Only partial improvement in health-related quality of life after treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection with direct acting antivirals in a real-world setting—results from the German Hepatitis C-Registry (DHC-R)

Benjamin Maasoumy, Heiner Wedemeyer and Michael R. Kraus contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

Improvement of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is frequently reported as a benefit when treating hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) with direct acting antivirals (DAA). As most of the available data were obtained from clinical trials, limited generalizability to the real-world population might exist. This study aimed to investigate the impact of DAA therapy on changes in HRQoL in a real-world setting. HRQoL of 1180 participants of the German Hepatitis C-Registry was assessed by Short-Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaires. Scores at post-treatment weeks 12–24 (FU12/24) were compared to baseline (BL). Changes of ≥2.5 in mental and physical component summary scores (MCS and PCS) were defined as a minimal clinical important difference (MCID). Potential predictors of HRQoL changes were analysed. Overall, a statistically significant increase in HRQoL after DAA therapy was observed, that was robust among various subgroups. However, roughly half of all patients failed to achieve a clinically important improvement in MCS and PCS. Low MCS (p < .001, OR = 0.925) and PCS (p < .001, OR = 0.899) BL levels were identified as predictors for achieving a clinically important improvement. In contrast, presence of fatigue (p = .023, OR = 1.518), increased GPT levels (p = .005, OR = 0.626) and RBV containing therapy regimens (p = .001, OR = 1.692) were associated with a clinically important decline in HRQoL after DAA therapy. In conclusion, DAA treatment is associated with an overall increase of HRQoL in HCV-infected patients. Nevertheless, roughly half of the patients fail to achieve a clinically important improvement. Especially patients with a low HRQoL seem to benefit most from the modern therapeutic options.

Abbreviations

-

- BL

-

- baseline

-

- BMI

-

- body mass index

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- CLDQ

-

- Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire

-

- DAA

-

- direct acting antivirals

-

- DCV

-

- daclatasvir

-

- DSV

-

- dasabuvir

-

- EBR

-

- elbasvir

-

- EOT

-

- end of treatment

-

- FU24

-

- follow-up 24 weeks after end of treatment

-

- GPT

-

- glutamic-pyruvate transaminase

-

- GZR

-

- grazoprevir

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

-

- HCV

-

- hepatitis C virus

-

- HIV

-

- human immunodeficiency virus

-

- HRQoL

-

- health-related quality of life

-

- ITT

-

- intention-to-treat

-

- LDV

-

- ledipasvir

-

- MCID

-

- minimal clinical important difference

-

- MCS

-

- mental component summary score

-

- MELD

-

- model of end-stage liver disease

-

- OBV

-

- ombitasvir

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- OST

-

- opioid substitution therapy

-

- PCS

-

- physical component summary score

-

- PTV

-

- paritaprevir

-

- RBV

-

- ribavirin

-

- r

-

- ritonavir

-

- SF-36

-

- short form 36 questionnaire

-

- SMV

-

- simeprevir

-

- SOF

-

- sofosbuvir

-

- SVR

-

- sustained virological response

-

- QoL

-

- quality of life

Statement of Significance

Treatment of chronic hepatitis C with modern direct acting antivirals (DAA) is associated with an overall increase of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in clinical trials. Our data estimate the effect on HRQoL after DAA therapy in a large real-world cohort (N = 1180), comprising different population subgroups with a higher hepatitis C virus infection (HCV) prevalence compared to the general population. Importantly, in our study, roughly half of the patients failed to achieve a clinically important improvement in HRQoL. Various risk factors for an absent improvement in HRQoL were evaluated.

1 INTRODUCTION

With an approximate prevalence of 1% (71 million people) worldwide, chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection represents one of the major global health issues.1 HCV is commonly known as a hepatotropic virus. Liver-associated complications of HCV infection comprise the development of cirrhosis in up to 30% of cases, with an annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) of 2%–4%.2 However, in up to 75% of patients, extrahepatic manifestations are present,3 for example lymphoproliferative disorders, type II diabetes mellitus or dermatological diseases.4 Importantly, up to 50% of HCV-infected patients develop neuropsychiatric symptoms such as fatigue, depression or cognitive disorders, which occur independently of the severity of liver disease and may even represent the clinically predominant problem.4, 5

To evaluate the comprehensive consequences of chronic HCV infection, assessment of patient-reported outcomes (PRO), for example the self-reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL), has become of increasing importance. Not surprisingly, an impairment of HRQoL is commonly reported in patients with chronic HCV infection.6-8 Concerns about transmitting the infection to contact persons may deteriorate physical and mental well-being. Also, the medical condition of the liver disease (eg chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis) as well as virus-induced neuropsychiatric extrahepatic manifestations are supposed to contribute to reduced HRQoL.9, 10

