A multicomponent herbal feed additive improves somatic cell counts in dairy cows - a two stage, multicentre, placebo-controlled long-term on-farm trial

Abstract

In contrast to natural and historical diets of wild and domesticated ruminants, the diversity of plant species is limited in diets of modern dairy cows. Are “production diseases” linked to this? We conducted a trial to test the effects of a multicomponent herbal feed additive (HFA) on health, performance and fertility traits. A dose-finding study (DF) with 62 cows on 11 commercial farms compared a low (50 g) and a high (100 g) dose of HFA (HFA-50, HFA-100) with a placebo (PL). In a subsequent field trial (FT) with 280 cows on 30 commercial farms, HFA-100 was compared to PL. Cows were randomly assigned to HFA and PL groups and received HFA or PL individually daily from 14 days pre- to 300 days post-calving. Data were analysed with mixed effects models. No differences between HFA and PL were found regarding performance, body condition score and overall culling rates. A tendency towards lower milk urea for HFA-100 compared to PL (p = .06) was found in DF. HFA significantly reduced elevated milk acetone observations (≥10 mg/L) in the first 10 lactation weeks (HFA-100: 4%; HFA-50: 4%; PL: 12%) in DF. HFA-50 significantly reduced lameness incidence (HFA-100: 11%; HFA-50: 2%; PL: 14%) in DF. Calving intervals were 15 days shorter in HFA compared to PL in both trials, which could be confirmed by tendency (p = .07) in FT. In both trials, the proportion of test days with elevated somatic cell score (≥3.0) was significantly lower in HFA compared to PL (DF: HFA-100: 40%, HFA-50: 45% and PL: 55%; FT: HFA-100: 38% and PL: 55%) which is also reflected by tendency (p = .08) in lower culling rates due to udder diseases in FT. HFA showed no negative impact on any of the measured parameters. The effects of HFA indicate a potential of phytochemically rich and diverse feed additives for dairy cows' nutrition and physiology.

1 INTRODUCTION

Ruminants have evolved in environments which were rich in different plant species in all possible phenological stages. Typical herbs present in the diet of cattle grazing on natural pastures contain a broad spectrum of secondary metabolites (phytochemicals), such as various phenolic compounds, essential oils and alkaloids (Cornu et al., 2001; Fraisse et al., 2007; Jayanegara, Marquardt, Kreuzer, & Leiber, 2011). There is evidence that selection behaviour (Villalba, Provenza, & Han, 2004), digestion (Cobellis, Trabalza-Marinucci, & Yu, 2016) and endogenous metabolic processes (McGrath et al., 2018; Oh, Wall, Bravo, & Hristov, 2017) of cattle are adapted to these phytochemicals which represented their biochemical environment during evolution and historical domestication. However, the biochemical composition of contemporary dairy rations is likely to differ from that. In order to achieve high nutrient density and digestibility, diets consist of high yielding varieties of few grass and legume species, whole-plant maize, as well as concentrates based on cereals, corn and grain legumes. They all contain high concentrations of crude protein, and easily degradable carbohydrates, but are rather low in phytochemicals. It is not unlikely that with the narrow botanical and biochemical spectrum of these intensive diets important functions of phytochemicals for rumen control (Buccioni, Decandia, Minieri, Molle, & Cabiddu, 2012; Cobellis et al., 2016; Mendel, Chlopecka, Dziekan, & Karlik, 2016), lipid metabolism (Khiaosa-ard et al., 2009; Leiber, Willems, Werne, Ammer, & Kreuzer, 2019), antioxidative protection, immune factors and hormone regulation (Oh et al., 2017) have been lost. The implications of this loss for animal health are not yet sufficiently understood.

A wide spectrum of plants rich in phytochemicals has been used traditionally by farmers, pharmacists and veterinarians to treat and prevent cattle diseases (Fröhner, 1900; Remer-Bielitz & Seelbach, 2001; Stucki et al., 2019). In European regions with smaller-scaled farms, specific “healthy fodder” plants are still used (Vogl, Vogl-Lukasser, & Walkenhorst, 2016), and in ethnoveterinary surveys, “general strengthening” is a frequently reported indication for the use of medicinal plants (Bischoff et al., 2016; Disler et al., 2014; Mayer, Vogl, Amorena, Hamburger, & Walkenhorst, 2014; Mayer et al., 2017; Schmid et al., 2012; Stucki et al., 2019).

An increasing body of scientific investigations on the mode of action of phytochemicals supports several of the traditional uses of herbs in animals (Ayrle et al., 2016; Mayer et al., 2014; Rochfort, Parker, & Dunshea, 2008; Walkenhorst et al., 2014). Considering the high incidence of dairy cows' “production disease” complexes linked to metabolism, the musculoskeletal system, fertility and udder health (Knaus, 2009), the use of plants rich in phytochemicals should be considered more seriously as a preventive and therapeutic option.

Even though the traditional administration of medicinal plants to individual cows may currently be highly limited, the market in feed additives such as minerals, trace elements and vitamins is large, and plants rich in phytochemicals are gaining importance (Hashemi & Davoodi, 2011; Karaskova, Suchy, & Strakova, 2015). Such products are often promoted with promises of partial or complete improvement of health problems in dairy cows. The European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) defined requirements for efficacy studies in feed additives for livestock (EFSA, 2011), but the number of herbal products for dairy cows that have been evaluated under controlled and realistic conditions of commercial farms is small. The same is true with regard to studies that focus on specific health aspects of phytochemicals in ruminants (Kumar, Mehla, & Meena, 2011; Olagaray et al., 2019; Rochfort et al., 2008).

