Discordance Between Caregiver and Transplant Clinician Priorities Regarding Post-Heart Transplant Education

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Patient and caregiver education following pediatric heart transplant (HTx) is a cornerstone of post-HTx care. Despite the importance of post-HTx education, there are no standardized guidelines for topics and content. Education practices vary across clinicians and centers. Patient and caregiver priorities regarding post-HTx education are unknown. This national survey study aimed to characterize adolescent HTx recipient, caregiver, and clinician values specific to post-HTx educational topics.

Methods

A cross-sectional, national electronic survey was performed. Eligible participants included pediatric HTx recipients between the ages of 13–18, adult caregivers of pediatric HTx recipients, and pediatric HTx clinicians. An investigator-designed survey was developed to assess the importance of 20 educational topics. Average scores on educational topics were compared between HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians using two-sample t-tests.

Results

120 survey responses were included, with a majority completed by HTx caregivers (N = 73; 61%) and clinicians (N = 43; 36%). Of the 20 educational topics assessed, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between educational values of HTx recipients/caregivers compared to HTx clinicians for 40% (N = 8) of the topics. For each educational topic that revealed a significant difference, HTx recipients/caregivers consistently placed greater value on the educational topic compared to HTx clinicians.

Conclusions

Priorities regarding post-HTx education do not always align between HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians. Results suggest that HTx recipients/caregivers place higher value on educational topics regarding daily life after HTx compared to HTx clinicians. We hope these findings better inform the approach to post-HTx education and care for future pediatric HTx patients.

Abbreviations

-

- APP

-

- advanced practice provider

-

- CHD

-

- congenital heart disease

-

- HTx

-

- heart transplant

-

- RN

-

- registered nurse

1 Introduction

Heart transplant (HTx) is the definitive therapy for many pediatric patients with congenital or acquired heart disease that results in end-stage heart failure. Despite advancements in HTx medical management, allograft survival remains limited [1] and HTx is associated with 9%–14% 1-year and 22%–29% 5-year mortality rates even when performed at high-volume transplant centers [1, 2]. Graft failure is the most common cause of death throughout the entire post-HTx period [3]. As such, it is critical to recognize immunosuppression non-adherence as a modifiable risk factor that leads to pediatric HTx patient death. Across solid organ transplant groups, extensive research has demonstrated that medication non-adherence leads to irreversible reduction or failure of graft function [4-7]. It has been estimated that at least 30% of pediatric solid organ transplant recipients are non-adherent to their post-transplant medication regimen [8]. Among HTx patients only, national registry data have revealed that up to 10% of patients develop medication non-adherence associated with clinical compromise at a median of 2 years after HTx [9]. Among patients with 2 or more reports of non-adherence, 56% died within 2 years [9].

Although the cause is likely multifactorial, studies have linked medication non-adherence to patients' knowledge deficits regarding their immunosuppression regimen and/or their own disease process [4, 10, 11]. Others have demonstrated that pediatric transplant patients with psychologic comorbidities such as generalized anxiety disorder or depression, as well as those who express low self-esteem, exhibit emotional and/or behavioral problems, or experience post-traumatic stress symptoms are at greater risk for medication non-adherence [4, 8, 9, 12].

To educate families on the importance of adherence to their medication regimen, as well as other critical components of self-care after transplant, HTx educational resources exist at institutional [13] and international transplant organization levels [14]. However, despite the recognized importance of patient and family education, the educational values and priorities of pediatric HTx patients and their families remain unknown. Studies in other domains of pediatric cardiology have demonstrated discrepancies in values regarding counseling for parents compared to their cardiologists [15], which highlights important opportunities for improvement in aligning caregiver and provider priorities. This first step of identifying HTx recipient and caregiver educational priorities will provide HTx interdisciplinary clinicians the opportunity to customize educational programs that are more likely to engage HTx recipients and caregivers throughout their lives after transplant.

