Demonstration of payer readiness for value-based care in a fee-for-service environment: Measuring provider performance on sealant delivery

Abstract

Objectives

Previously published sealant measures are not useful when applied to Medicaid claims data in states where dental services are carved out of managed care. A novel sealant measure was developed to assess the degree to which dental providers seal eligible teeth during preventive dental visits (PDVs) in an effort to ascertain if such a measure can be used to valuate provider performance, as condition of potential value-based care model implementation.

Methods

A single-county feasibility study was conducted using Medicaid claims. A study cohort included children aged 8 years and enrolled 12 months during 2018. Prospective analysis was used to determine whether dental sealants were applied by the same dentists during PDVs or up to 9 months thereafter. Eligible teeth included first permanent molars. Teeth previously restored, sealed or missing were excluded. PDV was defined as any encounter with prophylaxis, fluoride treatment, or EPSDT. Claims were compared to public health surveillance for measurement validation.

Results

Single-county results showed 11 percent of eligible teeth were sealed. Only 9 percent of dentists applied sealants to at least 40 percent of eligible teeth. Face validation of sealant rate was 23 percent Medicaid versus 36 percent Public Health. The former measures incidence and the latter prevalence with greater heterogeneity that included partially retained sealants.

Conclusions

A sealant measure that assesses provider adherence to sealant standards of care was produced. It has potential application for assessing performance of pediatric preventive services and informing value-based performance expectations.

Introduction

Measurement of value-based care (VBC) for oral health has focused on assessing its impact on patient outcomes.1 Available frameworks and readiness concepts for VBC participation included measures at both patient and population-levels and were intended for health-care providers and health systems.2 Patient outcomes are the ultimate evidence that a health system effectively espouses VBC characteristics. There is, however, a measurement chasm in dentistry linking provider performance to patient outcomes. Many state Medicaid programs continue to operate dental programs as fee-for-service. If those programs wish to implement VBC models for dental services, then it is essential they be able to measure provider performance as that is the only unit of change that can be influenced in the fee-for-service model. As will be demonstrated in this current paper, South Carolina began exploring patient and population outcomes that might serve as reasonable proxies of value in dental care delivery for children. One outcome explored was receipt of dental sealants, primarily because it a) has established standards of care, b) potentially generates cost savings, and c) can be measured at patient and population-levels with administrative claims data.

The clinical and cost-effectiveness of dental sealants as caries prevention agents have been well documented.3-5 Clinical guidelines jointly published by the American Dental Association and the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry6 describe how dental teams should include dental sealants as part of their comprehensive caries management plans for pediatric patients. Their recommendations resonate more profoundly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic which necessitates dentistry engage in aerolsolizing care as a last resort. Dental sealants potentially disrupt caries development pathways, reducing the risk for needing treatment modalities that conflict with current public health states of emergencies.

The Dental Quality Alliance (DQA) has provided national leadership in promulgating quality measures for dentistry, including the use of dental sealants.7 The unit of measure from the DQA sealant quality indicator has historically been at the child-level, operationalized as percentages of pediatric cohorts receiving dental sealants.8 The ability to assess such measures using claims data is essential for state Medicaid programs wishing to implement value-based care models in their dental programs. There have been inconsistencies in the validation of DQA sealant measures, and others similarly designed with claims data. When assessing such measures, correlations between claims and dental records data have been observed.9 However, recent studies have shown these national measures do not account for patients for whom sealants are not an option due to previous restorations, sealants, or noneruption.10, 11

In addition to validation inconsistencies, there is some question as to whether a patient-level measure reflects a quality construct. Literally defined by the Institute of Medicine, quality is “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge” (IOM, 1990, p. 21).12 Rules of grammar suggest the patient, in the IOM definition, is the indirect object and may not be the appropriate unit of measure for sealant quality. Additionally, there are considerable social determinants of oral health13 that potentially confound patient-focused sealant quality measures. Addressing social determinants are important clinically but most are beyond the influence of dental clinicians and insurance providers like Medicaid. To incorporate quality measures contingent on patient engagement and social factors potentially (and unjustly) penalized providers in a value-based care reimbursement environment.

