Do Patients with Borderline Anemia Need Treatment before Total Hip Arthroplasty? A Propensity Score-Matched Cohort Study

Abstract

Objective

Preoperative anemia has been identified as a modifiable risk factor for multiple adverse outcomes. In real clinical practice, considering treatment of anemia would increase costs and delay surgery. Patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) with mild anemia are usually neglected and still underdiagnosed or inadequately treated. This study investigated the effects of preoperative borderline anemia and anemia intervention before THA on perioperative outcomes.

Methods

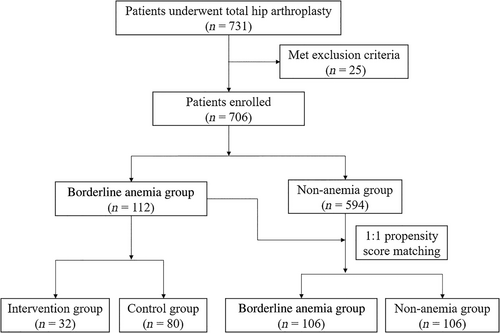

We screened 706 patients from those receiving THA at our hospital from January 2020 to January 2022, with 112 in the borderline anemia group and 594 in the non-anemia group. The cohort for this retrospective study was created by using propensity score matching (PSM) and subgroup analysis. The primary outcome was perioperative blood loss, while secondary outcomes were the rate of allogeneic blood transfusion and human serum albumin transfusion, perioperative laboratory indicators, postoperative length of stay, and complications. The independent sample t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to analyze continuous data, and the Pearson χ2-test or the Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables.

Results

After PSM, there was no significant difference in perioperative blood loss between patients in the borderline anemia group and the non-anemia group. The primary outcomes of hidden (p = 0.004) and total (p = 0.005) blood loss were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group. No statistical differences were found in allogeneic blood transfusion, human serum albumin transfusion, postoperative length of stay, or complications (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

Anemia treatments for patients with borderline anemia before THA significantly reduced hidden blood loss and total blood loss in the perioperative period and decreased the drop of hemoglobin and hematocrit without increasing postoperative complications.

Introduction

Preoperative anemia is extremely common in patients undergoing elective surgery. For major orthopaedic surgery, the prevalence can be as high as 26%,1 and the rate is even higher in the elderly.2 It has been identified as a modifiable risk factor for multiple adverse outcomes in the perioperative period, and researchers strongly recommend early detection and timely management of anemia before elective major surgery.1-4

As an elective surgery to address end-stage hip disease, 24% to 44% of patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) have variable degrees of preoperative anemia, which often leads to increased postoperative blood transfusion rates, complications, and prolonged length of stay if not managed properly.5-10 In real clinical practice, considering that screening and treatment of anemia would increase costs and delay surgery,5, 11 the preoperative interventions for anemia are mostly carried out for patients with severe anemia or even requiring blood transfusion, while those patients with mild anemia are usually neglected and still underdiagnosed or inadequately treated.

Therefore, we designed this retrospective cohort study focusing on patients with borderline anemia who had undergone THA in our hospital. We aimed to answer the following questions by using propensity score matching (PSM) and subgroup analysis: (i) whether patients with borderline anemia differ from non-anemia patients in postoperative outcome indicators; (ii) whether preoperative treatments in this subset of patients with borderline anemia would be of clinical benefit; and (iii) whether perioperative management can be further optimized to accelerate the recovery of THA patients. We focused on perioperative blood loss, allogeneic blood transfusion, postoperative laboratory indicators, complications, and postoperative length of stay.

Methods

Ethics Approval and Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study that was approved by our hospital's institutional review board (No. 20211463) and registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2100053888). Because the anonymous study was purely observational and harmless to patients, the institutional review board specifically granted a waiver of informed consent.

