Association of Periodontal Condition With Serum C-Reactive Protein Levels: The Role of Serum Apolipoproteins' Concentration

Funding: This work was supported by the Finnish Association of Women Dentists; Suomen Hammaslääkäriseura Apollonia.

ABSTRACT

Aim

To investigate whether the systemic inflammatory response against inflammatory conditions in the periodontium is related to serum apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and A1 (ApoA1) concentrations.

Material and Methods

The study consisted of the Health 2000 Survey participants (n = 2709) aged 30–49 years. The inflammatory condition of the periodontium was assessed by means of the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) and deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets. Systemic inflammation was measured by serum C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. The role of ApoB and ApoA1 was studied by performing regression analyses and stratified analyses (according to the median values).

Results

In logistic regression analyses, the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets was associated with serum CRP levels among those participants whose serum ApoB concentration was ≥ 1.12 g/L. When the participants' ApoB concentration was < 1.12 g/L, such an association between deepened periodontal pockets and CRP was not observed. The direction or strength of the association between periodontal pockets and CRP was not essentially different in the ApoA1 strata.

Conclusion

Systemic response against poor periodontal condition varied between individuals. The variation appeared to be related more to the serum concentration of ApoB than ApoA1.

1 Introduction

Evidence from non-experimental and experimental studies suggests that defence mechanisms against periodontal pathogens cause both local and systemic inflammatory responses (Luthra et al. 2022; Paraskevas et al. 2008). The strength of the inflammatory response, known as low-grade inflammation, appears to vary between individuals. Previous studies have shown that there is individual variation in response to periodontal treatment even in randomised controlled trials (Raittio et al. 2024). The reason for the variation is not known, but it has been found that the variation can be attributed to behavioural, environmental and genetic factors. These include smoking, conditions such as poor nutritional status, obesity, diseases and the participants' medications, as well as predisposing genes (Furman et al. 2019).

We have previously reported that the systemic inflammatory response related to a bacterial challenge in the periodontium, measured either by serum C-reactive protein (CRP) (Haro et al. 2012) or interleukin-6 (IL-6) (Haro et al. 2017), was related to the serum lipid composition. This was seen in the case of both low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels. However, it was not known whether this observed variation in the systemic inflammatory response was related to serum lipid composition, that is, HDL-C and LDL-C levels as such, or its components, or other related factors such as systemic factors or individual characteristics.

One potential biological factor that could explain the above-mentioned findings, that is, variation in systemic inflammatory response between individuals related to the serum lipid composition, could be the differences in the apolipoprotein structures of lipoproteins. The main apolipoprotein of LDL particles is apolipoprotein B (ApoB) and that of HDL is apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1). Of these, ApoB enhances the inflammatory response (Assinger et al. 2011; Bovenberg et al. 2010), whereas ApoA1 has many anti-inflammatory properties, as it down-regulates the inflammatory response through several mechanisms (Berbee et al. 2005; Chiesa and Charakida 2019). Based on these pro- or anti-inflammatory properties of apolipoproteins, we hypothesised that the serum apolipoprotein constitution explains the observed variation in the systemic inflammatory response. Consequently, this study aimed to examine whether the systemic response to an inflammatory condition of the periodontium, measured by the number of teeth with periodontal pockets ≥ 4 mm deep, is modified by the serum ApoB and ApoA1 concentration.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

The present study uses the data from the nationally representative Health 2000 Survey, conducted by the National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) (formerly National Public Health Institute [KTL] of Finland). During the years 2000 and 2001, 8028 participants—aged 30 years or older, living in mainland Finland—were invited to participate in the survey. Of these, 79% participated in at least one phase of the survey. Data collection consisted of a clinical health examination, including an oral examination, in addition to laboratory analyses, imaging studies, interviews and questionnaires (Aromaa and Koskinen 2004; Suominen-Taipale et al. 2008).

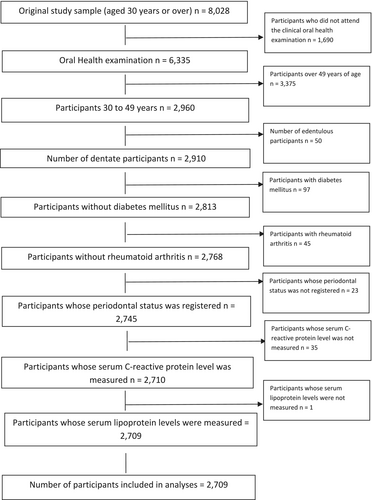

The study population consisted of a subpopulation of 30–49-year-old, dentate, non-diabetic, non-rheumatic participants, whose periodontal status was registered and whose serum concentration of CRP was measured (n = 2709). A flow chart explaining the formation of the study population is presented in Figure 1, and a detailed description is provided in Appendix A.

