Retrospective Cohort Study of Associated Factors for Intestinal Complications in Pediatric Liver Transplantation

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

Intestinal complications (IC) represent serious adverse events after liver transplantation (LT), however limited research has been conducted in pediatric cohorts. This study aims to describe IC after pediatric LT and to identify associated factors.

Methods

Retrospective review of 153 patients having undergone LT, aged 0–18 years, treated in the Swiss Pediatric Liver Center in Geneva. Pre-, per- and postoperative data were analyzed. IC were defined as pathologies or lesions directly associated with LT and attributable to the surgical procedure.

Results

16/153 (11%) patients developed IC: 10/16 mechanical obstructions, 4/16 intestinal perforations and 2/16 sub-mesocolic abscesses. IC patients had a significantly lower Body Mass Index (BMI) (15.5 vs. 16.4, p = 0.019). Children with IC had significantly higher incidence of previous Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy associated with Ladd procedure (13% vs. 2%, p = 0.055), a history of intraoperative iatrogenic intestinal perforation(s) (31% vs. 5%, p = 0.003) and prolonged LT surgery duration (536 vs. 415 min, p = 0.007). Significantly more children with IC had received basiliximab (69% vs. 40%, p = 0.048). Patients with IC exhibited a higher incidence of post-LT sub-occlusions (p < 0.001) and an increased requirement for post-LT parenteral nutrition (p = 0.027). Additionally, IC patients underwent significantly more reoperations (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

One in 10 children post-LT experiences IC, which are associated with significant morbidity. Pre-LT nutritional status appears as an associated factor with IC, along with the necessity for adhesiolysis during LT, often leading to prolonged operative time. These associated factors should alert medical teams to promote early IC diagnosis in patients after LT.

Abbreviations

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CMV

-

- cytomegalovirus

-

- EBV

-

- Epstein–Barr virus

-

- GRWR

-

- graft-to-recipient-weight-ratio

-

- IC

-

- intestinal complication

-

- ICU

-

- Intensive care unit

-

- IQR

-

- Interquartile range

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- MELD

-

- model for end-stage liver disease

-

- PELD

-

- pediatric end-stage liver disease

1 Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) is the main therapeutic approach for end-stage liver diseases in pediatric patients [1, 2]. The occurrence of surgical complications following LT remains a significant challenge, with intestinal complications (IC) being among the concerning [3-11]. The incidence of IC following LT in the pediatric population has been reported to range from 2.75% to 20% [3-11]. The post-IC mortality rate has been reported to be as high as 25%–50% [3-7]. These values highlight the severe impact of IC on pediatric LT recipients. Yet, research has predominantly focused only on incidence and morbidity rates, very few reports aimed at identifying potential factors associated with IC. Thus, this study aimed to analyze the incidence of the different IC post-LT and identify factors associated with their occurrence in the pediatric population. By identifying these associated factors, we aim to anticipate the onset of these complications and, in the future, intervene on modifiable parameters to improve patient outcome.

2 Patients and Methods

This single-center retrospective descriptive study included children aged 0–18 years at LT between 2002 and 2021. Patients who received multi-organ transplants were excluded from the study. Patients were categorized into two groups: those who experienced IC following LT and those who did not. The incidence of IC was evaluated throughout the entire follow-up period, which ended on November 30, 2022 for ongoing follow-up cases, or until the death of the patient. Of note, the Swiss Pediatric Liver Center is the sole national center in Switzerland performing pediatric LT. All patients transplanted in our center have a centralized follow-up, i.e. are seen at least once a year in Geneva, with external medical reports from referring hospitals transferred, ensuring complete medical charts. A prospective centralized database is maintained for all patients, including relevant data and information from external institutions.

Intestinal complications were defined as pathologies or lesions directly resulting from the LT procedure and attributable to the surgical procedure. These included intestinal perforations, mechanical obstructions (e.g., intestinal hernias, intestinal plicature) defined as a complete intestinal obstruction needing a surgical investigation or treatment and complications of infectious origin (e.g., deep sub-mesocolic abscess).

