Does symbolic representation matter? A meta-analysis of the passive-symbolic representation link

Abstract

The theory of symbolic representation expects that passive representativeness of bureaucrats can heighten agencies' perceived legitimacy and enhance citizen outcomes. Empirical evidence on the consequences of symbolic representation, however, is mixed. By performing a meta-analysis of 286 effect sizes, this study finds a significantly positive, though weak, association between passive representation and its anticipated symbolic outcomes. A meta-regression analysis further examined how the salience of symbolic representation is moderated by multiple aspects of passive representativeness, symbolic outcomes, policy and geographical contexts, and research design. Results suggest that the symbolic benefits of passive representation are more observed at the frontline than in managerial settings, and the effects are stronger in experimental research designs than observational ones. This research echoes the increasing attention dedicated to the importance of context to representative bureaucracy research and contributes to a more refined theoretical exploration of symbolic representation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Representation bureaucracy has been shown to benefit public organizational performance and citizens in multiple ways (Cepiku & Mastrodascio, 2021; Ding et al., 2021; Riccucci & Van Ryzin, 2017). In these discussions, two primary mechanisms have been conceptualized: active and symbolic representation (Meier, 1975; Theobald & Haider-Markel, 2009). Active representation occurs when bureaucrats share the values of their clients, which affects their decisions and encourages them to act in the interests of those they represent (Andersen, 2017). Meanwhile, a representative bureaucracy that demographically reflects society (known as passive representation) itself carries symbolic value (Mosher, 1968). Even without the active efforts of bureaucrats, their representativeness can independently promote citizens' attitudes toward the agencies they represent. It may also encourage cooperative behaviors from citizens, bringing direct benefits in terms of organizational image, perceived legitimacy and performance, and favorable policy outcomes (Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006; Riccucci et al., 2014).

Recent research on symbolic representation provides a blueprint for bureaucracies to achieve tangible outcomes through increasing personnel diversity beyond altering bureaucratic behaviors (e.g., Hawes, 2021; Riccucci et al., 2016). And notably, a recent meta-analysis suggested that in general, symbolic and active representation equally promotes organizational performance (Ding et al., 2021). However, with continuous advancement in this research field, divergent evidence has emerged on the extent to which symbolic representation matters, or if its benefits truly exist (Benton, 2020; Lee & Nicholson-Crotty, 2022; Sievert, 2021). Similar to studies of active representation, exploration of symbolic representation highlights the importance of considering contextual conditions, which could largely contribute to the heterogeneity of empirical evidence. To systematically analyze the effect of symbolic representation and how its variation may follow certain meaningful patterns, a meta-analysis of 28 quantitative studies and 286 effect sizes was conducted. A meta-regression analysis further examined how the salience of symbolic representation is influenced by passive representativeness, symbolic outcomes, policy and geographical contexts, and research design.

This meta-analysis contributes to research on symbolic representation in several ways. First, by reviewing research findings from diverse settings, this study identifies whether optimistic expectations for symbolic representation are warranted. Further, this study expands beyond the concept of passive and symbolic representation as one-dimensional constructs and examines the significance of different facets within their complex nature (e.g., passive representation at different organizational levels, citizens' perceptions or behaviors as the outcome of symbolic representation). Moreover, through meta-regression analysis, this study elaborates on the applicability and limitations of symbolic representation by examining whether the observed passive-symbolic representation linkage is moderated by context and research design. Through its substantive findings, this study highlights the importance of moving beyond the yes-or-no dispute that questions, “Does it exist?” and rather asks, “When, and under what conditions, does it matter?” The answers to such questions will thus echo the need for increasing attention dedicated to contextual impacts on representative bureaucracy and contribute to a more refined theoretical exploration of symbolic representation.

2 THEORY OF SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATION

As the “third wave” in representative bureaucracy research, symbolic representation advances the theory by shifting the spotlight from public servants to their citizen counterparts (Bishu & Kennedy, 2020). It argues that “the presence of minority representatives, in and of itself, can change the behavior of the clients and their perceptions about the legitimacy of government” (Gade & Wilkins, 2013, p. 270). Unlike active representation, which stresses active efforts by representative bureaucrats, symbolic representation suggests that no purposeful action by the bureaucratic representatives is required to produce favorable citizens outcomes — “being something” itself, rather than “doing something”, can generate salient benefits (Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006; Theobald & Haider-Markel, 2009). Though empirical investigations on symbolic representation began relatively late, its roots can be traced back to earlier theorists. As Mosher (1968), for example, indicates, “the importance of passive representativeness often resides less in the behaviors of public employees than in the fact that the employees who are there are there at all.”

Drawing on existing literature, two perspectives were mainly adopted to understand the occurrence of symbolic representation and the foundation of its potential positive effects: the “mirror image” perspective and the “institutional symbol of democracy” perspective (Keiser et al., 2022). The “mirror image” perspective emphasizes the individual-level psychological foundation of identity congruence in improving communication, given similar life experiences and shared values (Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006; Roch et al., 2018). It suggests that when bureaucrats mirror the characteristics and values of a particular group, it improves interactions between the bureaucrats and the represented individuals, fostering symbolic representation. In contrast, the “institutional symbol of democracy” view stresses the independent values of democracy conveyed through passive representativeness that are significant for bureaucracy and society as a whole (Mosher, 1968). From this perspective, the symbolic benefits stem from the signals of equity, inclusiveness, and power-sharing embedded in bureaucratic representation. This, in turn, promotes perceived legitimacy and public support (Kittilson & Schwindt-Bayer, 2010; Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006). In essence, the theory of symbolic representation sheds light on the more nuanced or implicit effect of representation, which is, conceptually, independent from the behavioral representativeness of bureaucrats.

Despite evidence supporting the existence of symbolic effects, the debate surrounding symbolic representation is contested. Headley et al.'s (2021) exploratory qualitative research, for example, pointed out that the symbolic benefits of passive representation can be undermined if not accompanied by an organizational commitment to bureaucrats' benevolent treatment of citizens. The authors, therefore, highlighted the significance of considering individual-level experiences and interactions when examining how the presence of bureaucratic representatives shapes citizens' beliefs toward public agencies. Likewise, quantitative studies presented mixed evidence. For instance, an experimental study conducted by Riccucci et al. (2016) identified the causality between passive representation and citizens' willingness to engage in coproduction within a recycling program; However, two replication studies exploring citizen coproduction in emergency preparedness and criminal justice programs found no support for the anticipated symbolic effects (Ryzin et al., 2017; Sievert, 2021), suggesting that symbolic representation can be policy-specific and contingent to context. Therefore, as studies in this area continue to accumulate, it is essential to synthesize existing evidence on symbolic representation, identify potentially relevant contextual conditions under which symbolic effects are more likely to exist, and offer a clearer map for future research.