With the aforementioned considerations, we wish to reframe the discussion over sealant quality. As fee-for-service Medicaid dental programs explore value-based reimbursement, provider performance, not quality should be the focus. In that spirit, and using the IHI definition of quality, we demonstrated how Medicaid programs might use their own claims data to assess provider performance as a condition of potential VBC payments. The novel provider performance measure (NPPM) centers on dental providers' compliance with a standard of care, not whether patients received dental sealants. The NPPM assesses the degree to which dental providers seal eligible teeth in conjunction with preventive dental visits (PDVs) in an effort to ascertain if such a measure can be used to valuate performance that might be conditional for VBC payment.

Methods

As state Medicaid dental programs explored the use of sealant quality measures as condition for VBC implementation, the opportunity emerged in South Carolina to develop a different measure that was more appropriate for its fee-for-service environment. Three assumptions were used to frame the NPPM. Drawing from previously published efforts, those assumptions pertained to: a) data concerns, b) systematic control for social determinants of health, and c) definition of quality. The first assumption was that the measure should be assessed using Medicaid claims data given its general accessibility, affordability, and consistency in format. It would be difficult for the agency to rely on data external to the program for decision-making purposes. The measurement of extraneous influences such as social determinants of health, enrollment eligibility criteria and health plan policies may impact service utilization patterns. These factors are beyond the influence of dental providers and should therefore not be considered in any payment-related algorithm. The third assumption asserted quality measurement equates to assessing a provider's adherence to a standard of care, again adopting the IHI approach to valuating quality. As a result of these assumptions, the NPPM proposed, “When presented with the opportunity to seal an eligible tooth, did the dental provider deliver services in keeping with the clinical standard of care during a PDV?”

Single-county feasibility assessment

The demonstration of the new measure employed a single county analysis. Its purpose was to determine the feasibility of the NPPM. Charleston County was selected as the “test” county for statistical reasons. It was home to the most dentists (n = 431) and the second lowest population-to-dentist ratio (940:1) than any other South Carolina County in 2018.14 It was also the third most populated county in the state (n = 405,905)15 with the second largest population of children under age 18 (n = 79,933).16 Combined, these statistics suggested there would be sufficient opportunity to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed measure.

Operationalizing the NPPM

The four essential components operationalized for the analysis of the proposed measure were dentist, service, child and tooth. Given the new measure centered on provider performance, identifying a cohort of dentists was the first step. The rendering National Provider Identifier (NPI) was used to ensure dentists were not duplicated due to the possibility of being categorized under more than one specialty, such as general and pediatric, in the Medicaid program. General and pediatric dentists were limited to the study cohort because they were the most likely to provide PDVs and dental sealants. In cases where an NPI was associated with both specialty types, the highest specialty training was assigned the NPI. Unique NPIs were then encrypted so individual dentists could not be identified. Once the dentist cohort was created, PDVs were defined as encounters that included prophylaxis, fluoride treatment, or an Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) visits.

The third component to the NPPM was identifying eligible teeth, which was only possible through a patient cohort. It was defined as children aged 8 years at any point in time during state fiscal year (SFY) 2018 (July 1, 2017 through June 30, 2018. They also had to be continuously enrolled in Medicaid for all 12 months of the study period, as well as the preceding 4 years in order to determine tooth eligibility. Age 8 was chosen to maximize the availability of fully erupted molars, given eruption usually occurs between ages 6 and 7 years.17 Eligible teeth from the patient cohort were first permanent molars: 3, 14, 19, and 30. Teeth previously restored filled, sealed or missing were excluded from the analysis, as defined by codes in the D2000 and D3000 ranges as well as D7000 – D7251. CDT procedure code D1354 (application of caries arresting medicament) was not included in the exclusion criteria because it was not a covered service during the study period. A 4-year retrospective analysis (to fourth birthday) of the study cohort was conducted to determine tooth eligibility. Table 1 summarizes the data dictionary for the variables that were used from South Carolina claims data.

