Sharenting in an evolving digital world: Increasing online connection and consumer vulnerability

L. Lin Ong, Alexa K. Fox and Laurel Aynne Cook are equally contributed and the remaining authors are listed alphabetically.

Abstract

Sharenting (using social media to share content about one's child) is a progressively common phenomenon enabled by society's increased connection to digital technology. Although it can encourage positive connections to others, it also creates concerns related to children's privacy and well-being. In this paper, we establish boundaries and terminology related to sharenting in an evolving digital world. We conceptualize a modern sharenting ecosystem involving key stakeholders (parents, children, community, commercial institutions, and policymakers), by applying consumer vulnerability theory to explore the increased online connection that occurs as work, school, and socialization become increasingly more virtual. Next, we expand the characterization of sharenting by introducing a spectrum of sharenting awareness that categorizes three types of sharenting (active, passive, and invisible). Finally, we provide a research agenda for policymakers and consumer welfare researchers.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the number of social media users surpasses four billion (Hootsuite, 2022), the shifting yet pervasive impact of online sharing continues to be revealed. It has been just 2 years since the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, colloquially referred to as COVID-19 (“pandemic”). As of April 2022, 499.1 million cases and 6.2 million deaths are confirmed worldwide (NY Times, 2022). The pandemic serves as a catalyst in an already evolving digital world, disrupting lives and forcing parents and children to go online for work, school, and social interactions. Ninety percent of Americans agree that the internet has been essential to their lives throughout the pandemic, with 40% of US adults using technology in new ways since 2020 (Pew Research Center, 2021b). As consumers' tactics for addressing the pandemic continue to adjust to the “new normal,” reliance on online platforms and acceptance of virtual interactions have increased substantially. Thus, the pandemic created a unique overlap of increased vulnerability, online access, and need for connection, further evolving our dynamic digital world. For example, instead of inviting a classroom of students to an entertainment center for a birthday party, parents might opt for a small, at-home gathering for their child but post real-time photos to Instagram Stories to include other family and friends. As individuals become increasingly familiar with virtual events, sharenting (sharing content about a child via social media) has become increasingly normalized, which may impact digital rights and sharing for generations.

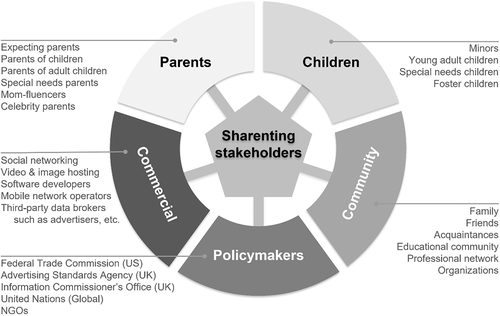

Despite the popularity of sharenting, academic literature lacks a broader and cross-disciplinary understanding of it within the marketplace. Thus, this paper makes three contributions to the literature. First, it grounds the concept of sharenting in the evolution of the digital world spurred by the pandemic. Specifically, we conceptualize sharenting in today's digital landscape as an interdependent network of multiple marketplace stakeholders: parents, children, audience/community, commercial institutions, and policymakers (Figure 1), To do this, we synthesize research from multiple fields (marketing, law, communications, privacy). While the sharenting literature generally focuses on the parent/child dyad (e.g., Holiday et al., 2022; Leaver, 2020), we argue that a richer conceptualization of the context, brought to light by an increasingly connected digital world, will aid understanding of how stakeholders make decisions and share information. These stakeholders are not isolated entities, but instead interact and share data in a complex and often hidden ecosystem that can make accountability difficult.

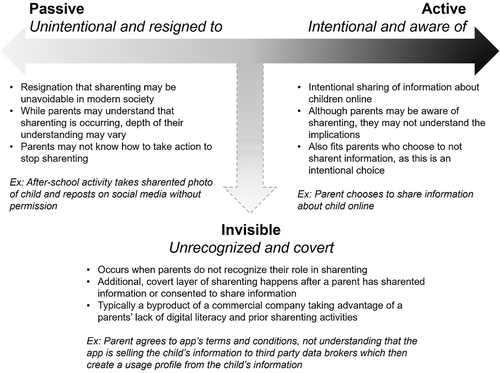

Second, we expand the characterization of sharenting by conceptualizing a spectrum of three different types: active, passive, and invisible (Figure 3). These categories underscore the temporal and behavioral nature of sharenting and are less understood than its motivations, which has been a focus of sharenting literature (e.g., Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017; Wagner & Gasche, 2018). Sharing personally identifiable information (PII) may be (un)intentional, but the consequences can be significant and long-lasting. We contribute the new term “invisible sharenting” (the covert sharenting that occurs when parents do not recognize their role in it). Invisible sharenting is especially an issue with the expansion of third-party data collectors, although to our knowledge, it has not been discussed in the context of sharenting. With this expanded definition of types of sharenting, we offer researchers and practitioners additional conceptual boundaries and vocabulary to contextualize their work. In particular, the definitions seek to avoid the jangle fallacy, where different terms used for the same construct (Kelley, 1927). With our unified explanation of sharenting's concepts, we promote progress in the literature and establish key boundaries in the ongoing study of sharenting.