The Ethical Committee for Epidemiology and Public Health of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the study protocol of the Health 2000 Survey. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Details of the Health 2000 Survey are available at http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201204193320. The study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association [WMA] 1976) and based on the guidelines developed by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative (von Elm et al. 2007).

2.2 Outcome Variable

The serum CRP concentrations were quantified using an automated analyser (Optima, Thermo Electron Oy, Vantaa, Finland) and an ultrasensitive immunoturbidimetric test (Ultrasensitive CRP, Orion Diagnostica, Espoo, Finland). For statistical analyses, the participants were categorised into two groups using a commonly used cut-off value of 3 mg/L (CRP < 3 mg/L vs. CRP ≥ 3 mg/L) (Pearson et al. 2003).

2.3 Explanatory Variables

The number of teeth with deepened (probing pocket depth [PPD] ≥ 4 mm) and deep (PPD ≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets served as the explanatory variables. The former was categorised as follows: 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–11 and ≥ 12. The latter was classified into four categories: 0, 1–3, 4–6 and ≥ 7. Both explanatory variables were also used as continuous variables. A detailed description of the periodontal examination is given in Appendix A.

2.4 Other Variables

The confounding factors were selected a priori according to current knowledge about factors related to CRP. These include age, gender, education, body mass index (BMI), the serum concentrations of ApoB and ApoA1, serum levels of triglycerides, use of a lipid-lowering medication, physical activity and smoking habits. Measurements of these variables are detailed in Appendix A.

2.5 Statistical Methods

Because of the two-stage cluster sampling design used in the Health 2000 Survey, weights based on post-stratification with gender, age and region were used. Odds ratios (ORs) and beta-estimates with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using logistic and linear regression models, respectively. Interaction (effect modification) of ApoA1 and ApoB was studied by adding a product term into the adjusted logistic and linear regression models.

Stratified analyses were performed according to the median values of the serum ApoB (1.12 g/L) and ApoA1 (1.55 g/L) values. Missing data were addressed by creating an extra category ‘missing information’ (the use of lipid-lowering medication), and otherwise by excluding participants with missing data in any of the variables from multivariate analyses. The data analyses were performed using SAS Callable SUDAAN software (Release 11.0.0, Research Triangle Institute, Raleigh, NC, USA).

3 Results

The basic characteristics of the study population according to the serum CRP levels (CRP < 3 mg/L vs. CRP ≥ 3 mg/L) are shown in Table 1 and those according to ApoB and ApoA1 (median values for ApoB 1.12 g/L and ApoA1 1.55 g/L) in Table 2. The Pearson correlation coefficient between ApoB and ApoA1 in these data was −0.07.

| CRP < 3.0 mg/L (n = 2,365) | CRP ≥ 3.0 mg/L (n = 344) | Total (n = 2,709) | p a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) (n = 2709) | 39.9 (0.1) | 39.3 (0.3) | 39.8 (0.1) | 0.083 |

| Gender (%) (n = 2709) | 0.063 | |||

| Male | 50.7 | 45.6 | 50.1 | |

| Female | 49.3 | 54.4 | 49.9 | |

| Educational level (%) (n = 2708) | 0.043 | |||

| Basic | 17.5 (0.9) | 22.3 (2.3) | 18.1 (0.8) | |

| Intermediate | 41.8 (1.0) | 43.2 (2.6) | 41.2 (1.0) | |

| Higher | 40.7 (1.0) | 34.4 (2.6) | 39.9 (0.9) | |

| Body mass index (BMI) (n = 2708) | ||||

| BMI (mean) | 25.5 (0.1) | 28.5 (0.3) | 25.9 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| Proportion of normalweight participants (%) | 49.8 (1.0) | 28.3 (2.2) | 47.1 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| Proportion of overweight participants (%) | 38.0 (1.0) | 37.4 (2.5) | 37.9 (0.9) | 0.826 |

| Proportion of obese participants (%) | 12.3 (0.6) | 34.4 (2.3) | 15.0 (0.7) | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides mmol/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.4 (0.02) | 1.8 (0.07) | 1.5 (0.02) | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C mmol/L (mean) (n = 2699) | 3.6 (0.02) | 3.5 (0.06) | 3.5 (0.02) | 0.323 |

| LDL-C 3.4 mmol/L or more (%) | 52 (1.3) | 49 (2.5) | 51 (1.2) | 0.374 |

| HDL-C mmol/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.4 (0.01) | 1.3 (0.02) | 1.3 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C 1.3 mmol/L or more (%) | 51 (1.1) | 38 (2.5) | 50 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| ApoB g/L (mean) (n=2709) | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.2 (0.02) | 1.2 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| ApoA1 g/L (mean) (n=2,709) | 1.6 (0.01) | 1.6 (0.02) | 1.6 (0.01) | 0.788 |

