Humpback whale call repertoire on a northeastern Newfoundland foraging ground

Funding information: Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Grant/Award Number: 2014-06290; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Post Graduate Scholarship; Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada - Ship Time Grants, Grant/Award Numbers: 470195-2015, 486208-2016; University of Manitoba Faculty of Science Fieldwork Support Program Grants

Abstract

Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) are a highly vocal baleen whale species with a diverse acoustic repertoire. “Song” has been well studied, while discrete “calls” have been described in a limited number of regions. We aimed to quantitatively describe calls from coastal Newfoundland, Canada, where foraging humpback whales aggregate during the summer. Recordings were made in July–August 2015 and 2016. Extracted calls were assigned to call types using aural/visual (AV) characteristics, and then agreement between quantitative acoustic parameters and qualitative call assignments was assessed using a supervised random forest (RF) analysis. The RF classified calls well (96% agreement) into three broad classes (high frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), pulsed (P)), but agreement for call types within classes was lower (LF: 63%; P: 85%; HF: 81%). We found support for a repertoire of 13 call types based on either high (≥70%) RF agreement (9 call types) or high (≥70%) AV agreement between two observers (4 call types). Five call types (swops, droplets, teepees, growls and whups) were qualitatively similar to call types from other regions. We propose that the variable classification agreement is reflective of the graded nature of humpback whale calls and present a gradation model to demonstrate the suggested continuum.

1 INTRODUCTION

Describing a species' communication system is a critical first step toward understanding its ecology (Bradbury & Vehrencamp, 1998; Todt & Naguib, 2000). For instance, a well-described acoustic repertoire in some species has elucidated different contingents of a population (e.g., Ford, 1991; Pearl & Fenton, 2008), temporal responses to environmental change (e.g., Luther & Baptista, 2010; Proppe et al., 2012), as well as the mechanisms underlying vocal behavior (e.g., Catchpole, 1982; Payne & Payne, 1985; Waser, 1982). Therefore, before hypotheses can be developed and tested pertaining to call function or variation, it is necessary to describe the number, type, and, in some cases, the discreteness of vocalizations used by a given population and/or species. Repertoire sizes vary within and among species, and many repertoires contain a mix of graded calls (i.e., calls that vary in terms of one or more characteristics creating a continuum of calls with stereotyped cases of each “type” and transitional forms) and discrete calls (i.e., calls with little variation and defined boundaries between call types; Charlton, 2015; Corkeron & Van Parijs, 2001; Ford, 1989; Garcia et al., 2016; Gautier & Gautier, 1977; Marler & Tenaza, 1977). Describing a species' repertoire and capturing the associated variability, both in the call types in a single population and the repertoires among populations, is essential to being able to properly ascribe a sound to the species producing it in the absence of visual confirmation.

Most marine mammals, and likely all cetaceans, rely on sound as their primary communication modality (Dunlop et al., 2007; Tyack, 2000). Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) are a highly vocal cetacean whose acoustic behavior is among the most well studied in the world (e.g., Herman, 2017; Payne & McVay, 1971). Song—a long, stereotyped, and repeated acoustic display thought to function primarily as a reproductive signal—is produced predominantly on breeding grounds and is sung only by males (Cerchio et al., 2001; Cholewiak et al., 2013; Herman, 2017; Payne & McVay, 1971; Stimpert et al., 2012). By contrast, “calls” (also known as “social sounds”; Silber, 1986), “social vocalizations” (Dunlop et al., 2007), “non-song calls” (Dunlop et al., 2008; Fournet et al., 2015; Stimpert et al., 2011) are used across the migratory corridor and in diverse social contexts (Cerchio & Dahlheim, 2001; Dunlop et al., 2008; Fournet et al., 2018a; Stimpert et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 1986), and are produced by males, females and calves (Dunlop et al., 2008; Mobley et al., 1988; Silber, 1986; Winn et al., 1979; Zoidis et al., 2008). Given that some call types are also song units (Dunlop et al., 2007; Rekdahl et al., 2013) and other call types are used independently of social interaction (Fournet et al., 2018a), we adopt the use of the term “call” to refer to any phonation produced by a humpback whale outside of the context of song.

Efforts to quantitatively describe humpback whale call repertoires worldwide are expanding. Humpback whale calls or call repertoires have been quantitatively described on migration routes in Australia (east coast; Dunlop et al., 2007; Harvey Bay, Byron Bay; Rekdahl et al., 2013) and Africa (northern Angola; Rekdahl et al., 2017), along with foraging grounds in southeast Alaska (several locations in SE Alaska; Cerchio & Dahlheim, 2001; Frederick Sound, Alaska; Fournet et al., 2015), and the northern Atlantic (Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, Massachusetts Bay; Stimpert et al., 2011).

Despite marked interest in humpback whale calls over the past decade, there are still many regions where the call repertoire remains undescribed. Approximately 1,000 humpback whales use foraging grounds on the northeast coast of Newfoundland, Canada (Johnson & Davoren, 2021). Humpback whale calling behavior in this region, however, is poorly quantified. There is currently only one qualitative study that describes acoustic communication in this region (Chabot, 1984, 1988). The objective of this study was to characterize and classify the call repertoire of humpback whales foraging off the northeast coast of Newfoundland during the summers of 2015 and 2016. By providing a quantitative description of the call repertoire of humpback whales on a Newfoundland foraging ground, this study will contribute to the growing global catalog of humpback whale calls, and will aid in the identification of calls for potential use in passive acoustic monitoring (PAM).

