Public sector creativity as the origin of public sector innovation: A taxonomy and future research agenda

Abstract

enThis systematic literature review analyses how public servants apply workplace creativity to come up with ideas for public sector innovations, defining public sector creativity and analyzing its practices, features, trends, and hiatuses in knowledge for which we provide a future research agenda. Creativity is the origin of innovation. Public sector creativity, however, is theoretically undefined and underexamined, resulting in unclarity on what constitutes public sector creativity. We define public sector creativity as “public servants coming up with novel and useful ideas through various practices.” Our findings indicate that public servants apply at least six taxonomically distinctive creative practices, and although they are involved to different extent in generating the initial idea and thus do not always generate ideas autonomously, they are creative in finding alternative ways to come up with ideas. However, our review indicates hiatuses in knowledge on public sector creativity, for which we provide a future research agenda.

Abstract

nlDit systematisch literatuuronderzoek analyseert hoe ambtenaren creativiteit toepassen om op ideeën voor innovaties in de publieke sector te komen, definieert creativiteit in de publieke sector en analyseert de werkwijzen, eigenschappen, trends en kennishiaten waarvoor we een onderzoeksagenda opstellen. Creativiteit is de oorsprong van innovatie. Creativiteit in de publieke sector, echter, is theoretisch gezien ongedefinieerd en onderbelicht, resulterende in onduidelijkheid wat creativiteit in de publieke sector inhoudt. Wij definiëren creativiteit in de publieke sector als “ambtenaren die op nieuwe en bruikbare ideeën komen door middel van verscheidene werkwijzen.” Onze bevindingen tonen dat ambtenaren minimaal zes taxonomisch verschillende creatieve werkwijzen toepassen, en ondanks dat zij in verschillende mate betrokken zijn bij het genereren van ideeën en daarmee deze niet altijd autonoom genereren, zijn zij creatief in het vinden van alternatieve manieren om op ideeën te komen. Echter, ons onderzoek toont kennishiaten betreffende creativiteit in de publieke sector, waarvoor wij een onderzoeksagenda opstellen.

Workplace creativity is the origin of organizational innovation (Amabile, 1996) and therefore perceived as critically important for organizations' performance (Mumford et al., 2012; Puccio & Cabra, 2010). As innovativeness of public organizations is regarded essential for providing optimal public services (De Vries et al., 2016; Wynen et al., 2014), focus on workplace creativity is growing in the public sector, illustrated by public sector organizations increasingly being granted managerial freedom to be more creative (Overman & Van Thiel, 2016; Van Thiel, 2001; Wynen et al., 2014) and increasingly expressing their wish to recruit creative public servants (Kruyen et al., 2019; Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2020).

Despite this acknowledgement, it remains unclear what public sector creativity encompasses and how public servants come up with ideas for public sector innovations. Available literature—including previous literature reviews (Anderson et al., 2014; Woodman et al., 1993)—focus either on public sector innovation (De Vries et al., 2016) or workplace creativity within the private sector (e.g., Amabile & Kramer, 2011; Andriopoulos, 2001; Mumford, 2012; Puccio & Cabra, 2010; Zhou & Hoever, 2014). Only a handful of studies focus on workplace creativity in public organizations (e.g., Denhardt et al., 2013; Feeney & DeHart-Davis, 2009; Heinzen, 1994; Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017; Rangarajan, 2008; Visser & Kruyen, 2021) with no systematic analysis of how public servants come up with creative ideas. This is problematic for two reasons.

First, public sector creativity and public sector innovation are analytically distinct concepts and by no means identical (Anderson et al., 2014). Workplace creativity specifically regards the crucial front-end of the innovation process (Amabile, 1996) that has received little to no academic scrutinization compared to other stages of the public sector innovation process (Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017). Indeed, the creativity stage of the public sector innovations process remains largely unexplored leading to a hiatus in knowledge on the origin of public sector innovations.

Secondly, one cannot simply generalize definitions and findings of research into private sector creativity and assume that they apply to public sector. The small body of research on public sector creativity (Denhardt et al., 2013; Feeney & DeHart-Davis, 2009; Heinzen, 1994; Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017; Rangarajan, 2008) and literature on public sector innovation (Pots & Kastelle, 2010; Nählinder, 2013; Bysted & Jespersen, 2013) indicate that public sector creativity likely differs from its private sector counterparts. Most notably, relevant differences encompass reduced and asymmetric creativity incentives for creativity due to little market competition (Borins, 2000; Chen & Bozeman, 2014), an absence of venture capital to seed creativity (Borins, 2000; Chen & Bozeman, 2014), red-tape limiting creative endeavors (Bozeman & Feeney, 2011), strong political interference limiting the ability of long-term planning (Chen & Bozeman, 2014), and adverse selection by creative individuals against public careers (Borins, 2000). The public sector, in short, appears typical in terms of workplace creativity. Research on public sector creativity is necessary to clarify what encompasses public sector creativity, how public servants come up with ideas for innovations, and what hiatuses in knowledge remain.

