Reducing the risk of HIV transmission among men who have sex with men: A feasibility study of the motivational interviewing counseling method

Abstract

HIV prevalence among Chinese men who have sex with men has rapidly increased in recent years. In this randomized, controlled study, we tested the feasibility and efficacy of motivational interviewing to reduce high-risk sexual behaviors among this population in Changsha, China. Eighty men who have sex with men were randomly assigned to either the intervention group, in which participants received a three-session motivational interviewing intervention over 4 weeks, or the control group, in which participants received usual counseling from peer educators. High-risk behavior indicators and HIV knowledge level were evaluated at baseline and 3 months after the intervention. Motivational interviewing significantly improved consistent anal condom use. However, there was no significant change in consistent condom use for oral sex or in the number of sexual partners over time. HIV knowledge scores improved equally in both groups. This study demonstrated that an intervention using motivational interviewing is feasible and results in increased condom use during anal sex for Chinese men who have sex with men. However, further work must be done to increase the use of condoms during oral sexual encounters.

Introduction

In recent years, the sexual transmission of HIV in China has increased among men who have sex with men (MSM). New cases attributed to MSM rose from 2.5% in 2006 to 21.4% in 2013. HIV prevalence among MSM increased from 1.4% in 2005 to 7.3% in 2013 (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China's, 2014). Therefore, the prevention of new HIV infections among MSM has become one of the primary focuses of the Chinese public health agenda. Reducing high-risk sexual behavior among MSM is a primary strategy for achieving HIV reduction.

Literature review

The underlying reason for the rapid spread of HIV among MSM is the high frequency of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) among multiple sexual partners. A meta-analysis indicated that only 36.3% of MSM consistently used condoms during anal intercourse over the past 6 months in China (Chow et al., 2012), and the average number of sexual partners during the past 6 months among Chinese MSM was approximately six (Zhang et al., 2012). In addition, another recent meta-analysis showed that 26% of MSM also had female sexual partners during the past 6 months, and only 26% consistently used condoms during heterosexual contact (Chow et al., 2011). Unprotected oral sex was also highly prevalent among Chinese MSM, with evidence showing that 80% of MSM had oral sex during the previous 6 months, with 56% never using a condom (Ma et al., 2015). Unfortunately, it has been confirmed that HIV can be transmitted through oral sex (Gilbart et al., 2004).

Successfully reducing high-risk sexual behaviors among MSM is an important strategy for controlling the HIV/AIDS epidemic and lowering the incidence of HIV and sexually-transmitted diseases. However, interventions targeted at reducing high-risk behaviors among MSM face great challenges in China, including insufficient HIV surveillance among MSM, a high-level of social stigma toward homosexuality, a lack of governmental financial support and collaboration with community-based organizations, and limited capacity of peer educators (Chow et al., 2014).

Experts have proposed four intervention models in China to reduce high-risk sexual behavior among MSM: (i) health education and communication with friends; (ii) peer education; (iii) interventions delivered at MSM venues; and (iv) health counseling (Zhang et al., 2009). However, to date, HIV transmission among MSM has not decreased (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China's, 2014).

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a counseling approach that was developed by Miller and Rollnick in the 1980s to treat alcoholism, and has been used widely to treat lifestyle-related problems and disease management. The philosophy of this therapy is to elicit and enforce the client's intrinsic motivation so that change arises from within, rather than being imposed externally (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). MI has been translated into 40 languages, and is widely used in different areas (Miller & Rollnick, 2009). The effectiveness of MI has been reported among varying populations, settings, and problems (Lundahl & Burke, 2009; Lundahl et al., 2010; Miller & Rollnick, 2014). For example, several meta-analyses found that MI was effective in changing smoking behavior (Lindson-Hawley et al., 2015), drug use (Smedslund et al., 2011), and gambling (Gooding & Tarrier, 2009), and has demonstrated benefits on clinical outcomes, such as HIV viral load and mortality (Lundahl et al., 2013).

