Resource Dependence and Network Relations: A Test of Venture Capital Investment Termination in China

ABSTRACT

This study examines how venture capital (VC) firms terminate investments in an emerging economy context. We contend that due to the weak institutional environment, it is appropriate to draw on insights from power and social relation perspectives for a better understanding of the phenomenon. Specifically, we argue that a termination decision hinges on not only the dependence relationship between a VC firm and its portfolio companies, but also the social relationships among VC firms. Event history analyses of approximately 12,000 VC deals made in China between 2001 and 2012 reveal that when a VC firm has a greater number of investments in an industry, it is more likely to terminate investments on a portfolio company in that industry. Moreover, such effect on termination is moderated by the focal VC's embeddedness with its syndicate partners and collaboration opportunities with other VC firms outside the immediate access of the syndicate partners. Our study sheds light on research on VC decision making in emerging markets by integrating insights from resource dependence relationships and interorganizational network characteristics.

Introduction

As vital resource suppliers, venture capital (VC) firms nurture entrepreneurship and foster venture growth. Extensive studies have examined how VC firms make investment decisions. Recently, the VC literature has become interested in how VC firms terminate investments and its consequences (Fulghieri and Sevilir, 2009; Jovanovic and Szentes, 2013; Zhelyazkov and Gulati, 2016). After all, termination of an existing investment is a significant decision because it affects not only the financial performance of a VC firm, but also the relationships and future interactions among VC firms. The extant work on VC investment termination primarily focus on how VC firms balance its investment portfolio and make termination decisions based on payoff calculation with a real option or game theory perspective (Hellmann and Thiele, 2015; Li and Chi, 2013). However, almost all VC investment termination studies are built upon VC industries in well-established institutional environments such as the US.

It is commonly believed that emerging economies have weak institutions and volatile institutional environments: information asymmetry is rampant; contracts are weakly enforced, and non-contractual relationships are prevailing and important (Batjargal et al., 2013; Hitt et al., 2004). These unique aspects of emerging economies render those studies built upon established institutions less meaningful (Ahlstrom and Bruton, 2006; Webb et al., 2009). For example, holding up or retaliation may cause serious damage to a VC firm when it decides to replace a founder CEO, a common practice in developed economies (Bottazzi et al., 2008; Kunze, 1991). These institutional differences call for novel perspectives to examine the same phenomena and a renewed research question: why do VC firms terminate their investments in an emerging market context?

Our study adopts and extends the resource dependence perspective to examine VC investment termination in an emerging economy context. In the VC context, there are two types of resource dependence relationships. Vertical dependence refers to the dependence relationship between a focal VC and its portfolio companies. Horizontal dependence refers to the network connections between a VC and other VC firms in two forms. Integrating RDT with social network research (Sorenson and Stuart, 2008), we focus on the deal-dependent VC network and the deal-independent VC network, which are defined in terms of local network embeddedness associated with a focal syndicate and in terms of alternative partnering opportunities outside the focal syndicate, respectively. We contend that vertical and horizontal dependence relationships will jointly influence a VC's decision to terminate an investment. We then develop hypotheses accordingly and test them with event history analyses on approximately 12,000 VC deals in China between 2001 and 2012. Our findings support the hypothesis that decreasing dependence on portfolio companies will increase the propensity to terminate investments. Such relationship is moderated by a VC firm's horizontal dependence with regard to its peer VC firms, either in the deal-dependent network or deal-independent network.

Our study makes several contributions. First, our study expands the theoretical scope of resource dependence studies. Although each type of dependence relationship was addressed before in either resource dependence or social network literature (e.g., Hallen et al., 2014; Rogan and Greve, 2014; Rowley et al., 2005), we integrate both types of dependence relationships in the setting of VC syndicate investments and contend that a holistic consideration of them, especially their interactions, is necessary. Second, our study contributes to the growing literature on VC industries in emerging economies. Despite rising research interest in how VC industries evolves in emerging markets (Ahlstrom and Bruton, 2006; Bruton et al., 2008), few studies adopted a rigorous research design to investigate VC investment termination. Our study therefore adds an important missing piece in understanding how VC firms make decisions in emerging markets. Lastly, our study enriches the entrepreneurship literature in emerging markets which often focuses on the demand side or how entrepreneurs and start-ups acquire critical resources when institutional development is weak and insufficient (e.g., Batjargal et al., 2013; Hitt et al., 2004). We, instead, look from the perspective of the resource suppliers (i.e., VC firms) and examine how these resource-providers make decisions and allocate resources in a weak institutional environment. Our study sheds light on future research that can investigate how resource-providers affect new venture development and how new ventures interact with key resource-providers in emerging markets.

Research Background

A VC firm is a professional firm that makes equity investments in high-risk and high-return companies. A typical VC investment will go through multiple stages from initial investment, follow-up investments, until an exit via an initial public offering (IPO), an acquisition, or a write-off (Gompers and Lerner, 2004). Even VC firms conduct careful due diligence and engage in active management, studies on the U.S. VC industry reveal that as high as 40 percent of VC-invested companies fail eventually (Chemmanur et al., 2011; NVCA, 2012). VC firms often form a syndicate to co-invest in a portfolio company in order to reduce investment risk, share information, and/or pool complementary resources. With the economic incentive to maximize returns from its investments, a VC firm needs to decide whether to continuously invest in a portfolio company, or terminate an unpromising one on a dynamic basis (Fulghieri and Sevilir, 2009; Jovanovic and Szentes, 2013; Li and Chi, 2013). In most studies based on VC industries in established economies such as the US, a VC firm is modelled as an agent who collects and analyses all information (e.g., market volatility or quality of entrepreneurs) up to the current time and forecasts the future payoff. A VC firm will therefore discontinue an investment if the future expected payoff is not worth the investment.

Under weak institutions such as in many emerging economies, however, VC firms often have lower bargaining power in recouping returns from their investments. While studies based on the US and other developed countries assume that VC investments are well protected through legally-bounded contracts in business transactions, it might not always be the case in emerging markets with weak or less developed institutions (Hitt et al., 2004). For example, unlike the ‘vulture capital’ image in developed countries such as the US, VC firms in China are often less powerful in terms of monitoring and regulating entrepreneurs’ behaviours (Bruton and Ahlstrom, 2003).