Nutritional support was given both during the pre- and post-LT period as needed, either as partial or total administration of caloric needs by feeding tubes or intravenously. Before LT, due to the increased energy requirements in patients with chronic liver disease, caloric intake was generally targeted at a minimum of 120% of the recommended dietary allowance to prevent malnutrition or muscle wasting. Following LT, enteral nutrition was reintroduced as soon as it was considered clinically feasible, typically by day three. If there were relative or absolute contraindications to enteral feeding, parenteral nutrition was initiated also starting from day three and gradually reduced and replaced by enteral feeding based on the patient's clinical status.

The majority of patients received immunosuppression as follows: (i) tacrolimus with a target level of 10–12 μg/L during the first month post-LT; (ii) basiliximab administered on day 0 and day 4 post-LT per manufacturer recommendations; (iii) corticosteroids administered at 1 mg/kg/d from day 0 to day 30, 0.5 mg/kg/d during the second month after LT and 0.25 mg/kg for the third month post LT. Patients undergoing LT for hepatoblastoma did not receive basiliximab and received a combination of low dose tacrolimus and an mTOR inhibitor from post-op day 90.

Patient data were collected from electronic medical records and organized into several categories, including pre-, peri- and post-LT variables. These categories included patient demographics, pre-LT diagnoses and comorbidities, surgical history pre-LT, laboratory values, donor and graft details, peri- and post-LT data and type and time of onset of post-LT IC.

2.1 Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), represented by the first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3). The Mann–Whitney test was employed to compare continuous variables. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and analyzed using the chi-square test and Cramer's V test for comparison between the IC and non-IC groups. The survival rate of patients was computed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using the “R project for statistical Computing” software. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. Kaplan–Meier curves and graphical representations were generated using Graphpad's Prism software and Excel.

This study was approved by the ethics committee (CER11-010-r/MATPED 11-004R).

3 Results

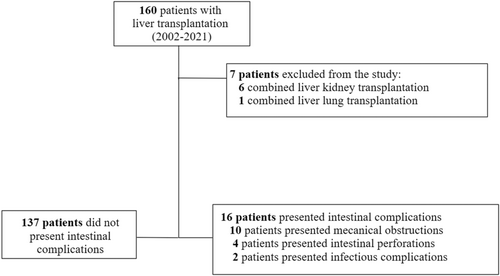

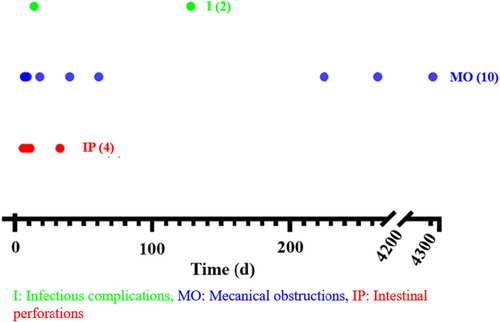

A total of 160 pediatric LT were performed during the study period and 153 patients met the inclusion criteria. Among these patients, 16 (11%) experienced IC. They were classified into three types: 10 mechanical obstructions (7% of the entire cohort), four intestinal perforations (3%) and two infectious complications (1%, sub-mesocolic abscesses) (Figure 1; Table 1).