This study aimed to: (1) characterize what post-HTx education topics are considered important to adolescent HTx recipients and adult pediatric HTx patient caregivers, compared to what is considered important to pediatric HTx clinicians, and (2) examine demographic correlates of educational priorities in HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians. It was hypothesized that there would be discordance between HTx recipient and caregiver educational priorities compared to those of HTx clinicians.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Design and Participants

This cross-sectional, national survey study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Eligible participants included adolescent HTx recipients (13–18 years old), adult caregivers of a pediatric (< 18 years old) HTx recipient, and pediatric HTx clinicians (cardiologists, advanced practice providers [APPs], and registered nurses [RNs; HTx bedside nurses and HTx nurse coordinators] actively involved in the clinical care of pediatric HTx patients).

The survey was distributed to HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians at the study center via email, after screening and participant recruitment were completed by the study team. The survey was distributed nationally to HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians through collaboration with three organizations: Pediatric Heart Transplant Society, Transplant Families, and Enduring Hearts, who helped promote and make the survey available to patients, families, and clinicians within their networks via newsletters, blogs, and social media platforms. The survey was also nationally available to HTx recipients through a private pediatric HTx recipient Facebook group. The survey was open to participants from March to August of 2023.

2.2 Measures

The investigator-designed, self-reported survey of pediatric HTx educational priorities was developed with topics selected from two sources with transplant education materials: the C.S. Mott Congenital Heart Center Resources for Congenital Heart Patients website and the Pediatric Heart Transplant Society website [13, 14]. Participants scored 20 independent educational topics on a linear 1- to 10-point ranking scale (least important to most important) across the following four domains: (1) routine medical care after heart transplant, (2) medications–familiarity and understanding, (3) complications after heart transplant, and (4) physical and psychosocial topics. Any number of independent educational topics could receive the same score throughout the survey. A comprehensive list of 30 educational topics covered by the two previously mentioned transplant education sources was identified by the principal investigator. Topics were then narrowed down from 30 to 20 total topics with the intent to optimize engagement in survey completion while maintaining a comprehensive overview of the educational material. Final topics were determined by a multidisciplinary research team composed of various pediatric HTx clinicians, which included cardiologists, APP's, psychologists, and nurse coordinators.

Surveys administered to both HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians also included demographic information for secondary assessment of participant characteristics to identify any correlations between participant characteristics and education topic priorities. The HTx recipients/caregivers sociodemographic survey initially included 11 self-reported questions. Two questions from the HTx recipients/caregivers survey (number of adult caregivers and total number of people in the home) and two questions from the caregiver only survey (gender, which matched reported “caregiver relationship to patient,” and age of caregiver) were later removed and not included within the results, as they were not felt to provide substantive data. Surveys administered only to patient caregivers included 9 demographic questions to be filled out on behalf of the patient. The HTx clinician demographic survey included 7 self-reported questions. Surveys were administered using Qualtrics survey software (Provo, UT).

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were reported as frequency and percentage for categorical variables and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. Each educational topic with a ranking scale was summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared between HTx recipients/caregivers and HTx clinicians using a two-sample t-test. As a subgroup analysis, average scores on educational topics by different HTx clinicians (physicians vs. APPs vs. RNs) were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Similarly, differences in average scores on educational topics by demographic characteristics in the HTx recipients/caregivers were examined using a two-sample t-test and ANOVA for categorical variables and the Spearman correlation coefficient for continuous variables, as appropriate. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Due to the small sample of HTx recipient responses (n = 4), a sensitivity analysis was performed following initial analyses with the removal of responses from the 4 HTx recipients. The sensitivity analysis, as detailed in Table 2, revealed nearly no changes in the initial results. The only significant difference noted in the sensitivity analysis, which includes caregiver responses only, was a relative increase in value placed on the topic “School performance and potential academic considerations after transplant,” with an original p = 0.054 increasing to p = 0.02 when excluding HTx recipient responses.