To better understand how VC firms operate in an emerging economy with weak institutional protection, we collected qualitative data primarily through personal interviews conducted in China and complemented them with news reports and other sources. We have conducted more than 50 hours on-site interviews with over 35 stakeholders, including general partners, limited partners, entrepreneurs, scholars, and policy makers. Our semi-structured interviews with general partners primarily focused on how they make investment decisions, how to manage investment portfolios, and how to deal with challenges facing either the focal VC firm or the entire industry. Our qualitative investigation revealed that while VC firms in China generally follow well-known practices such as staging investments and forming syndicates, they do exhibit some interesting and unique characteristics that deserve a reconceptualization.

First, the entire VC industry is plagued by a lack of enforcement, even when the contractual arrangements are available (Batjargal and Liu, 2004). As one famous Chinese VC investor noted, ‘When I made an (VC) investment, I already put 75 per cent of risk in the company. I must depend on the start-up to produce or write off my investment… Besides, the contracts help little in terms of hedging the risk, you know what I mean, people risk’. As a result, VC firms have to manage their investment portfolio more effectively. To deal with the investment uncertainty, a VC firm not only takes the conventional approach such as diversifying investments, but also adopts approaches that hinge on the power relationship between the VC firm and its portfolio companies. Our study is therefore aiming to shed new light on how the VC firms’ decision making is embedded in the weak institutional context.

Second, VC firms rely more on the syndicate relationships with other VC firms to compensate the weak institutional protection, and therefore their decisions regarding the subsequent investment are more influenced by their embedded social relationships. The uncertainty of VC investments in China may arise from unexpected conflicts between the entrepreneurs and investors. For example, in the well-reported NVC Lighting Technology incident, after the investors fired the founder CEO (a painful but common practice in the VC community in Silicon Valley), he quickly initiated a public media retaliation, and even threatened to take away middle managers and clients to start a competing company. The drama ended up in a compromise between the two parties and the founder CEO later returned to his original post. This story, as well as several other notable incidents, illustrates that VC investments in China should be better viewed from social and relational perspectives.

As indicated by previous studies in the context of China, interpersonal and interorganizational relationships, or ‘guanxi’, were considered as valuable assets (Batjargal and Liu, 2004; Xiao and Tsui, 2007). Such relationships not only provide critical business information, but also help manage the interactions between a VC firm and its portfolio companies. As one senior investment manager from a leading domestic VC firm stated, forming a syndicate definitely pools capital and expertise but it is also motivated by seeking ‘powerful’ partners that can monitor the investments and intervene whenever necessary. Such partnering approach could be a double-edge sword in that those powerful syndicate partners are beneficial in terms of monitoring and regulating portfolio companies but they are also formidable if such syndicate relationship breaks up.

When it comes to investment termination, our qualitative data suggest that VC firms deliberate on terminations if they perceive an investment with little possibility of creating financial returns (e.g., regulation changes destroy the target market), but have to face tremendous uncertainty in making such decisions. Many VC firms have internal procedures (e.g. majority vote) but virtually none has a formal model to help make such decisions. For example, when being asked about their termination experiences, one general partner of a Beijing-based VC firm first introduced the formal procedure: if the partner associated with a deal raises a concern, they will hold a formal meeting involving not only the partner associated with the deal but also at least two other partners unrelated to the deal. This temporary committee will jointly decide whether to terminate a specific investment or not. However, he also added: ‘… you know, it is really a judgment call. Do you know X company? I vividly remember that their CFO almost cried to me for further investment due to lack of cash… We hesitated with some concerns… but several months later, it went public at NASDAQ, from the brink of a disastrous liquidation to an outstanding exit’.

Building on the qualitative investigation, we conclude that the social aspects of VC investments such as interdependence between a VC and its portfolio companies, as well as relational embeddedness among VC firms cannot be ignored when it comes to understanding VC operations in an emerging economy such as China.

Theoretical Development and Hypotheses

The dominant view on how a VC firm terminates an investment is to calculate the expected payoff, particularly with a dynamic consideration of all information collected up to the current time. For example, Li and Chi (2013) propose a real option perspective on VC investment termination and argue that perceived market volatility increases the expected future payoff of the focal investment and hence reduces the propensity to terminate. The real option approach is based on the premise that VC rights are well protected in a strong institutional context (e.g., the US) and VC firms can overcome the problem of information asymmetry with their portfolio companies so that the values of the different real options can be calculated by specifying their payoffs (Bellalah and Pariente, 2007). However, in a weak institutional context (e.g., China), this approach ignores power as an effective mechanism that can safeguard VCs’ interests (Fried and Hisrich 1994; Sweeting 1991). With sufficient power, VC firms are better able to retain effectiveness in managing their portfolio companies and preserve the option to abandon less promising ones.

We set out to investigate why a VC firm exercises discretion (i.e., takes actions based on its own judgement) over the termination of an investment, drawing on insights from both resource dependence and social network perspectives. Discretion is a core concept in the field of strategic management, which is defined as the latitude of action (Hambrick and Finkelstein, 1987). Discretion is also a distinct dimension of power, reflecting a firm's latitude to allocate and use a resource (Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003) in pursuit of its own interests (Goodrick and Salancik, 1996). Moreover, as Pfeffer and Salancik (2003, p. 257) noted, ‘to understand organizational behavior, one must understand how the organization relates to other social actors in its environment’. We show that a VC firm's discretion over investment termination is conditional upon its syndicate networks.

Investment Similarity and Investment Termination

VC firms constantly seek new and better investment opportunities that emerge over time and adjust their investment portfolio (Gompers and Lerner, 2004; Matusik and Fitza, 2012). Because it is difficult to allocate limited capital to maintain investments in all portfolio companies, continued investments in a less promising project can cost a VC firm not only its sunk capital but also potentially more promising opportunities. As such, a VC firm needs to rebalance the portfolio continuously to keep only those promising projects and companies and drop those less promising ones. As the number of portfolio companies that a VC firm invests increases, particularly in the same domain where these companies share comparable characteristics such as industry membership, we argue that a VC firm is more likely to exercise its discretion over the termination of an earlier investment.

Specifically, subsequent investments in the same domain change the power balance between a VC firm and its portfolio companies. According to resource dependence theory, when the VC firm has wider range of investment choices, it can have higher bargaining power toward any individual portfolio company (Hallen et al., 2014; Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003). Recent research suggests that a large VC portfolio may increase internal competition among portfolio companies for resources, implying an increased bargaining power for the VC investor (Inderst et al., 2007; Jääskeläinen et al., 2006). An increase in such power is especially important in the context of weak institutions where VC firms’ rights are not sufficiently protected. Firms with power are better able to regulate their relationships with exchange partners and make decisions to safeguard their interests (Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003). Powerful VCs can exert more effective control over their relationships with portfolio companies by imposing more detailed reporting requirements to make a more accurate decision (Mitchell et al., 1995; Sweeting, 1991). Moreover, as a VC firm makes more investments in a similar domain, it has more chances to get promising opportunities and thus are better able to exercise its discretion to terminate the less promising investments. In addition, more investments in the similar domain help VC firms to develop domain-specific expertise and accumulate valuable information and knowledge that can help make a better termination decision.

