Insight Into the Diversity of Flower-Visiting Hoverflies (Diptera: Syrphidae) in Shrubland Maquis Around Ajaccio (South-West Corsica, France)

Funding: This study was supported by Collectivité de Corse—Ministère de la Cohésion du territoire et des Relations avec les Collectivités territoriales (2021): CPER No. 40137 and Association nationale de la recherche et de la technologie (ANRT) (2022): 2022/0393.

ABSTRACT

With around 6000 species and 200 genera worldwide, hoverflies (Syrphidae, Diptera) are important and a diverse group of pollinators, second to wild bees (Hymenoptera). Here, we studied the diversity of Syrphidae visiting flowers in low shrubland maquis environments of three compensation areas in the Ajaccio region (Corsica, France). A total of 138 hoverflies visiting flowers were sampled representing 27 species from 16 genera. The subfamily Syrphinae was the most diverse in comparison to Milesinae or Eristalinae. The syrphid communities were dominated at 67% by seven species (Eumerus barbarus, Sphaerophoria scripta, Chrysotoxum intermedium, Episyrphus balteatus, Syritta pipiens, Melanostoma mellinum and Melanostoma scalare). Most of data reported here are new for the Ajaccio region. Loretto stands out from the other two sites with both a greater species diversity and specimen abundance of hoverflies recorded visiting flowers. With regard to the daily activity, flower visits by syprhids occurred mainly during the morning at the three studied sites, and flowers of Asteraceae were the most visited. Finally, hoverflies showed a marked seasonality since most records of flower visits occurred in autumn (from September to November) when other floral visitors are rarer or absent.

1 Introduction

The Syrphidae (Diptera, Brachycera), also called hoverflies, are present in all biogeographical and continental areas of the globe, with the exception of the Antarctica. There are nearly 6000 species over 200 genera of hoverflies worldwide subdivided into three distinct subfamilies: the Syrphinae, the Eristalinae and the Milesinae (Doyle et al. 2020; Van Veen 2004). The larvae diet is highly diverse (saproxylic, phytophagous, saprophagous, sapro-phytophagous, aphidiphagous or non-specialist zoophagous), the adults are however more restricted as pollinivores and nectarivores (Holloway 1976; Keil, Dziock, and Storch 2008; Sarthou and Speight 2005; Schweiger et al. 2007; Seguy 1961). As a result, hoverflies are important floral visitors commonly observed both in crops and on wildflowers, particularly in the temperate zones (Larson, Kevan, and Inouye 2001; Woodcock et al. 2014). Syrphidae are considered as the third-most important and efficient pollinator family after the Apidae and the Halictidae (both Hymenoptera) visiting 52% of crops (Doyle et al. 2020). They also appear to be important floral visitors and pollinators in many natural ecosystems, and it is estimated that hoverflies may visit more than 70% of animal-pollinated wildflowers in Europe (Doyle et al. 2020).

In the Mediterranean, hoverflies diversity and ecological role are no exception, and they are abundant in arboreal and bushy environments such as shrubland or maquis (Castella, Speight, and Sarthou 2008; Petanidou, Vujić, and Ellis 2011). In this respect, hoverflies are good bioindicators, as some species are strictly found in very specific environments (Castella, Speight, and Sarthou 2008; Sarthou and Speight 2005). However, anthropogenic activities and their impacts on the environment are gradually becoming a threat to the diversity of Syrphidae (Schweiger et al. 2007). In Corsica, 168 species have been reported out of the 578 known in mainland France (Cornuel-Willermoz and Lebard 2024; Speight et al. 2018). The diversity of Corsican hoverflies has been studied since the 19th century (Bigot 1861, 1862; Becker et al. 1910; Cornuel-Willermoz 2021; Cornuel-Willermoz et al. 2023; Dirickx 1994; Doczkal 1996; Goeldlin de Tiefenau and Lucas 1981; Kuntze 1913; Lebard, Canut, and Speight 2019; Mengual, Lebard, and Cornuel-Willermoz 2023; Seguy 1961). Several recent intensive entomological surveys (La Planète revisitée leadered by the National Museum of Natural History in Paris) have been realised focusing mainly on hilly and mountainous habitats of Corsica, with 24 novel taxonomic reports for the island (Touroult et al. 2020; Ichter et al. 2022). They also captured several Corsican endemic species such as Eumerus niehuisi, Dockzal, 1996, Eumerus excisus van der Goot, 1968, Platycheirus cintoensis van der Goot, 1961, Eupeodes lambecki (Dušek & Láska, 1973), and the corso-sardinian endemic Eumerus vandenberghei Doczkal, 1996, Paragus ascoensis Goeldlin & Lucas, 1982, Paragus sexarcuatus Bigot, 1862, and Riponnensia daccordii (Claussen, 1991) (Ichter et al. 2022).