| Number of intestinal complication | Type of intestinal complication | Time (days)a | Treatment type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Internal hernia | 4381 | Surgical |

| 2 | Mechanical obstruction | 264 | Surgical |

| 3 | Mechanical obstruction | 225 | Surgical |

| 4 | Sub-mesocolic abscess | 128 | Surgical |

| 5 | Mechanical obstruction | 61 | Surgical |

| 6 | Mechanical obstruction | 40 | Conservative |

| 7 | Colon perforation | 33 | Surgical |

| 8 | Mechanical obstruction | 18 | Surgical |

| 9 | Sub-mesocolic abscess | 14 | Surgical |

| 10 | Ileal perforation | 11 | Surgical |

| 11 | Mechanical obstruction | 9 | Surgical |

| 12 | Ileal perforation | 9 | Surgical |

| 13 | Mechanical obstruction | 8 | Surgical |

| 14 | Mechanical obstruction | 7 | Surgical |

| 15 | Mechanical obstruction | 7 | Conservative |

| 16 | Ileal perforation | 6 | Surgical |

- a Time interval between liver transplantation and diagnosis of intestinal complication.

The median age of patients developing IC was 2.1 years (IQR: 1.1–4.9). Mechanical obstruction occurred between day 7 and day 4382 (12 years) post-LT. Intestinal perforations were observed between day 6 and day 33 post-LT, while the two infectious complications occurred on day 14 and day 128 post-LT (Figure 2).

Of the 16 patients with IC, 14 required re-operation for treatment, while two were managed conservatively. Of note, all patients with intestinal perforations or infectious complications had biliary atresia as their primary diagnosis (Table 1).

3.1 Recipient Characteristics

Recipient characteristics are detailed in Table 2. Most variables did not significantly differ between the two groups with and without IC, except two. First, patients with IC had a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) compared to patients without IC (15.5 vs. 16.4, p = 0.019). Second, patients with IC had a higher incidence of previous Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy combined with the Ladd procedure (13% vs. 2%, p = 0.055).

| Total | Patients without IC | Patients with IC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 153 | 137 (89%) | 16 (11%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| W | 67 (44%) | 63 (46%) | 4 (25%) | 0.182 |

| Age at LT (months) | 22 (11–109) | 25 (11–110) | 17 (10–45) | 0.340 |

| Weight at LT (kg) | 11.4 (7.8–29) | 12.2 (7.7–31) | 9.6 (8.8–12.2) | 0.389 |

| z-score weight | −0.51 (−0.7–0.5) | −0.46 (−0.7–0.6) | −0.61 (−0.7–0.5) | 0.389 |

| Height (cm) | 84 (70–130) | 84 (70–131) | 81 (72–91) | 0.657 |

| z-score height | −0.43 (−0.8–0.8) | −0.43 (−0.8–0.9) | −0.53 (−0.8–0.2) | 0.657 |

| BMI | 16.27 (15.2–18.1) | 16.35 (15.2–18.4) | 15.5 (14.5–16.7) | 0.019 |

| z-score BMI | −0.28 (−0.6–0.3) | −0.25 (−0.6–0.4) | −0.53 (−0.9–0.1) | 0.019 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Cholestatic disease | 105 (69%) | 91 (66%) | 14 (88%) | 0.532 |

| Metabolic disease | 28 (18%) | 27 (20%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Oncological disease | 7 (5%) | 7 (5%) | 0 | |

| Other | 13 (9%) | 12 (9%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 98 (64%) | 87 (64%) | 11 (69%) | 0.890 |

| PELD score | 12.26 (0–21) | 11.09 (0–21) | 12.66 (3.6–20.5) | 0.630 |

| MELD score | 16 (9–21.2) | 16.93 (9–22.5) | 11.19 (11–16) | 0.328 |

| Surgery history pre-LT | 59 (39%) | 54 (39%) | 5 (31%) | 0.716 |

| Kasai | 62 (41%) | 54 (39%) | 8 (53%) | 0.445 |

| Kasai + Ladd | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (13%) | 0.055 |

| Time between Kasai and LT(d) | 339 (225–1835) | 340 (237–1505) | 270 (196–1835) | 0.750 |

| Other abdominal surgeries pre-LT | 55 (36%) | 52 (38%) | 3 (19%) | 0.215 |

| Time between surgery and LT(d) | 281 (128–632) | 272 (132–623) | 383 (75–1340) | 0.727 |

| Corticosteroid treatment pre-LTa | 14 (9%) | 13 (10%) | 1 (6%) | 0.999 |

| NSAID treatment pre-LTb | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Antibiotics pre-LTb | 56 (37%) | 51 (37%) | 5 (31%) | 0.845 |

| Polysplenia | 12 (8%) | 10 (7%) | 2 (13%) | 0.364 |

| Digestive hemorrhage pre-LT | 30 (20%) | 27 (20%) | 3 (19%) | 0.999 |

| Chemotherapy pre-LT | 9 (6%) | 8 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 0.999 |

