HBV: Do I treat my immunotolerant patients?

Abstract

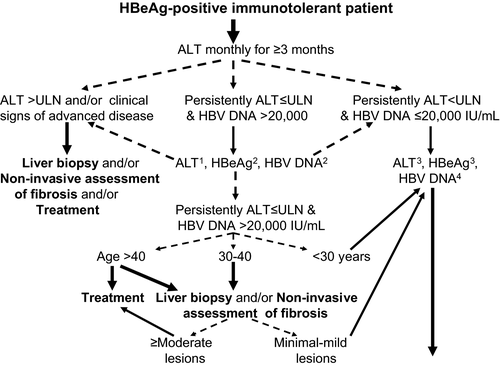

Immunotolerant patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection are characterized by positive HBeAg, high viral replication, persistently normal ALT and no or minimal liver damage. Since the risk of the progression of liver disease and the chance of a sustained response with existing anti-HBV agents are low, current guidelines do not recommend treatment but close monitoring with serial alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and HBV DNA measurements instead. However, not treating all these patients is a concern because advanced histological lesions have been reported in certain cases who are usually older (>30–40 years old), and continued high HBV replication could increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Thus, the optimal management of immunotolerant patients is often individualised according to age, which is associated with histological severity and patient outcome. In particular, immunotolerant patients <30 years old can be monitored for ALT and HBV DNA, while treatment is often recommended in the few patients over 40. A liver biopsy and/or non-invasive assessment of fibrosis may be helpful to determine the therapeutic strategy in patients between 30 and 40 years old. Moreover, there are three specific subgroups of immunotolerant patients who often require treatment with oral anti-HBV agents: patients who will receive immunosuppressive treatment or chemotherapy, women with serum HBV DNA >106–7 IU/ml during the last trimester of pregnancy and certain healthcare professionals with high viraemia levels. More studies are needed to further clarify the natural history for the optimal timing of treatment in this setting.

Abbreviations

-

- ADV

-

- adefovir dipivoxil

-

- ALT

-

- alanine aminotransferase

-

- ETV

-

- entecavir

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- IFNa

-

- interferon-alpha

-

- LAM

-

- lamivudine

-

- NAs

-

- Nuceloside analogues

-

- Peg-IFNa

-

- pegylated IFNa

-

- TBV

-

- telbivudine

-

- TDF

-

- tenofovir disoproxil fumarate

-

- ULN

-

- upper limit of normal

Key points

- Immunotolerant chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) patients have positive HBeAg, high viral replication, persistently normal ALT and no or minimal liver damage.

- Current guidelines do not recommend therapy, but close monitoring with ALT and HBV DNA measurements for most such patients.

- Optimal management of immunotolerant chronic HBV patients is mainly individualised according to age with treatment usually justified in cases over 30 or 40 years.

- Oral antiviral therapy is recommended for immunotolerant patients who receive immunosuppressive/chemotherapy, women with HBV DNA >106–7 IU/ml in the last trimester of pregnancy and certain healthcare professionals with high viraemia.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global public health problem, with an estimated >400 000 000 people with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) worldwide 1, 2. The clinical manifestations of CHB range from acute or fulminant hepatitis to various phases of chronic infection, including inactive carrier state, chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 3. In general, chronic HBV infection is characterized by its dynamic natural course, which includes apparent periodic activation of the host immune system against infected hepatocytes, attempting to eradicate the virus, but usually causing disease exacerbations and leading to progressive fibrosis and ultimately the development of cirrhosis 3, 4. Approximately 15–20% of patients develop cirrhosis within 5 years, whereas 15% of patients with compensated cirrhosis and >60% of those with decompensated cirrhosis die within 5 years 4. Moreover, all patients with chronic HBV infection are at an increased risk of HCC compared to the general population, while the risk increases substantially in patients with prolonged high HBV replication and the presence of cirrhosis 5, 6.

The natural history of chronic HBV infection can be broadly classified into four stages: immune tolerance, immune active/clearance [HBeAg-positive CHB], inactive carrier state and reactivation (HBeAg-negative CHB) 4. Immune tolerance is clinically described as HBeAg positivity with serum HBV DNA levels ≥20 000 IU/ml and no significant immune response to the virus. Thus, these patients have persistently normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels 7. After a period of HBeAg positivity, which varies, immune tolerance to the virus is lost and the immune system attacks the infected hepatocytes. This second immunoactive, HBeAg-positive CHB phase is characterized by fluctuating, but progressively decreasing HBV DNA levels, elevated ALT and hepatic necroinflammation 8. In the third ‘low replication or residual phase’, patients lose HBeAg and develop anti-HBe (HBeAg seroconversion). About 70–80% of them have low viral load (HBV DNA level <2000 IU/ml) as well as remission of hepatitis activity after HBeAg seroconversion and are called ‘inactive carriers’. However, about 20–30% of inactive carriers may enter the ‘reactivation or HBeAg-negative CHB phase’ during follow-up, which is now characterized as a variant of the immune clearance phase 9.

