The association of short and long sleep with mortality in men and women

Summary

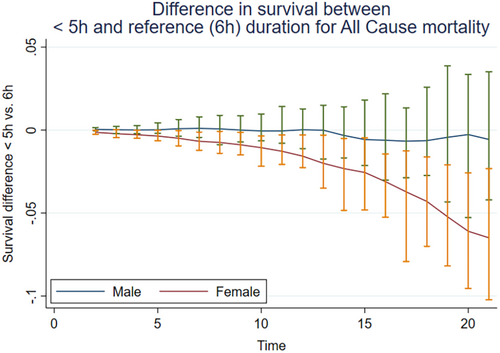

Both short (< 6 hr) and long (> 8 hr) sleep are associated with increased mortality. We here investigated whether the association between sleep duration and all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality differs between men and women. A cohort of 34,311 participants (mean age and standard deviation = 50.5 ± 15.5 years, 65% women), with detailed assessment of sleep at baseline and up to 20.5 years of follow-up (18 years for cause-specific mortality), was analysed using Cox proportional hazards model to estimate HRs with 95% confidence intervals. After adjustment for covariates, all-cause, cardiovascular disease and cancer mortalities were increased for both < 5 hr and ≥ 9 hr sleep durations (with 6 hr as reference). For all-cause mortality, women who slept < 5 hr had a hazard ratio = 1.54 (95% confidence interval = 1.32–1.80), while the corresponding hazard ratio was 1.05 (95% confidence interval = 0.88–1.27) for men, the interaction being significant (p < 0.05). For cardiovascular disease mortality, exclusion of the first 2 years of exposure, as well as competing risk analysis eliminated the originally significant interaction. Cancer mortality did not show any significant interaction. Survival analysis of the difference between the reference duration (6 hr) and the short duration (< 5 hr) during follow-up showed a gradually steeper reduction of survival time for women than for men for all-cause mortality. We also observed that the lowest cancer mortality appeared for the 5-hr sleep duration. In conclusion, the pattern of association between short sleep duration and all-cause mortality differed between women and men, and the difference between men and women increased with follow-up time.

1 INTRODUCTION

Interest in the role of sleep duration in all-cause mortality is widespread. Several meta-analyses have shown significantly increased mortality both among individuals with short (< 6 hr) and long (> 8 hr) sleep durations, compared with a putative optimal (low-risk reference) sleep duration (Cappuccio et al., 2010; da Silva et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2017), resulting in a U-shaped association. One meta-analysis found a significantly increased mortality only for ≥ 9 hr sleep (Liu et al., 2017). However, results vary considerably among individual studies, as does the definition of the reference (“optimal” or “normal”) sleep duration, commonly 7 hr; but 6 hr, as well as 7–8 hr, or 8 hr have been used. With regard to major causes of death, both short and long sleep have been associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) excess mortality (Cappuccio et al., 2011; Kwok et al., 2018), but increased cancer mortality has only been linked to long sleep (≥ 8 hr; Li et al., 2019; Stone et al., 2019). Notably, virtually all studies have employed the respondents’ “usual” sleep duration in their analyses, which likely refers to workdays, as the latter make up the majority of days for most adult individuals.

We have previously shown that the increased all-cause mortality associated with short and long sleep becomes more pronounced in older individuals (Akerstedt, Narusyte, & Svedberg, 2021; Akerstedt, Trolle-Lagerros, et al., 2021). In addition, the pattern of association may differ between men and women. Women, for example, complain more of sleep problems than men (Groeger et al., 2004), sleep longer, and wish to sleep more (Polo-Kantola et al., 2016). However, only a few studies have statistically analysed whether the pattern differs between men and women, that is, analysed whether there is a significant interaction with sex in the association between sleep duration and mortality. Thus, one large study (Tao et al., 2021) found a significant interaction for sex and sleep duration, although the source of the interaction was not identified. Still, it appears from the hazard ratios (HRs) that men who had a short sleep duration (< 5 hr) had a higher mortality than women. Ren et al. (2020) found a significant interaction, but combined < 5 hr, 5 hr and 6 hr sleep durations, which precludes conclusions on shorter sleep. Finally, a large Asian cohort did not find any significant interaction between men and women in all-cause mortality, but figures suggest a somewhat higher HR for women who had a short sleep duration compared with men (Svensson et al., 2021).