Results have been mixed for the efficacy and effectiveness of MI to reduce UAI among MSM. Naar-King et al. (2012) systematically reviewed six randomized, controlled trials (RCT) targeting high-risk sexual behaviors among HIV-positive adults and found that MI had the potential to reduce high-risk sexual behaviors. Similar results were reported by Rongkavilit et al. (2015), who found that MI could significantly reduce UAI among HIV-positive youth. However, Berg et al. (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of 10 RCT and found an insignificant difference between MI interventions and other educational interventions.

Miller and Rollnick (2014) recently commented that the efficacy of MI was influenced by providers' training backgrounds and fidelity of the treatment intervention, with the exception of sociocultural factors (i.e. ethics, age, sex). They recommended that providers be competently trained to deliver MI, and that the counseling be recorded and coded according to a guiding process (i.e. Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity [MITI] 3.1.1), including both the providers' and clients' responses.

Unfortunately, no randomized, controlled studies testing the feasibility and efficacy of MI have been conducted among Chinese MSM. It is not known whether this technique can be applied in China among MSM and if it will efficiently reduce high-risk sexual behaviors in the Chinese context.

Study aim

The aims of this RCT were to test the: (i) feasibility of using the MI counseling method to recruit and retain MSM; (ii) feasibility of maintaining the fidelity of the MI intervention; and (3) efficacy of MI on reducing high-risk sexual behaviors and improving HIV/AIDS awareness among MSM in a Chinese cultural context.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Potential participants who visited a non-government organization (NGO) (Zuo An Cai Hong, Changsha, Hunan, China) for MSM in Changsha, Hunan, China, for HIV counseling and testing were invited by a trained peer educator to participate in the study, which ran from August 2011 to April 2012. The NGO collaborates with the Changsha Centers for Disease Control to conduct outreach and voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) programs among MSM in Changsha. Participants enrolled in this study were required to meet the following criteria: (i) 16 years of age or older; (ii) self-reported at least one high-risk sexual behavior during the past 3 months, including unprotected anal or oral sex with men, or having two or more sexual partners; (iii) self-reported a negative HIV test or unknown HIV status at time of entry into study; and (iv) self-reported no plans to leave the city during the subsequent 4 months of the study.

Potential participants were introduced to the study purpose and procedures by a trained peer counselor. After obtaining written, informed consent, all participants were administered the entry questionnaire, which was used to collect demographic and sexual behavior-related characteristics (Table 2), and sexual practice and HIV knowledge by two trained research assistants (Table 3). They were then randomized to either the MI or control group through a randomization table. Participants in the MI group were referred to a separate room in the NGO, where they had the first intervention interview with the interventionists (the second and fourth authors); the subsequent two MI sessions were scheduled within 1 month for scheduling flexibility. The interventionists could seek consultation from peer educators, but these encounters were not scheduled in this study. Participants in the control group were referred to another room, where they received usual education (including the importance of condom use and protection) and consultation from a peer educator.

Two weeks immediately prior to the fourth month, the peer counselor called each participant to make an appointment for the follow-up study visit, during which time a follow-up questionnaire was administrated to evaluate the participants’ sexual practice and HIV knowledge by two research assistants who were blinded to the participant's group randomization. All participants received a box of condoms and a bottle of lubricant (valued at approximately US $4.00) as compensation for transportation and time.

The study was approved by the Research Ethical Committee of Xiangya Nursing School, Central South University (Changsha Hunan, China). There was no research ethical committee for the NGO. All the paper materials, including the written, informed consent, transcripts of the audio-recorded interviews, and questionnaires, were locked in a separate drawer. The electronic database and audio-recorded interviews were stored in a private computer with codes for each file. The participants were anonymous to all researchers. Only the peer counselor had the participants' contact information (but not necessarily their real names). Confidentiality was also confirmed during the intervention process.