Hypothesis 1: When a VC firm has a greater number of investments in an industry following the initial investment in a given portfolio company in that industry, the VC firm is more likely to terminate the subsequent investment in the company.

Interplay of Resource Dependence and Network Relations

We propose a framework that explicitly specifies a VC firm's network connections to test their moderating effects on the focal firm's use of discretion. This approach is rooted in the network embeddedness view of firms, which has sparked a fruitful series of studies (Borgatti and Cross, 2003; Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1997). Collectively, this body of work shows that resource exchanges are embedded in their broader social context, as social forces can subtly affect individual actors’ behaviours and yield distinct predictions (Baker, 1984; Uzzi, 1997), particularly when the decision needs to be made in a highly volatile and uncertain environment (Pollock et al., 2004).

In the VC context, investing in start-ups is highly risky due to their liabilities of newness and smallness (Puri and Zarutskie, 2012). Syndicate partners are vulnerable to each other's actions and therefore they need to take into consideration of other partners’ reactions before their own actions. We argue that the network structure of a VC firm vis-à-vis other VC firms would influence the power balance/imbalance between the VC firm and its portfolio companies and therefore the termination decision. Our conceptualization starts with a network boundary defined by resource dependence to address this issue in the VC context. Specifically, building on the notion that an invested portfolio company can be viewed as a ‘setting’ where VC firms meet and form syndicates (Sorenson and Stuart, 2008), we propose two distinct network attributes within and beyond a portfolio company setting: deal network embeddedness, which is rooted in the deal-dependent VC network, and network access advantage, which arises from its connections to the deal-independent VC firms (Burt, 1992; Pollock et al., 2004; Rowley et al., 2005).

Given this distinction, we examine not only a VC firm's relations with its syndicate partners associated with a given portfolio company, but also the network access of a VC firm to other VC firms outside the focal syndicate investment. Our central argument is that deal network embeddedness will constrain the discretion of a VC firm because a VC firm's termination decisions can be partially left to the group consensus due to their shared duty and norm to manage the transactional interdependence with the portfolio company (Guler, 2007). By contrast, a VC firm with a superior network access is better able to take a discretionary action to pursue its own interests as subsequent syndicate opportunities are available. We develop hypotheses below to elaborate on the proposed framework.

Moderating Effect of Deal Network Embeddedness

Instead of being atomic players to make decisions, firms are often embedded in their social networks, and are substantially influenced by network attributes (Burt, 1992; Gulati, 1995). Firms participate in social networks because they are mutually dependent (Pfeffer and Nowak, 1976). As such, the socially embedded partners may not hold complete discretion to make an autonomous decision. In the VC context, syndicate partners are vulnerable to each other's actions and therefore they need to take into consideration of other partners’ reactions before their own actions. We argue that the network structure of a VC firm vis-à-vis other VC firms would strengthen the power balance between the VC firm and its portfolio companies and therefore the termination decision.

We argue that the embeddedness of a VC firm in a network of co-investors associated with a focal company will reduce the positive effect of similar investments in other companies on the termination of investment in the focal company. First, exchange networks can ‘be understood as a product of patterns of interorganizational dependence and constraint’ (Pfeffer, 1987, p. 40). VC partners have mutual dependence because their return jointly depends on the future of portfolio companies. When the embeddedness level is high, the VC partners are highly mutually dependent and therefore need more consideration on their reciprocal relationships with other partners. For example, prior research suggested that the leading IPO underwriter's embeddedness level with its partners will shape the equity pricing behavior, since the underwriter will consider the long-term implications with its embedded partners (Pollock et al., 2004). In our research context, when the focal VC firm has formed many syndicates with its focal VC partners associated with the focal company, it becomes more embedded in the setting-related transactional relationships (Fisher and Pollock, 2004). Dependence often serves as a critical factor that constrains the use of power because doing so may create the risk of retaliation such as a cut-off of the dependence relationship (Molm, 1997). Thus, high embeddedness constrains the VC firm's discretion to make a unilateral termination decision solely based on its own investment portfolio.

Second, established networks also provide social benefits such as increased trust and friendship beyond merely managing transactional interdependencies (Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003). When firms are embedded in a network of partners, the repeated interactions among partners increase information sharing, familiarity, and trust among them (Gulati, 1995). Therefore, the interactions among partner firms can be more effective and coordinated (Ma et al., 2013). The norms of exchange are developed because closely connected firms can collectively monitor and sanction deviant behaviours (Gulati, 1995). The collective norms can serve as a powerful interorganizational governance mechanism that prevents unexpected behaviours by individual firms (Gulati, 1995; Zaheer and Venkatraman, 1995). It has been found that the deep embeddedness in a network and dense connection among firms can facilitate and extend the longevity of collaborative relationship such as alliances or joint ventures (e.g., Rowley et al., 2005). Therefore, the embeddedness helps build the stable and reliable relationships between partner firms.

Hypothesis 2: A VC firm's deal network embeddedness with other VC firms in the deal-dependent network will reduce the positive effect of similar investments on the likelihood of investment termination.

Moderating Effect of Network Access Advantage

Interorganizational relationships may extend across different types of networks (Burt, 1992). A VC firm may also form other syndicates with different partners outside the syndicate formed with those VC partners associated with a given portfolio company. In this study, we focus on the VC firm's network position in the whole VC industry network beyond the setting or the focal portfolio company. Network access advantage (Burt, 1992; Guler and Guillen, 2010) reflects the degree of power advantage of a VC firm in the deal-independent network. Firms with high levels of network access advantage benefit from bridging structural holes or gaps in the social network by using a teritus gaudens strategy (i.e., the third party is the one that benefits) (Obstfeld, 2005). The syndicate network outside the focal relationship with a portfolio company provides advantages such as access to capital management experience, non-redundant information, and potential investment opportunities that are deemed as more promising.

