The Peripheral Halo Effect: Do Academic Spinoffs Influence Universities' Research Income?

ABSTRACT

Extant literature has drawn attention to the ‘halo effect’ of the good reputation of a core organizational activity on the outcome of a peripheral activity. We contribute to the literature on organizational reputation by illustrating a halo effect in the opposite direction – from the periphery to the core. We show that developing a reputation for a peripheral activity (in our context, universities' social impact via spinoffs) may have positive spillovers for core organizational activities (in our context, university research), a phenomenon we term the ‘peripheral halo effect'. We also show that this effect is more prominent for high-status than for low-status organizations. Our research also contributes to the academic-entrepreneurship literature by revealing that spinoff portfolios can generate income for universities not only directly via equity positions but also indirectly via reputational benefits.

INTRODUCTION

Organizational reputation refers to stakeholders' perceptions about an organization's ability to create value relative to competitors (Rindova et al., 2005). Organizations build reputation through signals, including patterns of resource deployment and levels of performance and through endorsements from third parties such as the media (Deephouse, 2000; Dimov et al., 2007; Greenwood et al., 2005; Rindova et al., 2007). As organizations acquire reputation, they can attract more resources from their environment and enjoy better financial performance (Podolny, 1993; Roberts and Dowling, 2002).

Early seminal research in psychology has also recognized that an individual or an organization can gain better evaluations for one activity by being good at another. This phenomenon, termed as the ‘halo effect’ (Thorndike, 1920, p. 25), occurs because raters have difficulty treating an individual or an organization ‘as a compound of separate qualities and to assign a magnitude to each of these in independence of the others’ (Thorndike, 1920, p. 28; see also Cooper, 1981a, 1981b). The current literature has examined the halo effect of reputation for a core (i.e., central) activity on the outcome of a peripheral (i.e., secondary) activity. For example, in academic entrepreneurship, the halo effect enables universities with a strong reputation in research to license more than their less reputable counterparts for an equal amount of research (Sine et al., 2003).

Cognitive psychology research on heuristics (mental shortcuts) (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974) would suggest that the halo effect of reputation might not work only in one direction – from the core to the periphery – but could also exert the inverse effect of working from the periphery to the core. In essence, evaluators could form impressions of the organization based on a peripheral activity, which might then subconsciously transfer to evaluations of the core activity via the enactment of heuristics. However, the reputation literature has not yet empirically investigated such an effect, even though it is important for various aspects of organizational practice. For example, if a computer company develops a reputation for producing music players or phones (a peripheral activity), can this positively influence how customers evaluate its core computer business? In practice, organizations often attempt to benefit from such an effect. For example, mass-production car manufacturers may launch peripheral special-edition models (a ‘halo-car', as labelled by industry analysts), not aiming at profits, but hoping to increase interest in their core models (http://editorial.autos.msn.com/cadillac-still-has-plans-for-halo-car); and corporations often launch peripheral, corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities to demonstrate ethical behaviour also in the hope of benefiting financial performance (Brown and Perry, 1994; McGuire et al., 1990). Some corporate social responsibility initiatives are even considered ‘greenwash', namely peripheral initiatives for the sole purpose of enhancing the core, profit-making offering of the organization (Chen and Chang, 2013; Parguel et al., 2011).

In this study, we empirically investigate whether developing an organizational reputation for a peripheral activity can generate positive spillovers influencing the evaluations of the organization's core activities. We draw on organizational reputation theory (Lange et al., 2011; Rindova et al., 2010) to test the effect of three types of signals for a peripheral activity, namely signals of effort and performance, projected by the organization (Stiglitz, 2000), and signals refracted by the media (Fombrun and Van Riel, 1997; Rindova, 1997; Rindova and Fombrun, 1999). We argue that these signals build a reputation for a peripheral activity, which raises evaluations for the core activity via the enactment of heuristics (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974).

Moreover, drawing on social psychology research that suggests that the status of the sender of a message affects its acceptability by receivers (Giffin, 1967; Halperin et al., 1976; Hovland et al.,1953;), we propose status as an important moderator of the relationship between signals for a peripheral activity and evaluations for the core activity. Status is an intangible asset (Sauder et al., 2012; Stuart and Ding, 2006) that is clearly delineated from the concept of reputation; status captures differences in social rank, whereas reputation captures perceived merit (Piazza and Castellucci, 2014; Sorenson, 2014; Washington and Zajac, 2005). We argue that, when status is high, signals for a peripheral activity increase favourable evaluations for the core to a greater extent than when status is low. This is because signals from high-status organizations are more credible, as high-status organizations are considered reliable sources of information (Giffin, 1967; Sine et al., 2003).

We test these arguments with a novel longitudinal database (1993−2007) of academic spinoffs, new firms created to commercially exploit knowledge, technology, or research results developed within a university. Our dataset tracks the population of English and Scottish universities and their spinoffs since the inception of the phenomenon in the UK. Academic spinoffs are important sources of innovation and economic growth (Rothermael et al., 2007). We test our broader thesis in the university context by measuring the size, performance, and media coverage of a university's spinoff portfolio, which represent signals of social impact (a peripheral activity for universities). We then test whether such signals of social impact are associated with income for research (a core activity for universities).

From a phenomenon perspective, our paper investigates for the first time whether spinoffs make money for their universities indirectly by influencing research income. Recent progress in the booming literature on academic entrepreneurship has revealed a range of drivers of spinoff emergence (Clarysse et al., 2011b; Colyvas, 2007; DiGregorio and Shane, 2003; Fini et al., 2010; Lockett and Wright, 2005; O'Shea et al., 2005), growth and performance (Clarysse et al., 2011a; Zhang, 2009; Zerbinati et al., 2012). The literature has also investigated the impact spinoffs have on jobs and the economy (Grimaldi et al., 2011; Rothaermel et al., 2007). However, the literature seems preoccupied with the spread of spinoffs and has largely displaced the issue of how spinoffs affect the universities that generate them (Shane, 2004, p. 3). Some recent studies have examined the impact of academic entrepreneurship on academic indicators such as research productivity (Buenstorf, 2009; Lowe and Gonzales-Brambila, 2007; Toole and Czarnitzki, 2010), faculty learning and creativity (Perkmann and Walsh, 2009), and faculty retention (Nicolaou and Souitaris, 2013). Our paper extends this emerging research stream by testing the association between spinoff activities and a university's sponsored research income from public research councils and the industry.

The study makes three major contributions. First, we contribute to the theory on organizational reputation. We illustrate that developing a reputation for a peripheral activity (in our context, universities' social impact via spinoffs) is associated with evaluations for the core organizational activity (in our context, research). We refer to this phenomenon as the peripheral halo effect.

Second, we contribute to the research on the interdependency between reputation and status by revealing that organizational signals are interpreted differently depending on the status of the sender. We find that the peripheral halo effect is more prominent in high-status than in low-status organizations.

Third, we contribute to the literature on academic entrepreneurship by illustrating that the characteristics of a university's spinoff portfolio are related to research income over and above the amount expected from the university's research performance and general reputation. Given that the returns from university equity positions in spinoffs have proved negligible (Bok, 2003; Shane, 2004; Slaughter and Leslie, 1997), the reputation perspective focuses, instead, on the indirect effects of spinoffs on university research income.

THEORY

Organizational Reputation

The management literature on organizational reputation examines how stakeholders perceive organizations in comparison to their competitors (Lange et al., 2011). Organizations build reputation through signals sent by their actions and also by endorsements from third parties such as the media (Basdeo et al., 2006; Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Rindova et al., 2007).

The literature distinguishes between two interrelated but distinct dimensions of reputation, namely perceived quality and prominence (Rindova et al., 2005). Perceived quality refers to how stakeholders evaluate a particular organizational attribute and is underpinned by an economic perspective (i.e., signalling theory). The perceived quality dimension of reputation is influenced by signals from an organization's past actions and performance (Basdeo et al., 2006; Fombrun and Shanley, 1990). Signalling theory (Spence, 1973) describes behaviours when two parties (a sender and a receiver) possess different information, a phenomenon called information asymmetry (Stiglitz 2000). The sender's actions signal relevant information about an underlying, unobservable ability. The receiver interprets the signal and adjusts his/her behaviour accordingly, which can benefit the sender (Connelly et al., 2011).

