First record of the bull shark Carcharhinus leucas (Valenciennes, 1839) from the Maldivian archipelago, central Indian Ocean

Andrea Parmegiani and Jacopo Gobbato should be considered joint first authors.

Abstract

Verified records of the bull shark Carcharhinus leucas are lacking in the Maldives. This study provides the first confirmed evidence of 23 sightings observed from 2013 to 2023 in the central and southern atolls of this archipelago. Most of the sightings occurred in close proximity to inhabited areas, where food waste is often discarded into the water, or in several dive sites, suggesting the presence of this species in different locations around central and southern atolls. Although further research is required to fully investigate the C. leucas population in the Maldives, this report documents and confirms its presence in this region.

The Republic of Maldives is renowned for the abundance of pelagic species and megafauna found in its waters. The significant diversity and abundance of shark species have increasingly attracted divers and shark enthusiasts and, since the 2010 shark fishing ban, shark tourism in the Maldives has become a significant source of income for the tourism sector, one of the primary resources of the country (Ali & Sinan, 2015; Zimmerhackel et al., 2018, 2019). It has been estimated that a single shark is worth more than $800,000 during its lifetime, which is significantly more than its meat or fins (De Maddalena & Galli, 2017).

A total of 37 species of sharks have been recorded in the Maldives, 14 of which belong to the requiem shark family (De Maddalena & Galli, 2017), including the recently added Carcharhinus brevipinna (spinner shark; Müller and Henle, 1839) after its sighting in the dive site outside of Koddoo harbor (Russo & De Maddalena, 2021). In the past 2 years, another dive spot emerged in front of Hulhumale harbor, gaining attention, thanks to the high probability of sighting dozens of C. brevipinna during a single dive. Interestingly, Carcharhinus leucas (bull shark; Valenciennes, 1839), another important apex predator, has been repeatedly sighted in both locations along with C. brevipinna. However, it is interesting to note that previous works, such as those by Randall and Anderson (1993) and De Maddalena and Galli (2017), did not mention C. leucas in the shark species of the Maldives, contrary to other cosmopolitan or Indo-Pacific-distributed Carcharhinus, such as Carcharhinus albimarginatus (silvertip shark; Rüppell, 1837), Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (gray reef shark; Bleeker, 1856), Carcharhinus altimus (bignose shark; Springer, 1950), C. brevipinna, Carcharhinus falciformis (silky shark; Bibron, 1839), Carcharhinus limbatus (blacktip shark; Valenciennes, 1839), Carcharhinus longimanus (oceanic whitetip shark; Poey, 1861), Carcharhinus melanopterus (blacktip reef shark; Quoy and Gaymard, 1824), and Carcharhinus sorrah (spottail shark; Müller and Henle, 1839).

The bull shark, being a euryhaline species, has a circumglobal distribution inhabiting the tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions of all ocean basins (Ebert et al., 2013). This species usually spends most of its life in shallow environments, typically in the first 30 m of the water column (Ebert et al., 2013), where they forage on a variety of animals, including teleost fish, invertebrates, elasmobranchs, turtles, dolphins, and birds (Compagno, 1984; Snelson et al., 1984). Nevertheless, different studies have demonstrated that this species exhibits a remarkable migratory behavior, particularly when faced with specific requirements (Smoothey et al., 2019; Soria et al., 2021). Additionally, their ability to traverse vast stretches of open ocean provides further evidence for their potential presence in geographically isolated regions such as the Maldivian archipelago (Lea et al., 2015). The bull shark is a large, slow-growing species with a total length that usually ranges between 257 and 314 cm, with a maximum length reported of 400 cm (McCord & Lamberth, 2009) and a sexual dimorphism where females grow slightly larger than males (Cruz-Martinez et al., 2005; Wintner et al., 2002).

Diving centers and safari boats in the Maldives have claimed the presence of bull sharks for many years, especially in coastal areas where fish waste discharge happens and shark feeding is carried out. Despite the significant presence and ecological importance of C. leucas, only a few unsustainable reports and no verified records of this species in the Maldives are available in literature (Ali & Sinan, 2015; Voigt & Weber, 2011).

