Investigation of mental health in Indonesian health workers immigrating to Japan under the Economic Partnership Agreement

Abstract

The aim of this study was to assess the mental health status of Indonesian nurses and care workers who immigrated to Japan after the Economic Partnership Agreement was signed by the governments of Japan and Indonesia in 2008. From November 2012 to March 2013, questionnaires were mailed to 206 workers in 87 medical and caregiving facilities that openly accept Indonesian EPA immigrant workers. Responses were received from 71 workers in 35 facilities. Responses from 22.5% of workers suggested that they were at risk of developing mental health problems, and “gender” and “acquisition state of national qualifications” were the main factors influencing their mental health status. The results suggest that support after obtaining national qualifications is inadequate and that mid and long-term support systems that focus on the needs of immigrant healthcare workers after passing national examinations are necessary.

Introduction

Since the mid-1990s, there has been a rapid increase in the international movements of medical and healthcare workers, primarily doctors and nurses. In addition to the general acceleration of movement across borders as a result of globalization, the declining birthrate and aging population in developed countries has increased the demand for workers in the medical, nursing, and nursing-care fields (Sato, 2009; International Council of Nurses, 2013). Nurses from developing countries are attracted by educational and training opportunities, salaries far higher than they can earn at home, and seemingly comfortable living conditions (International Centre on Nurse Migration, 2008). The International Council of Nurses (ICN; 2007) states that nurses in all countries have the right to migrate by choice, regardless of motivation. However, at the same time, the ICN acknowledges that international migration may negatively affect the quality of health care in regions or countries with serious depletion of their nursing workforce. International movement of healthcare workers is primarily from countries in Asia and Africa to Europe, North America, and East Asia, including Japan (Li et al., 2014; Sato, 2009). Under the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) that came into effect in July 2008, nurse and care worker candidates from Indonesia began arriving in Japan in August of that same year.

Under the EPA, foreigners who meet certain application requirements come to Japan as “nurse candidates” or “care worker candidates,” with the aim of obtaining Japanese national qualifications during their respective periods (a maximum of three years for nurse candidates and 4 years for care worker candidates). These candidates receive training at a hospital or caregiving facility in Japan at which they had signed a contract of employment before arriving (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2012).

After obtaining national certification, workers can remain in Japan as nurses or caregivers without restriction. However, if for some reason candidates are unable to obtain national certification within the specified period as a foreign resident, and if specific conditions for extending their period of stay are not met (e.g. if the candidate is unable to receive continued learning support, depending on the year of arrival), these candidates must return to their home countries. These conditions have been strictly enforced (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2013).

Immigrant workers under the EPA (the present study included nurse and care worker candidates, as well as certified workers) work in various environments, jobs, and systems, depending on the facilities they contract with, and may face difficulties and stress working under conditions that are not standardized (Nagae et al., 2013). In addition, living and working in Japan – a country with a culture likely to be very different from their home culture – may be additional sources of stress. Kent (2014) reported that, as a society, Japan remains immature in terms of multicultural coexistence. Because Japan has a strong monocultural society, the multicultural policy in local cities is intended to promote the integration of non-Japanese residents into a local area rather than creating a society amenable to different cultural backgrounds. These daily stresses may have an impact on the mental health of immigrant workers.

Literature review

There are several published studies indicating health issues among migrant workers associated with work conditions in various settings. Janta et al. (2011) addressed the harsh working conditions of the hospitality sector in the United Kingdom (UK), which is accessible to immigrants hoping or needing to enter the labor market at the earliest opportunity. Meyer et al. (2014) identified a number of mental health problems, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, faced by Cambodian immigrant workers in Thailand engaged in sectors such as agriculture, domestic work, manufacturing, and fisheries. Zaller et al. (2014) conducted a cross-sectional survey of immigrant women working in the entertainment sector in China, which identified risky drinking practices in this group.