3 CONTEXT MATTERS: IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL MODERATORS

To fulfill this purpose, the current study examines a series of moderators that indicate the potential manifestation of contextual impacts on the passive-symbolic representation linkage. Specifically, the likely effects of the four substantive (measurement of representativeness, organizational stratification, represented identity, representation outcome), one methodological (research design), and two contextual (policy domain and country of study) moderators on the passive—symbolic representation relationship, were extracted and assessed.

3.1 Measurement of representativeness: Organizational- or individual-level

There are two different measures of representatives that echo the two aforementioned perspectives taken in interpreting the occurrence of symbolic representation, which could be one of the impact factors on observed symbolic effects. On the one hand, research shows that the mere presence of bureaucratic representatives at the organizational level, or say, the fact that a bureaucracy “looks like” the clients it serves in an aggregate sense, can send meaningful signals, thus evoking positive citizen responses (e.g., Baniamin & Jamil, 2023; Breslin, 2019; Riccucci et al., 2014). Relevant studies measure passive representation, which commonly serves as the independent variable, through the demographic composition of the workforce in public agencies either at the frontline (e.g., Baniamin & Jamil, 2023) or in managerial positions (e.g., Dantas et al., 2022). It is important to note that in these contexts, signals of bureaucratic representation are presented as manifestations of the organization's image regarding a representative workforce, rather than individual-level representativeness experienced by citizens in substantive service delivery scenarios.

In contrast, another body of research examines the symbolic effects of one-to-one identity congruence between the client and the bureaucrat during actual interactions (e.g., Guul, 2018; Lee & Nicholson-Crotty, 2022; Theobald & Haider-Markel, 2009). In these studies, the measurement of representativeness is largely dichotomous, indicating whether the individual citizen and bureaucrat share a certain identity (e.g., student and their teacher, driver and the police officer they encountered, etc.). Behind these two different ways of measuring are divergent expectations of how bureaucratic representation works symbolically. That is, whether attitudes for public agencies depends on if the specific government official resembles the individual they interact with, or if the organization passively represents its clients as a whole (Keiser et al., 2022). Therefore, in addition to further theoretical explorations on relevant concepts and mechanisms, it is reasonable and useful to quantitatively examine whether the measurement itself could be a source of inconsistencies of evidence accumulated through the accumulating symbolic representation studies.

3.2 Organizational stratification: Frontline or managerial representation

The symbolic effects of bureaucratic representation might vary from the rank (or, say, the organizational level) at which bureaucratic representatives are present. According to the meta-analysis of Ding et al. (2021) on representative bureaucracy, in which studies on active representation comprised the majority of its sample, representation at the frontline rather than managerial levels results in better organizational outcomes. This may be attributed to the fact that bureaucrat-client encounters happen more often at the street level, where frontline administrators exert immediate and visible influences on policy implementation at their discretion (Meier & Bohte, 2001). Unlike active representation that relies on input from bureaucrats, the theoretical foundation of symbolic representation supposes that a lack of interactivity may not cloud the salience of managerial representation (Lucero et al., 2022). Moreover, with a greater degree of authority and a more powerful voice, managerial representation can be perceived as a stronger signal in demonstrating certain democratic values (Huber & Gunderson, 2023).

Empirically, both frontline and managerial representation have been investigated in studies focused on either organizational or individual-level representativeness. For instance, using a survey experiment, Lucero et al. (2022) showed that identity congruence between an individual citizen and their city manager may increase their compliance with city disaster preparedness orders (i.e., measuring individual-level representativeness, with the bureaucratic representative in a managerial position). Or, utilizing observational data, Wang et al. (2019) examined whether a higher presence of minority police officers would improve citizens' perceived criminal justice (i.e., measuring organizational-level representativeness, with the bureaucratic representatives being front-line officers). However, fewer studies have compared symbolic representation effects across organizational stratifications (e.g., Kang et al., 2022; Xu & Meier, 2021). The question of “Who represents?” has been adequately discussed in the context of research on active representation, but is of equal significance to investigations of symbolic representation—an area of research where it has received comparatively less attention. Hence, this study incorporates organizational stratification as a moderator and assesses the extent to which symbolic effects vary across different ranks of bureaucratic representatives.

3.3 Represented identity: Race, gender, or other

Another potential impact factor on the linkage between passive and symbolic representation is the characteristic on which the measured representativeness is based. While the theory of representative bureaucracy demonstrates concerns for diverse representativeness in its essence (Mosher, 1968), existing empirical studies have predominantly focused on the most prominent demographic characteristics, such as race and gender (Kennedy, 2014). This focus is partially due to data limitations but is also supported by evidence that these identities have the greatest impact on political attitudes and policy perceptions (Keiser et al., 2002; Meier & Jr Stewart, 1992). However, it is acknowledged that restricting the analysis to gender and race might present an incomplete image of representation, as other non-observable characteristics that speak to common experiences and may be central to shared values, could be overlooked (Bishu & Kennedy, 2020; Meier, 2019). To move beyond a narrow operationalization of shared identity, scholars have begun to explore identities beyond race and gender, which can still be salient to the represented population in specific contexts (e.g., LGBTQ status, religion, occupation, etc.). For example, Dantas et al. (2022) offered evidence supporting the symbolic representation effects of the “favela” identity in Brazil, which encompasses the intersectional identity of race, place of birth, and socio-economic status and is more salient than the dynamic of race alone. Therefore, as independent studies increasingly capture broader non-observable and intersectional identities to advance the empirical application of representative bureaucratic theory, it is meaningful to examine whether demographic salience in terms of race and gender still indicates a unique or more substantial effect (Ding et al., 2021).

