Colonoscopy findings after increasing two-stool faecal immunochemical test (FIT) cut-off: Cross-sectional analysis of the SCREESCO randomized trial

Abstract

Background

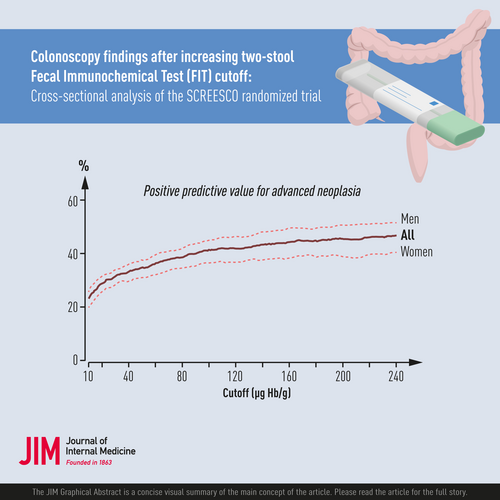

We determined the impact of an increased two-stool faecal immunochemical test (FIT) cut-off on colonoscopy positivity and relative sensitivity and specificity in the randomized controlled screening trial screening of Swedish colons conducted in Sweden.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of participants in the FIT arm that performed FIT between March 2014 and 2020 within the study registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02078804, who had a faecal haemoglobin concentration of at least 10 µg/g in at least one of two stool samples and who underwent a colonoscopy (n = 3841). For each increase in cut-off, we computed the positive predictive value (PPV), numbers needed to scope (NNS), sensitivity and specificity for finding colorectal cancer (CRC) and advanced neoplasia (AN; advanced adenoma or CRC) relative to cut-off 10 µg/g.

Results

The PPV for AN increased from 23.0% (95% confidence intervals [CI]: 22.3%–23.6%) at cut-off 10 µg/g to 28.8% (95% CI: 27.8%–29.7%) and 33.1% (95% CI: 31.9%–34.4%) at cut-offs 20 and 40 µg/g, respectively, whereas the NNS to find a CRC correspondingly decreased from 41 to 27 and 19. The PPV for AN was higher in men than women at each cut-off, for example 31.5% (95% CI: 30.1%–32.8%) in men and 25.6% (95% CI: 24.3%–27.0%) in women at 20 µg/g. The relative sensitivity and relative specificity were similar in men and women at each cut-off.

Conclusion

A low cut-off of around 20–40 µg/g allows detection and removal of many AN compared to 10 µg/g while reducing the number of colonoscopies in both men and women.

Graphical Abstract

Abbreviations

-

- AN

-

- advanced neoplasia

-

- CRC

-

- colorectal cancer

-

- FIT

-

- faecal immunochemical test

-

- SSP

-

- sessile serrated polyp

Introduction

An acceptable balance between benefit and harm in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening is achieved by selecting a threshold for a positive faecal immunochemical test (FIT) result that enables detection and removal of as many significant lesions as possible but is balanced against the number of unnecessary colonoscopies. The optimal faecal haemoglobin (Hb) cut-off for a positive FIT result is still debated [1-4]. Clinically relevant cut-offs have been proposed in the range between 9 and 25 µg Hb/g faeces [5]. One study suggested 9 µg/g (45 ng/mL; using the approximation 1 µg/g ≈ 5 ng/mL), where 24 colonoscopies were required to detect one CRC. Higher cut-offs may be optimal, for example 16 or 25 µg/g, when fewer colonoscopies are required due to, for example restrictions on colonoscopy capacity or costs [1]. In Scotland, the cut-off is currently 80 µg/g [6], and in the Netherlands, the cut-off was increased from 15 to 47 µg/g due to capacity [7]. The performance of FIT screening may vary between men and women [8-10], and sex-specific cut-offs and screening age ranges have been proposed to address potential inequalities between men and women [11], such a wider age range of screening in men and a lower cut-off for a positive test in women [12]. The cut-offs in the Swedish screening program of Stockholm–Gotland were set to 80 µg/g for men and 40 µg/g for women to obtain comparable age-dependent FIT positivity rates [13].

SCREESCO (screening of Swedish colons) is a nationwide randomized clinical trial (RCT) conducted in Sweden that includes a once only primary colonoscopy screening arm (PCOL) and a FIT screening arm using two stool samples instead of one and an unusually low cut-off of 10 µg/g.

In this study, we took advantage of the low cut-off to study what the consequences would be of using higher cut-offs in terms of missed findings and number of negative colonoscopies. We also explored the possibility of differential implications for men and women to test the hypothesis that the sensitivity with increasing cut-off would decrease less for men than women.