| Use of lipid-lowering medication (%) (n = 2709) | ||||

| Yes (%) | 1.2 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.2) | 0.010 |

| No (%) | 90.0 (0.7) | 88.9 (1.8) | 89.8 (0.7) | |

| Missing information | 8.9 (0.7) | 10.8 (1.8) | 9.1 (0.7) | |

| Level of physical activity (%) (n = 2685) | ||||

| Sufficient | 30.0 (0.9) | 25.3 (2.5) | 29.4 (0.9) | 0.049 |

| Intermediate | 31.6 (1.0) | 29.6 (2.6) | 31.4 (0.9) | |

| Sedentary | 38.4 (1.0) | 45.1 (2.7) | 39.2 (0.9) | |

| Smoking habits/history (%) (n = 2704) | 0.022 | |||

| Non-smokers | 64.4 (1.0) | 56.6 (2.9) | 63.4 (1.0) | |

| Occasional smokers | 8.3 (0.7) | 8.8 (1.6) | 8.3 (0.6) | |

| Daily smokers | 27.3 (0.9) | 34.6 (2.6) | 28.3 (0.9) | |

| Number of teeth (mean) (n = 2709) | 26.6 (0.1) | 26.3 (0.2) | 26.5 (0.1) | 0.366 |

| Periodontal condition (n = 2709) | ||||

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets (mean) | 3.6 (0.2) | 4.5 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.2) | 0.008 |

| Participants without deepened periodontal pockets (%) | 41.3 (1.8) | 37.5 (2.7) | 40.8 (1.7) | 0.126 |

| Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets (mean) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0) | 0.015 |

| Participants without deep periodontal pockets | 86.9 (0.8) | 82.7 (2.1) | 86.3 (0.8) | 0.045 |

- a Chi-square test for categorised and t-test for continuous variables.

| ApoB < 1.12 mmol/L (n = 1341) | ApoB ≥ 1.12 mmol/L (n = 1368) | ApoA1 < 1.55 mmol/L (n = 1389) | ApoA1 ≥ 1.55 mmol/L (n = 1320) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) (n = 2709) | 38.7 (0.2) | 40.8 (0.2) | 39.3 (0.2) | 40.3 (0.1) |

| Gender (%) (n = 2709) | ||||

| Male | 35.7 (1.3) | 63.6 (1.4) | 59.3 (1.3) | 41.1 (1.4) |

| Female | 64.3 (1.3) | 36.4 (1.4) | 40.7 (1.3) | 58.9 (1.4) |

| Educational level (%) (n = 2708) | ||||

| Basic | 14.9 (1.0) | 21.1 (1.3) | 17.5 (1.1) | 18.7 (1.1) |

| Intermediate | 38.1 (1.4) | 45.6 (1.4) | 42.6 (1.5) | 41.3 (1.6) |

| Higher | 47.0 (1.5) | 33.2 (1.2) | 39.9 (1.5) | 39.9 (1.3) |

| Body mass index (%) (n = 2708) | ||||

| Proportion of normalweight | 62.7 (1.4) | 32.4 (1.2) | 40.8 (1.4) | 53.2 (1.3) |

| Proportion of overweight | 29.6 (1.3) | 45.7 (1.3) | 40.0 (1.4) | 35.8 (1.2) |

| Proportion of obese | 7.7 (0.7) | 21.9 (1.1) | 19.2 (1.1) | 11.0 (0.9) |

| Triglycerides mmol/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.0 (0.02) | 1.9 (0.04) | 1.6 (0.03) | 1.4 (0.02) |

| LDL-C mmol/L (mean) (n = 2699) | 2.8 (0.02) | 4.2 (0.03) | 3.6 (0.03) | 3.5 (0.03) |

| HDL-C mmol/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.5 (0.01) | 1.2 (0.01) | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.6 (0.01) |

| ApoB g/L (mean) (n=2709) | 0.9 (0.00) | 1.4 (0.01) | 1.1 (0.01) | 1.2 (0.01) |

| ApoA1 g/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.6 (0.01) | 1.6 (0.01) | 1.4 (0.00) | 1.8 (0.01) |

| CRP mg/L (mean) (n = 2709) | 1.3 (0.08) | 1.7 (0.08) | 1.6 (0.09) | 1.4 (0.08) |