Regarding immigrant health workers, Bidwell et al. (2014) conducted a semi-structured interview of 16 South African doctors and nurses who had migrated to the UK seeking employment in a first-class care system. However, instead of obtaining new skills, many (particularly nurses) felt that they had become “de-skilled” by restrictions placed on the utilization of their nursing skills. In addition, Baptiste (2015) reported that some internationally educated nurses in the United States (US) experience workplace discrimination, which they perceived as an obstacle to career advancement and professional recognition. Other studies have reported the unfavorable working conditions of immigrant nurses, such as lower salaries compared to local citizens, restriction to less desirable jobs, and down-grading of their position to nurse aides (Kline, 2003; Blake, 2010). While a great deal has been written about the health issues of immigrant workers in other work settings, little is known about the health status of immigrant health workers.

Study purpose

The aim of this study was to assess the mental health status of Indonesian immigrant healthcare workers living and working in Japan under the EPA.

Methods

Design

A descriptive correlational design was employed in this study.

Participants and data collection

Participants were Indonesian EPA immigrant workers who immigrated to Japan, regardless of the year of their arrival. Data collection was performed from November 2012 to March 2013. Survey request forms and anonymous questionnaires were mailed to the managers of facilities that openly announce the employment of Indonesian EPA immigrant workers on their website (206 workers from 87 facilities). These facilities were identified using the key words “EPA,” “Indonesia,” “health professionals,” and “health workers.” The managers distributed the questionnaires to the workers at their respective facilities. Only those workers who consented to participate in the survey completed the questionnaire.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted upon receiving the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of the Senri Kinran University Nursing Department, Japan. The intent of the survey was written on the title page of each questionnaire, and it was clearly stated that cooperation in the survey was voluntary and that anonymity would be preserved.

Study instrument

Demographics

The demographics of the study group were determined from questions addressing population and household conditions, as well as socioeconomic conditions. The population and household condition questions examined, gender, age, marital status, place of birth, religion, number of years living in Japan, Japanese language ability, number of Japanese friends/acquaintances with whom they often had contact, and Indonesian friends/acquaintances with whom they often had contact. The socioeconomic condition questions examined academic background, classification of the present workplace, number of years working at the present workplace, work pattern, target national qualification, status of acquiring this national qualification, and number of years working in the healthcare sector in their home country.

Level of mental health (General Health Questionnaire 28)

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), developed by Goldberg in 1978 and widely used in various research fields, was used to measure the mental health level of the participants (Nakagawa & Daibow, 1985). The GHQ60 (60 items), the shorter GHQ30 (30 items), and the GHQ28 (28 items) are different versions of the GHQ, and Fukunishi (1990) has previously reported the efficacy of these shorter versions. In the present study, the GHQ28 was used, taking into consideration the burden of extensive questioning of the participants.

The GHQ28 has been utilized in various research settings in many countries. Suda et al. (2007) used the GHQ28 for male Japanese factory workers to investigate the association between health practices and mental health status. Choobineh et al. (2013) applied the GHQ28 to assess the psychological health status of dentists in Iran, and Leignel et al. (2014) used the GHQ28 to assess mental health status in self-employed lawyers in France.

The GHQ28 contains 28 items composed of four sub-scales: somatic symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression. Each subscale has seven related questions. Following the guidelines for the Japanese version, four choices for each item were graded as 0-0-1-1 points from the left, and the total score was then determined (Nakagawa & Daibow, 1985). The highest possible score for the GHQ28 is 28, with a higher score indicating a poorer level of mental health. Based on the guidelines, individuals with a total score of five points or less are considered to be healthy, whereas those scoring six points or higher are at risk of mental health problems. Numerous studies have investigated the reliability and validity of the GHQ28 in various clinical populations and reported its usefulness independent of cultural difference, language, and religion (Nakagawa & Daibow, 1985). The Cronbach's alpha (reliability coefficient) for the GHQ28 in the present study was 0.89, suggesting high internal consistency.