Among the major causes of death, one study (Tao et al., 2021) found no significant interaction for CVD mortality between men and women. Svensson et al. (2021) found a steeper rise in CVD mortality following long and short sleep for women than men. For cancer mortality, the study by Tao et al. (2021) found a steeper rise from the reference sleep duration to long (≥ 9 hr) and short (< 5 hr) sleep in men than for women. Svensson et al. (2021) found a significant interaction, but its characteristics could not be interpreted from the figure.

Taken together, only a few studies have formally investigated if the pattern of association between sleep and mortality differs between men and women, and in these few studies the source of an observed disparity has not been formally investigated. Our purpose was to investigate if men and women show different patterns of association for short or long sleep duration and all-cause mortality, and to formally test the source of observed differences. We also included CVD and cancer mortality as outcomes.

2 METHODS

2.1 Design and participants

We used data from the Swedish National March Cohort (SNMC), designed to investigate the association between lifestyle factors and risk of chronic diseases (Trolle Lagerros et al., 2017). The cohort was established in 1997 as a part of a fund-raising activity of the Swedish National Cancer Society. In different places around Sweden, participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire regarding demographics, lifestyle and health. In addition, they filled in their individually unique national registration number assigned to all registered residents in Sweden. This number was subsequently used to link the cohort to the national Swedish registers to identify the health outcomes of interest. The national registration number uses a binary identification of male or female sex, and we will use the latter term forthwith, rather than “gender”, even if results may well be linked to both the sociocultural context (i.e. gender) and biological sex.

A total of 43,865 subjects filled out the questionnaire. We excluded those with an incorrect national registration number, inconsistent answers, wrong data on age, < 18 years of age, and those who emigrated before start of follow-up. This left 42,063 individuals, who were prospectively followed for all-cause, CVD and cancer mortalities. Follow-up started on 1 October 1997 and ended at death, emigration or on 26 April 2018, whichever occurred first. However, for CVD and cancer mortality the follow-up ended on 31 December 2016. The mean ± SD of the follow-up time for all-cause mortality was 18.3 ± 4.1 years. The shortest and longest follow-up time was 0.03 (11 days) and 20.6 years, respectively. The response rate could not be determined because it is unknown how many subjects originally were given a questionnaire. A total of 7752 individuals were excluded due to missing data on sleep duration or covariates, with the highest loss for smoking (n = 3522). This left 34,311 participants for analyses. In total 27,389 participants were censored and their mean follow-up time was 19.25 years, 6463 were censored for death (13.1 ± 0.07 years), and 459 (7.50 ± 5.54 years) for emigration. Mean age ± SD for the final sample was 50.5 ± 15.5 years and 65.0% were women. The Regional Ethical Review Board of Stockholm approved the study. All participants gave informed consent.

2.2 Variables

The national registration numbers were linked to the Swedish Cause of Death Registry, held by the National Board for Health and Welfare. The number of deaths during the follow-up period was 9261 (6463 after exclusion of participants). CVD (ICD-10 codes I00–I99, N = 1863) and cancer (ICD-10 codes C00–C97, N = 2267) were the most common causes of death.

We used the Karolinska Sleep Questionnaire to assess sleep duration and other aspects of sleep (Akerstedt et al., 2008). We were particularly interested in the question “How many hours, approximately, do you usually sleep during a weekday night?” The response alternatives were < 5, 5, 6, 7, 8 or ≥ 9 hr.

We adjusted for the following potential confounders: sex, age, marital status (unmarried/never married, divorced, widowed) versus married/cohabiting, Charlson Comorbidity Index (based on prevalence of major diseases, and scaled as 0, 1 ≥ 2; Charlson et al., 1987), educational level (university versus high school and compulsory school), smoking (current versus previous/never), body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared), exercise (0–2 hr versus 3–4 hr, 5–6 hr, > 6 hr per week), coffee consumption (number of cups per day), alcohol consumption (gram alcohol, estimated from questions on type, frequency and amount of beverage), cancer, CVD, diabetes, hypertension, loud snoring (never, seldom, sometimes, mostly, always), naps (never, seldom, sometimes, mostly, always) and use of sleep medication (never, seldom, sometimes, mostly, always).