MI intervention

Two authors with training in MI skills delivered the MI intervention. Each session averaged approximately 60 min in length (range: 40–90 min). The MI intervention focused on evoking “change talk” by using the core skills of open questions, affirmation, reflections, and summary (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The main-goal-and-skills-for-change talk for each session are outlined in Table 1. The interviews for the first four sessions of each interventionist were audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded according to the MITI code by the first and third authors (Moyers et al., 2003). Fidelity was discussed with the interventionists to ensure the interviews adhered to MI principles. The research team met biweekly to discuss the intervention and data collection separately.

| Session | Main goal of MI | Main skills | Examples of open-ended questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | 1. Identify discrepancies between the client's current and ideal situation | 1. Express empathy | 1. Could you tell me something about your current sexual life? |

| 2. Elicit the intrinsic motivation to change | 2. OARS (open question and reflection most important) | 2. What concerns do you have about your current sexual behavior? | |

| 3. Decision balance table | 3. What would be your ideal sexual life? | ||

| 4. Information supplementation (correcting misbelief about HIV and prevention skills) | 4. To what extent do you want to change your current behavior (using the ruler)? For example, why do you say a six, not a three (making sure to give the larger number first)? | ||

| 5. Ruler for change importance assessment, and followed probing questions. | |||

| Session 2 | 1. Help the participant set up strategies to overcome barriers to change | 1. Express empathy | 1. I absolutely understand your situation. However, do you consider your health risk (or your family responsibility) when…? |

| 2. Elicit self-efficacy for change | 2. Roll with the resistance. | 2. What kinds of strategies have you used to change high-risk sexual behavior since we met last? | |

| 3. OARS (refection and summary most important) | 3. How do you evaluate those strategies? | ||

| 4. Ruler for preparation and self-efficacy assessment, and followed probing questions | |||

| 5. Good example of peers to deal with barriers as supplementation | |||

| Session 3 | 1. Help the participant maintain self-efficacy and action to change | 1. Supporting self-efficacy | 4. What are the barriers and facilitators to changing your current sexual behaviors? |

| 2. Help develop alternative coping strategies for unique emotional or structural barriers | 2. OARS (open question and affirmation most important) | 5. Some people have told me they use (a particular kind of strategy)…what do you think about this strategy for you? | |

| 3. Ruler for self-efficacy assessment, and followed probing questions | 6. How much confidence do you have that you will be able to consistently use condoms in future (using the ruler)? For example, why do you say a six not a three (making sure to give the larger number first)? | ||

| 4. Alternative information supplementation regarding specific barriers |

- MI, motivational interviewing; OARS, open questions, affirmation, reflection, and summary.

Variables and their measurement in the questionnaire

Demographic variables, such as age, ethnicity, residence, education, marital status, employment, monthly income, and cohabitation situation, were included in the entry questionnaire. Sexual behavior-related characteristics included sexual orientation and the sex of sexual partners during past 3 months. Whether the participants knew someone who was HIV positive was also investigated.

Outcome variables in both the entry and follow-up questionnaires included consistent condom use for both anal and oral sex during the past 3 months, regardless of whether receptive or insertive; the number of sexual partners during the past 3 months; and HIV-related knowledge. HIV-related knowledge was measured with a 10-item HIV knowledge scale tested in a previous study among MSM in Chengdu, China, and covered knowledge of transmission routes, treatment efficacy, and China's Four Free and One Care policy (free HIV counseling and screening, free antiretrovirus treatment, free intervention for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, free education for AIDS orphans, and economic assistance to families living with HIV) (Liu et al., 2010). The responses given were “true” or “false”. The correct answer was calculated as a score of one, so the total knowledge score continually ranged from zero to 10, with a higher score representing a higher HIV knowledge level. The content validity in the original study was 0.86 (Liu et al., 2010), and the reliability in this study was 0.92 using the KR-20, a statistical method to test internal consistency reliability for measures with dichotomous choices.

Data analysis

Data were double entered into Excel by researchers blinded to the randomization. Descriptive and bivariate analyses were carried out using χ2-test and Kruskal–Wallis test. Mixed logistic regression (xtlogit random-effects model) was used to model changes over time by group for binary outcome variables; for the continuous outcome variable of HIV knowledge, multilevel mixed-effects linear regression was used to model changes over time by group. Analyses were performed in Stata (version 12.0; College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Participant flow