Finally, we present impacts of sharenting for marketing and public policy, in the context of consumers' increased online connections. We identify common problems and offer recommendations for sharenting actors. With a paucity of suggestions for future research in the literature, we offer a research agenda for each stakeholder group (Table 1); our contribution is designed to maximize our understanding of sharenting and to broaden the impact of future sharenting research in the modern digital world.

| Stakeholder | Example research questions |

|---|---|

| Parents |

|

| Children |

|

| Audience/Community |

|

| Commercial interests |

|

| Policymakers |

|

2 THE SHARENTING DILEMMA

Digital technology's pervasiveness in everyday life is increasingly changing childhood, raising concerns about children's digital privacy from global organizations such as the United Nations and UNICEF. This already accelerating trend was put into sharp relief during the pandemic, which resulted in the World Health Organization recommending lockdowns and social distancing to slow the spread of the coronavirus (WHO, 2021). Many children saw their daily educational and social routines moved online to decrease risk of in-person transmission, however children's vulnerability increases as their digital footprint expands (UNICEF, 2021).

Consumer vulnerability is a temporary condition where consumers could be subject to harm in the marketplace in terms of their access to and control over resources (Hill & Sharma, 2020). It can be closely linked to one's identity, especially during times of transition. The pandemic was a key time of change, with parents often unsure of how to navigate an unknown and fluctuating environment, having no choice but to spend more time online to continue to maintain a sense of connection for themselves and their children. Simultaneously, as the owners of their children's information, parents authorize who becomes co-owners (Petronio, 2002) of the shared information. For example, a father may post a photo of his child to Facebook and make the post visible only to his Facebook friends. However, unintended audience(s) may also gain access: if one friend downloads the photo and reposts it, the information is now shared beyond its intended audience. As sharenting increases, such situations offer additional opportunities for parents to experience vulnerability. In the next section, we seek to better understand the sharenting ecosystem, characterized by the five key stakeholders, shown in a new and broadened integrated framework (Figure 1). We focus on US and UK legislation, although many of the ideas can apply globally.

3 STAKEHOLDERS

3.1 Parents and guardians

Sharenting is at minimum a two-person endeavor, requiring at least a parent or guardian (the sharer) and a child (the shared). Parents are legally responsible for the PII that is sharented, acknowledging that a child's data privacy may be interdependent with the parents' data privacy (Kamleitner & Mitchell, 2019), modeling to their children what is acceptable to share, and negotiating sharenting behaviors with their children (Steinberg, 2016). Sharenting parents are also the first generation to grow up with social media, which leads to certain vulnerabilities: while they are familiar with the technology, this closeness can create a false sense of trust, as they may be unaware of the full impact of sharenting. The pandemic exacerbated issues around sharenting by straining vulnerabilities experienced in the transition to and within parenthood.

Looking at specific groups for examples, parents of school-aged students have seen an increase in online systems for remote learning. Adopting technology to aid educational experiences may lead parents to analyze these technologies less critically. Next, parents of immunosuppressed children may feel more isolated without physical access to typical support, possibly altering their motives to sharent to connect with other like families (Boyd-Barrett, 2020). Moreover, adoptive families face unique situations related to sharenting motivations that have changed with the digital landscape such as online posting rights between biological and adoptive parents (Steinberg et al., 2022). Finally, given the pandemic's economic fluctuations, parents may be more likely to sharent to support trusted companies (see Figure 2a).

3.1.1 What is sharented and why?

Sharenting can occur at any stage, from expectant parenthood to parenting older children. It takes place on a spectrum of awareness (Figure 3), from active, intentional sharenting to instances where parents may not even recognize that they are sharing PII (“invisible sharenting”). Given the diversity of forms sharenting can take, the decision for parents and those studying the phenomenon is highly complex.