| Use of lipid-lowering medication (%) (n = 2709) | ||||

| Yes | 0.5 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) |

| No | 91.1 (0.9) | 88.5 (1.0) | 88.5 (1.0) | 91.0 (0.8) |

| Missing | 8.4 (0.8) | 9.8 (0.9) | 10.2 (1.0) | 8.0 (0.8) |

| Level of physical activity (%) (n = 2685) | ||||

| Sufficient | 32.6 (1.3) | 26.3 (1.2) | 26.1 (1.4) | 32.6 (1.2) |

| Intermediate | 31.8 (1.4) | 30.9 (1.3) | 32.0 (1.3) | 30.8 (1.3) |

| Sedentary | 35.6 (1.3) | 42.7 (1.3) | 42.0 (1.3) | 36.6 (1.2) |

| Smoking habits/history (%) (n = 2704) | ||||

| Non-smokers | 66.0 (1.4) | 60.9 (1.4) | 60.1 (1.5) | 66.7 (1.3) |

| Occasional smokers | 8.3 (0.7) | 8.4 (0.8) | 7.5 (0.7) | 9.1 (0.8) |

| Daily smokers | 25.7 (1.3) | 30.7 (1.2) | 32.4 (1.4) | 24.2 (1.1) |

| Number of teeth (mean) (n = 2709) | 26.9 (0.1) | 26.2 (0.1) | 26.6 (0.1) | 26.4 (0.1) |

| Periodontal condition (n = 2709) | ||||

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets (mean) | 3.1 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.2) |

| Participants without deepened periodontal pockets (%) | 45.6 (2.0) | 36.3 (2.0) | 40.0 (2.0) | 41.6 (2.0) |

| Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets (mean) | 0.3 (0.0) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.0) |

| Participants without deep periodontal pockets (%) | 90.0 (0.9) | 82.9 (1.1) | 85.2 (1.1) | 87.4 (1.0) |

In both the logistic and the linear regression models, adjusted for confounding factors, the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets was weakly and somewhat inconsistently associated with the serum CRP level (Tables 3 and 4). The number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets was associated more strongly with CRP than the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets (Tables 3 and 4).

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets | Serum CRP level ≥ 3.0 mg/L | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI)a | Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets | OR (95% CI)a | |

| 0 | 1.0 | 0 | 1.00 |

| 1–3 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1–3 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) |

| 4–6 | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 4–6 | 1.0 (0.3–2.9) |

| 7–11 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | ≥ 7 | 2.8 (1.2–6.1) |

| ≥ 12 | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | ||

| Continuous variable | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | Continuous variable | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) |

- a Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoB (continuous variable), serum ApoAl (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity and smoking. Effective n = 2682.

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets | Serum CRP level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Coefficient (95% CI)b | Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets | β-Coefficient (95% CI)b | |

| 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| 1–3 | 0.009 (–0.016 to 0.036) | 1–3 | 0.013 (–0.018 to 0.046) |

| 4–6 | –0.005 (–0.036 to 0.026) | 4–6 | 0.031 (–0.057 to 0.119) |

| 7–11 | 0.019 (–0.018 to 0.056) | ≥ 7 | 0.091 (0.018 to 0.165) |

| ≥ 12 | 0.041 (0.003 to 0.079) | ||

| Continuous variable | 0.002 (0.000 to 0.004) | Continuous variable | 0.006 (–0.000 to 0.012) |

- a Log-transformed value.

- b Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoB (continuous variable), serum ApoA1 (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity and smoking. Effective n = 2682.

In the stratified analyses, when the serum ApoB concentration was < 1.12 g/L, there was no positive association between the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets and the serum CRP level (continuous variables). However, when the serum ApoB concentration was ≥ 1.12 g/L, a positive association existed between the number of teeth with deepened periodontal pockets and elevated serum CRP levels (Tables 5 and 6). The p value for the product term obtained from the linear regression model for the continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 4 mm) and ApoB was 0.059. A similar pattern was observed in the case of deep periodontal pockets: a positive association existed between the number of teeth with deep periodontal pockets and elevated serum CRP levels when the ApoB concentration was ≥ 1.12 g/L, while no association—or in some cases even an inverse association—was observed when the ApoB concentration was < 1.12 g/L. The p value for the product term for the continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm) and ApoB was 0.301 (Tables 5 and 6).