However, to the best of our knowledge, hoverflies from the region of Ajaccio have not been properly studied except from a field collection in September 2021 by the OCIC (Observatory & Conservatory of Insect of Corsica) reporting eight species: Chrysotoxum intermedium Meigen, 1822, Chrysotoxum cisalpinum Rondani, 1845, Milesia semilectifera (Villers, 1789), Myathropa florea (Linnaeus, 1758), Paragus bicolor (Fabricius, 1794), Syritta pipiens (Linnaeus, 1758), Syrphus ribesii (Linnaeus, 1758) and Xylota segnis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Cornuel-Willermoz and Lebard 2024). The present work is associated to the mitigation hierarchy (called ERCA sequence in French) of an industrial project, called Loregaz of the Engie company, located in Ajaccio, Corsica, France. The main objective of this regulatory sequence is to manage three natural zones of maquis in order to favour the conservation of three priority taxa: a reptile, the Hermann's tortoise (Testudo hermanni Gmelin, 1789) and two orchid species (Serapias neglecta De Not., 1844 and Serapias parviflora Parl., 1837). The maquis is a type of Mediterranean vegetation not very openly dominated by shrubs and small trees that are characteristically evergreen, small-leaved, xeric and 2–5 m tall. This biome develops generally on siliceous soils with crystalline and metamorphic rocks. The genesis of this type of environment is linked to human activities including agro-pastoralism and slash-and-burn, which favours pyrophytic plants while excluding tree formations in favour of dense shrub formations (Tassin 2012).

In the framework of these conservatory measures, we conducted a 9-month survey of the communities of flower-visiting adult hoverflies at the three sites managed in the Ajaccio region, South-West of Corsica. We did not aim to compile an exhaustive inventory but rather to have a functional approach in documenting observed hoverfly–flower interactions (see Section 2 for full details). Consequently, the taxonomic list provided here is only partial and must be considered as an insight into the total diversity of Syrphidae in the region of Ajaccio.

Our objectives were (i) to compare the diversity and abundance of flower-visiting hoverflies amongst the three study sites, (ii) to investigate their seasonal variations and diurnal activity patterns and (iii) to list the diversity of visited plant taxa.

2 Material and Methods

2.1 Study Sites

The study was conducted on three sites near Ajaccio namely, Loretto, Suartello and Vignola (Figure 1, Table 1). They constitute the ecological compensation zones for the Loregaz project of Engie and managed on its behalf by an association, the Conservatoire d'Espaces Naturels de Corse. The main vegetation on each site is the Mediterranean maquis and the sampling considered the environment differences in order to have a good representativeness of the ecosystems (Table 1).

| Locality | Geographical coordinates | Orientation | Main vegetation | Area (ha) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude, longitude | Altitude (m) | ||||

| Loretto |

41°93′35″ N 8°71′82″ E |

85 | South |

Wasteland [CORINE-Biotope: 87.1] Matorral with olive trees and mastic trees [CORINE-Biotope: 32.12] |

1.9 |

| Suartello |

41°95′31″ N 8°75′58″ E |

90 | South–South-East |

Grassland [CORINE-Biotope: 34.4] High maquis of the western Mediterranean [CORINE-Biotope: 32.311] |

2.5 |

| Vignola |

41°91′19″ N 8°65′00″ E |

30 | Southwest |

Medium maquis with Cytisus laniger and Pistacia lentiscus in mosaic with Olea europea [CORINE-Biotope: 32.215] Maquis with Cistus monspeliensis [CORINE-Biotope: 32.341] |

18 |

The Loretto site, located a few hundred meters from the city centre of Ajaccio adjoining the industrial Loregaz site, is made up of a plant mosaic, alternating open areas and old olive groves (Figure 1). The Suartello site, located on the edge of a wooded area, is a plant mosaic environment made up of an open (e.g., grassland) and shrubland environments. The Vignola site facing the sea (ca. 200 m inland) was partly degraded by heavy rotary grinding in 2018, 4 years before the study. The sampling included the ‘recovering’ environment as well as the closed environment making up most of the site. The proximity of the sites to each other makes it possible to consider their average temperatures and precipitation as being similar (Figure 1). Thus, they have a warm temperate climate with an average annual temperature of 1°C and an average annual precipitation of 526 mm. However, some differences exist: Vignola is exposed to sea spray and Suartello is a bit shadier.