From a power perspective, VC firms with a network access advantage in deal-independent networks are more likely to exercise their own discretion than those without such advantege. The power mechanism that underlies this explanation is as follows. In an exchange relationship between actor A and actor B, alternative sources of resources available to A outside the A-B relationship will increase the power of A relative to B (Emerson, 1962). One of the primary benefits of participating in social networks outside a setting is to gain power by controlling the access to alternative sources of resources (e.g., other companies) beyond the existing source of resources (e.g., the focal company). For example, Provan et al. (1980) found that agencies with more interorganizational linkages are more likely to increase their power relative to other agencies lacking such linkages, and therefore more likely to obtain funding from United Way. In the VC context, we argue that a VC firm's network access advantege can enhance the effect of similar investemnts because the VC firm is more likely to identify and select better opportunities in subsequent investments from a larger pool of alternative potential projects.

Thus, we argue that network access advantage will enhance the positive effect of subsequent investments in other similar companies on the termination of investment in the focal company. When network access advantage is high, a VC firm is in a desirable position to access diverse information through its ties with other VC firms that are sparsely connected in the VC industry (Hochberg et al., 2010). The VC literature has extensively documented the benefit of network access advantage in terms of connecting disparate partners as sources of information (Guler and Guillen, 2010; Sorenson and Stuart, 2008). From this viewpoint, for a VC firm with a network access advantage, terminating investment in the earlier invested companies reduces the opportunity cost of and increases the benefit from the more promising subsequent investments in the same industry.

Hypothesis 3: A VC firm's network access advantage with other VC firms in the deal-independent network will enhance the positive effect of similar investments on the likelihood of investment termination.

Method

Sample

The linkage between a VC firm and its portfolio companies in China provides a novel context to test our theoretical framework because the VC industry is relatively young and VC firms need to constantly make portfolio adjustments in a weak institutional environment. Nevertheless, the industry has reached a level comparable to its peers in developed countries. For example, VC firms in China in 2011 raised a total of 28.2 billion US dollars and invested 12.7 billion in a broad range of industries such as modern agriculture, clean tech, consumer products, Internet services, and manufacturing (Shi, 2012).

We collected longitudinal archival data primarily from the two leading VC information providers in China – ChinaVenture and Zero2IPO. We pooled information from the two sources to achieve maximum coverage because each source provided some information not covered by the other. The data structure of both databases resembles the US VC database – VentureXpert from Thomson Reuters, which has been extensively used by prior studies (Hochberg et al., 2010; Ma et al., 2013; Matusik and Fitza, 2012). We started with the deal table in the database that covers the key information regarding a VC deal such as the investment date, the invested company, and the investors. We then collected additional information such as exits by matching names of VC firms and portfolio companies to other tables in the same database. In case the information recorded in the two sources conflicted with each other (e.g., investment amount), we consulted with the data vendors and conducted our own research (e.g., asking industry participants) to determine the most sensible solution.

Although both databases contain deals dated back to 1993, our interviewees suggested that we should be cautious of early deals because Zero2IPO was founded in 2001 and ChinaVenture even later. We therefore dropped deals made prior to 2001 due to the reliability concern. We chose 2012 as the end of our observation period so that we could track VC deals for three years until 2015 to better evaluate their eventual outcomes (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013). We removed deals made by non-dedicated players such as investment banks or insurance companies. Following the suggestions of our interviewees, we also excluded deals for imminent IPOs, or so-called ‘pre-IPO’ deals, since they are almost certain to exit without continued investments. The sampling procedure yielded a final sample of 11,809 VC deals made by 1418 VC firms between 2001 and 2012. Altogether, these VC firms invested in 6180 portfolio companies, 1231 of which eventually went public via IPOs, such as Baidu at NASDAQ and Tencent at Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Another 325 portfolio companies experienced other exits such as acquisitions. A total of 909 out of the 1418 VC firms, or roughly 64 per cent, had at least one investment termination in the sample, leading to a total of 5930 investment terminations. The percentage is lower than the same statistic (87 per cent) reported in the US-based VC studies (Li and Chi, 2013).

Dependent Variable

Investment termination

Following prior studies (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013), we coded a company-VC relationship as terminated if the VC firm did not appear in any of the sequential investment rounds or if the focal round was also the final round of financing for the venture, excluding the final round prior to an IPO or other desirable exits such as mergers and acquisitions (M&As). In the former case, we assumed that the termination event occurred at the earlier rounds but the VC no longer appeared as an investor in subsequent rounds. In the latter case, we inferred the duration length from the empirical distribution of intervals between rounds of investments in our sample. Because 75 per cent of sequential deals in our sample were made within the next 417 days, we therefore took 417 days as the cut-off point, unless we observed otherwise. This estimation approach was adopted by the US-based VC studies, but our cut-off point (417) is shorter than theirs (Guler, 2007). As our interviewees indicated, the VC investment cycle is generally shorter in China than in the US, due to the rapid changes in China's economy and shorter investment horizon expected by VC firms.

Independent and Moderating Variables

Similar investments was measured by the number of active investments made by the focal VC firm in the same industry as the focal company from its initial investment until the investment in the focal company was terminated or exited via an IPO or an acquisition. A similar measure was adopted by Xia (2011) in his study of joint venture termination. As our informants suggested, VC investors are able to make comparisons across investments in the same domain due to the similarity when the number of invested companies in the same industry increases. We followed the national standard (or ‘Guo Biao’, GB in short) of industry classification adopted by most companies in China, and used the two-digit level industry codes.

Deal network embeddedness with syndicate partners associated with a portfolio company setting was measured by the sum of the percentages of its prior investments in a five-year backward-looking window, or five calendar years prior to the focal investment date, that were co-investments made by the focal VC firm with its syndicate partners (Fisher and Pollock, 2004). For example, assuming that three VC investors (firm A, B, and C) invested in a portfolio company (X) in 2006 and we examine whether A (the focal VC firm) terminated its investment in X, we will count the number of previous co-investments between A and B or C from 2002 to 2006 (IAB and IAC respectively), and also the number of investments made by A in the same period (IA). We then take the sum of IAB/IA and IAC/IA to obtain the values of the deal network embeddedness variable, which could therefore range from 0 to N, or the number of partners. For a deal made by only one VC firm, we assigned the negative value of −1 to indicate a lower embeddedness than that of a syndicated deal with zero percentage of prior co-investments. Our results are robust to other negative values (e.g., the median or mean of the non-zero embeddedness values).

