Levelling the playing field in police recruitment: Evidence from a field experiment on test performance

Abstract

How to increase diversity in the police is an unanswered question that has received significant political and media attention. One area of intervention is the recruitment process itself. This study reports the results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in a police force that was experiencing a disproportionate drop in minority applicants during one particular test. Drawing on insights from the literatures on stereotype threat, belonging uncertainty and values affirmation exercises, we redesigned the wording on the email inviting applicants to participate in the test. The results show a 50 per cent increase in the probability of passing the test for minority applicants in the treatment group, with no effect on white applicants. Therefore, the intervention closed the racial gap in the pass rate without lowering the recruitment standard or changing the assessment questions.

1 INTRODUCTION

In the United States, three out of every four police officers are white, making police forces almost 30 percentage points more white than the communities they serve (Ashkenas and Park 2014). After incidents in Ferguson and other cities, both the popular press and policy-makers have highlighted the urgency of improving the diversity of police forces across the country (United States Department of Justice 2015). Similarly in the United Kingdom, all major political parties listed improving the diversity of the police as part of their 2015 election campaign platforms. At its core, this goal is grounded in theories of representative bureaucracy; the argument that a more diverse civil service will allow government to more accurately reflect the preferences of—or better serve the needs of—a diverse public (see Kennedy 2014 for an overview). Specifically, a more representative bureaucracy may impact citizens' perception of public sector legitimacy (Theobald and Haider-Markel 2009) but may also directly influence the ability of the public sector to serve the public effectively (Weitzer and Tuch 2006; Bradbury and Kellough 2011). In policing, recent evidence suggests that these theories hold true. Not only are more diverse police forces perceived as more trustworthy and fair (Riccucci et al. 2014), they also correlate with positive outcomes ranging from less crime (Hong 2016) to better reporting of sexual assault (Meier and Nicholson-Crotty 2006). While we may need more causal evidence linking changes in diversity to better policing outcomes, the public management question remains: how can public sector organizations recruit a more diverse civil service?

The literature has often focused on assessor bias to explain racial disparity in recruitment. Multiple audit studies have shown, for example, that people with names that sound traditionally black (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004) or more foreign (Oreopoulos 2011) receive fewer call-backs even if they have identical CVs. Other studies show biases in interviews and other stages in the assessment process (see Linos and Reinhard 2015 for a summary). However, more and more components of recruitment are now automated or scored without using human assessors. Yet large racial or gender gaps in performance persist. This is either due to the test being biased (see Jencks and Phillips 1998 for an overview) or to the testing context. Importantly, potential solutions to reducing assessor bias have shown mixed results. Large field experiments—all conducted outside a police recruitment context—have shown that blinding CVs may not lead to recruiting more individuals from underrepresented groups (Behaghel et al. 2011); and implicit bias training does not seem to improve behaviour and may even backfire (Duguid and Thomas-Hunt 2015). Public managers may therefore have to turn to the candidate experience to try to improve recruitment outcomes for people of colour or other underrepresented groups.

A large parallel literature has documented racial performance gaps in educational settings and test-taking. The seminal work on stereotype threat (Steele and Aronson 1995) has been shown to affect student performance on tests, and has been replicated in the lab and in the field multiple times. For example, telling a woman before she takes a test that female test-takers do worse has been shown to significantly decrease their performance (Spencer et al. 1999). The mechanism underlying these effects is probably linked to increased anxiety (Osbourne 2001), emotional regulation (Johns et al. 2008), and mental workload (see Schmader et al. 2008): individuals worry about confirming a stereotype about themselves or their group, which in turn leads to underperformance (see Blascovich et al. 2001).

We expect that stereotype threat applies beyond educational settings, but there may be additional mechanisms at play in recruitment-specific environments. For example, in a recruitment process, both the applicant and the assessor may be using the assessment tasks as a way to ascertain ‘person–organization’ (P–O) fit, especially if these tasks are presented as realistic work scenarios. Drawing on Cable and Edwards' (2004) framework for understanding P–O fit, candidates may be using the selection process to assess values congruence or supplementary fit. But they may also be trying to ascertain complementary fit: whether the organization will satisfy an individual's psychological needs. While psychological needs can be broadly defined, according to self-determination theory they include autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci and Ryan 2014). Here, the notion of belonging uncertainty (Walton and Cohen 2007) may be most relevant. If individuals are uncertain of their social bonds—or levels of relatedness–and are trying to gauge how they will fit within an organization, cues that suggest social isolation may adversely impact performance. At this stage in the recruitment process, the assessment tasks themselves may provide cues of belonging or non-belonging that are especially salient for those individuals who are uncertain of their likely social bonds in a given organization. More specifically, we expect that individuals who are underrepresented—in this case black and minority ethnic applicants—would be more likely to be uncertain of their social bonds on the job.