2.2 Sampling Method

On each of the three sites, every 2 weeks from mid-February to mid-November 2022, hoverflies were only collected when visiting flowers during the different time slots of the day (9 am–5 pm). Hoverflies were hence sampled dynamically using a butterfly net, rather than passive traps such as malaise tents, emergence traps or colour plates (O'Connor et al. 2019). This sampling method was motivated by our functional aim to document the plant species diversity visited by anthophilous hoverflies rather than producing a complete syrphid diversity list. In addition, the studied sites been preserved ecological areas we wanted to have a limited impact on their respective (pollinating) entomofauna.

Two complementary sampling methods were used to record insect floral visits during each field sampling on each site at different times. First, a dynamic census along 2 linear transects of 30 × 2 m at slow speed (30 min per transect), located in two characteristic areas of the different sites. All hoverflies spotted to visit floral structures were captured with a net and stored in a freezer until their identification. Afterwards, they were mounted and pinned in our collection or preserved in 70% ethanol. The flower/inflorescence visited by the insect was identified to species level. Second, static observations of visiting hoverflies were performed for 5 min on two successive plants of 6 different plant species, i.e., 12 observations for 1 h per site. These plants were chosen for each sampling period according to their abundance in the flowering community. Monitored plant species hence varied throughout the year according to their flowering pattern. Overall, the 9-month sampling at Vignola resulted in 60 sampled transects corresponding to ~30 h of dynamic observations and 25 h of static observations of flower visitors. The sites of Loretto and Suartello were sampled similarly, with a total of 56 transects sampled, corresponding to around 28 h of dynamic observations and 26 h of static observations.

2.3 Hoverfly Identification

The morphological identifications of the syrphid specimens were done under a stereomicroscope with the help of several articles and reference books on French hoverflies (Seguy 1961; Speight 2020; Speight and Langlois 2020; Speight and Lebard 2020; Speight and de Courcy Williams 2021), on Western Europe hoverflies (Van Veen 2004) and Mediterranean species (Grković et al. 2015; Van Steenis, Hauser, and van Zuijen 2017; Malidžan et al. 2022). Also, the list published by the French National Museum of Natural History (MNHM) from la ‘Planète revisitée’ Corsican missions was consulted (Touroult et al. 2020; Ichter et al. 2022). In addition, some identifications were confirmed by Syrphid specialists in the genus Eumerus (Cavailles. S., and Lebard. T., pers. comm.) and for Merodon chalybeus Wiedemann in Meigen, 1822 (Sarthou. V., pers. comm.). Seven specimens were not yet identified at the species level but are recognised, for the moment, as distinct morpho-species for the diversity analyses. Their identification is in progress.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses and graphs were performed with Past statistical software version 4.16c (Hammer, Harper, and Ryan 2001). Beta-diversity differences amongst sites was tested on species abundances (Bray-Curtis distances) using the function betadisper from the package vegan in RStudio 12.1 (Posit team 2024). The network visualisation/analysis was performed using the function plotweb from the package bipartite (Dormann, Gruber, and Fruend 2008; Dormann et al. 2009).

3 Results

3.1 Hoverfly Floral-Visitor Components

The Syrphidae represented 3.4% of the overall recorded floral visits considering the four main orders of pollinators (Hymenoptera, Coleoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera), but 51% of the Diptera collected (Maestracci, Plume, and Gibernau 2024). Globally, the hoverfly family appears to be generalist visiting flowers from one-third of the plant community with a significant higher abundance on Foeniculum vulgare (see Section 3.5; Table S3). All the plant species visited by hoverflies were, in average, also visited by 10 other anthophilous insect families (range: 2 for the undetermined Poaceae to 25 for Foeniculum vulgare). Moreover, each hoverfly species appeared also to be generalist except probably for Eumerus basalis and Eristalinus taeniops (see Section 3.5). In terms of abundances, they represent < 20% of the total insect floral visitors for a given species (9% for Dittrichia vicosa, 12% for Foeniculum vulgare and 19% for Raphanus raphanistrum). Interestingly, they appear to be numerical important floral visitors in autumn (September to mid-November) almost equalling the Hymenoptera abundance (Maestracci, Plume, and Gibernau 2024; see Section 3.3).