Even before the pandemic, sharenting included various types of content, such as photos of milestones (e.g., crawling), outings (e.g., birthday parties), daily life, and cute or funny moments (Brosch, 2016; Kumar & Schoenebeck, 2015). Other frequent topics include children's sleep, nutrition, discipline, and school (Davis et al., 2015). Parents may sharent to seek affirmation and advice, to share their pride in their children, to archive memories, to help other parents learn from their experiences, and to stay in touch (e.g., Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017; Wagner & Gasche, 2018). In turn, they receive feedback from other parents (McDaniel et al., 2012), which makes them feel supported. Sharenting is especially common among mothers, who may desire to portray being a “good mother” (Fox & Hoy, 2019; Lazard et al., 2019). Sharenting can empower mothers to make more informed decisions (Holtz et al., 2015), which is particularly important given the uncertainty of the evolving modern digital world. The literature points to sharenting as an opportunity to present children as a narration of parents' aspirations and abilities; however, parents' confidence may be undermined or overwhelmed by the variety of digital choices, leading to further opportunities for vulnerability.

3.1.2 Monetized sharenting

Approximately 4.5 million influencers represent an $11 billion industry (Krueger, 2019; Lenz, 2019). Parental influencers sharent their family life for profit (Campana et al., 2020). Parents use stories and images of their children as part of their monetized posts, choosing to do so despite potential privacy concerns (Archer, 2019a, 2019b). Their children attract attention and further lose their privacy because followers can “store, republish and recirculate information” (Abidin, 2015, p. 5).

Perhaps the dominant societal impact of these monetized sharenters is that sharenting “has become normalized as commercially motivated influencers prompt everyday (parents) to consider the benefits of sharing” (Campana et al., 2020, p. 54). “Mediatisation,” the gradual process where media molds social and cultural activities (Jansson, 2002), can also lead to increased sharenting beyond monetized situations. Next, we review key literature to demonstrate how sharenting has created new and untested opportunities for other members of the ecosystem.

3.2 Children

Social media platforms may use sharented content to create an information repository about users. Companies can use such information, some of which is provided in response to brands' social media engagement tactics (Fox & Hoy, 2019), to begin to track personally identifiable information in gestation and early infancy. Even third-party websites and applications can track intimate health and well-being details being offered by sharenting (Lupton & Williamson, 2017). However, because young children are not developmentally able to understand sharenting-related issues, they cannot be considered legally competent to provide (or refuse) informed consent (Nottingham, 2019). The digital footprint that their parents create can follow them into adulthood (Steinberg, 2020).

Findings from a study early in the pandemic suggested that children generally have negative feelings about sharenting, with kindergarten-aged children being the least receptive compared to older children (Sarkadi et al., 2020). For teens, sharenting may even seem hostile if it conflicts with their own identity formation or creates an opportunity for peer ridicule. Adolescents feel more negatively about sharenting when they perceive that their parents sought impression management rather than information archiving (Verswijvel et al., 2019).

Consumers in the transitional stage between childhood to young adulthood are also impacted by sharenting. The United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child provides the international standard definition of an adult as someone above 18 years of age. These consumers are legally adults, but they may still be dependent on their parents for financial and/or emotional support. During the pandemic, over half of Americans aged 18–29 moved in with their parents, surpassing the previous peak from the Great Depression (Pew Research Center, 2021a). Since such consumers are cognizant of their digital identities, they are more prone to engage in conflicts with their parents if the digital images their parents create for them contradict their identities. They may also be more aware of the rights granted by related privacy regulations and thus more likely to use laws to defend themselves in sharenting conflicts (Schoeman, 1987).

3.3 Audience/community

Beyond the parent/child dyad, a variety of stakeholders must be considered that engage in indirect sharenting (i.e., encouraging parents to share) or direct sharenting (i.e., posting children's PII themselves). While it is commonly parents who authorize and become co-owners of their child's information, the community may play a role in sharenting as well. Specifically, those with access to children's PII may make such information publicly available.

For example, parents can feel pressure from other family members to share PII, which can then be reshared online out of their control. Schools' social media pages and websites may present information about children and their families, with parental consent forms giving parents confidence in the sharing (Cino & Vandini, 2020; see Figure 2b). Throughout the pandemic, schools have reached out to parents, encouraging them to film their families and tag themselves on social media (Bessant et al., 2020). This approach arguably has multiple benefits: enabling children to keep up with their peers, helping foster a sense of community with fellow pupils, and providing visible support for the school as an institution. However, some parents also raise concerns about teachers sharing information not only on school websites but also on their own social media (Figure 2). Similarly, parents may consent for the school to use a learning management app that then stores the child's PII and photos on a server, resulting in unrecognized, or “invisible,” sharenting. Digital sharing allows for greater opportunities for unauthorized individuals to become co-owners of the information compared to a physically limited context, such as a bulletin board in a school's hallway.

Nonprofit organizations also become (un)authorized co-owners of children's PII, which they may sharent. Places of worship and child-focused organizations, such as the Girl Scouts, post pictures of the children in their care to emphasize their activities and mission. Law enforcement agencies also use social media for community policing; to “humanize the badge,” agencies post pictures of officers engaging with children (Carter et al., 2020).

