Food Insecurity in Pediatric Kidney Transplant Recipients

ABSTRACT

Background

Food insecurity (FI) has documented negative health impacts on children, with a higher prevalence in children with kidney disease. The prevalence and consequences of FI in pediatric kidney transplant recipients are unknown.

Methods

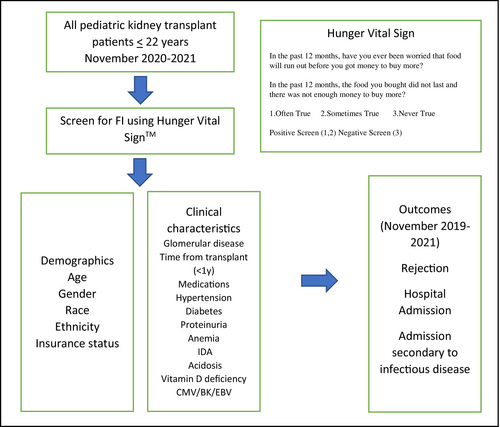

In this study, we screened and assessed pediatric kidney transplant recipients for FI using the Hunger Vital Sign and analyzed the impact of FI on pediatric kidney transplant outcomes.

Results

Of the 118 pediatric kidney transplant recipients screened, 23 (19.5%) were identified as FI. Food-secure and food-insecure recipients were not significantly different in age or gender, but there was significantly more FI in recipients of Hispanic ethnicity (56% vs. 30%) and with public insurance (83% vs. 52%). Markers of nutrient stores and transplant outcomes were not significantly different in recipients with FI.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the feasibility and importance of screening pediatric kidney transplant recipients for FI with the Hunger Vital. The observed link of FI with demographic characteristics such as Hispanic ethnicity and having public insurance offers potential targets for intervention. Larger studies assessing FI and outcomes in pediatric transplant recipients are critical for focused interventions and policy development.

1 Background

Food insecurity (FI), defined by USDA as inconsistent access to food or worry over food shortage that prevents an active, healthy life [1], is prevalent in 10%–15% of all American households [2, 3]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, unfortunately, FI increased to 20% [3]. The impact of FI on health outcomes in the general pediatric population includes but are not limited to delayed presentation to medical care, increased emergency department visits and hospitalizations, higher incidence of chronic disease, and poorer academic performance [4-10].

The prevalence of FI is even higher in children with kidney disease, with reports as high as 35% in general nephrology clinics and 64% in dialysis clinics [11], although the impact of the pandemic on prevalence in this population is unknown. FI is also associated with higher rates of hospitalization for children on dialysis. Despite recent reports in FI on the general pediatric nephrology and dialysis population [11, 12], the prevalence and consequences of FI in pediatric kidney transplant recipients are unknown.

In this study, we screened and assessed pediatric kidney transplant recipients for FI. We hypothesized that there would be an increased prevalence of FI in our outpatient kidney transplant patients compared to the current rates for the general population. In addition, we assessed the impact on transplant outcomes to test our hypothesis that increased FI would be associated with higher rates of transplant rejection, hospital admissions, and admissions secondary to infections.

2 Methods

We performed a single center cross-sectional pilot study of all kidney transplant recipients at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago. All kidney transplant recipients under 22 years of age seen in clinic from November 2020 to November 2021 who had a completed FI screen using The Hunger Vital Sign [13] were included. The tool was administered to the caregivers (if recipients < 18 years of age) and recipients (if > 18 years of age) by the transplant nurses at the time of clinic rooming and entered into the electronic medical record for documentation. Patients were identified as FI if they answered affirmatively to either question in The Hunger Vital Sign (Figure 1).

Demographic, disease characteristics, clinical characteristics, and markers of nutrient stores were compared across FI status. Our primary outcome of interest was biopsy-proven transplant rejection and hospitalization in pediatric kidney transplant recipients in the year preceding and following being identified as food insecure, including infectious-related hospitalizations.

Deidentified data was analyzed using STATA 11.0. Categorical values were assessed via chi-squared testing and continuous via T test. Transplant rejection episodes, hospital admissions, and infectious admissions were analyzed using chi-squared testing, with a significance level of 0.05. This study was considered exempt from the institutional review board at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital in Chicago.

3 Results

Of the 145 transplant recipients that were seen in the Pediatric Kidney Transplant Clinic during the study period, 118 were screened with the Hunger Vital Sign [6] tool and were included. Of these, 23 (19.5%) identified as FI. Food secure and insecure recipients were not significantly different in age or gender, but there were significantly more FI recipients of Hispanic ethnicity (56% vs. 30%). FI was significantly more likely in recipients with public insurance (83% vs. 52%). FI recipients were more likely to have glomerular disease, albeit not a significant difference (52% vs. 33%, p = 0.081). Thirty-seven percent of the study population were within the first year of kidney transplant and were evenly distributed between FI and food secure cohorts (Table 1).