We used the following variables to further describe baseline characteristics: poor sleep quality (very good, rather good, neither good, nor poor, rather poor, very poor), unrefreshed at awakening (never, seldom, sometimes, mostly, always), sleep duration during weekends/days off (< 5, 5, 6, 7, 8, ≥ 9 hr) and needed sleep duration (< 5, 5, 6, 7, 8, ≥ 9 hr).

2.3 Statistical analysis

Summary characteristics of baseline variables are presented by categories of sleep duration and sex. Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to estimate mortality HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), in categories of sleep duration compared with the reference. This was done separately for long and short sleep durations. The reference duration was selected as the one with the lowest HR for the fully adjusted analysis, including both men and women. Participants were followed-up from baseline to death, emigration or end of study, whichever came first. Separate analyses were carried out for all-cause, CVD and cancer mortalities. The time scale used in the Cox regression analysis was time from start of follow-up. Cox regression proportional hazards assumption was tested through formal statistical tests based on the Schoenfeld residuals and, if found, was corrected through stratification for such a variable. In the analyses we assumed that data were missing at random.

Primarily we analysed the role of sex as an effect modifier in the association between short or long sleep and mortality. This was assessed through the inclusion of interaction terms for short sleep and long sleep separately (both referred to the same reference sleep duration). We use the term “interaction” here in its strict statistical sense, with full awareness that sex is not a variable that can normally be manipulated, which the term implies. The results were statistically evaluated using both the Wald test and the likelihood ratio test.

If a significant difference was indicated in the Cox regression, the survival probability for each 1-year follow-up interval was computed from the fully adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves for the sleep duration responsible for the interaction and the reference sleep duration. This was done for each sex. The difference in survival probability between the two sleep duration groups was then calculated for each time point. The CIs for the differences were estimated using bootstrap sampling with 50 replications. Finally, the interaction between sex and follow-up time for the difference values was obtained through regression analysis.

Four sensitivity analyses were carried out. First, in order to investigate possible reverse causality, the first 2 years of follow-up were excluded. Second, Fine–Grey proportional hazards regressions were performed on the association between sleep duration and CVD and cancer mortality, adjusting for all confounders, considering the competing risk of death (Fine & Gray, 1999). Third, the material was re-analysed after exclusion of health variables, as there might be a risk of over-controlling. Fourth, we used the mean (weighted weekday and weekend) sleep duration, instead of weekday sleep, in re-analyses of the data. Stata 16.1 was used for statistical analysis.

3 RESULTS

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics for women and men, stratified by sleep duration. Among the shortest sleepers (< 5 hr), women used sleep medication more often, reported poorer sleep quality, and less restoration on awakening, compared with men. Among the longest sleepers (≥ 9 hr) there was a preponderance of retired men.

| Sleep durations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women/men | < 5 hr Mean ± SD or % | 5 hr Mean ± SD or % | 6 hr Mean ± SD or % | 7 hr Mean ± SD or % | 8 hr Mean ± SD or % | ≥ 9 hr Mean ± SD or % |

| N | 611/374 | 1077/622 | 4938/3058 | 9764/5217 | 5405/2494 | 517/234 |

| Age (years) | 58.2(15.6)/56.7(19.3) | 55.1 (14.1)/49,9 (17.3) | 50.7 (14.0)/49.8 (16.0) | 48.2 (14.0)/51.8 (15.8) | 47.8 (15.8)/55.7 (17.4) | 47.7 (17.8)/59.6 (17.5) |

| BMI (kg m−2) | 24.9 (3.9)/25.4 (3.4) | 24.9 (4.2)/25.6 (3.8) | 24.9 (4.2)/25.2 (3.1) | 24.2 (3.6)/24.9 (2.9) | 24.2 (3.6)/25.0 (3.1) | 24.9 (4.3)/25.0 (3.0) |

| Married + cohabiting% | 48.0/40.9 | 42.1 /44.5 | 40.2/38.7 | 37.6/32.7 | 39.1/30.9 | 46.0/31.6 |

| Exercise ≥ 5 hr per week % | 60.7/53.5 | 59.2/49.8 | 58.0/50.6 | 55.2/51.4 | 55.6/57.0 | 53.0/56.8 |

| Education: Univ % | 19.8/17.4 | 29.1/28.8 | 38.0/33.6 | 40.6/37,7 | 33.5/31,5 | 27.1/26.9 |