Patients who underwent primary unilateral THA by the same senior surgeon at our institution from January 2020 to January 2022 were considered for inclusion in this study. According to the World Health Organization diagnostic criteria for anemia,12 male patients with hemoglobin (Hb) <130 g/L and female patients with Hb <120 g/L were defined as anemia. In our hospital, elective surgery can be performed in patients with no significant active bleeding and Hb ≥100 g/L.13 Therefore, to explore whether there were differences in blood loss, blood transfusion, and postoperative complications between the patients who were anemic before primary unilateral THA but still tolerated surgery and non-anemia patients, we defined this group of patients as the borderline anemia group. In the borderline anemia group, preoperative Hb ranged from 100 ≤ Hb < 130 g/L in male patients and 100 ≤ Hb < 120 g/L in female patients. Because there were significant differences in baseline characteristics between the borderline anemia group and the non-anemia group of patients, we used 1:1 PSM.

We further conducted a subgroup analysis of patients in the borderline anemia group by reviewing electronic medical records for their medical orders at that time, based on whether or not they received preoperative anemia interventions, to investigate whether preoperative anemia interventions can benefit clinically. After admission, some borderline anemia group patients will be treated with drugs such as intravenous iron supplements and recombinant human erythropoietin (rHu-EPO) before surgery. For this study, the borderline anemia group was divided into an intervention group and a control group.

Patient Recruitment

Our patient inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) the patient had undergone primary unilateral THA by the same senior surgeon in our hospital; (ii) the patient had complete demographic and clinical data covering preoperative and 1 month after surgery; (iii) the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) functional status was I–III; and (iv) there were no serious organic diseases of important organs such as the heart, lung, and brain. Patients were excluded if they had (i) Hb value below 100 g/L; (ii) earlier hip surgery on the affected side; (iii) active inflammatory or infective disease, hematologic disorder, abnormal hemorrhage or abnormal coagulation function, and malignant diseases; and (iv) follow-up materials were incomplete.

Perioperative Management

After admission, the patients received perfected preoperative examinations to evaluate whether there were surgical contraindications. When we found the patients in a state of borderline anemia, the preoperative intervention measures were started. The type and model of the prosthesis were determined by taking a standard pelvis anteroposterior X-ray and ipsilateral femoral neck oblique radiography of the affected side. Before the operation, the same team of doctors and nurses instructed the patients to strengthen muscle training such as flexion and abduction of the hip joint on the affected side.

Routinely, tranexamic acid (15–20 mg/kg) was administered intravenously 30 min before skin incision, and the first-generation cephalosporin was administered intravenously at the same time to prevent infection. The patient was placed in a lateral position under general anesthesia, and THA was performed through a posterolateral approach by the same senior orthopaedic surgeon in our hospital. All patients used the cementless hip prosthesis (Depuy Synthes, New Brunswick, NJ, USA). During the operation, the surgeon thoroughly stopped bleeding and closed the incision layer by layer after flushing with normal saline. Based on some previous studies,14-16 a drainage tube was not routinely placed after the operation.

Because it takes time for preoperative interventions and blood mobilization to take effect, the borderline anemia patients usually had various degrees of anemia postoperatively as well, and therefore they often required further interventions. In contrast, for patients who did not receive an intervention preoperatively, we often choose whether or not to take an intervention postoperatively based on the results of a blood test on the first postoperative day. Antibiotics continue being administered until 24 h postoperatively. To prevent venous thromboembolism (VTE), low molecular weight heparin (0.2 mL) was administered beginning 12 h postoperatively and thereafter 0.4 mL every 24 h until discharge. When observing significant wound bleeding or subcutaneous bleeding, low molecular weight heparin was discontinued. Functional exercises were started on the day of surgery. Patients were discharged when they were able to ambulate independently with the walking aid and the incision had properly healed. After discharge, each patient was followed up regularly in the orthopaedic clinic, and their VTE prophylaxis regimen was changed to oral rivaroxaban (10 mg) once daily for 2 weeks.

Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Most of the data required for this retrospective study can be obtained through the electronic medical record system of our hospital, including (i) baseline characteristics of the patients, such as age, gender, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI); (ii) general clinical characteristics of the patients, such as ASA functional status, operation time, principal diagnosis, and comorbidities; (iii) postoperative length of stay, estimated intraoperative blood loss, and the rate of allogeneic blood transfusion and human serum albumin transfusion; and (iv) preoperative and postoperative Hb, albumin (Alb), and hematocrit (Hct). All preoperative data were collected prior to intervention with medications. Visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, and total blood loss were calculated using the formula.17, 18 Estimated intraoperative blood loss = the volume of liquid in the negative pressure suction device − the volume of flushing saline + the net weight gain of the gauze, which can be collected from the anesthetic records. Visible blood loss = estimated intraoperative blood loss + postoperative drainage volume. Total blood loss = the patient's blood volume × (preoperative Hct − postoperative Hct)/average of Hct, where the average of Hct is the mean of preoperative Hct and postoperative Hct. Hidden blood loss = total blood loss − visible blood loss. The incidence of postoperative complications was determined through outpatient service and scheduled telephone interviews.

Our primary outcome was perioperative blood loss, including estimated intraoperative blood loss, visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, and total blood loss. Secondary outcomes were the rate of allogeneic blood transfusion and human serum albumin transfusion, perioperative laboratory indicators, postoperative length of stay, and complications. Perioperative laboratory indicators included the Hb drop from preoperative to postoperative day (POD) 1 and the postoperative average Hb value during admission, preoperative and POD 1 Hb value, if available, Hb value on POD 3 and the postoperative average Hb value measured during admission, the same as Alb and Hct. Postoperative complications included wound oozing, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, venous thrombosis, prosthetic dislocation, periprosthetic fracture, and periprosthetic joint infection.

Propensity Score Matching

To best analyze the impact of preoperative borderline anemia on blood loss and reduce the bias from cohort selection, we used propensity score matching. The 1:1 PSM was performed using the nearest neighbor method with a standard caliper width of 0.20; cohorts of the preoperative borderline anemia group and the non-anemia group matched to the following variables were created: height, weight, BMI, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and osteoporosis. After matching the variables mentioned above, the difference between groups improved. Prior to matching, the borderline anemia group included 112 patients, and there were 594 patients in the non-anemia group. After 1:1 PSM, the final cohort included 106 patients in each study group (Fig. 1).

Statistical Analysis

We carried out all statistical analyses including PSM with SPSS 23.0 (IBM, New York, NY). Continuous variables were described using mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables were described using numbers (percentages). The independent sample t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test were used to analyze continuous data with normal and skewed distributions, respectively. The Pearson χ2-test or the Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables. The value of p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Results

Comparison of Borderline Anemia Group and Non-Anemia Group

From January 2020 to January 2022, we reviewed 731 patients, with 25 patients meeting the exclusion criteria, and finally 706 patients were eligible for the study (borderline anemia group, 112; non-anemia group, 594). Before matching, except for height, weight, BMI, principal diagnosis, and CKD and osteoporosis among the comorbidities (p < 0.05), there was no significant difference in other baseline characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Table 1). To reduce the bias from the baseline difference, we obtained 106 pairs of patients by 1:1 PSM (Fig. 1). After matching, there were only differences in gender, height, and one comorbidity between the two matched cohorts; the remaining comparisons were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

| Characteristic | Unmatched cohort (n = 706) | Matched cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borderline anemia group (n = 112) | Non-anemia group (n = 594) | p-value | Borderline anemia group (n = 106) | Non-anemia group (n = 106) | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 56.03 ± 14.85 | 54.43 ± 12.98 | 0.289 | 55.88 ± 14.80 | 55.36 ± 14.55 | 0.797 |

| Gender | 0.182 | <0.001* | ||||

| Women | 68 (60.71) | 320 (53.87) | 67 (63.21) | 101 (95.28) | ||

| Men | 44 (39.29) | 274 (46.13) | 39 (36.79) | 5 (4.72) | ||

| Height (cm) | 158.79 ± 9.16 | 160.91 ± 8.48 | 0.017* | 158.46 ± 9.17 | 155.95 ± 6.53 | 0.023* |