Conversely, the prominence dimension of reputation is derived from a sociological perspective and captures the collective awareness and recognition that an organization has accumulated in its field. Prominence is influenced by the choices that influential third parties such as high-status actors and the media make vis-à-vis the organization (Deephouse, 2000; Pollock and Rindova, 2003; Rao, 1994; Stuart, 2000). Stakeholders closely watch the choices of such actors because of their perceived superiority in evaluating firms (Rao, 1994; Stuart, 2000). Therefore, the prominence dimension of reputation is socially constructed and is based on the concept of endorsement.

In general, we lack studies that disentangle empirically the effects of reputation for different domains of an organization's activity (Dimov and Milanov, 2010; Lange et al., 2011). In this study, we focus on reputation as an assessment for a specific organizational activity (what Lange et al., 2011 called ‘being known for something') rather than an overall generalized assessment of the organization's favourability. According to Deutsch and Ross (2003, p. 1004), ‘Firms can develop reputations for many aspects others care about. For example, a firm may be seen as having a reputation for high-quality products, poor labour relations or questionable environmental practices.'

The Halo Effect

By halo effect, the psychology literature refers to the influence of a core evaluation on evaluations of specific attributes (Murphy et al., 1993; Nisbett and Wilson, 1977; Thorndike, 1920). Much of the early research on the halo effect focused on individuals and more specifically on physical attractiveness and how this attribute affected the judgments of raters on other individual attributes (Dion et al., 1972). For example, Downs and Lyons (1991) found that the attractiveness of a defendant was associated with judges levying lower sentences in misdemeanour cases. Similarly, in the context of academia, Wilson (1968) found that estimates of an academic's height were affected by his or her ascribed status (i.e., demonstrator, lecturer, senior lecturer, professor), while Peters and Ceci (1982) demonstrated that the halo effect of institutional affiliation influenced whether an academic's paper was accepted or rejected by a journal.

Research on the halo effect has also taken place at the organizational level of analysis. Early research has recognized the positive effect of reputation of the core organizational activity on the outcome of a peripheral activity (Crane, 1965; Perrow, 1961). For example, the halo effect of reputable universities enables them to license more than their less prominent counterparts (Sine et al., 2003). Cognitive psychology research on heuristics (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974) suggests that the halo effect could also work in the reverse direction, from the periphery to the core. However, the reputation literature has not yet empirically investigated whether developing a reputation for a peripheral activity can positively relate to the organization's core activity.

Periphery comes from the Greek word periphereia and is defined as ‘a marginal or secondary position in or aspect of a group, subject or sphere of activity'. Instead, core is defined as ‘the part of something that is central to its existence or character’ (Oxford English Dictionary, www.oxforddictionaries.com). Prototype theory in cognitive psychology (Rosch and Mervis, 1975; Rosch et al., 1976) and recent work on social categorization (Bitektine, 2011; Durand and Paolella, 2013) are relevant for making a distinction between core and peripheral organizational activities. Prototype theory argues that objects, animals, organizations, and activities can be classified as members of a category by comparing them to a prototype (Hampton, 1979; Rosch, 1973; Rosch and Mervis, 1975;). ‘Prototypes are seen as “pure types” that… enable an audience to define categories and differentiate them easily from one another (Durand and Paolella, 2013, p. 4). An attribute or an activity is regarded as core if it is used to define the ‘prototypical’ member of the focal category. For example, a robin is a prototypical member of the category ‘bird’ and having feathers and beak are core attributes of this category. In a similar vein, recent sociological work on categories (Bitektine, 2011; Durand and Paolella, 2013; Hsu and Hannan, 2005; King and Whetten, 2008) distinguished between ‘essential’ organizational activities, asserting that ‘if they were removed the result would be a different kind of organization’ (King and Whetten, 2008, p. 196), and non-essential activities that could be desirable but do not define the organizational category.

Building on research in social categorization we define core activities as central for the organization in the sense that they are essential for categorizing it under a specific label. For example, in our context, a university is expected to engage in teaching and research. These two activities are central for a university and organizations that do not engage in these activities are unlikely to be considered as legitimate members of the university category (Bitektine, 2011; Zuckerman, 1999). Therefore, teaching and research are core activities for universities. On the other hand, we define peripheral activities as secondary, in a sense that they can be useful and desirable, but they are not essential for categorizing the organization under a specific label. For example, in our context, creating social impact via spinoffs was a secondary activity for UK universities in our observation window (1993 to 2007) and not essential for classifying an institution as a university; therefore, the activity was considered as peripheral. We elaborate on this issue in the research-setting section.

Our study argues that both direct and refracted organizational signals (Fombrun and Van Riel, 1997) lead to a reputation for a peripheral activity. Building on economic theory, we expect direct signals of effort (i.e., how much they try) and performance (i.e., how good they are) (Stiglitz, 2000) to communicate information about an underlying, unobservable ability in the peripheral activity. Moreover, drawing on sociological theory, we expect refracted signals by the media (Fombrun and Van Riel, 1997) to influence collective awareness and recognition for the peripheral activity. We argue that this reputation for a peripheral activity is positively related to evaluations for the core activity via the use of heuristics (mental shortcuts) by the organization's audiences (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). Specifically, organizational audiences transfer evaluations from the periphery to the core via two prominent heuristics, namely the representativeness and the availability heuristics. We elaborate on these mechanisms below. We first examine signals of effort and performance and then the refracted signals by the media.

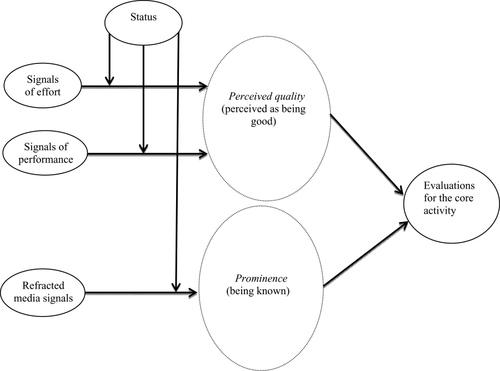

Figure 1 illustrates our study's conceptual framework.

Conceptual framework

HYPOTHESES

Signals of Effort and Perceived Quality

Economic theory has suggested that reputation is formed on the basis of past actions, through which firms signal to stakeholders their true attributes (Clark and Montgomery, 1998). The composition of a firm's action repertoire influences the content of its reputation (Rindova and Fombrun, 1999; Rindova et al., 2007); in simpler terms, what a particular firm does is related to what the firm is known for (Lange et al., 2011). Through strategic investments (namely, configurations of resources and activities), firms signal effort and commitment to a particular area (Ravasi and Phillips, 2011).

Specifically, high frequency of action indicates effort and is associated with the perceived quality dimension of reputation (Basdeo et al., 2006). Frequency of action reduces uncertainty and informational asymmetry between the organization and its audience for the focal activity (Connelly et al., 2011; Stiglitz, 2000). Consequently, frequency of action raises perceptions about quality. For example, in our context, the number of spinoffs that a university generates relates to the perceived quality for impact via spinoffs. This is because a high number of spinoffs signal that a focal university is trying hard to create impact; these signals of effort increase the evaluators' perception that the university is serious about creating impact and their confidence that it will eventually deliver.

Signals of Performance and Perceived Quality

Another important antecedent of perceived quality is the performance of organizational actions (Rindova et al., 2005). Signals of performance in an activity (i.e., being good at it), are a source of information about future performance (Lange et al., 2011). Scholars have examined the impact of past performance on a firm's evaluations on numerous occasions (Deephouse and Carter, 2005; Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Gabbioneta et al., 2007; Rao, 1994). One of the critical findings in the literature is that high-performing organizations exploit their success by sending signals to resource holders, thus attracting their support. High-performance signals travel through networks and help important stakeholders assess the future potential of an organization (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990). Being good at something increases one's reputation for it (perceived quality), as reputation is built on the perceived pattern of success (Fombrun, 1996).