Materials and methods

Study population

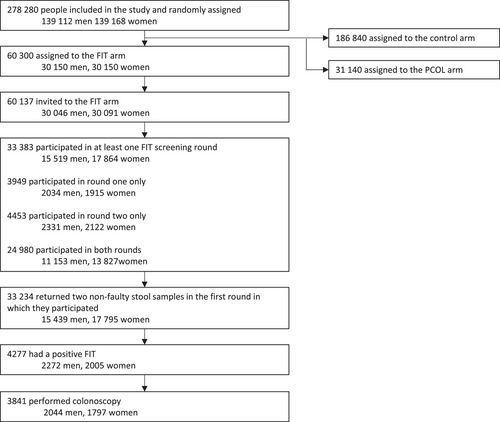

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of participants in the randomized controlled trial SCREESCO. It was performed in 18 of 21 regions of Sweden where screening for CRC was not previously being offered as previously described [14, 15]. Sixty-year-old men and women born 1954–1958 without a previous diagnosis of colorectal or anal cancer or participation in the NordICC trial [16] were randomized to one of three arms: (PCOL arm), invitations to two rounds of high-sensitive FIT using a kit for stool samples two years apart (FIT × 2 arm), or no intervention (control arm).

Individuals assigned to the FIT arm were sent kits for faecal samples. A quantitative FIT using two faecal samples with separate kits for each faecal sample was offered in each screening round. The invitees were instructed to take samples from two different bowel movements, preferably not on the same day. One central laboratory performed all FIT analyses using a single OC-Sensor Diana automated analyser. A faecal Hb concentration of at least 10 µg Hb/g faeces in at least one of the two stool samples defined the cut-off for positivity, triggering an invitation to a colonoscopy. If both stool samples were faulty or if one was faulty and the other negative, a new a kit for stool samples was sent. Individuals with a faecal Hb concentration below 10 µg/g in both stool samples did not undergo colonoscopy. All individuals in the FIT arm, except those requiring colonoscopy surveillance after adenoma removal or after a CRC diagnosis, were offered a repeat FIT after 2 years, irrespective of participation in the first FIT screening round or if the result was negative or positive, and were sent kits for faecal samples using the same procedure as in the first screening round. The FIT positivity after two pooled rounds of screening in SCREESCO was 19.4% [14]. Prior to colonoscopy, individuals filled out a health questionnaire, including questions about medication use and lifestyle (smoking habits in particular).

The Ethics Committee at Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden) approved the study (2012/2058-31/3). Individuals performed informed consent by returning an FIT. This study has trial number NCT02078804 and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/nct02078804.

Data

Individuals recruited in the FIT arm were included in the present study if they returned two non-faulty stool samples at their first attempt in the first round in which they participated (defined as having returned at least one stool sample), had a faecal Hb concentration of at least 10 µg/g in at least one of the two stool samples, and performed at least one colonoscopy within SCREESCO in the corresponding round. Non-responders and those with a faecal Hb concentration below 10 µg/g in both stool samples were excluded from this study.

We only considered colonoscopy findings from the first screening round in which the individual participated in FIT screening, and any potential results from a colonoscopy performed in the second round were not considered if the individual participated in the first. Some may have had multiple colonoscopies during the screening round, for example, due to incomplete colonoscopy. All findings from incomplete colonoscopies prior to the final colonoscopy within the screening round were included as well as additional details of findings detected at a colonoscopy undergone during subsequent examinations.

We considered several binary outcomes regarding the findings at colonoscopy (positive and negative): any finding (any adenoma or CRC), advanced neoplasia (AN) (advanced adenoma or CRC), CRC and having at least one advanced sessile serrated polyp (SSP). Adenomas were considered advanced adenoma if having a diameter ≥10 mm or contained high-grade dysplasia, or having a villous component and SSPs were considered advanced if being at least 10 mm or containing dysplasia. In each case, the colonoscopy was defined as negative if there were no such findings.

Statistical analysis

We reported faecal Hb concentration as the greater of the two stool samples. We assessed the impact of increasing the cut-off from 10 to 20, 40, 60, 80, 120 or 160 µg/g on the number of colonoscopies, changes in positive predictive value (PPV; colonoscopy positivity), numbers needed to scope (NNS; equal to 1/PPV) and in sensitivity and specificity. A FIT was considered false negative at an alternative cut-off if the colonoscopy was positive for the outcome of interest but the greater of the two tests was below the cut-off, and it was considered false positive if the colonoscopy was negative, but the greater FIT result was above the cut-off. Note that the sensitivity and the specificity are relative to findings at 10 µg/g and do not represent absolute risks.