| Weight (kg) | 58.38 ± 9.21 | 62.42 ± 10.22 | <0.001* | 58.31 ± 8.67 | 57.73 ± 8.45 | 0.623 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.19 ± 3.43 | 24.07 ± 3.16 | 0.008* | 23.27 ± 3.30 | 23.76 ± 3.32 | 0.281 |

| Principal diagnosis | 0.008* | 0.207 | ||||

| ONFH | 37 (33.04) | 260 (43.77) | 0.035* | 34 (32.08) | 25 (23.58) | |

| DDH | 41 (36.61) | 210 (35.36) | 0.799 | 41 (38.68) | 49 (46.23) | |

| OA | 19 (16.96) | 95 (15.99) | 0.798 | 18 (16.98) | 24 (22.64) | |

| AS of hip | 8 (7.14) | 17 (2.86) | 0.025* | 7 (6.60) | 2 (1.89) | |

| RA of hip | 7 (6.25) | 12 (2.02) | 0.011* | 6 (5.66) | 6 (5.66) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 30 (26.79) | 146 (24.58) | 0.620 | 28 (26.42) | 27 (25.47) | 0.875 |

| DM | 10 (8.93) | 31 (5.22) | 0.124 | 7 (6.60) | 6 (5.66) | 0.775 |

| CHD | 20 (17.86) | 76 (12.79) | 0.152 | 19 (17.92) | 8 (7.55) | 0.023* |

| COPD | 2 (1.79) | 5 (0.84) | 0.685 | 2 (1.89) | 2 (1.89) | 1.000 |

| CKD | 5 (4.46) | 3 (0.51) | 0.002* | 1 (0.94) | 1 (0.94) | 1.000 |

| Osteoporosis | 47 (41.96) | 183 (30.81) | 0.021* | 45 (42.45) | 43 (40.57) | 0.780 |

| SLE | 2 (1.79) | 9 (1.52) | 1.000 | 2 (1.89) | 4 (3.77) | 0.679 |

| Gout | 2 (1.79) | 14 (2.36) | 0.979 | 1 (0.94) | 0 | 1.000 |

| ASA status | 0.062 | 0.162 | ||||

| I | 2 (1.79) | 8 (1.35) | 2 (1.89) | 2 (1.89) | ||

| II | 86 (76.78) | 504 (84.85) | 83 (78.30) | 91 (85.85) | ||

| III | 24 (21.43) | 82 (13.80) | 21 (19.81) | 13 (12.26) | ||

| Operation time (min) | 64.89 ± 17.12 | 65.63 ± 19.65 | 0.709 | 64.63 ± 17.44 | 65.44 ± 18.56 | 0.743 |

| Preoperative laboratory values | ||||||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 114.57 ± 7.56 | 141.52 ± 13.55 | <0.001* | 114.78 ± 7.50 | 125.43 ± 4.79 | <0.001* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 36.12 ± 2.52 | 43.10 ± 3.75 | <0.001* | 36.22 ± 2.54 | 38.79 ± 1.76 | <0.001* |

| Albumin (g/L) | 44.11 ± 2.85 | 46.24 ± 3.13 | <0.001* | 44.07 ± 2.85 | 45.77 ± 2.89 | <0.001* |

- Note: Values are given as n (%) or means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DDH, developmental dysplasia of the hip; DM, diabetes mellitus; OA, osteoarthritis; ONFH, osteonecrosis of the femoral head; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- * Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

There were no significant differences in estimated intraoperative blood loss, visible blood loss, hidden blood loss, total blood loss, and postoperative length of stay between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Table 2). Compared with the non-anemia group, the borderline anemia group had lower levels of preoperative Hb and Hct, POD 1 Hb and Hct, POD 3 Hb, and the postoperative average Hb and Hct value measured during admission (p < 0.05). The non-anemia group had significantly greater changes in Hb drop from preoperative to POD 1 than the borderline anemia group (20.37 ± 8.52 g/L vs. 14.73 ± 7.57 g/L, p < 0.001), the same as Hct drop and Alb drop. The Hb drop from preoperative to the postoperative average value during admission was significantly greater in the non-anemia group than in the borderline anemia group (22.50 ± 9.47 g/L vs. 17.59 ± 8.84 g/L, p < 0.001), the same as the Hct drop and Alb drop.