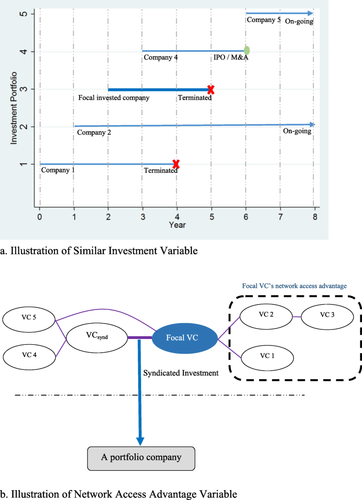

Network access advantage refers to the alternative partnering opportunities that a focal VC possesses independent of the focal syndicate investment. To construct this variable, we started from the focal VC firm's ego network and tracked all its first-degree and second-degree network connections that have no direct ties with the focal syndicate partner(s). Our operationalization is built on the assumption that a VC firm could reach out to this pool of VC firms who have no direct relationships with the focal syndicate partners to form alternative syndicates. The larger this pool of potential partners, the more discretion the focal VC firm is able to exercise with less reliance on its focal investment and hence more inclined to terminate a less promising investment. Similar to the construction of deal network embeddedness, we also took a five-year backward-looking window to include deals made in the prior five years to develop the ego-network for the focal VC. Figure 1 illustrates how we operationalized our key variables: similar investments and network access advantage.

Illustration of two key theoretical variables [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Control Variables

Other factors may also influence VC investment terminations. Accordingly, we included several controls at the environment, the dyad, the portfolio company, and the VC firm levels.

IPO market conditions

The primary exit option for most VC investments in China is still IPOs, or selling their stakes to public investors. VC investment behaviours are therefore subject to the fluctuation of public equity markets. To control for this impact, we measured IPO market conditions by the total number of VC-backed IPOs in the current year and in the same industry as the focal portfolio company (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013).

Round of investment

Previous studies have suggested that more rounds of financing by a VC firm may lead to a decreased hazard of sequential investment (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013).We thus included the round of investment for each VC investment.

Geographic proximity

We also created a dummy variable indicating whether the focal VC firm and the focal invested company are located in the same geographic region, such as the same province (1 yes; 0 no), roughly equivalent to the metropolitan statistical area variable, or MSA, used in the US VC studies (Hochberg et al., 2010).

Local VC availability

The portfolio company could leverage its bargaining power over its VC investors if it could access many alternative VC investors (Baker et al., 1998).We therefore included another control – local VC availability, measured by the number of VC firms in the same geographic region.

Top ranking ventures

As the quality of a portfolio company may affect investment termination, we controlled for a key quality indicator of the portfolio companies. Each year, Zero2IPO Group and Forbes China develop a ranking of the fast-growing start-ups in China. Their purpose is to promote the visibility of promising start-ups and entrepreneurial culture in China. Since the judgment panels primarily consist of leading VC investors, the selected companies are often high-quality start-ups with tremendous growth potential. We created a dummy variable, top ranking ventures, to indicate whether a portfolio company had ever been included in either Zero2IPO's or Forbes China's list, coded as 1 if yes and 0 no.

We also controlled for some important VC firm characteristics. In the China context, a VC firm may raise funds from foreign limited partners, often denominated in US dollar (USD), or from domestic parties such as wealthy individuals and government agencies, typically denominated in Chinese Renminbi (RMB). Foreign funds may operate in a different manner from domestic funds in terms of maturity and governance. To allow for such differences, we included another control – VC fund type, coded as 0 for a domestic fund, 1 for a hybrid one, and 2 for a foreign fund. VC fund age was measured by the difference between the current investment year and the fund vintage year. VC experience was measured by the total number of investments made by the focal VC firm up to the focal round of investment. VC portfolio size was measured by the total number of active investments that the focal VC made and held.

VC industry diversification

Finally, we controlled for the strategic consideration of portfolio balancing by VC firms (Matusik and Fitza, 2012). VC industry diversification was measured by a Herfindahl index, or 1 - Σ

, where Pi is the proportion of all of a firm's investments made in the five-year backward-looking window that were made in industry i. VC firms in China are generally more diversified than their peers in the USA. Our interviewees attributed this phenomenon to the rapid growth of China's economy in virtually every industry. For example, IDG Capital Partners, arguably the most prominent VC firm investing in technology and Internet start-ups in China, had invested in more than 20 consumer products or services companies (e.g., clothing and hotel).

, where Pi is the proportion of all of a firm's investments made in the five-year backward-looking window that were made in industry i. VC firms in China are generally more diversified than their peers in the USA. Our interviewees attributed this phenomenon to the rapid growth of China's economy in virtually every industry. For example, IDG Capital Partners, arguably the most prominent VC firm investing in technology and Internet start-ups in China, had invested in more than 20 consumer products or services companies (e.g., clothing and hotel).

Analyses

We estimated the hazard of terminating a VC investment with the semi-parametric Cox model, as suggested by several studies in similar contexts (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013). The Cox model is superior to parametric specifications such as the Weibull model because it does not assume the shape of the underlying hazard rate function. Such a benefit is especially welcome in a context of unknown hazard rate functions and few ties of events. We did, however, obtain consistent results when we experimented with other specifications such as the Weibull or Gompertz model. We carried out the Cox model with the ‘stcox’ command in STATA 13. Since our analysis is at the company-VC dyad level, we structured each deal as a spell, from the focal investment date to the next round investment date, or censored by termination or exit events (for an illustrative table, see (Guler, 2007, p. 265)). Finally, we used the Huber-White-sandwich estimator to derive robust standard errors, clustered on portfolio companies.

Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations of each variable included in the study and their correlations. Most correlation coefficients are small except those of the VC firm characteristics. The mean of variance inflation factors (VIFs) is 2.48 with a maximum of 5.09, below the suggested threshold level of 10 (Kutner et al., 2004). We also applied the ‘coldiag2’ command in STATA to further examine potential multicollinearity issues. The command yielded a maximum condition number 13.72, well below the threshold of 30 (Belsley et al., 1980). Together, these tests suggested alleviated multicollinearity concerns in our analyses.

| Variable | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. IPO market conditions | 103.79 | 67.45 | |||||||||||

| 2. Local VC availability | 1.56 | 1.97 | .31 | ||||||||||

| 3. Top ranking ventures | 0.08 | .41 | –.03 | .01 | |||||||||

| 4. Round of investment | 1.57 | .94 | .06 | .16 | .01 | ||||||||

| 5. Geographic proximity | .26 | .44 | –.04 | .02 | –.02 | –.07 | |||||||

| 6. VC fund type | .92 | .82 | –.11 | .02 | .03 | .16 | –.29 | ||||||

| 7. VC fund age | 3.32 | 2.4 | –.01 | .03 | .02 | .04 | .06 | .02 | |||||

| 8. VC experience | 2.5 | 1.61 | .16 | .07 | .01 | .04 | .09 | .06 | .46 | ||||

| 9. VC industry diversification | .66 | .37 | .09 | .04 | .01 | 0 | .07 | .04 | .36 | .32 | |||

| 10. Similar investmentsc | 0 | 6.79 | –.15 | 0 | 0 | –.06 | .09 | –.01 | .18 | .27 | .22 | ||

| 11. Deal network embeddednessc | 0 | .58 | –.04 | .11 | .04 | .24 | 0 | .18 | .06 | .09 | .04 | .01 | |

| 12. Network access advantagec | 0 | .99 | .02 | –.01 | 0 | –.05 | –.01 | –.04 | .1 | .16 | .05 | .02 | –.03 |

- Note: N = 11,809; correlation coefficients above |0.02| are significant at 0.05 level; c: the variable is mean–centred.