While the phenomenon is clear, whether and how it might be reversed is less so (Ambady et al. 2004). By definition, stereotype threat operates in environments where a stereotype is presumed to be relevant. Thus, it is plausible that priming someone to view the presumed stereotype as irrelevant may improve performance. We know, for example, from early work in this field that African American students performed better on an IQ test if it was presented as a hand–eye coordination test, and therefore any negative stereotype on IQ was not relevant (Katz et al. 1964). More recent work suggests that when intelligence is presented as malleable, rather than fixed, African American GPAs increase, compared to a control group (Good et al. 2003). Moreover, if the underlying mechanism is increased anxiety or mental workload, as has been shown in other cases (Osborne 2001), then language that reduces anxiety should diminish the racial gap in achievement.

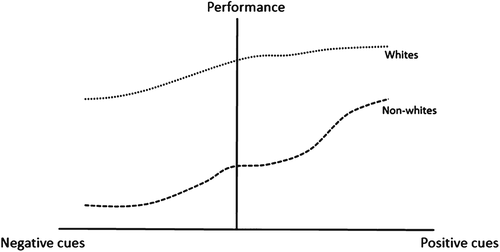

Walton and Cohen (2007) describe belonging uncertainty as a hypothesis—rather than a belief—that one may not belong socially, and therefore something that is malleable. For example, in one study, reframing adversity on campus as common and not as an indictment of whether a person of colour ‘belongs’ seems to significantly impact GPA for African American students (Walton and Cohen 2011). Thus, belonging uncertainty should respond (in the Bayesian updating sense) to counter-evidence that implies social belonging. We hypothesized that since applicants from underrepresented groups should be more likely to feel uncertain about their levels of belonging, they should also be more responsive to cues of belonging than would be their white counterparts. The slope—as it were—of a cue-performance line is steeper for non-whites, although the line itself may lie below that of whites. This hypothesis is shown graphically in figure 1.

In addition, a growing body of literature suggests that values affirmation exercises also positively affect performance. Self-affirmation theories suggest that when an individual's sense of self-integrity is threatened—their ‘moral and adaptive adequacy’ (Steele 1988)—they seek ways to restore their self-worth. Priming individuals to think about what they value may reduce anxiety and help reduce perceived threats; specifically, by reflecting on self-defined core values, individuals can re-establish personal worth, ultimately protecting themselves from psychological threat that impacts performance (Miyake et al. 2010; Harackiewicz et al. 2014). Importantly, although the initial theory focused on individual threats and individual responses, the same mechanism can apply to social group identities and social group threats (Sherman and Cohen 2006). Values affirmation exercises operate by reducing the threat of a negative characterization of a valued social identity. As a result, asking candidates to reflect on their values while providing a clear pathway for their social identity to be specifically valued in a police setting may increase their sense of self-worth in a similar fashion. Indeed, because values affirmation exercises operate by buffering against anxiety and mental workload (Creswell et al. 2005), they should improve performance for those candidates who face additional anxiety due to stereotype threat.

With this literature and hypotheses in mind, it seemed plausible to design an intervention intended to reduce the racial performance gap on assessment tasks for police recruitment. Just as in educational settings, we hypothesized that—holding ability and skills constant—non-white applicants would perform worse on tests. We also hypothesized that non-white candidates may be uncertain about their social value within the police force and as representatives of the police among civilians. Thus, we hypothesized that changing the language that applicants saw before taking the test to (a) make it more welcoming, (b) remove anxiety-inducing sentences and (c) ask candidates to reflect on their social value in the police would improve performance of non-whites and not affect white applicants. The design and results of the field experiment are presented below.