The content of the survey was determined with assistance from a university-affiliated Indonesian collaborator who had previously studied in Japan. Given the limited Japanese language ability of the participants, the same collaborator added Indonesian translations below all Japanese question items.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to assess the demographics and mental health status of the participants. We divided the participants into two groups: the “risk absent group” and the “risk present group,” based on the GHQ28 total score. A t-test was performed to compare the values of the total score and of sub-scales. The Fisher's exact test or an unpaired t-test was performed for all survey items to investigate the factors influencing mental health. SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for analyses, and the level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

The questionnaire was distributed to 87 facilities nationwide, from Hokkaido in the north to Kagoshima in the south. Six of the 87 facilities returned 15 questionnaires uncompleted for various reasons, including that the immigrant workers had already returned to Indonesia or had moved to another facility. Responses were obtained from 71 of the 191 questionnaires sent to immigrant workers in 35 facilities (a facility recovery rate of 43.2%, and an actual participation rate of 37.2%).

Demographics

The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

| Items | |

|---|---|

| <Population and household conditions> | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 57 (80.3) |

| Male | 14 (19.7) |

| Age (range: 24-36) | 28.8 (±2.78) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 49 (70.0) |

| Married | 21 (30.0) |

| Place of birth | |

| Java Island | 50 (70.4) |

| Sumatra Island | 14 (19.7) |

| Sulawesi Island | 4 (5.6) |

| Nusa Tenggara Island | 2 (2.8) |

| Other | 1 (1.4) |

| Religion | |

| Islam | 43 (60.6) |

| Hindu | 1 (1.4) |

| Catholic | 8 (11.3) |

| Protestant | 19 (26.8) |

| Number of year living in Japan | |

| Less than 1 year | 3 (4.2) |

| 1 to 2 years | 9 (12.7) |

| 2 to 3 years | 23 (32.4) |

| 3 years or more | 36 (50.7) |

| Level of Japanese language proficiency | |

| Still find daily conversation difficult | 40 (56.3) |

| No problem with daily conversation | 25 (35.2) |

| Able to follow conversation most of the time | 6 (8.5) |

| Number of Japanese friends/acquaintances you often contact | |

| Almost none | 2 (2.8) |

| 1 to 2 persons | 6 (8.5) |

| 3 to 5 persons | 20 (28.2) |

| 5 or more | 43 (60.6) |

| Number of Indonesian friends/acquaintances you often contact | |

| Almost none | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 to 2 persons | 3 (4.2) |

| 3 to 5 persons | 5 (7.0) |

| 5 or more | 63 (88.7) |

| <Socioeconomic conditions> | |

| Academic background† | |

| D3/D4 | 58 (81.7) |

| S1 | 11 (15.5) |

| S2 | 1 (1.4) |

| S3 | 1(1.4) |

| Classification of the present workplace | |

| Hospital | 50 (71.4) |

| Special nursing home for the elderly | 14 (20.0) |

| Long-term care facility | 6 (8.6) |

| Number of years working at the present workplace | 2.25 (±1.2) |

| Work pattern | |

| Part time | 6 (8.7) |

| Full time | 63 (91.3) |

| Target national qualification | |

| Nurse | 49 (73.1) |

| Care worker | 18 (26.9) |

| Status of acquiring the national qualification | |

| Not acquired | 43 (61.4) |

| Acquired | 27 (38.6) |

| Number of years working in health care in the home country‡ | 3.5 (±2.52) |

- † D3/D4: D3 and D4 correspond to graduating from 3 and 4-year vocational schools, respectively (Diploma), S1: bachelor, S2: Master, S3: Doctor.

- ‡ Six people with no experience in nursing are included. Values are N (%) or mean ± standard deviation (SD). The totals for some categories are not equal because of missing data.

Of the 71 participants, 57 (80.3%) were women, with a mean age of 28.8 years, and 70.0% of the participants were single. For the level of education, 81.7% were classified as D3/D4 (which correspond to graduating from 3 and 4-year vocational schools, respectively). Most participants sought the national nursing qualification (73.1%), followed by the national care worker qualification (26.9%). The status of acquisition of the qualification was “not acquired” in 61.4% of participants, and “acquired” in 38.6%.