3 Results

3.1 Participants

A total of 120 survey responses were included in the analysis. The majority of surveys were completed by HTx caregivers (n = 73; 61%) and HTx clinicians (n = 43; 36%), with only 4 surveys (3%) completed by HTx recipients themselves. Respondent characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Considering HTx caregiver respondents, the majority of surveys were completed by a maternal caregiver (n = 66; 90%). The majority of caregiver respondents identified as White (n = 66; 90%), married (n = 62; 85%), and with full-time employment (n = 38; 52%). The majority of caregiver respondents were college graduates (n = 32; 44%) and reported a household income > $100 000 (n = 29; 40%). There was a fairly even distribution of responses from physicians (n = 17; 40%), APPs (n = 13; 30%), and RNs (n = 13; 30%). The majority of HTx clinician respondents identified as female (n = 34; 79%) and White (n = 32; 74%), play a primary role in providing post-HTx education (n = 37; 86%), and have practiced medicine for either 10–20 (n = 21; 49%) or > 20 years (n = 18; 42%).

| HTx recipient characteristics: completed by HTx recipients or caregivers | N = 77 |

|---|---|

| Age at survey, years (N = 75) | 13 (6–16) |

| Time since HTx, years (N = 75) | 3 (1–8) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 40 (51.9) |

| Female | 36 (45.8) |

| Non-binary | 1 (1.3) |

| Caucasian race | 65 (84.4) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 5 (6.5) |

| Pre-transplant diagnosis | |

| Congenital heart disease | 47 (61.0) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 27 (35.1) |

| Not sure | 3 (3.9) |

| Age at HTx, years (N = 75) | 3 (1–13) |

| Had a second HTx | 8 (10.4) |

| Age at second HTx, years (N = 8) | 13.5 (10.5–17) |

| HTx Caregiver characteristics: completed by caregivers | N = 73 |

|---|---|

| Caregiver relationship to HTx recipient | |

| Mother | 66 (90.4) |

| Father | 5 (6.8) |

| Grandparent | 2 (2.7) |

| Caregiver race: Caucasian | 66 (90.4) |

| Caregiver ethnicity: Hispanic | 3 (4.1) |

| Caregiver marital status | |

| Married | 62 (84.9) |

| Single | 5 (6.8) |

| Divorced | 2 (2.7) |

| Widowed | 4 (5.5) |

| Caregiver employment status | |

| Full-time employed | 38 (52.1) |

| Part-time employed | 13 (17.8) |

| Unemployed | 18 (24.7) |

| Student | 1 (1.4) |

| Retired | 2 (2.7) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.4) |

| Caregiver highest level of education | |

| High school graduate | 7 (9.6) |

| Some college or certification | 15 (20.5) |

| College graduate | 32 (43.8) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 19 (26.0) |

| Caregiver household income | |

| < $25 000 | 6 (8.2) |

| $25 000–$50 000 | 13 (17.8) |

| $50 000–$75 000 | 11 (15.1) |

| $75 000–$100 000 | 13 (17.8) |

| > $100 000 | 29 (39.7) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.4) |

| HTx provider characteristics: completed by HTx clinicians | N = 43 |

|---|---|

| Provider position | |

| Heart transplant physician | 17 (39.5) |

| Advanced practitioner (APP) | 13 (30.2) |

| Registered nurse | 13 (30.2) |

| Provider gender | |

| Male | 9 (20.9) |

| Female | 34 (79.1) |

| Provider race: Caucasian | 32 (74.4) |

| Provider ethnicity: Hispanic | 2 (4.7) |

| Primary role in providing post-transplant education | 37 (86.0) |

| Provider years of medical practice | |

| 1–5 years | 1 (2.3) |

| 5–10 years | 3 (7.0) |

| 10–20 years | 21 (48.8) |

| 20 years or more | 18 (41.9) |

- Note: Data are presented as N (%) for categorical variables and Median (interquartile range) for continuous variable.