Antiviral treatment of chronic HCV infection was revolutionized in 2011 with the approval of the first direct acting antivirals (DAA). Modern DAA regimens are endowed with SVR rates >95% and very moderate side effects.11 Achievement of SVR is associated with normalization of liver enzymes, regression of fibrosis and reduced risk for HCC and all-cause mortality.12 Next to liver-related benefits,13 SVR is regularly reported to be linked to an overall improvement of PRO’s, including HRQoL14 as well as extrahepatic complications including neuropsychological symptoms.15 In some patients with moderate liver disease but a high prevalence of neuropsychological symptoms and/or a low HRQoL (eg drug/alcohol users and/or patients suffering from depression), this may represent the leading motivation to start antiviral treatment.

However, most of the recently available data investigating alterations in self-reported HRQoL under modern DAA combinations were obtained from clinical trials and might have limited generalizability compared to the real-world populations. Especially, population subgroups with a known higher HCV prevalence compared to the general population (eg active substance users16), are regularly excluded from clinical trials.17 Thereby, in patients with active drug usage, HIV coinfection, opioid substitution therapy (OST) or significant alcohol consumption, an impaired HRQoL is commonly reported independently of concomitant HCV infection and therefore, effects of HCV treatment on HRQoL might be partially masked.14, 18, 19

This study aimed to investigate the association of DAA therapy on the likelihood for clinically important improvements of HRQoL in a real-world setting. A particular focus of the analysis was put on subgroups of patients for whom a change in HRQoL was considered to be of particular relevance. Therefore, we longitudinally assessed Short-Form 36 (SF-36) scores before and after DAA treatment within the German Hepatitis C-Registry. Baseline (BL) factors associated with clinically important changes in HRQoL after HCV treatment were sought to be identified.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design and study population

For this real-world study, data were obtained from the German Hepatitis C-Registry (DHC-R), a national real-world cohort of approximately 17,600 HCV-infected patients to date. Registry eligibility criteria include age ≥18 years and written informed consent to study participation and data usage. Collected data include BL sociodemographic information comprising age, sex and ethnicity. Various laboratory variables were obtained at BL, including HC viral load (IU/ml) and HCV genotype.

Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was accepted as confirmed by histology, ultrasound, fibroscan®20 >12.5 kPa or clinical presence of cirrhosis, for example ascites. In presence of cirrhosis, Child-Pugh Score21 and Model for end-stage liver diseases22 (MELD Score) were assessed. Further obtained clinical variables included DAA regimen, comorbidities and actual drug-taking activities or opioid substitution (OST).

All included patients were treated with an all-oral DAA regimen. SVR was defined as undetectable viral load in quantitative PCR or viral load ≤25 IU/ml 12–24 weeks (FU12/24) after end of treatment (EoT).

For the presented analysis, only patients with available HRQoL assessment via the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) at BL as well as FU12/24 were included.

2.2 HRQoL instrument

The SF-36 health survey is an extensively used generic self-administered questionnaire for the assessment of HRQoL, excluding bias by interpretation of health care professionals. The 36 items cover eight domains linked to physical and mental components of QoL. Subscales group questions estimating eight domains (physical functioning [PF]), role physical [RP], bodily pain [BP]), self-perceived general health [GH], vitality [V], social functioning [SF] and emotional role functioning [RE]). The subscales of physical QoL components can be combined to the physical component summary (PCS), equivalent subscales of mental QoL components can be summarized to the mental component summary (MCS), with the subscales GH, V and SF influencing both summary scores. Evaluation was performed according to the recommended protocol.23

2.3 Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the software package SPSS statistics v.26.0 (IBM Corp.24). Data of patients starting antiviral treatment with DAA on or after 1 February 2014 were included in the analyses. These were performed using follow-up data obtained until 9 February 2018. In the statistical process, only data of the intention-to-treat (ITT) population with complete data sets were included (SF-36 data at time points BL, EoT and FU12/24).

Descriptive analyses were performed for various subgroups (eg HIV coinfected patient, age categorized in years <65 vs. ≥65, patients with significant alcohol consumption [defined as consumption of >40 g/days for men and >30/days for women]). As described by Coteur et al.25 and Strand et al.,26 changes in of ≥2.5 points in MCS and PCS of the SF-36 form were defined as the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Therefore, described descriptive analyses were performed in a corresponding way, regarding changes in of ≥2.5 points in MCS and PCS of the SF-36 form.