3.2 Hoverfly Diversity and Richness

A total of 138 specimens were caught visiting flowers, representing 27 species from 16 genera (Table 2). The subfamily Syrphinae was the most diverse (9 genera, 13 species) compared to Milesinae (3 genera, 8 species) or Eristalinae (4 genera, 6 species). The seven most abundant species accounted for 67% of the abundance of the hoverfly community (Table 2), namely Eumerus barbarus (Coquebert, 1804) and Sphaerophoria scripta (Linnaeus, 1758) (19 specimens each), Chrysotoxum intermedium (15 specimens), Episyrphus balteatus De Geer, 1776 and Syritta pipiens (12 specimens each), Melanostoma mellinum (Linnaeus, 1758) (8 specimens) and Melanostoma scalare (Fabricius, 1794) (7 specimens). There was a high difference in abundance between the study sites, two-fold more hoverflies were collected at Loretto (65 individuals) than at Suartello (37 specimens) or Vignola (36 specimens). The compositional dominance was a bit lower in Loretto (D = 0.096) than in Suartello (D = 0.114) and Vignola (D = 0.127). In fact, the most abundant species per site represented 25% of the total floricolous hoverfly abundance at Loretto (Eumerus barbarus, N = 16) and at Vignola (Chrysotoxum intermedium, N = 10) and 30% at Suartello (Sphaerophoria scripta, N = 11).

| Subfamily | Species | Vignola | Loretto | Suartello | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syrphinae | Chrysotoxum intermedium Meigen, 1822 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 15 |

| Dasysyrphus albostriatus (Fallén, 1817) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Episyrphus balteatus De Geer, 1776 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 12 | |

| Eupeodes corollae (Fabricius, 1794) | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | |

| Melanostoma mellinum (Linnaeus, 1758) | 4 | 4 | 0 | 8 | |

| Melanostoma scalare (Fabricius, 1794) | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 | |

| Meliscaeva auricollis (Meigen, 1822) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Paragus bicolor (Fabricius, 1794) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Paragus haemorrhous Meigen, 1822 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Paragus quadrifasciatus Meigen, 1822 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Paragus sp1 Latreille, 1804a | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Sphaerophoria scripta (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 8 | 11 | 19 | |

| Syrphus ribesii (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Eristalinae | Eristalinus megacephalus (Rossi, 1794) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Eristalinus taeniops (Wiedemann, 1818) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |

| Eristalis similis (Fallén, 1817) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Eristalis tenax (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Helophilus pendulus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Myathropa florea (Linnaeus, 1758) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Milesinae | Eumerus barbarus (Coquebert, 1804) | 0 | 16 | 3 | 19 |

| Eumerus basalis Loew, 1848 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | |

| Eumerus pulchellus Loew, 1848 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Eumerus sp1 Fabricius, 1798a | 2 | 5 | 0 | 7 | |

| Merodon chalybeus Wiedemann in Meigen, 1822 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Merodon sp2 (Meigen, 1803)a | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Syritta pipiens (Linnaeus, 1758) | 7 | 3 | 2 | 12 | |

| Syritta sp1 (Lepeletier et Audinet-Serville, 1828)a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

- a Authors' names for unidentified species are related to the genus descriptor.