Based on the above principles, we argue that signals of performance for a peripheral activity raise the perceived quality dimension of reputation for this activity. Signals of performance provide an indication of the organization's potential to continue to deliver results in the focal activity in the future. In our context, the performance of a university's spinoffs relates to its perceived quality for impact. High-performing spinoffs signal that a focal university is good at delivering impact (which is distinct from just trying hard). Such signals indicate the potential for the university to continue delivering impact in the future.

The Representativeness Heuristic

We argue that the perceived quality of a peripheral activity (developed by signals of effort and performance as we suggested above) is positively associated with audience evaluations of the core activity via the representativeness heuristic. We know from research on social cognition that evaluators are generally cognitive misers; in other words, they are looking for ways to minimize their cognitive effort (Fiske and Taylor, 1991). People save time and effort while making judgments by using fast-thinking heuristics (Kahneman, 2011), which are timesaving mental shortcuts. Heuristics are usually effective and highly economical ways to decide, but they often lead to systematic and predictable errors (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974).

In the absence of specific information, when people evaluate activity A, they often look for indications in another activity B, which is intuitively associated with (is representative of) A. In a classic example, when patients in a hospital want to speak to a doctor, they are likely to approach a person wearing a white lab coat. This is because wearing a white lab coat is intuitively associated with a person being a doctor (which is often true but not always the case) (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974). Taking intuitive association between two activities as evidence of covariance is the core mechanism of the representativeness heuristic. In our context, social impact could be used as an indicator of good research, as it is intuitive that impact and good research should be associated. In reality, the two attributes do not necessarily co-vary; breakthrough research is often far from having commercial applications, and spinoffs are often based on incremental applied research. Nevertheless, using the representativeness heuristic, research proposal evaluators could take signals of effort and performance in social impact as indicators of good research and raise their research evaluations (Dion et al., 1972; Thorndike, 1920).

Hypothesis 1: Signals of effort related to a peripheral activity are associated with more favourable evaluations of the core activity.

Hypothesis 2: Signals of performance related to a peripheral activity are associated with more favourable evaluations of the core activity.

Refracted Media Signals and Prominence

While signals of effort and performance refer to the perceived quality dimension of reputation, refracted signals by the media drive up the prominence dimension. Prominence refers to ‘the extent to which an organization is widely recognized among stakeholders in its organizational field’ (Rindova et al., 2005, p. 1035). Positive media coverage is likely to both reflect and affect the process of prominence accumulation (Carter and Deephouse, 1999; Deephouse, 2000; Pollock and Rindova, 2003) as journalists constitute an influential audience of critics, who form their own opinions (Rindova et al., 2007). Indeed, prominence is often approximated in the literature by measuring the amount of media coverage (e.g., Dimov et al., 2007; Rindova et al., 2007). Journalists disseminate their opinions to the public and are seen as authoritative sources of information (Deephouse, 2000) and as crucial institutional intermediaries (Pollock and Rindova, 2003). The attention and interpretations that journalists give to organizations become inputs for other stakeholders and affect reputation accumulation among these audiences (Fombrun, 1996; Rindova et al., 2007).

The Availability Heuristic

We argue that building prominence for a peripheral activity via media coverage can increase the evaluations for the core activity by affecting the organization's availability in observers' memories. Availability in memory refers to the relative ease of the retrieval of knowledge about an organization (Fiske and Taylor, 1991; Kahneman, 2011; Tversky and Kahneman, 1973). Increased prominence in peripheral activities makes the organization and its actions more available and familiar in people's memories. Extant literature has suggested that familiarity breeds trust (Gulati, 1995). In turn, trust facilitates further interaction and economic exchange (Lubell, 2007) and can benefit the evaluations of core activities.

Moreover, research on availability as a judgmental heuristic (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974) suggests that the ease with which an example can be called to mind is related to perceptions about how often this event occurs. In a classic application of the availability heuristic, people often overestimate the probability of their plane crashing, being influenced by the elaborate coverage of plane crashes in the media (an attention-catching but rare event) (Kahneman, 2011). Similarly, in our organizational context, a focal university's media-generated prominence for impact via spinoffs would enhance the availability in research-evaluators' memories of examples of pioneering research from this university that led to spinoff firms. In reality, only a small proportion of research projects could lead to spinoff companies, as not all research projects have commercial potential. However, through the enactment of the availability heuristic (i.e., having read spinoff stories about certain universities in the media), research evaluators would overestimate the impact potential of research bids from these universities. Therefore, media-generated prominence regarding social impact via spinoffs would lead to more favourable evaluations for research.

Hypothesis 3: Signals related to a peripheral activity refracted by the media are associated with more favourable evaluations of the core activity.

The Moderating Role of Status

Research in social psychology has suggested that the status of the sender of a message influences the credibility of the message and its acceptability by the receivers (Giffin, 1967; Halperin et al., 1976; Hovland et al., 1953). Applying this principle to organizational research on signalling, we propose that status moderates the relationship between signals for a peripheral activity and the audience evaluations of the core activity.

Status ‘refers to a socially constructed, intersubjectively agreed upon and accepted ordering or ranking of… organizations… in a social system’ (Washington and Zajac, 2005, p. 284). The concept of status is clearly delineated from the concept of reputation (Ertug and Castellucci, 2013; Piazza and Castellucci, 2014; Washington and Zajac, 2005). Status is not necessarily tightly linked to past behaviours (Jensen and Roy, 2008) and can exist independently of economic antecedents (Washington and Zajac, 2005). Status ‘captures differences in social rank… while reputation… captures differences in perceived or actual quality or merit that generate earned, performance-based rewards’ (Washington and Zajac, 2005, p. 283). As Sorenson (2014, p. 64) argues, ‘status stems from position, whereas reputations arise from prior actions'. Moreover, once established, ‘the status ordering is slower to change, when compared with the actor's reputation, in the face of changes in quality or performance’ (Piazza and Castellucci, 2014, p. 293).

Research shows that status increases the credibility of an organization's claims about quality (Fischer and Reuber, 2007; Sine et al., 2003). Credibility refers to the extent to which entity-specific information is believable (Fischer and Reuber, 2007). Messages from high-status organizations are more credible because high-status organizations are perceived as more reliable sources of information than their low-status counterparts. The association between the reliability of the source and the credibility of the message is derived from the Aristotelian notion of ethos (character) of the source and was empirically confirmed by experimental research in social psychology (Giffin, 1967). Based on this principle, we argue that signals related to a peripheral activity coming from organizations of higher status would be perceived as more credible; therefore, the influence of signals related to a peripheral activity on evaluations for the core activity would be greater for high- than for low-status organizations.

In our context, signals from high-status universities about creating social impact via spinoffs are credible, because research evaluators consider these institutions as reliable sources. Credibility intensifies the effect of these signals on building a reputation for impact. In other words, low-status universities signalling strength in creating impact via spinoffs are less believable. Research evaluators would have doubts about whether it is possible for a university of low status to become good at generating spinoffs. These doubts reduce the effect of signals of impact via spinoffs on building a reputation for this activity. Consequently, signals of impact via spinoffs would have a lower effect on evaluations for research.

Hypothesis 4: The relationship between signals related to a peripheral activity and evaluations of the core activity is moderated by status. Specifically, the relationship between signals related to a peripheral activity and evaluations of the core activity is stronger for high-status organizations.

METHODOLOGY

The Empirical Setting: Social Impact via Spinoffs and Research Funding in the UK

Academic spinoffs are new firms created to commercially exploit knowledge, technology, or research results developed within a university (Djokovic and Souitaris, 2008; Lockett and Wright, 2005; Nicolaou and Birley, 2003; O'Shea et al., 2008; Shane, 2004). The emergence of academic spinoffs in the UK is a good context in which to explore whether developing a reputation for a peripheral activity can create spillover effects for the core organizational activity. Creating social impact via academic spinoffs represented a peripheral activity for UK universities during our period of observation (1993−2007) with the core activities being teaching and research (Etzkowitz, 2003).