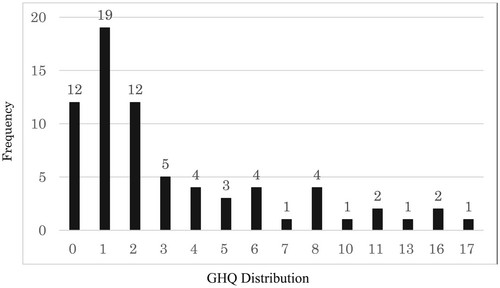

Mental health survey

All survey items in the GHQ28 were graded using the 0-0-1-1 point system; the minimum possible score was 0 points, the maximum was 17 points, and the mean was 3.46 points (standard deviation [SD] = ±4.07). Based on the guidelines, a total score of five points or less represented a healthy individual, while six points or more indicated an individual at risk of having mental health problems (Nakagawa & Daibow, 1985). In this study, 55 (77.5%) participants scored five or less, and the remaining 16 (22.5%) were at a risk of developing a mental health problem (see Fig. 1 for score distribution).

All items were divided into two groups based on the results of the mental health survey. Participants scoring five points or less were the “risk absent group” and those scoring six points or more were the “risk present group.” A t-test was applied to compare the total scores and scores of the four sub-scales. A significant difference was observed in the total score (P = 0.000) as well as all sub-scales (P < 0.01, P < 0.05). The risk present group scored higher in all sub-scales than the risk absent group, specifically, in the “anxiety and insomnia” sub-scale. The alpha values for the GHQ28 in the total and sub-scale scores are shown in Table 2.

| Sub-scales of GHQ28 | Number of Items | Cronbach α | Total (n = 71) | Risk absent group (n = 55) | Risk present group (n = 16) | t-test | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic symptoms | 7 | 0.89 | 1.23 (±1.60) | 0.62 (±0.89) | 3.31 (±1.74) | -5.97 | 0.000** |

| Anxiety and Insomnia | 7 | 0.90 | 1.06 (±1.89) | 0.29 (±0.53) | 3.69 (±2.47) | -5.47 | 0.000** |

| Social Dysfunction | 7 | 0.57 | 0.94 (±1.05) | 0.69 (±0.77) | 1.81 (±1.42) | -3.03 | 0.007** |

| Severe Depression | 7 | 0.86 | 0.24 (±0.76) | 0.02 (±0.13) | 1.00 (±1.37) | -2.87 | 0.012* |

| GHQ28 Total Score | 28 | 0.89 | 3.46 (±4.07) | 1.62 (±1.41) | 9.81 (±3.83) | -8.39 | 0.000** |

- * <0.05;

- ** <0.01. Values in the table are mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Factors influencing the level of mental health

All items in the survey were analyzed using Fisher's exact test or an unpaired t-test. The results showed a significant difference between the risk absent and risk present groups in only two items: “gender” (P = 0.029) and “status of acquisition of a national qualification” (P = 0.017). For gender, the percentage of women (100%) in the risk present group was significantly higher than men (71.9%). Surprisingly, the percentage of participants in the risk present group was significantly higher in those who had acquired a national qualification than in those who had not (see Table 3).

| Total (n = 71) | Risk absent group (n = 55) | Risk present group (n = 16) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <Population and household conditions> | ||||

| Gender | 0.029* | |||

| Female | 57 (80.3) | 41(71.9) | 16 (28.1) | |

| Male | 14 (19.7) | 14 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Age (range: 24-36) | 28.75 ± 2.78 | 28.56 ± 2.75 | 29.38 ± 2.87 | 0.308 |

| Marital Status | 0.053 | |||

| Single | 49 (70.0) | 42 (85.7) | 7 (14.3) | |

| Married | 21 (30.0) | 13(61.9) | 8(38.1) | |

| Place of birth | 0.898 | |||

| Java Island | 50 (70.4) | 37 (74.0) | 14 (26.0) | |

| Sumatra Island | 14 (19.7) | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Sulawesi Island | 4 (5.6) | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Nusa Tenggara Island | 2 (2.8) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Religion | 0.236 | |||