In response to the lack of knowledge regarding phytochemical effects on the general health and constitution of cows under practical conditions, we designed a two-stage, multicentre, long-term placebo-controlled on-farm trial. We tested the effects of a commercial multi-herbal feed additive on health and performance parameters in dairy cows. A herbal feed additive was selected based on the consideration that it contained a high diversity of (a) plant species (n = 27; belonging to 10 different plant families), (b) plant parts (herbs and leaves, flowers, seeds, bark and roots) and (c) a wide range of phytochemicals (such as essential oils, tannins and flavonoids). The herbs contained in the feed additive were selected to counterbalance the low phytochemical diversity of current dairy cow diets. We hypothesized positive effects on milk performance traits, fertility, lameness, development of body condition, milk acetone concentrations during early lactation, somatic cell counts and disease-related culling rates.

2 ANIMALS, MATERIAL AND METHODS

A placebo-controlled two-stage on-farm trial was conducted to evaluate the effects of a herbal feed additive (HFA) on health, fertility and milk performance traits of dairy cows. No heifers participated in the studies.

The farmers gave the feed additive once per day to individual cows with a bowl, either in the feed fence or in the milking parlour. Farmers recorded daily whether intake was complete or not. All cows with intake less than 65% of the individual doses within one lactation third (days 1–100, 101–200 and 201–300) were excluded from the analysis.

2.1 Dose-finding study

In a dose-finding study (DF), placebo (PL) was compared to two dosages of HFA (HFA-50 and HFA-100). Eleven farms (six in Germany and five in Switzerland) participated in the DF. Six farms were conventional, and five were managed according to organic standards. Average yield of lactation milk per herd ranged from 5,000 to 10,000 kg, with herd sizes between 35 and 80 cows. Breeds involved were as follows: Holstein (five herds), Swiss Fleckvieh (four herds), German Fleckvieh (one herd) and Brown Swiss (one herd).

A total of 81 cows, calving between 22 November 2010 and 11 March 2011, were stratified (predicted calving date within farm) and randomly assigned to HFA-100, HFA-50 and PL. Six or nine cows (2 or 3 “triplets”) per farm participated in DF. Nineteen cows (HFA-100: 9; HFA-50: 7; PL: 3) were excluded from the analysis due to too low intake of the feed additive, leaving 62 cows for analysis.

The high-dose HFA group (HFA-100) received pure HFA, whereas the feed additive in the low-dose HFA group (HFA-50) contained 50% HFA and 50% PL. Each cow received 100 g of HFA-100, HFA-50 or PL per day, respectively, from 14 days before predicted calving until the 300th lactation day or, in the event of shorter lactation, until the end of lactation.

2.2 Field trial

Based on the results of the DF, HFA-100 was compared to PL in the Field trial (FT). The FT was conducted on 30 farms (15 each in Germany and Switzerland). Of these, 21 were conventional, and nine were managed according to organic standards. Average lactation milk yield per herd ranged from 5,000 to 9,000 kg. Herd size was between 20 and 140 cows of Holstein (16 herds of which one also kept the rare German breed Vorderwälder), Swiss Fleckvieh (6 herds), Brown Swiss (5 herds), German Fleckvieh (2 herds) and mixed breeds (one herd keeping Swiss Fleckvieh as well as Brown Swiss, Holstein and several other breeds).

On farms which participated in both the dose-finding study and the field trial, cows that had participated in DF were excluded from FT. In addition, due to overall high culling rates in DF, all cows which were already intended by the farmer before the project start to be culled in the following lactation were excluded from the study.

A total of 314 cows (calving between 21 December 2012 and 22 July 2013) were stratified (predicted calving date within age category [young cows: 2nd and 3rd lactation, elder cows: >3rd lactation] within farm) and randomly assigned to HFA-100 and PL. A total of 157 cow pairs were included, corresponding to 3–7 pairs per farm. Seventeen pairs were rejected from analysis. Of these, 11 pairs were due to a low intake of feed additive by at least one cow of the pair, and six pairs were due to a divergence of calving dates within a cow pair of more than 90 days. Ultimately, 140 cow pairs were included in the analysis.

Due to poor acceptance of pure HFA in some cows, the palatability of the feed additive was improved by adding wheat bran (80 g), maize flour (80 g), molasses (25 g), brewer's yeast (10 g) and sugar (5 g) to 100 g HFA (HFA-100) or to 100 g Pl respectively. Thus, cows received 300 g of the respective feed daily from 14 days before predicted calving until the 300th lactation day or, in the event of shorter lactation, until the end of lactation.

2.3 Measurements and parameters

Both trials were completely non-invasive. All animal handling was based on common agricultural practice, and no animal was displaced from its home farm. The additives used were composed of commercially available, legally approved feedstuff and additives. The study was conducted according to EU Directive 2010/63/EU concerning animal experiments.

2.3.1 Milk performance data

Monthly milk recording data were available from the Swiss and German breeding organizations. Both organizations conducted 11 milk recordings per farm and year. Milk yield, milk protein and fat content, as well as urea of the first eight test-day records of each individual cow post-partum, were included in data analysis.

2.3.2 Milk acetone

During the first 10 weeks of lactation, farmers took weekly foremilk samples of one udder quarter. Samples were frozen on farm, after addition and dilution of bronopol® as preserving agent. The milk samples were analysed for their acetone content by flow injection analysis (AutoAnalyzer 3) at Suisselab AG, Zollikofen, Switzerland. The cut-off point as threshold for (subclinical) ketosis was defined as ≥10 mg/L (Dorn et al., 2016).