| Smoking, current % | 12.3/8.8 | 9.7/9.3 | 11.1/7,7 | 8.1/5.4 | 7.2/6.0 | 7.5/5.6 |

| Coffee ≥ 5 cups per day | 15.5/23.3 | 19.0/25.9 | 17.5/25.4 | 14.9/19.4 | 12.2/16.7 | 12.6/14.1 |

| Alcohol (g per month) | 223(355)/662(1392) | 247(355)/585(893) | 264 (330)/576(1515) | 258 (319)/496(597) | 247 (321)/468(752) | 232 (330)/532(776) |

| Cancer at baseline% | 9.8/7.8 | 9.0/4.0 | 6.6/4.2 | 6.1/4.4 | 6.5/6.4 | 8.5/11.1 |

| CVD at baseline % | 14.7/23.5 | 9.2/14.8 | 8.6/12.3 | 6.9/12.5 | 6.8/17.4 | 9.1/26.5 |

| Sleep duration, days off hr | 4.9 (1.5)/5.1 (1.7) | 6. 2 (1.3)/6.5 (1.4) | 7.3 (1.1)/7.2 (1.1) | 7.9 (0.8)/7,7 (0.8) | 8.3(0.7)/8,2 (0.7) | 8.8 (0.7)/8.8 (0.7) |

| Sleep need hr | 6.8 (1.2)/6.7 (1.3) | 6.7 (1.0)/6.3 (1.1) | 7.1 (0.8)/6.8 (0.9) | 7.6 (0.6)/7.3 (0.6) | 8.1 (0.5)/7.9 (0.5) | 8.7 (0.5)/8.6 (0.6) |

| Day work % yes | 31.9 /31.8 | 44.3/48.9 | 59.3/56.6 | 66.6/57.1 | 58.2/39.5 | 42.7/21.8 |

| Employed % yes | 26.7/30.2 | 42.2/56.6 | 54.7/60.1 | 55.5/56.7 | 44.4/35.0 | 24.4/16.7 |

| Retired % yes | 44.2/47.1 | 31.5/24.4 | 19.8/21.1 | 15.3/26.8 | 20.5/45.0 | 25.5/62.0 |

| Physical exercise ≥ 4 times per week % | 27.8/26.2 | 26.8/28.8 | 25.9/24.0 | 21.6/22.6 | 22.1/21.5 | 19.7/13.7 |

| Hypnotics (sometimes–always) % | 23.9/13.4 | 19.0/7.7 | 8.2/3.8 | 4.2/2.3 | 3.3/2.1 | 6.1/4.2 |

| Napping (sometimes–always) % | 11.3/15.5 | 5.9/8.7 | 5.7/7.7 | 5.2/8.4 | 6.5/14.5 | 20.2/35.1 |

| Poor sleep quality (rather poor + very poor) % | 46.0/23.0 | 42.3/24.7 | 12.5/7.7 | 2.9/1.8 | 1.6/1.3 | 3.6/3.0 |

| Unrefreshed at awakening (sometimes–always) % | 70.7/54.8 | 81.9/55.3 | 74.8/74.8 | 64.0/65.1 | 50.6/41.3 | 53.0/40.2 |

| Loud snoring (sometimes—always) % | 23.8/42.8 | 21.6/43.4 | 21.9/43.5 | 20.7/41.5 | 21.4/41.6 | 24.2/42.3 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index % > 0 | 23.9/18.7 | 17.2/14.8 | 13.0/12,4 | 10.2/12.7 | 10.9/16.2 | 11.8/29.1 |

- Note: All comparisons across sleep durations are significant at p < 0.001 regardless of sex.

- Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

The assumption of proportionality was violated for age for all Cox regression analyses. We therefore stratified by age in all analyses.