| Islam | 43 (60.6) | 34 (79.1) | 9 (20.9) | |

| Hindu | 1 (1.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Catholic | 8 (11.3) | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | |

| Protestant | 19 (26.8) | 16 (84.2) | 2 (15.8) | |

| Number of years living in Japan | 0.113 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 3 (4.2) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 to 2 years | 9 (12.7) | 9 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2 to 3 years | 23 (32.4) | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | |

| 3 years or more | 36 (50.7) | 24 (66.7) | 12 (33.3) | |

| Level of Japanese language proficiency | 0.623 | |||

| Still find daily conversation difficult | 40 (56.3) | 29 (72.5) | 11 (27.5) | |

| No problem with daily conversation | 25 (35.2) | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Able to follow conversation most of the time | 6 (8.5) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Number of Japanese friends/acquaintances you often contact | 0.944 | |||

| Almost none | 2 (2.8) | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 to 2 persons | 6 (8.5) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | |

| 3 to 5 persons | 20 (28.2) | 16 (80.0) | 4 (20.0) | |

| 5 or more | 43 (60.6) | 32 (74.4) | 11 (25.6) | |

| Number of Indonesian friends/acquaintances you often contact | 0.809 | |||

| Almost none | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 1 to 2 persons | 3 (4.2) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | |

| 3 to 5 persons | 5 (7.0) | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | |

| 5 or more | 63 (88.7) | 49 (77.8) | 14 (22.2) | |

| <Socioeconomic conditions> | ||||

| Academic background | 0.825 | |||

| D3/D4 | 58 (81.7) | 45 (77.6) | 13 (22.4) | |

| S1 | 11 (15.5) | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | |

| S2 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| S3 | 1 (1.4) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Classification of the present workplace | 0.461 | |||

| Hospital | 50 (71.4) | 40 (80.0) | 10 (20.0) | |

| Aged-care nursing home | 14 (20.0) | 9 (64.3) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Long-term health care facility | 6 (8.6) | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | |

| Number of years working at the present workplace | ||||

| 2.25 ± 1.16 | 2.10 ± 1.17 | 2.75 ± 0.99 | 0.058 | |

| Work pattern | 0.604 | |||

| Part time | 6 (8.7) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Full time | 63 (91.3) | 50 (79.4) | 13 (20.6) | |

| Target national qualification | 0.500 | |||

| Nurse | 49 (73.1) | 40 (81.6) | 9 (18.4) | |

| Care worker | 18 (26.9) | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | |

| Status of acquiring the national qualification | 0.017* | |||

| Not acquired | 43 (61.4) | 38 (88.4) | 4 (11.6) | |

| Acquired | 27 (38.6) | 17 (63.0) | 10 (37.0) | |

| Number of years working in health care in the home country‡ | ||||

| 3.55 ± 2.52 | 3.47 ± 2.35 | 3.80 ± 3.15 | 0.661 | |

- * <0.05;

- ** <0.01;

- † D3/D4: D3 and D4 correspond to graduating from 3 and 4-year vocational schools, respectively (Diploma), S1: bachelor, S2: Master, S3: Doctor. Values are N (%) or mean ± standard deviation (SD).

- ‡ Six people with no experience in nursing are included.

Discussion

This study aimed to assess the mental health status of Indonesian immigrant nurses and care workers. Responses from 16 (22.5%) workers suggested that they were at risk of developing mental health problems, and gender and acquisition state of national qualifications were the main factors influencing mental health status.

The GHQ28 was used to investigate the mental health status of the study participants. Mikami et al. (2013) reported that the average GHQ28 score was 13.0 (SD ± 5.88) for 35 newly graduated Japanese nurses three months after they had started working. Gomi et al. (2010) also reported average GHQ28 scores of 11.2 (SD ± 4.6), 10.2 (±4.8), and 7.9 (SD ± 3.7) among 30 newly-graduated Japanese nurses at two, four, and seven months, respectively, after entering the workforce. The average total GHQ28 score was 3.46 (SD ± 4.07), with scores tending to be lower than those of the previously discussed studies.