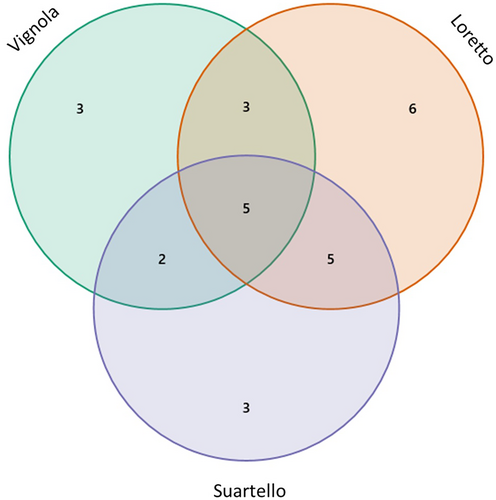

It is interesting to note that the diversity of hoverflies visiting flowers at the three sites studied was different, with 13 species at Vignola, 15 species at Suartello and 19 species at Loretto (Table 2). Accordingly, the Shannon index at Vignola (2.35) was lower than at Suartello (2.53) or Loretto (2.68). About half the species diversity was in common for any combination of two sites (between 7 and 10 species), and Loretto appeared to have a significant higher number of ‘exclusive’ species (6) than Suartello or Vignola (3 for both, Figure 2). The beta diversity comparisons (Harrison 2 measure) showed lower differences between Loretto and Suartello or between Loretto and Vignola (0.263 each), than between Suartello and Vignola (0.40). Those differences are probably partially explained by differences in the geographical characteristics, the main vegetation and the anthropic pressure of these three sites (Table 1, study site section) but also by differences in species diversity. The estimate of total species richness of flower-visiting hoverflies was between 28.2 and 26.9 at Loretto using both Chao1's unbiased or abundance-based coverage estimators, respectively. These estimates were lower for Suartello (24.1 and 24.8) or Vignola (19.8 and 25.3), suggesting that the potential diversity at Loretto, with 19 reported species, was better covered (~68%) than the two other sites (52%–60%).

3.3 Seasonal Variations

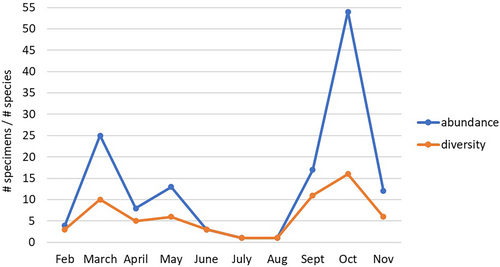

Both the abundance and the species diversity of anthophilous hoverflies underwent the same monthly variations with a bimodal pattern presenting a first peak in March and the second in November (Figure 3). At the studied sites, October proved to be the month with the most observations of floral hoverflies, both in terms of species diversity (16) and abundance of specimens (54; Figure 3). Hoverflies were most abundant in autumn since 60% of our captures took place between September and mid-November (Table S1, Figure 3). Not only the abundance but also the diversity was higher during this period since 19 species were recorded visiting flowers out of the total number of 28 (Figure 3). Note that 9 species (33%) were singletons (Table S1). With the exception of March, hoverflies were less frequently observed on flowers at the end of winter and during spring (second-half of February to June), with 4–13 individuals collected monthly representing only 3–6 species (Figure 3). In March, the second highest diversity and abundance of hoverflies visiting flowers was recorded with 10 species collected represented by 25 individuals. Summer months (July and August) were the poorest with only one hoverfly observed on flowers during each of them (Figure 3).

Now considering the monthly species composition, only two-third of the data are relevant since 9 out 27 recorded species were singletons (Table S1). They were collected throughout the year except in summer and particularly in spring (March: 3 singletons, April: 1, and May: 1) and autumn (September: 1, October: 2, and November: 1). Seven species were active all ‘year-round’ visiting flowers from February–March until October–November, namely Chrysotoxum intermedium, Episyrphus balteatus, Eumerus sp1, Eupeodes corollae (Fabricius, 1794), Meliscaeva auricollis (Meigen, 1822), Sphaerophoria scripta and Syritta pipiens. Five species were recorded on flowers from May–June to October–November, namely Eumerus barbarus, Eumerus basalis Loew, 1848, Paragus bicolor, Paragus haemorrhous Meigen, 1822 and Paragus quadrifasciatus Meigen, 1822. Finally, the last six species, were recorded visiting flowers during only one season, in spring (Melanostoma mellinum (Linnaeus, 1758), Melanostoma scalare and Eristalis tenax (Linnaeus, 1758)) or in autumn (Eristalinus taeniops, Paragus sp1 and Syrphus ribesii).