2 METHODS

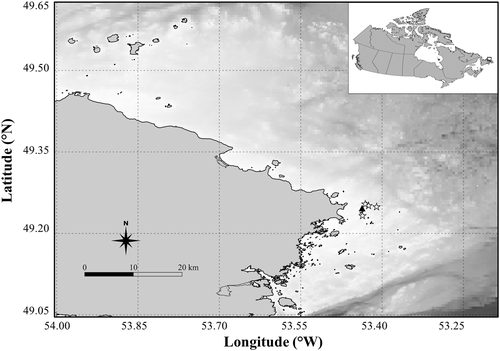

Data were collected on a historic foraging ground on the northeastern coast of Newfoundland, Canada (49.15°N, 53.26°W; Figure 1) using a Wildlife Acoustics SM2M marine recorder (HTI-96 MIN hydrophone, High Tech Inc., Long Beach, MA; recording bandwidth: 2 Hz–48 kHz; sensitivity −165 dB re: 1 V/μPa; flat frequency response from 200 Hz to 10 kHz; Wildlife Acoustics Inc., 2013). Continuous acoustic recordings (24 kHz sampling rate, 12 dB gain, 3 Hz high pass filter, 16 bit) were made during July–August 2015 and 2016. The hydrophone was moored 3 m off the ocean floor, centrally within a cluster of four persistently used shallow-water (15–40 m) spawning sites of a key forage fish species, capelin (Mallotus villosus), where humpback whales are known to forage during the summer (Davoren, 2013). During other shore- and boat-based fieldwork, the timing of arrival of humpback whales within 5 km from the hydrophone was identified (Johnson & Davoren, 2021) and recordings were analyzed for each year starting from the first day of humpback whale arrival until whales were no longer observed and/or calls were no longer found for 48 hours on recordings (July 15–22, 2015; July 29–August 8, 2016).

Selected recordings were reviewed in Raven Pro 1.5 (2015) or 2.0 (2016; hereafter referred to as Raven; Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology; Bioacoustics Research Program, 2014) using a Hann window, 8,192 discrete Fourier transform, 2.93 Hz resolution, and 50% overlap. Recordings with technical malfunctions or excessive noise that might influence parameter measurements were omitted. All nonoverlapping calls with a clearly distinguishable start and end time were annotated in time and frequency by a single observer (M.V.E.).

Acoustic features were extracted using either Raven or the Noise-Resistant Feature Set (NRFS) developed by Mellinger and Bradbury (2007) based on work by Fristrup and Watkins (1993) (Table 1). The NRFS is generally thought to be robust to variable noise conditions and to variation in user annotated selection boxes (Fournet et al., 2015; Fournet et al., 2018b; Mellinger & Bradbury, 2007). For this study, only calls with a signal-to-noise-ratio (SNR) of at least 15 dB above ambient noise were retained for analysis; SNR values were extracted with the NRSF. Initially, 15 variables were measured and included in the classification analyses. A sensitivity analysis was conducted, whereby classification analyses were run with and without certain variables (e.g., start, end, bout), to examine the robustness of the classification success. In the final iteration, the number of inflection points in the peak frequency contour was added to the 15 variables initially measured, which improved classification success (Table 1). All frequency variables were log-transformed prior to analysis, to account for the presumed mammalian perception of pitch (Chabot, 1988; Dunlop et al., 2007; Fournet et al., 2015).

| Variable name | Unit | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower frequency* | Hz | Lower | Lowest frequency of the call |

| Upper frequency* | Hz | Upper | Highest frequency of the call |

| Frequency range* | Hz | Range | Ratio of lower to upper frequency |

| Duration* | s | Dur | Duration of the feature box |

| Bandwidth* | Hz | Band | Height of the feature box |

| Median frequency* | Hz | Median | Frequency at which 50% of the energy is to either side |

| Frequency of peak overall intensity (peak frequency)* | Hz | Peak | Frequency with the greatest energy/amplitude in the feature box |

| Amplitude modulation rate* | Rate | Ampmod | Dominant rate of amplitude modulation |

| Frequency modulation rate* | Rate | Freqmod | Dominant rate of frequency modulation |

| Overall entropy* | Bits | Entropy | Measure of how evenly energy is distributed across the frequencies |

| Upsweep fraction* | % | Upsweep | Fraction of time that the median frequency in one time block is greater than the preceding time block |

| Bout | Bout | Number of the same call type in sequence with relatively equal temporal separation (<2 s) between each instance | |

| Start frequency | Hz | Start | Frequency at the beginning of the call measured on the fundamental frequency or lowest harmonic |

| End frequency | Hz | End | Frequency at the end of the call measured on the fundamental frequency or lowest harmonic |

| Frequency trend | Hz | Trend | Ratio of start to end frequency |

| Number of inflection points in the peak frequency contour | Inflection | Number of times the slope of the peak frequency contour changes |

Calls with a clearly distinguishable start and end and an SNR > 15 dB were aurally and visually (AV) classified by one experienced observer (M.V.E.). A subset of calls (~10%, n = ~104) was reviewed by a second experienced observer (M.E.H.F.) to ensure classification consistency. An observer was considered to be experienced if they had experience classifying humpback whale calls from more than one region for >3 years based on AV characteristics. Aural and visual characteristics were used to place calls into broad classes (Low frequency (LF), Pulsed (P), High Frequency (HF)). Calls within each broad class were then iteratively separated into smaller groups, with randomization of call order between iterations, until the calls within each grouping were subjectively considered to be of a single call type (Fournet et al., 2015). Only call types that were present on two or more nonconsecutive days were included in the final results (Fournet et al., 2015). Resulting call types from this study were then compared to spectrograms, descriptions, acoustic parameters, and/or sound recordings of humpback whale call repertoires available in the literature and supplementary material (Cerchio & Dahlheim, 2001; Darling et al., 2019; Dunlop et al., 2007; D'Vincent et al., 1985; Fournet et al., 2015; Rekdahl et al., 2017; Stimpert et al., 2011; Thompson et al., 1986; Wild & Gabriele, 2014; Zoidis et al., 2008). Through this process, we qualitatively assessed previously described call types for similarity to calls in the Newfoundland recordings. Call types in this study that were qualitatively assessed to be similar to call types previously described were given the same name. All other call types were given new names based on aural and visual characteristics, with careful attention paid not to reuse names of existing call types in the literature.