Pathogenesis of the immunotolerant phase

Immunotolerant patients are characterized by high viral replication (serum HBV DNA levels usually >106–7 IU/ml) and low or minimal liver damage 7. Liver biopsies in immunotolerant patients generally show no signs of significant inflammation or fibrosis 10. However, because it is invasive, liver biopsy is not routine in clinical practice in these patients. Thus, serum ALT levels have been used as a surrogate marker of liver cell damage to evaluate the severity of hepatitis activity. Since the natural course of chronic HBV infection is dynamic and even spontaneously reversible, with a severity and duration that varies in each phase, the key to determining true immune tolerance is close, meticulous, long-term follow-up.

Most of the viral populations in immunotolerant patients are wild-type strains whose rate of viral evolution seems to be extremely low. If viral evolution is an interplay between viral replication and host immune selection, the pressure exerted by host immune selection is probably negligible in the immune tolerance phase 11. The mechanism of this tolerance is not yet fully understood. It has been postulated that HBV-specific T-cell hyporesponsiveness may be partly due to ineffective antigen processing and transport to major histocompatibility complex class I molecules 12. Moreover, the innate immune response does not significantly contribute to the pathogenesis of liver injury or to viral clearance, indicating that HBV can spread and remain undetected until an adaptive immune response is mounted 13.

The HBeAg protein has been shown to modulate the innate immune response during the initial phase of infection through interaction with toll-like receptor domains to suppress signaling cascades and down-regulate downstream inflammatory factors such as nuclear factor kappa B 14. This concept is supported by evidence in fulminant hepatitis B, which is closely associated with viral strains carrying the pre-core mutation that cannot produce HBeAg 15. Furthermore, infants born to HBeAg-negative HBV carrier mothers have a high probability of developing acute hepatitis but not chronic infection 16. Thus, HBeAg may serve as an immune tolerogen and facilitate the establishment of chronic HBV infection.

Current treatment indications for chronic HBV patients

There are seven agents that are widely licensed for the treatment of CHB: interferon-alpha (IFNa), pegylated IFNa-2a (Peg-IFNa-2a), lamivudine (LAM), adefovir dipivoxil (ADV), entecavir (ETV), telbivudine (TBV) and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF). These agents can be classified into IFNa's (standard or pegylated), which have both antiviral and immunomodulatory activities and are administered subcutaneously, and the nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs: LAM, ADV, ETV, TBV, TDF), which are pure antivirals and are given orally 2, 17-19. Unfortunately, none of these agents cure most patients with chronic HBV infection. Because anti-HBV treatment can suppress HBV replication and liver disease activity but cannot cure the infection, it is important to treat patients who are at risk of disease progression or who are expected to have a favourable treatment response with a finite duration of therapy. Thus, current treatment indications include patients with elevated ALT, high serum HBV DNA levels (>2000 IU/ml) and at least moderate necroinflammation and/or fibrosis 17-19. Thus, there is no clear treatment indication for HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients with persistently normal ALT, although their high viraemia levels often raise clinical dilemnas and debates about optimal management 7.

Risk of disease progression in immunotolerant patients and possible treatment indications

There have been studies showing that there is no disease progression in HBV immunotolerant patients based on histological findings. In a French study, Andreani et al. 20 retrospectively analysed the results of liver biopsies in 40 adult HBeAg-positive patients with serum HBV DNA levels >10 million copies/ml and normal ALT levels. Histological results evaluated by the METAVIR scoring system showed that fibrosis was absent in 20 and mild (F1) in 20 patients. During a median follow-up of 38 months, loss of tolerance was observed in 12 (30%) patients. Among baseline characteristics, only ALT levels were significantly higher in patients with a subsequent loss of tolerance. In Hong Kong, Hui et al. 21 evaluated liver disease progression in 57 adult patients with high HBV DNA levels, normal ALT (30, range: 4–42 IU/L) on 3 consecutive measurements and baseline liver biopsies showing minimal disease. Patients were followed up every 6 months for 5 years. Nine of the 57 patients (16%) who developed elevated serum ALT levels were discontinued from the study after a follow-up liver biopsy. All 48 patients who remained in the immunotolerant phase for 5 years were biopsied at the end of the study. The follow-up and baseline stage of fibrosis was comparable in 84% of these cases. Progression of liver disease was greater in patients who developed abnormal ALT levels than in those who remained in the immunotolerant phase. These data show that most adult HBV patients in the immunotolerant phase have mild liver disease with no or minimal progression if they remain in the same phase. Therefore, there is no urgent need for treatment in immunotolerant HBV carriers.