3.4 Commercial institutions

Seventy-eight percent of parents with a child younger than 12 years of age agree that children should be 12+ before using social media sites and apps (Auxier et al., 2020). Nevertheless, only a small subset (18%) use social media without sharenting. Commercial institutions are largely responsible for promoting parental sharenting. For example, many children's brands prompt parents to tag them on social media (Fox & Hoy, 2019; see Figure 2b). Some posts include PII, as defined by the US Children's Online Privacy Protection Act Rule (COPPA; e.g., photos with geotagged locations). The business model of online service providers also reflects commercial interests in sharented information. Third-party data brokers can also collect data from online user activity to create profiles or segments, which can be sold and used for a variety of marketing functions (e.g., ad personalization). Described as the “datafication of childhood,” information can be collected as soon as early gestation from ultrasound images and pregnancy apps (Mascheroni, 2020, p. 798). Children's data from commercial institutions has never been more accessible or widespread.

Researchers with the Kids Online Anonymity and Lifelong Autonomy (KOALA) project found that both parents and children failed to understand apps' data collection practices, which often include transmitting such data to third-party companies (Zhao, 2018) or storing personal information (Yao et al., 2017). A study of thousands of apps for children showed that 73% had potential COPPA violations where sensitive data was shared without parental consent (Reyes et al., 2018), increasing children's vulnerability online.

While technology has been positively used to teach children and trace contacts during the pandemic, NGOs point to children's vulnerability when content is not stored appropriately, or governments expose the identity of individuals being tracked for public health purposes (UNICEF, 2020). Recognizing the impact that the pandemic had on children's use of digital media for learning and entertainment, the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood and Center for Digital Democracy have been advocating for the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to require big tech companies to reveal how they target children and what type of data they are collecting (Chester & Golin, 2020).

Finally, in response to growing concerns from parents and new regulations, tech companies are creating products and tools that divert some control back to parents. For example, Facebook announced plans to launch Instagram Kids, targeting children under 13 and granting substantial parental controls. The move was met with extensive criticism from legislators and parents concerned about children's vulnerability related to social media, and in September 2021, Facebook announced that it would pause the project amidst these concerns (Meta, 2021). But some welcomed the app as a first step to educate children about social media while under the wing of a parent; thus, it will be critical for Facebook (and other companies looking to release similar products) to demonstrate the value of a child-focused platform.

3.5 Policymakers

Next, we turn to laws and regulations that govern the use of children's information. Jurisprudence generally reflects an assumption that parents are the best people to make decisions for their children and that the state should be slow to intervene, even where some harm to the child may result from parental decision-making. As part of its mission to protect consumers against deceptive and unfair business practices, the FTC protects the online privacy of US children under 13 by enforcing the 1998 COPPA (FTC, 2013) and its 2013 revision (FTC, 2015).

In England, legal protection for children's information derives from either the common law (which affords protection to individuals' confidential and private information) or the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA, 2018) and UK General Data Protection Regulation (UKGDPR). In addition, numerous regulatory codes govern the use of children's information by advertisers, broadcasters, and the media. COPPA provides explicit recognition of the need to offer greater protection to children than to the wider population. English courts have also recognized the special position of children and the importance of protecting their privacy (e.g., Weller v Associated Newspapers Limited, 2015 EWCA Civ 1176). The UKGDPR similarly recognizes the vulnerability of children; Recital 38 explicitly states that “children merit specific protection with regard to their personal data.” From September 2021, the ICO's Age Appropriate Design Code requires online services to meet certain standards designed to provide additional protection to children's data when children engage online.

The Better Business Bureau's Children's Advertising Review Unit provides guidelines to help companies comply with COPPA. Similarly, the U.K. Advertising Standards Authority sets out in the codes for media (CAP/BCAP codes) that certain rules must be followed by advertisements directed at or featuring children. The UKGDPR recommends that specific protection should be provided to children's personal data “for the purposes of marketing or creating personality or user profiles and when data is collected by children ‘using services offered directly to a child.’” Some academics have suggested a child might use the right to erasure/right to be forgotten to remove information (Rustad & Kulevska, 2015; Steinberg, 2017) regarding commercial activity. However, the analysis applies specifically to European countries; US law has not even begun to analyze how the right could apply in any context at all.

3.5.1 The parent as privacy guardian and the discloser of family information

The parent is generally viewed as the most appropriate person to make decisions regarding a child's information and images. COPPA affords parents of children under 13 control over online collection of their children's PII by commercial websites and online services. Similarly, UKGDPR imposes an explicit obligation upon organizations offering information society services (UKGDPR—Article 8) to a child, and relying upon consent to process that child's personal data, to obtain parental consent for a child under 13.