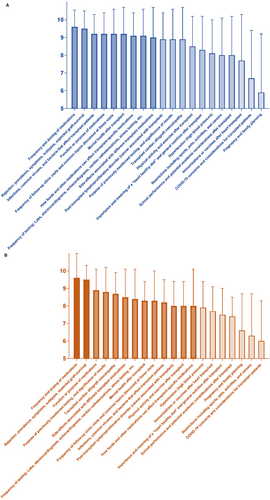

3.2 HTx Recipient and Caregiver Reported Educational Priorities

HTx recipients and caregivers placed the highest value on “Frequency and dosing of medications” (mean 9.6 ± SD 0.95), followed by “Rejection: prevalence, symptoms, subtypes, expected graft survival” (9.5 ± 1.0) (Figure 1A). Topics that shared the next highest value among patients and caregivers were “Frequency of follow-up clinic visits and common topics discussed at these visits” (9.2 ± 1.4), “Function or purpose of medications” (9.2 ± 1.2), “Infections, common viruses, and bacteria that affect transplant patients” (9.2 ± 1.1), and “Mental health after transplant” (9.2 ± 1.5). HTx recipients and caregivers placed the least value on “Pregnancy and family planning” (5.9 ± 3.3), followed by “COVID-19 concerns and considerations for transplant patients” (6.7 ± 2.7).

3.3 HTx Clinician Reported Education Priorities

HTx clinicians placed the highest value on “Frequency and dosing of medications” (9.6 ± 1.4), followed by “Rejection: prevalence, symptoms, subtypes, expected graft survival” (9.5 ± 0.81), followed by “Function or purpose of medications”(8.9 ± 1.2) (Figure 1B). HTx clinicians placed the least value on “COVID-19 concerns and considerations for transplant patients” (6.0 ± 2.3), followed by “Restrictions including sports, pets, activities, and careers” (6.3 ± 2.4).

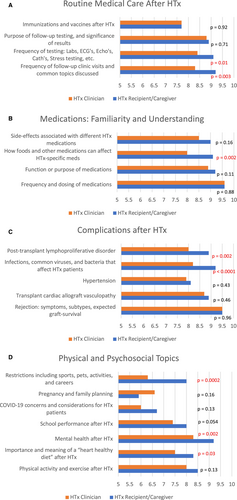

3.4 Discrepancies in Reported Education Priorities

Of the 20 educational topics assessed, there was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between educational values of HTx recipients/caregivers compared to HTx clinicians for 40% (n = 8) of the topics (Figure 2). Topics that revealed the most significant differences in educational values were “Infections, common viruses, and bacteria that affect transplant patients” (9.2 ± 1.1 vs. 8.2 ± 1.3; p < 0.0001 for recipients/caregivers and clinicians, respectively), followed by “Restrictions including sports, pets, activities, and careers” (8.0 ± 2.1 vs. 6.3 ± 2.4; p = 0.0002 for recipients/caregivers and clinicians, respectively). Other topics that revealed significant discordance between recipients/caregivers and clinicians' educational priorities included “How foods and other medications can affect transplant-specific medications,” “Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (cancer associated with transplant),” and “Mental health after transplant” (p = 0.002 for all three topics). In general, HTx recipients and caregivers consistently assigned greater value to nearly all education topics compared to HTx clinicians.

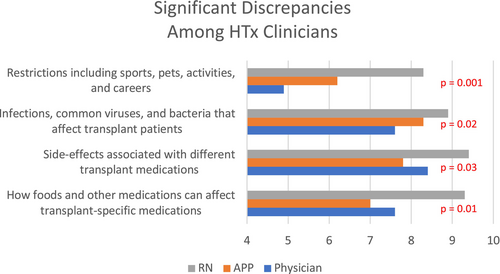

Comparing educational values assigned by different HTx clinicians, there was a significant difference in values assigned to 20% (n = 4) of topics assessed (Figure 3). The most pronounced difference in educational values assigned among HTx clinicians was “Restrictions including sports, pets, activities, and careers” (4.9 ± 2.1 vs. 6.2 ± 2.2 vs. 8.3 ± 1.4 for physicians, APPs, and RNs, respectively; p = 0.001). For each educational topic that revealed a significant difference in value assigned, RNs consistently placed greater value on the educational topic compared to HTx physicians and APPs.

