Odevixibat for Episodic Intrahepatic Cholestasis due to Biallelic Mutations in ATP8B1: A Case Series

Funding: The study funder, Albireo Pharma Inc., an Ipsen company, had input during data collection, analysis, and interpretation; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Christine Clemson, Lionel Thevathasan, Velichka Valcheva and Barbara Valzasina: Employee of Albireo Pharma Inc., an Ipsen company, at the time the study was conducted.

Handling Editor: Luca Valenti

ABSTRACT

Background & Aims

In episodic intrahepatic cholestasis (IC; known historically as benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis), intermittent cholestasis is typically followed by periods of remission. During cholestatic episodes, symptoms can include jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and severe pruritus that can interfere with patients' lives. Here, we report clinical features and response to odevixibat, an ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor, in patients with episodic IC associated with biallelic mutations in ATP8B1.

Methods

Clinical information before and after odevixibat initiation was collected.

Results

Six patients diagnosed with episodic IC were included. During cholestatic episodes before odevixibat, all patients had high serum bile acids and severe pruritus associated with sleep and/or mood disturbances that affected patients' quality of life. Physicians initiated odevixibat (dose range: 28–120 μg/kg/day) either during a cholestatic relapse (5/6 patients) or prophylactically (1 patient), resulting in marked symptom improvement in 4/6 (67%) patients and partial improvement in 2/6 (33%); rapid reductions in serum bile acids were reported in 3/6 patients (50%). All patients had improved pruritus and resumed daily activities. Subsequently, patients either stopped treatment after the disappearance of cholestasis or continued treatment. Patients had further cholestatic episodes.

Conclusions

In this case series, most patients with episodic IC associated with biallelic mutations in ATP8B1 treated with odevixibat during a relapse of cholestasis had clinical improvement, including reductions in serum bile acids and positive impacts on pruritus and quality of life. Treatment did not appear to have a preventive effect on future episodes. More studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Summary

- Patients with episodic intrahepatic cholestasis can experience troublesome symptoms, such as extremely itchy skin and yellowing of the skin and eyes, which come and go during their lives.

- When these symptoms occur, it can be hard for patients to sleep, go to work, or enjoy leisure activities.

- In Europe, several patients received a new medication called odevixibat to help treat these symptoms.

- For some patients, this medication made the symptoms less intense during a flare-up, allowing these patients to sleep better or resume activities in their daily lives.

Abbreviations

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- BRIC

-

- benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis

-

- BSEP

-

- bile salt export pump

-

- F

-

- female

-

- FIC1

-

- familial intrahepatic cholestasis 1

-

- IBAT

-

- ileal bile acid transporter

-

- IC

-

- intrahepatic cholestasis

-

- LT

-

- liver transplantation

-

- M

-

- male

-

- MARS

-

- molecular adsorbent recycling system

-

- Mo

-

- months

-

- N

-

- no

-

- N/A

-

- not applicable

-

- NA

-

- data not available

-

- NBD

-

- nasobiliary drainage

-

- PEBD

-

- partial external biliary diversion

-

- PFIC

-

- progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

-

- sBA

-

- serum bile acid

-

- SBD

-

- surgical biliary diversion

-

- TB

-

- total bilirubin

-

- UDCA

-

- ursodeoxycholic acid

-

- US

-

- United States

-

- Wks

-

- weeks

-

- y

-

- year(s)

-

- Y

-

- yes

1 Introduction

Cholestatic liver disease can manifest in a wide spectrum of phenotypes, ranging from episodic disease, including intrahepatic cholestasis (IC) of pregnancy and benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC), to more chronic, progressive diseases, such as progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) [1-4]. Some patients may also evolve through the continuum of cholestatic liver disease, going from an episodic to a progressive phenotype over time [5, 6]. Adding to the complexity, at least 13 genes have been identified as being associated with progressive disease (e.g., ATP8B1, ABCB11, ABCB4, and others that ultimately affect bile flow from the liver) [7, 8], and different genotypic variants also contribute to variability in disease severity (e.g., heterozygous vs. homozygous deficiency in ABCB4 can lead to milder/episodic disease forms [e.g., low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis] vs. more severe disease [e.g., PFIC3 or biliary cirrhosis]) [4, 9]. Furthermore, the nomenclature and classification of episodic phenotypes are unclear. Whereas BRIC, which is associated with variants in ATP8B1 (encoding the familial intrahepatic cholestasis 1 [FIC1] protein) or ABCB11 (encoding the bile salt export pump [BSEP]), has been defined as intermittent attacks of cholestasis that resolve completely without major liver damage [10-12], more recent evidence suggests the phenotype is not always purely benign, with some patients progressing to advanced fibrosis and/or end-stage liver disease [5, 13]. For example, cases of liver transplantation (LT) have been reported in a small number of these patients, including 1 patient with BRIC and ABCB11 deficiency [11], and 1 patient with BRIC and ATP8B1 deficiency [5]. Accordingly, the term episodic IC rather than BRIC may better describe this group of patients.