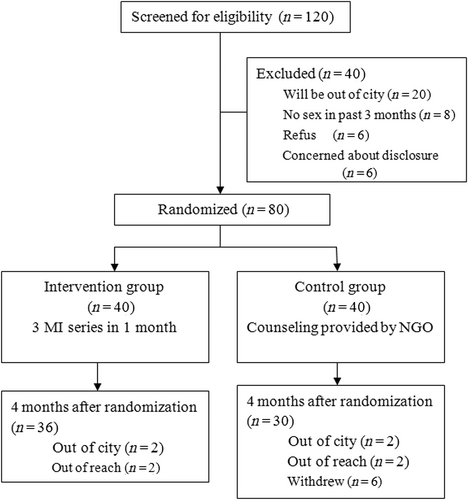

A total of 120 participants were invited to participate in this study, one-third of whom were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was not planning to remain in Changsha for the subsequent 4 months (n = 20). Eighty participants were randomized into the two groups (n = 40 in each group). During the 4 months of the study, four participants in the intervention group and 10 participants in the control group were lost to follow up (Fig. 1). There was an insignificant trend in attrition (χ2 = 3.12, P = 0.08).

Participant characteristics

The average age of the participants was 22 (standard deviation [SD] = 5, range: 16–44) years. Most were Han nationality (93%), born in an urban area (76%), and had a college-level or higher-education background (80%); approximately half (54%) were current college students. Twenty percent self-reported as bisexual, while 23% had had sex with both males and females in the past 3 months. Most (91%) did not know any HIV-positive people. The distribution of the characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the two groups.

| Control | Intervention | χ2 (Fisher's exact test) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Age (years) | 2.738 | 0.254 | ||||

| <20 | 6 | 15.0 | 3 | 11.3 | ||

| 20-24 | 29 | 72.5 | 27 | 70.0 | ||

| ≥25 | 5 | 12.5 | 10 | 18.7 | ||

| Han nationality | 0.721 | 0.396 | ||||

| 0 = No | 4 | 10.0 | 2 | 5.0 | ||

| 1 = Yes | 36 | 90.0 | 38 | 95.0 | ||

| Urban | 1.726 | 0.189 | ||||

| 0 = No | 7 | 17.5 | 12 | 30.0 | ||

| 1 = Yes | 33 | 82.5 | 28 | 70.0 | ||

| Education | 1.077 | 0.783 | ||||

| Middle school or lower | 2 | 5.0 | 1 | 2.5 | ||

| High school/vocational school | 6 | 15.0 | 7 | 17.5 | ||

| College or higher | 32 | 80.0 | 32 | 80.0 | ||

| Marital status | 1.386 | 0.500 | ||||

| Single/no regular partner | 37 | 92.5 | 39 | 97.5 | ||

| Legally married | 2 | 5.0 | 1 | 2.5 | ||

| Divorced or widowed | 1 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Employment | 1.352 | 0.717 | ||||

| Unemployed | 3 | 7.5 | 4 | 10.0 | ||

| Temporarily employed | 1 | 2.5 | 3 | 7.5 | ||

| Stably employed | 13 | 32.5 | 13 | 32.5 | ||

| Student | 23 | 57.5 | 20 | 50.0 | ||

| Income per month (USD) | 6.167 | 0.290 | ||||

| No income | 19 | 47.5 | 17 | 42.5 | ||

| <=170 | 3 | 7.5 | 5 | 12.5 | ||

| 170.1–340 | 6 | 15.0 | 6 | 15.0 | ||

| 340.1–500 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 12.5 | ||

| 500.1–670 | 1 | 2.5 | 5 | 12.5 | ||

| > = 670.1 | 7 | 17.5 | 2 | 5.0 | ||

| Living arrangement | 6.652 | 0.248 | ||||

| Live alone | 4 | 10 | 9 | 22.5 | ||

| Live with family (including wife) | 11 | 27.5 | 9 | 22.5 | ||

| Live with a homosexual partner | 5 | 12.5 | 3 | 7.5 | ||

| Live with a homosexual friend | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 5.0 | ||

| Live with a heterosexual friend | 2 | 5.0 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Live with classmate(s) | 18 | 45.0 | 17 | 42.5 | ||

| Sexual orientation | 0.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Homosexual | 28 | 70.0 | 28 | 70.0 | ||

| Bisexual | 8 | 20.0 | 8 | 20.0 | ||

| Do not know | 4 | 10.0 | 4 | 10.0 | ||

| Sexual behavior | 6.731 | 0.151 | ||||

| Have sex with men and women | 10 | 25.0 | 8 | 20.0 | ||

| Have sex only with men | 30 | 75.0 | 32 | 80.0 | ||

| Know someone with HIV | 4.014 | 0.134 | ||||

| No | 37 | 92.5 | 36 | 90.0 | ||

| Yes, but not acquainted with them | 3 | 7.5 | 1 | 2.5 | ||

| Yes, acquainted with them | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 7.5 | ||