2.3.3 Somatic cell score

The first eight test-day records on somatic cell score (SCS) were included in data analysis. The cut-off point as threshold for elevated SCS was defined as ≥3, which equals a somatic cell count of ≥100,000 somatic cells/ml milk.

2.3.4 Body condition score and lameness

Three trained assessors (always the same person per farm) scored the cows regarding body condition and lameness during regular farm visits once in the dry period before starting the experimental feeding (mean days prior to calving: DF 26 ± 18; FT 25 ± 17), and three times during lactation: once in early (mean days in milk [DIM]: DF 73 ± 10; FT 76 ± 11), once in mid (mean DIM: DF 150 ± 13; FT: 159 ± 13) and once in late lactation (mean DIM: DF 254 ± 16; FT 252 ± 14). Body condition was scored with the system described by Isensee et al. (2014) modified by Spengler, Notz, Ivemeyer, and Walkenhorst (2015) (BCS). With regard to lameness cows were assessed according to the WelfareQuality®Consortium (WelfareQuality® 2009), in most cases in standing and in some cases in moving animals. As soon as one lameness indicator was observed, the cow was assessed as “lame,” otherwise as “not lame.”

2.3.5 Calving interval

All cows were observed from the dry period before starting the administration of the feed additive until 500 days post-partum to determine the calving interval. Cows which did not calve again within 500 days were excluded from the analysis and defined as “culled for infertility.” In the event that one cow of a pair was culled (or defined as culled), this pair was excluded from the analysis regarding this variable in FT.

2.3.6 Culling rates

In DF, we only determined the overall culling rate. In FT, farmers were asked for culling reasons. The main reason was culling due to health problems (udder health, claw or metabolic disorders) or infertility (including those cows which did not calve again within 500 days of post-partum observation). In some cases, the culling reason was not clear or had no connection to the trial, such as age, character, accidents or cows being sold as breeding animal. Therefore, we excluded all pairs with at least one such cow from analysis regarding this variable.

2.4 Feed additives

The commercial feed additive “Dr. Schaette Kräuterkraft Laktation” (SaluVet GmbH, Bad Waldsee, Germany) was used, consisting of 90 g herbs and 10 g of approved feedstuffs for technical reasons (wheat bran and soy oil) per 100 g. The herbal component is a mixture of 27 different plants (Appendix S1), whereby Foeniculum vulgare (L.) MILL. (fructus), Pimpinella anisum L. (fructus), Silybum marianum (L.) GAERTN. (fructus), Trigonella foenum-graecum L. (semen) and Urtica dioica L. (herba) make up for over 50% (w/w) of the herbs. Green meal produced from a multiannual grass–clover mixture was used as placebo (PL) in both trials.

2.4.1 Analysis of feed additive composition

Two consecutive freshly produced batches of HFA and PL (HFA I, HFA II, PL I, PL II) and a retention sample from 2010 (stored dark, cool and dry in a tight glass jar; HFA III, PL III) were analysed in 2018 with regard to proximate components and phytochemicals, selected essential oils and tannins. Only HFA-100 and PL were analysed, since HFA-50 was a mix of HFA-100 and PL.

Proximate components

For determination of crude protein, fibre, neutral detergent fibre (NDF), acid detergent fibre (ADF) and ash content in the feed additive samples, near-infrared spectroscopy was used (calibrated for Swiss herb rich forages; NIRFlex N-500; Büchi).

Essential oils

Approximately 50 g of powdered plant material was placed in a 500 ml round bottom flask, and 200 ml distilled water and boiling beads were added. The flask was attached to a distillation apparatus, with a water bath at approximately 90°C. The mixture was left to distil for 4 hr. The resulting essential oil was collected, and anhydrous sodium sulphate was added to absorb excess water. The oil was analysed on a gas chromatograph (GC 6890N) connected to mass spectrometer detector (MSD 5973N) with a standard electron impact source (all Agilent). Separation was carried out on a DB-5ms column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm, with 10 m integrated guard column, Restek); injection volume was 1 µl; inlet liner: 4 mm splitter (split, 1:15, Restek); inlet temperature 250°C; carrier gas He, at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Equilibration time: 0.25 min, oven programme: 50°C for 1 min, 10°C/min to 290°C, hold 3 min. Solvent delay was 3.00 min. MSD transfer line was set at 280°C, and MS source was 230°C; scanning range from m/z 50 to 500. Chromatograms were integrated and analysed with the NIST Mass Spectral Library (1998). Only hits with a ≥95% match were considered.

Tannins

2.5 Statistical analysis

Within each farm, all cows involved in the study were kept in the same group, and together with and under the same feeding and housing conditions as the other (not involved) cows of the herd. Under these conditions, the treated cows are both experimental and observational units (Bello et al., 2016). Sample size per variable varied in both trials due to incomplete observations of individual cows (DF) or at least one cow of a pair (FT).

We analysed the effect of the feed additive (“treatment”) on different variables using linear mixed effects models and mixed effects logistic regression models applying the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) in the R environment version 3.2.4 and 3.2.5 (R Core Team, 2016). Post hoc analysis was performed conducting Tukey tests using the lsmeans package (Lenth, 2016).

We performed likelihood ratio tests in order to compare different models and to decide on inclusion or exclusion of predictor variables or interactions.

For data from DF, the final model for the dependent variables of milk yield, milk fat content, milk protein content and urea content included treatment (levels: HFA-100, HFA-50 and PL), time (test days 1–8) and lactation class (young = 2nd and 3rd lactation, elder >3rd lactation) as fixed effects. Cow nested within farm was entered as random effect. Analysis of the same dependent variables was performed with treatment (levels: HFA-100 or PL) and time (test days 1–8) as fixed effects and cow nested within pair and farm as random effects for data from the FT.