Patients who exhibit mild cholestatic phenotypes may have variable periods of cholestasis that last for weeks or months, and may be precipitated by various triggers (e.g., infections, stress, medication changes) [14]. During such cholestatic episodes, patients can present with jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, and pruritus that can be so severe as to disrupt patients' daily activities, impact sleep and mental health, and reduce overall quality of life [15-17]. Treatment for this subset of patients with variable cholestatic episodes is primarily aimed at relieving pruritus and shortening the duration of symptomatic periods, and includes off-label medical therapies (e.g., rifampicin and cholestyramine) and invasive procedures (e.g., molecular adsorbent recycling system [MARS], nasobiliary drainage [NBD]) [14-16].

Serum bile acids are typically elevated in patients with cholestasis, including patients with episodic IC, and are thought to reflect the accumulation of bile acids in the liver [18, 19]. Although not completely understood, elevated serum bile acids may contribute to pruritus in patients with cholestasis [17]. The ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT) is involved in the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, resorbing bile acids in the ileum for return to the liver [18]. As such, IBAT inhibitors, which divert bile acids away from the liver to reduce the size of the bile acid pool, have been investigated as treatments for cholestatic liver disease [20]. In clinical trials, the IBAT inhibitor odevixibat produced mean reductions in serum bile acid levels and pruritus in patients with PFIC [21, 22], and odevixibat is now approved for treatment of PFIC in the European Union and for treatment of pruritus in PFIC in the United States (US) [23, 24]. The goal of this case series is to report on odevixibat use in patients with episodic IC who have biallelic mutations in ATP8B1.

2 Methods

Patients were included if they had a diagnosis of episodic IC, defined as: (i) recurrent episodes of cholestasis characterised by high serum bile acid levels, and/or jaundice, and/or pruritus; (ii) spontaneous resolution of signs and symptoms after a few weeks or months; (iii) with or without progression to chronic liver disease [14-17]. All patients had received treatment with odevixibat; treatment decisions, including dose adjustments, were at the discretion of the treating physician. The advised effective dose in PFIC per health regulatory agencies in the US and Europe is 40–120 μg/kg/day, with a daily maximum dose of 6000 μg for US prescribers and 7200 μg for European prescribers [23, 24]. Treatment with odevixibat was maintained for the entire duration of a cholestatic episode; once biochemical parameters returned to within normal values, treatment was ultimately discontinued in 2 patients and continued prophylactically in 4 patients.

Treating physicians from medical institutions in 4 European countries (France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain) collected patient data using standardised case report forms that included fields for patient demographic data, prior medical therapies and/or surgical procedures, and clinical and laboratory information before and after odevixibat initiation. Patients were diagnosed between 1973 and 2013. Data collection for this case series occurred through June 2023 (as available), and all patients initiated odevixibat between February and November 2021. Genetic testing was carried out via Sanger sequencing for all patients except patient 4 for whom additional details are not available. Parameters to evaluate disease progression or hepatocellular damage included biochemical features of cholestasis (e.g., chronic elevation of serum bile acids, total serum bilirubin, and/or liver enzymes), impaired liver synthetic function (e.g., low albumin or prolonged international normalised ratio), and changes in fibrosis (as observed by liver elastography), persistently increased liver stiffness (i.e., following a cholestatic flare), and/or appearance of clinical features of portal hypertension (e.g., splenomegaly, ascites, collaterals, or gastrointestinal varices). During data collection, treating physicians were asked to describe any changes in pruritus or sleep disturbance or impacts the patient noted in his/her daily life during episodes. Adverse events are reported here if supplied by the treating physician but were not queried in the case report forms (as adverse events were to be reported to the appropriate national regulatory body and/or drug manufacturer).

