base on social justice in nursing research and nursing generally grows and matures, one might speculate that we will see more studies move toward exploring practice and specific population groups. In this scoping review, very few studies focused on specific population groups or clinical specialties. Besides maternal and child health and public health and community nursing, the only specific population groups given particular focus in the included studies were migrants and asylum-seekers (11, 43), LGBT adolescents (13), and transgender and gender-diverse individuals (55).

4.4 Limitations

To our knowledge, this scoping review is the first on social justice and nursing. We introduced no limitations on the year of publication or research design, thereby presenting a complete overview of the current knowledge base. However, this scoping review is not without limitations.

The limitations are primarily associated with the set eligibility criteria. First, this scoping review investigated the concept of social justice, not the phenomena of social justice. Had we investigated the phenomena of social justice, words referring to or covering this phenomenon besides the phrase “social justice” should have been included in the search strategy. Words that border on or (partly) cover the phenomenon of social justice include, for example, justice, social change, health equity, emancipatory, and social determinants of health. Other relevant words include action, engaging, or critical thinking. Second, we set nursing as the context and excluded all sources not specifically related to nursing. However, determining when something has nursing as its context proved more difficult than expected. Nursing as a profession covers an extensive range of activities, specialties, and areas of interest. Additionally, one might ask if research conducted by nurses necessarily falls within nursing? We needed to establish where nursing starts and ends. Ultimately, in scoping reviews, as with all reviews, one must draw a line between what is included and what is not. We therefore decided that the context must be specifically and clearly stated to relate to nurses and nursing. Third, when revising the selection process, we realized that we needed to critically examine how we, as the author team, defined and recognized research. We had to look inward and acknowledge that we are influenced by quantitative and medical paradigms of what constitutes real science. This prompted critical reflection among us, as an author group, regarding the nature of theoretical research. When do essay or discussion-style papers reach a depth of analysis that may be labeled theoretical research? Many articles that were not empirical had little explanation or description of their method, inquiry, or conduct. This occasionally made it difficult to distinguish whether the research was theoretical. Ultimately, it was up to us as the author team to determine whether each work was to be considered theoretical research, which inevitably means that some studies could have been wrongfully omitted or included. In addition to the limitations related to the eligibility criteria, no formal appraisal was made of the included studies; this is consistent with other scoping reviews (Peters et al. 2020). However, notes on quality were taken when reading through and charting the studies. These notes revealed that some of the included studies lacked a transparent and thorough description of design, methods, and mode of inquiry. Several studies, for example, claimed to use a social justice lens for analysis without explaining what such a lens might entail or consist of. Many studies went to great lengths to clearly describe or signpost allegiance to or influence from formal theory, philosophy, or scientific theory. In contrast, others, even qualitative studies, failed even to mention their theoretical backdrop.

5 Conclusion and Implication for Practice and Research

In conclusion, this scoping review showed that nursing research on the concept of social justice is primarily limited in its geographical range to English-speaking countries. Here, the interest in social justice is growing. Most studies on social justice and nursing focus on concept, theory, and education; and these studies focus on nursing in general and do not explore specific specialties or groups. Public health, community nursing, and maternal and child health are the exceptions that confirm this rule. Many studies on social justice and nursing are qualitative and/or theoretical in nature. Data collection in empirical studies uses mostly interviews and focus groups. Studies on social justice and nursing define social justice by their own developed definition, borrowing a definition or explaining their understanding of the concept. Many philosophies and theories have influenced the conceptualization of social justice, most of which go beyond notions of distributive justice and incorporate recognition and participation. Some studies fail to explicitly define what they mean by social justice, and some lack clear and precise aims and/or descriptions of the method, design, or mode of inquiry used.

More research is needed on social justice and nursing. Future research would benefit from taking on upstream, midstream, and downstream perspectives. Upstream by exploring how structural determinants such as exclusion, racism, marginalization, and social status affect patients' health, well-being, and the context, delivery, and allocation of nursing care; midstream by exploring the intermediary determinants such as housing, transport, and food security through a social justice lens and investigating how these aspects influence patients' health and well-being and the provision of nursing care; downstream by studying patients’ immediate needs and nurses' daily practice in a social justice perspective. Future research on social justice may identify implications and propose strategies for all practices in tackling health inequity and social injustice at every level. This process starts with sensitization and reflection—and by opting to take up the mantel of social justice.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank research librarians Anne-Marie Fiala Carlsen and Marie Lundsfryd Nielsen for their assistance.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.