| Serum CRP level ≥ 3.0 mg/L | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoB < 1.12 g/L | ApoB ≥ 1.12 g/L | ApoA1 < 1.55 g/L | ApoA1 ≥ 1.55 g/L | |

| Effective n = 1327 | Effective n = 1355 | Effective n = 1306 | Effective n = 1376 | |

| ORa (95% CI) | ORa (95% CI) | ORb (95% CI) | ORb (95% CI) | |

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1–3 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) |

| 4–6 | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 1.0 (0.6–1.8) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 1.2 (0.6–2.2) |

| 7–11 | 0.9 (0.5–1.9) | 1.3 (0.9–2.1) | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

| ≥ 12 | 0.7 (0.3–1.7) | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | 1.3 (0.7–2.1) | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) |

| Continuous variable | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 1.02 (1.00–1.05) | 1.02 (0.99–1.06) |

| p value for product term for categorised pocket teeth variable (probing pocket depth [PPD] ≥ 4 mm) and ApoB: 0.655. | ||||

| p value for product term for categorised pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 4 mm) and ApoA1: 0.762. | ||||

| Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets | ||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 1–3 | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 0.9 (0.6–1.6) | 1.5 (0.8–2.6) |

| 4–6 | 0.7 (0.1–5.0) | 1.1 (0.3–4.1) | 1.0 (0.2–3.8) | 1.2 (0.3–5.9) |

| ≥ 7 | 0.6 (0.1–5.5) | 4.3 (1.7–10.5) | 3.6 (1.5–8.6) | 2.0 (0.5–7.9) |

| Continuous variable | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 1.13 (1.05–1.22) | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 1.06 (0.95–1.19) |

| p value for product term for categorised pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm) and ApoA1: 0.396. | ||||

| p value for product term for categorised pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm) and ApoB: 0.462. | ||||

- a Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoA1 (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity, and smoking.

- b Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoB (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity, and smoking.

| Serum CRP level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApoB < 1.12 g/L | ApoB ≥ 1.12 g/L | ApoA1 < 1.55 g/L | ApoA1 ≥ 1.55 g/L | |

| Effective n = 1327 | Effective n = 1355 | Effective n = 1306 | Effective n = 1376 | |

| β-Coefficient (95% CI)b | β-Coefficient (95% CI)b | β-Coefficient (95% CI)c | β-Coefficient (95% CI)c | |

| Number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets | ||||

| 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1–3 | –0.007 (–0.042 to 0.028) | 0.028 (–0.010 to 0.066) | 0.021 (–0.019 to 0.061) | 0.001 (–0.029 to 0.030) |

| 4–6 | –0.023 (–0.067 to 0.021) | 0.013 (–0.031 to 0.056) | -0.007 (–0.049 to 0.034) | -0.004 (–0.054 to 0.046) |

| 7–11 | –0.002 (–0.055 to 0.051) | 0.040 (–0.009 to 0.089) | 0.037 (–0.019 to 0.094) | 0.010 (–0.038 to 0.057) |

| ≥ 12 | –0.012 (–0.068 to 0.044) | 0.077 (0.025 to 0.128) | 0.042 (–0.009 to 0.093) | 0.038 (–0.021 to 0.010) |

| Continuous variable | –0.000 (–0.003 to 0.002) | 0.004 (0.002 to 0.007) | 0.003 (0.000 to 0.005) | 0.002 (–0.001 to 0.005) |

| p value for product term for continuous pocket teeth variable (probing pocket depth [PPD] ≥ 4 mm) and ApoB: 0.059. | ||||

| p value for product term for continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 4 mm) and ApoA1: 0.679. | ||||

| Number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets | ||||

| 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 1–3 | 0.001 (–0.057 to 0.060) | 0.022 (–0.018 to 0.061) | –0.011 (–0.053 to 0.030) | 0.038 (–0.013 to 0.089) |

| 4–6 | –0.023 (–0.148 to 0.103) | 0.056 (–0.061 to 0.173) | 0.061 (–0.057 to 0.180) | –0.010 (–0.117 to 0.096) |

| ≥ 7 | 0.037 (–0.067 to 0.141) | 0.117 (0.017 to 0.216) | 0.010 (0.017 to 0.182) | 0.090 (–0.025 to 0.206) |

| Continuous variable | –0.002 (–0.011 to 0.007) | 0.010 (0.002 to 0.018) | 0.006 (–0.001 to 0.012) | 0.006 (–0.003 to 0.016) |

| p value for product term for continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm) and ApoB: 0.301. | ||||

| p value for product term for continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm) and ApoA1: 0.924. | ||||

- a Log-transformed value.

- b Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoA1 (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity and smoking.

- c Adjusted for age (continuous variable), gender, education, BMI (continuous variable), triglycerides (continuous variable), serum ApoB (continuous variable), lipid medication, physical activity and smoking.

In the case of ApoA1, risk estimates (ORs and beta-estimates) were above 1 in both groups of ApoA1, and risk estimates from regression models using continuous explanatory variables were identical in most cases (Tables 5 and 6). When stratified by serum ApoA1 concentration, no essential modification was visually observed, and the p value for product terms for ApoA1 interaction obtained from linear regression was 0.679 for the continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 4 mm) and 0.924 for the continuous pocket teeth variable (PPD ≥ 6 mm).