- Note: Results are either expressed as number (%), or median (IQ1–IQ3).

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; d, days; MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; PELD, pediatric end-stage liver disease.

- a One year pre-LT.

- b One week pre-LT.

Recipient variables immediately before LT are summarized in Table 3. There were no significant differences between the two groups of patients, except serum creatinine levels, which showed a trend to be lower in children with IC than in those without IC (2.3 mg/L vs. 3.3 mg/L, p = 0.059).

| All patients | Patients without intestinal complication | Patients with intestinal complication | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 153 | 137 (89.5%) | 16 (10.5%) | |

| CRP increased | 25 (16.3%) | 22 (16.1%) | 3 (18.8%) | 0.727 |

| ASAT (IU/L) | 132 (76–225) | 129 (72–211) | 155 (90–235) | 0.438 |

| ALAT (IU/L) | 76.5 (44163) | 76.5 (44–163) | 75.5 (39.8–174) | 0.855 |

| Gamma-GT (U/L) | 90 (40–215) | 90 (39–215) | 91 (48–184) | 0.554 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 130 (27–360) | 171 (27–363) | 76 (31–222) | 0.200 |

| Factor V (%) | 57 (38–93) | 57 (37–94) | 58 (50–81) | 0.911 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 98 (83–115) | 99 (83–115) | 96 (82–111) | 0.644 |

| Leucocytes (g/L) | 7.8 (4.2–11.6) | 7.7 (4.2–11.5) | 8.8 (5.4–12.1) | 0.723 |

| Neutrophiles (g/L) | 3.7 (2.2–6.1) | 3.6 (2.2–5.7) | 4.9 (2.2–8.1) | 0.325 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 3 (2.6–3.6) | 3.1 (2.7–3.6) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 0.157 |

| Phosphate (g/L) | 1.6 (1.3–1.8) | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) | 1.6 (1.3–1.7) | 0.972 |

| Ca (g/L) | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) | 2.3 (2.2–2.4) | 2.2 (2.1–2.4) | 0.248 |

| Urea (g/L) | 3.6 (2.4–5.2) | 3.6 (2.5–5.2) | 3.35 (2.3–5.4) | 0.754 |

| Creatinine (mg/L) | 3.1 (2.0–4.0) | 3.3 (2.0–4.0) | 2.3 (1.0–3.0) | 0.059 |

| Thrombocytes (g/L) | 108 (62–82) | 107 (61–180) | 159 (93–203) | 0.207 |

| INR | 1.19 (1–1.5) | 1.2 (1–1.5) | 1.15 (1–1.4) | 0.688 |

| CMV positive | 83 (54%) | 77 (56%) | 6 (38%) | 0.248 |

| EBV positive | 52 (34%) | 46 (34%) | 6 (38%) | 0.972 |

| Location pre-LT | ||||

| Home | 84 (55%) | 74 (54%) | 10 (63%) | 0.763 |

| Hospital | 26 (17%) | 23 (17%) | 3 (19%) | |

| ICU | 43 (28%) | 40 (29%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Parenteral nutrition pre-LT | ||||

| Total | 13 (9%) | 11 (8%) | 2 (12%) | 0.628 |

| Partial | 4 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 0.360 |

- Note: Variables are based on a maximum lead time of 24 h before LT. Results are either expressed as number (%) or median (IQ1–IQ3).