2.1 Case Presentations

Data from 6 patients are included in this case series, with individual patient summaries included below. Demographics and disease course characteristics (including genetic information and extrahepatic symptoms) for all patients are presented in Table 1, and Table 2 provides details on cholestatic episodes before and after odevixibat initiation. Fat-soluble vitamin levels before and after odevixibat was started are shown in Table S1.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP8B1 gene mutationa | c.2932-3C > A; c.2932-3C > A | c.1799G > A; c.1799G > A | c.1982T > C; c.2104G > C | c.3399 + 2G A | c.3069_3070del; c.2771A > G | c.1799G > A; c.1982T > C |

| Predicted mutation pathogenicityb | Pathogenic | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic; not available in database | Not available in database | Pathogenic; uncertain significance | Pathogenic/likely pathogenic (both mutations) |

| Sex | F | M | M | M | M | M |

| Age at onset | 3 months | 3 months | 5 months | 13 years | 17 years | NA |

| Age at diagnosis | 3 months | 7 years | 11 months | 13 years | 19 years | 7 years |

| Age at last data collection, y | 12 | 16 | 18 | 25 | 31 | 56 |

| Extrahepatic symptoms | Hearing impairment | Mild hearing impairment | Diarrhoea, low weight, hearing impairment, asymptomatic gallstones | Tinnitus, diarrhoea | None | None |

- Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; NA, data not available.

- a Mutation information for ATP8B1 included for each patient as available from medical history.

- b Based on ClinVar searches (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) conducted April 1, 2025.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholestasis prior to odevixibat initiation | ||||||

| Total number of historic episodes, y started | 5, 2010 | 2, 2006 | 5, 2006 | 6, 2011a | 15, 2008 | 11, 2016b |

| Frequency of episodes/y, range | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 0–2 | 1–3 |

| Average episode duration, days | 93c | 165c | 66c | 90 | 77c | 39c |

| Reason(s) for starting odevixibat | No response to conventional therapy; to prevent NBD and due to frequency of episodes | To attempt to stop a cholestatic episode | To control pruritus and abnormal liver function | Failure of NBD and plasma-pheresis to treat symptoms | Severe cholestatic jaundice associated with severe pruritus | Recurrent cholestatic episodes with pruritus and fatigue |

| Starting odevixibat dose, μg/kg/day | 90–120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 28 |

| Odevixibat dose change, Y/N, μg/kg/day | Y, 60 | N | N | N | Y, 40 | Y, 36 |

| Type of treatment | During episodes | Continuous | Continuous | Continuous | Initially continuous; then, only during episodes | Continuous |

| Total time on odevixibat, days | 201 | 473 | 774 | 706 | 331 | 657 |

| Reason(s) for stopping odevixibat | Episodes subsided and side effects | N/A | N/A | N/A | Episodes subsided; normal blood tests | N/A |

| Cholestasis after odevixibat initiation | ||||||

| Subsequent number of cholestatic episodes | 2 | 0d | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Time between first odevixibat dose and new episode, days |

1st: 325 2nd: 526 |

N/A |

1st: 271 2nd: 576 3rd: 668 |

1st: 49 2nd: 442 3rd: 616 |

1st: 272 2nd: 493 |

1st: 56 2nd: 406 |

| Average new episode duration, dayse | 56 | N/A | 45 | 38 | 42 | 30 |

- Abbreviations: N, no; N/A, not applicable; NBD, nasobiliary drainage; sBA, serum bile acid; y, year; Y, yes.

- a Episode duration only available since 2015.

- b Episode duration only available since 2020.

- c Average does not include episode that was ongoing at odevixibat initiation.

- d The patient's episode was ongoing from June 2021, prior to odevixibat initiation, and resulted in a liver transplantation in November 2022.

- e Based on available data, does not include episodes that were ongoing at last assessment.