For each outcome, the relative sensitivity was estimated by the proportion of individuals with a positive test result among all individuals with a positive colonoscopy, and the relative specificity was estimated by the proportion of individuals with negative test results among all with a negative colonoscopy. The PPV, equal to the colonoscopy positivity, was estimated by the proportion of positive colonoscopies among all colonoscopies in those with faecal Hb concentration above the cut-off, and the NNS was estimated by 1/positivity. Note that in FIT participants, (absolute) sensitivity at a specific cut-off is equal to the (absolute) sensitivity at cut-off 10 µg/g multiplied with the relative sensitivity, and (absolute) 1-specificity is equal to (absolute) 1-specificity at cut-off 10 µg/g multiplied with 1-relative specificity. Analyses were stratified by sex. We reported 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the PPV, and the relative sensitivity and specificity.

For each outcome, binomial regression models with log-link were used to estimate the risk ratios (RR) comparing men versus women (reference) of the PPV, and of relative sensitivity, and 1-relative specificity. We reported 95% CIs and p-values under the null hypothesis of no sex differences in PPV at each cut-off, and under the null hypothesis of no sex differences in relative sensitivity and 1- relative specificity, respectively, due to an increase in FIT cut-off.

The analyses were performed using R (4.1.3).

Role of the funding source

Financial support was provided by the Swedish regions, Regional Cancer Centre Mellansverige, the Swedish Cancer Society (2018/595), the Aleris Research and Development Fund and Eiken Chemical. Financial support was also provided through the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, and by the Swedish.

Society of Medicine (Ihre Foundation, SLS-961166). The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. MW, JE, LH and AF had access to the included study data. All authors agreed with the final decision to submit for publication.

Results

Patient flow chart and baseline characteristics

In the SCREESCO study, 60,300 were randomized to the FIT arm (50% men and 50% women), and 33,383 (55.5%) participated in at least one FIT screening round out of 60,137 invited (Fig. 1). Almost all participants (99.6%) returned two non-faulty stool samples in the first round in which they participated, and 4277 (12.9%) of these had a positive FIT result. Most of these underwent a colonoscopy (n = 3841; 89.8%), and most colonoscopies (95.9%) were complete at the first attempt, and 40 (76.9%) of the 52 participants with prior incomplete colonoscopies had an additional colonoscopy because of inadequate bowel cleansing. Median age at colonoscopy was 61 years (IQR: 60–61) and similar for men and women (Table 1). The proportion of daily cigarette smokers was lower in men (12.5%) compared to women (16.4%).

| All | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Total number of participants | 3841 | (100) | 2044 | (100) | 1797 | (100) |

| Age at colonoscopy | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 61 (60–61) | 61 (61–61) | 61 (60–61) | |||

| 59 | 2 | (0.1) | 1 | (0) | 1 | (0.1) |

| 60 | 1040 | (27.1) | 509 | (24.9) | 531 | (29.5) |

| 61 | 2207 | (57.5) | 1185 | (58) | 1022 | (56.9) |

| 62 | 592 | (15.4) | 349 | (17.1) | 243 | (13.5) |

| Daily cigarette smoker | ||||||

| Yes | 549 | (14.3) | 255 | (12.5) | 294 | (16.4) |

| No | 2773 | (72.2) | 1529 | (74.8) | 1244 | (69.2) |

| Previous smoker | 490 | (12.8) | 245 | (12) | 245 | (13.6) |

| Unknown | 29 | (0.8) | 15 | (0.7) | 14 | (0.8) |

| Calendar period of FIT | ||||||

| June 2014–April 2016 | 1829 | (47.6) | 971 | (47.5) | 858 | (47.7) |

| May 2016–April 2018 | 1782 | (46.4) | 933 | (45.6) | 849 | (47.2) |

| May 2018–March 2020 | 230 | (6) | 140 | (6.8) | 90 | (5) |

| Faecal Hb concentrationa (µg Hb/g faeces) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 26.8 (14.8–68.2) | 27.6 (14.6–74.4) | 26.2 (14.8–62.8) | |||