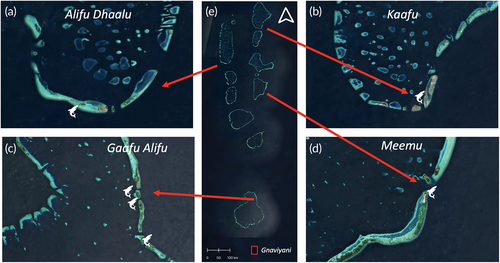

During a 10-year period between 2013 and 2023, 23 sightings of C. leucas were reported in various dive sites throughout the central and southern atolls of the Maldives. The study area included the central atolls of Kaafu Atoll, Alifu Dhaalu Atoll, and Meemu Atoll and the southern atolls of Gaafu Alifu and Gnaviyani Atoll (Figure 1).

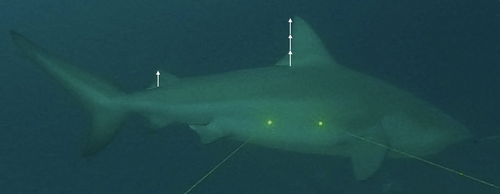

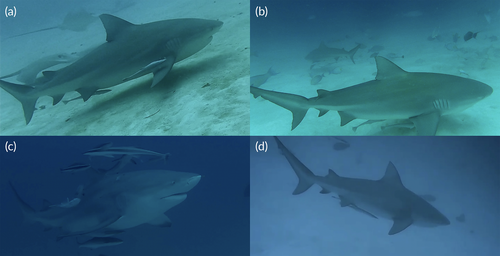

The sightings were obtained using different techniques and provided by different groups of people: the older records were collected by opportunistic sightings made by the safari boat crew of “Island Safari 1” between 2013 and 2020, confirmed by video evidence; the other records were obtained from visual census and video recording during diving activities of the White Wave Maldives diving team in 2022 and 2023. In addition, one of the sightings was captured using drifting Baited Remote Underwater Video Station (BRUVS; Supporting Information S1 and S2) systematically deployed by the authors over the past 2 years to survey the shark population in the Maldivian central and southern atolls. In the latter, BRUVS were placed at 25 m in front of Koddoo fish factory harbor in Gaafu Alifu Atoll for 73 min. Each image and video collected was analysed to confirm the accuracy of species identification based on the morphological description provided by Smith (1997), stating that C. leucas is a stout shark with a short, broad blunt snout; small eyes; and no interdorsal ridge. However, these characteristics may not be sufficient to distinguish this species, as sharks belonging to the genus Carcharhinus pose a challenge in identification due to the presence of numerous similar-looking species within the genus. In particular, in the case of C. leucas, the species is often prone to misidentification and confusion with its close relative, the sibling species Carcharhinus amboinensis (pigeye shark, Müller & Henle, 1839). Because the available data consist of only images and videos obtained from our observations or citizen science, genetic or further analyses cannot be conducted. Instead, to provide support in distinguishing and differentiating these closely related species, a thorough examination of the morphometric features has been employed. In fact, the ratio of the first to the second dorsal fin has been used as the sole investigative method based on the multimedia materials. In particular, if the aforementioned ratio exceeds 3.1:1, the species would be classified as C. amboinensis (Brunnschweiler & Compagno, 2008). However, in the present study, all the specimens exhibited a ratio equal to or below 3.1:1, confirming their positive identification as C. leucas (Figure 2). Furthermore, the sex of the individuals has been defined by the presence or absence of claspers based on Hendon et al. (2013).

After the data were collected and analysed, the sightings of C. leucas were associated with all the relevant metadata: dive site, conformation of the site, depth, number of individuals, sex of the specimens, and the presence of chum in the water during the observation (Table 1).

| Date | Dive site | Atoll | Site characteristics | Depth (m) | No. individuals | Sex | Food provisioning | Methods | Estimated size (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 13, 2013 | Furana Kandu | Kaafu | Kandu | 28 | 1 | n.d. | No | Video record | 2–2.5 |

| March 16, 2016 | Bodufinholu Thila | Alifu Dhaalu | Thila | 26 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| April 9, 2017 | Muli Kandu | Meemu Atoll | Kandu | 25 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| February 5, 2018 | Nilandhoo Kandu | Gaafu Alifu | Kandu | 35 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| February 20, 2021 | Maamendhoo Kandu | Gaafu Alifu | Kandu | 30 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| February 19, 2022 | Koddoo HR | Gaafu Alifu | House Reef | 38 | 1 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| February 23, 2022 | Koddoo HR | Gaafu Alifu | House Reef | 35 | 1 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| April 10, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 2 | Female | Yes | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| Female | Video record | 2.5–3 | |||||||