2.1.1 Case 1

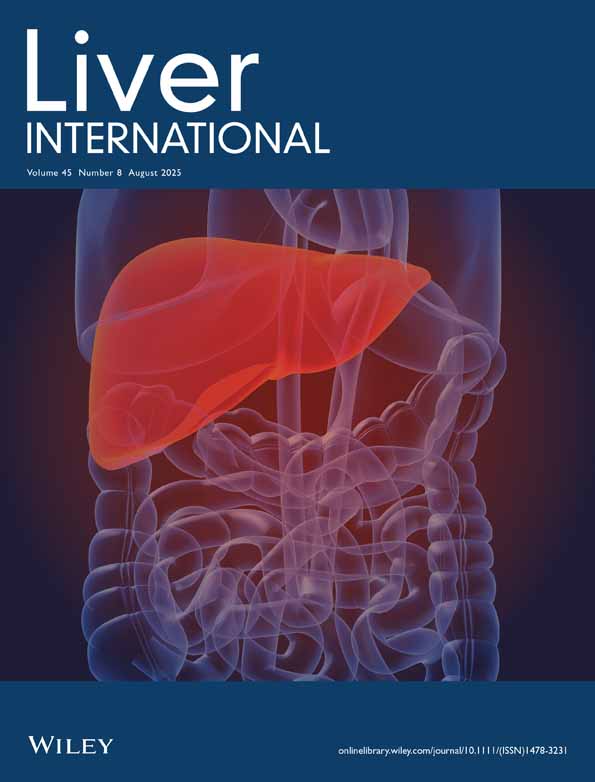

At 3 months of age, a female patient had her first cholestatic episode, which included clinical signs of jaundice, severe pruritus, and elevated serum bile acid and total bilirubin levels (306 μmol/L and 153 μmol/L, respectively). The patient had no family history of cholestatic liver disease; however, her home village was known for a high prevalence of a specific ATP8B1 mutation, and genetic testing confirmed biallelic homozygous mutations in ATP8B1. At approximately 2 years of age, the patient had a second cholestatic episode (severe pruritus and elevated serum bile acids [286 μmol/L]), which was thought to be triggered by the removal of cholestyramine from the patient's treatment regimen (due to constipation). A third episode with a similar clinical profile occurred when the patient was approximately 5 years of age. During this episode, NBD was performed (Figure 1) since standard treatment with cholestyramine, rifampicin, and naltrexone was not effective; this resulted in symptomatic relief for the patient.

The patient then remained asymptomatic for more than 4 years, after which time 3 additional episodes occurred over a period of approximately 2 years; all included symptoms of severe pruritus, moderate sleep disturbances, and elevated serum bile acids (range: 179 to > 180 μmol/L). During these and subsequent episodes, the patient was receiving vitamin supplementation. For the first of these, NBD was employed again, with good effect. Treatment with odevixibat (120 μg/kg/day) was initiated approximately 30 days into the third episode in addition to concomitant rifampicin when the patient was 11 years old. After 3 weeks of odevixibat treatment, the patient's pruritus and sleep disturbances had resolved. At a follow-up visit 35 days into treatment, serum bile acids had normalised (7 μmol/L), and odevixibat was discontinued.

Nine months later, the patient had another cholestatic episode, with moderate sleep disturbances and severe pruritus thought to be triggered by emotional stress (the patient had recently changed schools, started wearing a hearing aid, and had a family member pass away). Odevixibat was reintroduced 7 days after the episode started (90 μg/kg/day), and the patient experienced a marked decrease in pruritus and sleep disturbances within 40 days; clinical and laboratory parameters normalised within 70 days. One month after normalisation of bile acid levels, which fell from 216 μmol/L at odevixibat start to 13 μmol/L, the dose of odevixibat was reduced to 60 μg/kg/day and eventually stopped at the request of the patient due to side effects of diarrhoea and abdominal pain. Three months later, the patient had another cholestatic episode, and odevixibat was reintroduced on the first day that symptoms were reported (reinitiated at her previous dose of 90 μg/kg/day [3 capsules]); after 4 weeks, the dose was increased to 120 μg/kg/day to maximise treatment benefit because her weight had increased since the last episodes; with treatment, a decrease of bile acids (240 μmol/L at start to 39 μmol/L after 4 weeks) and complete resolution of pruritus occurred within 6 weeks. The patient remained on odevixibat for 4 more weeks at a dose of 60 μg/kg/day, after which time it was discontinued due to abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

2.1.2 Case 2

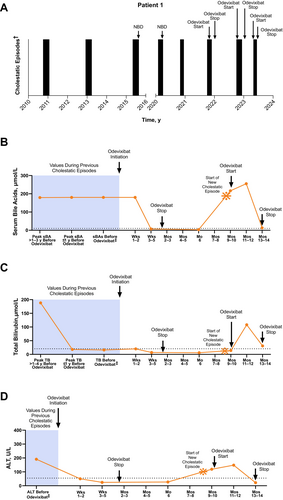

A male patient presented with jaundice and elevated total bilirubin (278 μmol/L) at approximately 3 months of age. Over the next several months, the patient suffered from severe pruritus and elevated total bilirubin levels (73 μmol/L). Due to the severity of his symptoms, the patient underwent partial external biliary diversion (PEBD) at approximately 8 months of age, which resolved the cholestasis (total bilirubin levels 2 months post-PEBD: 6 μmol/L) and pruritus. The patient remained asymptomatic for approximately 5 months, after which time severe pruritus re-emerged. The patient's pruritus gradually improved over the next 6 months. Subsequently, the patient was without symptoms for 13 years. A genetic test conducted when the patient was approximately 7 years of age had revealed biallelic homozygous mutations in ATP8B1.