Changes in high-risk sexual behavior over time

At baseline, only 35% of those in the control group and 45% of those in the MI group reported consistently using condoms during anal intercourse in the past 3 months (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the two groups at baseline (χ2 = 0.83, P = 0.36). After the intervention, the rate for consistent condom use during anal sex increased in the MI group and dropped in the control group. The mixed logistic regression model showed that the intervention group at follow up was 5.7 times likely to use condoms consistently compared to everyone at baseline (P = 0.006, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.63–20.2). At follow up, the control group was 0.42 times likely to use condoms consistently, but this was not statistically significant (P = 0.176, 95% CI: 0.12–1.48) (Table 4).

| Pre-intervention | Post-intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group (n, %) | MI group (n, %) | P-value | Control group (n, %) | MI group (n, %) | P-value | |

| Consistent condom use during anal sex | 0.36 | 0.01 | ||||

| No | 26 (65.0) | 22 (55.0) | 20 (74.1) | 8 (27.6) | ||

| Yes | 14 (35.0) | 18 (45.0) | 7 (25.9) | 21 (72.4) | ||

| Consistent condom use during oral sex | – – | 0.96 | ||||

| No | 40 (100) | 39 (100) | 24 (85.7) | 25 (86.2) | ||

| Yes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (14.3) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| No. sexual partners | 0.17 | 0.46 | ||||

| 2+ | 6 (15.0) | 11 (27.5) | 7 (22.6) | 11 (42.3) | ||

| 1 or none | 34 (85.0) | 29 (72.5) | 24 (77.4) | 15 (57.7) | ||

| HIV knowledge score | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | 0.20 | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | 0.04 |

| 6.00 (2.23) | 6.25 (2.08) | 6.52 (2.11) | 7.53 (1.84) | |||

- MI, motivational interviewing; SD, standard deviation.

| Random-effects logistic regression (xtlogit) model for consistent condom use for anal sex | Multilevel mixed-effects linear regression model for HIV knowledge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-value | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Co-efficient | 95% CI | ||

| Baseline (control and MI groups) | – – | Ref | – – | Group | 0.17 | 0.63 | -0.28, 1.53 |

| Control group at post-intervention | 0.176 | 0.42 | 0.12, 1.48 | Time | 0.06 | 0.64 | 0.01. 1.30 |

| MI group at post-intervention | 0.006 | 5.74 | 1.63, 20.2 | Group#time | 0.71 | 0.17 | –0.73, 1.08 |

| χ2/F | 9.67 | 13.52 | |||||

| P-value | 0.008 | 0.004 | |||||

- CI, confidence interval; MI, motivational interviewing; OR, odds ratio.

There was no change in condom use for oral sex after the intervention (χ2 = 1.12, P = 0.96) (Table 3). At baseline, no one consistently used condoms during oral sex in the past 3 months. After the intervention, four participants in each group reported consistently using condoms for oral sex (Table 3).

With regard to the number of sexual partners, at baseline, 15% of those in the control group and 28% in the MI group had two or more sexual partners during the previous 3 months (χ2 = 1.88, P = 0.17) (Table 3). The MI intervention group did not differ from the control group in reducing the number of sexual partners during follow up (χ2 = 1.24, P = 0.46) (Table 3).

Changes in HIV knowledge over time

The average HIV knowledge score was six (SD = 2) for the control group and seven (SD = 2) for the MI group at baseline (Table 3). There was no significant difference between the two groups at baseline (H = –1.30, P = 0.20). The mean HIV knowledge score increased from baseline to post-intervention in both groups, but the increase was not statistically significant. (P = 0.06) (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of an MI strategy targeting reducing high-risk sexual behaviors among Chinese MSM. This small, RCT shows that a brief three-session MI was feasible and significantly reduced UAI among MSM over time in a Chinese context.