| Borderline anemia group (n = 106) | Non-anemia group (n = 106) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative blood loss (mL) | |||

| Estimated intraoperative blood loss | 107.92 ± 39.13 | 113.21 ± 40.74 | 0.337 |

| Visible blood loss | 113.59 ± 48.40 | 118.77 ± 52.00 | 0.454 |

| Hidden blood loss | 541.17 ± 326.51 | 587.99 ± 315.82 | 0.290 |

| Total blood loss | 654.77 ± 316.87 | 706.76 ± 315.31 | 0.232 |

| Postoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | |||

| Day 1 | 100.06 ± 9.43 | 105.07 ± 7.87 | <0.001* |

| Day 3 | 92.46 ± 11.22 | 98.07 ± 9.05 | 0.034* |

| Average during hospital stay | 97.19 ± 10.36 | 102.93 ± 8.50 | <0.001* |

| Hemoglobin drop (g/L) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 14.73 ± 7.57 | 20.37 ± 8.52 | <0.001* |

| Preoperative to postoperative average | 17.59 ± 8.84 | 22.50 ± 9.47 | <0.001* |

| Postoperative hematocrit (%) | |||

| Day 1 | 31.12 ± 2.85 | 32.28 ± 2.44 | 0.002* |

| Day 3 | 28.71 ± 3.22 | 30.21 ± 3.05 | 0.064 |

| Average during hospital stay | 30.29 ± 3.14 | 31.69 ± 2.72 | 0.001* |

| Hematocrit drop (%) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 5.09 ± 2.47 | 6.51 ± 2.53 | <0.001* |

| Preoperative to postoperative average | 5.92 ± 2.74 | 7.10 ± 2.77 | 0.002* |

| Postoperative albumin (g/L) | |||

| Day 1 | 37.37 ± 2.80 | 36.97 ± 2.85 | 0.304 |

| Day 3 | 36.16 ± 2.83 | 35.60 ± 2.36 | 0.425 |

| Average during hospital stay | 36.75 ± 2.91 | 36.46 ± 2.90 | 0.474 |

| Albumin drop (g/L) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 6.71 ± 3.02 | 8.80 ± 3.09 | <0.001* |

| Preoperative to Postoperative average | 7.32 ± 3.20 | 9.30 ± 3.17 | <0.001* |

| Postoperative length of stay (day) | 2.55 ± 1.02 | 2.55 ± 0.87 | 0.704 |

- Note: Values are given as means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviations: POD, postoperative day; PSM, propensity score matching.

- * Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The borderline anemia group and non-anemia group did not differ significantly in the incidence of human serum albumin transfusion, wound oozing, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, venous thrombosis, and prosthetic dislocation (Table 3). No patient developed periprosthetic fracture or periprosthetic joint infection, or required allogeneic blood transfusion within 1 month after surgery.

| Borderline anemia group (n = 106) | Non-anemia group (n = 106) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic blood transfusion | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Human serum albumin transfusion | 4 (3.77) | 3 (2.83) | 0.74 (0.16–3.40) | 1.000 |

| Wound oozing | 4 (3.77) | 5 (4.72) | 1.26 (0.33–4.84) | 1.000 |

| Urinary retention | 1 (0.94) | 1 (0.94) | 1.00 (0.06–16.20) | 1.000 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 (2.83) | 1 (0.94) | 0.33 (0.03–3.20) | 0.614 |

| Venous thrombosis | 1 (0.94) | 0 (0) | NA | 1.000 |

| Prosthetic dislocation | 1 (0.94) | 0 (0) | NA | 1.000 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Periprosthetic joint infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

- Note: Values are given as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; PSM, propensity score matching.