4 Discussion

One of the main findings of this study was that the systemic inflammatory response associated with the inflammatory condition in the periodontium varied according to the serum ApoB concentration. This finding is in line with our hypothesis and in congruence with our previous studies (Haro et al. 2012, 2017), where we reported that the strength of the systemic inflammatory response to poor periodontal condition, measured by the number of teeth with periodontal pockets, was related to the serum LDL-C level. The observation that the systemic response varied according to the serum ApoB concentration is not surprising from the biological point of view either, because earlier studies have suggested that certain elements of ApoB are in charge of the inflammatory properties of LDL (Ketelhuth et al. 2011) and because ApoB is also known to reside in the LDL particles at a ratio of one molecule per lipoprotein particle and is thus considered a marker of the number of LDL particles (Dominiczak and Caslake 2011).

The other important finding was that the strength of the association between the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets and the serum CRP level appeared to be largely unaffected by the ApoA1 level. This finding appears to go against our hypothesis and, in a way, in contradiction with the results of our previous study, where we found that a systemic response to inflammation in the periodontium seemed to be more pronounced among those with a low serum HDL-C level (HDL-C < 1.3 mmol/L) (Haro et al. 2012). The findings of the present study suggest that the previously observed seemingly anti-inflammatory effects of HDL may be attributable to properties other than those related to ApoA1. It could be hypothesised that these relate to the anti-inflammatory effects of HDL, such as reverse cholesterol transport and the ability to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation, for instance (Chiesa and Charakida 2019).

The presence of causal interdependency, that is, synergism and antagonism effects, was studied using statistical methods (adding product terms in both multiplicative and additive regression models). The interpretation of these interaction models (i.e., the statistically suggestive p value for the product term of the continuous pocket teeth variable [PPD ≥ 4 mm] and ApoB in the additive models) is in line with the observations in the estimates in the stratified analyses, suggesting the presence of a biological interaction of ApoB. However, because of the extremely skewed distribution of CRP and the following log-transformation of CRP before fitting the linear regression models, caution is advised when interpreting the regression models with the continuous CRP (Table 6). In addition, the small number of participants in the categories of the explanatory variable (especially in the number of teeth with deep periodontal pockets) obviously affects the p values, and any interpretation of an interaction between categorical periodontal pocket variables and the components of lipoproteins (ApoB and ApoA1) should likewise be made with caution (Table 6).

Especially in the stratified analyses, there were some deviations from the exposure–response pattern in risk estimates, which may be associated with chance variation. Chance variation may be related to methodological aspects such as poor quality in the measurement of periodontal pockets. In addition, chance variation relates to the small number of participants in some categories of the explanatory variables. The unequal number of participants and the small number of participants in the categories of the explanatory variables (the number of teeth with periodontal pocket variables) were in turn partly due to the fact that we used the same categories as in the previous studies (Haro et al. 2012, 2017). In addition, the said deviations could also be due to possible overlap between the ApoA1 and ApoB groups.

An alternative explanation for the observed synergy is that serum ApoB does not modify the association between periodontitis and systemic inflammation; instead, a high serum ApoB concentration reflects other factors that are associated with an increased susceptibility to inflammatory diseases or conditions.

5 Strengths and Limitations

We were able to restrict the originally quite large nationally representative study population to a homogeneous dataset consisting of 30- to 49-year-old non-diabetic and non-rheumatic participants. We did this to reduce confounding, which could result from non-oral diseases with an inflammatory component, medications, age-related habitual changes in body composition and the lack of physical exercise, for example. Owing to the restrictions and possibly quite good general health, the proportion of participants with CRP > 10 mg/L was less than 2% of all the participants, meaning that poor general health was unlikely to have caused any essential bias.

Individuals with the most common diseases associated with periodontitis, namely diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis, were excluded from the data (Figure 1). The reason for excluding individuals with these conditions was that they both associate with periodontitis and a systemic inflammatory condition. Moreover, the operationalisation of such diseases poses challenges because constructing a variable in a way that would accurately take into account the type and severity of the disease, and possible medications (often having anti-inflammatory properties), is not possible. Because of this and because the overall number of individuals with diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis was small, they were—from the point of view of validity—excluded from the dataset.

The operationalisation of body weight was done using BMI, even though it has well-known disadvantages because it does not take into account body composition or the proportion of body fat. However, unlike in the case of diabetes, for instance, overweight and obesity can be clearly defined numerically and can be used both as categorical and continuous variables.

In addition to the above restrictions, we reduced confounding by means of multivariate models. We used covariates that can be expected to be associated with CRP based on a priori knowledge and that have been previously found to be unevenly distributed in the categories of periodontal pocket teeth variables in the Health 2000 Survey data (Ollikainen et al. 2014). However, as in all non-experimental studies, despite the use of a large set of covariates, residual confounding might exist. This could relate to unmeasured, unoperationalised and thus uncontrollable variables, or inappropriate categorisation of the variables used in the study.