3.4 Daily Activity

Hoverflies' abundance and richness varied similarly amongst the three sites on daily-basis observations (Figure 4). Hoverflies were mostly observed on the flowers in the morning, particularly on early hours, rather than in the afternoon (Figure 4). The two time slots with the highest abundances of hoverflies were 09:00–10:00 h (37 specimens) and 11:00–12:00 h (27 specimens). In summary, 58% of all hoverfly specimens were collected during the morning hours (09:00–12:00 h) after 12:00 h between 9 and 14 specimens were collected per hour (Figure 4, Table S2).

In terms of diversity, the greatest number of hoverfly species (70%) was also collected during the morning hours (09:00–12:00 h). The species collected only in the afternoon, and mostly (6 out of 10) between 14:00 and 15:00 h, were in fact singletons (Table S2). Six species were active on flowers all day long and four other species had an extended period of floral visits continuous as Eristalinus taeniops (11:00–17:00 h) or ‘discontinuous’ with one capture both in the morning and the afternoon (Eristalis tenax, Eumerus pulchellus, Myathropa florea). The remaining six species appeared to have a more specific daily period for visiting flowers, especially in the morning for Eupeodes corollae, Melanostoma mellinum, Paragus quadrifasciatus or Eumerus basalis, at midday for Syrphus ribesii, or in the afternoon Paragus sp1.

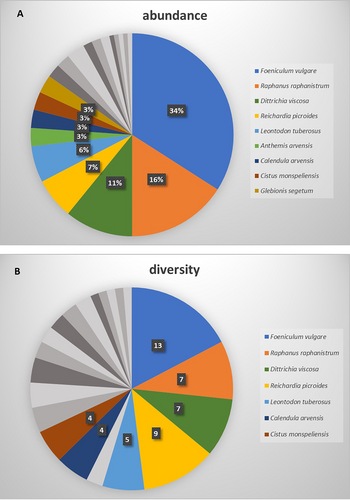

3.5 Diversity of Visited Flowers

We recorded a total of 21 angiosperm species visited by hoverflies during our study, distributed in 12 families (Table S3). The Asteraceae was by far the most diverse family visited by hoverflies with 10 species recorded, all the 11 other families were represented by one species each. The five most visited plants species, representing 73% of the total visit number, were Foeniculum vulgare (34%), Raphanus raphanistrum (16%), Dittrichia viscosa (11%), Reichardia picroides (7%) and Leontodon tuberosus (6%). Notable species were three daisies (Anthemis arvensis, Calendula arvensis, Glebionis segetum) and the rockrose Cistus monspeliensis (Figure 5A). In terms of species diversity, the same plant species listed above (minus Anthemis arvensis and Glebionis segetum) were also visited by a large number of hoverfly species (Figure 5B). In relation to the observed seasonal variation of both abundance and diversity of Syrphidae, flowering plants were visited by fewer hoverflies in spring and summer than in autumn (Foeniculum vulgare, Dittrichia viscosa, Reichardia picroides and Leontodon tuberosus) with the notable exception of Raphanus raphanistrum (May) (Table S3).