At 15 years of age, the patient presented with elevated hepatic laboratory values (Figure 2; serum bile acid levels, range: 190–269 μmol/L; total bilirubin levels, range: 269–414 μmol/L) and severe pruritus. This episode was burdensome to the patient, as he experienced tiredness and feelings of shame because of the jaundice, which resulted in frequent skipped school days. When this episode started, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was initiated, followed by rifampicin 1 month later; both were continued for another month together, at which time odevixibat was initiated (with UDCA and rifampicin continued concomitantly). Over 11 months of continuous odevixibat treatment, the patient's serum bile acids gradually decreased but did not normalise (141 μmol/L). Although improvements in pruritus (from severe to moderate), sleep disturbance, and ability to perform school duties were reported during this time, the patient continued to have jaundice and elevated laboratory values (total bilirubin level: 270 μmol/L). Trials of plasmapheresis and glycerol phenylbutyrate had no additional effect. As a result, the patient underwent LT at 16.5 years of age. The surgical biliary diversion that was previously performed was reversed, and odevixibat was restarted approximately 4 days post LT. In follow-up, no steatosis was observed on ultrasound. Since transplantation, the patient is in stable condition without diarrhoea or graft problems.

2.1.3 Case 3

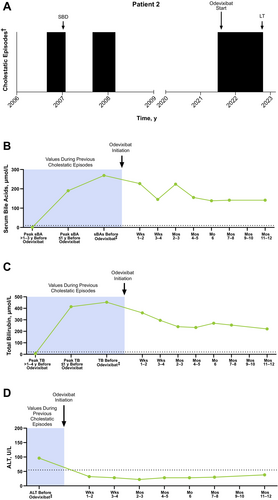

A male patient presented with his first cholestatic episode (severe pruritus, jaundice, discoloured stool, and elevated serum bile acids [251 μmol/L]) within the first year of life. Genetic testing identified compound heterozygous mutations in ATP8B1. In total, the patient experienced 5 episodes in the 15-year period prior to odevixibat initiation. Based on available data, past episodes were generally characterised by severe pruritus and elevated serum bile acids (Figure 3; serum bile acid levels, range: 12–333 μmol/L; median: 258 μmol/L). Some episodes also included symptoms of jaundice, swollen knees, abdominal pain, and/or diarrhoea. During 1 episode, the patient received NBD for 15 days to resolve an episode.

In a subsequent episode, his cholestatic symptoms were so severe that he had to retake his school year. Odevixibat was initiated during this episode (the patient was 15 years and 10 months old at this time); concomitant therapy included UDCA, vitamin supplementation, rifampicin, and glycerol phenylbutyrate. Glycerol phenylbutyrate was given based on the patient's p.I661T FIC1 mutation, which was supported by data from van der Velden et al. 2010 [25]. Approximately 2 weeks after odevixibat initiation, the patient's pruritus resolved and serum bile acids reached near-normal levels (falling from 239 μmol/L prior to odevixibat to 31 μmol/L). However, the patient admitted to poor adherence to treatment, and after 3 months on odevixibat, elevations in serum bile acids and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were observed (163 μmol/L and 153 U/L, respectively) that lasted approximately 3 months (at that time, values were 55 μmol/L and 40 U/L, respectively). The patient had recurrence of moderate pruritus approximately 8 months after starting odevixibat that lasted for 45 days. During the course of odevixibat treatment, the patient was hospitalised several times (during relapses and to improve medication adherence). When the patient reached nearly 18 years of age, he had been consistently taking UDCA and odevixibat for 1 year; however, he had experienced 2 cholestatic recurrences during that time. No adverse events were reported during treatment with odevixibat.