2 METHOD

2.1 Setting

This RCT was implemented by a UK police force with an open recruitment round. While 6.8 per cent of the region's population identified as either black or of an ethnic minority, only 2.5 per cent of the police force was non-white. During this period, there were multiple references to police diversity in the national press, with one of the largest minority police officer groups, the Black Police Association (BPA), noting, ‘The association still believe that the police service is institutionally racist’ (Muir 2013). The specific police force involved in this trial had also recently handled negative press and media attention, due to the tragic death of an individual that some (including the families of the victim) linked to institutional racism (Morris 2015). As such, there is reason to believe that in this setting—a high-stakes testing environment, when questions of race and the police are very salient—candidates from underrepresented groups may face stereotype threat.

In previous recruitment rounds, the force had seen a disproportionate drop in non-white successes in one key stage of the assessment process, an online Situational Judgment Test (SJT). The SJT is an online test that is meant to capture how potential recruits would react to different realistic situations in which they may find themselves as a police officer; some in interactions with other police officers and some in interactions with members of the public. These scenario-based questions ask candidates to rate four potential responses or actions on a scale from 1 (Counterproductive) to 4 (Effective). The test is meant to measure four core competencies: Communication and Empathy, Customer Focused Decision Making, Openness to Change and Adaptability, and Relationship Building and Community. Applicants see approximately five questions for each category.

Also in previous recruitment rounds, although approximately 5 per cent of initial applicants to the police force were classified as non-white, only 3 per cent of those who passed the test were non-white. Because baseline data such as demographics were limited, we were not able to explore whether the disproportionate drop in performance could be attributable to other factors related to educational attainment or previous experience. However, the test questions are meant to explicitly capture judgement rather than knowledge. Moreover, given that the test was administered online and scored automatically, we know that the lower scores of non-white applicants were not due to scorer bias. Rather, barring any difference in the quality of applicants, it is either the case that what is considered a correct response is racially biased, or that the expectations of test-takers affected their ability to perform well on the test.

2.2 Experimental manipulation

The intervention involved changing the email that half of the eligible applicants received before taking the SJT. All applicants that reached this stage in the assessment process were included in the study. The email was sent by the human resources (HR) department of the force and included the link to the test itself; this was the only communication eligible applicants received at this stage in the process. The email that the HR department had created and used in previous rounds of testing was used as the control. The main changes made to the letter are shown below.

First, we removed any language that was unnecessary and may have caused anxiety. Specifically, this meant removing a sentence that read: ‘Please note there is no appeals process for this stage.’ Similarly, to reduce anxiety, we changed instructions to the link to begin, ‘When you are ready ...’ and moved any technical specifications to the end of the email.

Second, we changed the language to be more positive and to prime success and belonging. In practice, this meant beginning the email with ‘Congratulations!’ and ending it with ‘Good luck!’ It also meant adding language that read: ‘You successfully completed the Behaviour Style Questionnaire and have been selected to participate in the next stage of the assessment process: the Situational Judgement Test.’

Finally, we added the following sentence: ‘Before you start the test, I'd like you to take some time to think about why you want to be a police constable. For example, what is it about being a police constable that means the most to you and your community?’ The purpose of this sentence was to prime candidates to reflect on their values and to also prime them to consider their presence in the police force as a valued social identity vis-a-vis underrepresented communities.

We deliberately combined the best insights from the relevant literature for the purposes of this intervention because there was no way to know ex-ante how successful each component would be in a recruitment context. Therefore, given a limited sample size and a field experiment where maximizing social impact and providing a quality improvement was crucial, a bundled intervention was most appropriate. We note that although we draw on multiple strands of research, each of these approaches points to a similar underlying psychological and physiological mechanism: a reduction in mental workload associated with stereotyping or perceived non-belonging. Thus, although each change serves as a distinct lever, this new treatment email can also be conceptualized as a multifaceted intervention aimed at reducing anxiety for underrepresented groups in order to improve performance. Given that this approach produced large effects in a recruitment setting, follow-up studies with a larger sample could tease out the specific impact of each of these changes separately.

2.3 Experimental design

This trial was a randomized controlled trial, with randomization at the individual level and stratification by racial category (white/non-white).