The other dependent variables were defined as follows:

For acetone, the proportion of observations with an acetone content of ≥10 mg/L milk from samples taken weekly until the 10th week post-partum (resulting in a possible maximum of ten observations per cow) was used as dependent variable (prop-mac).

For somatic cell score, the proportion of samples with SCS ≥3 from the first up to eighth test-day record result of the current lactation was used as dependent variable (prop-scs).

Lameness was defined as proportion of observation events with lame cows from a maximum of three scoring events realized during lactation (prop-lam).

Analysis of body condition score (BCS) was performed on a binary dependent variable describing the occurrence of at least one BCS change of >0.5 scaling points between the subsequent scoring events (bcs_0.5). The total number of scoring events for BCS was four, whereof the score ante partum was used as baseline regarding the change to the first lactation scoring.

Overall culling was analysed both for DF and FT as a binary dependent variable (bin-cull). Differentiated culling reasons were exclusively analysed for the FT and involved separate evaluations for culling due to udder (cull-udder), fertility (cull-fert), metabolic (cull-meta) and leg–claw problems (cull-lame) respectively.

Models for analysis of all dependent variables from DF with exception of the milk record variables described above included treatment (levels: HFA-100, HFA-50 or PL) and lactation class (young = 2nd and 3rd lactation, elder >3rd lactation) as fixed effects and farm as random effect, whereas models for FT data analysis included treatment (levels: HFA-100 or PL) as fixed effect and pair nested within farm as random effect. Moreover, average milk yield over the whole lactation or from the first 100 days in milk was used as covariate in the models analysing the metabolic traits bcs_0.5 and prop-mac respectively. Inspection of residual plots did not reveal any obvious deviations from homoscedasticity or normality, except for the variable calving interval which was therefore log transformed. Statistical significance was determined at p < .05, with tendency at p < .1. Results in tables are presented as least-square means, standard errors, and the p value of the treatment effect obtained with the lsmeans package (Lenth, 2016). Graphs show the output of pairwise comparisons based on results obtained with the multcomp package (Hothorn, Bretz, Westfall, & Heiberger, 2008) in R.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Composition of feed additive

The analysis of proximate components revealed no considerable differences between HFA and PL (Table 1).

| Sample | Dry matter | Crude protein | Crude fibre | NDF | ADF | Ash |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFA I | 88.7 | 12.9 | 23.6 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 11.4 |

| HFA II | 89.2 | 12.7 | 24.7 | 29.6 | 30.6 | 11.2 |

| HFA III | 88.9 | 13.6 | 27.1 | 26.3 | 35.8 | 11.4 |

| PL I | 90.6 | 16.6 | 21.3 | 23.3 | 19.9 | 11.2 |

| PL II | 91.7 | 11.9 | 25.4 | 39.0 | 27.8 | 9.4 |

| PL III | 88.2 | 14.0 | 25.0 | 30.8 | 32.2 | 11.3 |

- Abbreviations: ADF, acid detergent fibre; NDF, neutral detergent fibre.

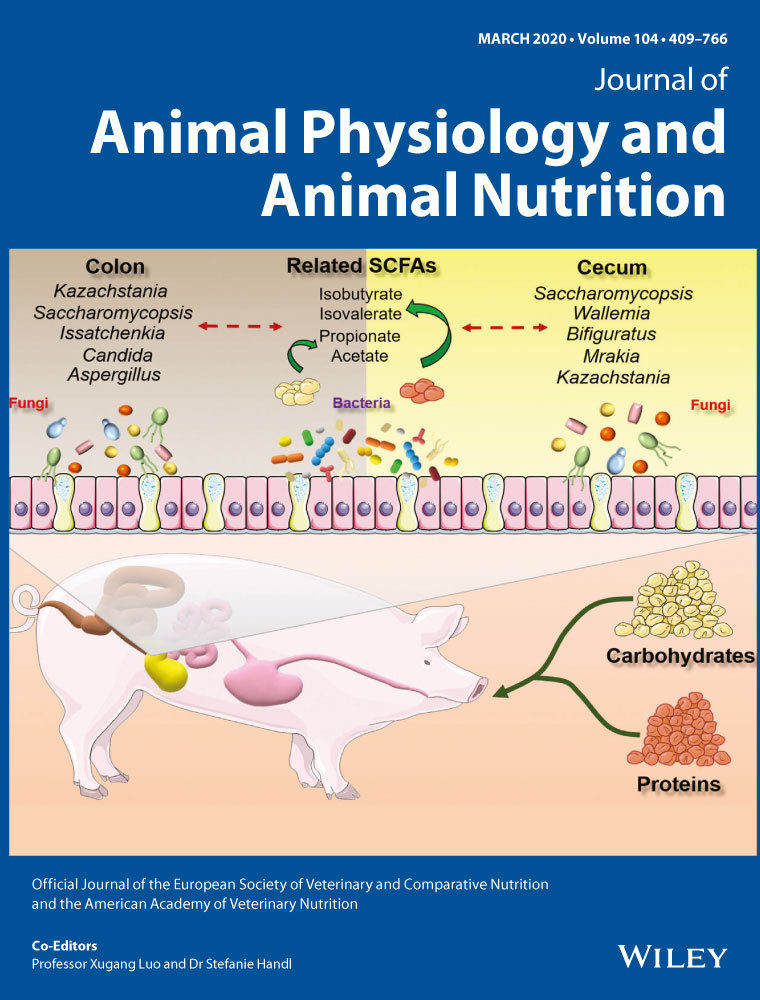

Samples HFA I and HFA II contained approximately 1,000 μl of essential oils, while HFA III afforded around 600 μl, and samples PL I to PL III only gave ≤100 μl of essential oils. Based on the GC-MSD traces, the major volatile compounds contained in the HFA samples were eucalyptol, camphor, estragole and anethole (Figure 1).