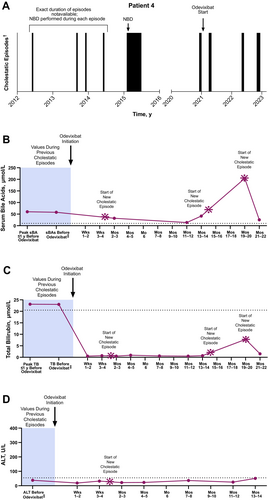

2.1.4 Case 4

Another male patient was diagnosed with episodic IC at 13 years of age (specific genetic details are noted in Table 1). The patient experienced at least 6 episodes in the first 4 years after diagnosis. Based on available data, historical episodes included pruritus; however, laboratory parameters associated with cholestasis were only minimally elevated (e.g., total bilirubin levels ranged from 24 to 30 μmol/L). At 22 years of age, the patient's episodes were almost continuous, and the patient had pruritus and extreme fatigue that impacted his ability to attend school and engage in recreational exercise and sports. Treatments attempted during this and other historical episodes included NBD (Figure 4), MARS, and plasmapheresis; as a result of plasmapheresis performed over years, the patient developed complications of vascular access and secondary hypogammaglobulinemia. The patient subsequently initiated continuous treatment with odevixibat at 23 years of age; concomitant therapies included UDCA, vitamin supplementation, and rifampicin. The patient experienced improved quality of life and the ability to resume work and leisure activities within a few weeks of odevixibat initiation. Approximately 2 months after odevixibat initiation, the patient had a stable clinical status, and an attempt was made to withdraw the concomitant rifampicin. However, withdrawal of rifampicin was rapidly followed by a new episode, during which the patient experienced mild pruritus, asthenia, and insomnia but did not have to stop working. Once rifampicin was restarted, the episode resolved. The patient remained asymptomatic for the following 12 months, followed by 2 additional episodes that occurred 6 months apart. In both cases, the patient experienced mild and/or moderate pruritus and sleep disturbances, asthenia, drowsiness, and temporary leave from work, but each episode was self-limiting and did not require hospitalisation. The most recent episode was thought to be triggered by an upper respiratory infection. At last follow-up, the patient was still taking odevixibat and reported good health and resolution of pruritus.

2.1.5 Case 5

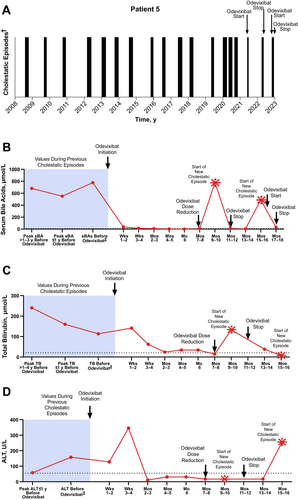

A male patient whose episodic symptoms emerged at 17 years of age had 15 cholestatic episodes in the ensuing years (1–2 episodes per year). These were characterised by severe pruritus and sleep disturbances, as well as elevated levels of serum bile acids and total bilirubin (Figure 5; serum bile acid levels, range: 21–810 μmol/L; median: 551 μmol/L; total bilirubin levels, range: 23–319 μmol/L; median: 162 μmol/L). During a subsequent episode that occurred when the patient was 29 years of age, symptoms prevented him from working and negatively affected his mental health. Odevixibat was initiated at this time. The patient also received concomitant UDCA. Within approximately 6 weeks, the patient's serum bile acids reached near-normal levels (12 μmol/L) and pruritus had completely subsided. The patient had no complaints of pruritus or sleep disturbance for the next 6 months, allowing him to be more confident about the future. At a follow-up visit approximately 7 months after odevixibat initiation, the patient had serum bile acid concentrations < 1 μmol/L but reported diarrhoea and abdominal pain; the dose of odevixibat was subsequently reduced to 40 μg/kg/day. Two months after dose reduction, the patient experienced a new cholestatic episode that lasted 40 days. After this episode subsided, odevixibat treatment was discontinued; beyond this point, the patient received odevixibat only during a cholestatic episode rather than continuously. Six months after odevixibat was discontinued, the patient experienced a recurrence of cholestatic symptoms that included severe pruritus and sleep disturbances and elevated serum bile acid and ALT levels (487 μmol/L and 255 U/L, respectively); these prevented the patient from working during the episode. Odevixibat was reintroduced (120 μg/kg/day), and the episode resolved after 43 days.

2.1.6 Case 6

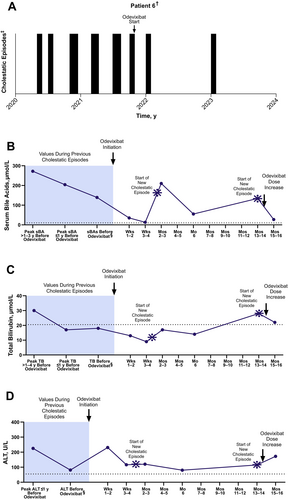

A male patient had experienced intermittent cholestatic symptoms since childhood and received a clinical diagnosis of episodic IC at approximately 7 years of age. Genetic testing performed later confirmed compound heterozygous mutations in ATP8B1. From the available medical history, the patient had been asymptomatic from 44 to 50 years of age; however, between 50 and 53 years of age, the patient had 6 cholestatic episodes. MARS was performed once with little effect. From 53 to 54 years of age, the patient had an additional 6 episodes (each lasting approximately 4–6 weeks). Prominent symptoms during these episodes included elevated serum bile acid levels (Figure 6; range: 85–272 μmol/L), nighttime pruritus, sleep disturbances, prickling sensations in his hands, and fatigue.