| Variables | SC Medicaid claims data codes | Total number of unduplicated observations |

|---|---|---|

| Dentist Information | ||

| Rendering NPI | x001_line_npi | 75 (encrypted) |

| Specialty type – General or Pediatric | orig_line_specialty = ‘00’ (GD) or ‘43’ (Pedo) | ‘00’ (GD) = 63‘43’ (Pedo) = 12 |

| Child Information (8 years of age with 12 months of enrollment) | ||

| Enrollment date | month from July 01, 2017 to June 30, 2018 | Not applicable |

| Age | 8 (calculated on date of service) | 1894 |

| Eligible teeth | ||

| 3 | tooth_no = ‘3’ | 1,031 |

| 14 | tooth_no = ‘14’ | 1,055 |

| 19 | tooth_no = ‘19’ | 1,013 |

| 30 | tooth_no = ‘30’ | 1,013 |

| Preventive dental visits | ||

| Prophylaxis | procedure_code = ‘D1120’ | 2057 |

| Sealants | procedure_code = ‘D1351’ | 469 (on eligible teeth) |

| EPSDT | procedure_code =‘D0120’ or ‘D0145’ or ‘D0150’ | 2,135 |

| Fluoride treatment | procedure_code = ‘1206' or ‘D1208’ | 2029 |

| Service date | date_of_service | |

| County of service | prov_county | 46 individual counties |

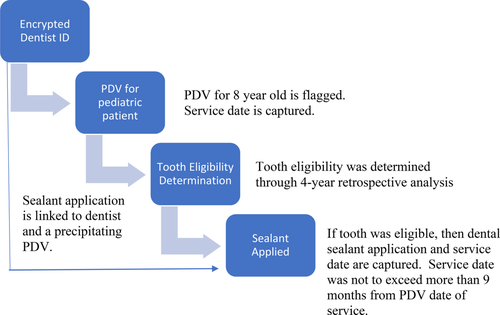

Figure 1 delineates how a unique encounter was configured to assess the measure. Dentists with claims for PDVs with children aged 8 years in state fiscal year 2018 were flagged. Sealant eligibility for individual permanent molars was determined for each child at the time of a PDV. If there was no evidence of sealant placement on eligible teeth at the time of a PDV, a prospective examination of the data up to 9-months after the PDV was conducted. This would ensure maximum sealant performance “credit” would be given to the provider. Accounting for a deferment period between a PDV and sealant placement was necessary, due to the potential clinical, behavioral, or scheduling reasons for delaying sealant applications during a PDV.18, 19 In cases where children saw more than one dentist for a PDV, their eligible teeth were counted under each dentist seen in the study period. In the event a child had more than one PDV to the same dentist in the same year, his or her eligible teeth were counted on the last PDV of the fiscal year.

An exercise in face validity determination

Given the measure was by definition novel, we assessed for preliminary face validity,20 based on the informed judgments of content experts.21 Fortuitously, the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (SCDHEC), Division of Oral Health had completed a statewide oral health needs assessment (OHNA) during the same time period. Public health agencies such as SCDHEC use the Basic Screening Survey22 to conduct the OHNA. Developed by the Association of State and Territorial Dental Directors, the Basic Screening Survey includes a prevalence measure of sealants among children in the third grade. We conducted a telephone interview with the State Public Health Dental Director who provided unpublished sealant prevalence measures for Charleston County children who made up a convenience sample for the OHNA. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4.23 The study was approved as exempt research by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Results

The feasibility study cohort consisted of 75 unduplicated dentists who provided PDVs to 1,894 children aged 8 years with 12 months of Medicaid enrollment for Charleston County for SFY 2018. The majority (89 percent) of the children had 12 months of enrollment in the fiscal year. Among these children, 7,576 unduplicated teeth numbered 3, 14, 19, and 30 were found in the claims data. More than half (54.3 percent, n = 4,112) were identified as eligible (no previous restorations, sealants or extractions) and 45.7 percent (n = 3,464) were ineligible. Interestingly, 42.3 percent and 46.0 percent of teeth were ineligible by ages 6 and 7 years, respectively. Assuming each of the1,894 children had four teeth, there should have been a total of 7,576 permanent molars found.