This systematic literature review aims to analyze the literature for public sector creativity. By doing so, our study will (1) define public sector creativity, (2) provide a taxonomy of the creative practices public servants apply, (3) analyze its idiosyncratic features and trends as covered within the literature, and (4) offer a future research agenda based on identified hiatuses.

“How do public servants apply creativity to come up with ideas for public sector innovations and what hiatuses on knowledge remain on the subject, based on research published in international refereed journal articles and book chapters regarding public services published in the period between January 2000 and March 2020?”

Based on our findings, we define public sector creativity as “public servants coming up with novel and useful ideas through various practices.” Our findings indicate that public servants apply at least six taxonomically distinctive creative practices, and although they are involved to different extent in generating the initial idea and thus do not always generate ideas autonomously, they are creative in finding alternative ways to come up with ideas. However, our review indicates hiatuses in knowledge on public sector creativity, for which we provide a substantive and methodological research agenda.

The article is organized as follows. We start with a theoretical discussion of workplace creativity to delineate the focus of our research and provide a theoretical basis. We then turn to the discussion of the review procedure. Next, we present our taxonomy of practices for public sector creativity, followed by a discussion of its idiosyncratic features and trends. Finally, we offer a future research agenda for public sector creativity based on the identified hiatuses in knowledge, ending with a summary of our key findings.

1 THEORY

Creativity is a pluralist research topic gaining attention from multiple disciplines offering varying definitions such as “Any act, idea, or product that changes an existing domain, or that transforms and existing domain into a new one” or “The production of high quality, original, and elegant solutions to problems,” among others (Csikszentmihalyi, 2013, p. 28; Mumford et al., 2012, p. 4; Kozebelt et al., 2010; Niu & Sternberg, 2001). While Public Administration literature features little research on creativity within public organizations, disciplines as Organizational Sciences and Business Administration/Management have extensively focused on creativity within other types of organizations. The focus of this body of research is on “workplace creativity” defined as “employees coming up with novel and useful work-related ideas” (Amabile et al., 1996, p. 1155). Henceforth, we refer to “workplace creativity” when mentioning creativity.

To delineate: creativity is not synonymous to innovation. Creativity is the origin of organizational innovation and the first stage of the innovation process. Accordingly, creativity is described as the “crucial frond-end of the innovation process” (Amabile, 1996). What sets creativity apart from innovation is that the former typically encompasses the stage of idea generation while the latter also encompasses subsequent processes of social evaluation and practical implementation (Anderson et al., 2014; Amabile et al., 1996; Csikszentmihalyi, 2013). The focus of our research is on the creativity stage as our aim is to analyze how public servants come up with ideas for public sector innovations.

To clarify the focus of our research, we dissect the definition of workplace creativity and elaborate on its key elements. First, the element of “coming up with” refers to either passive creative appearances or active creative practices that result in employees introducing ideas, which is a result of the interaction of personal, process, environmental, and leadership factors (Puccio & Cabra, 2010; Wallas, 2014). These creative practices can be desirable as well as undesirable, for example perceived unethical behavior or rule-breaking (Gino & Ariely, 2012; Khessina et al., 2018). Building on the classification used by Unsworth (2001) and Rangarajan (2008), creativity can be classified as either proactive or reactive. Reactive creativity concerns responsively coming up with ideas as solutions to occurring situations, whereas proactive creativity concerns prospectively coming up with ideas for open and undiscovered situations. Secondly, the element “work-related ideas” refers to a range of possible outcomes of these interactions, commonly named creative products (Puccio & Cabra, 2010). Thirdly, the element “employees” refers to the actors initiating creativity, in our case public servants working in public and semi-public organizations. Finally, the element of “novelty” indicates a degree of newness, with diverse magnitudes; from incremental additions and changes, named little-c creativity to radical new ideas, named Big-C creativity (Kozebelt et al., 2010; Mumford, 2012).

Literature on innovations by public sector organizations illustrates the wide range of possible public sector creative products. Examples are improved operation and management of service delivery (Joha & Janssen, 2010), adjusted management and administrative systems (Damanpour et al., 2018), new open-innovation platforms and procedures (Heimstädt & Reischauer, 2018; Loukis et al., 2017; Mergel & Desouza, 2013), practical and context-specific tailor-made solutions (Jessen & Tufte, 2014; Laitinen, 2015; Surva et al., 2016), revolutionary mobile notary public service, IoT, or blockchain applications and door-to-door public services (Lewis et al., 2020; Luu et al., 2018; Osorio et al., 2020) Thereby, creative products encompass both novel processes (e.g., procedures, work methods, systems) and novel outcomes (e.g., ideas, services, products). We base our search string on this diversity of public sector creative products.