Our team also assessed differences in educational values assigned by HTx recipients and caregivers based on the diagnosis of congenital versus acquired heart disease. Comparing these groups, there was a significant difference in values assigned to 10% (n = 2) of topics assessed: “School performance and potential academic considerations after transplant” (p = 0.001) and “Pregnancy and family planning” (p = 0.0003). Respondents from the acquired heart disease group rated both of these educational priorities more highly than those from the CHD group.

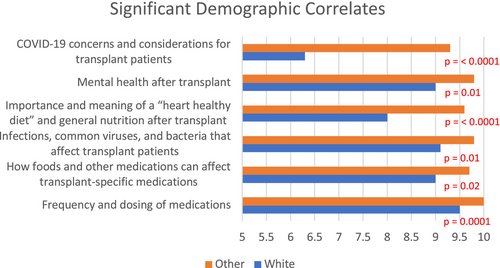

In terms of demographic correlates, the greatest number of significant differences in educational values assigned between groups was identified when comparing HTx recipients/caregivers who identified as White to those who identified as Black/African-American, Asian, or Multi-Racial. HTx recipients/caregivers who identified as Black/African-American, Asian, or Multi-Racial consistently placed greater value on the educational topic compared to those who identified as White (Figure 4). Specifically, there was a significant difference in values assigned to 30% (n = 6) of topics assessed. Topics that revealed the most significant differences in educational values between these groups were “COVID-19 concerns and considerations for transplant patients” (6.3 ± 2.6 vs. 9.3 ± 1.3; p < 0.0001 for those who identified as White, and those who identified as any other race, respectively) and “Importance and meaning of a “heart healthy diet” and general nutrition after transplant” (8.0 ± 1.9 vs. 9.6 ± 0.67; p < 0.0001 for those who identified as White, and those who identified as any other race, respectively).

4 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess post-HTx educational priorities among adolescent HTx recipients, caregivers of pediatric HTx recipients, and pediatric HTx clinicians. This study revealed that HTx recipients and caregivers place greater value on nearly all post-HTx educational topics assessed compared to clinicians, with 40% of topics revealing significant differences in values assigned. More importantly, the data suggest that HTx recipients and caregivers specifically place higher value on educational topics regarding daily life after transplant compared to clinicians.

One possible source of the discrepancy between educational values identified in this study could stem from the tangible sequelae associated with certain educational topics compared to others. For example, it is well-documented that cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV)—in addition to rejection, as previously discussed [3]—is a leading cause of death and re-transplantation in pediatric HTx patients [16-18]. This clinical experience over time may explain why HTx clinicians assigned comparatively higher values to topics such as “Rejection” and “Transplant CAV”–resulting in no significant difference in educational value compared to HTx recipients/caregivers, and comparatively lower values to topics related to “normal” daily life–resulting in the significant differences in educational values identified. Similarly, studies have indicated for many years that pediatric HTx recipients are at increased risk for obesity and dyslipidemia [19-21], and a recent multi-center study confirmed that obesity at the time of HTx and dyslipidemia 1 year out from HTx are both independent risk factors for CAV and graft loss [22]. These facts taken together may explain why HTx clinicians assigned comparatively higher value to “Physical activity and exercise after HTx.” Interestingly, this comparatively higher value assignment was not seen for “Heart healthy diet and general nutrition after HTx.” Lastly, although not unique to cardiac transplant patients, a notable portion of complications after pediatric HTx continue to be related to medication non-adherence [4-7]. This fact is reflected in the large proportion of educational intervention programs that focus on improving medication compliance [23-27], and is reflected here in the HTx clinicians' assignment of comparatively higher value to topics most directly related to allograft longevity and survival.