Table 1 presents summary statistics for the population of applicants that made it to this stage in the application process. The applicant pool at this stage is 90 per cent white and about 65 per cent male. While we do not have exact age data, 48 per cent of the sample is less than 25 years old. Almost all applicants (97 per cent) list English as their first language. The average pass rate is 60 per cent, although as we will show, this depends heavily on the race and treatment allocation of applicants. About 95 per cent of eligible applicants took the test, and each took on average 40 minutes to complete it. While there is a long right tail on time taken to complete the test, dropping applicants who look like outliers because of the time it took them to complete the SJT does not significantly change any of the results.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | Mean | Min | max | SD |

| White | 1,673 | 0.908 | 0 | 1 | 0.289 |

| Male | 1,669 | 0.653 | 0 | 1 | 0.476 |

| Age category | 1,662 | 1.558 | 1 | 4 | 0.569 |

| English as first language | 1,682 | 0.968 | 0 | 1 | 0.175 |

| Heterosexual | 1,560 | 0.906 | 0 | 1 | 0.291 |

| Pass | 1,601 | 0.577 | 0 | 1 | 0.494 |

| Took test | 1,682 | 0.952 | 0 | 1 | 0.214 |

| Minutes taken to complete test | 1,601 | 40.40 | 0 | 512.1 | 27.16 |

- Note: This table summarizes means and ranges of the key observable characteristics of applicants as well as their test-taking behaviour.

Table 2 summarizes the means on gender, age category, race, language, and sexual orientation by treatment group (columns 1 and 2) and t-tests on a difference in means (column 3), as well as a logit model on these covariates, where the outcome variable is assignment to the treatment group (column 4). Put simply, table 2 verifies that the randomization was effective and that the two groups look similar on pre-treatment characteristics and demographics. As the table confirms, there are no statistical differences between treatment and control on gender, age, race, language, and sexual orientation.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean (SD) Treatment group | Mean (SD) Control group | t-test difference | Logit model: Treatment |

| Male | 0.658 | 0.648 | −0.444 | 0.0134 |

| (0.0272) | ||||

| Age category | 1.55 | 1.57 | 0.631 | −0.0158 |

| (0.0229) | ||||

| White | 0.906 | 0.910 | 0.299 | 0.0383 |

| (0.0577) | ||||

| English as first language | 0.966 | 0.971 | 0.697 | −0.111 |

| (0.0876) | ||||

| Heterosexual | 0.902 | 0.911 | 0.602 | −0.0259 |

| (0.0467) | ||||

| Observations | 1,539 |

- Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01,

- ** p < .05,

- * p < .1.

- Note: This table shows means by treatment group, a t-test on whether the means are different, and the marginal effects of a logit model on treatment, testing whether any observable demographics seem to be associated with treatment allocation. If the randomization worked, these coefficients should all be non-significant.

The main outcome of interest was performance on the test, measured in two ways: percentile score, and probability of passing the test. Given the hypotheses, the main coefficient of interest was the interaction between treatment and race, showing the differential effect of the treatment email on non-whites. In order to explore mechanisms, we also measured the impact of the treatment on taking the test (a small percentage of applicants drop out before taking the test), and the time it took to complete the test.

3 RESULTS

Table 3 displays the main results of the trial. Column 1 presents a simple regression model on the percentile score for applicants by treatment group. There is no statistically significant effect on the population as a whole. Column 2 presents the treatment interacted with race. Here effects are highly significant. Non-white applicants in the treatment group gained 12 percentage points in their percentile ranking. White applicants show a two percentage point increase in their percentile ranking. Controlling for age category and gender in column 3 does not change the results significantly. However, it is interesting, given the make-up of the police, that women seem to do significantly better (4.5 percentage points better) on this online test.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Overall percentile | Overall percentile | Overall percentile |

| Treat | 1.532 | 11.75** | 12.15** |

| (1.434) | (4.935) | (5.171) | |

| Treat * White | −11.22** | −11.57** | |

| (5.156) | (5.380) | ||

| White | 13.48*** | 16.34*** | |

| (3.691) | (3.791) | ||

| Age category | 0.529 | ||

| (1.257) | |||

| Male | −4.510*** | ||

| (1.522) | |||

| Constant | 49.59*** | 37.38*** | 36.64*** |

| (1.023) | (3.535) | (4.468) | |

| Observations | 1,601 | 1,593 | 1,572 |

| R-squared | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.019 |

- Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01,

- ** p < .05,

- * p < .1.