Only 11.4 percent (n = 469) of the 4,112 eligible teeth were sealed during or after a PDV among 23.3 percent of the children seen in SFY 2018. When sealants were applied to eligible teeth, 51.0 percent (n = 239) of sealants, were applied the same days of PDVs. The majority (81 percent) of sealants were applied within 3 months, 85 percent within 6 months and 97 percent within 9 months. We assert reasonable face validity based on preliminary, unpublished public health surveillance data for Charleston County that reported a sealant prevalence rate of 36 percent. The NPPM assesses incidence for Charleston County residents aged 8 years old with 12 months of continuous Medicaid enrollment. The OHNA reflected a convenience sample of third grade students enrolled in six public schools, of varying ages, household incomes, and insurance statuses. While they are noncomparison groups, the range was acceptable for the study to proceed with validity assurances.

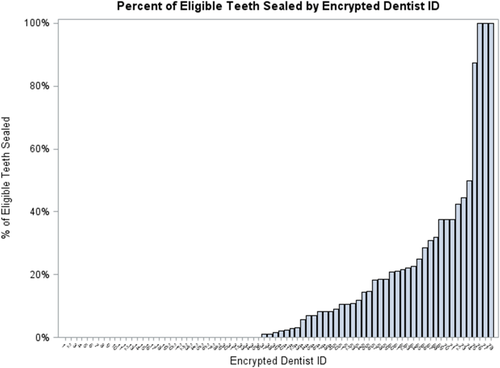

At the individual dentist-level, the NPPM remained unchanged. Table 2 delineates a distribution and variance of the percent of eligible teeth sealed by each dentist in the feasibility phase. Each dentist provided PDVs to more than 25 children and had the opportunity to seal nearly 55 teeth. Unfortunately, each dentist sealed on average six teeth, an average sealant application rate of 14 percent. The descriptive analysis demonstrated that only 9 percent of Charleston County dentists sealed greater than 40 percent of eligible teeth when children presented for care. Figure 2 demonstrates a skewed distribution of dentists and their sealant applications provided during the feasibility study. Based on these descriptive results, the NPPM was nuanced to ask, “what percentage of dentists sealed at least 50 percent of eligible teeth during or in connection with PDVs?”

| Variable | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of children with PDV | 25.8 | 8.0 | 47.0 | 1.0 | 265.0 |

| Number of eligible teeth | 54.9 | 17.5 | 105.0 | 0 | 667.0 |

| Number of eligible teeth sealed | 6.0 | 1.5 | 14.8 | 0 | 86.0 |

| Percent of eligible teeth sealed | 14% | 2% | 23% | 0% | 100% |

Discussion

Summary of findings

The current study successfully demonstrated a novel approach to measuring provider performance, a conditional requirement for VBC model implementation in a Medicaid fee-for-service environment. The methodology shifts measurement from prevalence among children, as in national quality measures, to dentists' performance on a standard of care. The NPPM adopted elements of similar studies previously described8-11 but isolates dentist's performance as an operationalized measure, a prerequisite for exploring alternative payment models that are linked to care value and clinical performance.

Limitations

While we are confident in the potential use of the NPPM for sealants in a VBC environment, there are a number of limitations in its utility. The NPPM only measures a dentist's compliance with a standard of care, that is, placement of sealants on eligible teeth as a part of a PDV. It does not assess the quality of the sealant placement, nor does it account for sealant retention.

The second limitation, and most difficult to overcome, is patients' caries risk levels were not accounted for in the measure. Caries risk levels (D0601, D0602, and D0603)24 were missing from the claims data because they were not a requirement for reimbursement. South Carolina's Medicaid program does not require a common risk assessment tool. Poor evidence of risk assessment tool validation25 creates administrative challenges for Medicaid programs as they explore how to link caries risk, care plans, and value-based reimbursement. While we understand there may be some children with tooth morphology that make sealants counterindicated, in a Medicaid population, it is likely an underrepresented group. The purpose of this article is not to argue the merits of universal sealants but to demonstrate a methodology for assisting payers in measuring provider performance against a standard of care as condition for VBC participation.