Table 2 presents the Cox regression estimates of our theorized variables on the hazard of VC investment termination. We first entered the control variables (Model 1) and then the hypothesized variables (Models 2, 4, and 6). Model 7 is the full model that includes all the variables and the interaction terms. For control variables, we obtained some comparable results to the ones found by previous studies conducted in the US VC industry. For example, similar to Li and Chi (2013), we also found that VC experience is negatively and significantly related to the propensity to terminate sequential investment. Like Guler (2007), we did not find a significant impact of geographic proximity on the likelihood of investment termination. We did, however, find that foreign VC firms are more likely to terminate than domestic ones, a result that may arise from the unique context of China. The overall model fitness improves in terms of log likelihood, increasing from −49,147 for the baseline model (Model 1) to −48,713 (p < 0.001) for the full model (Model 7).

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPO market conditions | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01** |

| (−34.60) | (−32.27) | (−32.10) | (−32.08) | (−32.34) | (−32.55) | (−32.46) | |

| Local VC availability | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.03* | −0.03* |

| (−2.83) | (−2.96) | (−2.95) | (−2.91) | (−2.92) | (−2.91) | (−2.85) | |

| Top ranking ventures | −0.09 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| (−0.34) | (−0.05) | (−0.24) | (−0.29) | (−0.07) | (−0.06) | (−0.31) | |

| Round of investment | −0.09** | −0.08** | −0.10** | −0.10** | −0.09** | −0.09** | −0.10** |

| (−3.43) | (−3.18) | (−3.59) | (−3.62) | (−3.25) | (−3.25) | (−3.63) | |

| Geographic proximity | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| (0.42) | (0.05) | (−0.03) | (−0.05) | (0.02) | (−0.05) | (−0.17) | |

| VC fund type | 0.06** | 0.12** | 0.11** | 0.11** | 0.12** | 0.11** | 0.10** |

| (2.71) | (5.66) | (5.20) | (5.19) | (5.52) | (5.26) | (4.79) | |

| VC fund age | 0.04** | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.04** | 0.03* |

| (5.51) | (4.83) | (4.63) | (4.49) | (4.82) | (5.41) | (5.16) | |

| VC experience | −0.19** | −0.33** | −0.33** | −0.33** | −0.32** | −0.33** | −0.33** |

| (−14.15) | (−23.17) | (−23.49) | (−23.56) | (−22.69) | (−23.07) | (−23.48) | |

| VC industry diversification | 0.21** | 0.35** | 0.36* | 0.36* | 0.36* | 0.35* | 0.36* |

| (3.87) | (6.27) | (6.34) | (6.40) | (6.33) | (6.23) | (6.32) | |

| Similar investments | 0.06** | 0.06** | 0.06** | 0.06** | 0.07** | 0.07** | |

| (27.26) | (27.23) | (27.13) | (27.40) | (27.88) | (27.16) | ||

| Deal network embeddedness | −0.12** | −0.11* | −0.09** | ||||

| (−4.04) | (−3.67) | (−2.87) | |||||

| Similar investments X Deal network embeddedness | −0.01* | −0.02** | |||||

| (−3.69) | (−5.30) | ||||||

| Network access advantage | 0.04** | 0.05** | 0.05** | ||||

| (2.78) | (3.32) | (3.38) | |||||

| Similar investments X Network access advantage | 0.01** | 0.01** | |||||

| (4.46) | (4.94) | ||||||

| Observations | 11,809 | 11,809 | 11,809 | 11,809 | 11,809 | 11,809 | 11,809 |

| Wald Chi-square | 1508 | 2716 | 2717 | 2790 | 2723 | 2772 | 2834 |

| Log likelihood | −49,289 | −48,949 | −48,938 | −48,929 | −48,944 | −48,931 | −48,907 |

| −2* ΔLog likelihood (In contrast to Model 1) | 680** | 702** | 720** | 690** | 716** | 764** | |

| −2* ΔLog likelihood (In contrast to Model 2) | 22** | 40** | 10* | 36** | 84** |

- Robust z-statistics in parentheses.

- ** p<0.01, * p<0.05, † p<0.1, two-tailed tests.

Hypothesis 1 states that the number of subsequent investments in the same industry after a focal portfolio company by a VC firm will increase the hazard of investment termination in the focal portfolio company. In Model 2, the coefficient of similar investments is positive and significant (β = 0.06, p < 0.01). This effect is robust across various specifications (e.g., β = 0.07, p < 0.01 in Model 7 or the full model), lending support to Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 predicts that deal network embeddedness will reduce the positive effect of similar investments on the hazard of investment termination. In Model 7, the interaction term between similar investments and deal network embeddedness is negative and significant (β=-0.02, p < 0.01). This result suggests that when holding similar investments constant, increasing deal network embeddedness will increase the reliance of a VC on its syndicate partners and reduce the discretion the focal VC possesses over its focal portfolio company. Hypothesis 2 is therefore supported.

Hypothesis 3 states that network access advantage can balance the reliance of the focal VC on its syndicate partners due to the alternative partner choices. It therefore strengthens the positive impact of similar investments on the hazard of terminating sequential investments. As seen in Model 7, the coefficient of the interaction term between similar investments and network access advantage is both positive and significant (β = 0.01, p < 0.01). Hypothesis 3 is also supported.