Creating social impact via spinoffs requires a series of new initiatives and skills, such as technology transfer offices, incentives for faculty, and investment funds, which universities can invest in or opt out from. Social impact and research are also separable as entities. A lot of ‘blue-sky’ research does not have immediately visible social impact, nevertheless it is considered ground-breaking. And many spinoff companies are based on finding a large market for incremental research applications (for example, software or mobile application firms).

Social impact is not present in the formal definition of a university, which is ‘a high-level educational institution where students study for degrees and academic research gets done’ (Oxford English Dictionary, www.oxforddictionaries.com). An institution could be legitimate as a university even if it chose not to embark on spinoff creation. We note that despite the UK government's encouragement to universities to engage in social impact (HM Treasury, 1993), there were also open critiques of university spinoffs as a legitimate university activity. For example, the Swedish Research 2000 Report recommended the withdrawal of universities from the envisaged ‘third mission’ of direct contributions to industry (Benner and Sandstrom, 2000). Instead, the university should return to research and teaching tasks, as traditionally conceptualized. The issues in the Swedish debate were echoed in the critique of academic technology transfer in the USA (Rosenberg and Nelson, 1994; Slaughter and Rhoades, 2004). Some of the critics promoted social arguments; freedom, public accountability, and democratic processes should prevail over short-term economic goals and quest for money (Slaughter and Rhoades, 2004). Others provided economic arguments; academic technology-transfer mechanisms may create unnecessary transaction costs by encapsulating knowledge in patents that might otherwise flow freely to industry (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff, 2000).

In our study, evaluations for research were approximated by research income from competitive funding bids. To understand how research funding evaluators decide, and particularly whether they are sensitive to the issue of social impact of research, we checked the official guidelines offered to evaluators of research grants by the UK research councils and by the European Union (EU). Also, we conducted exploratory interviews with academic colleagues that frequently act as evaluators of research bids for the UK research councils and the EU and individuals in the industry that evaluate university bids for funding. Finally, we (the authors) reflected on our own experiences as evaluators of research bids for two of the UK's leading research councils (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, and Economic and Social Research Council).

Our exploratory interviews and our reflection illustrated that the criterion for evaluation of the research proposals was the quality of the proposed research (potential for success and contribution to knowledge). Potential for impact was a desirable feature (evaluators were exposed to policy and media rhetoric about social impact), but it was not a primary evaluation criterion for research funding during the period of observation. Therefore, the proposed effects of signals of impact on evaluations for research were indirect and reputational.

The Population

To test our hypotheses, we gathered longitudinal data on the population of English and Scottish universities and their spinoff firms. Our panel dataset included a total of 113 universities and 1404 spinoffs covering a period of 15 years (1993−2007). Of these spinoffs, we recorded 287 spinoff exits over the years, leaving us with 1117 live firms by 2007. The most common forms of exit were cases of dissolved, non-trading and dormant firms, receivership, and liquidation.

We collected our data through direct contact with university Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs). We defined spinoffs as companies that involve: ‘(1) the transfer of a core technology from an academic institution into a new company and (2) the founding member(s) may include the inventor academic(s) who may or may not be currently affiliated with the academic institution’ (Nicolaou and Birley, 2003, p. 333). We adopted this strict definition of a university spinoff to ensure that our database only includes established firms with a true and verifiable technology transfer link with the university. We have excluded from the sample population the student and staff start-up firms without university intellectual property links, external start-ups that collaborate with the university, and Knowledge Transfer Partnerships that rent space in university science parks. We have also excluded firms in the prototype stage or those that are not yet registered. Initially, each university supplied us with a historical list of all their spinoff firms based on our definition.

As a first crosscheck, we compared our spinoff population (sourced by asking universities directly) with the well-regarded European spinoff database Proton. The end-of-2006 version of Proton included 609 English and Scottish spinoffs. In contrast, by the end of 2006, our own university-sourced database included 1319 English and Scottish spinoffs and was, therefore, more than double the size of Proton. This fact confirmed that our approach to develop an accurate spinoff database by establishing direct contact with the TTOs was the right approach. Subsequently, we crosschecked our data with a number of spinoff-related reports by the Library House, Ernst and Young, the British Venture Capital Association, the Chemical Leadership Council, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation, the Department of Trade and Industry, and the University Companies Association (UNICO). If Proton or any of the above sources included a firm that was absent from our own directly sourced database, we investigated the case.

As a matter of principle, we checked each firm's website as well as all other secondary sources on the web (for example, press releases) to verify the technology transfer link with the university (i.e., spinoff status) before including it in our database.

Measures

Dependent variable

The UK government funds university research through the so-called dual support mechanism. This includes (a) an annual grant to support the research infrastructure and (b) competitive grants from the Research Councils to fund specific pieces of research (www.rcuk.ac.uk). Since the value of the annual grant is fixed for 5–7 years and is not influenced by the time-varying spinoff activity, we excluded it from this study. Instead, we concentrated on sponsored research funding, a scenario involving universities bidding for research funding and the bids being evaluated by experts (e.g., a scientific committee). UK universities receive competitive research funding from both public and private sources.

In general, university research teams in the UK bid for research funding in three ways: (a) they respond to calls for research on something specific, (b) they apply to open calls for research of their choice, or (c) they approach a research funder directly with a proposal for research (this is more common when approaching industry funders). The evaluators of the proposals can be academics (peers) or practitioners or a mix of the two, and are selected by the funding organizations.

In our study, we measured evaluations of the core activity (research) as the total sponsored research funding. This is the sum of two parts: (1) ‘publicly sponsored research funding’ that includes money provided by seven UK Research Councils, the UK central government and local authorities, health and hospital authorities, and the European Union; and (2) ‘privately sponsored research funding’ that includes income from UK and oversees charities, industry and commerce. We collected the above figures from the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA), which reports annual university income in the UK. Total sponsored research funding was based on the HESA category, ‘research grants and contracts'.

Independent variables

Following past research indicating that organizational audiences interpret the frequency of action as a signal of effort (Basdeo et al., 2006), we used the spinoff portfolio size to measure signals of effort in a peripheral activity. More specifically, portfolio size was measured as the total number of live spinoffs by each university (total births minus deaths) every year in our window of observation. The exact birth and death dates were primarily captured from the Financial Analysis Made Easy (FAME) database. The fact that our panel database begins in 1993 did not pose a serious problem in terms of left censoring, since only 107 firms (about 7 per cent of all spinoffs) were formed in the previous thirty years (1963–92), and five of them had already exited prior to 1993.

We note here that the dependent and most independent variables reported in the main results are measuring flow; the only stock variable is portfolio size. Statistically, it is acceptable to have both stock and flow variables in the same regression model (Maggetti et al., 2013, p. 102) as long as this is optimal theoretically. For instance, Gerring et al. (2005) showed that the stock of democracy affects economic growth (flow) because it is the accumulated sense of democracy that determines the long-term growth of a country. We believe that the stock of existing live spinoffs in a university portfolio (births minus deaths) provides a more accurate picture of how funders consider spinoff portfolios before allocating research money, because deaths are frequent in the spinoff context (Chugh et al., 2011). We therefore chose to keep the stock measurement in the main results. As a robustness test, we changed the measurement of portfolio size from stock to flow (i.e., new spinoffs every year), and the results held.

We measured signals of performance in a peripheral activity by spinoff portfolio performance. This was measured as the total spinoff revenues of all live spinoffs in a university's portfolio at any point in time. Because spinoffs typically only develop significant streams of operating income over long periods of time, we also used total spinoff assets and cumulative number of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) as alternative measures of portfolio performance and conducted robustness checks. These alternatives produced the same results. We collected yearly information on spinoff revenues, assets, and IPO events primarily from the FAME database and, if needed, supplemented it with information from the DueDil database.