| 10–20 | 1522 | (39.6) | 798 | (39) | 724 | (40.3) |

| 20–40 | 891 | (23.2) | 451 | (22.1) | 440 | (24.5) |

| 40–60 | 369 | (9.6) | 199 | (9.7) | 170 | (9.5) |

| 60–80 | 198 | (5.2) | 109 | (5.3) | 89 | (5) |

| 80–120 | 208 | (5.4) | 131 | (6.4) | 77 | (4.3) |

| 120–160 | 112 | (2.9) | 63 | (3.1) | 49 | (2.7) |

| 160+ | 541 | (14.1) | 293 | (14.3) | 248 | (13.8) |

| Health care region at colonoscopy | ||||||

| North | 405 | (10.5) | 222 | (10.9) | 183 | (10.2) |

| South–east | 1157 | (30.1) | 620 | (30.3) | 537 | (29.9) |

| South | 498 | (13) | 262 | (12.8) | 236 | (13.1) |

| West | 1029 | (26.8) | 546 | (26.7) | 483 | (26.9) |

| Central | 752 | (19.6) | 394 | (19.3) | 358 | (19.9) |

| Colonoscopy findings | ||||||

| No adenoma or colorectal cancer | 2208 | (57.5) | 1051 | (51.4) | 1157 | (64.4) |

| Any findingb | 1633 | (42.5) | 993 | (48.6) | 640 | (35.6) |

| Nonadvanced adenoma | 751 | (19.6) | 469 | (22.9) | 282 | (15.7) |

| Advanced neoplasia | 882 | (22.9) | 524 | (25.6) | 358 | (19.9) |

| Advanced adenoma | 788 | (20.5) | 470 | (23) | 318 | (17.7) |

| Colorectal cancer | 94 | (2.4) | 54 | (2.6) | 40 | (2.2) |

| Sessile serrated polyp of at least 10 mm in diameter | 155 | (4) | 77 | (3.8) | 78 | (4.3) |

- Abbreviation: FIT, faecal immunochemical test.

- a Maximum of two stool samples.

- b Defined as the most advanced finding among all findings for an individual.

Faecal haemoglobin concentration and colonoscopy findings

Both FITs were at least 10 µg/g in 1304 (33.9%) individuals, 689 (33.7%) in men and 615 (34.2%) in women. Median Hb concentration of the maximum of the two FIT stool samples was 26.8 µg/g (IQR: 14.8–68.4 µg/g), and this was similar in men (27.8 µg/g; IQR: 14.6–75.0 µg/g) and in women (26.2 µg/g; IQR: 14.8–62.2 µg/g) (Table 1). A total of 751 (19.6%) individuals had nonadvanced adenoma, 882 (22.9%) had AN, 788 (20.5%) had advanced adenoma, and 94 (2.4%) had CRC as worst finding. Men had AN more often than women (25.6% in men vs. 19.9% in women). There were 155 (4.0%) participants with at least one advanced SSP.

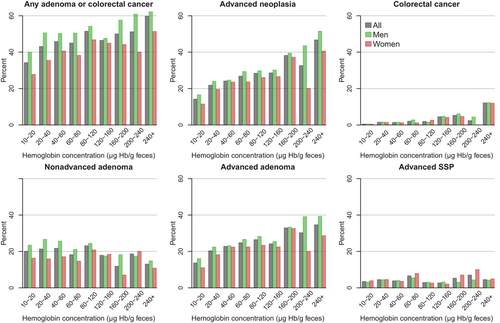

The risk of any finding except advanced SSP increased with increasing Hb concentration, for example risk of AN increased from 14.1% among those with a Hb concentration 10–20 µg/g to 44.4% among those with Hb concentration above 160 µg/g, and the risk of CRC increased correspondingly from 0.5% to 10.4% and the risk of advanced adenoma increased from 13.7% to 34.0% (Fig. 2, Table S1).

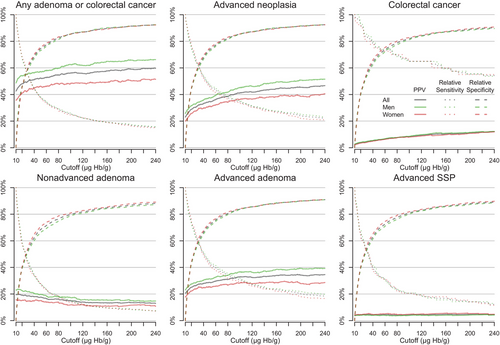

Positive predictive value and numbers needed to scope at different cut-offs

In general, the number of colonoscopies decreased rapidly when increasing the cut-off for the maximum of the two stool samples, especially from 10 to 20, 40 and 80 µg/g where the number of colonoscopies decreased to 2319 (60.4%), 1428 (37.2%) and 861 (22.4%), respectively (Table 2). Simultaneously, the PPV increased with increasing FIT cut-off for each type of colonoscopy finding except advanced SSP (Fig. 3, Table 2, Tables S2 and S3). For example, the PPV for AN increased from 23.0% (95% CI: 22.3%–23.6%) to 28.8% (95% CI: 27.8–29.7), respectively, when increasing the cut-off from 10 to 20 µg/g (Fig. 3, Table 2), and for CRC the PPV increased from 2.4% (95% CI: 2.2%–2.7%) to 3.8% (95% CI: 3.4%–4.1%) at the same cut-offs. The NNS to find one CRC at FIT cut-off 10 µg/g was 40.9, and it decreased to 26.7 at FIT cut-off 20 µg/g.