3.4 Representation outcome: Perceptual or substantive

The potential benefits of symbolic representation have been reported from diverse aspects, which can be categorized as perceptual and substantive outcomes in terms of their forms. Original articulation of symbolic representation stressed its potential to enhance citizens' perceptions and attitudes toward bureaucracies, including but not limited to their satisfaction, perceived legitimacy, trustworthiness, and fairness (e.g., Hibbard et al., 2022; Riccucci et al., 2014). Subsequent studies extended the concept and examined the direct impact of bureaucratic characteristics on citizens' behavioral intentions (e.g., Riccucci et al., 2016), actual behaviors related to compliance or cooperation with organizational decisions (e.g., Lee & Nicholson-Crotty, 2022), and tangible policy outcomes for the represented group (e.g., Wright, 2022). For example, Guul (2018) found that job seekers exhibited higher levels of coproduction effort when matched with a bureaucrat of the same gender. However, it is noted that even perceptual impacts may fall short in certain circumstances (e.g., Benton, 2020; Socia et al., 2021). Therefore, to assess whether focusing on perceptional (attitudes, perceptions, and behavioral intentions) or substantive outcomes (behaviors or tangible policy outcomes) of citizens influenced the strength of the detected linkage between passive and symbolic representation in existing studies, this analysis includes the measurement of representation outcome as a moderator.

3.5 Policy context: Salient or not for the represented identity in question

One of the prerequisites for active representation to occur stipulates that a policy must be salient for the demographic characteristic in question (Meier, 1993). That is, policy implementation shall directly benefit the represented population as a class (Wilkins & Keiser, 2006). For example, a policy issue needs to be “gendered” to anticipate the benefit of promoted gender representation, such as policies geared toward preventing sexual assault or domestic violence (e.g., Atkins & Wilkins, 2013). In terms of race, policy areas such as law enforcement and education are deemed highly significant, especially in countries with a deep history of racial inequality (Darling-Hammond, 1998; Weitzer & Tuch, 2006). Furthermore, certain categories of public services, such as those provided to veterans, may be deemed salient to their specific client groups (Gade & Wilkins, 2013). Nevertheless, research increasingly suggests that the potential of bureaucratic representation may not be exclusive to these “typical” policy areas. For instance, Riccucci et al. (2016) found that female leadership improved citizens' willingness to co-produce, even in a government program that was conventionally not gender-specific: recycling. Comparable evidence on racial representation was also noted in diverse contexts such as emergency management and healthcare (Herman, 2007; Lucero et al., 2022). Given these observations, policy context is included as a moderator to investigate whether stronger symbolic effects still appear in policy domains deemed more relevant to the represented population.

3.6 National context: US or Non-US settings

The literature on representation bureaucracy has primarily focused on a US. context (Bishu & Kennedy, 2020). Responding to the challenge of generalizability, recent scholarship has expanded its geographic coverage in examining multiple aspects of representative bureaucracy theory, including the passive-symbolic representation link (see Doornkamp et al., 2023; Guul, 2018; Sievert, 2021). Particularly, evidence from non-liberal democracies, such as Brazil, China, and Bangladesh, has been on the rise in recent years (see Baniamin & Jamil, 2023; Dantas et al., 2022; Xu & Meier, 2021). Given this advancement, it is worthwhile to ask whether the expected outcomes of symbolic representation vary across US and non-US contexts.

3.7 Research design: Observational or experimental

Besides the abovementioned substantive moderators, this meta-analysis also looks at the extent to which research design matters. Given that the majority of earlier research is based on observational data, the increasing application of experimental frameworks has undoubtedly enriched the understanding of the linkage between bureaucratic representation and its symbolic effects (Riccucci et al., 2014; Riccucci et al., 2018; Schuck et al., 2021). To determine if divergences in research design also account for the variation of findings on symbolic representation, this method indicator is included as an additional moderator.

4 DATA AND METHODS

Commonly referred to as the “analysis of analyses,” meta-analysis is “the statistical analysis of a large collection of analysis results from individual studies for the purpose of integrating the findings” (Glass, 1976, p.3), which explicitly focuses on quantitative research. Initially adopted in medical research, meta-analysis is now frequently used in a range of social science studies. In the field of public administration, in particular, scholars have used meta-analysis to investigate critical topics, including but not limited to bureaucratic representation (Ding et al., 2021), workforce diversity (Ding & Riccucci, 2023), strategic planning (George et al., 2019), performance management (Gerrish, 2016), red tape (George et al., 2021), and citizen satisfaction (Zhang, Chen, et al., 2022).

This meta-analysis was accomplished in five stages: (1) searching the literature and screening for relevant studies; (2) extracting and calculating the effect sizes based on information provided in the original studies; (3) estimating the average effect size to suggest an overall association between passive representation and its symbolic effects; (4) conducting meta-regression and complementary subgroup analysis to explore the sources of variations among studies and effect sizes (i.e., the moderators); (5) checking for potential publication bias.

4.1 Data collection

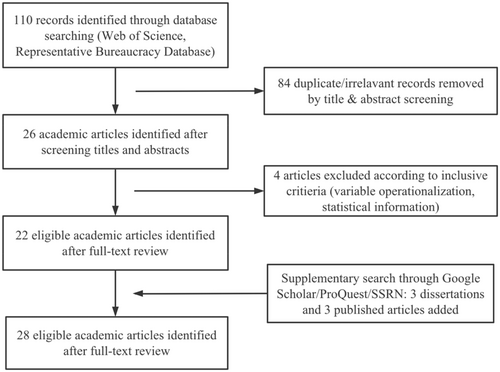

Data collection commenced by using the Web of Science (WoS) SSCI database to search for peer-reviewed journal articles. Search terms such as “symbolic representation,” “symbolic effects of representation,” and “symbolic AND representative bureaucracy” were used in the “topic” field. By limiting the research discipline to “public administration” and then excluding non-English and non-academic articles, the search yielded 70 results as of April 1, 2022. Following previous meta-analyses related to representative bureaucracy (Ding et al., 2021; Ding & Riccucci, 2023), this study utilized the Representative Bureaucracy Research Archive Data Base.1 By filtering for studies tagged with the keywords “symbolic representation,” 40 studies from the database were collected. After removing duplicates from 110 records, abstracts of the studies were screened to exclude qualitative research and studies that did not focus on symbolic bureaucratic representation, which resulted in 26 relevant studies.