Subgroup Analyses of Borderline Anemia Group

The 112 patients in the borderline anemia group were divided into two subgroups according to whether preoperative intervention (intervention group, 32; control group, 80). There were no statistical differences between the intervention group and the control group in the baseline features, which included age, gender, height, weight, BMI, principal diagnosis, comorbidities, ASA status, and operation time (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Intervention group (n = 32) | Control group (n = 80) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 52.97 ± 15.33 | 57.25 ± 14.58 | 0.169 |

| Gender | 0.807 | ||

| Women | 20 (62.50) | 48 (60.00) | |

| Men | 12 (37.50) | 32 (40.00) | |

| Height (cm) | 158.00 ± 9.70 | 159.11 ± 8.98 | 0.564 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.99 ± 8.85 | 58.54 ± 9.40 | 0.776 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.36 ± 3.82 | 23.12 ± 3.29 | 0.737 |

| Principal diagnosis | 0.883 | ||

| ONFH | 12 (37.50) | 25 (31.25) | 0.525 |

| DDH | 11 (34.37) | 30 (37.50) | 0.756 |

| OA | 4 (12.50) | 15 (18.75) | 0.605 |

| AS of hip | 3 (9.38) | 5 (6.25) | 0.862 |

| RA of hip | 2 (6.25) | 5 (6.25) | 1.000 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 8 (25.00) | 22 (27.50) | 0.787 |

| DM | 4 (12.50) | 6 (7.50) | 0.637 |

| CHD | 5 (15.63) | 15 (18.75) | 0.907 |

| COPD | 1 (3.13) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| CKD | 2 (6.25) | 3 (3.75) | 0.942 |

| Osteoporosis | 15 (46.88) | 32 (40.00) | 0.505 |

| SLE | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.50) | 1.000 |

| Gout | 0 (0.00) | 2 (2.50) | 1.000 |

| ASA status | 0.288 | ||

| I | 1 (3.13) | 1 (1.25) | |

| II | 26 (81.25) | 60 (75.00) | |

| III | 5 (15.62) | 19 (23.75) | |

| Operation time (min) | 61.91 ± 16.15 | 66.09 ± 17.45 | 0.245 |

| Preoperative laboratory values | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 109.31 ± 7.08 | 116.68 ± 6.70 | <0.001* |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34.72 ± 2.44 | 36.67 ± 2.34 | <0.001* |

| Albumin (g/L) | 44.33 ± 3.26 | 44.02 ± 2.68 | 0.598 |

- Note: Values are given as n (%) or means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI, body mass index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DDH, developmental dysplasia of the hip; DM, diabetes mellitus; OA, osteoarthritis; ONFH, osteonecrosis of the femoral head; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

- * Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The primary outcomes of hidden (409.44 ± 267.05 mL vs. 601.52 ± 326.15 mL, p = 0.004) and total (529.78 ± 264.51 mL vs. 712.65 ± 314.73 mL, p = 0.005) blood loss were significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group, while no statistical difference was found in estimated intraoperative and visible blood loss (Table 5). Compared with the control group, the intervention group had lower levels of preoperative Hb and Hct (p < 0.001), while the preoperative Alb value was similar between these two groups (p = 0.598). No significant differences in postoperative Hb, postoperative Hct, postoperative Alb, and postoperative length of stay between the intervention group and the control group were detected (p > 0.05). The control group had significantly greater changes in Hb and Hct drop from preoperatively to postoperatively than the intervention group (p < 0.05), while the Alb drop was similar (p > 0.05).