Of note, in this study, one-third of those screened were excluded due to an unwillingness to meet the criterion of remaining in the city during the study period. Remaining in the city might have been a barrier to participation. However, there is anecdotal evidence that this could have been a polite way of declining to be in the study. This is consistent with other studies that found also had difficulty recruiting MSM for HIV-related studies. Jenkins (2012) summarized a panel discussion on MSM recruitment barriers in 2009. Possible recruitment barriers included perceived low HIV risk and severity of HIV infection, a diminished sense of community, and research fatigue. In addition, in China it is difficult to retain MSM in longitudinal or RCT studies due to severe stigmatization and discrimination against them. However, the lost-to-follow-up rate in our study was similar to those of other longitudinal studies carried out among MSM in China (Ruan et al., 2009; Yan et al., 2012).

UAI is a primary cause of HIV transmission among MSM. Our study showed that MI can significantly improve condom use for anal intercourse. This is consistent with a large, multisite behavioral prevention intervention based on MI among young MSM living with or without HIV in the USA (Chen et al., 2011; Parsons et al., 2014). According to Miller and Rollnick's (2014) recommendation, the interventionists in the present study were thoroughly trained in counseling techniques. The interviews were conducted according to MITI codes to assure intervention fidelity.

Unfortunately, the study did not demonstrate any influence on reducing the frequency of unprotected oral sex. At baseline, no one consistently used condoms during oral sex. Informal discussions during the biweekly research team meetings indicated that many MSM had never heard about using condoms during oral sex as a means of HIV prevention, as the national 100% condom-promotion program mainly focuses on anal condom use (Zheng & Zheng, 2012). The participants described significant barriers to using condoms for oral sex, including that they did not like the flavor, found they were difficult to buy, did not believe that they were needed for oral sex, and that their friends did not use oral condoms. An Internet-based information intervention in Thailand also showed that it was very difficult to increase condom use during group and individual oral sex among MSM (Kasatpibal et al., 2014).

It was not unexpected that HIV knowledge improved equally over time in both groups, because the goal of MI is not to increase knowledge more than that provided by peers, but rather to reduce high-risk sexual behavior.

Our study has several limitations. First, our sample did not include MSM who never visited the NGO for HIV counseling or testing, which affected the generalizability of the findings. Second, in order to retain people in the study and reduce selection bias, we did not require that all interviews be recorded; however, this might have created other biases, such as ascertainment bias. To counter this, we had a strict process for the coding of the first four sessions and a clear intervention protocol to ensure intervention fidelity. Third, we only had one time-point evaluation after the intervention; therefore, the longer time efficacy of MI to reduce UAI among Chinese MSM was unclear.

Acknowledging these limitations, there remain important implications and recommendations for practice and future studies. First, MI could be integrated into VCT centers to reduce high-risk sexual behaviors among Chinese MSM. MI counseling skills offer promising opportunities for improving the effectiveness of the behavior intervention delivered by healthcare providers and peer educators who are working in VCT centers. Second, the fidelity of the MI process must be assured when training MI providers. To do this, this study's protocol could be generalized in future practice and studies. Third, the “100% Condom Use Intervention Program among MSM” implemented by the Chinese Government should emphasize condom use for oral sex, as well as for anal sex (Ma et al., 2015).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that it is feasible to recruit and retain participants in an MI intervention, and that an MI intervention can be successful in the MSM community setting, as long as the fidelity of the MI intervention quality and procedure are guaranteed. The generalizability and the long-term effectiveness of MI conducted by trained healthcare providers or peers to improve consistent condom use during anal or oral sex among MSM need to be evaluated in future studies in China.

Acknowledgement

This study was originally supported by the “Freedom Explore Program of Central South University (2011QNZT243)”, and partly supported by “Projects of the National Social Science Foundation of China (15CSH037)”. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the two college volunteers as research assistants who collected the data, the peer educator who facilitated the study procedure, the organizers in Zuo An Cai Hong in Changsha, and all the study participants.

Contributions

Study Design: XL, AW

Data Collection and Analysis: JC, XL, YX, WZ, KF, XL

Manuscript Writing: JC, XL, AW, KF