2 METHOD

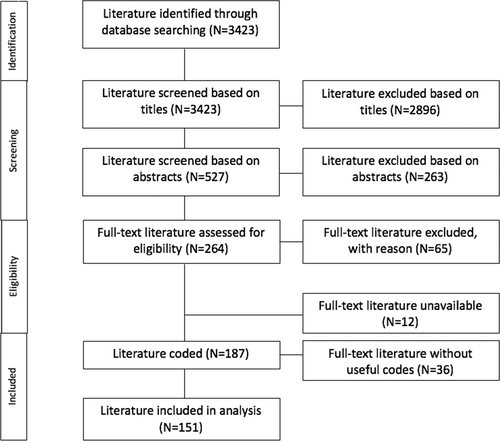

In order to safeguard validity and transparency, we apply a review procedure based on the PRISMA-P checklist and the PRISMA-P Flow Diagram (Moher et al., 2015) for identification, screening, assessment, and inclusion of literature for the sample.

The search string ensures unbiased selection of literature likely to discuss public sector creativity. Applying a search string consisting of possible synonyms for public sector creativity would base our search on assumptions, making it prone to biases. Therefore, we develop a search string that searches for literature mentioning a range of creative products, as this literature likely discusses, or at least mentions, practices applied by public servants to come up with their underlying ideas. We search for an extensive number of combinations of “novelty” adjectives (O'Quin & Besemer, 1999) and “product” objects that resemble public sector creative products (e.g., “original solutions,” “new practices,” “unorthodox methods,” or “unique ideas”). Based on the literature and a brainstorm, we compile an initial list, then use dictionaries and online synonym generators to add synonyms. A fellow researcher on public sector creativity reviewed the list and made additions and finally we reiterated the adding process. A list of 37 adjectives and 26 objects is compiled, resulting in a list containing 962 combinations that represent the range of public sector creative products (see Appendix A).

As the focus of our research is on creativity exerted by public servants in their endeavor to provide public services, we exclude creativity in the private sector and creativity within political stages of the policy cycle, predominantly the stages of decision-making and early (political) policy formulation. Therefore, we add the precondition that the literature also discusses public actors concerned with public services, for example, public servants, municipalities, and public executive agencies. This results in the following search string on an abstract level: TopicSubject = (“Public actors”) AND (“Adjectives” + “Objects”), for the full search string, see Appendix A. Using this search string, we search the Web of Science database for articles published between the January 2000 and March 2020.

- Implies that research is related to public services, and

- Encapsulates at least one term that can be interpreted as a possible creative product or a creative practice.

- The research concerns a creative practice regarding design, execution, implementation, or delivery of public services by public servants, and

- The research discusses or investigates phenomena that can be interpreted as either creative products or creative practices.

We analyzed our sample using Atlas.ti, coding practices for public sector creativity using the “emergent themes” method. Emergent themes analysis encompasses an inductive and iterative distillation process of voluminous amounts of qualitative data, in order to make sense of the data and reduce it to relevant text fragments that encapsulate specific phenomena, defined and categorized as specific themes, that provide information relevant to the research question (see also Thomas & Allen, 2006). In our case, themes encompass interpreted clusters of codes that resemble specific practices for public sector creativity that public servants apply in practice. The bulk of the analysis was done by the first author, with the second and third author both validating both themes and codes through independent coding of five randomly selected articles each. The resulting reliability report shows that with 70% overlap, the coding is largely consistent with explainable and justifiable differences. With all differences, the first author coded more strictly and demarcated in conformity with the method its criteria as described in this section. The emergent themes are interpreted, organized through clustering and hierarchy into templates, and discussed in the results section.

3 RESULTS: SAMPLE DESCRIPTIVE VARIABLES

Our sample contains 187 articles, originating from 40 countries across all continents, with a predominance of North-Western Europe (38%), followed by Northern America (17%), Southern Europe (12%), and Asia (11%). Our sample stems from 126 sources, predominantly journals on public administration and public policy (27%) and public management (12%), followed by journals on management (10%) and innovation (5%). Most articles in the sample are empirical (76%) as opposed to theoretical (24%). Within the empirical studies, there is a predominance of qualitative case study designs (42%), followed by quantitative survey designs (27%) and other designs under which mixed methods (12%). The majority of the sample discussed public servants and services in general (52%), followed by municipal public servants and services (14%) among others such as health and care service workers (9%) street-level bureaucrats (4%) and policing public servants (3%).