Longitudinal assessments were realized by the use of paired t tests. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed in order to identify potential predictors associated with changes in HRQoL.23 Logistic regression models were adjusted for sex, age group <65 vs. ≥65 years, GPT BL level norm vs. >ULN, neuropsychiatric comorbidities (depression and fatigue), drug consumption status, alcohol consumption, presence of cirrhosis, ribavirin (RBV) co-treatment, pre-treatment status and BL SF-36 BL scores. The definition of fatigue was based on values below claimed cut-offs in a minimum of two of the SF-36 subscales vitality (value ≤ 35), social functioning (value ≤ 62.5), role physical (value ≤ 50) as proposed by Jason et al., 2011.27 Logistic regression analyses were performed using common criteria in clinical trials (confidence interval [CI]: 95%; statistical level of significance: 5%.)

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of study population

A total of 1180 patients with obtained SF-36 data on BL, EoT and FU12/24 were considered for the analyses. Genotype 1 was the most prevalent genotype in our cohort (81.5%; n = 962/1180). The overall SVR rate (SVR12/24, ITT) was 97.7% (n = 1153/1180). Only 0.3% of patients discontinued DAA treatment. Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

| Parameter | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Patient number | 1.180 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 684 (58.0) |

| Female | 496 (42.0) |

| Age, years | 53.4 (18–84)a |

| Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 1141 (96.7) |

| African | 19 (1.6) |

| Asian | 15 (1.3) |

| HCV related parameters | |

| Used DAA regimen | |

| RBV containing regimens | 299 (25.4) |

| SOF+RBV | 60 (5.1) |

| SMV+SOF±RBV | 30 (2.5) |

| DCV+SOF±RBV | 113 (9.6) |

| LDV/SOF±RBV | 666 (56.5) |

| OBV/PTV/r/RBV | 31(2.6) |

| OBV/PTV/r/DSV±RBV | 206 (17.5) |

| EBR/GZR±RBV | 74 (6.2) |

| Previous HCV treatment | 608 (51.5) |

| Interferon-based | 301 (49.5) |

| All-oral DAA regimen | 117 (19.2) |

| Cirrhosis | 262 (22.2) |

| Decompensated (CPS ≥ B) | 18 (6.9) |

| MELD | 8.5 (6–17)a |

| HCC | 12 (1.0) |

| Comorbidities | 951 (80.6) |

| Active injecting drug users | 236 (20.0) |

| Opioid substitution | 102 (8.6) |

| HIV coinfection | 159 (13.5) |

| Psychiatric disorder | 260 (22.0) |

| Depression | 239 (20.3) |

| Psychosis | 31 (2.6) |

| Attempted suicide | 2 (0.2) |

| Neurological disorder | 36 (3.1) |

| Insomnia | 48 (4.1) |

| Fatigue | 283 (24.0) |

| Alcoholism | 22 (1.9) |

| Autoimmune diseases | 1 (0.1) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 339 (28.7) |

| Tumour diseases | 52 (4.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 129 (10.9) |

| Chronic respiratory diseases | 64 (5.4) |

| Renal impairment | 27 (2.3) |

| Thyroidal dysfunction | 118 (10.0) |

| Skin disease | 24 (2.0) |

| Bleeding disorder | 4 (0.3) |

| Other | 482 (40.8) |

| No comorbidity | 229 (19.4) |

- Abbreviations: DCV, Daclatasvir; DSV, Dasabuvir; EBR, Elbasvir; GZR, Grazoprevir; LDV, Ledipasvir; OBV, Ombitasvir; PTV, Paritaprevir; r, Ritonavir; SMV, Simeprevir; SOF, Sofosbuvir.

- a Mean value (minimum – maximum).