In England, a child may bring an action against their parents or any other person if they believe that sharenting has resulted in misuse of their private information (Bessant, 2018). It remains unclear, however, how the courts would determine such a dispute. Cases such as Newman v Southampton CC (2021) EWCA Civ 437 and Re J (a child) (Contra mundum injunction) (2013) EWHC 2694 (Fam) confirm that parents do not have an absolute right to determine whether their children's information is made publicly available and that while respect must be accorded to a parent's views, their exercise of their Article 10 right to freedom of expression cannot justify conduct that interferes with a child's Article 8 right to privacy to a harmful extent. Nonetheless, if the child is effectively asking the court to condemn parents for sharenting information, it is questionable whether the courts would be willing to depart from the approach taken in a string of cases where they seemingly accept that parents are entitled to share information about their family, even at the child's expense (Weller v Associated Newspapers Limited [2015] EWCA Civ 1176, Murray v Express Newspapers plc [2008] EWCA Civ 440; AAA (by her litigation friend BBB) v Associated Newspapers Limited [2013] EWCA Civ 554).

The United States also offers deference to parental rights. The Constitution enumerates an individual's right to free speech; the right to privacy is not specifically stated but is established through judicial precedent and found in federal and state statutes. While children certainly have an interest in privacy, it is likely that it will be given less weight than parental rights in the context of both free speech and the right to control a child's upbringing. US courts recognize that individuals have privacy rights, but children rarely have privacy rights separate and apart from their parents (Shmueli & Blecher-Prigat, 2010).

While courts seem protective of family privacy and sometimes children's privacy, they place far more weight on parental autonomy. Even in statutes that give children a right to privacy, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), and COPPA, the parent is the rights-holder. A potential conflict of interest exists in sharenting, as parents are both disclosing the child's information and generally tasked with protecting the child's digital footprint (Steinberg, 2017).

4 IMPLICATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH OPPORTUNITIES

Given the double-edged sword of children's increased online connection and vulnerability in today's evolving digital world, ample opportunities exist to address the implications faced by the key stakeholders in the modern sharenting ecosystem (parents, children, community, commercial institutions, and policymakers). In the following section, we discuss the significance of our research for each stakeholder, describe the spectrum of sharenting awareness (Figure 3), including types of sharenting for each stakeholder, and summarize a research agenda by stakeholder.

4.1 Parents

Parents are legally responsible for deciding which PII should be sharented and how. Recognizing parents' differences in sharenting preferences is important for working toward proposed solutions. Thus, we consider parents' active, passive, and invisible sharenting along the spectrum of awareness (Figure 3).

First, active sharenting is intentional and can occur in a variety of scenarios. While these parents are aware of their posting, they may or may not understand its implications. For example, parents may feel that they are familiar with the graphical user interface of a social media platform and therefore understand how it works. Yet, the complexities of how information is collected, stored, and reused, and the permanency by which this occurs, may elude them, especially in a parenting world that increasingly relies on many different technologies. Thus, parents who believe they are sharing information may actually be surrendering it (Walker, 2016), increasing their consumer vulnerability. On the other end of the spectrum, parents may decide not to sharent any information; because of the intentionality, this is considered an active sharenting-related decision as well. Again, they may make this decision out of basic awareness or full understanding, meaning that some parents who choose full protection may believe they are choosing not to share information when, in reality, they are choosing not to surrender it.

Next, passive sharenting occurs as a feeling of resignation, in that sharenting may be perceived as unavoidable in modern society. Although parents may understand that sharenting is occurring, the depth of their understanding may vary. The isolation of the pandemic results in parents seeking unique ways to keep themselves and their children tied to family, friends, and school/extracurricular opportunities. If online connections offer a feasible way to do this, parents may increasingly acquiesce or even become indifferent to sharenting, increasing passive sharenting and their own vulnerability.

Finally, we identify invisible sharenting as occurring when parents do not recognize their role in sharenting. This additional, covert layer of sharenting happens after a parent shares information; it is primarily initiated by commercial interests (authorized co-owners use it in unauthorized ways). For example, a parent shares photos of a child with family members via a cloud storage platform, not recognizing that the company is downloading the photos and sharing them on other websites. Parents also may not recognize that cloud storage may mean storing the content on third-party servers. The parents are not deliberately sharing the information so widely. Invisible sharenting is typically a byproduct of a company taking advantage of a parents' lack of digital literacy and prior sharenting activities.