| April 30, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 40 | 3 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| Female | 2.5–3 | ||||||||

| Female | 2.5–3 | ||||||||

| May 1, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 25 | 1 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2.5–3 |

| May 8, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 40 | 1 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| May 13, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 20 | 1 | Female | Yes | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| June 22, 2022 | Fuvahmulah | Gnaviyani | House Reef | 10 | 1 | Male | Yes | Video record | 1.5–2 |

| November 24, 2022 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 40 | 1 | n.d. | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| March 2, 2023 | Koddoo HR | Gaafu Alifu | House Reef | 25 | 1 | n.d. | Yes | BRUVS | 2 |

| March 9, 2023 | Koddoo HR | Gaafu Alifu | House Reef | 35 | 1 | Male | No | Video record | 2.5 |

| April 2, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| April 9, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 1 | Female | Yes | Video record | 3 |

| May 6, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 2 | Female | Yes | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| Female | Video record | 2.5–3 | |||||||

| May 6, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 2 | Female | Yes | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| Female | Video record | 2.5–3 | |||||||

| May 7, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 1 | Female | No | Video record | 2–2.5 |

| May 8, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 1 | Female | Yes | Visual census | 2–2.5 |

| May 13, 2023 | Hulhumale HR | Kaafu | House Reef | 30 | 3 | Female | Yes | Video record | 2.5–3 |

| Female | Video record | 2.5–3 | |||||||

| Female | Visual census | 2.5–3 |

- Abbreviations: BRUVS, Baited Remote Underwater Video Station; HR, House Reef; n.d., not detected.

Regarding the sites considered in the study area, three different categories of site conformation were considered: House Reef, Kandu, and Thila. The term “House Reefs” refers to coral reefs in front of local islands and resorts, easily accessible from land. The Dhivehi (Maldivian local language) term “Kandu” refers to the channel entrance found on the outer island that limits the atolls. These sites are usually recognized as important aggregation spots for pelagic fauna, including predatory fishes like sharks, thus attracting a significant number of recreational divers. The term “Thila” instead, refers to the submerged pinnacles found inside atolls or channels, usually characterized by a top reef at c. 10–15 m. Moreover, the presence of feeding activities was evaluated in each site to differentiate the sightings that occurred in baited/feeding situation from those that occurred in natural situations.

The 23 sightings of C. leucas were spread in seven different locations in the central and southern atolls, 18 of which were observed in House Reefs where feed was often present. The most recurrent site, with 13 sightings, was the dive site located in front of the Hulhumale House Reef (Figures 1b and 3). This higher occurrence can be explained by the presence of a significant amount of fish waste repeatedly discharged by fish factories, diving centers, and safari boats especially in the morning and afternoon. Further evidence of the attraction related to feeding is given by the other five sightings recorded in front of the Koddoo House Reef (Supporting Information S3), where similar feeding conditions are present, as well as one individual sighted close to the Fuvahmulah harbor entrance in Gnaviyani Atoll (Supporting Information S4), where diving centers exploit feeding to attract tiger sharks, Galeocerdo cuvier (Péron and Lesueur, 1822).

Of the remaining sightings, four occurred in Kandu, in particular Nilandhoo Kandu (Supporting Information S5 and S6) and Maamendhoo Kandu (Supporting Information S7), where C. leucas were sighted on the drop-off of the channels. In Muli Kandu (Supporting Information S8), a female C. leucas was sighted in the corner, and another large female was spotted cruising at 26 m in Bodufinholu Thila (Supporting Information S9).

The videos recorded in Nilandhoo and Maamendhoo Kandu (Supporting Information S5–S7) showed how the presence of C. leucas creates a high level of disturbance among C. amblyrhynchos aggregations, causing them to flee from its predatory behavior. Whereas the behavior exhibited in channels may suggest a prevalence or even a predatory behavior of C. leucas over C. amblyrhynchos, in other locations, such as Hulhumale and Koddoo House Reefs, bull sharks were sighted alongside C. brevipinna and C. amblyrhynchos (Bleeker, 1856), appearing to coexist even with the presence of feed in the water. This may be attributed to the different personalities that different specimens of one shark species can exhibit, as reported by Dhellemmes et al. (2021). On examination of the images captured on both identical and distinct days, we successfully distinguished two distinct individuals: a female with no lower caudal lobe (Figure 3c; Supporting Information S10 and S11) and another female characterized by the absence of the first dorsal-fin tip (Figure 3a,b).