To ensure the comprehensiveness of the search, two supplementary searches were conducted. I first used Google Scholar, and paid particular attention to the references of collected relevant articles as well as studies that cited the original article. Through this process, three published studies were deemed relevant (Guul, 2018; Meier & Nicholson-Crotty, 2006; Wang et al., 2019). The second search was performed via ProQuest's Dissertation and Theses Global Database and Social Science Research Network (SSRN), in an attempt to reach “gray studies” that have not been published, and check whether publication bias exists in the research field of symbolic representation. Three eligible dissertations were identified, while no relevant working papers from the SSRN were found.

Once the relevant studies were collected, I performed full-text reviews using the following inclusion criteria to identify primary studies for the meta-analysis: (1) The study conducts a direct quantitative test of the symbolic outcomes of passive bureaucratic representation. (2) Passive representation, as the independent variable, is measured as the proportion of bureaucratic representatives (at the organizational level) or identity congruence between the individual bureaucrats and clients (at the individual level). (3) The dependent variable, that is, the symbolic effect of representation, is operationalized as citizens' perceptual or behavioral responses to representative agencies, or specific policy outcomes. (4) Sufficient statistical information, including but not limited to sample size, t, Z, chi-square, beta values, and p-values, is provided in the study. The refined full-text review yielded 28 acceptable studies comprising the final sample for the meta-analysis, including 25 published and three unpublished studies. Figure 1 depicts the procedures for the literature search and inclusion.

4.2 Coding procedures

I then extracted and documented information from the acceptable studies. Two categories of data were coded in the synthesis: data indicating the effect sizes and data for the moderators.

Referring to established conventions and suggestions from Ringquist (2013), this study used r-based effect sizes to represent the passive representation-symbolic representation effect from original studies. When the correlation coefficient r or the standardized regression coefficient β were not provided, the following equation was used to calculate the r-based effect sizes: (or, if using maximum likelihood models).

The t-scores, if not reported, were calculated via the parameter estimates and standard errors. Following the lead of previous meta-analyses published in top public administration journals (e.g., Lu, 2018; Zhang, Li, & Yang, 2022), when original studies identify statistically significant parameter estimates using asterisks or p-values only, I set the t-score equal to the value of t at the symbol threshold and given degrees of freedom. Insignificant coefficients with no additional information were coded as an effect size of zero.

For the studies employing tests of means or analysis of variance (ANOVA) only, group difference-based effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated and then converted into r-based effect sizes. For the studies estimating probit or logit models, I first recorded the odds-based effect sizes and then transformed them into r-based effect sizes. For experimental studies performing both mean comparisons and regressions, the regression results were adopted. Further, Fisher's r-to-Z transformation was conducted to remedy the slight downward bias of the r estimate. The formulas of transformation are as follows: , with variance .

Drawing on the suggestion of Ringquist (2013, p. 73), when an original study reports multiple effect sizes, mostly due to different model specifications or sample restrictions, all relevant effect sizes were coded to maintain within-study variation. Finally, a total of 286 effect sizes were drawn from 28 primary studies. Several articles, however, did include multiple independent samples within a single research (mainly from different periods or countries). Therefore, 32 independent samples were identified from the 28 studies, with separate effect sizes distinguished by year or country (Baniamin & Jamil, 2023; Benton, 2020).

In light of the potential sources of variations for the passive-symbolic representation link, four substantive, one methodological, and two contextual indicators were generated for the meta-regression. Details of the coding rules for the moderators are included in Table 1. Table A1 presents an overview of the distribution of the primary study descriptors for all 28 studies.

| Moderator | Measurements |

|---|---|

| Measurement of representativeness | If measuring the representation at the individual level, I coded it as 1; 0 if at the organizational level. |

| Organizational stratification | If focusing on managerial-level bureaucratic representation, I coded it as 1; 0 if focusing on the frontline representation. |

| Represented identity | |

| Race | If focusing on racial representation, I coded it as 1; 0 otherwise. |

| Gender | If focusing on gender representation, I coded it as 1; 0 otherwise. |

| Other identities | If focusing on representation based on identities other than race and gender, I coded it as 1; 0 otherwise. |

| Representation outcome | If measuring the representation outcomes as substantive behaviors or other tangible citizens/policy outcomes, I coded it as 1; 0 if measuring as “perceptual” outcomes, including attitudes, perceptions, and behavioral intentions. |

| Policy domain | If the policy context is conventionally less salient to representative bureaucracy, I coded it as 1; 0 if generally recognized as highly salient. |

| Country of study | If analyzing data from non-US countries, I coded it as 1; 0 if using the US data. |

| Research design | If adopting an experimental design, I coded it as 1; 0 if using observational data. |

5 ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

The 286 effect sizes indicating the correlation between passive and symbolic representation range from −0.329 to 0.433. Among all the individual effect sizes, more than half (n = 172) demonstrated a positive correlation, supporting the existence of the symbolic benefits of passive representation. Meanwhile, there were 98 effect sizes implying a negative association and highlighting the need to further investigate the complexity of symbolic representation. The remaining 16 effect sizes reported null association.

5.1 Population effect size

A random-effects model was employed to pool the 286 effect sizes given its more applicable assumptions and greater external validity (Hedges & Vevea, 1998; Ringquist, 2013), which was also supported by effect-size heterogeneity tests. A Q-test was first conducted to test the null hypothesis that variance in observed effect sizes is solely caused by sampling error. Since the Q statistic was 2153.97 with a p-value smaller than 0.001, the null hypothesis was rejected. Moreover, the I2 statistic of 86.8% indicates a fairly high heterogeneity across effect sizes. Both tests justified the adoption of the random-effects model for integrating effect sizes, and implied that meta-regression is needed to untangle the potentially patterned variations.