4.1.1 Parents: A research agenda

Academic research should first explore how information about sharenting can be translated into guidance that is relevant and useful to parents in a world of increased online connection. Scholars can build off work by Brosch (2016), who suggested creating a sharenting score, and assess sharenting with empirical measures, such as the Sharenting Evaluation Scale (Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2022), which may make it easier to understand the amount and impact of sharenting. It is important that parents not feel overwhelmed by sharenting-related education; the language and framing should be supportive rather than making them feel defensive. Second, establishing the spectrum of sharenting awareness identifies a key knowledge gap to understand invisible sharenting; it represents a clear overlap of commercial interests and children's vulnerability, and work is required to understand this area to better protect children's information security and privacy. Future research should provide useful approaches for parents to assess their choices, which must go beyond the standard privacy and terms and conditions policies, which are difficult for consumers to understand (Fox & Royne, 2018), and establish a clear understanding of the risks so that policymakers can develop marketplace boundaries. Third, research should examine how passive sharenters can take a more active role. Walker et al. (2016) describes that an important component of sharing (versus surrendering) information is understanding one's actions and the actions of relevant others, which underscores the importance of parental education. Scholars should not only advance knowledge through empirical testing but also distill it into practical “how-to” guides that can be promoted by the community, social media, and regulatory stakeholders alike.

4.2 Children

First, active sharenting implies parental intentionality and is likely to have the greatest awareness from the child. A child's desire to be sharented can change over their lifetime and as they gain more understanding about what it means and how it may impact their current and future interactions. Both passive and active sharenting may include unwanted attention from unintentional co-owners of PII, distribution of sensitive information, and potential peer pressure impacts. Although parents do not deliberately engage in passive sharenting, it may have similar impacts on the child, due to PII being distributed without the child's consent.

Finally, young children are least likely to identify invisible sharenting, because it is covert. Although parents may not seek to deliberately deceive, older children, such as young adults, may be aware of the risks of sharenting. Nevertheless, the impact is difficult to quantify, and children might accept it as an aspect of growing up in an increasingly digital community.

As sharenting becomes pervasive for online influencers, this additional socialization may shift the overall cultural understanding and acceptance from the child's perspective. For example, even if a child is not in a “mom-fluencer” family, if they grow up watching toy demonstration videos and vlogs from other families, they may begin to assume sharenting is an acceptable part of their own childhood experience.

4.2.1 Children: A research agenda

Several areas should be explored further when considering sharenting from a child's perspective. First, research should examine children's understanding of how the sharenting ecosystem works, given the potential vulnerability from increased online connection. This can help to identify ways to increase children's digital literacy regarding the benefits and risks in an age-appropriate manner and can increase understanding of how family identities are shaped through modern sharenting practices. Scholars can explore how sharenting exposure is heavily impacted by stakeholders outside of the parent/child dyad, such as marketers. Finally, probing training, regulation, or other protections with the lens of invisible and passive sharenting can increase the understanding of children's safety in this new normal.

4.3 Audience/community

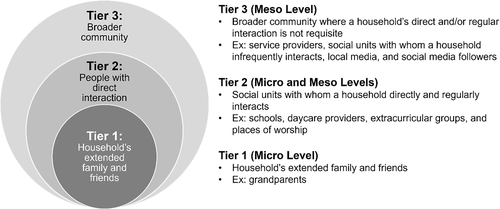

A three-level visualization of household interaction is helpful to consider the “ripple effects” of sharenting to increasingly expansive circles (see Figure 4). Tier 1 includes a household's extended family and friends. Grand-sharenting is a common and relatable example: grandparents who experience the joy of a grandchild's arrival may enthusiastically repost information about that child with the assumption that this is their prerogative (e.g., Cino & Vandini, 2020). This first tier of community-based sharenting presents social complications, as the personal relationships between sharers can be impacted by prior family history, expectations, and more. While a child's healthcare information, for example, can be managed by parents without significant community interference, the control of other PII—including photos and videos—is more fraught.

Tier 2 includes social units with whom a household directly, and regularly, interacts. Schools, daycare providers, extracurricular groups, and churches are typical examples. Schools have a unique advantage in access to a child's information. In the United States, FERPA outlines how public schools can share students' information with third parties upon request and without parents' consent. Such “directory information” includes PII, such date of birth, home address, photos, and some medical data (e.g., height, weight). Sharenting via the digital platforms that have become more popular during the pandemic may put these regulations to the test.