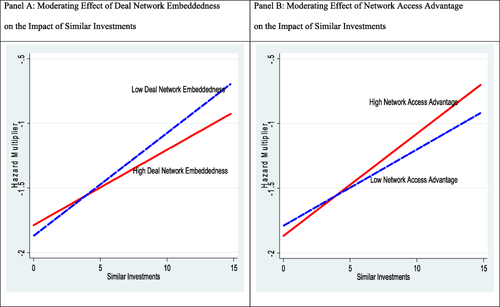

Figure 2 illustrates the two separate moderating effects. Both Panel A and B show that, as a VC firm's similar investments increase, the hazard of terminating the focal investment also increases (i.e., the upward slopes). Panel A shows that this effect is contingent upon the deal network embeddedness such that, when deal network embeddedness is high (one standard deviation above the mean), the positive impact of similar investments on the hazard of termination is reduced (the solid blue line with a flatter slope). By contrast, Panel B shows that a VC firm's network access advantage outside the syndication setting exhibits a positive moderating effect on the relationship between similar investments and the hazard of investment termination. A VC firm with a high level of network access advantage is more likely to terminate sequential investments (the solid blue line with a steeper slope) than one with the same number of similar investments but a low level of network access advantage (the dashed read line with a flatter slope). If we disregard the moderating effects and examine only the impact of similar investments (β = 0.06, p < 0.01), when similar investments increase by one standard deviation (i.e. 6.79), the log of hazard rate will increase approximately 0.72. Such small beta (β = 0.06), however, means significant increase in conditional possibility of investment termination. If a VC firm increases its similar investments to 7, the possibility of its terminating any one of the similar investments will almost double. If the focal VC also possesses a favourable network access advantage, the termination possibility will increase even further, which means faster termination decisions and more terminations in practice.

Graphs of moderating effects [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Post-Hoc Analyses and Robustness Tests

We conducted several post-hoc analyses and robustness tests to bolster the results reported above. First, VC investment termination may be caused by interorganizational imitation or vicarious learning from partners (Haveman, 1993). To assess this effect, we created another control variable, partner past termination, measured by the total number of terminated investments made by a VC firm's syndicate partners in the same industry within five preceding years. The new control exhibited only a marginally positive impact on the propensity to terminate investments. We also experimented with other measures such as the total number of terminations by all syndicate partners across industries. Regardless of the measure, our key findings remain consistent.

We have experimented with an alternative measure on similar investment. Specifically, we counted only on-going investments in the same stage and geographic scope. We treated Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen as the same ‘region’ since virtually all our interviewees suggested that they treated these big cities as the same in their portfolio consideration. The results remain stable. In fact, our key variable similar investments becomes even more significant (β = 0.22, p < 0.01 Model 2). Moreover, network access advantage could be confounded with other factors such as the focal VC firm's past success or reputation. To address this concern, we constructed a VC reputation variable following prior studies (Lee et al., 2011). Since the VC reputation variable is a comprehensive measure that considers several aspects such as VC fund size and VC experience, we removed VC experience and VC portfolio size to avoid multicollinearity. Nonetheless, our key findings remain robust to the new control variable.

We also tested other controls such as syndicate size, measured by the number of syndicate partners associated with the focal VC deal. Like Guler (2007), we found no significant impact of the syndicate size on the propensity to terminate VC investments. A VC firm's decision to terminate an investment could be influenced by the sunk cost, or the previous amount of investment (Staw et al., 1997). We assessed this possibility by including the amount of last round investment made by the focal VC firm (logged to avoid skewness) in our estimation. We also generated an alternative measure operationalized by the accumulative amount of all previous investments made by the focal VC firm should the deal investment amount is available (approximately 65 per cent deals have amount information). We found that neither investment amount had a significant impact on the propensity to terminate investments (e.g., total cumulative amount has an estimated β of 0.03, p > 0.1). Moreover, we conducted another robustness test to exclude desirable exits such as IPOs and M&As. Our key findings remain robust. For example, the key variable or similar investments still exhibits a positive and significant impact on investment termination (β = 0.07, p < 0.01). To make our study comparable to those using US VC data (Guler, 2007; Li and Chi, 2013), we used 482 days as the cut-off period to determine termination. Our results remain roughly unchanged.

In terms of econometric specifications, we provided two additional tests. First, we considered the competing risk of an invested company going bankrupt or failing (Lunn and McNeil, 1995). Applying the ‘stcrreg’ command in STATA, we found that, even after controlling the parallel risk of failure, our key theoretical variables still demonstrate similar impacts on the propensity to terminate the focal investment. For example, the direct impact of similar investments remains positive and significant (β = 0.07, p < 0.01), while the interaction between similar investments and deal network embeddedness is similarly negative and significant (β=-0.01, p < 0.05). The other test was to adopt a mixed level survival model or the recently available STATA command ‘stmixed’ (Crowther, 2014). Our key results are robust to this new specification too.

Discussion and Conclusion

We set out to investigate why VC firms terminate their investments in an emerging economy setting from a resource dependence perspective. We contend that answering this question needs to consider not only the dependence relationship between the focal VC firm and its portfolio companies, but also network relations between the focal VC firm and other VC firms. Our results show that the number of on-going similar investments in a VC's portfolio increases the propensity to terminate the focal investment. A VC firm's deal network embeddedness reduces the positive effect of similar investments on the propensity to terminate an investment. In contrast, a VC firm's network access advantage enhances such effect. These findings have both theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

Resource dependence theory provides a valuable perspective to examine why firms make certain decisions such as board member selection, strategic alliance partnerships, and corporate divestures given their idiosyncratic power relationships embedded in both transactional exchanges and social networks (Casciaro and Piskorski, 2005; Hillman et al., 2009). Meanwhile, the social network literature has well established the notion that a firm's discretion is constrained or enhanced by its network connections with other firms (Rowley et al., 2005; Uzzi, 1997). Our study makes a contribution by integrating insights from the two streams of research for a better understanding of investment termination decisions.

Specifically, when the focal VC firm is in a favourable bargaining power position vis-à-vis its portfolio company, the propensity to terminate the focal investment increases (Hallen et al., 2014). In line with earlier studies (Greve et al., 2013; Xia, 2011), our findings add to the literature by showing that terminating an investment is related to exploring emerging promising opportunities. Earlier studies have focused on how interdependencies drive network formation (Pfeffer and Nowak, 1976). More recent studies show that interdependencies also explain why firms terminate their interorganizational relationships such as interlocking director dismissal (Cowen and Marcel, 2011) or joint venture termination (Xia, 2011). Since VC investments are inherently risky, they require VC firms to take discretionary actions in pursuit of superior returns. Our findings support the idea that a VC firm is more able to exercise its discretion to choose from a large number of similar investments.