- Note: This table presents the effect of the treatment, and the effect of the treatment interacted with race, on the percentile ranking of applicants.

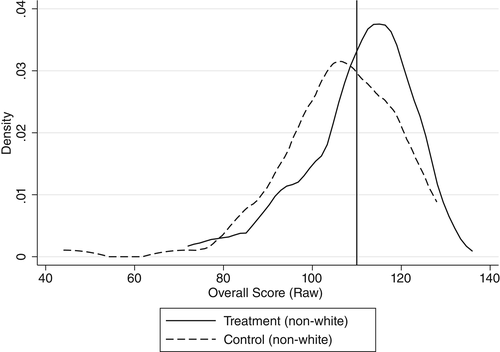

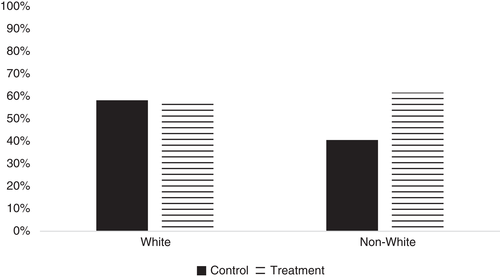

Figure 3 and table 4 present the results in terms of the probability of passing the test. Each column presents the marginal effects of a logistic regression model, where the outcome variable is 1 if the applicant passed to the next stage in the process and 0 otherwise. The results match table 3, but also show the practical impact of the treatment. Non-white applicants in the treatment group are 21 percentage points more likely to pass the test. Given that the control group pass rate for non-whites is 40.6 per cent, this is essentially a 50 per cent increase in the probability of passing the test. Most importantly, while the intervention closed the racial gap in percentile score by about 80 per cent, it fully closes the racial gap in the probability of passing the test because of the way scores are distributed. More precisely, as figure 2 suggests, the peak of the score distribution for non-white applicants in the control group is right below the cut-off for passing (which is set at 110), so improving scores has a disproportionately larger effect on pass rates. As is also shown, white applicants in the treatment group are three percentage points less likely to pass, but this effect disappears once we control for age and gender.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Probability of passing | Probability of passing | Probability of passing |

| Treat | 0.0213 | 0.206** | 0.220** |

| (0.0247) | (0.0804) | (0.0855) | |

| Treat * White | −0.204** | −0.219** | |

| (0.0851) | (0.0900) | ||

| White | 0.177*** | 0.215*** | |

| (0.0623) | (0.0649) | ||

| Age category | 0.0103 | ||

| (0.0221) | |||

| Male | −0.0459* | ||

| (0.0263) | |||

| Observations | 1,601 | 1,593 | 1,572 |

- Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01,

- ** p < .05,

- * p < .1.

- Note: This table presents the marginal effects of a logit model on the probability of passing the SJT test.

Note: This graph displays the distribution of raw scores on the test for non-whites in the treatment and control groups, respectively. The cut-off passing score is 110.

While this trial, by design, does not determine the relative contributions of each change in the email, we can use additional analyses to rule out some mechanisms and provide suggestive evidence of others. Table 5 does just that. Given that the email itself was sent before people took the test, and that all recruitment processes have some attrition at each stage, it is possible that the impact of the intervention lies in getting different people to take the test. This does not seem to be the case. Column 1 shows whether being in the treatment group predicts the probability of taking the test. For a non-white applicant, being in the treatment group does not predict whether an applicant will take the test. It is also possible that the intervention motivates applicants to concentrate more during the test or take the test more seriously. While it is hard to observe concentration and overall effort, we can measure the time applicants took to answer questions on the test as a proxy. Column 2 presents a regression on the impact of treatment on the time taken to complete the test. This, too, does not seem to cause the effect; being a non-white applicant in the treatment group does not predict how much time the applicant spends on the test. Indeed, in the control condition, white applicants seem to be spending significantly less time on the test than their non-white counterparts.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Took test | Time taken (minutes) |

| Treat | 0.000675 | 0.458 |

| (0.0270) | (5.945) | |

| Treat * White | −0.00923 | −0.694 |

| (0.0298) | (6.103) | |

| White | 0.0518 | −12.19*** |

| (0.0385) | (3.795) | |

| Age category | 0.00272 | 1.790 |

| (0.00912) | (1.159) | |

| Male | 0.0138 | 1.372 |

| (0.0114) | (1.356) | |

| Constant | 48.00*** | |

| (4.089) | ||

| Observations | 1,652 | 1,572 |

| R-squared | 0.019 |

- Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01,

- ** p < .05,

- * p < .1.