3.2 Changes in the values of HRQoL from baseline to FU12/24

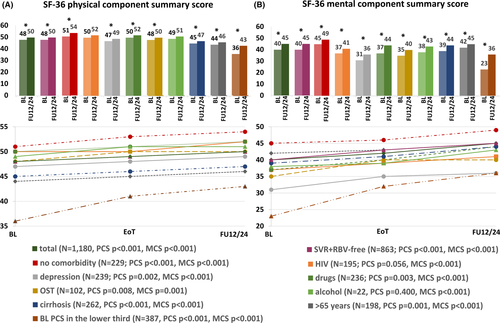

Nine subgroups of patients were considered to be of particular interest when analysing changes in the HRQoL. These predefined subgroups were patients treated without RBV and achievement of SVR (I), as this is the most frequent group when using modern DAA regimens according to the current treatment guidelines,28 those without any comorbidity, for whom we estimated a particularly low risk for an impaired HRQoL (II), those with HIV coinfection (III), depression (IV), active drug usage (V), patients undergoing OST (VI), with significant alcohol consumption (VII) and those with liver cirrhosis (VIII), which were all thought to be at a relevant risk for an impairment of MCS (±PCS)14, 18, 19, 29, 30 and those older than 65 years (IX)31 likely to have an impairment of PCS. BL mean values of subscales and component scores of defined subgroups are shown in Table S1. Analyses of the total study cohort result in a significant improvement of HRQoL from BL to FU12/24 as indicated by a significant increase in the mean values of PCS (48–50; p < .001) and MCS (40–45; p < .001). Moreover, the significant increase in both summary scores was consistently documented over all eight selected subpopulations, with an exception in PCS increase with regard to HIV-infected patients (p = .056) and patients with significant alcohol intake (p = .400). However, although statistically significant, absolute increase of PCS and MCS was rather low for some subpopulations. Among patients ≥65 years absolute mean improvement in MCS and PCS was only 3 (p < .001) and 2 (p = .001), respectively. Similarly, only very moderate but statistically significant changes were documented with regard to physical health in patients with active drug usage (p = .003), opioid substitution (p = .008) and patients with cirrhosis (p < .001). Mean PCS improvement from BL to FU12/24 was only 2 in all three groups. Of note, MCS increase was particularly high in those with active drug use (37–44; p < .001). Considerable improvements of MCS were also documented in patients with alcohol consumption (38–43; p < .001), OST (35–40; p = .001) and liver cirrhosis (39–44; p < .001). However, the highest increase of mental and physical reported health was seen in patients with BL values of PCS and MCS in the lower third of the overall cohort. Mean value of MCS in this subgroup (n = 379) increased from 23 to 36 (p < .001), while PCS (n = 387) increased from 36 to 43 (p < .001) (Figure 1A,B).

3.3 Proportion of patients with statistically significant and clinically important changes in HRQoL

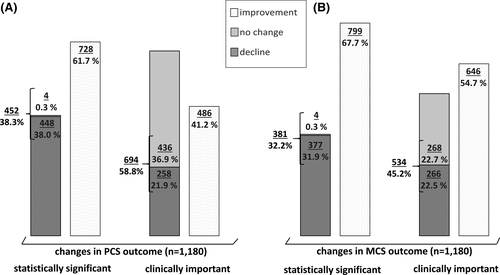

A statistically significant improvement of MCS and PCS values at FU12/24 was reported in 67.7% (n = 799/11,180) and 61.7% (n = 728/11,180) of the overall cohort, respectively. A significant worsening was reported by 31.9% (n = 377/11,180) and 38.0% (n = 448/11,180) in MCS and PCS, respectively.

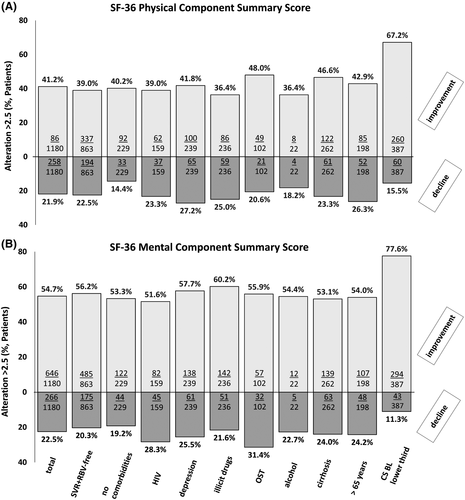

However, taking the defined MCID of ≥2.5 points into account, a clinically important improvement in MCS and PCS after DAA therapy was reported by 54.7% (n = 646/11,180) of the patients, while 41.2% (n = 486/11,180) reported a clinically relevant improvement of PCS. In contrast, a clinically relevant decline of MCS and PCS was reported by 22.5% (n = 266/11,180) and 21.9% (n = 258/11,180) of patients, respectively (Figure 2). We next analysed the proportion of clinically important changes of PCS and MCS in the selected subgroups that were considered to be of particular interest (see above). Overall, there was a similar pattern compared to the total cohort. Clinically important improvements in MCS were more frequently reported in all considered subgroups than improvement of PCS. A high likelihood for a clinically important change in PCS and MCS was present in the group of patients without any comorbidity. Particularly low chances (36.4%) for a clinically meaningful improvement of PCS were documented in patients taking illicit drugs or relevant amounts of alcohol. Remarkably, patients with low MCS and PCS BL values within the lower third of the overall cohort most frequently reported a clinically important improvement at FU12/24 (62.7% for PCS, 77.6% for MCS; Figure 3A,B).