We had 53 missing values for spinoff portfolio performance, mostly concentrated in the early years of our panel. This was a relatively minor problem, considering that the total number of observations was 1650. To deal with missing values, we employed the mean substitution method by using the valid values of the variable in the time series as reference for replacing the missing values. Since missing values were predominantly concentrated at the one end of the time series and were not random, we believe that ‘the mean substitution was the best single replacement value’ (Hair et al., 1998, p. 54). To confirm that the imputation process did not alter our results, we also ran the econometric specifications without the imputed values and the results held.

Signals for a peripheral activity refracted by the media were approximated by the variable spinoff portfolio media. This was determined by counting the number of UK press clippings that related to a university and its spinoff firms in a single article. We searched the LexisNexis database for articles with the name of a university and each of its spinoff firms as keywords and marked such articles in our 15-year period. We recorded a total of 8866 articles linked to 1404 spinoffs and their parent universities. Though we could group articles based on their negative or positive tenor (Pollock and Rindova, 2003), an examination of our database showed that there were only 17 articles positioned negatively towards spinoff-related events, mainly associated with bankruptcy-related spinoff exits. We therefore proceeded to measure this independent variable as the total number of media articles on spinoffs for each university every year. As a robustness check, we subtracted a focal university's negative-tenor articles from its positive-tenor articles and rerun the regressions. The results remained the same.

Status

Membership in a sharply bounded category can be an important market signal of quality (Negro et al., 2010) and can render significant status effects. We measured university status by membership in the Russell Group of elite universities, a status-conferring category that is highly influential in UK academia. The Russell Group was intended to lobby government, parliament, and private bodies for financial and other support, and its members have been forming common policies on important initiatives such as the sponsoring and exploitation of intellectual property (Edinburgh University Minutes, 2004). The Russell Group represents universities that are considered the academic elite, with membership being indisputable and difficult to achieve.

Control variables

We aimed to account for alternative drivers of university research income. We measured the cumulative number of awards from the Nobel Foundation as an indicator of academic excellence. We then collected the annual number of publications by each institution in the Thomson Web of Science database (http://thomsonreuters.com) to capture directly the research output of the faculty. In addition, we measured the breadth of submissions in Engineering and Biotech to the national Research Assessment Exercises (RAE) of 1992, 1996, and 2001 (http://www.rae.ac.uk) as an indicator of the underlying scientific research base of universities. We calculated the number of assessment units to which each university submitted results as follows: RAE biotech was the degree of participation in units of assessment 1–17 (1–19 for the 1992 RAE), and RAE engineering was the degree of participation in units of assessment 18–35 (20–37 for the 1992 RAE). These two variables were highly correlated (0.78), and they were therefore averaged into a single RAE score.

We also measured the number of university-assigned patents using data from the European Patent Office (EPO; http://www.epo.org), to capture the intellectual property creation capacity of each university. It was expected that patents would attract competitive research funding from both the government and industry. We finally controlled for the presence of a university hospital by including a dummy variable that took the value of 1 if such a hospital was present. This information was collected from the Association of UK University Hospitals (AUKUH). We expected that university hospitals would attract more sponsored funding for applied research.

We captured annual university rankings as published by the influential Times Higher Education (THE) university guide since 1993. This was consistent with previous research (e.g., Deephouse, 2000; Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Roberts and Dowling, 2002). The ranking of an institution reflects its general perceived quality and collapses the complex information into a single number. It is precisely this synoptic nature of rankings that gives them such a strong impact on evaluators' perceptions (Rindova et al., 2005). We also measured the total media coverage of universities (besides the spinoff-related media coverage) as an indicator of their general prominence. We collected this information from LexisNexis.

We controlled for the Technology Transfer Office structure. This categorical, time-varying variable captured the university support mechanisms for spinoff creation (Clarysse et al., 2005; O'Shea et al., 2005). It took the value of [1] when the TTO was a team within a department of the university (e.g. engineering), [2] when the TTO was a separate unit/department within the university, [3] when the TTO was an independent company (subsidiary), and [4] when the TTO was a publicly listed company. The information was captured via direct contacts with the TTOs themselves.

We finally controlled for university size by taking the total number of full-time students of a university from the HESA database. We expected that bigger universities could attract more resources than smaller ones.

To account for temporal variations in funding, we included year dummies as control variables in all of our models. To control for regional variation, we included regional dummies in all models (nine dummy variables for England plus Scotland). In order to isolate the effects of inflation, all monetary values (i.e., university funding, spinoff performance) were inflated to the current (2013) prices based on information from the UK national statistics authority (Office for National Statistics; ONS).

Analysis

Because we were concerned with count variables that can take large values, hierarchical Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression initially seemed the appropriate statistical method (Gujarati, 2003). However, the Breusch–Pagan (χ2 = 2481.18, p < 0.000) and Wooldridge (F = 111.837, p < 0.000) tests showed that both heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation were present in our panel dataset, thus Generalized Least Squares (GLS) was deemed a more appropriate technique. We performed a Hausman test to decide whether to report random or fixed effects regressions. The Sargan–Hansen statistic was positive and significant (χ2 = 149.612, p < 0.000), indicating that the random effects model was more suitable. As a robustness check, we also ran more restrictive fixed-effects models, controlling for all time-invariant properties of the universities, and our results held.

Endogeneity and, specifically, reverse causality were a concern in our study. The size and the quality of the spinoff portfolio were hypothesized to increase university funding, but it is likely that university funding increases the size and the quality of the spinoff portfolio in the first place. To tackle this issue, all independent and control variables in the GLS models were lagged by two years. These time lags acted as quasi-instruments that allowed for the explanatory variables to develop their impact on the dependent variable through time, thus establishing causation (Judge et al., 2008; Lockett and Wright, 2005; O'Shea et al., 2005; Shipilov et al., 2010).

To account for the possibility of the existence of other unmeasured constructs that had an effect on both the independent and the dependent variables, we instrumented for the characteristics of the spinoff portfolio. The Hausman test indicated that portfolio size, quality, and media were potentially endogenous regressors (χ2 = 28.110, p < 0.000). We therefore used a two-stage least square with instrumental variables (IV-2SLS) regression. To identify instruments, we drew from the known observation that young technology firms tend to cluster regionally (e.g., Buenstorf and Klepper, 2009, 2010). We selected three instrumental variables which were linked to the regional environment and were exogenous to the system, that is, the university and its research income: (a) regional venture capital availability captured from the British Venture Capital Association (BVCA) and measured as the value of venture capital funds raised in a region; (b) local economic growth captured as the change in regional per-capita GDP from the Office of National Statistics; and (c) regional human resources in science and technology, captured from the Eurostat database (http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/eurostat/home/), measured as the percentage of people working in the regional science and technology industries. While there are theoretical reasons to believe that our regional instrumental variables would affect spinoff activity (e.g., Buenstorf et al., 2015; DiGregorio and Shane, 2003; O'Shea et al., 2005; Powers and McDougal, 2005), there are no reasons to believe that they would affect university competitive research income. Competitive research bidding is a national activity, and funders support universities based on their research capabilities and not on the munificence of their location (good research labs often exist in small towns or remote locations). Therefore, the two-stage regression is another way to disentangle the effect of spinoff activity from the effect of other university characteristics. The instruments predicted our three independent variables in first-stage regression estimates. The Hansen J statistic indicated that our set of instruments was orthogonal to the error term (p-value significantly above 0.10), and thus our model was suitable. The results of the instrumental variables models provided support for our hypotheses.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS

Table 1 shows some basic information for the top-20 spinoff-active universities in England and Scotland, year 2007. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics of the variables in our panel dataset. We can see that there is significant variation in the values of the independent variables. For example, the size of the spinoff portfolio ranges from 0 to 74 ventures, depending on the university. The most media-promoted spinoff portfolio was mentioned in a total of 739 articles in a single year, against zero articles for the least promoted portfolios. Similarly, the maximum total revenues produced by a university's spinoff portfolio amounted to £427m in a single year, whereas the mean during all 15 years in the panel was about £5.1m. Total sponsored research funding for each university averaged £18.3m a year. Table 3 shows correlations among the variables. To check for potential issues with multi-collinearity, we conducted Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) tests. The VIF scores were well below the usual warning level of 10 (Gujarati, 2003), and we proceeded with the data analysis normally.

| University | Portfolio live spinoffs | Portfolio spinoff performance (GBP) | Portfolio media coverage | Total sponsored research funding (GBP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridge | 71 | 328,853,577 | 97 | 243,060,000 |

| Oxford | 61 | 227,745,946 | 258 | 285,277,000 |

| Sheffield | 60 | 7,087,623 | 110 | 91,665,000 |

| UCL | 57 | 37,053,061 | 52 | 211,217,000 |

| Manchester | 56 | 23,819,276 | 59 | 175,745,000 |

| Imperial College | 55 | 39,745,868 | 739 | 255,468,000 |

| Edinburgh | 52 | 123,543,399 | 87 | 143,322,000 |

| Strathclyde* | 45 | 20,284,032 | 17 | 35,686,000 |

| Leeds | 35 | 11,674,158 | 25 | 101,207,000 |

| York* | 35 | 8,807,632 | 6 | 50,552,000 |

| Warwick | 35 | 1,020,332 | 5 | 61,665,000 |

| Nottingham | 32 | 11,988,923 | 12 | 83,821,000 |

| Surrey* | 25 | 75,113,902 | 29 | 30,722,000 |

| Newcastle | 23 | 19,216,864 | 13 | 75,401,000 |

| Glasgow | 23 | 14,602,933 | 9 | 116,840,000 |

| Heriot-Watt* | 23 | 4,987,348 | 23 | 15,423,000 |

| Dundee* | 21 | 14,147,259 | 15 | 54,226,000 |

| King's College | 19 | 12,205,096 | 104 | 118,865,000 |

| Southampton | 19 | 42,299,790 | 10 | 84,262,000 |

| Liverpool | 19 | 2,610,024 | 1 | 93,050,000 |

| Total | 766 | 1,026,807,043 | 1,671 | 2,327,474,000 |

- Notes: All institutions belong to the Russell Group except those which are asterisked.

- Spinoff revenues and total funding are at 2013 prices.

| Variables | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total sponsored research funding | 1695 | 18,300,000 | 34,000,000 | 0 | 285,277,000 | – |

| 2 | Nobel awards | 1695 | 0.502 | 2.568 | 0 | 26 | 2.28 |

| 3 | Publications | 1665 | 161.261 | 291.866 | 0 | 2138 | 5.67 |

| 4 | RAE engineering-biotech | 1695 | 35.411 | 35.365 | 0 | 185 | 6.71 |

| 5 | Patents | 1695 | 2.931 | 5.884 | 0 | 50 | 3.32 |

| 6 | University hospital | 1695 | 0.227 | 0.419 | 0 | 1 | 2.95 |

| 7 | Rankings | 1695 | 57.613 | 34.627 | 1 | 123 | 2.55 |

| 8 | Total media coverage | 1695 | 397.808 | 720.321 | 0 | 14945 | 3.85 |

| 9 | TTO structure | 1695 | 0.909 | 1.103 | 0 | 4 | 1.99 |

| 10 | University size | 1695 | 14663.520 | 8359.731 | 145 | 52890 | 1.80 |

| 11 | Russell Group | 1695 | 1.140 | 0.347 | 1 | 2 | 3.92 |

| 12 | Portfolio size | 1695 | 5.110 | 10.252 | 0 | 74 | 4.70 |

| 13 | Portfolio performance | 1695 | 5,115,686 | 28,200,000 | 0 | 427,565,972 | 2.26 |

| 14 | Portfolio media | 1695 | 5.154 | 26.500 | 0 | 739 | 1.99 |

- Note: Spinoff revenues and total funding are at current (2013) prices.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total sponsored research funding | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Nobel awards | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Publications | 0.90 | 0.53 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | RAE engineering-biotech | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Patents | 0.76 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.69 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 6 | University hospital | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 7 | Rankings | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 8 | Total media coverage | 0.73 | 0.53 | 0.65 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 9 | TTO structure | 0.57 | 0.35 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 10 | University size | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.35 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 11 | Russell Group | 0.78 | 0.43 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 12 | Portfolio size | 0.84 | 0.56 | 0.77 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.57 | 1.00 | |||||

| 13 | Portfolio performance | 0.53 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.21 | 0.62 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 1.00 | ||||

| 14 | Portfolio media | 0.62 | 0.30 | 0.56 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 1.00 | |||

- Note: All correlations above 0.10 significant at 0.05.

Table 4 shows the results of the hierarchical GLS regression. Model 1 includes the control variables, most of which were significant with a positive effect on total sponsored research funding. Interestingly, our control variables explain a substantial part of the variance in funding (73 per cent). This indicates that we selected an accurate and comprehensive set of control variables, which account for a number of alternative explanations.

| Variables | Random-effects GLS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

| (Constant) | −0.008 | (0.060) | −0.064 | (0.057) | −0.022 | (0.053) | −0.041 | (0.053) | −0.079 | (0.048) |

| Nobel awards | 0.161a | (0.023) | 0.119a | (0.022) | 0.103a | (0.020) | 0.174a | (0.020) | 0.105a | (0.019) |

| Publications | 0.431a | (0.016) | 0.209a | (0.014) | 0.415a | (0.015) | 0.362a | (0.015) | 0.196a | (0.013) |

| RAE engineering-biotech | 0.130a | (0.026) | 0.082a | (0.022) | 0.161a | (0.025) | 0.139a | (0.024) | 0.111a | (0.020) |

| Patents | 0.039a | (0.011) | −0.010 | (0.009) | 0.048a | (0.011) | 0.053a | (0.010) | 0.007 | (0.008) |

| University hospital | 0.001 | (0.018) | 0.032c | (0.015) | 0.006 | (0.017) | 0.012 | (0.016) | 0.039b | (0.014) |

| Rankings | 0.010 | (0.018) | 0.038c | (0.015) | 0.008 | (0.017) | 0.016 | (0.016) | 0.037b | (0.013) |

| Total media coverage | 0.220a | (0.012) | 0.092a | (0.010) | 0.152a | (0.013) | 0.159a | (0.012) | 0.040a | (0.011) |

| TTO structure | −0.003c | (0.010) | 0.003 | (0.008) | −0.002c | (0.010) | −0.025c | (0.010) | 0.006 | (0.008) |

| University size | −0.008 | (0.015) | −0.010 | (0.012) | −0.009 | (0.014) | −0.001 | (0.013) | −0.004 | (0.011) |

| Russell Group | 0.174a | (0.018) | 0.198a | (0.014) | 0.169a | (0.017) | 0.174a | (0.017) | 0.195a | (0.013) |

| Portfolio size | 0.367a | (0.011) | 0.310a | (0.011) | ||||||

| Portfolio performance | 0.136a | (0.012) | 0.073a | (0.009) | ||||||

| Portfolio media | 0.118a | (0.007) | 0.071a | (0.005) | ||||||

| Year dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Regional dummies | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||

| Wald-chi2 | 6170.98a | 10104.72a | 7289.88a | 7773.07a | 12048.50a | |||||

| N | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | 1650 | |||||

| R2 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.86 | |||||

- a p<0.001,

- b p<0.01,

- c p<0.05,

- †p<0.10.

- Standardized coefficients; standard errors in parentheses.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we found that the size of the spinoff portfolio is related to research income (see model 2) (p < 0.001). Moreover, as predicted in Hypothesis 2, spinoff portfolio performance has a significant impact on research income (see model 3) (p < 0.001). Portfolio media coverage is also associated with research income, as we had predicted in hypothesis 3 (see model 4) (p < 0.001). We combined all three predictors in model 5, and the results confirm all three hypotheses (R2 increases from 73 to 86 per cent).