However findings have been different in other studies. Lai et al. 22 retrospectively examined 192 patients with CHB: 59 cases with persistently normal ALT (defined as ALT <40 IU/L), 26 cases with ALT levels 1.0–1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) and 107 cases with ALT levels >1.5× ULN. Thirty four per cent of patients with persistently normal ALT had grade 2–4 inflammation and 18% stage 2–4 fibrosis. Unfortunately, ALT follow-up was not strict and misclassification of patients in the ALT groups (in particular overclassification in the persistently normal group) may have occurred. Subgroup analysis showed that most patients with fibrosis belonged to the high-to- normal ALT group. Moreover, older age was significantly associated with advanced histological lesions and only a minority of young, immunotoloerant patients had significant biopsy findings. In another study from India, Kumar et al. 23 prospectively assessed 1387 asymptomatic HBsAg positive patients who underwent liver biopsy and were followed up for more than 1 year. Seventy-three HBeAg-positive patients with persistently normal ALT levels were included. Most of them (60%) had high viraemia levels defined as serum HBV DNA >5 log copies/ml. Histological findings showed that 40% of these patients had significant fibrosis (≥F2, Metavir score). The authors concluded that ALT levels should be considered an imperfect surrogate marker for liver disease activity since it can miss histologically significant disease in a certain percentage patients. The results of the latter study have been criticized for a potential selection bias because the number of patients with persistently normal ALT levels seen during the same period was not reported and the quality of follow-up was suboptimal 24. The presence of significant fibrosis was also strongly associated with older age in that study.

As the association with older age, particularly over 30–40 years old, and significant histological lesions in HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients in several studies 25, 26, current recommendations and many expert opinions suggest that only these older patients (at least >30) should be candidates for liver biopsy to accurately assess the degree of liver injury 7.

Risk of HCC in immunotolerant patients and possible treatment indications

Results have suggested that high HBV replication increases the risk of HCC so that some clinicians support more liberal treatment indications and support treatment in patients with high serum HBV DNA levels, whatever the ALT activity. Since advanced histological lesions and particularly cirrhosis are rarely present in immunotolerant patients, it is possible that HCC does not develop through the pathway of cirrhosis in these patients but through a unique mechanism of hepatocarcinogenesis associated with higher chances of viral DNA integration into chromosomes and inducing genomic instability. Extrapolation of these data supports the need for treatment in all patients with high viraemia levels to reduce the risk of HCC.

This approach is mainly based on the results of the REVEAL-HBV study 27, a large, 11-year, population-based study of 3582 untreated Taiwanese patients with CHB who were followed every 6–12 months with ultrasound examinations and clinical consultations. Results showed that HBV DNA levels ≥106 copies/ml at enrolment were associated with the highest incidence of cirrhosis [relative risk, 9.8; 95% confidence interval (CI), 6.7–14.4; P < 0.001]. The cumulative incidence of cirrhosis was 4.5%, 5.9%, 9.8%, 23.5% and 36.2% in patients with serum HBV DNA levels of <300 copies/ml, between 300 copies/ml and 9.9 × 103 copies/ml, 1.0–9.9 × 104 copies/ml, 1.0–9.9 × 105 copies/ml and ≥106 copies/ml respectively. Further analysis by the same investigators showed a similar relationship between HBV DNA levels and the development of HCC 28.

However, a more thorough review of the REVEAL study cohort reveals that, although many of these patients had normal ALT levels, most of them were HBeAg-negative (85%) and the median age was 45 years old. The natural history of these older patients with longer lasting infection and especially HBeAg-negative CHB is not the same as the natural history of young immunotolerant patients with HBeAg-positive infection, normal ALT and high HBV DNA levels. Therefore, results from the REVEAL study cannot be extrapolated to truly immunotolerant patients.