Table 2 shows the results for all-cause mortality. For the full sample with full adjustment, we found significantly increased mortality both among those with short sleep (HR = 1.28 [CI = 1.14–1.44]) and long sleep (HR = 1.29 [CI = 1.12–1.50]). The overall interaction for short sleep durations (< 5 hr, 5 hr and reference [6 hr]) and sex was significant (p < 0.05), with a higher HR for women than for men for the < 5 hr duration. The interaction for long sleep durations (≥ 9 hr, 8 hr, 7 hr) and reference (6 hr) by sex was not significant (p > 0.05). For women, we found a significantly increased HR (1.54 [95% CI = 1.32–1.80]) for short and long (1.30 [95% CI = 1.04–1.61]) sleepers, respectively. For men, we only found a significant HR for long sleep (1.28 [95% CI = 1.05–1.56]). For unadjusted results, please see supplementary Table S1.

| N/cases | Full sample HR (95% CI) adjusted for age | Full sample HR (95% CI) fully adjusted, interaction tested | Women HR (95% CI) fully adjusted, except for sex | Men HR (95% CI) fully adjusted except for sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/cases | 34,311/6463 Ns = 10,680/2194 Nl = 31,627/5669 |

Nt = 33,526/6186 Ns = 10,646/2142 Nl = 31,549/5645 |

Nt = 21,803/3083 Ns = 6604/1220 Nl = 20,572/2748 |

Nt = 11,724/3103 Ns = 4042/962 Nl = 10,977/2897 |

| Sleep duration | ||||

| < 5 hr | 1.45 (1.29–1.62) | 1.28 (1.14–1.44)* | 1.54 (1.32–1.80) | 1.05 (0.88–1.27) |

| 5 hr | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 1.01 (0.90–1.14) | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) | 0.91 (0.76–1.10) |

| 6 hr | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 hr | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 1,01 (0.94–1.08) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) |

| 8 hr | 1.06 (0.98–1.13) | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 1.10 (1.00–1.22) | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) |

| ≥ 9 hr | 1.46 (1.26–1.68) | 1.29 (1.12–1.50) | 1.30 (1.04–1.61) | 1.28 (1.05–1.56) |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Nl, N for long sleep; Ns, N for short sleep; Nt, N for the total group.

- Note: Bold = significant HR (p < 0.05 or more). Note that N of the reference value is included in the N for both short and long sleep analyses. Column 1 is adjusted for sex only. Column 2 is adjusted for all covariates at baseline: age, sex, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, education, smoking, BMI, exercise, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, loud snoring, napping, hypertension, CVD and cancer, and diabetes, hypertension and sleep medication. Columns 3 and 4 are adjusted for the same variables as column 3, except for sex. Multiplicative interaction tested in the full sample with full adjustment. Stratification for age.

- * Significant interaction, p < 0.05.

Table 3 shows a significantly increased CVD mortality for short sleep duration (HR = 1.30 [CI = 1.07–1.59]) as well as for long sleep duration (HR = 1.55 [CI = 1.22–1.79]) in the fully adjusted analyses. The interaction between sex and short sleep durations was significant (p < 0.05), but not between sex and long sleep durations (p > 0.05). After stratification for sex, women showed significant HRs for short (1.71 [95% CI = 1.31–2.49]) and long (1.53 [95% CI = 1.10–2.43]) sleep durations. Men did not show any significant association between sleep duration and CVD mortality. For unadjusted results, please, see supplementary Table S3.

| Full sample HR (95% CI) adjusted for age | Full sample HR (95%% CI) fully adjusted, interactions tested | Women HR (95%% CI) fully adjusted, except for sex | Men HR (95%% CI) fully adjusted, except for sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/cases | 34,311/1863 Ns = 10,680/670 Nl = 31,627/1582 |

Nt = 33,527/1767 Ns = 10,646/669 Nl = 31,627/1582 |

Nt = 21,803/787 Ns = 6604/349 Nl = 20,572/670 |

Nt = 11,724/980 Ns = 4042/320 Nl = 10,977/904 |

| Sleep duration | ||||

| < 5 hr | 1.51 (1.25–1.84) | 1.30 (1.07–1.59) | 1.71 (1.31–2.49) | 1.02 (0.80–1.47) |

| 5 hr | 1.21 (0.99–1.47) | 1.22 (1.00–1.48) | 1.39 (1.06–1.82) | 1.09 (0.80–1.47) |

| 6 hr | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 hr | 1.04 (0.92–1.18) | 1.04 (0.92_1.18) | 1.02 (0.84–1.23) | 1.03 (0.86–1.22) |

| 8 hr | 1–04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.04 (0.91–1.19) | 1.13 (0.92_1.39) | 0.98 (0.81–1.18) |

| ≥ 9 hr | 1.56 (1.22–1.99) | 1.55 (1.22–1.79) | 1.53 (1.10–2.43) | 1.28 (0.92–1.79) |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Nl, N for long sleep; Ns, N for short sleep; Nt, N for the total group.