Comparison of the four GHQ28 sub-scales showed that scores in the anxiety and insomnia sub-scale were the highest in the risk present group, indicating the need for psychological support in the existing support system of the employing facilities.

Approximately 20% of the participants were at risk of developing psychological problems. According to Kessler et al. (2008), more than 25% of Americans were affected by mental disorders (as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV,the standard classification of mental disorders used by mental health professionals in the US) during a survey period from February 2001 to April 2003. Kawakami et al. (2008) stated that 7.0% of Japanese were affected by some form of mental disorder during a survey period between 2002 and 2004, similar to the prevalence in China, but 2-3.5 times lower than in the US. We did not intended to investigate the prevalence, but rather to assess the risk of mental health problems. Although there may be a difference between prevalence and risk rate, we found similarities to the US study, and a considerably higher rate than determined in the Japanese study.

We found that gender and status of acquisition of a national qualification were the most important risk factors for developing psychological problems. Ebata (2002) and Ozeki et al. (2006) reported that the prevalence of mental disorders is higher in female immigrants than in male immigrants; similar results were observed in the present survey, with all participants in the risk present group being female. These results suggest it may be helpful to offer gender-specific support at these facilities.

The status of acquisition of national qualifications was also a factor influencing mental health, suggesting that current training support at recipient facilities was not adequate to meet immigrants’ needs. According to the Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services (2013), training at facilities that accept nurse and care worker candidates is established under certain conditions, with provision of appropriate training incorporating information on preparation for national examinations, as well as training managers and provision of learning support of specialized knowledge and skills. Additionally, assistance with the Japanese language and lifestyle provides opportunities for ongoing study of the language and promotes adaptation to the workplace and lifestyle habits in Japan (Japan International Corporation of Welfare Services, 2013). However, there is no uniform national policy regarding the content of these training programs (Nagae et al., 2013). Instead, each individual facility accepting immigrant workers is entrusted to provide appropriate support. Moreover, the cost of training is the responsibility of the facility; therefore, there is considerable variability in conditions and performance between facilities (Kim, 2010; Nagae et al., 2013).

In the EPA framework, if an immigrant worker succeeds in the national examination, he or she can remain in Japan as a nurse or care worker (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2012). However, in the present study, the status of acquisition of national qualifications was a factor influencing mental health, and the risk of psychological problems was higher in participants who had obtained the relevant national qualification. No continuous and/or comprehensive support services have been established that target immigrant workers who have passed the national examination for the transitional period between working as a candidate and working as a qualified nurse or care worker. Nagae et al. (2013) stated that for nurse candidates, the primary effort at the policy level was directed at helping candidates to pass the national nursing examination; however, there was no mention of support for the candidates who succeed in passing the examination. In fact, Furukawa et al. (2012) reported the importance of establishing a continuous support system and effective means of education, even after passing the examination. The risk of mental health problems among candidates who have passed the examination may be related to the current situation.

It has been seven years since the initiation of acceptance of foreign candidates by the EPA; however, there is little public knowledge of the conditions of specific support provided by the various facilities that accept such candidates in Japan (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2013. According to a report by Tukazaki (2010), the director at one medical facility stated that measures supporting foreign nurses to pass the national examination were a top priority at their facility, and after passing the examination, nurses undergo practical training in all areas of the ward. This approach was originally developed by this particular facility, which has been accepting foreign candidates throughout, and, therefore, has extensive experience in training and developing foreign staff. Other facilities with similar experiences may serve as benchmark facilities. In addition to support provided by the recipient facilities, there are some volunteer groups that provide support to Indonesian immigrant workers, such as telephone counseling in Indonesian, language training, home stay, and social gatherings, aimed at establishing a better living and working environment for both Indonesians and others who work at the recipient facilities (Miyazaki, 2009).