| Outcome | Cut-off (µg/g) | Colonoscopies | (%) | Findings | PPV | (95% CI) | NNS | Relative Sensitivity | (95% CI) | Relative Specificity | (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any adenoma or colorectal cancer | 10 | 3841 | (100.0) | 1633 | 42.5 | (41.7–43.3) | 2.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 20 | 2319 | (60.4) | 1113 | 48.0 | (47.0–49.0) | 2.1 | 68.2 | (67.0–69.3) | 45.4 | (44.3–46.4) | ||

| 40 | 1428 | (37.2) | 729 | 51.1 | (49.7–52.4) | 2.0 | 44.6 | (43.4–45.9) | 68.3 | (67.4–69.3) | ||

| 60 | 1059 | (27.6) | 560 | 52.9 | (51.3–54.4) | 1.9 | 34.3 | (33.1–35.5) | 77.4 | (76.5–78.3) | ||

| 80 | 861 | (22.4) | 471 | 54.7 | (53.0–56.4) | 1.8 | 28.8 | (27.7–30.0) | 82.3 | (81.5–83.1) | ||

| 120 | 653 | (17.0) | 364 | 55.7 | (53.8–57.7) | 1.8 | 22.3 | (21.3–23.3) | 86.9 | (86.2–87.6) | ||

| 160 | 541 | (14.1) | 312 | 57.7 | (55.5–59.8) | 1.7 | 19.1 | (18.1–20.1) | 89.6 | (89.0–90.3) | ||

| Advanced neoplasia | 10 | 3841 | (100.0) | 882 | 23.0 | (22.3–23.6) | 4.4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 20 | 2319 | (60.4) | 667 | 28.8 | (27.8–29.7) | 3.5 | 75.6 | (74.2–77.1) | 44.2 | (43.3–45.1) | ||

| 40 | 1428 | (37.2) | 473 | 33.1 | (31.9–34.4) | 3.0 | 53.6 | (51.9–55.3) | 67.7 | (66.9–68.6) | ||

| 60 | 1059 | (27.6) | 384 | 36.3 | (34.8–37.7) | 2.8 | 43.5 | (41.9–45.2) | 77.2 | (76.4–78.0) | ||

| 80 | 861 | (22.4) | 331 | 38.4 | (36.8–40.1) | 2.6 | 37.5 | (35.9–39.2) | 82.1 | (81.4–82.8) | ||

| 120 | 653 | (17.0) | 272 | 41.7 | (39.7–43.6) | 2.4 | 30.8 | (29.3–32.4) | 87.1 | (86.5–87.7) | ||

| 160 | 541 | (14.1) | 240 | 44.4 | (42.2–46.5) | 2.3 | 27.2 | (25.7–28.7) | 89.8 | (89.3–90.4) | ||

| Colorectal cancer | 10 | 3841 | (100.0) | 94 | 2.4 | (2.2–2.7) | 40.9 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 20 | 2319 | (60.4) | 87 | 3.8 | (3.4–4.1) | 26.7 | 92.6 | (89.8–95.3) | 40.4 | (39.6–41.2) | ||

| 40 | 1428 | (37.2) | 74 | 5.2 | (4.6–5.8) | 19.3 | 78.7 | (74.5–82.9) | 63.9 | (63.1–64.6) | ||

| 60 | 1059 | (27.6) | 69 | 6.5 | (5.8–7.3) | 15.3 | 73.4 | (68.8–78.0) | 73.6 | (72.9–74.3) | ||

| 80 | 861 | (22.4) | 65 | 7.5 | (6.6–8.4) | 13.2 | 69.1 | (64.4–73.9) | 78.8 | (78.1–79.4) | ||

| 120 | 653 | (17.0) | 61 | 9.3 | (8.2–10.5) | 10.7 | 64.9 | (60.0–69.8) | 84.2 | (83.6–84.8) | ||

| 160 | 541 | (14.1) | 56 | 10.4 | (9.0–11.7) | 9.7 | 59.6 | (54.5–64.6) | 87.1 | (86.5–87.6) | ||

| Advanced SSP | 10 | 3841 | (100.0) | 155 | 4.0 | (3.7–4.4) | 24.8 | 100.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 20 | 2319 | (60.4) | 102 | 4.4 | (4.0–4.8) | 22.7 | 65.8 | (62.0–69.6) | 39.9 | (39.0–40.7) | ||