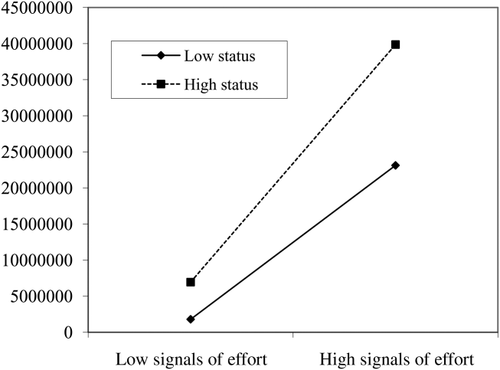

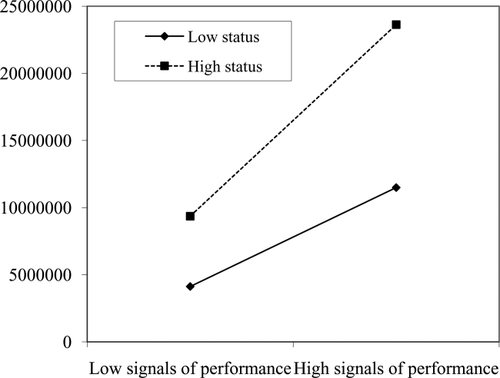

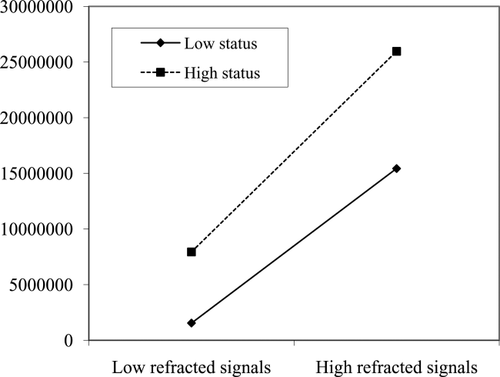

We then tested whether the effects of signals of social impact (measured as spinoff portfolio characteristics) on research income are moderated by the status of the university. The relationships between the characteristics of a university's spinoff portfolio and its research income are positively moderated by membership in the Russell Group. Specifically, the positive effect of the spinoff portfolio size, performance, and media coverage on research income is stronger for high-status (Russell Group) institutions than for low-status institutions (see Table 5). We present these moderation effects graphically in Figures 2-4.

Interaction effect between status and signals of effort

Interaction effect between status and signals of performance

Interaction effect between status and refracted media signals

| Variables | GLS interactions | |

|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | −0.001 | (0.032) |

| Nobel awards | 0.047*** | (0.008) |

| Publications | 0.221*** | (0.013) |

| RAE engineering-biotech | 0.190*** | (0.013) |

| Patents | 0.087*** | (0.009) |

| University hospital | 0.061*** | (0.009) |

| Rankings | 0.009 | (0.008) |

| Total media coverage | 0.052*** | (0.010) |

| TTO structure | 0.027*** | (0.007) |

| University Size | −0.039*** | (0.007) |

| Russell group | 0.117*** | (0.010) |

| Portfolio size | 0.097*** | (0.015) |

| Portfolio performance | 0.012 | (0.024) |

| Portfolio media | 0.062*** | (0.016) |

| Russell** Portfolio size | 0.150*** | (0.014) |

| Russell** Portfolio performance | 0.091*** | (0.024) |

| Russell** Portfolio media | 0.035** | (0.016) |

| Year dummies | Yes | |

| Regional dummies | Yes | |

| N | 1650 | |

| R2 | 0.95 | |

- ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05; †p<0.10.

- Standardized coefficients; standard errors in parentheses.

Further Robustness Checks

In addition to the robustness checks mentioned in the methods section, we conducted further tests to confirm the robustness of our results. To account for the potential effects of outliers, we removed from our sample in separate tests the following elements: (1) 20 Russell Group members, (2) 26 universities with zero spinoffs in their portfolios, (3) the top 10 and bottom 10 of universities by total 2007 revenue, and (4) all panel years except 1993 (starting point), 2000 (middle point), and 2007 (final point). The results were qualitatively similar in all cases. We then (5) disaggregated funding from public and private sectors (the dependent variable), and the results did not change either. We also ran regressions for the sources of funding that we had excluded from the original analysis. Specifically, we (6) analysed the impact of our three spinoff-related predictors on university income from recurrent grants and student fees and, as expected, we did not find significant effects.

We also considered an alternative explanation for our results; it might be that the increase in university research income was due to grants directly linked with its spinoffs and not via reputational benefits. We empirically explored this alternative, but it did not fit the data. We looked at the research grants that spinoffs attracted, but the amounts of money involved were negligible in comparison to the total university research income.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we showed that developing a reputation for a peripheral activity via direct and refracted signals can generate positive spillovers for core organizational activities. We refer to this phenomenon as the peripheral halo effect. We suggest that the mechanisms driving the effect are mental shortcuts (heuristics) used by audiences. In the context of academic entrepreneurship, we found that signals of effort and performance in creating impact via spinoffs, as well as refracted signals generated by the media, influence research income over and above the amount expected from a university's research performance and general reputation. We also found that organizational status amplifies the peripheral halo effect. For high-status organizations (in our context, universities in the Russell Group), the relationship between signals for the peripheral activity (social impact via spinoffs) and evaluations for the core activity (research income) is stronger.1

The study makes three major contributions elaborated below.

The Peripheral Halo Effect

First, we contribute to management theory by providing evidence of the peripheral halo effect. The current literature has suggested that reputation for the core organizational activity can positively impact a new initiative, the so-called halo effect (Crane, 1965; Merton, 1968; Perrow, 1961; Sine et al., 2003; Souitaris and Zerbinati, 2014). We reveal a different (inverse) phenomenon: signalling a reputation for a peripheral activity is associated with audience evaluations for the organization's core activity. By positioning status as an important moderator, we also advance theory on the boundary conditions of the effect.

The peripheral halo effect is important for management, as the impact of peripheral activities on the organization's core business is a key managerial concern. Venturing into peripheral areas of activity is a common organizational endeavour. For example, companies often act to develop new and peripheral product lines; they launch corporate ventures based on good ideas that are off-strategy (i.e., not central to their strategy), and they engage in activities such as CSR initiatives and community engagement. Since peripheral activities entail costs and risk, managers are naturally concerned whether embarking into the periphery is a good idea and specifically whether there are implications for the core-business bottom line. Our findings offer empirical evidence that reputation-developing signals related to a peripheral activity can actually positively influence evaluations for the core activity. This peripheral halo effect, which applies to a variety of organizational contexts, could be used as a strategically managed tool to generate growth in the firm's core business.

Our conceptualisation of the peripheral halo effect contributes to the literature on organizational reputation. Scholars have called for research to disentangle organizational reputation among different domains of activity and understand how reputation for one aspect affects outcomes for another. For example, Lange et al. (2011) suggested that, ‘among the other possibilities to explore is the idea that a high degree of “being known for something” may contribute to increases in the “being known [in general]” dimension of reputation’ (p. 168). Our study takes a step in this direction by showing that reputation for one domain of activity (a peripheral activity) is related to evaluations for another domain (the core activity).

Since our results show the transferability of reputation across domains of activity, they have implications for an interesting debate in the reputation literature. In a recent study, Dimov and Milanov (2010) found that, contrary to their expectations, venture capitalists' core reputation can hamper their ability to syndicate for novel projects. In simpler terms, reputation for something could actually make it harder to diversify into something new. We believe that the transferability of reputation across domains of activity could depend on the nature of the domains (see also Wry et al., 2014). In situations in which the audience perceives that the new domain of activity is almost in antithesis of the old one (i.e., actors have to unlearn what they are good at), reputation might not be transferable or even have a negative effect. However, in situations in which no such perceived conflict exists between the domains of activity (e.g., good research and social impact are not in antithesis), reputation can transfer between them. Future research would be needed to confirm this thesis. Moreover, a good avenue for future research would be the examination of whether the peripheral halo effect might be more or less prevalent than the transfer of reputation from the core to the periphery. We generally believe that finding the nuances of the transferability of reputation across domains of activity is a fruitful area for research in the reputation literature.