- Note: Bold = significant HR (p < 0.05 or more). Note that N of the reference value is included in the N for both short and long sleep analyses. Column 1 is adjusted for sex only. Column 2 is adjusted for all covariates at baseline: age, sex, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, education, smoking, BMI, exercise, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, loud snoring and napping, hypertension, CVD and cancer, and diabetes, hypertension and sleep medication. Columns 3 and 4 are adjusted for the same variables as column 3, except for sex. Interaction sex × sleep duration tested in the full sample with full adjustment. Stratified for age.

For cancer mortality (Table 4), the fully adjusted analysis for the full sample shows significantly increased HRs for the short (1.84 [95% CI = 1.39–2.46]) and long (1.51 [95% CI = 1.11–2.08]) sleep durations, with no significant interaction by sex (p > 0.05 for each analysis). After stratification for sex, women showed a significant HR for the short (1.77 [95% CI = 1.24–2.51]) sleep duration, as did men (1.92 [95% CI = 1.11–3.31]). Men showed significant HRs for most durations above the reference, with HR = 2.11 (95% CI = 1.25–3.40) for the ≥ 9 hr duration. In addition, the linear increase from 5 hr to ≥ 9 hr was significant (p < 0.003) when sleep duration was analysed as a continuous variable. For unadjusted results, please see supplementary Table S4.

| Full sample HR (95% CI) adjusted for age | Full sample HR (95% CI) fully adjusted, interactions tested | Women HR (95% CI) fully adjusted, except for sex | Men HR (95% CI) fully adjusted, except for sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/cases | 34,311/2267 Ns = 2684/210 Nl = 33,326/2155 |

Nt = 33,527/2194 Ns = 2667/205 Nl = 33,240/2147 |

Nt = 21,803/1195 Ns = 1677/135 Nl = 21,645/1166 |

Nt = 11,724/999 Ns = 990/70 Nl = 11,595/991 |

| Sleep duration | ||||

| < 5 hr | 1.81 (1.37–2.38) | 1.84 (1.39–2.46) | 1.77 (1.24–2.51) | 1.92 (1.11–3.31) |

| 5 hr | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 hr | 1.21 (0.98–1.51) | 1.24 (0.99–1.54) | 1.06 (0.81–1.38) | 1.58 (1.06–2.35) |

| 7 hr | 1.33 (1.08–1.64) | 1.37 (1.10–1.69) | 1.14 (0.88–1.48) | 1.76 (1.18–2.55) |

| 8 hr | 1,47 (1.19–1.82) | 1.48 (1.19–1.84) | 1.24 (0.95–1.63 | 1.84 (1.25–2.73) |

| ≥ 9 hr | 1.67 (1.22–2.27) | 1.51 (1.11–2.08) | 1.18 (0.77–1.81) | 2.06 (1.25–3.40) |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; Nl, N for long sleep; Ns, N for short sleep; Nt, N for the total group.

- Note: Bold = significant HR (p < 0.05 or more). Note that N of the reference value is included in the N for both short and long sleep analyses. Column 1 is adjusted for sex only. Column 2 is adjusted for all covariates at baseline: age, sex, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, education, smoking, BMI, exercise, coffee consumption, alcohol consumption, loud snoring and napping, hypertension, CVD and cancer, and diabetes, hypertension and sleep medication. Columns 3 and 4 are adjusted for the same variables as column 3, except for sex. Interaction sex × sleep duration tested in the full sample. Stratified by age.

To reduce the risk of reverse causality, we repeated the analyses following exclusion of the first 2 years of follow-up in a sensitivity analysis. This restriction did not affect the results for all-cause, CVD or cancer mortality more than marginally (supplementary Tables S2–S4). The interaction by sex remained significant for short sleep (p < 0.05) for all-cause mortality, but not for CVD mortality (p > 0.05). In a second sensitivity analysis, we found that the sub-hazard ratios of the Fine–Grey competing risk analysis were substantially equivalent to the Cox HRs (see supplementary Tables S5 and S6). The interaction term for CVD mortality did not remain significant for short sleep (p > 0.05).