4 RESULTS: PRACTICES FOR PUBLIC SECTOR CREATIVITY

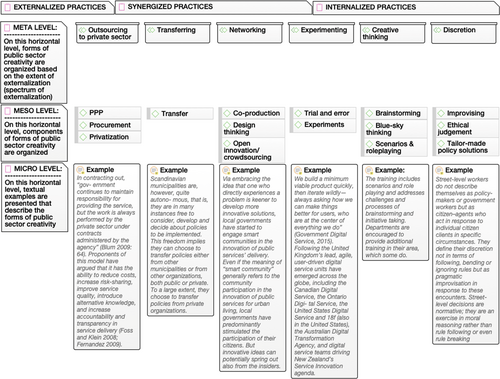

Based on our analysis of 187 articles that mentioned public sector creative products, we identify six practices for public sector creativity, shown below in Figure 2. This taxonomy of practices for public sector creativity indicates the different ways how public servants come up with ideas as mentioned within the literature on creative products. The practices are analytically distinct and are not mutually exclusive as public servants sometimes combine practices within an integral strategy. The practices for public sector creativity differ based on their fundamental mechanisms and the degree of creative input from public servants in the generation of the idea. The taxonomy is based on the difference in mechanisms and organized based on the degree of creative input from public servants, ordered from higher-input internalized practices to lower-input externalized practices. The identified practices for public sector creativity are (1) “creative thinking”; (2) “discretion”; (3) “experimenting”; (4) “networking”; (5) “transferring”; and (6) “outsourcing to private sector.”

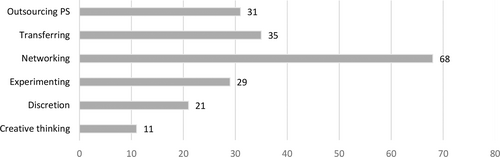

These six practices are discussed as applied in practice in 118 of the 187 articles, with the remaining 69 discussing these practices either in theory or discussing other practices indirectly related to creativity (e.g., conforming to top-down disseminated ideas). Some articles discussed multiple practices for public sector creativity. Figure 3 shows how many articles discuss these practices for public sector creativity applied in practice. For the full lists subdividing articles per applied practice for public sector creativity, see Appendix B. Figure 3 shows that “networking” is discussed notably more frequently, whereas “creative thinking” is discussed notably less frequently.

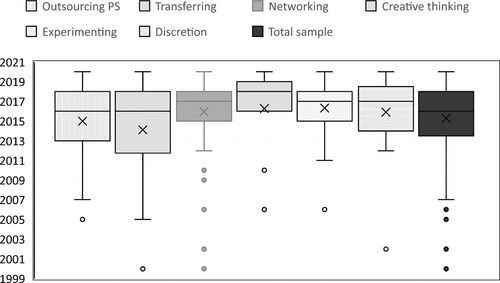

Figure 4 shows how the discussion of these practices for public sector creativity is spread across the selected time period. The boxplot shows that the discussion of “outsourcing to private sector” gained momentum in 2007 and was predominantly discussed between the years 2013 and 2018, with “networking” gaining momentum in 2012 with a later predominance between 2015 and 2018. “Creative thinking” gained momentum in 2016 and was predominantly discussed most recently, between the years 2016 and 2019.

4.1 Creative thinking

Mentioned in 11 articles of our sample, a first practice for public sector creativity encompasses autonomous and proactive creative thinking through which public servants generate public sector creative products. With autonomous and proactive creative thinking, public servants generate new knowledge through exploratory learning (Escribá-Carda et al., 2017). On an abstract level, autonomous and proactive thinking encompasses public servants “thinking outside the box” (Deschamps & Mattijs, 2018, p. 4910; Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017, p. 832), “deliberatively searching for opportunities to innovate” (Carnes et al., 2019, p. 439) or discussing “how things could be in the future and what is needed to get [the public sector] there” (Zampetakis & Moustakis, 2007, p. 23). Quintessential autonomous proactive thinking practices applied by public servants such as brainstorming (Berman & Kim, 2010; Lockert et al., 2020), blue-sky thinking (Wagner & Fain, 2017), scenarios, and roleplaying (Berman & Kim, 2010) share the common features that public servants autonomously and proactively seek to generate new knowledge in order to come up with public sector creative products. Although scarcely discussed in the literature, creative thinking is perceived as a key practice for generating creative products (Awang et al., 2020; Yasir & Majid, 2019). At the level of the public servant, autonomous proactive thinking is archetypically creative, as it represents public servants coming up with public sector creative products.