There are useful lessons to be learned from other countries with more experience accommodating foreign health workers. Carbery (2007) stated that assignment of an experienced, fair-minded, nurturing, and dedicated nurse to act as a mentor is important when an overseas nurse joins the staff for clinical direction. It has also been suggested that it may be beneficial to assign a cultural or social mentor to help overseas nurses become established in the community, and to assist them with tasks such as housing issues, obtaining a driver's license, and enrolling children in local schools. Brush (2008) reported several activities for foreign nurses migrating to the US, such as an 18-month internship, an intensive English language instruction course for South Korean nurses in specific hospitals in New York, and a 30-day mandatory orientation in American culture, along with speech therapy to reduce non-English accents among Indian nurses.

Although the requirements for immigrant health workers to start working as a nurse or a care worker are different between Japan and other receiving countries, these experiences may provide helpful suggestions for establishing an effective support system to promote a smooth adjustment for immigrant healthcare workers to a new environment. In addition, sharing the outcomes of successful cases would facilitate the development of a structured program of support for accepted immigrant workers, which is the responsibility of each employing facility in Japan (Furukawa et al., 2012). This would eliminate the current differences in the level of support between facilities. In addition, it would allow for the present support system, which is centered on measures for passing the national examination, to be transformed into one that provides mid and long-term support, after candidates have passed the examination. Additionally, a comprehensive support system, covering not only technical aspects but also psychological aspects, especially at facilities accepting female immigrant workers, is required.

Mandatory attendance at a training program designed for newly employed immigrant nurses may effectively provide gender-specific support. The current program provides technical training as well as mental health support by preceptorships, tutorships, or mentorships throughout the first year of employment; however, the program needs to be made available to foreign staff, particularly female immigrant workers (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2014). Facilities that are unable to establish their own educational program because of financial restrictions may utilize training resources that are available from other facilities in the same region. This may allow Indonesian EPA immigrant healthcare workers to live and work with a healthy mind and body under a continuous support system. Moreover, they may be more likely to remain working in Japan.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. The participants were only recruited from facilities that openly announce the employment of Indonesian health workers on their website. This sampling frame may have caused selection bias that affected the results. There is a constraint of generalizability of these results because of the low recovery rate (facility recovery rate of 43.2%, actual participation rate of 37.2%). Additionally, the survey was conducted in Japanese with supplemental Indonesian translation in order to help the participants understand all questionnaire items. It was not clear to what extent the participants had relied on the translation, and the possible effect on the results of the GHQ28 cannot be excluded, as a full linguistic validation process had not been undertaken. In this study, a quantitative method was used to assess the mental health status of Indonesian workers. To explore this topic further, qualitative methods, such as interviews in Bahasa Indonesia, are needed. There were a couple of participants with a high GHQ28 score; the authors had no process in place to support or make referrals for these specific individuals because of the anonymity of the study design.

Conclusion

Of the 71 immigrant healthcare workers who took part in this survey, 16 (22.5%) were at risk of developing mental health problems. The major factors influencing mental health status were gender and status of acquisition of a national qualification. A continuous and comprehensive support system for Indonesian EPA immigrant workers is necessary.

Implication for nursing practice

It has been seven years since the acceptance of nurses and care workers from overseas under the EPA came into effect; however, sharing of experience among various worksites is minimal. In the future, it is to be expected that more facilities in Japan will accept foreign workers, including those from Indonesia, in the medical and nursing care fields. For such employees to work at similar levels of physical and mental health as their Japanese peers, the experiences gained by the accepting facilities to date should be shared. This may allow the development of a wide support base, while taking into consideration the ability and present situation of immigrant workers at each level of the worksite. In particular, an ongoing support system aimed at workers who have completed the national qualification needs to be established.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the 2011 Scientific Research Fund Subsidy (Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B):Issue No. 23792750).

Contributions

Study Design: FS, KH

Data Collection and Analysis: FS

Manuscript Writing: FS, KH, KK