Following AV classification, classification and regression tree (CART) and random forest (RF) analyses were run with the 16 extracted variables (Table 1) to assess classification to broad classes and to call types. CART and RF analyses have emerged as preferred methods for supervised classification in humpback whale repertoire studies (Fournet et al., 2018b, 2018c; Garland et al., 2012; Rekdahl et al., 2013, 2017). These methods are preferred because they are minimally affected by outliers, nonnormality, nonindependent data, correlated variables, and sample size (Armitage & Ober, 2010; Breiman, 2001; Breiman et al., 1984), all of which are common in humpback whale repertoire studies. The CART and RF were run using the rpart and randomforest packages (R version 3.5.0; Liaw & Wiener, 2002; R Core Team, 2016). The CART and RF were initially run by broad class (LF, P, HF; hereafter “broad class”) and then with all call types together, regardless of call class (hereafter “pooled”), and finally with the call types separated by broad class, where only call types within each class were included (hereafter “within class”; Fournet et al., 2018b, 2018c; Rekdahl et al., 2013, 2017). The Gini index was used in the CART analysis to determine the “goodness of split” at each node (Breiman et al., 1984) and terminal nodes were set to a minimum size of 10 samples. In the RF, the number of predictors considered at each node was set to three, the Gini index was used to assess their importance, and 1000 trees were grown (Fournet et al., 2018b; Garland et al., 2015; Rekdahl et al., 2013, 2017).

A call was considered a discrete call type when agreement between the RF and AV classification was ≥70%. Classification success due to chance was 7% (i.e., based on a 1 in 14 chance of being classified to the original 14 qualitatively identified call types, see below), thus a classification threshold of ≥70% was chosen as a conservative cut-off to indicate high agreement between qualitative categories and quantitative methods as well as between observers. Call types with <70% agreement between the RF and AV classification were reevaluated by a second experienced observer (M.E.H.F.). During reevaluation, the second observer was given a set of unlabeled call clips containing two call types. Each set consisted of a subset of a call type with low agreement (all of calls if n < 25 calls or 20% of the calls if n > 25 calls), along with a similar-sized subset of the call type it was most commonly misclassified as. If AV classification agreement between the two experienced observers was ≥70%, that call type was proposed to be a discrete call type and was included as part of the repertoire, otherwise the call type was not considered a discrete call type and omitted from the final proposed repertoire. A novice observer (G.K.D.) was also given the same subsets, to evaluate whether call types with low quantitative agreement could be distinguished based on AV characteristics with minimal training.

3 RESULTS

In total, 420 hr of recordings over 18 days were reviewed, spanning the two years (2015 = 156 hr over 7 days; 2016 = 264 hr over 11 days). A total of 1,041 calls (2015 = 473 calls, 2016 = 568 calls) were clearly distinguishable and had an SNR >15 dB. These calls were qualitatively divided into three broad classes (LF, P, HF) and 14 call types based on aural/visual (AV) characteristics (Table 2). However, after quantitative analysis and AV classification by a second experienced observer, we only found support for 13 discrete call types (see below for details). Five of these call types were qualitatively assessed to be similar to call types from the literature, based on comparison of average parameter values (Table 3) and published spectrograms. Across all call types, mean start frequency ranged from 70.3 to 622.1 Hz, mean peak frequency ranged from 99.9 to 755.4 Hz, and mean duration ranged from 0.2 to 2.3 s (Table 2). Audio clips and spectrograms of all call types described in this study are available at https://eppm34.wixsite.com/marinebio/newfoundland-humpback-whale-calls

| n (2015/2016) | Bout | Lower | Upper | Peak | Band | Median | Range | Trend | Start | End | Dur | Entropy | Ampmod | Freqmod | Upsweep | Inflection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High frequency | 51/48 | 1.1 (0.0) | 536.8 (14.8) | 1,779.9 (99.1) | 686.4 (24.9) | 1,243.1 (98.9) | 737.9 (29.2) | 0.4 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 596.6 (16.2) | 634.9 (16.6) | 0.3 (0.0) | 39.8 (3.9) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 45.1 (4.0) | 4.6 (0.4) |

| Fluctuating moan | 2/12 | 1.0 (0.0) | 444.7 (44.8) | 2,178.9 (180.0) | 755.4 (94.0) | 1,734.2 (170.3) | 903.6 (95.8) | 0.2 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.1) | 507.7 (38.0) | 607.6 (60.3) | 0.6 (0.1) | 65.3 (11.7) | 1.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 34.5 (7.4) | 10.9 (1.6) |

| Oop | 18/16 | 1.1 (0.1) | 551.1 (27.8) | 984.4 (111.1) | 601.7 (29.8) | 433.3 (102.3) | 623.0 (38.2) | 0.7 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 594.8 (30.5) | 604.4 (27.2) | 0.3 (0.0) | 17.6 (2.0) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 51.8 (7.3) | 3.3 (0.4) |