| 40 | 1428 | (37.2) | 62 | 4.3 | (3.8–4.9) | 23.0 | 40.0 | (36.1–43.9) | 62.9 | (62.1–63.7) | ||

| 60 | 1059 | (27.6) | 48 | 4.5 | (3.9–5.2) | 22.1 | 31.0 | (27.3–34.7) | 72.6 | (71.8–73.3) | ||

| 80 | 861 | (22.4) | 35 | 4.1 | (3.4–4.7) | 24.6 | 22.6 | (19.2–25.9) | 77.6 | (76.9–78.3) | ||

| 120 | 653 | (17.0) | 29 | 4.4 | (3.6–5.2) | 22.5 | 18.7 | (15.6–21.8) | 83.1 | (82.5–83.7) | ||

| 160 | 541 | (14.1) | 26 | 4.8 | (3.9–5.7) | 20.8 | 16.8 | (13.8–19.8) | 86.0 | (85.5–86.6) | ||

- Abbreviations: CI, Confidence Interval; NNS, numbers needed to scope; SSP, sessile serrated polyp.

At higher cut-offs, the PPV increased further with similar impact on NNS. For example, the PPV for AN was 33.1% (95% CI: 31.9%–34.4%) at cut-off 40 µg/g and 38.4% (95% CI: 36.8%–40.1%) at cut-off 80 µg/g, and for CRC the PPV was 5.2% (95% CI: 4.6%–5.8%) and 7.5% (95% CI: 6.6%–8.4%) at the same cut-offs (Table 2).

Consequences of increased FIT cut-off on relative sensitivity and specificity

The relative (compared to 10 µg/g) sensitivity generally decreased slowly, and the relative specificity increased rapidly with increasing FIT cut-off for the maximum of the two stool samples for each type of colonoscopy finding (Table 2, Fig. 3, Tables S2 and S3). For example, at cut-off 20 µg/g the relative sensitivity was 75.6.4% (95% CI: 74.2%–77.1%), and the relative specificity was 44.2.8% (95% CI: 43.3%–45.1%) for AN, whereas, for CRC, these were 92.6% (95% CI: 89.8%–95.3%) and 40.4% (95% CI: 39.6%–41.2%) correspondingly. For AN, the relative sensitivity decreased to 53.6% (95% CI: 51.9%–55.3%), and the relative specificity increased to 67.7% (95% CI: 66.9%–68.6%) when further increasing the cut-off to 40 µg/g, and similar changes applied to other findings. The relative sensitivity for having at least one advanced SSP decreased at similar rate as the corresponding relative specificity increased.

Consequences for men and women

The number of colonoscopies decreased similarly in men and women when increasing the cut-off except for cut-offs 40–80 µg/g where the decrease was somewhat stronger for women, and the PPV was generally higher in men than in women for each type of finding except advanced SSP at all cut-offs (Fig. 3, Tables S2 and S3). For example, at 20 µg/g, the PPV for AN was 31.5% (95% CI: 30.1%–32.8%) in men and 25.6% (95% CI: 24.3%–27.0%) in women (RR = 1.23; 95% CI: 1.08–1.40). The PPV for AN was comparable when the cut-off was 20–40 µg/g higher in women than in men, for example at cut-off 40 µg/g, the PPV was 35.7% (95% CI: 34.0%–37.4%) in men, whereas it was 34.2% (95% CI: 31.8%–36.7%) at cut-off 80 µg/g in women (Table S2).

The consequences of increased FIT cut-off on relative sensitivity and specificity were similar overall for men and women for each type of colonoscopy finding (Fig. 3, Table S2).

Discussion

Summary of findings

We found an increasing risk of advanced adenoma and CRC detected at colonoscopy following two-stool FIT with increasing faecal Hb concentration. There was no clear association between the risk of having an advanced SSP and faecal Hb concentration. The consequences of increasing FIT cut-off for detecting AN and CRC among those with a maximal FIT ≥10 µg/g in terms of relative sensitivity and specificity were similar overall for men and women, whereas the PPV was higher in men than in women.

Interpretation of findings

One of the main purposes of colonoscopy in the screening context is to find CRC and to find and remove premalignant lesions. At the same time, the risk of interval CRC and death from interval CRC must be weighed against the available colonoscopy capacity [17]. We found that higher cut-offs substantially decreased the number of colonoscopies while still allowing for detection of many ANs and most CRCs in both men and women. For example, an increase in two-stool FIT cut-off from 10 to 20 or 40 µg/g would lead to meaningful decrease in number of colonoscopies with 40%–63% compared to cut-off 10 µg/g and a modest decrease in detected CRCs. The PPV for AN and CRC was higher in men than women for each cut-off, so if equal colonoscopy positivity in men and women is desired, a cut-off of about 20–40 µg/g higher in women than in men could be used.