In a third sensitivity analysis, we repeated the main analyses in Tables 2–4, using average weekly sleep (weekday and weekend weighted in the proportion 5/2). The results for all-cause mortality were virtually identical to those of weekday data (Table S7). The same analysis with CVD mortality as outcome resulted in the significant effect of long sleep duration (≥ 9 hr) being lost for the entire sample and for women (Table S8). However, the interaction for short sleep became significant, with somewhat higher HRs for women. With cancer mortality as outcome, the results were somewhat attenuated and the significant HR for short sleep in men was lost. Because chronic conditions such as diabetes type 2 and others can be associated with poor sleep, we made a fourth sensitivity analysis without adjustment for Charlson Comorbidity Index, diabetes II, cancer and hypertension. This analysis yielded only marginal effects on the second decimal digit of the HR (not shown).

To understand the influence of follow-up time on all-cause mortality for the short sleepers, we carried out a survival analysis for the 6 hr (reference) and < 5 hr (short) sleep duration for men and women separately. Next, we computed the difference in survival between the two sleep durations, separately for men and women, and we conducted a regression analysis of sex by follow-up time. The difference in survival between < 5 hr duration and the reference (6 hr) sleep duration showed a significant interaction between sex and follow-up time of t = 14.51, p < 0.001 for all-cause mortality. Women with short sleep showed a gradual reduction in survival, compared with the reference duration, while men with short sleep essentially showed no change with follow-up time (Figure 1).

In order to explore if the sex differences in rated sleep problems for the different sleep durations (in Table 1) were significant, we carried out a logistic regression analysis using sleep duration and sex as predictors, with poor ([= poor + very poor] and good [= very good + good + neither good, nor poor; reference]) sleep as outcome. This analysis indicated that women rated a poorer sleep quality with shorter sleep than men (p <0.05).

4 DISCUSSION

In this large, prospective cohort study, the association between weekday sleep duration and mortality differed significantly by sex for all-cause mortality, with women exhibiting a higher risk for the < 5 hr sleep duration compared with men. The sex-related difference in survival increased with follow-up time for all-cause mortality. For CVD and cancer mortality, no sex difference was seen. Both long and short sleep duration in the full sample were associated with increased all-cause, CVD and cancer mortalities. For women, significant HRs were seen for < 5 hr and ≥ 9 hr sleep durations with respect to all-cause and CVD mortality, but in men only the HR for ≥ 9 hr sleep duration was significant. For cancer mortality, men had a significant linear increase in HR from the reference (5 hr) to the long sleep (≥ 9 hr) duration, while both men and women had a significantly increased risk for short sleep. Using average (weekday and weekend) sleep duration in the analyses did not affect results for all-cause mortality, but did modify the results for CVD and cancer mortality.

The main question addressed in the present study was if sex modified the association between mortality and short or long sleep. Our finding of a significant interaction by sex for all-cause mortality agrees with the large study by Tao et al. (2021). However, even if the source of the disparity was not tested in that study, the figures suggest a higher risk for men who had a short sleep duration. The reason for the difference between that study and the present one is difficult to ascertain. However, beyond effects of possible differences in adjustment for covariates, or in cultural influences, follow-up time was relatively short (10.5 years) in the study by Tao et al. (versus 20.5 years in the present study), which may have cancelled out sex differences, which gradually increased during follow-up in the present study (up to 20.5 years). The large Asian cohort study by Svensson et al. (2021) found no significant sex difference, but the figures suggest a higher risk for women who had a short sleep duration.

The finding of an increased mortality for women who had a short sleep duration should also be seen in relation to the higher frequency of sleep problems and use of hypnotics in that group. This suggests that the women suffered more from lack of sleep. Women often report longer sleep than men (Groeger et al., 2004; Leger et al., 2014), which may make short sleep more stressful in women than in men. Unfortunately, we do not know if women in the cohort had a higher frequency of anxiety or other mental health problems, leading to the higher use of hypnotics.

Men with short sleep did not show a significantly increased all-cause mortality. The meta-analysis of Liu et al. (2017) made the same observation, while da Silva et al. (2016) found no significant HR for short sleep for either sex, and Yin et al. (2017) found significant, but only slightly increased HRs for both sexes (1.06 and 1.07 for men and women, respectively), and Cappuccio et al. (2010) found significant excess mortality HRs for both sexes (1.17 and 1.09 for men and women, respectively). The lower rating of poor sleep quality among men who had a short sleep duration indicates that men with short sleep do not seem to perceive their sleep as poor. There is also a lower use of hypnotics among men who had a short sleep duration, and the use of hypnotics has been linked to higher mortality in our cohort (Hedstrom et al., 2020), as well as in other studies (Kripke, 2016).