| Yawp | 31/20 | 1.1 (0.0) | 552.5 (17.2) | 2,200.7 (129.4) | 723.8 (34.4) | 1,648.3 (131.0) | 769.0 (40.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 622.1 (20.6) | 662.7 (20.8) | 0.3 (0.0) | 47.5 (6.0) | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.2) | 43.6 (5.7) | 3.7 (0.3) |

| Low frequency | 179/407 | 1.2 (0.0) | 63.4 (1.8) | 356.6 (9.0) | 128.0 (3.5) | 293.2 (8.7) | 141.9 (3.3) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 93.7 (2.6) | 105.1 (2.6) | 0.8 (0.0) | 15.7 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.0) | 1.8 (0.0) | 47.7 (1.0) | 14.1 (0.4) |

| Doo | 11/4 | 1.1 (0.1) | 183.3 (11.9) | 355.8 (42.2) | 238.1 (12.4) | 172.5 (46.8) | 235.4 (10.5) | 0.6 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 270.9 (18.0) | 208.4 (11.0) | 0.3 (0.0) | 13.0 (1.3) | 1.0 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.4) | 17.2 (9.5) | 4.3 (0.6) |

| *Growla | 47/193 | 1.1 (0.0) | 48.5 (1.4) | 301.3 (12.6) | 104.1 (3.7) | 252.9 (12.6) | 115.9 (3.7) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 70.3 (1.3) | 78.0 (1.4) | 0.7 (0.0) | 13.5 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.0) | 1.9 (0.1) | 46.7 (1.5) | 12.8 (0.4) |

| Growl-moan | 16/4 | 1.0 (0.0) | 101.7 (11.3) | 592.8 (68.2) | 267.6 (25.7) | 491.2 (67.2) | 288.3 (16.8) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.7 (0.1) | 135.7 (12.7) | 194.2 (12.3) | 2.5 (0.3) | 23.5 (2.4) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 52.1 (3.6) | 44.5 (6.4) |

| Low moan | 16/41 | 1.0 (0.0) | 142.7 (6.3) | 576.8 (26.4) | 273.1 (11.6) | 434.1 (27.7) | 283.4 (8.6) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 219.2 (9.2) | 237.5 (9.9) | 1.3 (0.1) | 15.9 (1.1) | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 48.2 (2.9) | 21.2 (1.9) |

| Rumble | 2/10 | 4.8 (0.8) | 80.1 (6.4) | 366.0 (95.2) | 114.3 (5.2) | 285.9 (96.4) | 115.7 (4.5) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.0) | 101.5 (6.0) | 115.6 (6.6) | 0.4 (0.1) | 10.7 (1.2) | 2.3 (0.3) | 2.4 (0.3) | 49.1 (11.3) | 5.5 (1.1) |

| *Whupb | 87/155 | 1.1 (0.0) | 48.1 (1.2) | 339.6 (11.9) | 99.9 (3.2) | 291.5 (11.8) | 117.7 (3.4) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 72.4 (1.4) | 86.5 (1.5) | 0.7 (0.0) | 17.6 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.0) | 1.8 (0.0) | 50.0 (1.6) | 12.2 (0.4) |

| Pulsed | 243/113 | 2.2 (0.1) | 125.6 (3.6) | 695.4 (22.8) | 210.2 (5.9) | 569.8 (22.6) | 240.8 (6.2) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.0) | 149.4 (3.4) | 182.2 (5.2) | 0.3 (0.0) | 33.8 (1.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 83.4 (1.7) | 2.5 (0.1) |

| Honk | 0/23 | 3.2 (0.4) | 123.8 (6.0) | 1,259.5 (186.9) | 170.9 (9.7) | 1,135.7 (185.3) | 257.4 (53.8) | 0.1 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 159.5 (8.4) | 165.2 (8.9) | 0.4 (0.0) | 27.4 (4.8) | 2.3 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.2) | 59.5 (7.6) | 5.2 (0.4) |

| *Swopc | 133/48 | 2.2 (0.2) | 107.5 (2.9) | 655.8 (25.5) | 205.8 (7.8) | 548.3 (25.4) | 236.2 (6.3) | 0.2 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 135.3 (2.9) | 143.3 (3.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 34.9 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 85.5 (2.2) | 1.9 (0.1) |

| *Teepeec | 12/29 | 2.8 (0.4) | 55.4 (4.2) | 467.9 (42.4) | 108.8 (9.5) | 412.4 (42.9) | 134.4 (10.8) | 0.2 (0.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 80.4 (3.8) | 86.2 (5.4) | 0.4 (0.0) | 20.4 (1.9) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.2) | 74.4 (5.4) | 4.7 (0.4) |

| *Dropletc | 94/8 | 1.2 (0.2) | 215.3 (21.9) | 618.0 (75.9) | 268.6 (26.3) | 402.7 (66.7) | 298.9 (33.0) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.9 (0.1) | 235.7 (27.1) | 266.5 (24.3) | 0.2 (0.0) | 23.9 (4.7) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0.0) | 49.0 (16.4) | 1.6 (0.3) |

| Call type | Variable | This study | Dunlop et al. (2007)* | Fournet et al. (2015) | Rekdahl et al. (2017)* | Fournet et al. (2018b) (Atlantic) | Fournet et al. (2018b) (Pacific) | Stimpert et al. (2011)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growl | Peak | 104.1 (57.8) |