3.2 Donor and Graft Characteristics

Donor and graft characteristics are represented in Table 4. No significant differences were observed between the two groups of patients.

| All patients | Patients without intestinal complication | Patients with intestinal complication | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 153 | 137 (89%) | 16 (11%) | |

| Donor type | ||||

| Deceased | 140 (92%) | 126 (92%) | 14 (88%) | 0.628 |

| Living | 13 (9%) | 11 (8%) | 2 (13%) | |

| CMV donor | 63 (41%) | 58 (42%) | 5 (31%) | 0.559 |

| EBV donor | 97 (63%) | 83 (61%) | 14 (88%) | 0.066 |

| Graft | ||||

| Right liver | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 0.066 |

| Whole liver | 55 (36%) | 53 (39%) | 2 (12%) | |

| Left liver | 4 (2.6%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Reduced liver | 2 (1.3%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Right lobe | 4 (2.6%) | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Left lobe | 81 (53%) | 69 (51%) | 12 (75%) | |

| Monosegment | 3 (2%) | 3 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| GRWR (%) | 2.8 (1.9–3.8) | 2.8 (1.9–3.8) | 2.6 (1.8–3.2) | 0.373 |

| Cold ischemia time (min) | 318 (268–386) | 328 (271–387) | 296 (227–363) | 0.364 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) | 55 (46–65) | 55 (46–65) | 58 (49–69) | 0.356 |

| Total time of ischemia (min) | 372 (321–445) | 379 (323–447) | 353.5 (278–418) | 0.341 |

- Note: Results are either expressed as number (%) or median (IQ1–IQ3).

- Abbreviations: CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein–Barr virus; GRWR, graft-to-recipient-weight-ratio.

3.3 Peri-Transplant and Post-Transplant Variables Until the End of Follow-Up

Table 5 summarizes the peri-LT and immediate post-LT variables. Operating time was significantly different between the two groups, patients who experienced IC had longer operative time (536 min vs. 415 min, p = 0.007). Furthermore, patients with IC presented with more peri-operative iatrogenic intestinal perforations (31.2% vs. 5.1%, p = 0.003).

| All patients | Patients without intestinal complication | Patients with intestinal complication | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 153 | 137 (89%) | 16 (11%) | |

| Operation duration (min) | 423 (72–542) | 415 (69–534) | 536 (458–594) | 0.007 |

| Ascites | ||||

| None | 52 (34%) | 47 (35%) | 5 (31%) | 0.645 |

| Little | 48 (32%) | 44 (32%) | 4 (25%) | |

| Moderated | 33 (22%) | 30 (22%) | 3 (19%) | |

| Severe | 19 (12%) | 15 (11%) | 4 (25%) | |

| Perioperative intestinal perforation | 12 (8%) | 7 (5%) | 5 (31%) | 0.003 |

| Ia | 1 (7%) | |||

| MOb | 2 (12%) | |||

| IPc | 2 (12%) | |||

| Blood transfusion (mL) | 33 (0–80) | 34 (0–80) | 32 (13–65) | 0.966 |

| Biliary anastomosis | ||||

| Bilio-enteric anastomosis | 139 (91%) | 123 (90%) | 16 (100%) | 0.908 |

| Duct-to-duct anastomosis | 14 (9%) | 14 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Roux-en-Y | ||||

| De novo during LT | 93 (67%) | 83 (68%) | 10 (63%) | 0.908 |

| From Kasai | 46 (33%) | 40 (33%) | 6 (38%) | |

| Associated surgical procedures during LT | 48 (31%) | 43 (31%) | 5 (31%) | 0.999 |

| Intubation duration post-LT (days) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–6) | 4 (1–8) | 0.900 |

| Use of norepinephrine post-LT | 21 (14%) | 18 (13%) | 3 (19%) | 0.463 |

| Duration of ICU stay (days) | 7 (5–11) | 7 (5–11) | 10.5 (6–17) | 0.181 |

- Note: Results are either expressed as number (%), or median (IQ1–IQ3).