The difference between men and women in the pattern of association between sleep duration and mortality raises the question of possible biological and sociocultural (gender) influences. Previous work has demonstrated negative effects on women's sleep of, for example, oestradiol variations (Mong & Cusmano, 2016; but no data exist on links to longevity), and sleep duration in women is negatively affected by parental duties, occupational load and role expectations in society (Decker et al., 2022). Unfortunately, the present data set did not contain variables that could shed light on gender influences.

With respect to CVD mortality, the interaction short sleep duration by sex was not significant after exclusion of the first 2 years of follow-up, or after the competing risk analysis. These findings are in agreement with one previous study (Tao et al., 2021), but disagree with another (Svensson et al., 2021). With regard to cancer mortality, we found no significant difference by sex. Tao et al. (2021) and Svensson et al. (2021) found significant sex differences, but did not test what durations of sleep that drove the disparity. Thus, at present, we lack conclusive evidence whether sleep duration affects CVD and cancer mortality in women and men.

It should be noted that the reference sleep duration for cancer mortality (with full adjustment) was unexpectedly short (5 hr). However, this may be in line with the studies by Tao et al. (2021) and Svensson et al. (2021), which found non-significantly increased HRs for 6 hr and ≤ 5 hr sleep durations in addition to that of the chosen reference (7 hr). These observations suggest that optimal (reference) sleep duration may differ between cause-specific mortalities, but that this possibility needs further research. The variability of the optimal sleep duration between different outcomes was also highlighted in the US Sleep Foundation report on sleep recommendations (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015).

Using the average weekly sleep duration as a predictor was not sufficient to change the main results for all-cause mortality, although some attenuation was seen. This is not contrary to the previous study (Akerstedt et al., 2018) as sleep duration in that study was subdivided into combinations of long and short sleep on weekdays and weekends. For CVD and cancer mortality, however, some changes were seen that could mean that using average sleep duration may lead to a conclusion that long sleep is not associated with increased mortality, and that short sleep in men is not associated with increased mortality. However, the effects were modest and we lack studies to compare with. Further work is needed for conclusions.

Among limitations, one concern is that the exposure variables were measured only at baseline and not repeatedly during follow-up. It is possible that sleeping patterns have changed during follow-up. Such misclassification has likely biased risk estimates towards the null and thus entailed underestimation of any causal effect. Another concern is the use of self-reported data for sleep duration. Strengths of the present study include the size of the cohort, the long and virtually complete follow-up, the analysis stratified by sex and the use of competing risk analysis.

In conclusion, we found a significant difference by sex between sleep duration and all-cause mortality. Women with short sleep exhibited higher risk than men. The difference increased with increasing follow-up time. For CVD a similar pattern was seen, but not supported after sensitivity analyses. For cancer mortality, the interaction by sex and sleep duration was not significant, but the risk was increased for short sleep in both women and men, and for long sleep in men. Using average sleep duration (across the week) instead of weekday sleep duration only modified cause-specific outcomes.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Torbjörn Åkerstedt conceived of the study and wrote the first draft. Linnea Widman and Julia Eriksson analyzed the data. Ylva Trolle Lagerros, Rino Bellocco, Hans-Olov Adami and Weimin Ye critically commented on the design and manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The present study was supported by The Tercentenary Fund of Bank of Sweden. Ylva Trolle Lagerros was supported by Region Stockholm (clinical research appointment). According to Swedish data legislation, cohort data are not publicly available, and access to data can only be made upon request. The request should be addressed to the principal investigators YTL, RB and WY, and will be handled on a case-by-case basis. Any sharing of data will be regulated via data transfer and use agreement with the recipient.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None of the authors has declared competing interests, financial or other.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

According to Swedish data legislation, cohort data are not publicly available, and access to data can only be made upon request. The request should be addressed to the principal investigators YTL, RB, and WY and will be handled on a case-by-case basis. Any sharing of data will be regulated via data transfer and use agreement with the recipient.