73 (36) |

128 (75) |

87.4 (15.1) |

116 (62.6) |

||

| Start | 70.3 (20.3) |

62 (18) |

90 (39) |

|||||

| Dur | 0.7 (0.2) |

2.253 (1.268) |

1 (0.7) |

0.8 (0.24) |

0.7 (0.3) |

1.08 (0.3) |

||

| Whup* | Peak | 99.9 (50.1) |

80 (19) |

132 (81) |

106.13 (38.43) |

94.9 (26.2) |

128 (70.3) |

110 (39) |

| Start | 72.4 (21.9) |

52 (34) |

112 (158) |

88.31 (37.27) |

144 (173) |

|||

| Dur | 0.7 (0.3) |

0.748 (0.196) |

0.7 (0.2) |

0.81 (0.3) |

0.6 (0.18) |

0.7 (0.2) |

||

| Swop | Peak | 205.8 (104.8) |

328 (287) |

159 (54.3) |

214 (85.6) |

|||

| Start | 135.3 (39.0) |

244 (242) |

||||||

| Dur | 0.2 (0) |

0.6 (0.3) |

3.9 (4.2) |

0.3 (0.2) |

||||

| Droplet | Peak | 262.5 (120.3) |

309 (140) |

187 (62.6) |

252 (120) |

|||

| Start | 192.1 (75.7) |

238 (146) |

||||||

| Dur | 0.2 (0) |

0.5 (0.1) |

0.4 (0.2) |

0.3 (0.16) |

||||

| Teepee | Peak | 108.8 (61.1) |

191 (101) |

79.2 (28.8) |

154 (70.3) |

|||

| Start | 80.4 (24.5) |

142 (1) |

||||||

| Dur | 0.4 (0.1) |

0.6 (40.5) |

1.1 (1.77) |

0.4 (0.23) |

Given that the CART and RF produced similar results, we focused on the detailed results of the RF in the text, while detailed CART results are available in supplementary material. The broad class CART and RF had 95% (n = 993/1,041; Table S1) and 96% (n = 1,003/1,041; Table 4) agreement, respectively, with observer classifications. In the RF, duration, number of inflection points, amplitude modulation rate, frequency modulation rate, and start frequency were the most important variables based on the Gini index. The pooled CART and RF both had 70% (n = 728/1,041, n = 730/1,041) agreement (Table S2). In general, the highest misclassification rates within each broad class occurred for call types with low sample sizes (Tables 2 and 4). When misclassified, call types were generally assigned to another call type within their broad class (Table S2), as indicated by the high agreement within the broad class CART (Table S1) and RF (Table 4). Consequently, we presented the RF results for the within class analyses.

| n | High frequency | Low frequency | Pulsed | Agreement (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High frequency | 99 | 92 | 1 | 6 | 93 |

| Low frequency | 586 | 0 | 572 | 14 | 98 |

| Pulsed | 356 | 3 | 14 | 339 | 95 |

3.1 Low frequency

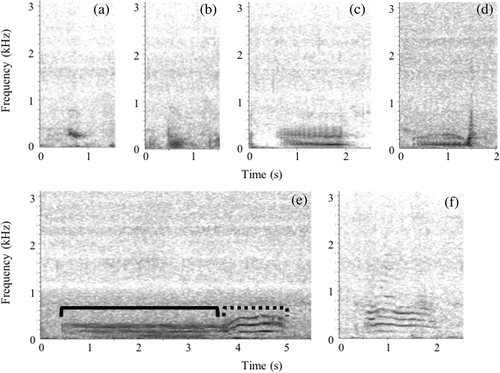

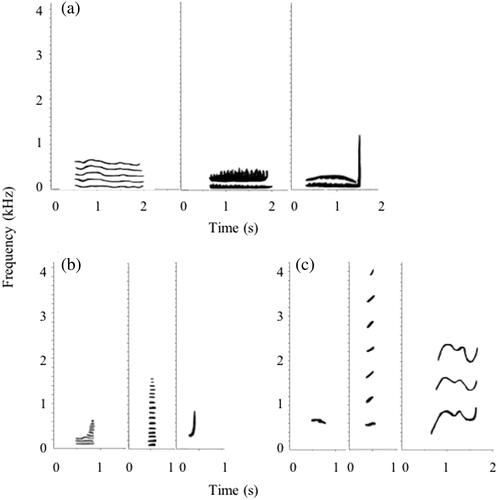

The low frequency (LF) class was the most represented class in the study (n = 586/1,041; Table 2). This within class analysis had 67% (n = 397/589) agreement with AV classification in the CART (Table S3A) and 63% (n = 371/586) in the RF (Table 5A). The most important variables in the RF were end frequency, start frequency, median frequency, overall entropy, and lower frequency. The LF class contained calls characterized by mean peak frequencies ranging from 99.9 to 273.1 Hz, mean start frequencies ranging from 70.3 to 270.9 Hz, and mean durations ranging from 0.3 to 2.5 s (Table 2). Calls in this class were rarely found in bouts (Table 2). This class contained six qualitatively identified call types: doos, growls, growl-moans, rumbles, low moans, and whups (Figure 2). Whups were the most prevalent call type in this class (41%, n = 242) and over all calls (23%), followed closely by growls (41% of LF, n = 240, 23% of all calls; Table 2). Doos and low moans had high classification agreement with AV assignment (>90%), while the other four call types had lower agreement (<70%). Growls and whups were frequently misclassified as one another (Table 5A). Growls and whups had similar mean values for most variables (see Table 2), but differed most in upper frequency, bandwidth, and end frequency, with whups having higher mean values in each of those three variables (Table 2). Growls and whups also each had low variability in most of their average parameters (e.g., peak frequency, median frequency, number of inflection points) relative to the other calls in the LF class, particularly the rumbles, doos, and growl-moans. Similarly, low moans also had lower variability in average values across most parameters (e.g., upper frequency, bandwidth) compared to the growl-moan (Table 2). Growl-moans had very low agreement and were mainly misclassified as low moans (Table 5A). Rumbles also had low agreement and were mainly misclassified as growls (Table 5A).