While the concentration of non-tannin phenols was somewhat lower in HFA-100 than in PL, total tannin concentration in HFA-100 exceeded PL by approximately 50% (Table 2).

| Sample | Total phenols | Non-tannin phenols | Total tannins |

|---|---|---|---|

| HFA I | 2.73 | 1.28 | 1.45 |

| HFA II | 2.63 | 1.42 | 1.21 |

| HFA III | 2.27 | 1.18 | 1.10 |

| PL I | 2.99 | 2.15 | 0.84 |

| PL II | 2.35 | 1.53 | 0.82 |

| PL III | 2.28 | 1.44 | 0.84 |

3.2 Milk performance data (milk yield, protein content, fat content, urea)

Milk yield, fat content, protein content and urea did not differ between treatments in any of the experiments, except for a tendency towards lower urea content in the HFA-100 treatment compared to PL in DF (p = .06). All other parameters were nearly identical between the treatment groups, both in DF and FT (Table 3).

| DF | FT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFA-100 | HFA-50 | PL | p | HFA-100 | PL | p | |

| n | 128 | 149 | 182 | 894 | 868 | ||

| Daily milk yield (kg) | 27.3 (3.0) | 28.1 (3.0) | 29.9 (2.9) | .26. | 27.2 (1.1) | 27.1 (1.1) | .95 |

| n | 128 | 150 | 182 | 892 | 867 | ||

| Fat content (%) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.1) | .82 | 4.1 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.1) | .47 |

| Protein content (%) | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.1) | 3.2 (0.1) | .82. | 3.3 (0.03) | 3.3 (0.03) | .54 |

| n | 128 | 150 | 182 | 890 | 866 | ||

| Urea content (mg/L) | 21 (2) | 23 (2) | 24 (2) | .08a | 19 (1) | 19 (1) | .70 |

Note

- The results are presented as least-square means (standard errors in brackets), and the p value of the treatment effect (DF, dose-finding study; FT, field trial; HFA, herbal feed additive given as low [50 g/cow × day, HFA-50] or high (100 g/cow × day, HFA-100) dosage; PL, placebo). p value of the F test using Satterthwaite approximation for degrees of freedom.

- a The pairwise comparison of means (Tukey Contrasts) resulted in a difference by tendency between HFA-100 and PL (p = .06); HFA-50 was neither different from PL (p = .7) nor from HFA-100 (p = .3).

3.3 Body condition score

No significant differences between the treatment groups were observed regarding the occurrence of at least one BCS change of ≥0.5 scaling points between two subsequent scoring events (bcs_0.5). In DF, 34% (standard error [SE] 15%) of the cows treated with HFA-100 (n = 16) had at least one BCS change of ≥0.5 scaling points, while 41% (SE 15%) of the cows treated with HFA-50 (n = 19), and 45% (SE 14%) of the cows receiving PL (n = 23) exhibited this change (p = .71). By contrast, 32% (SE 5%) and 34% (SE 5%) of the cows exhibited BCS changes in treatment groups HFA-100 (n = 105) and PL (n = 105), respectively, in the FT (p = .84).

3.4 Milk acetone

We analysed the proportion of observations with an acetone content of ≥10 mg/L milk from milk samples taken weekly until the 10th week post-partum (prop-mac). Elevated acetone contents were significantly lower exhibited in cows of the HFA-100 (4%; SE 2%) and HFA-50 (4%; SE 2%) compared to cows of the PL treatment (12%; SE 6%) in DF. No significant differences could be observed for prop-mac in FT (HFA-100:6%—SE 1%; PL: 7%—SE 1%; Figure 2a).

3.5 Somatic cell score

For somatic cell score, we analysed the proportion of samples with SCS ≥3 from the first up to eight test-day record results of the current lactation (prop-scs). Cows exhibited in DF prop-SCS of 40% (SE 6%), 45% (SE 6%) and 55% (SE 6%) in the treatment groups HFA-100, HFA-50 and PL respectively. Only the difference between cows treated with PL and HFA-100 was statistically significant. In the FT, prop-scs was significantly lower in cows treated with HFA-100 (38%, SE 5%) compared to those of the PL treatment (55%, SE 5%; Figure 2b).

3.6 Lameness

We analysed the proportion of observation events with lame cows from a maximum of three scoring events realized during lactation (prop-lam), which in DF was 11% (SE 6%) for cows in HFA-100, 2% (SE 2%) for cows in HFA-50 and 14% (SE 7%) for cows in PL respectively. Results were statistically significant between HFA-50 and PL, but neither confirmed for HFA-50 versus HFA-100 nor for HFA-100 versus PL. In FT, 8% (SE 2%) of the cows treated with HFA-100 and 10% (SE 2%) of those treated with PL were scored as lame, but the difference was not statistically substantiated (Figure 2c).

3.7 Calving intervals

No significant difference regarding calving interval was observed for cows in DF (371 days with HFA-100, SE 12 days; 371 days with HFA-50, SE 12 days; 385 days with PL, SE 10 days, n = 10, 11 and 15 observations respectively). Calving intervals in FT (385 days with HFA-100, SE 7 days; 400 days with PL, SE 7 days, n = 82 for each treatment) were slightly higher than in DF. In both trials the cows of the HFA-100 treatment exhibited a 2 weeks shorter calving interval, which was by tendency confirmed in FT (p = .07).