Notably, most primary studies generated more than one effect size; the effect sizes in this meta-analysis are thus not independent but adhere to a nested structure. Therefore, a three-level random-effects model was fitted to better capture these dependencies while pooling the effect sizes (Cheung, 2014),2 using the R package metafor. Based on the model, the weighted average effect size in Fisher's z was calculated as 0.062 (t = 3.96, p < 0.001), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.031, 0.093]. As a suboptimal strategy, I aggregated the effect sizes by sample and re-ran the conventional random-effects analysis, yielding a population effect size of 0.060 (t = 3.48, p < 0.01), with a 95% confidence interval of [0.025, 0.095]. Table 2 presents the meta-analysis results at the effect and sample levels. Despite the small magnitude of correlation, the consistent results in both cases suggest a positive association between passive representation and symbolic representation. That is, the results empirically support the significance of symbolic representation, suggesting that passive bureaucratic representation can result in overall favorable outcomes.

| Level of analysis | No. of effect sizes | Population effect size | 95% CI | Q | I2 | τ2 | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect (three-level model) | 286 | 0.062 | [0.031, 0.093] | 2153.97*** | 91.8% | 0.0069 (sample) 0.0031 (effect) | 3.96*** |

| Sample | 32 | 0.060 | [0.025, 0.095] | 419.90*** | 92.6% | 0.0088 | 3.48** |

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

5.2 Moderator analysis: Meta-regression

A meta-regression analysis was then implemented to examine whether the variations in the collected effect sizes could be explained by the moderators previously identified. Table 3 provides the results of the meta-regression analysis, with random effects assigned to the sample level as the grouping factor. A cluster-robust test was also conducted using a sandwich-type estimator to generate robust variance estimations of the model coefficients. Model 1 includes all the identified moderators. Model 2 introduces the source of the study to check if publication bias exists, which is elaborated upon in the next section of this article.

| Moderator | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Individual-level representation (ref. = organizational-level measure) | −0.051 (0.044) | −0.050 (0.044) |

| Managerial representation (ref. = frontline representation) | −0.131* (0.049) | −0.131* (0.050) |

| Types of represented identity (ref. = other) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.042 (0.085) | −0.037 (0.093) |

| Gender | −0.085 (0.086) | −0.081 (0.094) |

Substantive measure of outcome (ref. = perceptual outcome) |

0.051 (0.069) | 0.070 (0.083) |

Low identity salience of the policy area (ref. = highly salient) |

0.007 (0.045) | 0.011 (0.043) |

Non-US data (ref. = US data) |

0.021 (0.049) | 0.012 (0.055) |

Observational study (ref. = experimental) |

−0.088† (0.049) | −0.092† (0.053) |

| Published study (ref. = non-published) | 0.081 (0.093) | |

| Constant | 0.189* (0.090) | 0.107* (0.123) |

| No. of clusters | 31 | 31 |

| No. of effect sizes | 285 | 285 |

| AIC/BICa | −221.04/−184.84 | −219.55/−179.77 |

| F statistics | 11.75*** | 10.27*** |

- Note: Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses. One of the studies does not specify the policy context explicitly (Rombalsky, 2010), resulting in a missing value in the policy-relevance moderator and a final N of 285 effect sizes. The results of a robustness check involving this study without a policy-relevance indicator are provided in the appendix (see Table A3).

- a The Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) instead of pseudo-R-square are used to compare the fit of different multi-level meta-regression models (Baguley, 2018; Harrer et al., 2021). Models with lower AIC/BIC values are a better fit with less information loss.

- † p < 0.1.

- * p < 0.05.

- *** p < 0.001.

Additionally, subgroup analysis based on the above moderators was conducted through multi-level meta-analysis as an additional reference (see Table A2). The average effect sizes from all subcategories were found to be positive, though they were not equally significant in a statistical sense.

As shown in both regression models, the symbolic effects of managerial representation appear less robust than that of frontline-level representation (β = −0.13, p < 0.05). This result implies that given the effect sizes detected by existing research designs, stronger responses from citizens are found to the presence of bureaucratic representatives at the street level rather than the managerial positions. A significant effect was also found on the methodological moderator. The observed passive-symbolic representation link turned out to be weaker in observational studies than in the studies that adopted experimental designs (β = −0.092, p < 0.1). With a sub-group aggregate effect estimate of 0.082 (see Table A2), the experimental studies, which contribute 127 effect sizes from 12 samples, reported a more substantial symbolic effect of passive representation than their observational counterparts.

Results for the rest of the moderators suggest no significant impact of these factors on the observed passive-symbolic representation linkage. Regardless of whether the passive representation is operationalized as aggregate proportions of representative bureaucrats or one-to-one identity congruence, it does not significantly moderate the salience of symbolic representation. At the same time, there is no evidence that the representativeness of race or gender resulted in greater symbolic effects than other types of identities that are involved in the current sample studies, such as profession, immigrant status or local identity. In addition, whether the representation outcomes were measured by substantive behaviors and policy outcomes on the client side, or their attitudes and perceptual changes, makes no significant difference in terms of the symbolic effects.3 Moreover, symbolic representation may offer invaluable insight even in policy contexts that do not typically emphasize representation issues (like environmental protection or emergency management). Finally, the research location itself does not seem to matter with regard to untangling the myth of symbolic representation. Given the insignificant coefficients, the observed strength of symbolic representation does not vary much among the US and non-US countries.

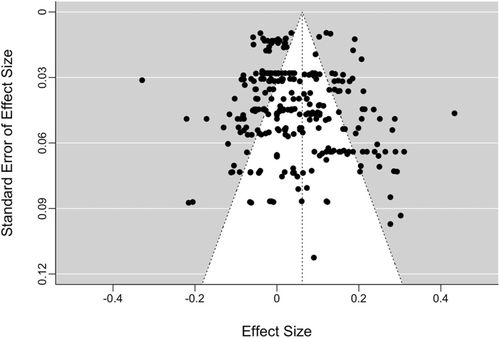

5.3 Publication bias

Publication bias occurs when the probability of a study getting published is affected by its results (Rothstein et al., 2005). Given the potential threat of a distorted sample to the validity of effect estimates, tests for publication bias are necessary for meta-analysis. In the present study, I first drew a funnel plot to visually check the distribution of observed effect sizes (see Figure 2), by which the value of all 286 effects (the X-axis) and their standard error (the Y-axis) are displayed. With no publication bias, the data points in such a plot should form an approximately symmetrical, upside-down funnel. It may be noted that, for the most part, the figure points toward rough symmetry and does not present a pattern that would be evident of public bias (Zhang, Chen, et al., 2022). However, several effect sizes fell out of the ideal limits, and apparent outliers remain, suggesting the need to examine the observed funnel symmetry statistically.