The patient initiated odevixibat (28 μg/kg/day) at 54 years of age during a period of fatigue and pruritus; the patient was also receiving vitamin supplementation, cholestyramine, and rifampicin as concomitant medications. After starting odevixibat, concomitant cholestyramine and rifampicin were stopped. In the first month of treatment, the patient had very little pruritus and fatigue and was able to continue working. The patient's serum bile acid and total bilirubin levels during this time were normal or near normal (serum bile acids, range: 13–35 μmol/L; total bilirubin levels, range: 9–13 μmol/L). At approximately 2 months of treatment, a new episode began, coinciding with the administration of a COVID-19 vaccine booster. In this episode, the patient had mild pruritus, which resolved in a month's time. The patient remained mostly asymptomatic for the next 10 months and reported overall good health and quality of life. A new episode occurred shortly before the patient turned 56 years of age that was thought to be triggered by a vitrectomy and cataract extraction. In this episode, the patient had mild pruritus, elevated serum bile acids (134 μmol/L), and sleep disturbances. The resulting fatigue and tiredness ultimately forced him to stop working. The patient's daily dose of odevixibat was increased to 36 μg/kg/day, and serum bile acid levels reached near normal approximately 3 weeks later (27 μmol/L). In the following 6 months, the patient had no episodes with pruritus and could resume his full-time job. Approximately 3 years after odevixibat treatment had been initiated, an attempt was made to stop odevixibat; within 2 weeks, the patient developed pruritus and fatigue. Odevixibat was reinitiated, and the cholestatic symptoms resolved within a few days. The patient remained on odevixibat at the last assessment.

3 Discussion

During cholestatic episodes, patients with episodic IC may have clinical symptoms ranging from biochemical abnormalities to debilitating pruritus [15, 17, 26], and historically, treatment options have been supportive in nature [15]. This case series included 6 patients with episodic IC associated with biallelic mutations in ATP8B1 who collectively had at least 35 cholestatic attacks in the past approximately 15 years. Once odevixibat was initiated, 4 of 6 (67%) patients had marked improvement in symptoms, 2 of 6 (33%) had partial improvement in symptoms, and all patients had improved pruritus for a short period of time, which had positive impacts on the patients' lives.

In terms of laboratory parameters, rapid reductions in serum bile acids were observed in 3 of 6 cases (3, 5, 6, and) within 1–2 weeks of odevixibat initiation relative to the last pre-odevixibat assessment. In general, reductions in serum bile acid levels upon odevixibat treatment were observed within 1–3 months of an episode, regardless of whether odevixibat was administered continuously or only during an episode. Additionally, within a few weeks of odevixibat initiation, all patients had reductions in total bilirubin levels relative to the last value before starting treatment, and most patients had reductions in ALT levels (cases 1–5). Reductions in ALT in some patients were sustained for several months during follow-up. Fat-soluble vitamin levels were generally comparable before and following odevixibat initiation (in patients with available data).

Prior to odevixibat initiation, all patients reported in this case series experienced pruritus during cholestatic episodes. As a result, many patients suffered sleep disturbances, fatigue, and/or tiredness that affected daily activities and reduced quality of life. For example, patients experienced mental health impacts, had reduced school attendance, could not exercise or participate in sports, and/or had problems with work attendance or work performance. After odevixibat initiation, all patients reported improvements in these domains.

Among the 6 patients reported here, 4 used odevixibat continuously, 1 used odevixibat continuously for 10 months before switching to use only during episodes, and 1 used odevixibat solely during episodes. Among these patients, 5 had further episodes. Dosing of odevixibat also varied across patients (ranging from 28 to 120 μg/kg/day); however, these doses are at or under the advised maximum dose of 120 μg/kg/day [23, 24]. The advised effective dose for odevixibat (in PFIC) also includes recommendations for the number of capsules per weight class. Due to changes in patients' weight over time, particularly in children, the dose of odevixibat may change often; furthermore, in older children and adults who may more frequently use 1200-μg capsules, differences in the true dose per kilogram may result. Thus, additional research is needed to determine optimal strategies for treating patients with episodic IC with odevixibat, including understanding ideal doses and durations of treatment.

Cholestatic episode duration before odevixibat in patients 1, 3, 4, 5, and 6 ranged from approximately 30–180 days. With odevixibat, these patients had decreases in hepatic biochemical parameters and resolution of clinical symptoms in 30–70 days. Patient 2 had two prior episodes with durations of 150 and 180 days, respectively; the patient's third episode lasted over a year, during which time odevixibat was started; this patient eventually underwent LT.

Emerging evidence from cases and a natural history cohort suggests that episodic forms of cholestasis due to ATP8B1 deficiency can progress in some patients [5, 13]. Indeed, in this case series, the disease course of patient 2 evolved into a serious, chronic cholestatic state. These data expose certain limitations of the nomenclature historically used to describe episodic forms of cholestasis (i.e., BRIC) since they may not appropriately capture the full phenotypic continuum. Because not all patients with episodic disease have a benign disease course (e.g., certain patients have episodes occur near continuously with no asymptomatic periods or develop advanced liver disease), the authors propose that the term “episodic PFIC1” may more accurately reflect what is encountered in clinical practice.