| (A) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Doo | Growl | Growl-moan | Low moan | Rumble | Whup | Agreement (%) | Agreement between observers (%) | |

| Doo | 15 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 93 | NA |

| Growl* | 240 | 0 | 151 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 85 | 63 | 75 |

| Growl-moan | 20 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 20 | 85 |

| Low moan | 57 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 53 | 0 | 1 | 93 | NA |

| Rumble | 12 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 50 | 92 |

| Whup* | 242 | 0 | 98 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 143 | 59 | 95 |

| (B) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Droplet | Honk | Swop | Teepee | Yip | Agreement (%) | Agreement between observers (%) | |

| Droplet* | 102 | 89 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 87 | NA |

| Honk | 23 | 1 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 74 | NA |

| Swop* | 181 | 8 | 3 | 166 | 4 | 0 | 92 | NA |

| Teepee* | 41 | 1 | 0 | 8 | 32 | 0 | 78 | NA |

| Yip | 9 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 67 |

| (C) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Fluctuating moan | Oop | Yawp | Agreement (%) | |

| Fluctuating moan | 14 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 71 |

| Oop | 34 | 1 | 24 | 9 | 71 |

| Yawp | 51 | 1 | 4 | 46 | 90 |

Due to low agreement (<70%) between RF and AV assignment, three call clip subsets were generated for AV classification by a second experienced observer (M.E.H.F.), including a subset of rumbles and growls, a subset of growl-moans and low moans, and a subset of whups and growls. The two experienced observers had a 92% agreement on the AV classification of rumbles and 85% agreement on the classification of growl-moans (Table 5A). The growl-moan is a compound call containing a growl-like and a moan-like component always heard in the same order, without audible temporal separation between them (Figure 2). The duration of the growl-moan was quite variable across the cases, with much of the variability coming from the duration of the growl portion (Table 2). The two experienced observers had a 75% agreement on the AV classification of growls and 95% on the classification of whups (Table 5A). The novice observer (G.K.D.) reviewed the same subsets. Agreement between the novice and experienced (MVE) was 92% for rumbles, 80% for growl-moans, 87% for growls, and 80% for whups.

3.2 Pulsed

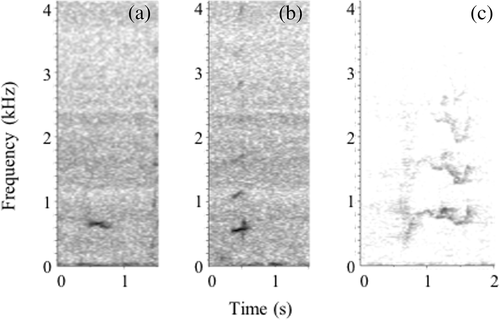

The pulsed (P) class was the second most represented class in the study (n = 356; Table 2). This within class analysis had 85% (n = 301/356) agreement with AV classification in the CART (Table S3B) and 85% (n = 304/356) in the RF (Table 5B). The most important variables in the RF were end frequency, frequency trend, start frequency, lower frequency, and median frequency. The P class contained calls characterized by mean start frequencies ranging from 80.4 to 235.7 Hz, mean peak frequencies ranging from 108.8 to 268.6 Hz, and mean durations ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 s (Table 2). This class contained five qualitatively identified call types: droplets, honks, swops, teepees, and yips (Figure 3). Swops were the most prevalent call type in this class (51% of P, n = 181, 17% of all calls), followed by droplets (27% of P, n = 102, 10% of all calls; Table 2). Calls in this class were sometimes found in bouts, with swops and honks observed in bouts of three or more and droplets often observed in pairs (Table 2).

All calls in this class except yips had relatively high agreement with AV classification (>70% in the RF; Table 5B). Yips were never correctly classified, with the majority being assigned as droplets (Table 5B). Therefore, a call clip subset of yips and droplets was generated for AV classification by a second experienced observer (M.E.H.F.). The two experienced observers had a 67% agreement on the AV classification of yips (Table 5B) and, thus, yips were not included in the final proposed repertoire. The novice observer also agreed with the experienced observer 67% of the time. For the other pulsed call types, most were assigned as swops when misclassified, and a small number of swops were misclassified as all other call types except for yips (Table 5B). Swops had average values for almost all variables (e.g., peak frequency, bandwidth, upsweep fraction) that fell in the middle among the other call types (Table 2). For example, the average peak frequency for swops was higher than honks and teepees, but lower than droplets (Table 2), and average upsweep fraction for swops was higher than teepees and honks, but lower than droplets (Table 2). Swops also had the lowest variability in most average parameter values relative to the other call types in this class (Table 2).

3.3 High frequency

The high frequency (HF) class was the least represented class in the study (n = 99; Table 2). This within class analysis had 85% (n = 84/99) agreement with AV classification in the CART (Table S3C) and 81% (n = 80/99) in the RF (Table 5C). The most important variables in the RF were upper frequency, bandwidth, frequency range, duration, and number of inflection points. The HF class contained calls characterized by mean start frequencies ranging from 507.7 to 622.1 Hz, mean peak frequencies ranging from 601.7 to 755.4 Hz, and mean durations ranging from 0.3 to 0.6 s (Table 2). Calls in this class were rarely observed in bouts (Table 2). This class contained three qualitatively identified call types: fluctuating moans, oops, and yawps (Figure 4). Yawps were the most prevalent call type in this class (52% of HF, n = 51, 5% of all calls; Table 2). All three call types had relatively high agreement with AV assignments (>70%), with some cases of each call being misclassified as each other call type in this class (Table 5C). Some of the averaged variables, including frequency trend, end frequency, and bout, were similar among all three call types, while other variables (e.g., duration, peak frequency, number of inflection points) differed (Table 2). Oops were the shortest duration on average, followed by yawps, then fluctuating moans (Table 2). Similarly, oops had the lowest mean peak frequencies and number of inflection points, followed by yawps, and then fluctuating moans (Table 2).