I then conducted Egger's regression test (Egger et al., 1997),4 with the results listed in Table 4. As noted in the table, the estimate of the intercept does not significantly differ from zero at a 95% confidence level (p > 0.05), which provides insufficient support for funnel plot asymmetry or the existence of publication bias. An additional test that takes the sample sizes of studies into account by using the square root of the sample size as a measure of precision (Zhang, Li, & Yang, 2022)5 generated results that were nearly identical to those of Egger's test. Finally, as shown in the meta-regression model 2, which includes the indicator of published study, the corresponding coefficient was proven insignificant. Taken together, given a high degree of effect size heterogeneity and the results of multiple tests, publication bias is not a major threat in the present meta-analysis.

| Coefficient for | Estimate (standard error) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Egger's test | |||

| Intercept | 0.501 (0.298) | 1.683 | 0.094 |

| Inverse standard errors | 0.019 (0.009) | 2.191 | 0.029* |

| SQR sample size test | |||

| Intercept | 0.499 (0.299) | 1.671 | 0.096 |

| SQR of sample size | 0.019 (0.009) | 2.192 | 0.029* |

- Note: Standard errors of the regression coefficients are provided in the parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

6 DISCUSSION: DOES SYMBOLIC REPRESENTATION MATTER?

The symbolic essence of representation has long been a concern, but it was not until the last two decades that the link between passive representation and its direct symbolic outcomes was empirically tested. Although supportive evidence for symbolic representation was widely reported across diverse policy domains, disputes regarding its limits arose (Benton, 2020; Headley et al., 2021). To elucidate the complex nature of symbolic representation, this meta-analysis synthesized the results of existing quantitative studies, and explored moderators that construct a panorama of the passive-symbolic representation linkage. Pooling 286 effect sizes from 28 eligible studies, this meta-analysis reveals a statistically significant, albeit weak, association between passive bureaucratic representation and favorable responses from citizens. This result echoes a previous meta-analysis on representative bureaucracy, in which Ding et al. (2021) highlight the equally important role of symbolic representation in enhancing organizational performance compared to active representation, which relies on the direct engagement of bureaucratic representatives. Meanwhile, given the highly heterogeneous effect sizes, the multi-dimensional findings from the meta-regression shed further light on possible sources of variation in the passive-symbolic representation link, which provides meaningful implications for future research.

First, given the different contributions of observational and experimental studies to the field, more attention on research design is required to advance the study of symbolic representation. Survey experiments represent the primary type of experimental design used in relevant research. Though relying on hypothetical scenarios, a randomized experimental design demonstrates distinct advantages for identifying causal relations with relatively high internal validity (Bouwman & Grimmelikhuijsen, 2016). It enables scholars to directly measure citizens' responses to different types or levels of bureaucratic representation, with potential confounding factors such as bureaucratic behaviors remaining well-controlled (Schuck et al., 2021). In this sense, the larger effect sizes observed in experimental studies further prove that symbolic representation does matter and has a solid empirical foundation.

However, experiments on symbolic representation have certain limits. Passive representation as the independent variable is largely measured at the organizational level (e.g., Baniamin & Jamil, 2023; Riccucci et al., 2014), leaving the individual-level mechanism of how identity congruence shapes citizens' reactions understudied (Guul, 2018). That is to say, there is still a gap between the halo effect of a representative institution and people's views toward the individual bureaucrats they interact with (Lee & Nicholson-Crotty, 2022). Research using micro-level observational data adds this critical piece to the jigsaw of symbolic representation (e.g., Gade & Wilkins, 2013; Keiser et al., 2022; Theobald & Haider-Markel, 2009), while the classical challenge of “correlation or causation” facing the observational camp needs to be handled with more rigorous statistical inference to separate the “symbolic part” of observed citizen outcomes.

Given the above observations, it is crucial to acknowledge the value of both methodological frameworks, while being mindful of the conceptual operationalizations embedded within the two types of research designs. Expanding the research agenda for both camps is necessary to achieve comparable results across different methodological investigations. For example, additional experiments focusing on individual-level symbolic representation effects could be conducted. Also, replicating the existing experiments and introducing diverse outcome measures would help identify the potential boundaries of symbolic impacts. For observational studies, further efforts may wish to determine whether tangible citizen outcomes were indeed attributable to symbolic representation, or if they were generated during more complex bureaucrat-citizen interactions (Headley et al.'s, 2021). Multiple explorations, including but not limited to enriching data sources (e.g., Guul, 2018) and introducing qualitative perspectives (e.g., Xu & Meier, 2021), could be a meaningful way to obtain more precise knowledge of symbolic representation.

Second, more potent effects of bureaucratic representation are observed at the frontline compared with managerial levels, given the accomplished studies. It is understandable that with the exercise of discretionary authority, frontline workers actively shape de facto policy implementation (Andrews et al., 2014; Lipsky, 2010). Therefore, the identity of the street-level bureaucrats who directly handle service delivery and work with the social groups they represent, tends to affect citizens in a more direct and intuitive manner (Kang et al., 2022). Such a clue might also help interpret research findings based on inter-governmental comparisons (Park & Mwihambi, 2022), considering the insights of Ryzin et al. (2017) that weaker trust and reduced citizen responsiveness to a request from federal agencies is more often expected when compared to similar interactions with the local government. However, it is vital to reiterate the significance of contexts for symbolic representation. The operationalization of representativeness varies across studies conducted in different institutional and cultural contexts, which could influence the detected effects of symbolic representation at different organizational levels. Additionally, it is anticipated that the effects of managerial representation are not limited to citizen responses but can also impact the attitudes and behaviors of lower-level bureaucrats within an organization. These more implicit symbolic effects, however, are rarely captured in existing research. Therefore, additional evidence from studies focusing on hierarchical differences of symbolic representation within coherent contexts of country and policy area is needed to reach more robust conclusions.

Third, while no significant moderating effects were found regarding the other substantive moderators, these results help deepen the understanding of symbolic representation in multiple ways. For example, though merely “being something” without “doing something” (Pitkin, 1967), passive representation has the potential to not only improve citizens' attitudes but change their behaviors and result in tangible policy outcomes (Breslin, 2019; Doornkamp et al., 2023; Guul, 2018; Herman, 2007; Wright, 2022). Moreover, instead of emphasizing the significance of demographics like race or gender, this meta-analysis shows that those more implicit characteristics and intersectional identities, such as professions and community identities, may work equally well as representative “symbols” (Dantas et al., 2022; Gade & Wilkins, 2013; Hawes, 2021). This finding prompts us to reflect on the conventional narrow application of identification and to actively explore representativeness based on intersectionality, which could begin with qualitative case studies and analyses of the combination of a modest number of identities (Meier, 2019). Meanwhile, it is further noted that the simplified and predominantly adopted dichotomy regarding concepts such as race and gender overlooks the constructed nature of identities and contextual nuances, thereby limiting the theory (Bishu & Kennedy, 2020; Strader et al., 2023). Hence, this study calls for more refined examinations of contextual conditions under which specific identities are uniquely structured and may effectively “represent as a symbol.”