3.4 Baseline parameters associated with clinically important changes in HRQoL

We next aimed to identify predictive factors associated with clinically important changes in HRQoL after DAA therapy. In multivariate logistic regression analyses of the entire study cohort, factors that were significantly associated with clinically important improvement of PCS and MCS over time (BL to FU12/24) were a low MCS BL value (p < .001, OR = 0.925) and a low PCS BL value (p < .001, OR = 0.899), respectively. In opposite, a low chance in MCS improvement was independently associated to RBV containing therapy regimens (p = .015, OR = 0.697) (Table 2). Factors linked to a clinically important decline in MCS were not achieving SVR (p = .003, OR = 0.243), fatigue (p = .023, OR = 1.518), increased GPT values at baseline (p = .005, OR = 0.626) as well as using RBV (p = .001, OR = 1.692). High BL values of PCS (p < .001, OR = 1.060) and low values of MCS (p < .001, OR = 0.973) were associated with clinically important decline in PCS (Table 3).

|

Endpoint (Change in CS FU12/24 vs. BL) |

Subgroup (N) |

Summary Score | Variable | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

||||

|

Clinically important improvement |

Total cohort (1180) |

MCS |

RBV containing vs. RBV free regimen |

0.049; 0.767 (0.590–0.998) |

0.015; 0.697 (0.521–0.933) |

| MCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 0.928 (0.918–0.938) |

<0.001; 0.925 (0.912–0.938) |

|||

|

fatigue vs. no fatigue |

<0.001; 3.089 (2.432–3.924) |

0.475; 0.888 (0.642–1.230) |

|||

| PCS | PCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 0.893 (0.879–0.907) |

<0.001; 0.899 (0.883–0.916) |

||

| MCS BL value continuously |

0.019; 0.990 (0.982–0.998) |

0.084; 1.011 (0.998–1.024) |

|||

|

fatigue vs. no fatigue |

<0.001; 3.030 (2.365–3.881) |

0.067; 1.455 (0.974–2.173) |

|||

|

RBV containing vs. RBV free regimen |

0.015; 1.386 (1.064–1.806) |

0.080; 1.303 (0.969–1.751) |

|

Endpoint (Change in CS FU12/24 vs. BL) |

Subgroup (N) |

Summary score | Variable | Univariate analyses | Multivariate analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

||||

|

Clinically important decline |

Total cohort (1180) |

MCS |

SVR vs. no SVR |

0.009; 0.336 (0.149–0.758) |

0.003; 0.243 (0.097–0.608) |

| MCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 1.049 (1.036–1.061) |

<0.001; 1.063 (1.047–1.080) |

|||

|

fatigue vs. no fatigue |

0.001; 0.636 (0.483–0.836) |

0.023; 1.518 (1.058–2.179) |

|||

|

RBV containing vs. RBV free regimen |

0.005; 1.536 (1.138–2.073) |

0.001; 1.692 (1.230–2.327) |

|||

|

increased GPT vs. normal GPT |

0.007; 0.657 (0.484–0.893) |

0.005; 0.626 (0.452–0.868) |

|||

| PCS | MCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 0.987 (0.969–0.988) |

<0.001; 0.973 (0.963–0.984) |

||

| PCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 1.051 (1.034–1.069) |

<0.001; 1.060 (1.042–1.079) |

|||

|

depression vs. no depression |

0.026; 1.448 (1.045–2.006) |

0.425; 1.156 (0.809–1.652) |

Using today's DAA regimens, SVR is achieved in the far majority of patients without the use of RBV. Therefore, we decided to perform a sub-analysis in this particular group of patients. However, the results were mainly in line with those obtained in the total cohort. Minor differences were only documented with regard to a clinically important decline in MCS. In opposite to the total cohort, fatigue (p = .654) and an increased GPT BL level (p = .159 in univariate regression analysis) were no independent predictors for a further decline after DAA treatment in this subgroup. In contrast, PCS value at baseline was independently linked to MCS decline in these patients (Table S2a,b).

3.5 Clinical parameters associated with clinically important changes among patients with low HRQoL at baseline

As in particular patients with low MCS and PCS BL values seemed to benefit from DAA therapy in terms of HRQoL and at the same time these patients are at the most urgent need for an improvement of HRQoL, further analyses were performed in this particular subgroup (defined as patients with an MCS/PCS BL value in the lower third of the BL values of the overall cohort). Among patients with BL values of MCS in the lower third (n = 379, min = 2 to max = 34, mean = 23), RBV containing therapy regimen was an independent predictor of failing to achieve a clinically relevant improvement in MCS at FU12/24 (p = .01, OR = 0.938). Of note, also lower absolute BL MCS values were independently linked to a higher chance of MCS improvement (p = .021, OR = 0.534) in the multivariate model. Regarding patients with PCS score in the lower third at BL (n = 387, min = 13 to max = 45, mean = 36), none factor remained statistically significant in multivariant regression analyses (Table 4). Further regression analyses were performed for the subgroup of patients with BL values in the lower third in order to identify potential predictors associated even with an achievement of a normative HRQoL (defined as values ≥PCS and MCS mean values of the German normalization cohort23) after DAA. Interestingly, in MCS, depression was determined as the only factor significantly associated with no achievement of normal MCS at FU12/24. Thereby, 92.8% (n = 128/239) of the patients with depression did not achieve normal MCS values after DAA treatment (Table S3).