3.8 Culling reasons

A high overall culling rate (model prediction: 43% with HFA-100, SE 15%; 45% with HFA-50, SE 14%; 35% with PL, SE 13%) without significant differences between the treatment groups was observed in DF. The average culling rate was much lower in FT (19% with HFA-100, SE 5%; PL: 26% with PL, SE 5%) and, again, did not significantly differ between treatment groups. Regarding the different culling reasons in FT, a tendency towards a lower predicted culling rate due to udder health reasons was observed in HFA-100 (0.5%, SE 0.9%) compared to PL (2%, SE 3%; p = .08; Table 4).

| DF | FT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive means | Least-square means (±SE) | Descriptive means | Least-square means (±SE) | |||||||||

| HFA-100 | HFA-50 | PL | HFA-100 | HFA-50 | PL | p | HFA-100 | PL | HFA-100 | PL | p | |

| n | 18 | 20 | 24 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 121 | 121 | 121 | 121 | ||

| Overall (%) | 44 | 45 | 38 | 43 (15) | 45 (15) | 35 (13) | .82 | 21 | 28 | 19 (5) | 26 (5) | .21 |

| Udder disorders (%) | — | — | — | 2.5 | 7.4 | 0.5 (0.9) | 1.9 (2.8) | .08 | ||||

| Fertility disorders (%) | — | — | — | 15.7 | 15.7 | 11.8 (4.3) | 11.8 (4.3) | 1.00 | ||||

| Claws and legs disorders (%) | — | — | — | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 (0.8) | 2.5 (1.4) | .34 | ||||

| Metabolic disorders (%) | — | — | — | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 (1.4) | 2.5 (1.4) | 1.00 | ||||

Note

- Descriptive mean values, least-square means (standard errors in brackets) and the p value of the treatment effect are presented (DF, dose-finding study; FT. field trial; HFA, herbal feed additive given as low (50 g/cow × day, HFA-50) or high (100 g/cow × day, HFA-100) dosage; PL, placebo). Culling reasons have only been recorded in FT.

4 DISCUSSION

A multi-herbal feed additive (HFA) was administered to dairy cows to test the hypothesis that a diet with an increased botanical diversity and, hence, concentration of phytochemicals would exert beneficial effects on parameters linked to metabolism and health. The study period started 14 days before predicted parturition and ended at 300 days of lactation. In part, the assessed parameters showed responses in favour of the hypothesis. In no case did the experimental treatments have adverse impacts.

4.1 Dosage and composition of feed additive

The lower dosage (HFA-50, corresponding to 45 g herbs per cow and day) was chosen based on producer's recommendations. Interestingly, dosages of 20–50 g herbs per cow and day are also common in historical veterinary pharmacological (Fröhner, 1900) and recent veterinary herbal medicinal (Brendieck-Worm & Melzig, 2018; Reichling et al., 2016) textbooks as well as in current European ethnoveterinary literature sources (Mertenat et al., 2019; Stucki et al., 2019). Furthermore, a study using a comparable herbal feed additive from the same producer found positive effects on culling rates with dosages of 30–60 g per cow and day adjusted to milk performance (Spranger, 1989). In view of the reduced proportion of phytochemicals in modern dairy cows' rations combined with increased performance and feed intake, we also tested a higher dosage (HFA-100, corresponding to 90 g herbs per cow and day).

Most herbs of the mixture are well known from European ethnoveterinary research (Mayer et al., 2014, 2017; Stucki et al., 2019; Vogl et al., 2016). They have been described as orally administered for preventive purposes, such as “general strengthening” (Disler et al., 2014; Mayer et al., 2017; Stucki et al., 2019) or as “healthy feed” (Vogl et al., 2016), or for therapeutic reasons, in particular for gastrointestinal or metabolic disorders (Disler et al., 2014; Mayer et al., 2014, 2017; Stucki et al., 2019).

With 27 different herbal components from plants belonging to 10 different plant families, the HFA is too complex for a discussion of each individual herb (Ayrle et al., 2016). Thus, only the major components of the herbal feed additive are briefly addressed. In recent ethnoveterinary studies (Bischoff et al., 2016; Disler et al., 2014; Stucki et al., 2019), common nettle (Urtica dioica L.) was the most frequently reported herbal drug for “general strengthening.” Flavonoid glycosides and caffeic acid esters seem responsible for its anti-inflammatory and diuretic effect (ESCOP, 2018). The relevant properties of nettle are most likely antimicrobial and antioxidative effects (Kregiel, Pawlikowska, & Antonak, 2018), which are of relevance for udder health. Milk thistle seeds (Silybum marianum L. GAERTNER) and, in particular, their flavanolignans, possess hepatoprotective properties (ESCOP, 2009; Saller, Melzer, Reichling, Brignoli, & Meier, 2007) which might induce positive effects, as the liver is to some degree “causal and contributing to metabolic and related disorders (e.g., fatty liver, ketosis, metritis, lameness)” (van Dorland and Bruckmaier, 2013). Fenugreek seeds (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) are rich in saponins and mucilaginous polysaccharides and possess appetite stimulating properties (ESCOP, 2003) and a rather high antioxidative capacity (El-Tarabany, Teama, Atta, & El-Tarabany, 2018).

The relatively high tannin concentration in HFA-100 was likely due to herbs such as Alchillea millefolium (Fraisse et al., 2007; Jayanegara et al., 2011), Artemisia absinthium (Msaada et al., 2015), Cichorium intybus (Kälber, Meier, Kreuzer, & Leiber, 2011) and Urtica dioica (Kregiel et al., 2018).