4.2 Discretion

Mentioned in 21 articles of our sample, a second practice for public sector creativity is public servants using their room for discretion to fit their performance to the unique situations they encounter. Public servants apply discretion when encountering specific situations that require “situational adjustment” (Jensen, 2015, p. 1128) or “pragmatic improvisation” (Buvik, 2016, p. 783), for example, when public servants have to deviate from rules, routines and procedures in order to address clients' needs or restrict clients' choices, or when they need to come up with solutions to deal with encountered uncertainties, shortcomings and complexities (see, e.g., Lu et al., 2019; Perna, 2019; De Corte et al., 2018;; Nugus et al., 2018; Franklin et al., 2016; Buvik, 2016; Tummers & Bekkers, 2014; Wihlman et al., 2014; Jessen & Tufte, 2014; Eilers, 2002). These context-specific decisions are made based on public servants' field-level expertise, knowledge, and day-to-day experiences that result from experiential learning (Buvik, 2016; De Corte et al., 2018; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, 2012), often combined with an ethical judgment based on a moral assessment of the situation (Buvik, 2016; Chew & Vinestock, 2012; Jensen, 2015; Jessen & Tufte, 2014; Perna, 2019). Public servants may even make an ethical judgment to challenge or break rules in order to innovate (Buvik, 2016; Ferguson & Blackman, 2017). These context-specific decisions lead to variations in practice (Jensen, 2015) described as tailor-made solutions (Jessen & Tufte, 2014; Laitinen, 2015; Surva et al., 2016), unorthodox methods (Surva et al., 2016), fixes for unanticipated events (Nugus et al., 2018), or unique solutions (Stenvall et al., 2014). Discretion differs from creative thinking in the sense that it specifically encompasses improvisation of reactive and context-specific decisions instead of proactive open thinking. At the level of the public servant, discretion can be regarded as highly creative as public servants improvise as part of context-specific approaches. Moreover, discretion is widely exercised by public servants in daily activities (Buvik, 2016; Lu et al., 2019) and the amount of discretion is perceived substantial (Busch & Henriksen, 2018; Buvik, 2016; De Corte et al., 2018; Nugus et al., 2018).

4.3 Experimenting

Mentioned in 29 articles of our sample, a third practice for public sector creativity encompasses public servants experimenting, generating public sector creative products through iterative processes based on trial, error, and adjustment. Experimenting is based on experiential learning with public servants continually applying the knowledge acquired during the process (Choi & Chandler, 2015; Damanpour et al., 2018; Fernandez & Moldogaziev, 2012; Fernandez & Pitts, 2011). Thus, experimenting encompasses an ongoing development process based on testing, feedback, and adjustment through which public servants generate creative products against an original concept. For example, public servants “build a minimum viable product quickly, then iterate wildly –always asking how [they] can make things better” (Clarke & Craft, 2018, p. 11). Public servants test options, trial implementation, pilot interventions, and prototype tools (see e.g., Clarke & Craft, 2018; Damanpour et al., 2018; Hyvärinen et al., 2015; Landry et al., 2011). Experimenting differs from creative thinking and discretion because of its specific iterative trial-and-error nature. At the level of the public servant, experimenting can be regarded creative as public servants come up with novel products, namely smaller-c adjustments and improvements, that subsequently can also be part of an ongoing experimental process developing and/or implementing Capital-C public sector creative products.

4.4 Networking

Mentioned in 68 articles of our sample, a fourth practice for public sector creativity encompasses public servants networking with stakeholders in order to collaboratively generate public sector creative products. Networking arrangements share the baseline that public sector creative products are generated through collaborative arrangements that spur (mutual) learning based on shared knowledge and creative input of stakeholders, and with some arrangements public servants (Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017; Osorio et al., 2020; Sørensen & Torfing, 2016). These networking arrangements shape interactive and open governance spaces (Storbjörk et al., 2019) by providing a degree of autonomy for stakeholders, and with some arrangements public servants, to collaborate and compete in order to generate public sector creative products (Österberg & Qvist, 2018). A diversity of networking arrangements is identified, namely co-production including co-initiation, co-planning, co-creation co-design, and co-delivery as well as other arrangements such as collaborative planning, open-innovation, and design thinking (see e.g., Lewis et al., 2020; Mergel & Desouza, 2013; Österberg & Qvist, 2018; Sørensen & Torfing, 2016; Storbjörk et al., 2019; Zurbriggen & Lago, 2019). Various work forms are applied to give body to the arrangements, for example, collective workshops on knowledge-transfer, trainings, study-visits, focus-groups, and hackathons (Heimstädt & Reischauer, 2018; Lewis et al., 2020; Osorio et al., 2020; Storbjörk et al., 2019). Moreover, Public Innovation Labs/Hubs are prime facilities housing networking arrangements, encompassing physical and/or digital facilitative environments that bring stakeholders together with the goal of collaboratively generating public sector creative products (Lewis et al., 2020; Osorio et al., 2020; Zurbriggen & Lago, 2019). At the level of the public servant, networking can be considered creative if public servants actively participate in the collaborative process, although they often only act as the orchestrators (Janssen & Estevez, 2013), mediators (Storbjörk et al., 2019), promotors (Österberg & Qvist, 2018) agenda-setters, or facilitators (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000).