|

Endpoint (Change in CS FU12/24 vs. BL) |

Subgroup (N) |

Summary Score | Variable |

Univariate analyses |

multivariate analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

||||

| Clinically important improvement |

MCS value at BL in the lower third (379) |

MCS | MCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 0.935 (0.901–0.907) |

0.021; 0.534 (0.314–0.908) |

|

RBV containing vs. RBV free regimen |

0.008; 0.494 (0.294–0.832) |

0.001; 0.938 (0.904–0.974) |

|||

|

PCS value at BL in the lower third (387) |

PCS |

RBV containing vs. RBV free regimen |

0.047; 1.641 (1.007–2.676) |

0.088; 1.539 (0.939–2.523) |

|

| Fatigue vs. no fatigue |

0.028; 2.353 (1.099–5.041) |

0.054; 2.135 (0.988–4.611) |

Finally, we wondered if there are any independent predictors factors could be identified, that are associated with a further decline of HRQoL in the subgroup of patients with already low MCS an PCS values at BL. Multivariate regression analyses identified a BMI > 30 kg/m2 (p = .034, OR = 2.278) and a higher MCS BL value (p < .001, OR = 1.122) as independent risk factors for a clinically important decline in MCS at FU12/24. In contrast, achieving SVR lowered the risk for MCS decline in this population (p = .005, OR = 0.156). No independent predictor could be identified for clinically relevant decline in PCS (Table 5).

|

Endpoint (Change in CS FU12/24 vs. BL) |

Subgroup (N) |

Summary Score | Variable |

Univariate analyses |

multivariate analyses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

p-value; OR (with 95% CI) |

||||

| Clinically important decline |

MCS value at BL in the lower third (377) |

MCS | SVR vs. no SVR |

0.036; 0.270 (0.079–0.918) |

0.005; 0.156 (0.042–0.579) |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 vs. ≤30 kg/m2 |

0.033; 2.214 (1.066–4.599) |

0.034; 2.278 (1.062–4.887) |

|||

| MCS BL value continuously |

<0.001; 1.111 (1.051–1.174) |

<0.001; 1.122 (1.058–1.190) |

|||

|

PCS value at BL in the lower third (387) |

PCS | No significant factor determined |

4 DISCUSSION

This study was performed to investigate the impact of modern DAA regimens on clinically important changes of HRQoL in a large real-world cohort of HCV-infected patients. Patients self-assessed HRQoL was determined by delivering of SF-36 questionnaires at BL, EoT and FU12/24. The outlook for an improvement of HRQoL can help to encourage patient personal treatment motivation, in particular among those with low HRQoL at BL and/or neuropsychological symptoms that might be attributed to HCV infection. However, better BL predictors and robust real-world data not only on statistically but on clinically important changes are required to advise patients in clinical routine. In this study, we confirmed that DAA therapy leads to an overall increase of HRQoL in HCV-infected patients. However, half of the patients failed to gain a clinically relevant improvement and a minority even showed a relevant decline in HRQoL after treatment. Importantly, the chances for a clinically relevant MCS improvement were particularly high among those with low HRQoL scores at BL. Therefore, the benefit of HCV treatment in QoL seems to be particularly high in patients who suffering most. Especially for this subgroup of patients the outlook for an improved HRQoL might be relevant for treatment motivation.

Some considerable differences between MCS and PCS were documented in our study. Clinically important improvement was less likely in PCS compared to MCS. Moreover, in MCS an average clinically important improvement was observed in all considered subgroups, while in PCS an average increase of clinical importance was only observed in the subgroup of patients with BL values in the lower third as well as in the subgroup of patients without any comorbidity. These results may indicate a greater effect of HCV treatment on mental health than on physical health. Appropriately, achieving SVR was independently associated with no decline in MCS at FU12/24. Several clinical DAA trials demonstrated a significant improvement of PCS at FU12,7, 32, 33 but as mentioned before, study population of clinical trials might have limited generalizability compared to the real-world populations. Our results are in line with a smaller real-world study from the Netherlands, reporting likewise absence of a mean clinically important PCS improvement after DAA treatment.34