- a Part of the patients with perioperative perforations who presented infectious complications.

- b Part of the patients with perioperative perforations who presented mechanical obstructions.

- c Part of the patients with perioperative perforations who presented intestinal perforations.

Post-LT variables are detailed in Table 6. Patients with IC had more frequently received Basiliximab post-LT compared to the non-IC group (69% vs. 40%, p = 0.048). Additionally, patients with IC experienced a significantly higher rate of occlusive syndromes post-LT (p < 0.001) and required more post-operative parenteral nutrition (p = 0.027). Patients with IC required more abdominal re-operations post-LT compared to those without IC (88% vs. 26%, p < 0.001).

| All patients | Patients without intestinal complication | Patients with intestinal complication | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 153 | 137 (89%) | 16 (11%) | |

| Abdominal drain colonization | 7 (5%) | 5 (4%) | 2 (123%) | 0.158 |

| Positive bacteriemiaa | 40 (26%) | 36 (26%) | 4 (25%) | 0.999 |

| Post-LT hemorrhageb | 11 (7%) | 11 (8%) | 0 | 0.607 |

| Nutrition | ||||

| Total parenteral nutrition | 25 (16%) | 19 (14%) | 6 (38%) | 0.027 |

| Partial parenteral nutrition | 10 (7%) | 10 (7%) | 0 | 0.600 |

| Continuous, nasogastric tube | 22 (14%) | 17 (12%) | 5 (31%) | 0.057 |

| Fractionated, nasogastric tube | 35 (23%) | 31 (23%) | 4 (25%) | 0.762 |

| Immunosuppression | ||||

| Corticosteroids |

111 (73%) |

102 (75%) |

9 (56%) |

0.143 |

| Tacrolimus | 144 (94%) | 129 (94%) | 15 (94%) | 0.999 |

| Sirolimus | 3 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Basiliximab | 65 (43%) | 54 (39%) | 11 (69%) | 0.048 |

| Hospitalization duration (days) | 25 (19–35) | 25 (19–33) | 29 (23–46) | 0.135 |

| Complications post-LT | ||||

| Occlusive syndrome | 13 (9%) | 3 (2%) | 10 (63%) | 0.001 |

| Incisional hernia | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 |

| Rejectionc | 44 (29%) | 38 (28%) | 6 (38%) | 0.398 |

| Re-operation | 50 (33%) | 36 (26%) | 14 (88%) | 0.001 |

| Vascular | 16 (45%) | 0 | ||

| Biliary | 9 (25%) | 0 | ||

| Others | 8 (22%) | 0 | ||

| Abdominal wall | 3 (8%) | 0 | ||

| Intestinal | 0 (0%) | 14 (100%) | ||

| Re-transplantation | 9 (6%) | 9 (6%) | 0 | 0.599 |

| Chemotherapies post-LT | 5 (3%) | 5 (3%) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Follow up duration (years) | 7 (3.5–12) | 7 (3.2–12) | 8 (4.9–13) | 0.460 |

| Patient status | ||||

| Alive | 140 (92%) | 124 (91%) | 16 (100%) | 0.363 |

- Note: Results are either expressed as number (%) or median (IQ1–IQ3).

- a Values considered until the end of LT hospitalization.

- b Hemorrhage needing a blood transfusion.

- c Rejection during the first 3 months post-LT.