On the other hand, in a single-centre study of 234 chronic HBV patients who did not meet the indications for treatment at presentation, none of the 44 HBeAg-positive patients developed HCC during a median follow-up of 51 months 29. The authors emphasized that the outcome was favourable in closely monitored patients and in patients who began antiviral treatment when they passed to an active CHB phase. Another large (n = 1553) study from Taiwan in HBeAg-negative patients also does not support initiating treatment for the prevention of HCC alone, because patients with treatment-induced remission had a significantly higher incidence of HCC than patients with spontaneous remission of liver disease activity 30. Thus, extending the treatment indications does not seem to decrease the incidence of HCC and cannot replace close, long-term follow-up in these patients.

Special treatment indications

There are three specific subgroups of HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients who often require treatment. First, HBeAg-positive, like all HBsAg positive patients require prophylaxis with NAs if they are going to receive immunosuppressive treatments or chemotherapy 17. As HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients have HBV DNA >2000 IU/ml, ETV or TDF are the first options for this indication.

Second, HBeAg-positive mothers with normal ALT but high serum HBV DNA levels (>106–7 IU/ml) have >10% risk of vertical HBV transmission to the newborn despite HBV immunoglobulin and vaccination. Therefore, NAs are recommended in this group during the last trimester of pregnancy to achieve low viraemia levels at delivery 17. LAM, TBV and TDF given during the last trimester of pregnancy have been shown to be safe in the mothers and to reduce the risk of intra-uterine and perinatal transmission of HBV in newborns who also receive passive and active immunization 17, 31, 32. If NAs therapy is only given for the prevention of perinatal transmission, it is usually discontinued within 3 months after delivery 17, but close follow-up of mothers should continue because of potential post-partum flares 33.

Finally, HBeAg-positive healthcare professionals with high viraemia levels, especially those who participate in exposure prone procedures, may not be allowed to work in certain countries if they are highly viraemic. Therefore, treatment with NAs may be required to reduce or inhibit HBV replication, even if they have persistently normal ALT 17.

Treatment efficacy in immunotolerant chronic HBV patients

The data on the treatment of immunotolerant patients are limited and usually based on subgroup analyses of HBeAg-positive patients with normal or slightly increased ALT levels at baseline (Table 1). Whether these patients with normal or minimally increased ALT levels fulfilled the criteria of immune tolerance is unclear. Therefore, it is unknown if data from analysis of this subgroup reflect the treatment response of truly immunotolerant patients.

| Study (Ref.) | Patient n | Age, years | Type of study | Agent | Treatment duration | ALT levels | HBV DNA | HBeAg seroconversion (or HBeAg lossa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perrillo et al. 34 | 406 | Median: 34 | Pooled analysis of 4 LAM controlled phase III trials | LAM | 52 weeks |

<ULN: 13.5% 1–2× ULN: 29% 2–5× ULN: 42% >5× ULN: 15.5% |

Median: 98 pg/ml |

<ULN: 2% (1/53) 1–2× ULN: 7% (8/114) 2–5× ULN: 20% (32/164) >5× ULN: 42% (25/60) |

| Chan et al. 35 | 126 | Mean: 33 | Prospective, double-blind, controlled trial | TDF or TDF+FTC | 192 weeks | ALT <43/34 IU/L (males/females) | Mean: 8.4 log IU/ml |

TDF:5% TDF+FTC: 0% |

| Buster et al. 38 | 721 | Mean: 33 | Pooled analysis of two global trials | Peg-IFNa-2a or Peg-IFNa-2b | 48 weeks or 52 weeks | ALT <2xULN | Mean: 9.7 log cp/ml |

Baseline HBV DNA <9 log ≥9 log Gen. A: 46% 28% Gen. B: 21% 21% Gen. C: 25% 29% Gen.D: 11% 7% |

| Liaw et al. 39 | 136 | Mean: 33 | Prospective study of Peg-IFNa-2a in different doses and duration | Peg-IFNa-2a 180 μg/week (subgroup of patients) | 48 weeks |

<2× ULN: 48% 2–5× ULN: 40% >5× ULN: 12% |

Mean: 7.6 log cp/ml |

<2× ULN: 18.5% 2–5× ULN: 44.8% >5× ULN: 61.1% |

- a All response rates refer to HBeAg seroconversion except for this study by Buster et al. 38 which reported rates of HBeAg loss.

- LAM, lamivudine; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; FTC, emtricitabine; Peg-IFNa, pegylated interferon-alfa; ULN, upper limit of normal.