Tier 3 includes the broader community, where a household's direct and/or regular interaction is not requisite. For example, the U.S. Kimberly-Clark brand Huggies advertised game-day newborns during the 2021 Super Bowl. An omnichannel marketing campaign shared a birthdate, picture, first name, time, and location for eight babies, albeit with parents' permission (Cision, 2021). Any Twitter user who browses the associated #WeGotYouBaby hashtag becomes an information co-owner in this broader sharenting community. Other members of that community can include social units with whom a household infrequently interacts, local media, social media followers, and service providers. Even in a healthcare setting, which generally holds that patients' images require the same privacy safeguards as the rest of the medical record, images used for treatment, payment, or healthcare operations may not require patients' or parents' authorization (Romig, 2018) outside the jurisdiction of the GDPR. Although institutions may have strict guidelines for disseminating a child's information, enforcement at the employee level can be challenging and infrequent, especially as members become increasingly accustomed to sharing via online technology and if they receive positive reinforcement from their audiences.

4.3.1 Community: A research agenda

Community members who sharent may unknowingly increase children's vulnerability. While the privacy implications associated with sharenting depend on the level of identifiable information (Gross & Acquisti, 2005), the likelihood that community members are aware of such oversharing is much lower (i.e., in comparison to parents or children). Instead, passive or invisible sharenting among community members is more likely, and research designed to understand how consumers in a sharenting community use a child's personal data is warranted. Moreover, as each community tier recognizes and respects children's data, parents may see positive effects. For example, a hospital may include digital security education for new parents as a part of parent and family education. Another area of future research is the ripple effects of sharenting amplification (especially as community tiers transfer information back and forth), which could provide greater understanding of the impact of audience on sharenting. In addition, while it is parents who sharent, understanding the demand (“pull”) effect of information requests from their audiences/community can increase understanding of how parents' sharenting beliefs and actions are shaped. Future research can also explore the various types of consent that are most effective for understanding and preventing over-sharenting.

4.4 Commercial institutions

Businesses are another important stakeholder in the modern sharenting ecosystem, having access to and/or creating technologies that collect user PII. Information and behaviors represent a large portion of the data collected and often monetized. During the pandemic, remote learning environments increased access to children's data in new ways, including data breaches that compound privacy concerns; the average cost of a breach is estimated at $4.24 million USD in 2021 (IBM, 2021). Commercial stakeholders that collect and/or distribute children's data illustrate invisible sharenting. Such information is shared outside parents' control or without their knowledge. Data privacy advocates often recognize the potential for significant harm but are not commonly included in sharenting-related discussions. Questionable data collection/use may not be unlawful but can make data exploitable, increasing children's vulnerability. For example, educational apps that sell data to marketers may cause data to become misused, undermining educators' efforts to improve the quality of their teaching programs, reducing parents' trust and self-efficacy perceptions, and spurring policymakers to respond by creating regulatory interventions that may affect a business's bottom line.

Other commercial stakeholders who can encourage invisible sharenting include social media providers. For example, photo dumping (users take a selection of unrelated recent images from their device and “dump” them online simultaneously) is a recent trend (Cooper, 2021). However, as access to photos—including those of children—increases, so does their unintended use by other people (Besmer & Lipford, 2010) and the potential for invisible sharenting.

Social media providers suggest that users' information is protected—especially for children regarding exploitative content (Facebook, 2021). However, the design of many social media sites encourages third-party data collection to increase advertising revenue, which carries an inherent privacy risk that users are generally unaware of. For example, advertisers, app developers, and publishers can use The Meta Business Tools to develop user targeting and share user information collected on and off Facebook. Similarly, smartphones and other devices used by children often contain physical trackers that collect precise latitude, longitude, and timestamp data that third parties collect and sell to advertisers, retailers, and other commercial entities interested in consumer behavior (NY Times, 2019). This surveillance creates a location-based profile that can be used to identify a child without consent, leading to invisible sharenting.

4.4.1 Commercial: A research agenda

Since the area of commercial stakeholders is less understood, research should first assess the extent to which businesses collect sharented content. Second, regarding invisible sharenting, researchers can review the impact of third-party commercial interests to collect and use children's PII. Given the growing prevalence of the Internet of Things (IoT), data collection by businesses that sell IoT devices (e.g., app-connected toys, baby monitors) should also be considered. It would also be useful to understand the prevalence of brand-prompted sharenting, which occurs by mothers (Fox & Hoy, 2019) and fathers (Fox et al., 2022) alike.

Design tools and methodologies can provide commercial interests with clear guidelines when developing products with human-technology interaction. Design with Intent (DwI) (Lockton et al., 2008), considers ethically useful technological designs from commercial parties. Its orthogonal dimensions include commercial benefit, user helpfulness, and social benefit. Similarly, Privacy by Design (PbD) provides a systems-level perspective of technology design (Cavoukian, 2009) that will support a child's data privacy and reduce the likelihood of sharenting by commercial stakeholders. DwI and PbD could dovetail with research discussions about the explicit role of businesses, including social media and tech providers, in regulating how sharented data is collected and used.