Fourth, it is worth mentioning that given that less significant effects were not found within non-US contexts, generalizing the symbolic representation theory in terms of institutional settings is off to a promising start. The narrative of representation bureaucracy research has long been limited to the United States. Nevertheless, more recent efforts in both active and symbolic representation research demonstrate its relevance not only to a broader range of Western democracies (e.g., Doornkamp et al., 2023) but also to developing countries with hierarchical social structures and conservative traditions (e.g., Dantas et al., 2022). This finding suggests that even in a context where minority groups experience systematic inequality, symbolic representation can transcend window-dressing and lead to identifiable benefits. For example, Baniamin and Jamil (2023) found that in patriarchal societies like Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, equal gender representation significantly enhanced how citizens perceived the performance and fairness of a fictitious committee for controlling violence against women.

In addition to offering directions for future research that will enrich methodological and theoretical investigations, the results of this meta-analysis hold valuable implications for real-world bureaucratic practice. It supports the notion that both promoting a representative organizational image and strategically managing direct interactions with clients with different identities will be beneficial. And given that positive outcomes may be expected with respect to not only policy issues that conventionally emphasize representation, this study encourages practitioners from a wide range of fields to consider symbolic representation in their agenda of personnel arrangement as well as policy implementation.

While this study provides meaningful implications, it is necessary to acknowledge its limitations. First, the focus on the linear relationship between passive representation and its symbolic effects limits the inclusion of interactive effects found in comparable studies (e.g., Lucero et al., 2022; Roch et al., 2018). Examining the moderating effects of representation on other empirical links may offer additional perspectives on symbolic representation in broader contexts. However, due to the diversity and specificity of these links, it was not feasible to integrate them into the present analysis. Secondly, the current measurements of moderators may fail to capture more nuanced within-level differences. For instance, the realities of bureaucratic representation in non-US countries, with their diverse demographic structures and political institutions, can significantly vary and impact both the original research design and the strength of correlations observed in this meta-analysis. Further, there are other factors with the potential to impact the passive-symbolic representation linkage that have not been included due to limited observations. For example, one of the critical insights provided by a group of experiments examining how representation boosts coproduction (or fails to) is that the symbolic benefits could be washed out if the projects were too demanding for the public. Representation works for recycling (Riccucci et al., 2016), but not necessarily for blood donation or supporting prisoners' reintegration into society (Ryzin et al., 2017; Sievert, 2021). Last, concerns by qualitative work (such as Headley et al.'s, 2021) cannot be well addressed in the current meta-analysis, while they play an irreplaceable role in understanding symbolic effects in the everyday experiences of citizens. Hence, to obtain more profound and comprehensive knowledge of symbolic representation, more qualitative and mixed-method research would provide important insights.

7 CONCLUSION

In so much as passive representation itself is a symbolic manifestation of the inclusivity and openness of government processes (Headley et al.'s, 2021), symbolic representation has been a concern within the literature on representative bureaucracy since its inception. However, null findings observed in recent empirical investigations questioned the independence of the concept of symbolic representation and called for greater attention to the limits of its actual effects. By aggregating existing empirical evidence on symbolic representation and exploring potential sources of variation, this meta-analysis expects for symbolic representation to bring independent benefits. Valuable insights were provided based on the variations observed for the passive-symbolic representation linkage across multiple moderators. Despite a few limitations, this meta-analysis points to avenues for further research, and advances knowledge on and the practice of representative bureaucracy, with a particular emphasis on its symbolic facet. Importantly, contexts matter a lot to symbolic representation. In practice, insights from the independent study with its very unique background of design, shall also be valued when considering further policy implications of the results based on this meta-analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks the editors and the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. The author is grateful to Richard M. Walker and Bert George for their invaluable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript, and to Nicolai Petrovsky, Jiasheng Zhang, and Jiahuan Lu for their helpful advice on the research methodology.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Endnotes

APPENDIX A

| Author (year) | Country | Research type | Representation type | Sample size | Measure of representation | Level of representation | Outcome measure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baniamin & Jamil (2023) | Multiple countries | Experiment | Gender | 2740; 2254; 1244 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Benton (2020) | United States | Observational | Race | 3919; 4944 | Individual | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Breslin (2019) | United States | Observational | Gender | 434 | Organizational | Frontline | Substantive |

| Dantas et al. (2022) | Brazil | Experiment | Other | 247 | Organizational | Managerial | Perceptual |

| Doornkamp et al. (2023) | Netherland | Observational | Gender | 329 | Individual | Frontline | Substantive |

| Gade and Wilkins (2013) | United States | Observational | Other | 1233 | Individual | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Guul (2018) | Denmark | Observational | Gender | 476 | Individual | Frontline | Substantive |

| Hawes (2021) | United States | Observational | Other | 1067 | Organizational | Frontline | Substantive |

| Herman (2007) | United States | Observational | Race | 16,496 | Individual | Frontline | Substantive |

| Hibbard et al. (2022) | United States | Observational | Gender and race | 1307 | Individual | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Kang et al. (2022) | United States | Observational | Race | 637 | Organizational | Managerial & frontline | Substantive |

| Keiser et al. (2022) | United States | Observational | Race | 5750 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Lee & Nicholson-Crotty (2022) | United States | Observational | Race | 6771 | Individual | Frontline | Substantive |

| Lucero et al. (2022) | United States | Experiment | Race | 1435 | Organizational | Managerial | Perceptual |

| Meier and Nicholson-Crotty (2006) | United States | Observational | Gender | 467 | Organizational | Frontline | Substantive |

| Riccucci et al. (2018) | United States | Experiment | Race | 840 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Riccucci et al. (2014) | United States | Experiment | Gender | 789 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Riccucci et al. (2016) | United States | Experiment | Gender | 733 | Organizational | Managerial | Perceptual |

| Roch et al. (2018) | United States | Observational | Race | 801; 1262 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Rombalsky (2010) | United States | Observational | Race | 10,060 | Organizational | Managerial & frontline | Perceptual |