One explanation for the higher impact on MCS might be, that the diagnosis of HCV infection itself, leads to development of impairment of mental health by being exposed to stigmatization, isolation and discrimination or the necessity of dealing a potentially fatal infectious disease, uncertainty about future progression of the illness and about the success of DAA treatment.35 With clearance of the infection, mentioned concerns could be omitted, what probably leads to an improvement of mental health. Despite the above-mentioned psychogenic stressors, other HCV induced neurocognitive symptoms like decreased concentration, mental slowing, and impaired working memory have been directly linked to HCV infection independent of possibly underlying advanced liver disease.36 Further, intracerebral changes during HCV infection are associated with upregulated inflammatory response, altered neurotransmitter levels, hormonal dysfunction and release of neurotoxic substances, explaining the higher proportion of HCV-infected patients with neuropsychiatric disorders compared to the non-infected population.37, 38 Eradication of the virus by DAA was associated with an improvement of cognitive and mental health domains39 and results from a small study of 39 patients provides evidence that eradication of HCV is associated with improvement of neuropsychological symptoms, which was also correlated with an improvement in HRQoL, assessed by SF-36 questionnaires.15

Although patients with depression seemed to benefit from DAA treatment in mental health, even after treatment of HCV, this group of patients remained to be the group with the lowest mean value of MCS. Further, the performed regression analyses revealed that depression was the only predictor for non-achievement of MCS normalization at FU12/24 for patients with low BL values. As a frequently associated symptom of depressive disorders,40 also fatigue at BL was associated with a further decline in MCS after DAA treatment and showed a tendency towards association with absence of significant improvement in PCS in multivariant regression analyses. These results are in line with a study of Dirks et al., 2016 showing that neuropsychiatric symptoms may persist even after spontaneous eradication of HCV.29 Of course, one may argue that neuropsychiatric diseases like depression or fatigue are multidimensional diseases, but evidence is growing that neuropsychiatric symptoms in HCV-infected patients are associated with alterations in the immune profile,41, 42 with some alterations seem to be long-lasting after the eradication of the virus.43, 44 Despite the above-discussed association of lack of improvement or decline in HRQoL with preexisting depression/fatigue syndrome, a decline in MCS in the entire study cohort as well as an absence of clinically important improvement in MCS in patients with low MCS values was further associated with RBV containing therapy regimens. A lowering effect of RBV on MCS was described before, but remained temporary in other studies during application and was associated with severe side effects such as anemia.7, 34, 45, 46 Therefore, a longer follow-up of the investigated study cohort might likewise lead to the wash out of the above-mentioned effect.

As an independent predictor for a further decline in MCS after DAA therapy, a BMI of >30 kg/m2 was evaluated for patients with low BL values. This finding might be in line with results of previously performed studies, showing weight gain in up to 52% of patients treated with DAA, even among those who are overweight at treatment BL.47, 48 The prevalence of steatosis and steatohepatitis in obese patients was determined before by histological findings in a minimum of 65% and 20%, respectively (notably influenced by ethical background and genetic variation)49 and NAFLD was reported as an independent predictor of poorer HRQoL compared to HCV-infected patients,50 associated with hepatic inflammation levels.51 The absence of improvement or even further decline in MCS therefore may be associated with a coincidently existent NAFLD component in obese HCV-infected patients. Though, evaluation of existing NAFLD in the obese subgroup of patients showing a further decline in MCS was not performed in this study. Therefore, the further decline in mental health may also be explained by other accompanying diseases or psychological stressors of obesity, potentially worsened by further weight gain through DAA treatment.52 As weight gain is common under DAA treatment, patients should therefore be advised prior to DAA treatment and encouragement in dietetic methods should be provided among those at higher risk, in particular.

Our study has some limitations. HRQoL was assessed using the SF-36 questionnaire, which is a generic instrument for the assessment of health-related life quality.23 A combination with a disease-specific questionnaire, like the CLDQ-HCV questionnaire (developed and validated specifically for the assessment of HRQoL in HCV patients)53 might have led to a further elaboration of the results. Especially, in case of fatigue assessment, diagnosis was estimated by scores under the proposed cut-off values in two of SF-36 subscales vitality, social functioning and role.27 A validated questionnaire for the assessment of fatigue severity may have provided more specific results. But as our study was performed in a real-world cohort, with patients not only suffering from HCV infection, a generic tool for the assessment of HRQoL might cover the broadest factors influencing health-related life quality. As data were obtained from the nationwide hepatitis C register, approaches in administration of SF-36 questionnaires might differ between the clinics providing data to the register. Knowledge of SVR status by the patient might differ at the timepoint of completion of SF-36 at FU12/24, and therefore, patients self-assessed HRQoL might be overestimated in some cases due to the euphoria patients experienced by the message of cure of infection like reported by other studies.54, 55 Nevertheless, regarding the high proportion of patients completing DAA intake in our real-world cohort determined study results of HRQoL after receiving DAA therapy regimens might be of high reliability.