| Intervention group (n = 32) | Control group (n = 80) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perioperative blood loss (mL) | |||

| Estimated intraoperative blood loss | 113.13 ± 44.32 | 106.50 ± 36.91 | 0.420 |

| Visible blood loss | 120.34 ± 53.41 | 111.13 ± 45.56 | 0.360 |

| Hidden blood loss | 409.44 ± 267.05 | 601.52 ± 326.15 | 0.004* |

| Total blood loss | 529.78 ± 264.51 | 712.65 ± 314.73 | 0.005* |

| Postoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | |||

| Day 1 | 96.91 ± 10.26 | 100.74 ± 8.92 | 0.052 |

| Day 3 | 90.60 ± 6.88 | 93.04 ± 12.37 | 0.460 |

| Average during hospital stay | 95.06 ± 9.96 | 97.68 ± 10.30 | 0.223 |

| Hemoglobin drop (g/L) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 12.41 ± 8.01 | 15.94 ± 7.00 | 0.023* |

| Preoperative to postoperative average | 14.25 ± 7.86 | 19.00 ± 8.59 | 0.008* |

| Postoperative hematocrit (%) | |||

| Day 1 | 30.59 ± 3.15 | 31.14 ± 2.72 | 0.363 |

| Day 3 | 28.60 ± 2.27 | 28.77 ± 3.50 | 0.889 |

| Average during hospital stay | 30.06 ± 3.15 | 30.25 ± 3.09 | 0.773 |

| Hematocrit drop (%) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 4.13 ± 2.35 | 5.54 ± 2.34 | 0.005* |

| Preoperative to postoperative average | 4.66 ± 2.21 | 6.42 ± 2.68 | 0.001* |

| Postoperative albumin (g/L) | |||

| Day 1 | 37.67 ± 2.84 | 37.17 ± 2.76 | 0.395 |

| Day 3 | 35.33 ± 3.34 | 36.44 ± 2.56 | 0.307 |

| Average during hospital stay | 36.95 ± 3.09 | 36.64 ± 2.80 | 0.610 |

| Albumin drop (g/L) | |||

| Preoperative to POD 1 | 6.67 ± 3.17 | 6.85 ± 2.95 | 0.775 |

| Preoperative to Postoperative average | 7.38 ± 3.32 | 7.38 ± 3.12 | 0.992 |

| Postoperative length of stay (day) | 2.59 ± 1.13 | 2.59 ± 1.06 | 0.828 |

- Note: Values are given as means ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviation: POD, postoperative day.

- * Statistically significant (p < 0.05).

The intervention group and control group did not differ significantly in the incidence of human serum albumin transfusion, wound oozing, urinary retention, nausea and vomiting, venous thrombosis, and prosthetic dislocation (Table 6). No patient developed periprosthetic fracture or periprosthetic joint infection or required allogeneic blood transfusion within 1 month after surgery.

| Intervention group (n = 32) | Control group (n = 80) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allogeneic blood transfusion | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Human serum albumin transfusion | 0 (0) | 4 (5.00) | NA | 0.577 |

| Wound oozing | 0 (0) | 4 (5.00) | NA | 0.577 |

| Urinary retention | 0 (0) | 2 (2.50) | NA | 1.000 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 2 (6.25) | 1 (1.25) | 5.27 (0.46–60.24) | 0.405 |

| Venous thrombosis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.25) | NA | 1.000 |

| Prosthetic dislocation | 1 (3.13) | 1 (1.25) | 2.55 (0.16–42.02) | 1.000 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Periprosthetic joint infection | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

- Note: Values are given as n (%)unless otherwise noted.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort study, by using PSM and subgroup analysis, we explored the effects of preoperative borderline anemia and medical treatment before surgery on perioperative blood loss, allogeneic blood transfusion, postoperative laboratory indicators, and complications in patients undergoing THA. Our results suggest that patients with borderline anemia should be actively treated before surgery to improve anemia, which can significantly reduce hidden blood loss and total blood loss and decrease the drop of Hb and Hct, and that this intervention has no adverse effect on postoperative complications.