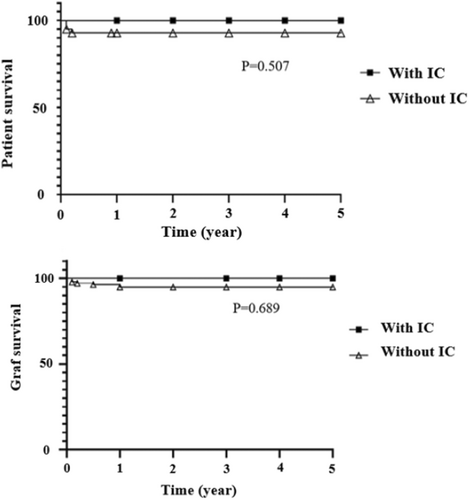

Mortality after IC was zero and the occurrence of IC post-LT did not have a statistically significant impact on patient or graft survival (Figure 3).

4 Discussion

The present study reveals that more than one in 10 pediatric LT patients may experience a post-LT IC, with the most frequent being mechanical obstruction, followed by intestinal perforations. The incidence of IC has been reported to range from 2.75% to 20% [3-11], with only a few studies performing a stratification according to the type of IC. Similar to our findings (7% mechanical obstruction), Sun et al. [11] reported a 5.9% incidence of mechanical obstructions. In their report, this IC was also the most frequent, with intestinal perforation being the second most common [11]. Post-LT intestinal perforation occurrence was described in literature within a range of 2.5%–19% [3-6]. This complication was rare in our cohort, with only 4 of 153 patients (2.6%) presenting this severe complication. Of note, for adhesiolysis we exclusively use the bipolar technique and nearly never the monopolar, which may contribute to fewer heat-related lesions and consequently fewer secondary intestinal perforations due to wall weakening [12]. As for the incidence of infectious IC, we were unable to find comparable data in the literature.

The occurrence of IC did not significantly affect patient or graft survival in our study. We had no IC-related mortality. These results contrast with post-IC mortality rates of 25%–50% reported in the literature [3-10]. It is difficult to reveal the reasons for our low mortality. It may be attributed to the fact that all patients were operated on and meticulously followed by a highly specialized, small and thus rarely changing team, being extremely attentive, and despite the small size of our center, having a high-performance environment and long-standing experience.

Dehghani et al. [7] observed an average of 7 days between LT and the onset of IC, while Sun et al. [11] reported an average of 34 days. In this later study, several patients presented with mechanical obstructions many years after LT. These results must be interpreted with caution as the probability of obstructive IC, primarily mechanical ileus, increases over time due to post-surgical adhesions [11]. More specifically, Barila et al. showed that intestinal perforations typically occurred around 10 days post-LT [6]. Of note, in our study, intestinal perforations were diagnosed up to 33 days after LT. It is important to note that most of our patients were on corticosteroid treatment post-LT, which is known to mask the symptoms of this type of IC.

4.1 Associated Factors for Intestinal Complications

The literature reports that low-weight or younger age are AF for IC following pediatric LT [5, 6]. Indeed, our study also found that patients with IC had a lower BMI and a tendency toward lower creatinine serum levels, possibly reflecting a sarcopenic condition. In our study, patient weight did not appear to be significantly different between the two groups. These findings reinforce the importance of monitoring nutritional status prior to LT particularly focusing on the patient's muscle mass. The current literature suggests sarcopenia as a potential AF for post-LT complications [13, 14].

According to Sun et al. [11], a high graft-to-recipient weight ratio (GRWR), is a risk factor for IC. However, in our study, no data directly related to the graft emerged as significant: neither the type of donor, the type of graft or the GRWR.