Periodontal pocket measurements were made on four predetermined sites of each tooth and only the deepest measurement on each tooth was recorded, which in some cases has underestimated the extent of inflammation. However, this underestimation is not substantial in most cases, because in this study population the average number of teeth with deepened and deep periodontal pockets was fairly low, as most participants had either none or at most one tooth with a periodontal pocket of PPD ≥ 4 mm.

Another shortcoming related to the measurement of the inflammatory condition of the periodontium was that we were not able to combine the tooth-level data of pocket depth with the data of periodontal parameters such as bleeding on probing or attachment loss, because of the absence of these measurements at the tooth level. Despite being an evident shortcoming, the significance of this is likely to be relatively small, as earlier studies have shown that pocket depth alone indicates the presence of periodontal inflammatory condition fairly well (Demmer et al. 2010; Page and Eke 2007).

In the Health 2000 Survey, quality procedures were used to standardise the measurements and subsequently to reduce individual variation between examiners, as well as to assess the quality of the data. Regarding pocket depth measurements, intra-examiner kappa values in the Health 2000 Survey were fairly high, indicating high reproducibility, but the results of the inter-examiner measurements and subsequent analyses showed that field examiners reported fewer findings than the reference examiner (Vehkalahti et al. 2008). This may lead to bias towards zero, indicating that the observed risk estimates are conservative.

There are some limitations related to apolipoproteins, too. In the case of the categorisation of apolipoproteins, we used median values obtained from a representative sample of the Finnish adult population aged 30–49 years (for ApoB 1.12 g/L and for ApoA1 1.55 g/L). However, it is possible that these might not be the optimal cut-off values for ApoB and ApoA1 from the biological point of view. It is also possible that the ratio ApoB:ApoA1 would better describe the modifying effect of proinflammatory versus anti-inflammatory capacity in the association between periodontal condition and systemic inflammation.

Lastly, it should be kept in mind that the study had a cross-sectional study design. This means that we cannot make any conclusions on the temporal sequence between periodontal condition, inflammatory condition and apolipoprotein composition.

6 Implications of the Study

From a clinical perspective, it can be speculated that guiding individuals with periodontal diseases towards a healthy lifestyle, including weight control and a balanced diet, would be beneficial. Anti-inflammatory medications may also be beneficial from an inflammatory perspective, although their use is not indicated for the treatment of periodontal diseases. All these could prevent or reduce the development of systemic low-grade inflammation related to the infectious and inflammatory conditions of the periodontium.

From a research perspective, the systemic effect of periodontal treatment should be studied using stratification methods according to the study participants' inflammatory status. It is possible to speculate that the inflammatory status may be a cause for the variation observed in studies focusing on the effect of periodontal treatment on the glycaemic equilibrium and CRP levels. Such variation may also occur in connection with diseases and conditions other than periodontitis. Naturally, the inflammatory status may also be treated as an effect-modifying factor in non-experimental studies.

7 Future Perspectives

It was observed that the modifying effect of LDL (Haro et al. 2012) was slightly stronger than ApoB, meaning that LDL is a more important determinant than ApoB in determining the systemic reaction. In relation to what is known from the field of cardiology, it is against expectations because apolipoprotein assays are generally considered to be more effective in cardiovascular risk assessment than cholesterol-based assays (Leiviska et al. 2011). Nevertheless, it is essential to emphasise that the difference in the modifying effect between LDL and ApoB in the periodontal condition–CRP association was not substantial.

Based on this minor difference in the modifying effects of LDL and ApoB, we can speculate that the qualitative aspects, such as the size of LDL particles, may also play an important role. It has been suggested earlier that the LDL-C:ApoB ratio reflects the size of LDL particles, and it has been observed that small, dense LDL particles are particularly atherogenic, as they are able to penetrate vessel walls effectively (Berneis and Krauss 2002). Not surprisingly, the LDL-C:ApoB ratio has been associated with cardiovascular events (Drexel et al. 2021). Whether the LDL-C:ApoB ratio modifies the association between periodontal condition and systemic inflammation remains to be investigated in future studies.

When comparing the modifying effect of HDL (Haro et al. 2012) and its main apolipoprotein ApoA1, it was observed that the modifying effect of HDL exists, whereas it is missing in the case of ApoA1. This finding suggests that properties of HDL beyond those related to ApoA1 are important in determining the systemic response to inflammation in the periodontium. The role of other factors related to HDL remains to be studied.