Regarding educational values identified among HTx clinicians, the educational values assigned by HTx nurses aligned more closely with those assigned by HTx recipients/caregivers, compared to the educational values assigned by HTx clinicians as a group. In fact, the most significant discrepancies in educational value assigned comparing HTx nurses to APPs and physicians directly matched those comparing HTx recipients/caregivers to HTx clinicians as a group. The differences in values identified comparing individual HTx clinicians are possibly related to the distinct role that each member of the HTx clinical team plays in caring for these patients. In general, HTx nurses may be more intimately involved in the granular aspects of daily care provided to patients in the hospital, as well as the training that enables both patients and caregivers to perform those tasks effectively and independently every day at home. This could be one explanation for why HTx nurses place comparatively greater emphasis on topics related to the details of daily life after transplant.

Turning attention to differences in educational values identified among HTx recipients and caregivers based on the diagnosis of congenital versus acquired heart disease, significant differences were identified in only two topics: “School performance and potential academic considerations after transplant” and “Pregnancy and family planning.” HTx recipients and caregivers in the group with acquired heart disease placed significantly higher value on both of these topics compared to those in the group with CHD, which could reflect more of an investment in future “normal,” or “regular life” activities among these HTx recipients and caregivers. This difference in educational values may be related to the fact that HTx recipients and caregivers in the group with acquired heart disease knew life and could plan for the future before heart disease was even a consideration in their lives. On the other hand, those in the group with CHD likely (if not certainly) never knew life without significant heart disease and had already received anticipatory guidance related to school and family planning for years prior to transplant.

Considering demographic correlates, there were notable differences in educational values assigned to various topics for HTx recipients/caregivers who identified as White compared to those who identified as Black/African-American, Asian, or Multi-Racial. In attempting to understand these value discrepancies, it is critical to recognize that social determinants of health contribute significantly to morbidity and mortality in the pediatric HTx population [28-30]. For example, considering risk factors for medication non-adherence–one of the educational topics that revealed significant value discrepancy comparing these groups–multiple social determinants of health are associated with increased risk of medication non-adherence among pediatric solid organ transplant patients [8]. These risk factors have been shown to include Black race, lower socioeconomic status, poor access to medications, and having public insurance [4, 9]. Focusing on outcome measures, Black race, as an independent variable, has been shown to be associated with greater risk of graft loss across solid organ transplantation groups [31, 32]. Looking specifically at the pediatric HTx population, data from the Pediatric Heart Transplant Society registry revealed that among patients who received ATG (antithymocyte globulin) induction therapy between 2000 and 2020, both Black race and “socioeconomic disadvantage” were associated with late rejection with hemodynamic compromise and graft loss [33]. Given these well-documented associations with poor outcomes, it is possible that our patient/caregiver respondents who identify with those social determinants of health (risk factors) place higher value on educational topics such as those related to medication adherence, be it consciously or subconsciously, to combat the likelihood of those statistics becoming a reality in their lives. As a final example, a topic that revealed one of the greatest differences in educational values assigned in this study was “COVID-19-related topics.” The COVID-19 epidemic is a prime example of how social determinants of health continue to disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States [34]. Given the inherent risks that certain social determinants of health incur on some groups over others, it is understandable that the groups negatively impacted by these risk factors would place higher value on educational topics that could help reduce related modifiable risk factors and help keep their loved ones safe.

Disparities in HTx outcomes have been thoroughly investigated and described in the literature, and one persistent conclusion is that health education and literacy is one of the strongest social determinants of health for these and other patients [4, 31, 33, 35, 36]. The discrepancies in educational values between race groups revealed in this study may be a signal that HTx transplant education, in general, does not support the priorities of some patients who identify with a racial minority group. It is possible that these patients are affected by both implicit and explicit biases in their experience with the multidisciplinary HTx team, as well as the education they receive after HTx [28, 37, 38].