- Note: This table shows the marginal effect of a logit model on the probability that someone took the test and a regression on the number of minutes taken to complete the test.

The SJT itself splits questions into four categories based on the competencies meant to be tested. These are: Communication and Empathy, Customer Focused Decision Making, Openness to Change and Adaptability, and Relationship Building and Community. Table 6 identifies the results by category. Of these four areas, Communication and Empathy seems to drive the effects of the intervention, which given its nature, may seem appropriate. We primed individuals to feel more comfortable and to recall their values and their own role in their community. If this is true, we should not expect the intervention to affect an applicant's level of adaptability, for example, and indeed we do not see an effect in this category. As table 6 shows, with respect to relationship-building questions, the direction and size of the effect is in line with our hypothesis, but the coefficient is slightly below the statistical significance level of 10 per cent (p-value of .105). Thus, it is difficult to interpret this result further.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Communication and empathy | Customer-focused decision-making | Openness to change and adaptability | Relationship building and community |

| Treat | 10.69** | 5.952 | 5.690 | 6.064 |

| (5.290) | (5.217) | (5.425) | (5.042) | |

| Treat * White | −11.02** | −5.357 | −7.569 | −4.045 |

| (5.499) | (5.429) | (5.630) | (5.267) | |

| White | 11.97*** | 9.865** | 14.04*** | 9.669*** |

| (3.905) | (3.883) | (4.062) | (3.652) | |

| Age category | −0.232 | 2.047 | 1.439 | −0.511 |

| (1.274) | (1.272) | (1.281) | (1.304) | |

| Male | −2.416 | −3.344** | −3.649** | −3.436** |

| (1.519) | (1.534) | (1.528) | (1.559) | |

| Constant | 41.84*** | 39.98*** | 38.23*** | 42.37*** |

| (4.512) | (4.458) | (4.696) | (4.289) | |

| Observations | 1,572 | 1,572 | 1,572 | 1,572 |

| R-squared | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.011 |

- Robust standard errors in parentheses.

- *** p < .01,

- ** p < .05,

- * p < .1.

- Note: This table presents difference in percentile scores by subject area on the test—the test questions are split into these four areas, so that there are five questions that pertain to each.

4 DISCUSSION

While public administration scholars have highlighted the challenge of government recruitment (Light 2000) and the promise of a representative bureaucracy (Selden 1997) for more than two decades, how to improve recruitment and selection in government is less clear. This study responds to Pitts and Wise's (2010) call for more ‘useable’ research on workforce diversity in the public sector by rigorously testing the impact of a low-cost nudge in police recruitment. Given the public policy importance of increasing diversity in the police, it is worthwhile to investigate every element of the recruitment and selection process from a behavioural perspective. This analysis looked at just one.

In this field experiment we used the principles around stereotype threat, belonging uncertainty and values affirmation to test the impact of making small changes to the email inviting candidates to take part in a Situational Judgment Test. This simple intervention, imposing neither selection risks nor significant costs, managed to increase the probability that a non-white applicant passed the SJT by 50 per cent, closing the gap in pass rates between non-white and white applicants who reached this stage in the process. The results suggest that reduced anxiety and feeling more comfortable with one's role in the community may be driving the results. The results also suggest that some other plausible mechanisms—such as motivation to take the test and time taken to complete the test—do not seem to be driving the effect. Given previous research suggesting that stereotype threat can be induced even without long-term historic stigma (Aronson et al. 1999), we also tested (ex-post) the impact of the intervention on gender. We did not find a statistically significant effect although, directionally, women in the treatment group fare better than women in the control group. That is, the probability of passing the test for women in the treatment group is 62 per cent, versus 59 per cent in the control group (p-value of .38). In contrast, the probability of passing the test for men in the treatment vs. control group is 57 per cent vs. 55 per cent, respectively (p-value of .67). These results match our expectations because this particular police force had many women in important and visible leadership positions, and because women—on average—performed better on these tests than men.1