4 DISCUSSION

This study quantitatively describes the repertoire of humpback whales on their Newfoundland foraging ground. The high agreement of the broad class CART and RF with AV assignment (95%–96%) suggests that calls in the Newfoundland repertoire fit well into the pulsed (P), high frequency (HF) and low frequency (LF) broad classes (Tables 4 and S1). The agreement was lower for call types within each broad class (63%–85%), with only nine of the call types having ≥70% agreement in the RF (Table 5). Review of the other five qualitatively assigned call types with <70% agreement in the RF by a second experienced observer (M.E.H.F.) resulted in high (≥70%) agreement between experienced observers for four of the reviewed call types but not for the other call type (Table 5). Therefore, although we initially characterized 14 call types based on AV characteristics, we only found support for a Newfoundland repertoire of 13 discrete call types.

Five of the call types in the Newfoundland repertoire were qualitatively similar to previously described call types, such that we gave them the same names, i.e., whups (also known as “wops”), growls, swops, droplets, teepees (Dunlop, 2017; Dunlop et al., 2007; Fournet et al., 2015; Rekdahl et al., 2013, 2017; Stimpert et al., 2011; Wild & Gabriele, 2014; Table 3). Also, as noted by previous repertoire studies (Dunlop et al., 2007; Fournet et al., 2015), whups appear similar to moans described by Thompson et al. (1986). Although shared average parameters (i.e., peak frequency, start frequency, duration) of the five calls in the Newfoundland repertoire fall within similar ranges as these call types in other regions (see Table 3) and share similar visual characteristics on spectrograms, we cannot conclusively state that these call types are shared with other regions without direct, quantitative comparisons, as done in previous studies (e.g., Epp et al., 2021; Fournet et al., 2018c). For the same reasons, we cannot conclusively state whether the remaining eight call types described in this study are unique to the Newfoundland foraging grounds, or are simply variants of previously described calls. Growl-moans, however, appear to be a compound call combining growls and low moans and were not found in our survey of the literature. Fortunately, efforts to quantitatively compare call types among regions to build a global repertoire of humpback whale calls have been initiated (Humpback Whale Social Sounds Working Group, initiated in December 2019, at the World Marine Mammal Conference in Barcelona, Spain). To allow these quantitative comparisons, we reiterate recommendations to standardize data collection and analysis methods across humpback whale repertoire studies (Fournet et al., 2015, 2018b; Stimpert et al., 2011). We also reiterate the importance of providing access to sound clips and spectrograms of both stereotyped and transitional examples for graded call types, as well as multiple examples of each call type (discrete or graded) along with publications.

Our findings reinforce the notion brought forward by many previous studies that the humpback whale repertoire contains some discrete calls, as well as many graded calls (Chabot, 1988; Dunlop, 2017; Dunlop et al., 2007; Fournet et al., 2015; Indeck et al., 2020; Rekdahl et al., 2013; Stimpert et al., 2011). This phenomenon has been described in a variety of other species including koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus; Charlton, 2015), Risso's dolphins (Grampus griseus; Corkeron & Van Parijs, 2001), killer whales (Orcinus orca; Ford, 1989), wild boars (Sus scrofa; Garcia et al., 2016), Old World monkeys (superfamily Cercopithecoidea; Gautier & Gautier, 1977), and great apes (family Hominidae; Marler & Tenaza, 1977). This mixed repertoire suggests that some, or all, calls in each of the broad classes may be better classified in a continuum-based manner, rather than into discrete groups, as done, or suggested, for other species (e.g., manatees, Trichechus manatus latirostris; Brady et al., 2020; southern right whales, Eubalaena australis; Clark, 1982).

We attempt here to illustrate how some of the call types within each of the call classes in our study transform into each other (Figure 5), with the caveat that there are likely missing call types and many transitional forms occurring between call types are not illustrated. In the LF class, the low moan appears to grade into the growl with a decrease in bandwidth and a change in harmonic structure (Figure 5A). The growl-moan compound call type may represent a transition between the low moan and growl (Figures 2 and 5). The growl then grades into the whup call by adding an upsweep to the end (Figure 5A). The similarities in growls and whups were evidenced by similar average parameter values (Table 2) and low classification agreement between the RF and AV classification also supported the notion that the transition between these two calls encompasses little change beyond the addition of the upsweep. The whup may also represent a transition between the LF and P classes, as the upsweep portion visually and acoustically resembles a swop or teepee. In support, Fournet et al. (2015) described a call sequence from Alaskan recordings where a single animal moved from a whup into swops and then into teepees. Within the P class, the teepee appears to grade into the swop with an increase in peak frequency and loss of much of the upsweep structure, and the swop then appears to grade into the droplet with an increase in peak frequency and upsweep (Figure 5B). In the P class, many of the average parameter values for swops fell intermediate to honks, teepees, and droplets, with swops having a higher average peak frequency than both honks and teepees, but lower than droplets (Table 2).