NA(s)

Pooled analysis of four LAM phase III clinical trials including 805 HBeAg-positive patients showed that HBeAg seroconversion was only obtained in 2% (1/53) of patients with normal baseline ALT, compared to 21% of patients with ALT 2–5× ULN, and 47% of patients with ALT >5× ULN after 1 year of LAM therapy 34. A recent study by Chan et al. 35 compared TDF monotherapy and the combination of TDF and emtricitabine in 126 HBeAg-positive NA(s)-naive patients with high HBV DNA levels (mean baseline level of 8.4 log10 IU/ml) and normal ALT, thus, most probably these patients were immunotolerant. After 192 weeks of treatment, the rate of inhibition of HBV replication was higher in the combination than in the monotherapy group (undetectable HBV DNA: 76% vs 55%, P = 0.016) but the HBeAg seroconversion rate was poor in both groups (combination: 0%, monotherapy: 4.7%).

Thus, long-term therapy with NA(s) can achieve inhibition of HBV replication in a proportion of immunotolerant patients, but HBeAg seroconversion rates and the probability of discontinuing therapy are poor (<5%).

(Peg-)IFNa

The probability of response to IFNa or Peg-IFNa therapy in immunotolerant chronic HBV patients has not been studied. The first studies of standard IFNa in HBeAg-positive CHB patients reported that there was a higher probability of HBeAg seroconversion associated with higher aminotransferases and lower HBV DNA levels at baseline as well as with a shorter duration of infection 36. In fact, in the early era of standard IFNa, short courses of prednisone were administered HBeAg-positive CHB patients before IFNa for immunological priming expressed by elevated ALT levels to increase the probability of response to therapy 37. However, this strategy was abandoned in the 1990s because of the risk of severe flares and liver decompensation following prednisolone withdrawal.

In a pooled analysis of 721 HBeAg-positive patients receiving Peg-IFNa based therapy, Buster et al. 38 again showed that a higher baseline ALT level was an independent predictor of a sustained response defined by HBeAg loss and HBV DNA <2000 IU/ml at 6 months post treatment (odds ratio, 1.57 per 1 log10 ULN increase; 95% CI, 1.19–2.09; P = 0.002). Liaw et al. 39 evaluated the treatment efficacy in 544 patients with HBeAg-positive CHB using different doses and durations of Peg-IFNa-2a. The rate of HBeAg seroconversion was 18.5% in patients with baseline ALT between 1–2× ULN and was lower than in patients with baseline ALT 2–5× ULN (44.8%) and 5–10× ULN (66.1%).

According to the above data, we can reasonably assume that Peg-IFNa therapy will offer a low to poor (<15%) probability of HBeAg seroconversion in HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients with no proven benefit over placebo.

Conclusions

Chronic HBV patients in the initial immunotolerant phase have persistently normal ALT, high HBV DNA levels and usually no or minimal histological changes in the liver. Because of the low risk of progression of liver disease and the poor response to the existing anti-HBV agents, current guidelines do not recommend therapy in these patients but close monitoring with serial ALT and HBV DNA measurements every 3–6 months instead 17-19. If treatment with NAs is begun in an immunotolerant patient, reduction or inhibition of HBV replication may be achieved but treatment should be prolonged or indefinite, because the probability of HBeAg seroconversion is extremely low. As immunotolerant patients are usually young, the benefit of inhibiting HBV replication should be weighed against potential adverse events, possible prevention of spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion (10–15% per year in caucasian HBeAg-positive patients) and the cost of long-term NAs.

There has been some concern about not treating all HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients, since advanced histological liver lesions have been reported in some of these patients who are mainly older and continued high HBV replication associated with a prolonged HBeAg-positive phase could increase the risk of HCC and the progression of liver disease 40. Thus, the decisions to perform liver biopsy and to treat HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients should be more effectively individualised especially in relation to patient's age and family history of HCC, two factors associated with the histological severity and patient outcome (Fig. 1). In particular, treatment can be postponed in HBeAg-positive immunotolerant patients who are younger than 30, while it can be recommended in patients over 40. A biopsy is often helpful to make therapeutic decisions in patients between 30 and 40 years old. Treatment should be begun earlier in patients with a family history of HCC 41.

In any case, although the risk of the progression of liver disease is low in immunotolerant patients, it is unpredictable. At the same time, the ability of existing treatments to change the natural history of liver disease and in particular to prevent HCC in these patients is unknown. Therefore, more studies are clearly needed to further clarify the natural history and the optimal timing of treatment in this setting.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: There was no financial support for this manuscript.

Conflict of interest: J. Vlachogiannakos: advisor/lecturer for Abbvie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche. G.V. Papatheodoridis: advisor/lecturer for Abbvie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche; research grants from Abbvie, Bristol- Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Roche; consultant for Roche; Data Safety Management Board for Gilead.