As a result of components like thyme, rosemary, oregano, anise, fennel (Blaschek, 2016) and wormwood (Msaada et al., 2015; Nguyen, Tavaszi Sárosi, Llorens-Molina, Ladányi, & Zámborine-Németh, 2018), the daily dosage of HFA-100 contained approximately 2 ml of essential oils, which is comparable to other short and medium term in vivo studies, where effects on metabolism and performance of cows have been found (Khiaosa-ard & Zebeli, 2013).

The above-mentioned potential effects of the main HFA herbs on cattle metabolism and health gave reason to expect an impact of the HFA on performance, and on traits related to the metabolism and health of the cows included in the current study.

4.2 Milk yields and composition

No significant differences could be observed between HFA-100 and PL with regard to milk yields and main solids concentrations. This is in agreement with an earlier study using a comparable HFA (Spranger, 1989), and with some studies investigating the effects of diets rich in tannins (Broderick, Grabber, Muck, & Hymes-Fecht, 2017; Kälber et al., 2011). However, the impact of tannin-rich feed on the protein metabolism of ruminants, leading to higher protein and lower urea concentrations in milk, has been shown recently (Broderick, 2018; Girard et al., 2016; Gulinski, Salamończyk, & Mlynek, 2016). In DF, milk urea was slightly lower in the HFA-100 group, but the effect was not statistically significant (Table 3). Previous reports about the influence of essential oils on milk yields and composition have been inconsistent (Braun, Schrapers, Mahlkow-Nerge, Stumpff, & Rosendahl, 2018; Silva et al., 2018).

4.3 Body condition and energy metabolism

Tannins in feeds may influence ruminal protein metabolism and reduce ammonia production (Jayanegara, Marquardt, Wina, Kreuzer, & Leiber, 2013). This would decrease the metabolic burden of the liver (Parker, Lomax, Seal, & Wilton, 1995) and improve availability of endogenous energy, leading to beneficial effects of HFA on indicators of the energy household of early lactating cows.

Body condition score development is an important indicator of mobilization and, thus, energy metabolism and ketosis risk in cows (Isensee et al., 2014). Diets rich in tannins and other phytochemicals like essential oils may have a positive effect on body weight and body condition (Broderick et al., 2017; Silva et al., 2018; Tedesco et al., 2004; Ulger, Onmaz, & Ayasan, 2017). In contrast, no effect of HFA on BCS was observed in the current study.

Ketone bodies in blood or milk are another indicator of fat mobilization and ketosis risk. We found inconsistent results with regard to milk acetone during early lactation as a criterion of metabolic health. In DF, a significantly lower number of milk samples with elevated acetone levels were seen with HFA-50 and HFA-100 compared to placebo. In an earlier study, a phytogenic feed additive containing sodium propionate caused a slight but significant reduction in milk acetone in the treatment of subclinical ketosis of early lactating dairy cows compared to treatment with pure sodium propionate or placebo (Dorn et al., 2016). Two (fenugreek and chicory root) of the seven herbs used by Dorn et al. (2016) are also components of HFA. Essential oils might have a positive effect with regard to energy metabolism in early lactation. A recent meta-analysis indicates an increased ruminal propionate production upon oral administration of essential oils (Khiaosa-ard & Zebeli, 2013). Increased propionate production elevates gluconeogenesis in the liver and lowers the risk of ketosis.

In FT, no differences were seen between HFA and PL regarding milk acetone. This might be due to a lower value of elevated milk acetone (prop-mac) in the placebo group in FT compared to DF (7% vs. 12% respectively). Furthermore, the lower occurrence of elevated milk acetone is in accordance with a substantially lower occurrence of at least one BCS change of ≥0.5 scaling points between two subsequent scoring events (bcs_0.5) in the placebo group in FT (34%) compared to the placebo group of DF (45%). It is a fundamental problem with all studies analysing preventive aspects of feed additives that they require relatively high risk in the population for a disease parameter to show any effect. However, in FT the HFA-100 group also exhibited slightly higher values of prop-mac than in DF (DF: 4%, FT: 6%) but a comparable bcs_0.5 (DF: 34%, FT: 32%). In a recent study, a phytogenic feed additive delivered positive effects on energy metabolism of early lactating dairy heifers fed with a soybean-rich diet (Hashemzadeh-Cigari et al., 2015). Interestingly, these positive effects were not due to lower blood β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations (which are well correlated with the milk acetone content, Dorn et al., 2016), but were mainly explained by lower contents of non-esterified fatty acids. As no blood samples were drawn in our study, a comparison is not possible for this parameter.

4.4 Lameness

In DF, lameness in the HFA-50 group was significantly lower than in the placebo group. Although lameness in DF and FT, and the total culling rate for lameness reasons in FT, was lower with HFA-100 compared to PL, these differences were not statistically significant. The inverse dose-dependency remains unclear. Nevertheless, there are some arguments to expect positive effects of the herbal feed additive on claw diseases. It has been demonstrated that diets rich in phytochemicals increase concentrations of functional fatty acid in various tissues of ruminants (Leiber et al., 2019; Willems, Kreuzer, & Leiber, 2014), and this could explain to a certain degree that fatty acid profiles in claws vary (Raber, Scheeder, Ossent, Lischer, & Geyer, 2006). Inflammatory processes are common reasons for lameness (LokeshBabu et al., 2018) and can be modulated by functional long-chain fatty acids and their derivatives (Barcelo-Coblijn & Murphy, 2009). In particular, milk thistle flavanolignans have been found to exhibit direct anti-inflammatory properties in dairy cows' hoof dermal cells (Tian et al., 2019).