Though there were relatively stereotyped examples of each of the call types in the P class, there was variation ranging from these stereotyped cases, including forms that appeared to be transitional between call types. A similar phenomenon of transitional forms was noted in the Alaskan call repertoire, where Fournet et al. (2015) described swops as falling intermediate to teepee and horse calls. Lastly, for high frequency call types, the oop appears to grade into the yawp by increasing in duration and adding a slight upsweep, and then the yawp appears to grade into the fluctuating moan by a further increase in duration and addition of multiple inflections (Figure 5C). This transition between the yawp and the fluctuating moan is another point at which a call type is likely missing in the continuum. Overall, the illustrative continuum presented in Figure 5 is meant to be a representation and starting point for further examination of the continuum.

Variation in the forms within a call type provides support for gradation in the repertoire (Brady et al., 2020) by showing that the boundaries between stereotyped forms of call types are blurred by transitional forms. The presence of transitional forms resulted in difficulties in clearly differentiating the boundaries among the call types (Figures 3 and 5) during AV classification and likely contributed to misclassifications in the CART and RF. Variation within call types, including variation in parameters and transitional forms of call types, may reflect variation related to age, sex, and/or body mass (Charlton, 2015; Gautier & Gautier, 1977). Evidence of such individual-level variation has been found for humpback whale feeding cries (Cerchio & Dahlheim, 2001), as well as cries used in humpback whale song (Hafner et al., 2005). Vocal learning, whereby young individuals produce variations of a discrete call type while they hone their vocal skills (Seyfarth & Cheney, 1986; Tyack, 1997), may be one way calls can vary with age. Indeed, calves of North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) were found to have shorter duration calls, with more nonlinear phenomena, than adult calls (Root-Gutteridge et al., 2018). Given that our recordings likely come from individuals of both sexes and multiple age categories, individual variation could account for variation in call parameters within a call type. Alternatively, variation within call types may follow motivation-structural rules (Dunlop, 2017; Morton, 1977; Smith et al., 1982), evidence for which has been found for humpback whale calls relating to various social behaviors/interactions (e.g., leaving or joining a group) on a migratory route (Dunlop, 2017). Variation related to motivation-structural rules could account for fine-scale parameter differences within a call type and possibly transitional forms. Within-call type gradation does not inherently preclude classifying calls into classes or types (Deecke et al., 2000), but emphasizes the need for further understanding of the drivers of the variability.

Although gradation in the humpback whale call repertoire likely plays a key role in classification success, it also seems that computer-generated or manual measurements of variables did not always capture variation apparent during AV classification (Chmelnitsky & Ferguson, 2012; Janik, 1999). The growls and whups present an example of this (Figures 2 and 5; Fournet et al., 2015; Fournet et al., 2018c), whereby the upsweep was likely not captured by manually extracted or computer-generated measurements. Not capturing the variation, compounded with small sample sizes (Fournet et al., 2015, 2018b; Indeck et al., 2020), likely also contributed to the lower classification success of the rumbles and the growl-moans (Table 5). In all of these cases, experienced observers were able to reliably identify the call types, indicated by high interobserver agreement (Table 5). The novice observer was also able to reliably classify each of these call types, as indicated by the agreement with the AV classification of one experienced observer (M.V.E.). These examples emphasize the importance of using both aural and visual characteristics for call classification; a possible need to adjust quantitative methods or rely on a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods; and/or a need to adjust classification schema altogether.

In conclusion, we have provided the first quantitative description of humpback whale call types on their Newfoundland foraging ground. More years of recordings from this area would help further describe the extent of the repertoire, fill in the gaps in our gradation model, and allow for a thorough examination of transitional forms to help clarify call type boundaries by determining whether they can be defined using limits/rules (e.g., duration, peak frequency). Long-term recordings would also allow us to determine whether some call types found in Newfoundland exhibit stability as observed in other regions (Fournet et al., 2018b; Rekdahl et al., 2013). In the first detailed, quantitative description of the humpback whale repertoire, Dunlop et al. (2007) recommended classification of humpback whale vocalizations into discrete call types, rather than broad classes. Although we found that some call types can be separated into well-defined, discrete types, many are graded and may be better suited to a continuum-based classification (Ford, 1989; Tyack, 1997). We present a gradation model (Figure 5) to provide a broad demonstration of the continuum observed in the Newfoundland repertoire. However, we emphasize that aural and visual classification along with quantitative methods are crucial for understanding the extent of the continuum in terms of the variability within and among call types. Ultimately, determining what level of variation is biologically relevant by linking calls to their behavioral contexts will be key in determining the most meaningful and consistent way to delineate call types or establish call continua (Chmelnitsky & Ferguson, 2012; Dunlop et al., 2007; Fournet et al., 2015; Rekdahl et al., 2013; Silber, 1986; Smith et al., 1982; Tyack, 1997).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Principal funding was provided by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery (2014-06290) and Ship Time Grants (470195-2015, 486208-2016), along with University of Manitoba Faculty of Science Fieldwork Support program grants (2015, 2016) to G.K.D. Additional funding was provided by a NSERC Post Graduate Scholarship (2017–2019) to M.V.E. Thank you to D. Cholewiak and M. Marcoux for feedback throughout the project. We are indebted to the captain and crew of the Lady Easton for their assistance with fieldwork, along with K. Johnson for operating and maintaining the hydrophone in the field, and M. Pitzrick for his support with feature extraction.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mikala Epp: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; validation; visualization; writing - original draft. Michelle Fournet: Methodology; supervision; validation; writing-review & editing. Gail Davoren: Conceptualization; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; supervision; writing-review & editing.