8 Concluding Remarks

This is a continuation of our earlier works where we reported that LDL and HDL levels were associated with a systemic response against inflammation in the periodontium (Haro et al. 2012, 2017). In this subsequent paper, we are seeking an answer to our particular research question, that is, whether the systemic response against an inflammatory condition in the periodontium is related to the serum concentrations of ApoB and ApoA1. So far, the mechanisms or chemical structures that are responsible for the potential synergism or antagonism are not known, but this study supports the conception that ApoB or related factors play a role in determining a systemic response against the inflammatory condition of the periodontium.

Author Contributions

A.H., A.L.S. and P.Y. developed the concept for the study. A.L.S. conducted the statistical analyses. A.H., T.S., A.L.S., A.J. and P.Y. examined the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors participated in finalising the manuscript and have approved the final version.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of the Health 2000 Survey, organised by the National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) (http://www.terveys2000.fi), and partly funded by the Finnish Dental Society Apollonia and the Finnish Dental Association. The personal financing received from the Finnish Dental Society Apollonia and Finnish Association of Women Dentists is acknowledged by Anniina Haro. Open access publishing facilitated by Ita-Suomen yliopisto, as part of the Wiley - FinELib agreement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Description of the Formation of the Study Population

Diabetes was determined based on information obtained from the health examination and the health interview, and all those who had been diagnosed with diabetes by a physician or had some indication of the disease were excluded. The indications of diabetes included the following: fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or more, or a normal fasting blood glucose but blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L or more in the glucose tolerance test. Rheumatoid arthritis was determined based on the question: ‘Do you have rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed by a physician’, with the answer options being yes/no.

Description of the Measurement of Explanatory Variables

Five calibrated dentists carried out periodontal pocket measurements using a mouth mirror, head-lamp, and a WHO periodontal probe. Measurements were made at four predetermined sites per tooth (distobuccal, mid-buccal, mesio-oral, mid-oral) of each tooth except the third molars and radices. In the Health 2000 Survey, only the probing pocket depth (PPD) of the deepest pocket of each tooth was recorded as follows: no deepened periodontal pockets, periodontal pocket of PPD 4–5 mm and periodontal pocket of PPD ≥ 6 mm. For the statistical analyses, the number of teeth with periodontal pockets of PPD 4–5 mm or PPD ≥ 6 mm were combined to form the explanatory variable, namely the number of teeth with deepened (≥ 4 mm) periodontal pockets. This was categorized as follows: 0, 1–3, 4–6, 7–11 and ≥ 12 or more teeth. The second explanatory variable, the number of teeth with deep (≥ 6 mm) periodontal pockets, was categorized into four categories: 0, 1–3, 4–6 and ≥ 7 or more. Both explanatory variables were also used as continuous variables.

In the Health 2000 Survey, the concordance and reproducibility of periodontal pocket depth measurements were assessed by means of parallel measurements between the field examiners and the reference examiner (n = 269) and by means of intra-examiner repeat measurements (n = 111). Parallel measurements produced kappa value 0.41 (77% agreement), and the repeat measurements kappa value 0.83 (Vehkalahti et al. 2004, 2008).

Description of the Measurement of Other Variables

The educational level of the participants was categorized into three groups: basic education included those whose educational level was below upper secondary education, intermediate education included participants who had completed upper secondary education, and higher education included those who had graduated from university or university of applied sciences. Information about education was obtained in the home interview. Body weight was measured by means of using BMI, which is a measure of body weight in relation to height (kg/m2). Where information on height and weight was not available from in the clinical health examinations, information from a questionnaire was used.

The serum ApoB and ApoA1 concentrations were measured using immunoturbidimetry. For the stratified analyses, two strata were formed for ApoA1 and ApoB using medians as cut-offs: 1.12 g/L for ApoB and 1.55 g/L for ApoA1. Serum triglycerides were analyzed enzymatically (Olympus System Reagent, Olympus Life Science Research Europa GmbH, Munich, Germany). Serum LDL-C and HDL-C values were measured using direct methods based on immunocomplex separation followed by enzymatic cholesterol determination (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). These analyses were performed on an Olympus AU400 clinical chemistry autoanalyzer (Olympus Diagnostica GmbH, Hamburg, Germany).

Lipid-lowering medication was categorized as yes versus no. Information about the use of lipid-lowering medication was collected in the home interview. Information about physical activity was obtained from a questionnaire based on both Gothenburg's scale (Craig et al. 2003) and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire scale (Wilhelmsen et al. 1972), which measure the amount of leisure time activity, housework, walking and sitting. Physical activity was classified into three groups as follows: sufficient, intermediate and sedentary. Smoking habits/history were categorized as follows: non-smokers, those who smoked occasionally, and those who smoked daily. Information about smoking was obtained from the home interview.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.