We found no meaningful difference between men and women regarding changes in relative sensitivity and specificity. Our findings therefore suggest that (absolute) sensitivity and specificity in men and women participating in two-stool FIT may be different due of differences at cut-off 10 µg/g or below. Consequently, an increase in FIT cut-off proportionally modifies differences (if any) between men and women in sensitivity and specificity.

CRCs tend to bleed more than advanced adenomas, and FIT has previously been shown to have higher sensitivity but lower specificity for detecting CRC compared to advanced adenoma [18], which explains why an increase in the cut-off for FIT led to a slower increase in missed CRC than other findings. SSPs and nonadvanced adenoma rarely bleed [19], which could explain why we found no clear association between Hb concentration and the risk of advanced SSP.

Previous research

Many previous studies have assessed one-stool FIT performance in FIT participants, and the cut-off range considered for a positive FIT test varies between studies and clinical practice [1, 3, 5–7, 20] but often starts far above 10 µg/g. We expect that the maximum of a two-stool FIT would have higher sensitivity for AN and CRC compared to one-stool FIT at the same cut-off, and that a cut-off for two-stool FIT would have similar specificity as lower cut-off for one-stool FIT, as indicated in a previous SCREESCO substudy in which participants who had already agreed to PCOL were invited to perform a two-stool FIT test ahead of the investigation [21].

A Danish study by Njor et al. estimated the optimal cut-off by weighed sensitivity and specificity equally and found that a cut-off of 9 µg/g to be optimal and in this case the number of colonoscopies needed to detect one CRC was 24 which was much lower than ours (40.9) [1]. That study, however, only used a single FIT test instead of two tests, invited individuals in a wide age (range 50–74 years) and included CRCs diagnoses registered in the Danish National Pathology Data Bank and the Danish National Patient Register up to 2 years after the FIT.

Several studies show that the prevalence of AN and one-stool FIT performance for detection of CRC or advanced adenoma differs between men and women at different cut-offs [8, 9, 13, 20, 22–24]. An English study using a cut-off 10 µg/g reported no difference in risk of missed findings [25]. In contrast, using 2 µg/g as cut-off, the sensitivity was higher among men than women (47.6% vs. 30.7%), and the specificity was lower (85.0% vs. 89.5%) for detecting advanced adenoma or CRC in a German screening setting [9]. The findings in the German study indicate that some important findings would be missed even with FIT cut-offs below 10, especially among women, and that sex differences (if any) would be introduced at very low cut-offs, which is in line with our findings.

To our knowledge, there is no consensus on which screening outcomes should be equal between men and women to offer equal opportunities to reduced CRC mortality in the long run. The rationale for choosing a FIT cut-off has in some cases been to select cut-offs that produce equal proportions of FIT-positivity in men and women [13], leading to more colonoscopies performed in women than in men. Differential cut-offs have also been proposed to achieve either similar risks of false positive FIT-tests in men and women, using a lower cut-off for women, or alternatively similar risk of false negative FIT-tests using a lower cut-off for men [23]. The availability of resources will also influence the cut-off adopted by national screening programmes.

We found that a higher cut-off for two-stool FIT in women than in men of about 20–40 µg/g would result in comparable colonoscopy positivity, which is the opposite of what is currently used in the Swedish screening program of Stockholm–Gotland using one-stool FIT (80 µg/g for men and 40 µg/g for women) [13]. Whether equal cut-offs will result in equal opportunities for men and women to benefit in terms of colorectal mortality remains to be seen in the final analysis of SCREESCO.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. It covers most of Sweden in a screening-naïve population that has a unique FIT screening design based on two stool samples. These stool samples were taken with separate kits from two different bowel movements, preferably not on the same day, and these were analysed by one central laboratory using a single OC-Sensor Diana automated analyser. We were able to study colonoscopy positivity and false positive and false negatives of multiple outcomes within an unusually wide range of FIT cut-offs. The participation in the FIT arm was high for both men and women, and the adherence to colonoscopy following a positive FIT was high for both men and women (91%) [14], compared to between 64.1% and 92.2% in European FIT screening programs [10]. Lesion detectability in SCREESCO was mostly acceptable although with room for improvement [26], but comparable with the NordICC study [16].