4.5 Udder health

Udder health is one of the main concerns and one of the main culling reasons in dairy cow herds (Kerslake et al., 2018). In DF and FT, the HFA-100 group showed approximately 15% less test results with elevated somatic cell counts than the placebo group (DF: 40% with HFA-100 and 55% with PL; FT: 38% with HFA-100 and 55% with PL). In FT, less cows were culled for udder health reasons in the HFA-100 group compared to PL by tendency (p = .08). This result matches the overall better udder health situation in HFA-100 group compared to PL.

Earlier short-term studies already found that plants rich in phytochemicals improved udder health. Oral administration of Asparagus racemosus Willd root powder for 90 days significantly decreased SCC (Kumar, Mehla, Sirohi, Dang, & Kimothi, 2012). A significant decrease of SCC in cows with elevated SCC was observed after administration of a herbal feed additive for 24 days (Hashemzadeh-Cigari et al., 2014).

Some phytochemicals in HFA may possess antimicrobial activity against udder pathogens (Fratini et al., 2014; Kregiel et al., 2018). However, it is unlikely that minimal inhibitory concentrations of essential oils or other phytochemicals in the udder tissue or in the milk could be reached by oral application of HFA. Stimulation of the immune system and antioxidant effects may also play a role. Oral administration of a papaya extract was recently found to upregulate immune- and antioxidant-related gene and protein expression in somatic cells of cow milk (Abouzed et al., 2019). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects are known for the majority of herbs of HFA, at least from in vitro or in vivo studies with rodents (ESCOP, 2003, 2009, 2018; Jungbauer & Medjakovic, 2012). Recent in vitro (Perruchot et al., 2019) and in vivo (Oloagaray et al., 2019) studies showed positive effects of an extract of Scutellaria baicalensis GEORGI on bovine mammary cells and udder health. The authors traced the measured effects back to flavonoids of high antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties. In the “highly complex nature of mammary gland immunology” (Sordilllo, 2018), these properties may play an important role in reducing the SCC. On the one hand, antioxidants protect immune cells from oxidative stress, making them more successful in eliminating pathogens (Sordilllo, 2018) and thus leading to lower SCC. On the other hand, it is known from recent studies that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are able to reduce SCC during and after acute or induced mastitis (Dan, Bruckmaier, & Wellnitz, 2018; McDougall, Bryan, & Tiddy, 2009). These findings may indicate that overshooting immune reactions of the mammary gland could be counterproductive for the restorative process of the mammary gland after an inflammatory process. The anti-inflammatory properties of herbs — which are well known and of a more diverse mode of action than NSAID — may be helpful in this context.

The true reason for the udder health improving effect of HFA could be based on the well-known and above-mentioned “multi-target drug” character of plants rich in phytochemicals (Saller et al., 2007) — alone or, even more so, in herbal combinations. However, this remains speculative and further udder health-focused studies with herbal additives are required to clarify the mode(s) of action.

4.6 Overall culling rate

Neither in DF nor in FT were significant differences determined between HFA-100 (DF: 43%, FT: 19%) and PL (DF: 35%, FT: 26%) with regard to overall culling rates. This is in contrast to an earlier study with a feed additive similar to HFA (Spranger, 1989) where the herbal feed additive group showed significantly lower overall yearly culling rates (16%) compared to placebo (24%). Nevertheless, the overall culling rates of FT correspond to European overall culling rates in dairy cows (Nor, Steeneveld, & Hogeveen, 2014). Results on culling rates and reason have to be interpreted with caution in view of limited sample size, especially in DF, low proportions of the variance explained by the model used to detect treatment effects, and high standard errors of the mean especially for culling reasons with low incidence.

4.7 Fertility

In FT, the culling rate for fertility reasons was identical (11.8%) in the HFA-100 and PL group. Infertility is among the most common culling reasons in dairy cows (Ahlman, Berglund, Rydhmer, & Strandberg, 2011). In DF and in FT, the calving interval of cows of the HFA-100 group was about 2 weeks shorter than in the PL group, but was confirmed only by tendency (p = .07) in FT. Overall, the calving intervals were comparable to data from other European studies (Leiber et al., 2017). Recently, oral application of Chinese herbs has been found to have positive effects on fertility (Cui et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2018).

5 CONCLUSION

In a placebo-controlled study, the daily administration of 100 g of a multicomponent herbal feed additive from 14 days before predicted calving to the 300th day of lactation led to udder health improvement. We found some evidence of reduced milk acetone in early lactation, shorter calving intervals and less culling due to udder diseases. In none of the measured health and performance parameters the herbal feed additive resulted in significant negative effects nor in any tendency towards such effects. The overall effects observed were certainly multifactorial given the composition of the herbal feed additive and, hence, its phytochemical complexity. However, the results further support the beneficial effects of a botanically and thereby phytochemically rich diet for dairy cows.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to all participating farmers for their dedication and perseverance in this long-term study. They applied two to three different feed additives individually in 6–21 dairy cows of their herds once a day for more than 300 days each and over a time span of more than 3 years. We thank Hannah Ayrle for the support during the field trial and Kurt Riedi for designing the figures (both Research Institute of Organic Agriculture, FiBL).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The study was funded by SaluVet GmbH, Bad Waldsee, Germany. The funding institution was neither involved in data collection nor in data analysis. Two of the authors are staff of SaluVet GmbH.

ANIMAL WELFARE STATEMENT

Both trials were completely non-invasive. All animal handling was based on common agricultural practice, and no animal was displaced from its home farm. The additives used were composed of commercially available, legally approved feedstuff and additives. The study was conducted according to EU Directive 2010/63/EU concerning animal experiments.