The third limitation was our inability to account for eligible teeth at PDVs that did not get sealed due to need for restorative care. It is possible caries diagnoses were made during PDVs and treatment plans called for restorations of eligible teeth at subsequent visits, rather than sealing them. The limitation is twofold in that restorative services could not be linked to previous PDVs because dentistry uses procedure-based billing. If diagnostic-based billing had been used, a link between diagnoses during PDVs and subsequent restorative care during would have improved the analysis.

Lastly, the data are limited in its ability to inform why there were lengthy delays between PDVs and some sealant applications. Not included in the scope of the current analysis was the use of sedation for behavioral management during sealant placements. This, along with a myriad of other reasons previously described could account for reasons why dentists would have not applied sealants the same day as PDVs.

Value propositions

The US health-care system is undergoing a transformation as alternative payment models tied to quality and value become more prevalent and in fact, are required. By 2025, Medicaid programs are targeting 50 percent of all payments use alternative payment models.26 This expectation includes states that continue to administer their dental benefits as fee-for-service (FFS). As such, quality measures such as the NPPM described in the current study is essential. In a VBC model, quality should be equated to provider performance rather than assigned to prevalence of patient outcomes or risk, which can be confounded by social determinants.

So how can dental practices be supported or incentivized to improve sealant application rates, especially for same day PDV applications? The National Network for Oral Health Access has led the way in improving sealant rates for its member community health center dental programs.27 The NNOHA Sealant Collaborative is based on quality improvement strategies and frameworks not unique to community health centers. NNOHA encourages same day sealants during PDVs and coaches their members on how to achieve that goal through quality improvement approaches. The same principles translate to private practices and can be used to frame value-based reimbursement models for Medicaid programs, even in states that operate in FFS environments. In the case of sealants, alternative payments could be structured to incentivize same day applications with regular payments made to dentists if they have to be delayed. Bundling sealant payments with oral examinations and risk assessments could be the first phase of demonstration for financially incentivizing sealants. NNOHA also encourages its members to rely on metrics and data to drive change. Dental practices long since mastered the art of scheduling routine visits with varying scopes of service. Patients who are due X-rays as a part of routine visits are given more time on the schedule than those who do not. In the same way, practices use information from practice management software to build out their schedules for X-rays, they can also accommodate risk-based sealants.

Caries risk should be accounted for in alternative or value-based care reimbursement models so as to establish performance expectations but also avoid unfairly penalizing dentists who attempt to comply with the standard of care. There is an inherent flaw in this approach as no caries risk assessment tool has been validated to the satisfaction of organized dentistry or the dental research community. This is indeed an area worthy of further research. Inherent to risk assessment is the need for diagnostic-based billing. In 2016, a conference convening, “Toward a Diagnosis-Driven Profession,”28 was held of members from the American Dental Association, American Association of Dental Research and the International Association of Dental Research. This meeting generated a series of recommendations for the profession to move the profession from procedure-based billing to reimbursement models driven by diagnoses and treatment informed by diagnoses. The attendees communicated the principle drivers for facilitating these changes include a) governmental mandates from payers such as Medicaid, b) financial incentives either through improved reimbursements or penalties, c) facilitative electronic health records, and d) education among providers on the value of diagnosis-driven treatment planning and billing. Imagine a list of diagnoses, such as the presence of Streptococcus mutans, programmed in EHRs that would trigger a dentist to include sealants in personalized, risk-based caries management plans. From a quality measurement, and ultimately a value-based reimbursement perspective, such a policy configuration would allow payors like Medicaid to assess, with greater sensitivity, the degree to which dentists are providing evidence and risk-based care.

Conclusion

The current study sheds light on the feasibility and appropriateness of assessing sealant delivery based on dentist performance, not prevalence rates among children. The operationalization of this type of measure is essential as Medicaid programs develop value-based care reimbursement models. Most Medicaid programs are pursuing new payment methodologies that focus on appropriateness, care variation, and person-centered care for all patients through the dissemination of best practices with the goal of reducing ineffective care and inappropriate utilization of services.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Raymond Lala, the South Carolina State Public Health Dental Director for the Division of Oral Health at SCDHEC. Dr. Lala was instrumental in the determining of face validity by sharing preliminary sealant prevalence estimates for Charleston County.