Although there are not enough observations to hypothesize a possible social interaction or aggregation among different individuals, it is known that the presence of feed in the water can attract different shark species at once (Brunnschweiler et al., 2014). In this context, a recent study has demonstrated that shark feeding facilitates the development of social association between C. leucas (Bouveroux et al., 2021).

The individual recorded by one of the two drifting BRUVS systems deployed at Koddoo House Reef, instead, was sighted after 49 min swimming under the video station and returned at 57 min without showing any interest in the bait on both the occasions. This suggests that this species is present in the area beside the presence of bait, possibly confirming its typical distribution in shallow coastal waters (Ebert et al., 2013), with most of the observations in House Reefs.

In the 23 bull shark sightings, 30 individuals were counted, with 25 identified as females, 2 as males, and 3 of undetermined sexes due to poor visibility conditions and video quality. Therefore, the majority of the C. leucas observed were adult females, especially at Hulhumale House Reef, where no males were recorded among the individuals observed. Although this database certainly requires further development, these observations suggest a trend toward female dominance, consistent with the sex-based aggregation patterns observed in both this species (Werry & Clua, 2013) and other species, such as C. amblyrhynchos (Economakis & Lobel, 1998), C. melanopterus (Speed et al., 2011), and Sphyrna lewini (scalloped hammerhead shark; Cuvier et al., 1834; Klimley, 1987). Moreover, the observations of bull sharks in the channel drop-off and their active predatory behavior (Supporting Information S4–S6) may indicate that this area functions as a potential hunting ground for these sharks, with C. amblyrhynchos being a potential prey, as observed with Sphyrna mokarran (great hammerhead shark; Rüppell, 1837; Mourier et al., 2013).

We recognize the importance of gathering additional data to enhance our understanding of the biology and ecology of C. leucas. However, it is crucial to highlight that our 10-year study strongly verifies the presence of this species in the region. The extent of spatial connectivity between the Maldivian population of bull sharks and other populations in the Indian Ocean remains largely unknown, necessitating further investigation that only tagging studies, along with the use of acoustic or satellite telemetry, could reveal. Currently, there is a lack of knowledge regarding the migration behavior of bull sharks in the north and central Indian Ocean, despite its potential for interesting population connections. Sightings of bull sharks have been recorded in various locations, including the Seychelles, the continental coast of the Indian subcontinent, Sri Lanka, and Reunion Island (Blaison et al., 2015; Fernando, 2014; Hoarau et al., 2021; Nevill et al., 2013). This remarkable distribution raises intriguing questions about their reproductive behavior, as they rely on low-salinity environments like estuaries, river mouths, and freshwater rivers (Gausmann & Hasan, 2022; Heupel et al., 2007; Snelson et al., 1984; Tillett et al., 2012). Therefore, it is more plausible that the Maldives serves as a foraging ground for adult bull sharks rather than a primary region for reproduction or nursery areas, as supported by our observations predominantly consisting of large female individuals. Understanding the location of nursery areas for the Maldivian population becomes therefore crucial to provide insights into the complex ecological dynamics and spatial distribution of bull sharks in the vast expanse of the Indian Ocean.

Furthermore, advancing our understanding of the ecological dynamics related to bull sharks can assist authorities in formulating effective conservation strategies to protect this species and enhance our overall comprehension of its role within the Maldivian ecosystem, as well as contribute to shark diving tourism in the Maldives thanks to this iconic species.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Jacopo Gobbato and Andrea Parmegiani; validation: Simone Montano and Davide Seveso; formal analysis: Jacopo Gobbato and Andrea Parmegiani; investigation: Jacopo Gobbato and Andrea Parmegiani; writing—original draft preparation: Jacopo Gobbato and Andrea Parmegiani; writing—review and editing: Simone Montano and Davide Seveso; supervision: Simone Montano and Paolo Galli. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank White Wave Maldives PVT. LTD. team and dive guides for the logistic support during the dives.