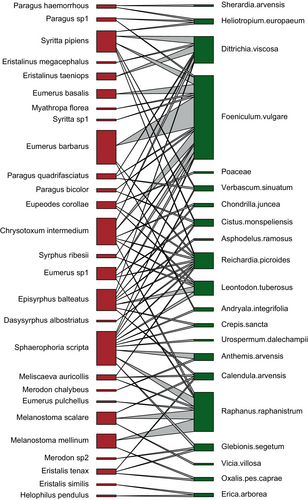

Interactions between hoverflies and flowering plants are highlighted on the bipartite network (Figure 6). Amongst the species present as singletons, four were captured on various Asteraceae (Anthemis arvensis, Dittrichia viscosa, Glebionis segetum and Reichardia picroides) and five on flowers of Foeniculum vulgare (2 spp.), Erica arborea (2 spp.) and Raphanus raphanistrum (1 sp) (Figure 6, Table S3). All these plant species were also visited by various other hoverfly species except the flowers of Erica arborea. Most of the remainder hoverfly species (18 spp.) behaved generalistically by visiting flowers from various plant species, particularly the most abundant ones (Figure 6). Sphaerophoria scripta visited mainly flowers of Raphanus raphanistrum (26% of the specimens) and Anthemis arvensis (16%) but also from nine other plant species belonging mainly to Asteraceae (7 spp.) (Figure 6). Episyrphus balteatus visited mainly flowers of Foeniculum vulgare (25%) and Leontodon tuberosus (25%) but also from six other species mainly Asteraceae (5 spp.). Chrysotoxum intermedium and Syritta pipiens, each visited flowers of six species with a higher number of visits on Dittrichia viscosa (20% and 33%, respectively) and Foeniculum vulgare (47% and 33%, respectively) (Figure 6, Table S3). Several species appeared to be oligolectic in our sampling. Melanostoma scalare and Melanostoma mellinum visited mainly flowers of Raphanus raphanistrum (88% and 71%, respectively) and only one or two others species (Figure 6). Melanostoma mellinum was the only hoverfly visiting Vicia villosa. Eumerus barbarus were mainly collected when visiting flowers of Foeniculum vulgare (89%), but this hoverfly species visited also in low frequency flowers from two other plant species (Figure 6). Finally, two species appeared to be specialist visitors in our sampling, Eristalinus taeniops on Dittrichia viscosa (4 specimens from Vignola) and Eumerus basalis on Foeniculum vulgare (5 specimens from Loretto and Suartello) but these results have to be confirmed considering the relative small sample sizes.

From the plant point of view, most of the plant species (76%) were visited by at least two hoverfly species. As mentioned before, four plants species (Foeniculum vulgare, Raphanus raphanistrum, Dittrichia viscosa and Reichardia picroides) were key floral resources since they were visited in total by 21 species representing 78% of the total observed hoverfly diversity (Figure 6). On the other hand, five plant species (Asphodelus ramosus, Sherardia arvensis, Urospermum dalechampii, Vicia villosa and an undetermined Poaceae) were each visited specifically by only one hoverfly species (Figure 6, Table S3).

4 Discussion

All the identified hoverfly species had already been reported from Corsica (Doczkal 1996; Touroult et al. 2020; Cornuel-Willermoz and Lebard 2024; Ichter et al. 2022; Mengual, Lebard, and Cornuel-Willermoz 2023) but 22 of them are reported here for the first time from the region of Ajaccio (Table 2). Three mentioned species previously reported from the Ajaccio region by the OCIC inventory were not recovered during our 9-months study, namely Chrysotoxum cisalpinum, Milesia semilectifera, Xylota segnis (Cornuel-Willermoz. A., pers. comm.), probably because of our less exhaustive sampling methods (O'Connor et al. 2019; Touroult et al. 2020). Interestingly, even if the vegetation of the three sites studied (Vignola, Suartello and Loretto) is a low maquis stratum, they present slightly different environments (vegetation stratum, proximity of woodland or the sea) which may explain partly the diversity patterns observed amongst the three studied sites. Specific species were found in each site representing between 20% and 32% of the site total species diversity (Figure 2). All these species were nonetheless rare in our sampling (1 or 2 specimens) suggesting that several of them may probably be found in the other sites with a more exhaustive sampling effort. The hoverfly community at Loretto not only appeared to be slightly more species-rich and abundant but also exhibited the lowest dominance despite the local abundance of Eumerus barbarus (e.g., 25% fo the hoverflies). Interestingly, this species which is abundant on two sites in our sampling (Table 2) has been only recently listed amongst 20 new reports for the island by la ‘Planète revisitée’—Corsican missions (Touroult et al. 2020). Finally, the three zones are more or less subject to anthropic impact linked to site management and certain activities, which can affect the diversity of hoverflies, in particular clear-cutting for mechanical maintenance (Maestracci. P-Y., pers. obsv.) but further studies are needed to measure such effects.

Our monthly diversity variations confirm for many species (Chrysotoxum intermedium, Episyrphus balteatus, Eumerus barbarus and Eumerus basalis, Syritta pipiens, Sphaerophoria scripta) what is already known of their activity period (Speight 2020). Interestingly, for three species (Paragus haemorrhous, Paragus quadrafasciatus and Eristalinus taeniops), we provide new information about their phenology extending their period of activity to October or mid-November (Speight 2020; Table S1). This might result from the mild autumn Mediterranean climate and its associated diverse flowering flora (Figure 3).