4.5 Transferring

Mentioned in 35 articles of our sample, a fifth practice for public sector creativity encompasses public servants transferring creative products generated elsewhere and adopting them in the public sector. With transferring, public servants learn from knowledge generated in other time periods, countries, (similar) public organizations and to a large extent the private sector and apply this knowledge to their situation (see e.g., Lockert et al., 2020; Zhang & Yu, 2019; Aalto & Kallio, 2019; Ferguson & Blackman, 2017; Heimstädt & Reischauer, 2018). Ideas and solutions generated elsewhere are transferred by public servants and applied to their own domain (Kruyen & Van Genugten, 2017) through mimicking, adapting, combining—or being inspired by—one or more selected elements of designs, instruments, tools, ideas, goals, values, strategies and tactics regarding policies, services, administrative arrangements, and institutions (see e.g., Lockert et al., 2020; Ferguson & Blackman, 2019; Askim et al., 2018; Fernandez & Pitts, 2011; Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000). At the level of the public servant, transferring can be regarded to range from creative when transferred knowledge inspires public servants to develop a public sector variation to rather uncreative when creative products are simply copy-pasted.

4.6 Outsourcing to private sector

Mentioned in 31 articles of our sample, a final practice for public sector creativity encompasses public servants outsourcing creativity toward the private sector, to let the private sector develop or produce public sector products in a more creative and innovative way (Michelucci & De Marco, 2017; Ohemeng & Grant, 2014; Sharma et al., 2020). This engagement of the private sector ranges from leveraging resources for services to completely reconfiguring the services (Hora & Schreiber, 2018; Liddle & McElwee, 2019). Outsourcing can take place in three analytically distinguishable forms: collaborative outsourcing through multiple cooperative forms of public–private partnerships, controlled outsourcing through predeveloped request via procurement, and complete outsourcing through privatization (see, e.g., Furlong & Bakker, 2010; Ohemeng & Grant, 2014). At the level of the public servant, outsourcing can be regarded as moderately creative to uncreative, depending on the degree of outsourcing and public servants' creative input in the process.

5 DISCUSSION

The identification of six practices for public sector creativity for our taxonomy illustrates a first feature of public sector creativity, namely that it is diverse and encompasses multiple practices for creativity that vary based on the mechanisms applied by public servants (e.g., “networking,” “transferring,” or “creative thinking”). These practices are analytically distinct but can be combined such as with networking and experimenting, when solutions are iteratively refined and adjusted based on feedback from stakeholders (Clarke & Craft, 2018; Munthe-Kaas, 2014; Sørensen & Torfing, 2016; Wagner & Fain, 2017) which often takes place in Innovation Labs/Hubs (Fernandez & Pitts, 2011; Zurbriggen & Lago, 2019). What stands out is that the literature predominantly covers creative practices by public organizations as unit of analysis as opposed to individual public servants, resulting in an underrepresentation—or perhaps nonrepresentation—of creative practices on a micro-level within the current literature.

Our taxonomy illustrates a second feature, namely that public servants are not always creative in the sense that they generate ideas autonomously, but are additionally creative in finding alternative ways to come up with ideas for the public sector. Therefore, we define public sector creativity as “public servants coming up with novel and useful ideas through various practices.” With these practices, public servants are involved to different extent in generating the initial idea. With certain practices for creativity, public servants are autonomously creative, such as with the frequently covered “discretion” and “experimenting,” or with the less frequently covered “creative thinking.” However, the generation of the initial idea is also frequently—at least in part—externalized, such as with “transferring,” “outsourcing to the private sector” and “networking.” This illustrates that public servants are creative in finding various ways to come up with ideas for the public sector, be it autonomously or externally generated. Thus, public servants apply multiple, distinctive practices for public sector creativity in order to come up with novel and useful ideas for public sector innovations.

On a deeper level of analysis, a third feature of public sector creativity is that these practices differ in their degree of involvement of public servants in the generation of the initial idea, which we call the spectrum of externalization. The spectrum of externalization ranges from autonomous (full involvement public servants, e.g., “creative thinking”), synergized (semi-involvement public servants, e.g., “networking”) to externalized (no involvement public servants, e.g. privatization as part of “outsourcing to private sector”). The application of this diversity of practices by public servants indicates that public sector creativity is broader than existing definitions imply. The reasons for externalization can be understood in light of arguments made by Bommert (2010) that opening up idea generation phases for input from external actors results in positive effects such as overcoming restrictions for creativity, increasing legitimacy of solutions, spur risk-taking, and thereby increase the quantity and quality of creative outcomes.