Regular, open conversation between these two central stakeholders regarding the evolution of educational priorities after HTx will afford HTx providers the opportunity to reinforce standardized topics of education that become more important to specific HTx recipients and caregivers at any given time. Additionally, ongoing assessments of educational priorities will enable providers to identify potential gaps in HTx recipient and caregiver understanding of important aspects of post-HTx self-care, and then provide individualized education to bridge those gaps. The goal of a standardized approach to post-HTx education is not to create a one-size-fits-all program that can be set to autopilot. The goal of a standardized approach to post-HTx education is to create a set of educational topics and content that have been proven to be meaningful for HTx recipients and caregivers, stimulate interest and active engagement in self-care after HTx, and, as a result, better enable HTx clinicians to individualize continued education and shared understanding of optimal self-care after HTx.

This study has limitations that are important to acknowledge. First, given the nature of recruitment methods, both selection and response biases are present, and results are unlikely to be generalizable to all pediatric HTx recipients, caregivers, and clinicians. Another limitation is that only a small number of the respondents were HTx recipients (3%). It is possible that their lack of response as a group (even through social media) is a reflection of how they view their own role in driving communication, education, and self-care after HTx. Alternatively, perhaps studying HTx recipients > 18 years old in a future study would gain better insight into the HTx recipient perspective, as adolescents may not be active on the forums from which our study recruited. Considering the responses that we did receive from HTx recipients in this study, we acknowledge that the small number of responses is not a meaningful representation of the entire pediatric HTx patient population. However, authors chose to include those responses in the data analysis because this was a HTx recipient/caregiver stakeholder-partnered research study, and as such, they believe it is important that all HTx recipient voices be expressed in the results despite the low response rate. Further, a post hoc sensitivity analysis supported continued inclusion of these patient voices in the overall dataset, as detailed in Table 2. Another limitation was the lack of diversity within HTx recipient/caregiver respondents, with 90% identifying as White. Further, the majority of HTx recipients/caregivers were college graduates whose annual household income was reported as > $100 000. The lack of diversity in racial and socioeconomic representation among our respondents is a notable limiting factor to the generalizability of our results. While this is a common limitation of social media-based recruitment, it is important that we continue to utilize multi-method recruitment approaches (i.e., clinic-based recruitment) to diversify research representation. Lastly, while the educational topics included on the survey were taken from local and national well-respected resources, the survey was investigator-designed, and has not been previously validated.

| Questionnaires | Original | Excluding 4 HTx recipient | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTx recipient/Caregiver of HTx recipient (N = 77) | Provider (N = 43) | Mean difference ± SD | p § | Caregiver of HTx recipient (N = 73) | Provider (N = 43) | Mean difference ± SD | p § | |

| Routine medical care after heart transplant | ||||||||

| Frequency of follow-up clinic visits and common topics discussed at these visits | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 0.88 ± 1.5 | 0.003 | 9.2 ± 1.4 | 8.3 ± 1.7 | 0.90 ± 1.5 | 0.003 |

| Frequency of testing: Labs, electrocardiograms, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterizations, stress testing, etc. | 9.1 ± 1.3 | 8.4 ± 1.7 | 0.75 ± 1.5 | 0.01 | 9.1 ± 1.3 | 8.4 ± 1.7 | 0.75 ± 1.5 | 0.01 |

| Purpose of previously mentioned testing, and significance of results | 8.9 ± 1.7 | 8.8 ± 1.4 | 0.11 ± 1.6 | 0.71 | 8.9 ± 1.8 | 8.8 ± 1.4 | 0.09 ± 1.6 | 0.77 |

| Immunizations or vaccines after heart transplant | 7.7 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 1.4 | −0.04 ± 2.3 | 0.92 | 7.7 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 1.4 | 0.04 ± 2.3 | 0.92 |

| Medications: familiarity and understanding | ||||||||

| Frequency and dosing of medications | 9.6 ± 0.95 | 9.6 ± 1.4 | −0.04 ± 1.2 | 0.88 | 9.5 ± 0.97 | 9.6 ± 1.4 | −0.05 ± 1.2 | 0.85 |

| Function or purpose of medications | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 0.37 ± 1.2 | 0.11 | 9.2 ± 1.2 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 0.35 ± 1.2 | 0.13 |