| Variable N (%) | Food Insecure N = 23 (19%) | Food Secure N = 95 (81%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Age in years (mean + SD) | 13 ± 5 | 13 ± 6 | 0.882 |

| Female sex | 11 (48%) | 35 (37%) | 0.332 |

| BMI (mean + SD) | 21 ± 5 | 21 ± 6 | 0.900 |

| Race | |||

| White | 18 (78%) | 80 (84%) | 0.514 |

| Black | 2 (9%) | 9 (10%) | |

| Asian | 3 (13%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 13 (56%) | 28 (30%) | 0.015 |

| Public Insurance | 19 (83%) | 49 (52%) | 0.007 |

| Disease/Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Glomerular disease | 12 (52%) | 31 (33%) | 0.081 |

| Within first year of transplant | 10 (43%) | 34 (36%) | 0.494 |

| Number of immunosuppressive drugs (mean + SD) | 3.08 ± 0.9 | 2.95 ± 1.02 | 0.550 |

| Hypertension | 22 (96%) | 83 (87%) | 0.255 |

| Diabetes | 1 (4%) | 9 (10%) | 0.428 |

| Proteinuria | 8 (35) | 40 (42) | 0.521 |

| Anemia | 18 (78) | 72 (76) | 0.803 |

| Iron deficiency Anemia | 13 (57) | 43 (45) | 0.332 |

| Acidosis | 20 (87) | 79 (83) | 0.657 |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 16 (70) | 55 (58) | 0.305 |

| Any Cytomegaloviremia | 2 (9) | 21 (22) | 0.145 |

| Any BK viremia | 1 (4) | 5 (5) | 0.858 |

| Transplant outcomes | Relative risk (95th %ile CI) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejection episodes | 4 (17%) | 18 (19%) | 0.92 (0.34–2.45) | 0.864 |

| Any Hospital Admissions | 16 (70%) | 58 (61%) | 1.14 (0.83–1.56) | 0.437 |

| Any Admissions for Infectionb | 11 (48%) | 37 (39%) | 1.23 (0.75–2.02) | 0.449 |

- a Transplant outcomes were assessed within the year prior to and after food security screening.

- b Reason for Admission was confirmed to be infection based on Primary Discharge Diagnosis.

Markers of nutrient stores, namely anemia, iron deficiency, acidosis, and vitamin D deficiency were not significantly different across FI status. Other variables assessed, including posttransplant diabetes (p = 0.4), hypertension (p = 0.3), and the number of immunosuppressive medications (a surrogate for burden of disease) (p = 0.5) were not significantly different across FI status. (Table 1).

The incidence of biopsy proven rejection was not significantly different across FI status, occurring in 17% and 19% of FI and food secure respectively (p = 0.8). The admission for any cause was high in our cohort, but similar across both groups. Notably, the study period is during the COVID-19 pandemic, where the trigger for admission was initially high for all suspected infections in immunosuppressed patients. Infection related admissions (suspected or confirmed infection) were equal across both groups (Table 1).

4 Discussion

Our study demonstrates a 20% prevalence of FI status in pediatric kidney transplant patients in a tertiary care center in Chicago, IL, USA during the COVID-19 pandemic with significant overrepresentation in patients with public insurance. Public insurance may be a surrogate marker for poverty with an intuitive association with FI, as in previous studies, and suggests inadequate financial protection in the setting of illness. Contrary to studies assessing associations of FI and clinical outcomes in pediatric dialysis patients [11], our study focused on pediatric transplant recipients and found no association of FI and rejection or hospitalizations.

Our study found a higher prevalence of FI amongst those of Hispanic ethnicity. The vulnerability of Hispanic children is well known, with reported rates of FI as high as 33% [14]. While the immigration status of our patients or their families is unknown, children of immigrant Hispanic parents are more likely to be FI [15]. Chicago likely has an overrepresentation of this population based on census data from 2021: 20.4% of the population in Chicago is foreign born, and of these, the majority (51.8%) come from Spanish-speaking countries. In addition, our hospital is a tertiary care facility and ~ 42% of our center's patient population is Hispanic. Given that 56% of recipients with FI were of Hispanic ethnicity, the observed better transplant outcomes in Hispanic kidney recipients [16, 17], plausibly due to their strong social support systems [18, 19], may have mitigated the negative impact of FI on transplant outcomes. Since our cohort includes only two Black patients, the association of FI and outcomes for this patient population could not be adequately assessed.

5 Limitations

Beyond the obvious small sample size, nonrespondents, and lack of longitudinal data limit the ability to capture significant associations. Additionally, our data collection was during the pandemic, limiting generalizability.

6 Conclusion

Our study highlights that the Hunger Vital Sign [13] tool is feasible and important for screening pediatric kidney transplant recipients for FI. It emphasizes the high prevalence of FI in pediatric kidney recipients and supports the routine implementation for all pediatric kidney recipients. Our study findings link certain demographic characteristics such as Hispanic ethnicity and having public insurance with FI, which offers potential targets for intervention. Larger studies assessing FI and outcomes in pediatric transplant recipients are critical for focused interventions and policy development.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.