Moreover, existing studies on interorganizational relationships neglected the moderating effects of network attributes on firm's bargaining power over its vertical exchange parties. Our study extends this line of discussion by showing that such effects may play an important role. Our study explicitly defines the network boundary of resource dependence and specifies conditions under which a VC firm's social networks constrain or enhance its use of discretionary power when making an investment termination decision. In particular, this study advances the view that a portfolio company provides a unique ‘setting’, or the nexus of transactional and social connections among a VC firm, the focal invested company, and other VC firms (Sorenson and Stuart, 2008). The notion of setting helps identify the resource dependence relationships in VC peer network so that we can precisely investigate the conditions under which a firm's network may constrain or enhance its discretionary actions when pursuing its own interests, which have rarely been examined in existing studies. On the one hand, we explore the distinct implications of two types of networks by developing a framework that highlights the importance of advancing resource dependence research from a single exchange relationship to a multiplexity of interorganizational relationships.

What remains unclear from the network literature is the moderating impact of social embeddedness on a firm's discretion for its own interests (Borgatti and Foster, 2003). Drawing on insights from existing network research, our study has taken one step further by showing that deal network embeddedness essentially captures the level of clique-like cohesion among VC firms associated with a given company, while network access advantage indicates the information and advice benefits derived from structural holes (Burt, 1992). When facing different demands from partners within and outside the deal-dependent network, a firm may need to ‘balance operation’ (Emerson, 1962, p. 35). The critical insight of our theory is that deal network embeddedness of a VC firm associated with the setting, and network access advantage beyond the setting, may play different moderating roles when it comes to the investment termination decision.

Our findings provide evidence that, beyond managing its own investment portfolio, a VC firm is likely to consider its deal network embeddedness around a particular setting associated with the jointly invested company. When making a termination decision, the VC firm needs to consider not only the mutual dependence pressure, but also the relational pressure for escalation of commitment (Guler, 2007; Staw, 1981; Staw et al., 1997). The discretion of an individual VC firm to terminate its investment can be constrained by deal network embeddedness via its discretion over its portfolio companies. As a result, the firm can be reluctant to terminate additional rounds of investment or de-escalate commitments in the existing company even when its barging power of the portfolio company enables it to make such decision. Our findings therefore extend the existing studies that have demonstrated the direct impact of network embeddedness by showing its indirect impact on constraining the bargaining power of the focal organization (Rowley et al., 2005).

In a departure from prior research, our theoretical development also focuses on the network as an alternative source of resources, which allows a firm to have some power advantages to manage the setting or portfolio company (Emerson, 1962; Pfeffer and Salancik, 2003). The results lend support to our arguments on leveraging network access advantage, which specifies the potential partnering opportunities arising from its network advantage beyond the deal-related setting. This network access advantage enables a VC firm to access disconnected partners for non-redundant information and alternative opportunities that are potentially more promising. In particular, this type of advantage provides a VC firm with alternative sources of resources such as information and experience beyond the focal portfolio company setting, which allows the VC firm to identify and realize a broader range of potential opportunities that newly emerge (Burt, 1992; Guler and Guillen, 2010), and enhances its discretion to take an action such as a sequential investment termination in the earlier invested company. Together, these findings support our theory that a firm's vertical bargaining power can be altered by its social network attributes.

Practical Implications

This study also has important practical implications. For VC investors, our study offers a conceptual framework to explain and predict termination decisions. It has been studied that VC network attributes shape VC decisions such as international entry and partner choices (Guler and Guillen, 2010; Sorenson and Stuart, 2008). However, existing studies do not explicitly address the boundary issue of social networks, and thus do not address whether syndicate networks constrain or enhance a VC firm's discretion to take a particular action such as termination. Similar to the financial firms that make loans to industrial companies (Stearns and Mizruchi, 1986), a VC firm also needs to monitor and adjust its interdependent relationship with its portfolio companies. To manage their investment portfolio effectively, VC firms must carefully examine their ego networks, both associated with the focal portfolio company or the setting, and beyond the setting.

For the invested companies or start-ups, the structural change of a VC firm's portfolio can provide signals to predict the likelihood of the VC firm's termination decision. Increases in similar projects expand the range of choices for the VC firm to exercise its discretionary power, leading to an increased hazard of terminating sequential investment in the company. As one experienced entrepreneur summarized, seeking investments from large VC firms is a mixed blessing (Zheng, 2011). On the one hand, VC firms with a large portfolio of similar investments show their strategic focus in this domain. On the other hand, for each individual investment, particularly the earlier ones, it may signal less attention or eventual termination.

Limitations and Future Research

There are some limitations in this study, which may represent promising opportunities for future research. First, we tested our theoretical framework in China due to its rapidly growing economy and the critical role of the VC industry in the economy. The fact that our tests were based on a single-country setting may have limited the generalizability of the findings. Indeed, if the unique institutional environment in China makes the resource dependence logic more pronounced, we will expect such an effect to decrease in some developed countries such as the USA or UK with well-established institutions. However, the fundamental dependence relationship between VC firms and portfolio companies, as well as the embedded relationship among VC partners, also exists in other contexts. Second, in line with most existing studies (Ma et al., 2013), we have focused on the VC firms’ actions. Future research may investigate the perspective of the portfolio company on how the VC firm's characteristics impact portfolio companies (Ozmel et al., 2013), which may help us gain a more complete understanding of the relationship between portfolio companies and VC firms. Third, due to lack of information in the China VC data sources, we were unable to include controls such as cash available for investment or the life span of VC firms. Future studies with improved data coverage can obtain more accurate estimates and interesting insights.

In addition, one of our supplementary tests shows that the proposed interdependence effects appear to be more pronounced in domestic VC firms than in foreign VC firms. In an unreported analysis, we found that, within domestic VC firms, privately owned VC firms exhibited a slightly higher propensity of terminating investments than state-owned VC firms. That is, both foreign and private VC firms seem to exert stronger discretion than state-own VC firms, perhaps due to their flexible decision making procedures and close alignment between performance and incentive. These results seem to suggest that different fund ownership structures may exhibit different investment tendencies, which encourages future studies to explore the nuances of our proposed framework (Dushnitsky and Shapira, 2010; Zheng, 2011).

CONCLUSION

With a holistic consideration of both vertical and horizontal resource dependence relationships, our study represents a major foray into studies that examine how VC firms make investment termination decisions in an emerging economy context. We propose a framework that explains not only the direct impact of a VC firm's network attributes but also their interactions with the firm's vertical dependence relationship. Our theoretical framework and empirical findings have important implications for future research that attempts to integrate different theoretical perspectives. We hope our study opens a door for future research to further explore the interesting phenomenon of interorganizational relationship termination.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor Don Siegel, three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback. We also appreciate assistance from Ryan Wang, Arjyo Mitra and Judy Zhu for data collection and coding. This research was supported by the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project code: HKU 793513B) and partly by Seed Fund for Basic Research (Project code: 201509159005). All errors are ours.