4.5 Policymakers

Our conceptual framework is especially relevant for policymakers as they craft legislation designed to address problems created by sharenting in an evolving digital environment. While regulatory approaches vary significantly worldwide, policymakers are united by a common goal to create laws and regulations that benefit the public, although they may also be swayed by lobbyists from commercial interests. Acknowledging the many stakeholders in sharenting reveals a complex ecosystem that needs to be considered to develop and improve laws and regulations.

For example, COPPA focuses on data shared by children; it does not cover their parents. The FTC held a public workshop in 2019 examining “The Future of the COPPA Rule,” but dominant considerations remained protecting children who were personally online and thus either directly providing their data or having it indirectly collected (FTC, 2019). The EU GDPR does not currently address digital literacy, yet parents' likelihood to improve digital privacy practices is positively correlated with this important factor (e.g., Walker et al., 2016). Parents with low literacy may become more likely to opt out of GDPR-mandated disclosures—allowing for the commodification of their child's private information.

Several US initiatives have been suggested to improve the protections afforded to children's information: raising the COPPA age coverage to 16, enabling an individual over 13 or their parents to request that their PII be permanently deleted, and establishing a Youth Marketing and Privacy Division at the FTC (Markey, 2021a), the “Clean Slate for Kids Online Act of 2021” (Durbin, 2021), and the Children and Teens' Online Privacy Protection Act (Markey, 2021b). Legislation has been proposed to update COPPA (Castor, 2021) to give parents independent grounds to legally challenge unauthorized data collection (Steinberg, 2021). In England, while the draft Online Safety Bill (2021) evidences an increasing awareness of the potential for online harm to adults and children, it also focuses upon commercial entities. It only refers to children in the context of them accessing material that might cause them harm.

Different regulatory interpretations of the “significant harm” that may occur from all forms of sharenting (active, passive, and invisible) offer interesting policy implications. In most case law, a determination of significant harm usually warrants state or federal intervention. The likelihood of significant harm will need to be established, with risk management as a critical outcome. There are also implications from laws that empower parents, including those who want to stop others from sharenting. Citing the GDPR, a Dutch court required a grandmother to remove a child's images from Facebook and Pinterest (Roobeek & Picheta, 2020). However, similar rulings are unlikely in the United States because federal legislation regarding privacy is weaker than free speech regulations (Steinberg, 2020).

4.5.1 Policymakers: A research agenda

The implications of our work for policymakers will depend on current online privacy practices. For example, US websites can voluntarily disclose data collection practices, whereas this is not voluntary for EU and UK sites. Laws, such as the GDPR and UKGDPR, theoretically enable consumers to object to or opt out of companies' data collection, reducing perceptions of vulnerability. However, even mandatory regulation can lead to fragmented implementation practices or noncompliance (Bornschein et al., 2020) if enforcement is primarily indirect (e.g., competitors' legal disputes). Such regulation may imply a need for direct enforcement to improve effectiveness. Research can compare enforcement interventions. For example, third-party reporting could include (a) compliance with the law and/or (b) best practices in a consistent format that consumers trust—much like the UK Food Standards Agency rates restaurants' food hygiene practices and the US AAA rates hotels' cleanliness and conditions. Analyzing financial penalties and historical records of compliance would also be useful. Alternatively, government agencies could make compliance records publicly accessible. Policymakers and researchers should also consider self- and/or industry-level approaches.

Research may also consider how international organizations, including the UN, have promoted and supported policy development. Earlier this year, the UN offered a relevant comment: “the rights of every child must be respected, protected and fulfilled in the digital environment” (UN, 2021, p. 14). Of interest to the UN is policymakers' adoption of legislation compatible with international human rights standards. Research that sheds light on effective safeguarding practices, design standards, or action plans would be especially useful. Countries might also consider changing their current orientation, in which parents are protectors of children's rights, including privacy, to give children more autonomy.

5 CONCLUSION

Major changes in online communication have occurred since the pandemic began, broadening a digital landscape ripe for vulnerability and sharenting. Sharenting continues to evolve in the dynamic interaction of technology and culture. While parents and children have thus far been the most frequently researched stakeholders due to their common vulnerabilities, a systems view delivers the necessary structure to incorporate other marketplace actors into our understanding. Our road map for evaluating the five key stakeholders (parents, children, community, policymakers, and commercial institutions) and three different types of sharenting (active, passive, and invisible) in the sharenting ecosystem highlight the importance of understanding the scope of sharenting in an ever-increasing digital world. This framework facilitates a systematic and integrated approach for expanding sharenting research and related public policy.