The numbers of adenomas, CRCs and advanced SSPs in individuals whose greatest FIT result was below 10 µg/g are unknown, which is a limitation of our study. Although the PPV for cut-offs from 10 µg/g can be interpreted in absolute terms, the false positive and false negative risks computed in this study should be interpreted as relative to the cut-off 10 µg/g, and these are informative of the decrease in false positives and increase in false negatives due to an increasing cut-off. In the instructions for use for Eiken OC-Sensor Diana, the lowest concentration in the measurement range was stated to be 10 µg/g, which was the recommended cut-off by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Diagnostic Guidelines [27] for symptomatic patients and is unusually low compared to other RCTs and clinical practice [28]. It is questionable if detection limits below 10 µg/g would be clinically meaningful.

Furthermore, there is evidence from the SCREESCO study and elsewhere that faecal Hb concentrations below 10 µg/g effectively rule out CRC [21, 25]. For example, the previously mentioned SCREESCO substudy found 704 of 806 participants to have a two-stool FIT result below 10 µg and, of these, none were found to have CRC, and only 60 (8.5%) were found to have advanced adenoma at colonoscopy [21]. Second, from the findings of the SCREESCO PCOL arm, we would expect 153 CRCs in the FIT arm participants undergoing the test (CRC found in 0.46% of those undergoing PCOL × 33,383 undergoing the FIT test); this is almost exactly equal to the 155 CRCs detected in FIT arm colonoscopies following a two-stool FIT test result of 10 µg/g or more, suggesting no CRCs in those with a result below 10 µg/g [14].

We did not have data on undetected lesions, and a future analysis of interval cancers will indicate impact of lesions not detected. Despite these limitations, we argue that our study presents an important contribution to the discussion around choice of FIT cut-off in the relevant range of faecal Hb concentration.

Generalizability

The findings of this study do not necessarily extend to other age groups currently under consideration for FIT screening [20]. Different risk groups of men and women may have attended screening differently in ways that we were unable to adjust for, such as socioeconomical factors [15] and lifestyle that may affect both faecal Hb levels and risk of any adenoma and cancer [29]. There are lifestyle differences between men and women, where men typically consume more alcohol, whereas smoking is more common among women [30], although these differences are less profound in Sweden from an international perspective, and the smoking habits of men and women in this study were comparable. Our findings regarding sex differences may not generalize to populations with larger lifestyle differences between the sexes. For this reason, we argue that FIT performance should be assessed by sex separately in the population where an optimal FIT cut-off is sought.

Conclusions

The risk of advanced adenoma and CRC increased with increasing Hb concentration in both men and women, and a low cut-off around 20–40 µg/g for two-stool FIT allows detection and removal of many advanced adenomas and CRCs. The findings suggest that a higher cut-off in women than in men could lead to comparable colonoscopy positivity for advanced adenomas and cancer.

Author contributions

Conceptualization; formal analysis; data curation; methodology; software; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing: Marcus Westerberg. Conceptualization; formal analysis; software; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing: Julia Eriksson. Conceptualization; writing—review and editing: Chris Metcalfe, Christian Löwbeer, Anders Ekbom, Robert Steele and Lars Holmberg. Conceptualization; methodology; project administration; supervision; validation; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing: Anna Forsberg. Marcus Westerberg, Julia Eriksson, Lars Holmberg and Anna Forsberg had access to the included study data. All authors agreed with the final decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for grants from the 18 Swedish regions, Stockholm County Council, Regional Cancer Center Mellansverige, Swedish Cancer Society, Aleris Research and Development Fund and Eiken Chemical. We are also grateful to the 33 Swedish hospitals where the colonoscopies in this study were performed. Late Prof. Rolf Hultcrantz is acknowledged for initiating SCREESCO, securing the funding and leading the study through the entire recruitment period and first report.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest.

Funding information

Swedish regions, Regional Cancer Center Mellansverige, the Swedish Cancer Society, Grant Number: 2018/595; Aleris Research and Development Fund, and Eiken Chemical. Financial support was also provided through the Regional Agreement on Medical Training and Clinical Research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, and by the Swedish. Society of Medicine Ihre Foundation, Grant Number: SLS-961166. The funders of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Open Research

Data availability statement

For data sharing questions, please contact the study principal investigator at [email protected]. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are available on request. De-identified individual participant data that underlie the results reported in this article (including in the appendix) can be made available to researchers after request to the SCREESCO Steering Committee. Researchers must provide a methodologically sound proposal for a project that conforms to the Swedish Ethical Review Authority permit for the project and will need to sign a data access agreement. Data sharing must also follow local rules and legislation and is feasible within the EU. Data will be made available at a secure remote server to achieve the aims in the approved proposal. Data will be available from 3 months after publication and until 3 years after publication of the article. Proposals regarding the data underlying this article may be submitted up to 2 years after publication. The SCREESCO study will not carry the costs of external projects.