As our method recorded the visit of each sampled insect to a flower species, it allowed us to establish a list of local plants visited by the different anthophilous species of hoverflies and have an insight of their potential pollinator role. We documented several new visited plant families for as many as 13 hoverfly species (Speight 2020; Speight and Lebard 2021): Apiaceae and Asphodelaceae for Epysyrphus balteatus; Asteraceae for Chrysotoxum intermedium, Dasysyrphus albostriatus (Fallén, 1817) and Syrphus ribesii; Brassicaceae for Melanostoma scalare; Ericaceae for Eristalis similis and Oxalidaceae for Eristalis tenax (Table S4). Two new visited-plant families are here reported for the two common species, Syritta pipiens (Apiaceae and Boraginaceae) and Melanostoma mellinum (Brassicaceae and Oxalidaceae). For the genus Paragus (P. bicolor, P. haemorrhous, P. quadrifasciatus and P. sp1), three new visited-plant families are added: Boraginaceae, Cistaceae and Rubiaceae. Finally, the flowers visited by Merondon chalybeus are not known (Speight 2020); however, our unique record for this species was realised on a flower of Asteraceae (Anthemis arvensis, Table S4). Almost all the hoverfly species appeared to be generalist visiting flowers from up to 11 plants species, note that most of the species recorded visiting two or three plant species were in fact rare in our sampling and only recorded once per species (Tables S3 and S4). On the other hand, two species appeared to be specialist Eumerus basalis on Foeniculum vulgare and Eristalinus taeniops on Dittrichia viscosa (Vignola) (Table 2, Table S4).

5 Conclusion

The diversity of hoverflies at the three studied low shrubland sites (Loretto, Suartello and Vignola) was relatively high with some differences. However, Loretto stands out from the other two sites with both a greater species diversity and abundance of hoverflies recorded visiting flowers. In terms of diversity, Syrphinae appeared to be the most diverse subfamily (13 spp.), representing half of the family diversity in our study sites. With regard to diel activity patterns, flower visits by hoverflies occurred mainly during the morning at the three sites. Hoverflies showed a marked seasonality since most records of flower occurred in Autumn (from September to November). In addition, the Asteraceae was the plant family most visited by hoverflies (Dittrichia viscosa, Crepis sancta, Leontodon tuberosus, Reichardia picroides, Anthemis arvensis, Chondrilla juncea and Calendula arvensis). The two most abundant species were Sphaerophoria scripta (Syrphinae) and Eumerus barbarus (Milesinae). The first species is a common generalist hoverfly visiting flowers from 11 different species on our study sites. On the other hand, the abundance of Eumerus barbarus may be in relation to its larval biology, which is not insectivore but phytophagous on bulbs or roots of plants from the Asparagales order (Van Steenis, Hauser, and van Zuijen 2017), such as the branched asphodel (Asphodelus ramosus, L., 1753), which is abundant in all the study sites. Further studies on hoverfly biology are necessary to better understand their distribution and ecology. Finally, it should be noted that most of these data are new for the Ajaccio region, with the exception of the limited records of the OCIC (Cornuel-Willermoz and Lebard 2024). Despite hoverflies being recognised as important pollinators, both for crops and wildflowers, our study underlines that their ecology and their role in plant-pollinator networks are still poorly known in ‘natural’ habitats. It appears that they are likely generalist pollinators, visiting flowers from various plant species, particularly the most abundant. Their pollination efficiency remains to be properly studied. Their high abundances in autumn also suggest that they are key floral visitors for late-flowering species and probably also for some fall agricultural plantings. Hoverflies represent hence interesting bio-indicators to measure landscape manage effects of natural zones of maquis for conservation purposes in the context of a mitigation hierarchy.

Author Contributions

Laurent Plume: investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. Pierre-Yves Maestracci: investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, data curation, methodology. Marc Gibernau: conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, validation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgements

We thank Véronique Sarthou for her help in identifying certain specimens and two anonymous reviewers for their improvements and constructive comments on the manuscript. The study was funded by the project CPER No. 40137 “BiodivCorse—Explorer la biodiversité de la Corse” (Collectivité de Corse—Ministère de la Cohésion du territoire et des Relations avec les Collectivités territoriales). Financial supports were provided to Laurent Plume by the University of Corsica through its doctoral programme and to Pierre-Yves Maestracci through the CIFRE doctoral programme of the ANRT (No. 2022/0393) between the ENGIE—Lab CRIGEN, The University Pantheon-Assas Paris and the University of Corsica.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10781143.