In our study, patients with a diagnosis of biliary atresia (BA) were more likely to develop IC, in particular intestinal perforations and obstructions. Indeed, the BA-associated surgical history increases the risk for peri-LT intestinal perforations during hepatectomy due to bowel adhesions in a terrain of portal hypertension and later for mechanical obstructions due to the same reasons. Even if intraoperative iatrogenic intestinal perforations are treated with direct suturing, they present a risk of reperforation post-LT and increase the likelihood of developing intestinal adhesions. Our findings indicate that a history of surgery, specifically a Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy associated with a Ladd's procedure, increased the risk of IC. Interestingly, in our cohort, the Kasai operation alone was not identified as a significant AF. The association of a Kasai operation associated with a Ladd's procedure is a longer and more extensive operation, increasing the risk of developing more extensive adhesions and therefore increasing the risk of IC. In this study, total operating time emerged as a significant AF for IC, consistent with the literature [3, 7]. This variable might serve as a surrogate marker related to the necessity of sometimes time-consuming adhesiolysis yet may also be seen as an absolute risk factor. The longer the abdomen is open and the intestines are exposed to the environment, the more intense the local and systemic inflammatory response, thereby increasing the risk of complications [15, 16]. Do these observations provide sufficient reason to suggest that the Kasai operation ultimately jeopardizes BA patients who require LT? After carefully weighing the pros and cons, as also thoroughly analyzed in a recent paper by Davenport and Superina [17], we maintain that, in experienced hands, the risk of IC from prior surgeries, such as the Kasai (and Ladd procedure), does not outweigh the Kasai's benefits. Therefore, hepatoportoenterostomy should still be performed for BA patients, employing no-touch techniques and minimizing handling of the intestines and liver whenever possible.

According to Aslan et al. [5], high intra-operative blood loss is a risk factor for IC, mainly for intestinal perforation. This hypothesis is also supported by the team of Sun et al. [11] who found that patients with mechanical obstructions received more intra-operative blood plasma transfusions, explained by the precarious state of the patients prior to LT. Yet, in our analysis, the amount of blood transfusions was not found to be significantly different between the two groups. This said, we did not investigate plasma transfusions.

Interestingly, in our study, patients who received Basiliximab post-LT were significantly more likely to develop IC. Indeed, Lin et al. identified that all patients who experienced intestinal perforations had received Basiliximab; however, the sample size of the study was insufficient to establish a statistically significant association between the two variables [18]. Since the drug effect of Basiliximab persists for approximately 4–6 weeks following administration [18], which coincides with the typical timeframe for the development of IC, there is a question of potential causality. The adverse effects of Basiliximab are rarely discussed in the literature and no studies have documented post-LT IC in pediatric patients who have been administered Basiliximab. It would be relevant to investigate this correlation in a larger prospective study, to determine the potential impact of Basiliximab on the occurrence of IC, in particular intestinal perforations and infectious IC.

Literature also highlights post-LT factors that may represent AF for IC. Indeed, recipient CMV infection has been considered an IC-AF, mainly for intestinal perforations [4, 5]. Furthermore, the administration of corticosteroids may increase the risk of IC, especially intestinal perforations, particularly in the presence of a CMV infection [4, 5]. In our study, CMV status and corticosteroid administration did not differ significantly between the two groups.

4.2 Morbidity of Intestinal Complications

Patients with IC globally had a higher incidence of post-LT reoperations compared to those without IC. In our study, 88% of patients with IC required reoperation, the treatment of IC being mostly surgical. It is however, important to consider that any reoperation may also increase the risk for IC as it increases the abdominal inflammatory state of the patient.

In patients with IC, increased post-LT (sub)occlusive syndromes and a higher need for parenteral nutrition before IC diagnosis were observed. The presence of these indicators may be considered a possible IC precursor which should increase the vigilance of the treating physicians.

5 Conclusion

One in 10 children post-LT experiences IC. Although IC are associated with significant morbidity and often require re-operations for treatment, our study did not reveal any impact on patient or graft survival. Pre-LT nutritional status, as reflected by BMI, was identified as modifiable AF for IC. Patients with a history of substantial abdominal operations prior to LT and increased LT operating time appeared to have an elevated risk for IC. Administration of Basiliximab appeared to negatively impact the occurrence of IC. (Sub)occlusive syndromes and the necessity of post-LT parenteral nutrition may serve as indicators of potential IC occurrence. The presence of these associated factors should increase the suspicion for IC and alert medical teams to allow for early IC diagnosis in children after LT.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dieter Hahnloser for his constructive input.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.