| How foods and other medications can affect transplant-specific medications | 9.1 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.002 | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 1.2 ± 1.7 | 0.002 |

| Side-effects associated with different transplant medications | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 0.45 ± 1.6 | 0.16 | 9.0 ± 1.7 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 0.52 ± 1.6 | 0.10 |

| Complications after heart transplant | ||||||||

| Rejection: prevalence, symptoms, subtypes, expected graft-survival (how long newly transplanted hearts commonly last) | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 9.5 ± 0.81 | 0.01 ± 0.96 | 0.96 | 9.6 ± 0.85 | 9.5 ± 0.81 | 0.10 ± 0.83 | 0.55 |

| Transplant cardiac allograft vasculopathy (problems with the transplanted coronary arteries) | 8.9 ± 1.8 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 0.21 ± 1.6 | 0.46 | 8.9 ± 1.8 | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 0.25 ± 1.6 | 0.39 |

| Hypertension (high blood pressure) | 8.1 ± 1.9 | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 0.27 ± 1.8 | 0.43 | 8.1 ± 1.9 | 7.9 ± 1.5 | 0.25 ± 1.8 | 0.47 |

| Infections, common viruses, and bacteria that affect transplant patients | 9.2 ± 1.1 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 1.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.0001 | 9.3 ± 1.0 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | < 0.0001 |

| Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (cancer associated with transplant) | 8.9 ± 1.5 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.89 ± 1.4 | 0.002 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.93 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| Physical and psychosocial topics | ||||||||

| Physical activity and exercise after transplant | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.47 ± 1.6 | 0.13 | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 0.44 ± 1.6 | 0.16 |

| Importance and meaning of a “heart healthy diet” and general nutrition after transplant | 8.3 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 0.78 ± 1.8 | 0.03 | 8.2 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | 0.73 ± 1.8 | 0.04 |

| Mental health after transplant | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.81 ± 1.4 | 0.002 | 9.2 ± 1.5 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | 0.83 ± 1.4 | 0.002 |

| School performance and potential academic considerations after transplant (making up for missed time in school, achieving individual goals, etc.) | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 0.61 ± 1.9 | 0.054 | 8.1 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 0.70 ± 1.8 | 0.02 |

| COVID-19 concerns and considerations for transplant patients | 6.7 ± 2.7 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 0.75 ± 2.6 | 0.13 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 0.68 ± 2.5 | 0.17 |

| Pregnancy and family planning | 5.9 ± 3.3 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | −0.73 ± 2.9 | 0.16 | 5.8 ± 3.3 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | −0.79 ± 2.9 | 0.13 |

| Restrictions including sports, pets, activities, and careers | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 1.7 ± 2.2 | 0.0002 | 7.9 ± 2.1 | 6.3 ± 2.4 | 1.6 ± 2.2 | 0.0003 |

- Note: Data are presented as Mean ± SD. Highlighted bold values are statistically significant.

- § p-value from two-sample t-test.

In sum, this is the first national study to characterize and compare adolescent HTx recipient, caregivers of pediatric HTx recipients, and pediatric HTx clinician values regarding post-HTx educational topics. The differences in educational values identified in this study will be a valuable first step in creating a meaningful, comprehensive, and effective approach to patient/caregiver-driven post-HTx education. More critically, however, the difference in overall perspective on life after pediatric HTx revealed by these results should influence clinicians' current approach to every patient/caregiver encounter after HTx. A standardized approach to providing optimal post-HTx education must be dynamic in nature and must maintain the central goal of prioritizing HTx recipient and caregiver values throughout each stage of post-HTx care. Future studies will aim to determine the effects of incorporating identified HTx recipient/caregiver educational priorities into educational programs on objective outcomes measures, with graft survival as the primary outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Michigan Congenital Heart Outcomes Research and Discovery (M-CHORD) Program. The participating transplant center was C.S. Mott Children's Hospital/University of Michigan. Participating national organizations included the Pediatric Heart Transplant Society, Transplant Families, and Enduring Hearts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.