Social categorization is a dynamic process and therefore activities could fluctuate over time between the periphery and the core. For example, an emergent activity can be peripheral for some time but eventually it might become part of the core (e.g., a computer company starts developing music players as a peripheral activity but, subsequently, music-player development becomes part of its core activities). In our context, social impact by universities via spinoffs could be such a case; that is, an emerging activity which was peripheral during our observation period but has potential to become part of a university's core activities someday. Studying the peripheral halo effect dynamically, as an emerging activity that might move over time from the periphery towards the core, is an interesting and challenging future research direction.

Our findings also have implications for signalling theory, as they illustrate the resource benefits of signals as by-products of organizational action. In the university context, it is not clear whether spinoff portfolios were created as signalling devices. In fact, it is likely that, at least in the beginning, they were created in the hope of generating financial benefits from equity positions (Bray and Lee, 2000; Feldman et al., 2002). In the words of one TTO manager that we interviewed, ‘what we are trying to do with spinoffs is get the money from the equity sale'. Signalling theory states that parties may send a variety of signals without even being aware that they are signalling (Spence, 2002). Signals that are not intentional or that were not the primary objective of the action (by-products of action), have been relatively ignored in signalling theory (Connelly et al., 2011; Janney and Folta, 2006). Our study shows the often-unanticipated positive benefits of such signals.

Reputation and Status

Our second contribution is to research on the interdependency between reputation and status. We show that reputation-building signals are interpreted differently depending on the status of the sender. Specifically, reputation-building signals from high-status senders are more credible and consequently have a higher impact on audience evaluations.

Recently, scholars have attempted to investigate the concurrent role of status and reputation on organizational outcomes both independently (Dimov and Milanov, 2010; Washington and Zajac, 2005) and sequentially (Jensen and Roy, 2008). Washington and Zajac (2005) showed that reputation and status had independent effects on the selection of basketball teams to participate in the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) postseason tournament. In a different study, Jensen and Roy (2008) argued that status and reputation are used sequentially when choosing exchange partners, with organizations first using status to screen prospective firms and then using reputation to select a partner within a particular status bracket.

However, an integrated understanding of the potential role of status and reputation in organizational phenomena is still missing (Ertug and Castellucci, 2013). In this study, we examine the interdependent effects of status and reputation on audience evaluations. We find that high status moderates the relationship between reputation-building signals for a peripheral activity and evaluations for the core activity. Specifically, signals from high-status senders have a stronger effect on audience evaluations than signals from low-status senders. Therefore, we show that signals building a reputation for a peripheral activity are interpreted differently and have a different effect on outcomes depending on the status of the sender. This suggests that high-status organizations are likely to benefit much more from building a reputation for their peripheral activities. They may have a greater incentive to engage in such activities as a result. On the contrary, low-status organizations would need to try much harder to increase their benefits from the peripheral halo effect.

Academic Entrepreneurship

A third and equally important contribution of our work is within the literature on academic entrepreneurship (Djokovic and Souitaris, 2008; O'Shea et al., 2008; Rothaermel et al., 2007). We illustrate that characteristics of the university spinoff portfolio are associated with university research income. Our findings are important for the academic entrepreneurship literature because they respond to the enduring gap in our knowledge regarding whether entrepreneurial universities benefit from spinoff activities (Shane, 2004). Our study joins and extends an emerging stream of research which redirects the attention of the literature from how universities can help spinoffs to how spinoffs can affect academic indicators such as research productivity (Buenstorf, 2009; Lowe and Gonzales-Brambila, 2007; Toole and Czarnitzki, 2010), faculty learning and creativity (Perkmann and Walsh, 2009), and faculty retention (Nicolaou and Souitaris, 2013). To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that spinoff activity contributes financially to universities by raising research income over and above the amount expected by university scientific eminence and general reputation.

Apart from establishing statistical significance, we also evaluated the economic significance of our findings. We noted that the average annual competitive research income of a university was £18,300,000 (2013 values). From our basic model, we calculated that: (1) one additional spinoff in the university's portfolio increases university annual income by £1,028,292 (5.62 per cent of the average income); (2) one additional million pounds of spinoff revenue (for the whole live portfolio) increases university research income by £88,014 (0.48 per cent of the average income); and (3) one additional media hit increases research income by £91,094 (0.50 per cent of the average income). The combined increase in research income (£1,207,400 in 2013 values) for the three characteristics of the spinoff portfolio is 6.60 per cent of the mean income.

We also estimated that: (1) an increase of one standard deviation in portfolio size (10.25 spinoffs) raises income by £10,540,000 (57.60 per cent increase over the mean); (2) an increase of one standard deviation in portfolio quality (£28,200,000) raises research income by £2,482,000 (13.56 per cent increase over the mean); and (3) an increase of one standard deviation in portfolio media (26.5 articles) increases research income by £2,414,000 (13.19 per cent increase over the mean). The total increase in research income (£15,436,000 in 2013 prices) for one standard deviation increase across all three characteristics of the spinoff portfolio is 84.35 per cent of the mean income.

Moreover, we compared the increase in research income by a single spinoff firm to the yearly average university income from sales of spinoff shares and the yearly average income from licensing. From the Business and Community Interaction survey (HEFCE, 2008), we found that, for 2006–07, the 113 universities in England and Scotland made on average £154,814 (in current prices) from sales of spinoff shares and £339,265 (in current prices) from licensing. Instead, from our model, a single spinoff can indirectly raise research income by £1,028,292 in current prices.

Based on the results as a whole, we concluded that spinoff activity is, as expected, not the main driver of research income. It is a peripheral activity that explains about 13 per cent of the variance in university competitive research funding. However, the figures above showed that the effects of spinoff-portfolio characteristics on research income are not only statistically but also economically significant. For a peripheral activity, spinoffs have a substantial and meaningful economic effect on research income, over and above the effect of research performance and general reputation.

This evidence for the impact of academic spinoffs on university income is particularly important for university managers. Considering the amount of money and effort put into spinoffs by universities worldwide, it is crucial for university leaders to arrive at true estimates of the economic returns of these ventures. Given that direct returns from university equity positions in spinoffs have proved negligible (Bok, 2003; Shane, 2004; Slaughter and Leslie, 1997), the reputation perspective allowed us to demonstrate the indirect association of spinoffs with university income. We advise university executives to concentrate more on demonstrating the social impact by building a sizeable, well-performing and well-publicized spinoff portfolio, than negotiating hard on the equity split.

The findings also have implications for government officials who design innovation policies. We showed that the institutionalization of academic spinoffs led public and private resource holders to fund those universities that signalled their compliance with the new social mandate. Therefore, policy makers could engineer and maintain healthy social pressure to universities to contribute directly to society via commercialization of academic research. In summary, policy rhetoric guides the behaviour of research funders and indirectly incentivizes universities to engage in technology transfer.

An interesting theme for future research in academic entrepreneurship would be to examine the impact of spinoff companies on other intangible university assets. For instance, it might be worthwhile to examine the impact of spinoffs on universities' general reputations (the rankings) and on the recruitment of faculty members and PhD researchers. Discussions with Technology Transfer Officers during our study revealed that there have been cases in which faculty teams moved to another university because they found appealing the prospect of working on spinoff-related projects.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. Following previous research, we infer the unobservable effects of reputation by studying the direct effects of observable signals, namely organizational actions, performance, and media coverage on performance outcomes (e.g., Rao, 1994; Stuart, 2000). Direct measurement of reputation for impact was not possible because of the lack of original and contemporary audience evaluations of the universities' ability to spinoff. While this is a methodological limitation (Rindova et al., 2005), signals and media endorsement are commonly used in the literature as proxies of reputation (see, e.g., Dimov et al., 2007).