In conclusion, our results show an overall improvement in the self-reported HRQoL after DAA-based HCV treatment in a real-world setting, with a clinically important improvement in mental health summary score. This effect was shown for all considered subgroups of patients. Taking the MCID into account, proportion of patients with clinically important changes in both component summary scores decreased, with about half of the patients reported no relevant improvement of HRQoL at FU12/24 after HCV treatment with DAA regimens. Patients with low BL values in HRQoL benefit most of HCV treatment, what especially for this subgroup might be relevant for treatment motivation.

Parameters associated with absence of improvement or further decline in HRQoL were depression, absence of SVR, fatigue, increased GPT levels, ribavirin containing therapy regimens and obesity. Nevertheless, HRQoL is a multidimensional concept and therefore additional reasons, differential diagnosis and possible therapeutic concepts should be considered when a decline in HRQoL is recognized. Further research with longer follow-up is necessary to enhance the follow-up care for patients with a risk of long-term suffering even after clearance of the infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Data were derived from the German Hepatitis C-Registry (Deutsches Hepatitis C-Register, DHCR), a project of the German Liver Foundation (Deutsche Leberstiftung), managed by Leberstiftungs-GmbH Deutschland in cooperation with the Association of German gastroenterologists in private practice (bng) with financial support from the German Center for Infection Research (DZIF) and the companies AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co. KG, Gilead Sciences GmbH, MSD Sharp & Dohme GmbH as well as Bristol-Myers Squibb GmbH & Co. KGaA and Janssen-Cilag GmbH (each until 2020-07-14) and Roche Pharma AG (until 2017-07-14). We thank all study nurses and all study investigators. Statistical analyses were performed by Heike Pfeiffer-Vornkahl from e.factum GmbH.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Valerie Ohlendorf has nothing to disclose. Arne Schäfer reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk and Amgen outside the submitted work. Stefan Christensen: speaker/advisory board member for Abbvie, Camurus, Gilead, Indivior, Janssen, MSD and ViiV. Renate Heyne: sponsored lectures (National or International) Abbvie, Falk, MSD. Uwe Naumann: speaker/advisory board member for AbbVie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Mundipharma, MSD, Roche and ViiV. Ralph Link has nothing to disclose. Christoph Herold: speaker/advisory board member for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Berlin Chemie, BMS, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, NovoNordisk, MSD and Roche. Willibold Schiffelholz has nothing to disclose. Rainer Günther: speaker for AbbVie, Gilead, Roche outside the submitted work. Markus Cornberg reports personal fees from Abbvie, Falk Foundation, Gilead, Janssen-Cilag, GSK, MSD, Spring Bank, SOBI, outside the submitted work. Yvonne Serfert has nothing to disclose. Benjamin Maasoumy: grants/research support from Abbott, Fujirebio, Roche; Personal fees from Abbott, AbbVie, BMS, Janssen, Merck/MSD, Roche, Fujirebio, Astellas. Heiner Wedemeyer: grants/research support from AbbVie, Biotest, BMS, Gilead, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Roche; Personal fees from Abbott, AbbVie, Altimmune, Biotest, BMS, BTG, Dicerna, Gilead, Janssen, Merck/MSD, MYR GmbH, Novartis, Roche, Siemens outside the submitted work. Michael R. Kraus: speaker/advisory board member for AbbVie, Gilead, Janssen, Falk, MSD and MYR Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work.

APPENDIX

1 COLLABORATORS

Hjordis Möller, Karl-Georg Simon, Peter Buggisch, Thomas Lutz, Tim Zimmermann, Hartwig Klinker, Dietrich Hüppe, Ulrich Bohr, Markus Cornberg, Arend Moll, Gerd Klausen, Andreas Weber, Stefan Scholten, Christiane Cordes, Herbert Hillenbrand, Michael Geißler, Manfred Nowak, Marek Stern, Ingolf Schiefke, Katrin Ende, Stefan Zeuzem, Christian Straßer, Gisela Felten, Iris Peuser, Ansgar Rieke, Martin Hower, Nils Postel, Maria-Christina Jung, Thomas Berg, Heinz Hartmann, Stefan Mauss, Christoph Sarrazin, Michael P. Manns, Claus Niederau, Ulrike Protzer, Peter Schirmacher.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.