| Schuck et al. (2021) | United States | Experiment | Gender | 359 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Sievert (2021) | Germany | Experiment | Gender | 1000 | Organizational | Managerial & frontline | Perceptual |

| Socia et al. (2021) | United States | Observational | Race | 994 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Theobald & Haider-Markel (2009) | United States | Observational | Race | 6817 | Individual | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Ryzin et al. (2017) | United States | Experiment | Gender | 604 | Organizational | Managerial | Perceptual |

| Wang et al. (2019) | United States | Observational | Race | 1213 | Organizational | Frontline | Perceptual |

| Wright (2022) | United States | Observational | Gender | 548 | Organizational | Frontline | Substantive |

| Xu and Meier (2021) | China | Observational | Gender | 10,939 | Individual | Managerial & frontline | Substantive |

| Grouping variable | No. of effect sizes | No. of clusters | Pooled effect size | 95% CI | Q | τ2 (sample-level) | τ2 (effect-level) | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-level measure | 66 | 10 | 0.024 | [−0.011, 0.059] | 979.38*** | 0.0016 | 0.0064 | 1.36 |

| Organizational-level measure | 220 | 22 | 0.082 | [0.039, 0.125] | 1174.28*** | 0.0098 | 0.0016 | 3.76*** |

| Frontline representation | 222 | 28 | 0.066 | [0.032, 0.100] | 1863.28*** | 0.0072 | 0.0034 | 3.87*** |

| Managerial representation | 64 | 6 | 0.030 | [−0.040, 0.101] | 223.27*** | 0.0072 | 0.0001 | 0.86 |

| Race representation | 104 | 14 | 0.032 | [0.000, 0.064] | 1091.90*** | 0.0024 | 0.0061 | 2.00* |

| Gender representation | 152 | 16 | 0.081 | [0.026, 0.136] | 868.58*** | 0.0119 | 0.0015 | 2.90** |

| Other-type representation | 30 | 3 | 0.094 | [−0.029, 0.216] | 167.25*** | 0.0104 | 0.0011 | 1.56 |

| Perceptional outcomes | 196 | 22 | 0.067 | [0.035, 0.099] | 998.85*** | 0.0054 | 0.0009 | 4.12*** |

| Attitudes/Perceptions | 133 | 18 | 0.082 | [0.046, 0.118] | 877.18*** | 0.0054 | 0.0014 | 4.48*** |

| Behavioral intentions | 63 | 6 | 0.026 | [−0.032, 0.084] | 98.11 | 0.0046 | 0.0000 | 0.90 |

| Substantive outcomes | 90 | 10 | 0.051 | [−0.021, 0.122] | 1155.03*** | 0.0114 | 0.0065 | 1.40 |

| Citizen behaviors | 58 | 7 | 0.054 | [−0.051, 0.160] | 752.47*** | 0.0174 | 0.0067 | 1.03 |

| Direct policy outcomes | 32 | 3 | 0.053 | [−0.059, 0.165] | 397.28*** | 0.0081 | 0.0056 | 0.96 |

| Policy relevance-high | 187 | 23 | 0.069 | [0.028, 0.110] | 1433.09*** | 0.0091 | 0.0028 | 3.34*** |

| Policy relevance-low | 98 | 8 | 0.035 | [−0.006, 0.076] | 615.76*** | 0.0027 | 0.0035 | 1.72† |

| US context | 196 | 23 | 0.053 | [0.016, 0.089] | 1510.02*** | 0.0068 | 0.0037 | 2.85** |

| Non-US context | 90 | 9 | 0.084 | [0.028, 0.140] | 611.04*** | 0.0065 | 0.0020 | 2.98** |

| Observational study | 159 | 20 | 0.049 | [0.009, 0.088] | 1576.02*** | 0.0069 | 0.0036 | 2.44* |

| Experimental study | 127 | 12 | 0.082 | [0.035, 0.130] | 535.84*** | 0.0064 | 0.0022 | 3.41*** |

- † p < 0.1.

- * p < 0.05.

- ** p < 0.01.

- *** p < 0.001.

| Moderator | Model |

|---|---|

Individual-level representation (ref. = organizational-level) |

−0.056 (0.044) |

Managerial representation (ref. = frontline representation) |

−0.131* (0.049) |

| Types of represented identity (ref. = other) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.035 (0.085) |

| Gender | −0.078 (0.086) |

| Substantive measure of outcome (ref. = perceptual outcome) | 0.049 (0.068) |

| Non-US data (ref. = US data) | 0.018 (0.046) |

| Observational study (ref. = experimental) | −0.080† (0.045) |

| Published study (ref. = non-published) | 0.024 (0.076) |

| Constant | 0.163* (0.114) |

| No. of clusters | 32 |

| No. of effect sizes | 286 |

| AIC/BIC | −222.99/−186.75 |

| F statistics | 11.68*** |

- Note: Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses.

- † p < 0.1.

- * p < 0.05.

- *** p < 0.001.

| Moderator | Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|---|

Individual-level representation (ref. = organizational-level) |

−0.058 (0.046) | −0.51 (0.045) |

Managerial representation (ref. = frontline representation) |

−0.131* (0.051) | −0.131* (0.053) |

| Types of represented identity (ref. = other) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | −0.040 (0.090) | −0.039 (0.099) |

| Gender | −0.083 (0.091) | −0.083 (0.101) |

| Substantive measure of outcome (ref. = attitudes) | ||

| Behavioral intentions | 0.003 (0.095) | 0.001 (0.105) |

| Behaviors | 0.041 (0.087) | 0.066 (0.108) |

| Direct policy outcomes | 0.074 (0.064) | 0.081 (0.069) |

Low identity salience of the policy area (ref. = highly salient) |

— | 0.010 (0.062) |

| Non-US data (ref. = US data) | 0.012 (0.053) | 0.009 (0.056) |

| Observational study (ref. = experimental) | −0.082 (0.069) | −0.093 (0.068) |

| Published study (ref. = non-published) | 0.017 (0.088) | 0.076 (0.120) |

| Constant | 0.177 (0.139) | 0.115 (0.158) |

| No. of clusters | 32 | 31 |

| No. of effect sizes | 286 | 285 |

| AIC/BIC | −215.90/−172.50 | −212.07/−165.15 |

| F statistics | 10.79*** | 9.10*** |

- Note: Clustered robust standard errors in parentheses.

- * p < 0.05.

- *** p < 0.001.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.