Preoperative Treatment of Borderline Anemia Can be Clinically Beneficial

Among all causes of anemia, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is still the most common type of anemia worldwide.19 Iron supplementation is the preferred treatment for IDA, and intravenous iron is preferred for patients planning to undergo surgery in the short term, which increases iron stores for erythropoiesis and reduces transfusion rates.1-3 Preoperative administration of erythropoietin (EPO) for the treatment of anemia is also recommended in elective major orthopaedic surgery, which is responsible for the stimulation and maturation of red blood cells in the bone marrow.2, 3 In a prospective, nonrandomized study of primary THA and total knee arthroplasty, Bedair et al. found that20 preoperatively taking treatment significantly reduced transfusion rates and decreased the postoperative Hb drop in patients. Muñoz et al. also found this intervention to be safe and effective.21 Similar to the previous treatments in our hospital, patients included in the intervention group in this study were given intravenous iron and subcutaneous short-acting EPO. The average preoperative iron supplementation was 283 mg and the EPO dosage was 30,400 units. We also found that patients in the intervention group had significantly lower perioperative blood loss and lower postoperative Hb drop than the control group, and no patient developed any complications feared by some investigators, such as allogeneic blood transfusion and venous thrombosis.3 Such results need to be validated in studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods.

Patients with Borderline Anemia Are Not Significantly Disadvantaged for Total Hip Arthroplasty

In addition, our study found that the difference in perioperative blood loss between the borderline anemia group and non-anemia group was small and did not reach statistical significance. This may be limited by the PSM we performed. Interestingly, we also detected that the postoperative drop of Hb, Hct, and Alb was significantly greater in the non-anemia group than in the borderline anemia group, while the postoperative values of these indicators were still statistically different between the two groups, but the difference was decreasing compared to the preoperative values. We considered that it was due to the gender difference between the two groups in this study, with women accounting for 63% of the borderline anemia group and 95% of the women in the non-anemia group (Table 1). Several studies have revealed that women have lower circulating blood volumes and a lower number of red blood cells compared with men but have comparable blood loss when undergoing specific operations, which often leads to higher relative red blood cell mass loss and transfusion rates in women.1, 4, 19, 22, 23 Furthermore, some studies in obstetrics and gynecology have found that there is not a strong correlation between perioperative blood loss and change in preoperative to postoperative Hb,24, 25 and the two are significantly correlated only when the perioperative blood loss exceeds some cut-off value,26 which suggests that perioperative blood loss as a quality indicator in studies should be used with caution.25 Unfortunately, there are poorly relevant studies in orthopaedic, which need to be investigated in future work.

Strengths and Limitations

By utilizing PSM and subgroup analysis, it was found that preoperative interventions can be clinically beneficial. PSM reduces confounding bias, makes the two groups comparable, and ultimately brings the level of evidence for the results as close as possible to the randomized controlled trial. Our study is a positive contribution to future clinical practice to optimize the perioperative management of patients undergoing THA. However, there are few studies in orthopedics that have explored the above issues. First, the reduced number of patients in our cohorts and gender differences remain shortcomings of this study. A multicenter, large-sample, prospective study is needed to further verify these findings. Second, we selected patients with Hb ≥100 g/L as research subjects, which may differ from other hospitals and limit the generalizability of these findings. Third, the present study did not incorporate other anemia treatments, and future studies should test the applicability of our findings to other treatments.

Conclusions

By using PSM and subgroup analysis, we found that anemia treatments for patients with borderline anemia before THA significantly reduced hidden blood loss and total blood loss in the perioperative period and decreased the drop of hemoglobin and hematocrit without increasing postoperative complications. In addition, the difference in perioperative blood loss between the borderline anemia patients and non-anemia patients was small and did not reach statistical significance. Interestingly, the postoperative drop of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and albumin was significantly greater in the non-anemia patients than the borderline anemia patients. Better perioperative management of THA and enhanced recovery after surgery require further investigation in clinical practice and research.

Author Contributions

All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors are in agreement with the manuscript. CLJ was responsible for material preparation, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing. CLYL, ZCC, HGT, and WQR were responsible for data collection. KPD was responsible for the study design and correspondence. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our sincere appreciation to all the patients who joined this study. This study was supported by the 1·3·5 Project for Disciplines of Excellence–Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (grant no. ZYJC18040).

Ethics Statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Clinical Trials and Biomedical Ethics Committee of Sichuan University West China Hospital (no. 20211463). Due to the anonymous study being purely observational and harmless to patients, the institutional review board specifically granted a waiver of informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.