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial measuring how small nuances in language can reduce stereotype threat during testing for public sector recruitment. Importantly, the intervention did not require extensive or frequent writing as do some other successful interventions (Harackiewicz et al. 2014). As a result, one contribution of our research is to demonstrate that even lighter-touch interventions can be effective if introduced at the appropriate time. While there are clear implications for other police forces aiming to increase the diversity of their force, this type of research should also have implications for other policy areas where the diversity of the workforce seems to pose a significant challenge not only for public managers but for the perceived legitimacy of the services delivered. Indeed, the results of this study should inform current policy debates around recruiting more diverse teachers (e.g., Boser 2011), city managers (e.g., Alozie and Moore 2007) or other frontline workers. Given that some oft-discussed policy alternatives range from lowering standards to implementing affirmative action initiatives—all of which have faced significant push back—this type of study also suggests that there are low-hanging fruit in improving current recruitment processes, which can operate alongside broader discussions on large policy shifts.

From a public management perspective, recommending that organizations employ a combination of different behavioural concepts to positively impact diversity in recruitment is appropriate. The social impact might be great, and the use of multiple behavioural concepts does not add operational costs to the entity's bottom line. However, given the surprisingly strong results of this study, future research should help determine the relative contribution of each change, and should iterate on the most effective components of the intervention. Of course, the ultimate question is whether getting more diverse candidates through this stage in the process will have knock-on effects in getting them both to be hired and to remain in the police force. This sample is too small to make that determination, but there does not seem to be a statistically significant effect on who passes through to the end of a lengthy assessment process.2 A related follow-up question is whether having a more diverse successful applicant pool affects who applies to join the police in the future. Ultimately, follow-up studies conducted in cooperation with larger police forces, where racial tensions may be more apparent, will help determine whether the results of our study apply more broadly. While the search to find large, system-wide improvements to selection and recruitment continues, this study suggests that there may be many simpler tools available for organizations to slightly alter testing and significantly support their applicants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Avon and Somerset Constabulary, particularly Chief Superintendent Steve Jeffries, Chief Superintendent Ian Wylie, Georgie Marriott, Catherine Dodsworth, Esther Wride and Annette Dowling, for their support and cooperation on this project, as well as the anonymous reviewers who have made this article significantly better.

APPENDIX A

Intervention messages

Control message

Dear $FirstName,

This message has been sent on behalf of $RecruiterName.

You have been invited to complete the following online assessment:

* Police Constable Situational Judgement Test.

Please be advised this stage of the assessment will close at $TimeDate.

Once the Situational Judgement Test has been completed you will not be contacted again until $TimeDate.

Please note there is no appeals process for this stage.

If you have any queries about why you have been asked to take the assessment, please contact the administrator at $RecruiterName.

The assessment website is compatible with the following Internet browsers:

[Technical specifications].

To access the assessment website, click on the link below. The first time you access the site you will be asked to set your password.

$CandidateUrl.

Your Username for accessing the site is: $Username.

Please retain this Username in case you need to re-access the website at a later point.

If you experience any technical difficulties in using the assessment website, check that your browser meets all of the requirements listed above. In the unlikely event that your browser meets these requirements but you still experience technical difficulties, please send an email to $AdministratorName.

Treatment message

Dear $FirstName,

Congratulations! You successfully completed the Behaviour Style Questionnaire and have been selected to participate in the next stage of the assessment process: the Situational Judgement Test.

Before you start the test, I'd like you to take some time to think about why you want to be a police constable. For example, what is it about being a police constable that means the most to you and your community?

When you're ready, you can access the assessment website here: [$CandidateUrl].

This online assessment will close at $TimeDate and we will contact you after $TimeDate to let you know whether you were successful.

Your Username for accessing the site is: $Username.

Please retain this Username in case you need to re-access the website at a later point.

The first time you access the site you will be asked to set your password.

If you have any difficulty accessing the assessment, please read the compatibility instructions at the bottom of this email. If you have any other queries, please do not hesitate to contact $AdministratorName.

Good luck!

$RecruiterName.

Recruitment Officer.

The assessment website is compatible with the following Internet browsers:

[Technical Specifications].

If you experience any technical difficulties in using the assessment website, check that your browser meets all of the requirements listed above. In the unlikely event that your browser meets these requirements but you still experience technical difficulties, please send an email to $AdministratorName.