Another notable feature is that the practices for public sector creativity vary in their types of learning and knowledge applied by public servants, illustrating the central role of knowledge and learning in public sector creativity, as well as the diversity of learning styles and types of knowledge that can be applied to generate to public sector creative products. To illustrate, “experimenting” is based on experiential learning through applying knowledge generated during the process, whereas “networking” is based on mutual learning synergizing shared knowledge, while “creative thinking” is based on exploratory learning encompassing discovering new knowledge.

A final feature of public sector creativity is that almost all practices for public sector creativity lean toward reactive creativity, instead of proactive creativity. Apart from “creative thinking” (and “experimenting” as a possible hybrid form as the act itself is prospective, but the processing of feedback is reactive), all identified practices for public sector creativity are rather reactive from the perspective of public servants. Moreover, “creative thinking” is notably less covered within the examined literature than reactive forms, which illustrates a lack of research into this micro-level practice. This coverage by the literature leads to the impression that public sector creativity predominantly concerns reactively improving existing and occurring situations, instead of proactively anticipating on upcoming opportunities, contrasting findings by Rangarajan (2018) who found a predominance of proactive creativity, albeit based on research of award-winning public sector ideas.

Temporal analysis of the practices for public sector creativity reveals a trend, namely that the rationale of the most frequently covered practices for public sector creativity—with a slight delay and considerable residue—run parallel to the rationale of their corresponding paradigms. For each time period, the practices and degrees of public servants' involvement in the newest and most frequently covered practices for public sector creativity fit their corresponding, most recent paradigms. To illustrate, the NPM-paradigm emphasized the introduction of market mechanisms (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000; Österberg & Qvist, 2018; Sørensen & Torfing, 2016) consistent with the subsequent emergence and predominance of “transferring” and “outsourcing to the private sector” in the literature, then the NPG emphasizes networks and stakeholder involvement (Liddle & McElwee, 2019; Österberg & Qvist, 2018; Scupola & Zanfei, 2016) consistent with the subsequent emergence and predominance of “networking” in the literature (as substantiated by Figure 4) and most recently the rise of autonomous proactive “creative thinking” in the literature might hint at the rise of a new paradigm regarding public sector creativity and innovation. This trend illustrates that rationales of the emerging and predominant practices for creativity fit the rationale of the paradigm of that period. Moreover, the subsequence in rationales of the practices for creativity appear to be logical reactions to the shortcomings of their predecessors, parallel to the subsequent paradigms being logical reactions to the shortcomings of their predecessors (Houtgraaf, 2018).

6 RESEARCH AGENDA

Our research indicates hiatuses in research on public sector creativity, raising new questions regarding public sector creativity. We provide a future research agenda mapping notable remaining substantive hiatuses as avenues for future research and advise on viable methods to address them.

6.1 Substantive

In terms of substantive hiatuses, both the existing body of research on public sector creativity and this research are limited regarding the insight generated in the specific internal dynamics of the identified practices for public sector creativity. The practices for public sector creativity covered within the literature offer limited insight into the possible diversity and complexity of internal dynamics, as the literature only covers the generic rationale of the practices or specific dynamics in case studies. Future research should focus on clarifying these internal dynamics, for example the idiosyncratic stages of their creative processes and factors that stimulate and inhibit these processes. Apart from filling the hiatus on idiosyncratic stages and factors of public sector creative processes, these findings will also prove relevant for practitioners in order to improve public sector creativity. Moreover, these findings can be used in comparative research in order to illustrate and explain the differences public sector creativity and its private sector counterpart. Furthermore, future research can investigate how these factors can be altered in order to improve creativity of practitioners, for example, through targeted training improving stimulating factors and counteracting inhibiting factors.

Secondly, we call for more research into the magnitude of creative products that public servants come up with. Both the existing body of literature and our systematic review fall short in generating knowledge on the actual ratio of little-c versus Big-C ideas generated by public servants, nor if Big-C public sector creative products are predominantly generated autonomously or externally. Future research into these matters is needed to shed light on the state of affairs within the public sector in terms of creativity and offer knowledge on how (frequently) Big-C ideas are generated for the public sector.