Two-thirds of all patients in this case series did not require procedural intervention or hospitalisation during an episode after odevixibat was initiated. Exceptions to this included patient 2, who had a PEBD as an infant and whose ongoing cholestasis as a teenager resulted in LT, and patient 3, who was hospitalised during relapses to ensure treatment was administered. This suggests that odevixibat may be an alternative to procedural interventions to abort a cholestatic episode.

There are several limitations of this study. First, in this case series, there were gaps in patients' medical history, and only qualitative descriptions of pruritus symptoms are available (i.e., no formal scale was used). While a specific scale for measuring pruritus was not used in the collection of case data here, a standardised and validated scale for assessing pruritus in patients with PFIC and other paediatric cholestatic liver diseases has been developed and may be useful in future research [27]. Second, all patients in this case series were diagnosed prior to the publication of the 2024 EASL guidelines [28] recommending next-generation sequencing techniques (i.e., whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing) in the diagnostic workup of cholestatic liver disease, and almost all underwent genetic testing via Sanger sequencing. Third, the patients included here had variable dosing and/or duration of exposure to odevixibat, as well as variable concomitant and/or prior medical treatments (e.g., UDCA, rifampicin, surgical biliary diversion). Fourth, the natural history of episodic IC includes self-resolution of cholestasis, making it difficult to determine that the improvements in pruritus and/or laboratory markers of cholestasis observed here were in fact due to treatment with odevixibat. However, given that the timing of improvements occurred shortly after treatment initiation, these data seem to suggest a therapeutic effect of odevixibat. Finally, this study is limited by the small sample size and lack of comparator. Additional investigation into the effects of odevixibat, including factors influencing the variability in response seen across patients and the possibility of a genotype-specific treatment response, would be valuable. That said, the genotype–phenotype relationship in patients with mutations in ATP8B1 is currently unclear, as illustrated by these study data and a study by van Wessel et al., which reported that the number of truncating FIC1 variants (i.e., 0, 1 or 2) was not associated with native liver survival [13]. Furthermore, larger studies of patients with episodic IC who receive odevixibat are needed to elucidate any potential predictors of response, as well as effects in specific subsets of patients (i.e., those with prior surgical biliary diversion).

In conclusion, the patients with episodic IC described in this case series appeared to experience improvements in pruritus, serum bile acid levels, and hepatic laboratory parameters with odevixibat treatment. However, we observed variability in response to treatment and intermittent improvements in parameters in some cases. In addition, no patients discontinued odevixibat treatment during the acute phase, and most continued treatment prophylactically. Overall, a majority of patients did not report side effects. These results suggest that further evaluation of odevixibat in patients with episodic forms of IC is warranted in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Christine Clemson, Velichka Valcheva. Data curation: All authors. Formal analysis: Lionel Thevathasan, Barbara Valzasina. Funding acquisition: Christine Clemson. Investigation: All authors. Methodology: Christine Clemson, Velichka Valcheva. Project administration: Christine Clemson. Resources: Christine Clemson. Software: Lionel Thevathasan, Barbara Valzasina. Supervision: Christine Clemson, Velichka Valcheva. Validation: Lionel Thevathasan, Barbara Valzasina. Visualisation: All authors. Writing – original draft: All authors. Writing – review and editing: All authors.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who contributed to this case series. In addition, we thank Dr. Laure Bridoux-Henno for referring patient 3 and for her help in the care of this patient. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Peloton Advantage LLC, an OPEN Health company, and were funded by Albireo Pharma Inc., an Ipsen company, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines.

Ethics Statement

For patients who participated via an Expanded Access Program, ethics approval was received by a local or central Independent Ethics Committee if required by the physician's respective country.

Consent

Prior to initiating any treatment, treating physicians received informed consent from the patient (or their caregiver). In addition, informed consent was obtained from the patients or their caregivers for publication of the case details presented here.

Conflicts of Interest

A.D.G.: Ipsen and Mirum—Consultant; H.B.: Nothing to disclose; E.G.: Laboratoires C.T.R.S., Mirum, Vivet Therapeutics, and Ipsen—Consultant; M.S.: Ipsen—Consultant; W.L.W.: Mirum—Consultant; C.C., L.T., V.V., and B.V.: Ipsen—Prior employment; H.J.V.: Ipsen, Intercept, Mirum, and Orphalan—Consultant.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

To preserve individuals' privacy, data presented in this manuscript are not publicly available.