Third, we call for more research into the ratio between proactive versus reactive creativity and autonomous versus externalized creativity in the public sector. Our review indicates a predominance of reactive and externalized creativity in the literature, implying a predominance of reactive and externalized creativity in practice. However, coverage in the literature might not be representative for actual degrees of application. Furthermore, these findings are in contrast with Rangarajan's (2018) findings. Future research will have to clarify this feature of public sector creativity in order to assess its nature and corresponding implications.

Fourth, as our review indicates that little to no research delves into the “dark side of creativity,” we call for more research into this aspect of creativity. Although Khessina et al. (2018) and Gino and Ariely (2012) warn for potential downsides of creativity, in our sample only Kruyen and Van Genugten (2017) implicitly link public sector creativity to negative consequences. More research is needed to explore the potential downsides as a connotation to the aspiration for creativity.

Sixth, based on our findings regarding the substantial correspondence and temporal parallelism of practices for public sector creativity and paradigms in the literature, we call for future research to investigate whether these findings and trends correspond with the experiences of practitioners and if any paradigmatical shift regarding creativity is currently taking place.

6.2 Methodological

In terms of methodological avenues, we call for more qualitative explorative research into public sector creativity. This systematic literature review indicates that there is a paucity of research on the public sector creativity. Qualitative explorative research enables expanding the knowledge base on public sector creativity, which is currently too thin a starting point. Furthermore, explorative research offers the opportunity of an unbiased approach to point out idiosyncrasies of public sector creativity as leads for focused research. After mapping these idiosyncrasies, focused quantitative methods can be applied to measure and test findings in order to deepen understanding and increase rigidity.

Secondly, we call for longitudinal field research into public sector creativity as a viable research design to address the hiatuses indicated by our theoretical research. Longitudinal field research will present a more complete and representative image of the features of public sector creativity, based on more reliable and representative empirical observations of creativity applied by public servants in daily practice. For example, longitudinal field research can adequately map aspects of public sector creativity in practice, such as dynamics of creative processes, the ratio between magnitudes of ideas, and the ratio between proactive and reactive creativity. Two significant strongpoints of longitudinal designs in terms of researching creativity are that it enables to track processes of creativity and subsequent innovation, as well as avoiding the chance of over−/underrepresenting rare ideas.

Third, we call for research with individual public servants as unit of analysis as our review of the literature indicates that this perspective is fairly absent leading to bias in coverage on practices. Our findings indicate that micro-level practices are underrepresented or even unrepresented within the literature. However, this likely to be biased as our review of the current literature mainly focuses on the organizational level as a unit of analysis instead of the individual level. Future research focusing on individual public servants as units of analysis allows for complete and unbiased knowledge on the creative practices public servants apply.

Fourth, we call for experimental research to measure the possibility of improving public sector creativity through interventions, entailing significant implications and tools for practitioners. We advise that these interventions should focus on improving or countering the idiosyncratic aspects on which public sector creativity appears to fall short according to research into the topic and measure the effects of these interventions. This type of research will provide knowledge for practitioners on which factors and methods are viable approaches to improve public servants' creativity and thereby the innovativeness of their organizations.

Finally, we call for future research to extend the limited scope and depth of our research. First, by looking into earlier time periods as our research includes literature published between the year 2000 and 2020 and thus emphasizes contemporary practices for public sector creativity. Future research into earlier time periods will shed light on public servants came up with ideas were in earlier time periods, for example, when the traditional Public Administration paradigm was dominant. Secondly, future research can extend our search string in order to add more rigor to our findings. Thirdly, future research can deepen our analysis by investigating which practices are covered most frequently in specific types of public organizations or sub-sectors.

7 CONCLUSION

Based on our findings, we conclude that public servants come up with novel and useful ideas for public sector innovations through multiple, distinctive practices for public sector creativity. Existing definitions of creativity proved to be too narrow and unspecific to be directly applied to the public sector. Therefore, we define public sector creativity as “public servants coming up with novel and useful ideas through various practices.” This research merged the scattered literature on public sector creativity into a comprehensive taxonomy of six practices for public sector creativity covering how public servants come up with ideas for public sector innovations. These practices for public sector creativity vary in their mechanisms and the extent of actual creative input from public servants during the generation of the initial idea. Thus, our findings indicate that public servants are not always creative in the sense that they autonomously generate ideas, as they also leave this to other actors, but it appears that they are often creative in finding alternative practices to come up with ideas for the public sector.

However, our systematic review of the literature also indicates hiatuses in knowledge regarding public sector creativity for which we provide a future research agenda with important avenues for future research. We call for future research to delve into idiosyncratic characteristics of public sector creativity, the dynamics of its processes, and the types of outcomes. Furthermore, we offer methodological suggestions on how to adequately address these hiatuses.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was funded by the official Dutch Organization for Scientific Research through the Open Competition contest under grant #27000931.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request